Abstract

Little research exists on the formation of professional identity in higher education health programs. Such programs may approach the teaching, learning, and assessment of professionalism based upon a suite of attitudes, values, and behaviors considered indicative of a practicing professional. During this transition, professional identity formation can be achieved through student engagement with authentic experiences and interaction with qualified professionals. This paper examines the shift toward identity formation as an essential element of professional education and considers its implications for pharmacy curriculum design.

Keywords: professional identity, pharmacy education, health professionals, professionalization

INTRODUCTION

In 2010, a Global Independent Commission into the Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century called for educational reforms to better prepare graduates working in health fields.1 The commission identified inequitable distribution of health care expertise, threats to health security, and increased demands on health workers as some of the challenges facing those working in health care. The commission also pointed out that graduates were poorly prepared for these challenges in the global health context.

The call for new reforms followed 2 previous calls, both aiming to transform health education. The first, inspired by the 1910 Flexner report, recommended that science knowledge form the basis of health education in a period that saw a dramatic reduction in mortality rates.1 The second call was characterized by the introduction of problem-based learning into medical curricula. An independent commission consisting of 20 academic and professional leaders from around the world concluded that health education programs were not preparing graduates to respond to demands of the health system and that a curriculum redesign for health education was urgently needed. In particular, they stated: “Professional education… must inculcate responsible professionalism, not only through explicit knowledge and skills, but also by promotion of an identity and adoption of the values, commitments, and disposition of the profession.”1 Moreover, in 2014, The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) alerted both practitioners and those in pharmacy education to challenging times ahead as the practice of pharmacy continued to become more complex and demanding.2

Approaches to professional education primarily focus on competence-based models, where the student is required to demonstrate attitudes, beliefs, and values pertinent to a particular profession.3,4 Recent research demonstrates that while creating a culture of professionalism and being explicit about professional expectations is important,5 more focus needs to be placed on the development of student professional identity.6 Course designers need to examine ways to achieve professional socialization of the student, where focus is placed on who the student is becoming.7 This identity formation will prepare them most effectively for the challenges which lie ahead.7 Exposure to the profession through access to role models and experiential learning serves to effectively acculturate aspiring professionals.5,8,9 Thus, this paper examines implications of the decline in professionalism for health education programs and highlights the challenge in defining professionalism among professional agencies. This paper also describes current approaches to professional education, namely increasing attention directed toward developing a professional identity as a mechanism for professionalization.

DECLINE IN SOCIAL VALUES

There are misgivings regarding the decline of professionalism and common civility in society at large.3,8,10,11 Examples of professional misconduct and occasions of fraud across disciplines highlight the issue of professionalism and the need to address these issues during university education.12,13 Undergraduate students are also perpetrators of unprofessional behaviors, fueled by lowering standards as educational institutions are pressured to placate students who feel entitled to special treatment.14 The need for instruction in professional conduct in health education was highlighted over a century ago. Abraham Flexner’s full vision for medical education in 1910 included not only technical and cognitive skills, but also core professional values such as compassion, service, and altruism.15 These characteristics lie at the heart of those working in the health professions such as medicine, nursing, and pharmacy. Aguilar and colleagues explained the importance of professionalism in these settings: “Health practitioners’ professionalism can impact patient care, health outcomes, therapeutic relationships, and the public’s perception and trust of a profession and its members.”3

Pharmaceutical care, a model focusing on patient wellbeing and optimal outcomes from medication usage, demands a new level of professionalism in its practitioners.8 Waterfield described pharmacists as having particular moral responsibilities as “gatekeepers to safe drug usage,” a critical element in human health and safety.16 Since mandatory student registration and reporting was introduced in 2010 by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA),17 the issue of student professionalism has become more entwined with and reflective of health professions educational programs.

DEFINING PROFESSIONALISM

The professionalism movement began more than 30 years ago when Arnold Relman, editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, expressed concern over a rise in business influence on physician practices. In response, others called for a return to core professional values, where the interests and well-being of patients were the central concