Abstract

The κ-opioid receptor (KOR) is thought to play an important therapeutic role in a wide range of neuropsychiatric and substance abuse disorders, including alcohol dependence. LY2456302 is a recently developed KOR antagonist with high affinity and selectivity and showed efficacy in the suppression of ethanol consumption in rats. This study investigated brain penetration and KOR target engagement after single oral doses (0.5–25 mg) of LY2456302 in 13 healthy human subjects. Three positron emission tomography scans with the KOR antagonist radiotracer 11C-LY2795050 were conducted at baseline, 2.5 hours postdose, and 24 hours postdose. LY2456302 was well tolerated in all subjects without serious adverse events. Distribution volume was estimated using the multilinear analysis 1 method for each scan. Receptor occupancy (RO) was derived from a graphical occupancy plot and related to LY2456302 plasma concentration to determine maximum occupancy (rmax) and IC50. LY2456302 dose dependently blocked the binding of 11C-LY2795050 and nearly saturated the receptors at 10 mg, 2.5 hours postdose. Thus, a dose of 10 mg of LY2456302 appears well suited for further clinical testing. Based on the pharmacokinetic (PK)-RO model, the rmax and IC50 of LY2456302 were estimated as 93% and 0.58 ng/ml to 0.65 ng/ml, respectively. Assuming that rmax is 100%, IC50 was estimated as 0.83 ng/ml.

Introduction

Opioids are a family of peptides that produce their effects via G-protein–coupled receptors of at least three subtypes: μ (MOR), δ (DOR), and κ (KOR). There is a substantial body of evidence for KOR as a therapeutic target in a diverse set of neuropsychiatric and substance abuse disorders. For example, in alcohol dependence, an increasing number of reports have demonstrated efficacy of κ antagonists. A study by Walker and Koob (2008) found that the selective κ antagonist norbinaltorphimine selectively reduced ethanol intake in ethanol-dependent rats, suggesting that KOR antagonism could be a viable mechanism for the treatment of patients with a history of alcohol dependence. Additionally, the selective κ antagonist JDTic [(3R)-7-hydroxy-N-[(2S)-1-[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl]methyl]-2-methylpropyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinoline-carboxamide] decreased ethanol-seeking and relapse drinking in alcohol-preferring rats, but not maintenance responding (Deehan et al., 2012).

LY24563021 is a high-affinity, selective KOR antagonist that is being developed for the treatment of alcohol dependence. It has demonstrated at least a 30-fold functional selectivity over MOR and DOR as determined by in vitro opioid receptor binding experiments and in vivo receptor occupancy (RO) and pharmacology assays (Rorick-Kehn et al., 2014). In alcohol-preferring rats with a chronic ethanol drinking history, LY2456302 potently reduced ethanol self-administration (Rorick-Kehn et al., 2014). In addition, LY2456302 produced an antidepressant-like signal in a dose-dependent manner in the mouse forced swim test and appeared to have synergistic effects when administered with a sub-active dose of imipramine. Taken together, these data suggest that LY2456302 may hold potential in the treatment of ethanol-dependent patients with comorbid symptoms of depression.

The primary aim of this study was to demonstrate brain penetration and KOR target engagement after single oral doses of LY2456302 in healthy human subjects. KOR occupancy was assessed using the KOR specific antagonist radiotracer 11C-LY2795050 (Zheng et al., 2013; Naganawa et al., 2014, 2015) and positron emission tomography (PET) across a range of doses (0.5–25 mg) that have been demonstrated to be safe and well tolerated in a previous study (Lowe et al., 2014). We measured RO at multiple doses and postdosing times, and characterized the relationship between LY2456302 plasma concentrations and KOR occupancy.

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects.

Thirteen healthy male subjects (22–49 years of age, 88 ± 13 kg of weight) were enrolled. The study was approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee and the Yale-New Haven Hospital Radiation Safety Committee and in accordance with federal guidelines and regulations of the United States for the protection of human research subjects contained in Title 45 Part 46 of the Code of Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46). All subjects signed a written informed consent. As part of the subject evaluation, magnetic resonance images (MRIs) were acquired from each subject to eliminate those with anatomic abnormalities and for PET image registration. The MRI acquisition sequence was a three-dimensional MPRAGE MR pulse sequence (TE = 3.3 ms, flip angle 17 degrees, TI = 1100 ms, TR = 2500 ms) on a 3T whole-body scanner (Trio; Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) with a circularly polarized head coil. The dimension and pixel size of MRIs were 256 × 256 × 176 and 0.98 × 0.98 × 1.0 mm3, respectively.

Drug Synthesis and Supply.

LY2456302 was synthesized as previously reported (Mitch et al., 2011).

Radiotracer Synthesis.

11C-LY2795050 was synthesized as previously described (Zheng et al., 2013).

Study Design.

This was a single-dose PET imaging study to measure RO, PK, and a relationship between LY2456302 plasma concentrations and RO. PET imaging scans were conducted after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours.

A range of LY2456302 doses, which was demonstrated to be safe and well tolerated, was evaluated in this study: 0.5 mg (n = 2), 2 mg (n = 4), 4 mg (n = 2), 10 mg (n = 3), and 25 mg (n = 1). LY2456302 capsules were administered orally and subjects were required to continue fasting for at least 4 hours after dosing. A model-based adaptive design approach was used to determine the dose levels, and the sample size after RO and plasma drug levels were obtained after the initial dose level (2 mg), which ensured the best use of the subjects to characterize the relationship between KOR occupancy and LY2456302 dosing and exposure.

Each subject underwent three PET scans (a baseline and two postdose scans) with 11C-LY2795050. First, a baseline scan was performed, after a single oral administration of LY2456302. Two postdose PET scans were conducted at 2.5 and 24 hours after LY2456302 administration. Timing of the post-dose PET scans was selected based on human PK: maximum observed drug concentration in the plasma at 2.5 hours postdose (tmax) and trough level at 23–25 hours postdose. The baseline and 2.5 hours postdose PET scans were conducted on the same day, and the 24-hour postdose scan was performed on the following day.

Safety was assessed by physical examinations, collection of vital signs, electrocardiograms, standard laboratory tests, and the recording of adverse events (AEs).

Plasma Metabolite Analysis and Arterial Input Function Measurement.

A full description of the arterial input function measurement can be found in a previous publication (Naganawa et al., 2014). Briefly, on each PET scan day, an indwelling arterial catheter was placed for blood sampling. An automated sampling system (PBS-101; Veenstra Instruments, Joure, The Netherlands) was used to measure the radioactivity in the whole blood plasma continuously during the first 7 minutes. Subsequently, arterial samples (2–10 ml) were collected manually for blood and metabolite analysis. Arterial plasma samples at 5, 15, 30, 60, and 90 minutes were used for analysis of the unmetabolized fraction of radiotracer using a modified column-switching high-performance liquid chromatography method (Hilton et al., 2000). The unmetabolized parent fraction was fitted to a sum of exponentials.

Arterial blood sampling was not available for the 24-hour postdose scan in three subjects and for the baseline and 2.5 hours postdose scans in one subject. The metabolite-corrected input function collected on the other day (baseline scan for three subjects or the 24-hour postdose scan for one subject) was scaled by the ratio of the injected doses to derive the input function.

Plasma Drug Concentration Measurement.

Up to nine venous blood samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 2.5, 4, 6, 8, 12, 22.5, and 24 hours after drug administration for determination of plasma concentration of LY2456302 by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), with the lower limit of quantification at 0.20 ng/mL, as described previously (Lowe et al., 2014).

Image Acquisition.

All dynamic PET scans were acquired for 90 minutes on high-resolution research tomography (HRRT) (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN), which acquires 207 slices (1.2-mm slice separation) with a reconstructed image resolution of approximately 3 mm. Postdose scans could not be completed for one subject and were therefore excluded from the PK-RO analysis. A 6-minute transmission scan was conducted before radiotracer injection for attenuation correction. Each scan was acquired in list mode after intravenous administration of 11C-LY2795050 (mean ± S.D.: 388 ± 167 MBq, n = 37) over 1 minute by an automatic pump (Harvard PHD 22/2000; Harvard Apparatus Holliston, MA). Dynamic scan data were reconstructed in 27 frames (6 × 0.5, 3 × 1, 2 × 2, and 16 × 5 minutes) with corrections for attenuation, normalization, scatter, randoms, and deadtime using the MOLAR algorithm (Carson et al., 2003; Jin et al., 2013). Motion correction was included in the reconstruction algorithm based on measurements with the Polaris Vicra sensor (NDI Systems, Waterloo, Canada) with reflectors mounted on a swim cap worn by the subject.

Image Registration and Definition of Regions of Interest.

Regions of interest (ROI) were taken from the Automated Anatomic Labeling (AAL) for SPM2 (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) in Montreal Neurologic Institute (Montreal, QC, Canada) space (Holmes et al., 1998). For each subject, the dynamic PET images were coregistered to the early summed PET images (0–10 minutes postinjection) using a six-parameter mutual information algorithm (FLIRT, FSL) (Viola and Wells, 1997) to eliminate any residual motion. The summed PET image was then registered to the subject’s T1-weighted 3T MRI (six-parameter rigid registration), which was subsequently registered to the AAL template using a nonlinear transformation (Bioimage Suite) (Papademetris et al., 2005). Using the combined transformations from template-to-PET space, regional time-activity curves (TACs) were generated for 13 ROIs: amygdala, caudate, cerebellum, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, frontal cortex, globus pallidus, hippocampus, insula, occipital cortex, putamen, temporal cortex, and thalamus.

Modeling and RO Calculation.

Based on our previous study (Naganawa et al., 2014), the multilinear analysis-1 method (Ichise et al., 2003) with t* = 20 minutes was applied to the regional TACs using the arterial plasma TAC as input function to calculate distribution volume (VT) (Innis et al., 2007). All modeling was performed with inhouse programs written with IDL 8.0 (ITT Visual Information Solutions, Boulder, CO). RO for each postdose scan was calculated using an occupancy plot, shown in eq. 1 (Cunningham et al., 2010):

| (1) |

where VND is the nondisplaceable distribution volume, and VT is the regional distribution volume obtained at baseline or postdrug administration.

PK-RO Analysis.

The PK parameter estimates for LY2456302 were calculated by standard noncompartmental methods to characterize basic PK properties. Primary parameters were maximum observed drug concentration (Cmax) and area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) of LY2456302. Other noncompartmental parameters, such as apparent clearance and apparent volume of distribution, were also calculated. Individual and population PK parameter estimates for LY2456302 were calculated using nonlinear mixed effect (NLME) modeling for PK-RO analysis.

The PK-RO relationship between LY2456302 plasma concentration and KOR occupancy was evaluated using the conventional sigmoidal rmax model, shown in eq. 2:

|

(2) |

where CP is the LY2456302 plasma concentration, and IC50 is the LY2456302 plasma concentration required to produce 50% of the maximum RO (rmax). Two approaches were used to analyze the data. First, a nonlinear least squares (NLLS) analysis was employed to directly estimate the parameters from all the pooled data (i.e., pairs of RO and CP from all scans). In this analysis, either two parameters (IC50, rmax) or one parameter (IC50, rmax=100%) were estimated. This NLLS analysis ignores intersubject variability for each parameter. Second, a NLME model was used, which included the intersubject variability of IC50. The confidence intervals of all parameter estimates were calculated.

Results

Injection Parameters.

Injection parameters of the radiotracer are listed in Table 1. Injected mass was carefully controlled and so was not significantly different between baseline and postdose scans. As a result of differences in specific activity (specific activity of the radiotracer for the 2.5-hour postdose scans was significantly higher than that for the baseline scans, P = 0.048), the injected activity dose of the postdose scans was significantly higher than that of the baseline scans (2.5 hours postdose: P = 0.002, 24 hours postdose: P = 0.045). Since kinetic modeling was applied to these data, differences in injected dose had no effect on the results.

TABLE 1.

11C-LY2795050 injection parameters

| Parameter | Baseline (n = 13) | 2.5 h post-dose (n = 12) | 24 h post-dose (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injected dose (MBq) | 255 ± 163 | 399 ± 155 | 366 ± 160 |

| Injected mass (μg) | 8.15 ± 2.62 | 9.25 ± 0.94 | 9.06 ± 1.32 |

| Specific activity at time of injection (MBq/nmol) | 13 ± 6 | 18 ± 6 | 17 ± 8 |

Data are mean ± S.D.

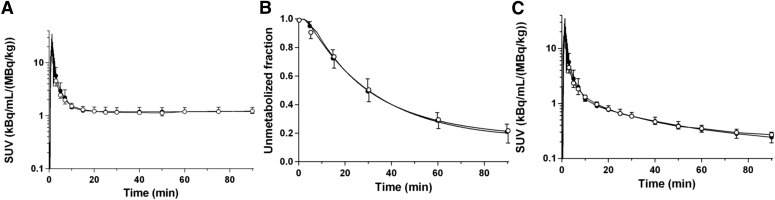

Metabolite Analysis and Arterial Input Function.

Total plasma activity and parent fraction in the baseline scans were similar to those from the 2.5 hours postdose scans with 10 mg of LY2456302 (Fig. 1, A and B). The metabolite-corrected plasma activity is shown in Fig. 1C.

Fig. 1.

Mean ± S.D. of total plasma activity (A), unmetabolized fraction in the plasma (B), and metabolite-corrected plasma activity (C) after injection of 11C-LY2795050 in the baseline scans (closed circles, n = 12) and 2.5-hour postdose scans after oral dose of 10 mg LY2456302 (open circles, n = 3).

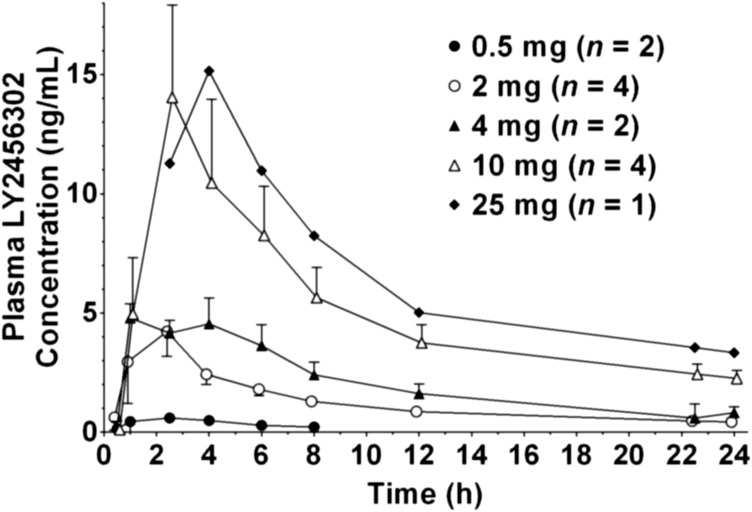

Pharmacokinetics.

Mean plasma LY2456302 concentration-time profiles after single oral doses are shown in Fig. 2. Table 2 provides summary statistics of LY2456302 PK parameters at each dose. LY2456302 plasma concentrations were not collected beyond 24 hours postdose; therefore, PK parameters based on the terminal elimination phase were not calculated. Peak LY2456302 plasma concentrations were typically observed approximately 2.5 hours postdose. There was no clear nonlinearity in dose-dependency apparent in Cmax or AUC (from time zero to the last time point: 0–tlast). Dose-normalized Cmax and AUC (0—tlast) had intersubject variability of 62% and 48%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

LY2456302 mean plasma concentration-time profiles after single doses of 0.5, 2, 4, 10, and 25 mg of LY2456302. Error bars indicate S.E.M. Samples after 8 hours for 0.5 mg and before 2.5 hours for 25 mg were lower than the limit of quantification (<0.20 ng/ml).

TABLE 2.

PK parameters after single doses of LY2456302

|

aGeometric Mean (Geometric %COV) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mg (n = 2) | 2 mg (n = 4) | 4 mg (n = 2) | 10 mg (n = 4) | 25 mg (n = 1) | |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 0.53–0.90 | 4.20 (71%) | 4.21–5.63 | 12.6 (61%) | 15.2 |

| btmax (h) | 1.00–2.55 | 2.50 (1.00–4.00) | 1.00–4.00 | 2.50 (2.50–4.00) | 4.07 |

| AUC (0–tlast) (ng ∣ h / ml) | 2.42–3.66 | 28.4 (45%) | 39.5–62.1 | 112 (45%) | 154 |

The range for all parameters is reported where n = 2. Individual parameter is reported where n = 1.

Median (range).

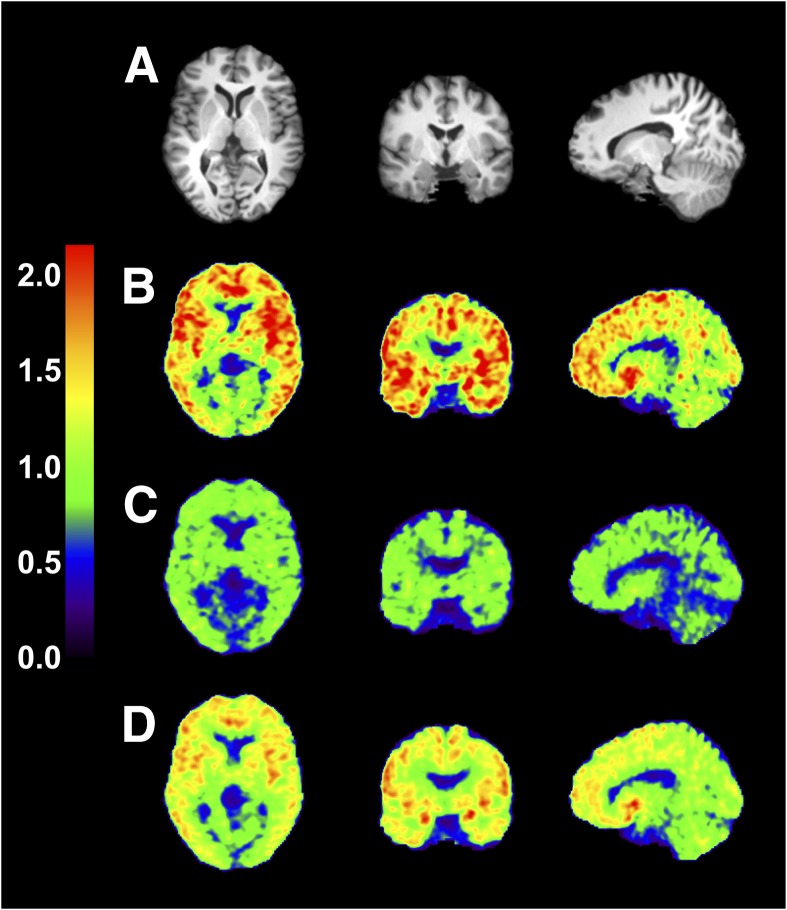

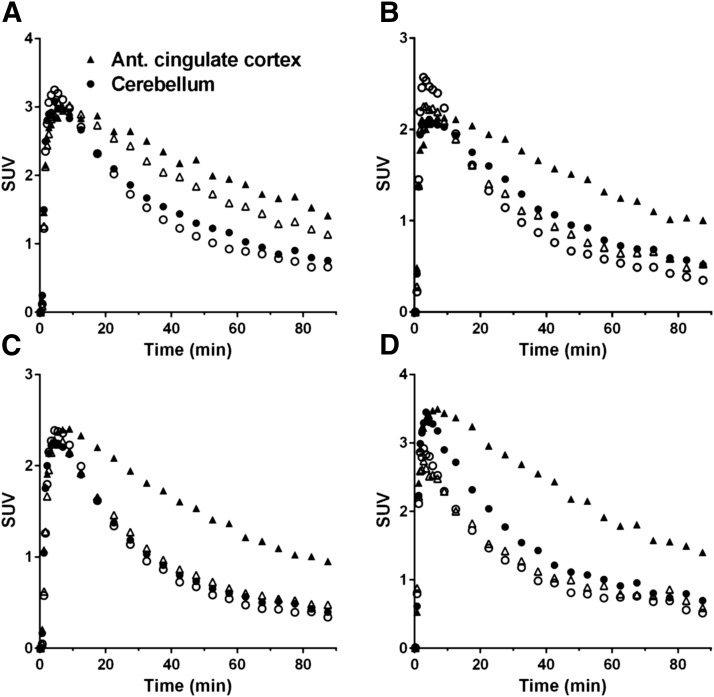

Receptor Occupancy.

Figure 3 shows SUV images in the baseline scan and two postdose scans after oral dose of 2 mg of LY2456302. SUV was globally reduced at 2.5 hours postdose and partially recovered at 24 hours postdose. Figure 4 shows regional TACs in the baseline scan and 2.5 hours post-dose scans with various doses. Regional VT values and their coefficients of variation using multilinear analysis-1 are listed in Table 3. The VT values decreased in a dose-dependent manner. In the postdose scans VT values were reduced in all regions, indicating, as shown previously, that there are no reference regions devoid of KOR. Representative occupancy plots are shown in Fig. 5, and RO and VND values are summarized in Table 4.

Fig. 3.

Images from a typical subject before and after oral dose of 2 mg of LY2456302. MR images (A) and coregistered PET images summed from 30 to 90 minutes after injection of 11C-LY2795050 in the baseline scan (B), and 2.5 hours (C) and 24 hours (D) postdose scans. Activity is expressed as SUV.

Fig. 4.

Regional time-activity curves in two regions in the baseline scans (closed symbols) and 2.5 hours postdose scans (open symbols), with LY2456302 doses of 0.5 mg (A), 2 mg (B), 4 mg (C), and 10 mg (D).

TABLE 3.

Volume of distribution (VT) values from multilinear analysis-1

| Region | VT (ml/cm3) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aBaseline (%COV) |

bBlocking with LY2456302 (%COV) |

||||||||||

| 2.5 h Postdose |

24 h Postdose |

||||||||||

| 0.5 mg | 2 mg | 4 mg | 10 mg | 25 mg | 0.5 mg | 2 mg | 4 mg | 10 mg | 25 mg | ||

| Amygdala | 3.46 (10%) | 2.73 (16%) | 1.89 (14%) | 1.79 (7%) | 1.43 (22%) | 1.51 | 3.02 (7%) | 2.42 (23%) | 2.52 (4%) | 1.97 (7%) | 1.63 |

| Insula | 2.99 (9%) | 2.35 (17%) | 1.79 (15%) | 1.69 (9%) | 1.51 (19%) | 1.53 | 2.81 (18%) | 2.36 (18%) | 2.22 (0%) | 1.88 (6%) | 1.61 |

| Ant. cingulate cortex | 3.00 (8%) | 2.37 (14%) | 1.73 (17%) | 1.72 (10%) | 1.51 (18%) | 1.56 | 2.73 (12%) | 2.30 (20%) | 2.20 (1%) | 1.89 (7%) | 1.65 |

| Globus pallidus | 2.70 (13%) | 2.27 (15%) | 1.89 (17%) | 1.88 (8%) | 1.62 (21%) | 1.79 | 2.56 (13%) | 2.29 (22%) | 2.16 (0%) | 1.94 (3%) | 1.78 |

| Putamen | 2.65 (9%) | 2.13 (16%) | 1.82 (13%) | 1.81 (8%) | 1.67 (19%) | 1.67 | 2.47 (16%) | 2.21 (15%) | 2.10 (1%) | 1.91 (3%) | 1.73 |

| Temporal cortex | 2.42 (7%) | 1.98 (15%) | 1.64 (13%) | 1.65 (10%) | 1.53 (18%) | 1.52 | 2.33 (15%) | 2.02 (14%) | 1.98 (1%) | 1.74 (5%) | 1.52 |

| Frontal cortex | 2.39 (8%) | 2.01 (16%) | 1.57 (13%) | 1.61 (11%) | 1.48 (17%) | 1.52 | 2.32 (16%) | 1.94 (17%) | 1.94 (4%) | 1.70 (6%) | 1.49 |

| Occipital cortex | 2.30 (8%) | 1.90 (12%) | 1.67 (16%) | 1.76 (9%) | 1.61 (13%) | 1.67 | 2.18 (9%) | 1.99 (13%) | 1.99 (3%) | 1.80 (4%) | 1.67 |

| Hippocampus | 2.07 (9%) | 1.81 (22%) | 1.47 (13%) | 1.49 (6%) | 1.39 (21%) | 1.47 | 2.05 (30%) | 1.63 (18%) | 1.69 (0%) | 1.61 (7%) | 1.50 |

| Caudate | 1.90 (11%) | 1.43 (9%) | 1.33 (12%) | 1.39 (11%) | 1.29 (28%) | 1.36 | 1.73 (11%) | 1.57 (15%) | 1.55 (1%) | 1.49 (16%) | 1.40 |

| Post. cingulate cortex | 1.87 (11%) | 1.59 (0%) | 1.42 (14%) | 1.41 (7%) | 1.34 (26%) | 1.43 | 1.84 (1%) | 1.59 (27%) | 1.65 (8%) | 1.50 (8%) | 1.32 |

| Thalamus | 1.88 (7%) | 1.75 (12%) | 1.68 (9%) | 1.70 (8%) | 1.60 (22%) | 1.75 | 1.87 (17%) | 1.71 (14%) | 1.76 (3%) | 1.75 (2%) | 1.72 |

| Cerebellum | 1.86 (18%) | 1.53 (18%) | 1.44 (15%) | 1.57 (14%) | 1.43 (14%) | 1.52 | 1.69 (23%) | 1.60 (14%) | 1.75 (22%) | 1.60 (5%) | 1.49 |

Baseline scans with 11C-LY2795050 (n = 12).

11C-LY2795050 PET scans after oral administration of LY2456302 (0.5 mg, n = 2; 2 mg, n = 4; 4 mg, n = 2; 10 mg, n = 3; 25 mg, n = 1).

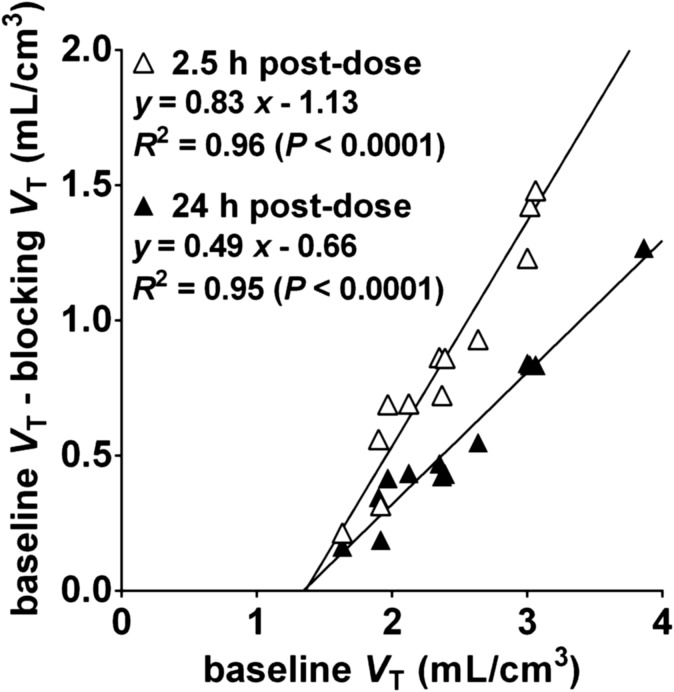

Fig. 5.

Representative occupancy plots from the 2.5-hour and 24-hour postdose scans after oral dose of 4 mg LY2456302. Fitted occupancy values were 83% and 49%, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Receptor occupancy and nondisplaceable distribution volume (VND) estimates

| LY2456302 Dose | 2.5 h Postdose |

24 h Postdose |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupancy | VND | Occupancy | VND | |

| % | ml/cm3 | % | ml/cm3 | |

| 0.5 mg (n = 2) | 35 ± 4 | 1.23 ± 0.06 | 19 ± 3 | 1.92 ± 0.21 |

| 2 mg (n = 4) | 71 ± 10 | 1.32 ± 0.19 | 43 ± 14 | 1.41 ± 0.25 |

| 4 mg (n = 2) | 79 ± 6 | 1.43 ± 0.10 | 48 ± 1 | 1.37 ± 0.03 |

| 10 mg (n = 3) | 94 ± 0.5 | 1.43 ± 0.10 | 72 ± 4 | 1.51 ± 0.10 |

| 25 mg (n = 1) | 93 | 1.50 | 82 | 1.40 |

Data are mean ± S.D. Individual parameters are reported where n = 1.

Single oral doses of LY2456302 (0.5–25 mg) blocked KOR in the brain in a dose-dependent manner. At 2.5 hours postdose (peak plasma concentration), RO from occupancy plots ranged from 35 ± 4% (n = 2) for the 0.5-mg dose level to 94 ± 0.5% (n = 3) for the 10-mg dose level. Doses of 10 mg and 25 mg LY2456302 nearly saturated the KOR (RO of 93 ± 0.7%, n = 4) at peak plasma concentration with VND of 1.45 ± 0.25 ml/cm3 (n = 4). Target engagement was observed for at least 24 hours after dosing. RO at 24 hours postdose ranged from 19 ± 3% at 0.5 mg (n = 2) to 82% (n = 1) at 25 mg of LY2456302.

PK-RO Analysis.

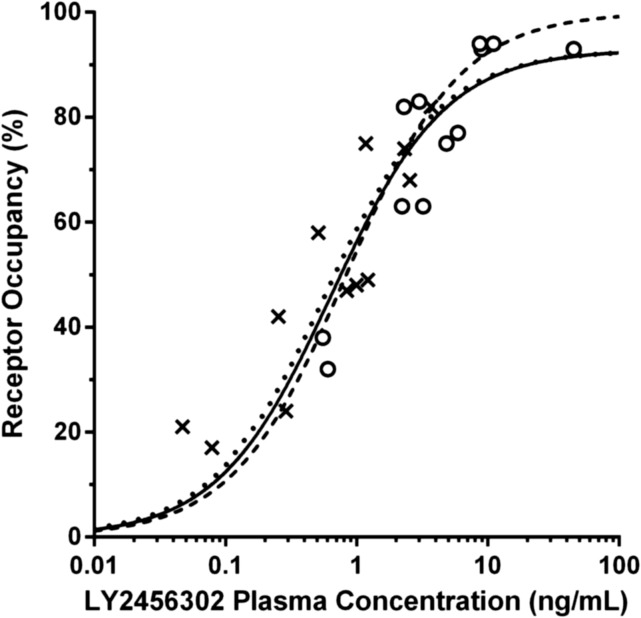

Table 5 lists the population parameter estimates from the PK model. The PK parameters were estimated with good precision, with relative standard errors (rSE) of <30%. The relationship between KOR occupancy and LY2456302 plasma concentration is shown in Fig. 6, and the data were consistent with occupancy at a single site.

TABLE 5.

Population PK parameter estimates

| PK Parameter | Population Estimate | Intersubject Variability |

|---|---|---|

| % rSE | % rSE | |

| Ka (h−1) | 9.48 (9.35) | 29.5% (34.3) |

| CL/F (liters/h) | 55.2 (12.9) | 46.4% (21.7) |

| Vc/F (liters) | 561 (16.5) | 60.3% (33.9) |

| Q/F (liters/h) | 59.3 (17.4) | 42.8% (40.0) |

| Vp/F (liters) | 705 (27.4) | — |

| Residual error | ||

| Additive (ng/ml) | 0.09 (31.8) | |

| Proportional | 12.8% (21.6) |

CL/F, apparent total body clearance of drug calculated after extravascular administration; Ka, transit absorption rate constant; Q/F, apparent intercompartmental clearance; rSE, relative standard error; Vc/F, apparent volume of distribution of the central component; Vp/F, apparent volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between predicted LY2456302 plasma concentration and KOR occupancy. Three fits are shown: two-parameter (rmax and IC50) NLME model (dotted curve), two-parameter NLLS model (solid curve), and one-parameter (IC50, rmax = 100%) NLLS model (break curve). Plasma concentrations at the time of each postdose scan were calculated from a PK model applied to the observed PK data. Occupancies at 2.5 hours and 24 hours postdose are shown in circles and crosses, respectively.

Table 6 lists the PK-RO model parameters. The 95% confidence interval for the PK-RO model parameters resulting from the sensitivity analysis are also provided in Table 6. These were fairly narrow, suggesting that the model parameters were well estimated. The estimate of IC50 using the NLLS model with two parameters was similar to the NLME estimate (∼0.6 ng/ml). The one-parameter version of the NLLS model produced a slightly higher estimate (0.83 ng/ml). Using the F test, the two-parameter NLLS model was not statistically better than the one-parameter model (P = 0.17). For the NLME model, the interindividual variability in IC50 was estimated at 29%, albeit with a large rSE of 150%. The rmax estimate was 93% for both NLME and two-parameter NLLS models, which indicates near complete saturation of KOR in the brain at high concentrations of LY2456302.

TABLE 6.

PK-RO Parameter Estimates

| Parameter | Mean Estimates (%rSE) | Intersubject Variability (%rSE) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| NLLS model (1-parameter) | ||||

| IC50 (ng/ml) | 0.83 (12) | 0.63 | 1.03 | |

| NLLS model (2-parameter) | ||||

| rmax (%) | 92.9 (4.9) | 83.4 | 102 | |

| IC50 (ng/ml) | 0.65 (20) | 0.37 | 0.92 | |

| Nonlinear mixed effect (NLME) | ||||

| rmax (%) | 92.8 (4.7) | 85.5 | 101 | |

| IC50 (ng/ml) | 0.58 (25) | 29.4% (150) | 0.38 | 0.85 |

rmax, maximum receptor occupancy; %rSE, relative standard error.

In Fig. 6, there was a suggestion of hysteresis; that is, there was some difference between the PK-RO relationship at tmax and at 24 hours. To evaluate this effect, the one-parameter NLLS model was applied separately to the tmax data and the 24-hour data, and the F test was used to evaluate the potential improvement in fit. The IC50 estimates were 1.05 ± 0.14 ng/ml at tmax, and 0.70 ± 0.12 ng/ml at 24 hours compared with 0.83 ± 0.10 ng/ml using all the data; however, the improvement in fit was not significant (P = 0.09).

Safety and Tolerability.

No serious AEs occurred during the study, and there were no clinically significant alterations in laboratory values or electrocardiograms. No subject discontinued the study because of an AE. Of the reported AEs, all were mild or moderate and none were considered by the investigator to be related to the study drug.

Discussion

Using the KOR antagonist tracer 11C-LY2795050 and PET, this study investigated the receptor occupancy of LY2456302 after single oral administration at various dose levels and the PK-RO relationship. Brain KORs were almost saturated at 2.5 hours postdose with doses of 10 mg or more. Sustained and substantial target engagement was observed for at least 24 hours.

The relationship between LY2456302 plasma concentration and KOR occupancy was analyzed with a direct PK-RO model. Depending on the model, the estimate of IC50 was 0.6∼0.8 ng/ml with saturation of the receptor evident at high doses. Primarily, LY2456302 RO appeared to decline in parallel with the plasma concentration; however, comparison of RO values at tmax and 24 hours showed a small shift in the PK-RO curve (Fig. 6), suggesting the presence of a moderate time lag in equilibration with the central nervous system compartment. If so, the KOR occupancy at tmax would be less than that at later times, so that the tmax RO values tend to be below the overall curve of best fit, whereas the 24 hour points tend to be above the curve of best fit. This effect is somewhat visible on the steeper portion of the PK-RO curve. An initial analysis found a trend (P = 0.09) toward different IC50 values at tmax and 24 hours. For further evaluation, indirect effect models (Abanades et al., 2011; Salinas et al., 2013) could be applied; these models characterize hysteresis in the PK-RO curve by modeling the blood-brain exchange and binding kinetics of the drug.

Given that VT values decreased in all regions by LY2456302, KOR is expressed ubiquitously in the brain. Hence, it is not possible to determine a reference region devoid of KOR. Thus, the occupancy plot was used to estimate RO and VND in the absence of a reference region. The estimated VND value at high doses (10 and 25 mg, RO = 93 ± 0.7%) of LY2456302 was 1.45 ml/cm3 (range: 1.10–1.69 ml/cm3). This value was consistent with the VT estimates from a previous study when 150 mg of naltrexone was used to fully block KOR in the human brain (RO = 93 ± 6%, VND = 1.61 ml/cm3, range: 1.13–2.06 ml/cm3) (Naganawa et al., 2014).

Here we evaluated the KOR binding of LY2456302 with the antagonist radiotracer 11C-LY2795050. This tracer was shown to be selective for KOR in vivo (Kim et al., 2013), with a small amount of binding attributable to MOR. It was previously shown that LY2456302 had a 30-fold selectivity over MOR and DOR (Rorick-Kehn et al., 2014). To further assess any MOR activity, LY2456302 (4–60 mg) was orally administered to healthy humans to assess the effect on fentanyl-induced miosis in a previous pupillometry study (Rorick-Kehn et al., 2015). Doses of 25–60 mg yielded minimal to moderate MOR blockade, with no effect seen at 4 and 10 mg. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that LY2456302 remains functionally selective for KOR at lower doses (4–10 mg) but produces modest MOR antagonism at higher doses. In the present study, the maximum dose of 25 mg was selected to minimize MOR effects.

In conclusion, LY2456302, when administered as single, oral doses of 0.5 mg up to 25 mg, penetrated the blood-brain barrier and blocked KOR in the brain in a dose-related manner. Almost complete saturation of KORs was observed at doses of 10 mg or more at 2.5 hours postdose. Substantial and sustained target engagement was observed for at least 24 hours postdose. A sigmoidal rmax PK-RO model, which assumes a direct relationship between RO and the plasma concentration of LY2456302, was a suitable model. According to this model, the rmax of LY2456302 was 93% (i.e., complete saturation of the target) and the plasma IC50 was estimated at ∼0.6 ng/ml. Given that a single oral dose of 10 mg LY2456302 almost completely saturated KOR at 2.5 hours postdose, and that the lower bound of the observed KOR occupancy at 24 hours postdose exceeded 60%, a dose of 10 mg of LY2456302 appears very well suited for further clinical testing.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the excellent technical assistance of the staff at the Yale University PET Center and gratefully acknowledge the review provided by Cerecor Inc.

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- AUC

area under the concentration versus time curve

- DOR

δ-opioid receptor

- LY2795050

(S)-3-chloro-4-(4-((2-(pyridin-3-yl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)phenoxy)benzamide

- LY2456302

(S)-4-(4-((2-(3,5-dimethylphenyl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)phenoxy)-3-fluorobenzamide

- Cmax

maximum observed drug concentration

- KOR

κ-opioid receptor

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NLLS

nonlinear least squares

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- rmax

maximum occupancy

- RO

receptor occupancy

- ROI

region of interest

- TAC

time-activity curve

- tmax

time of maximum drug level in plasma

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Henry, Witcher, Neumeister, Ranganathan, Huang, Tauscher, Carson.

Conducted experiments: Zheng, Nabulsi, Lin, Ropchan, Ranganathan.

Performed data analysis: Naganawa, Dickinson, Vandenhende, Bell, Witcher.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Naganawa, Dickinson, Vandenhende, Nabulsi, Lin, Huang, Carson.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Eli Lilly and Company. This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant UL1 TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH.

Since the conduct of this study, Cerecor has acquired exclusive, worldwide rights from Eli Lily and Company to develop and commercialize LY2456302 (which has now been designated as CERC-501). For further information, see clinicaltrials.gov.

References

- Abanades S, van der Aart J, Barletta JA, Marzano C, Searle GE, Salinas CA, Ahmad JJ, Reiley RR, Pampols-Maso S, Zamuner S, et al. (2011) Prediction of repeat-dose occupancy from single-dose data: characterisation of the relationship between plasma pharmacokinetics and brain target occupancy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31:944–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RE, Barker WC, Liow JS, and Johnson CA(2003) Design of a motion-compensation OSEM list-mode algorithm for resolution-recovery reconstruction for the HRRT. IEEE 2003 Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record 5:3281–3285. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham VJ, Rabiner EA, Slifstein M, Laruelle M, Gunn RN. (2010) Measuring drug occupancy in the absence of a reference region: the Lassen plot re-visited. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30:46–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deehan GA, Jr, McKinzie DL, Carroll FI, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA. (2012) The long-lasting effects of JDTic, a kappa opioid receptor antagonist, on the expression of ethanol-seeking behavior and the relapse drinking of female alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 101:581–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton J, Yokoi F, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Szabo Z, Wong DF. (2000) Column-switching HPLC for the analysis of plasma in PET imaging studies. Nucl Med Biol 27:627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CJ, Hoge R, Collins L, Woods R, Toga AW, Evans AC. (1998) Enhancement of MR images using registration for signal averaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 22:324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, Takano A, Model K, Toyama H, Suhara T, Suzuki K, Innis RB, Carson RE. (2003) Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23:1096–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, Holden J, Houle S, Huang SC, Ichise M, et al. (2007) Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27:1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Mulnix T, Gallezot JD, Carson RE. (2013) Evaluation of motion correction methods in human brain PET imaging--a simulation study based on human motion data. Med Phys 40:102503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Zheng MQ, Nabulsi N, Labaree D, Ropchan J, Najafzadeh S, Carson RE, Huang Y, Morris ED. (2013) Determination of the in vivo selectivity of a new κ-opioid receptor antagonist PET tracer 11C-LY2795050 in the rhesus monkey. J Nucl Med 54:1668–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SL, Wong CJ, Witcher J, Gonzales CR, Dickinson GL, Bell RL, Rorick-Kehn L, Weller M, Stoltz RR, Royalty J, et al. (2014) Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic evaluation of single- and multiple-ascending doses of a novel kappa opioid receptor antagonist LY2456302 and drug interaction with ethanol in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 54:968–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitch CH, Quimby SJ, Diaz N, Pedregal C, de la Torre MG, Jimenez A, Shi Q, Canada EJ, Kahl SD, Statnick MA, et al. (2011) Discovery of aminobenzyloxyarylamides as κ opioid receptor selective antagonists: application to preclinical development of a κ opioid receptor antagonist receptor occupancy tracer. J Med Chem 54:8000–8012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naganawa M, Zheng MQ, Henry S, Nabulsi N, Lin SF, Ropchan J, Labaree D, Najafzadeh S, Kapinos M, Tauscher J, et al. (2015) Test-retest reproducibility of binding parameters in humans with 11C-LY2795050, an antagonist PET radiotracer for the κ opioid receptor. J Nucl Med 56:243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naganawa M, Zheng MQ, Nabulsi N, Tomasi G, Henry S, Lin SF, Ropchan J, Labaree D, Tauscher J, Neumeister A, et al. (2014) Kinetic modeling of (11)C-LY2795050, a novel antagonist radiotracer for PET imaging of the kappa opioid receptor in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34:1818–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papademetris X, Jackowski M, Rajeevan N, Constable RT, Staib LH. (2006) BioImage Suite: An integrated medical image analysis suite: an update. Insight J 2006:209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorick-Kehn LM, Witcher JW, Lowe SL, Gonzales CR, Weller MA, Bell RL, Hart JC, Need AB, McKinzie JH, Statnick MA, et al. (2015) Determining pharmacological selectivity of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist LY2456302 using pupillometry as a translational biomarker in rat and human. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorick-Kehn LM, Witkin JM, Statnick MA, Eberle EL, McKinzie JH, Kahl SD, Forster BM, Wong CJ, Li X, Crile RS, et al. (2014) LY2456302 is a novel, potent, orally-bioavailable small molecule kappa-selective antagonist with activity in animal models predictive of efficacy in mood and addictive disorders. Neuropharmacology 77:131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas C, Weinzimmer D, Searle G, Labaree D, Ropchan J, Huang Y, Rabiner EA, Carson RE, Gunn RN. (2013) Kinetic analysis of drug-target interactions with PET for characterization of pharmacological hysteresis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. (2002) Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15:273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola P, Wells WM., III (1997) Alignment by maximization of mutual information. Int J Comput Vis 24:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Walker BM, Koob GF. (2008) Pharmacological evidence for a motivational role of kappa-opioid systems in ethanol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:643–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng MQ, Nabulsi N, Kim SJ, Tomasi G, Lin SF, Mitch C, Quimby S, Barth V, Rash K, Masters J, et al. (2013) Synthesis and evaluation of 11C-LY2795050 as a κ-opioid receptor antagonist radiotracer for PET imaging. J Nucl Med 54:455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]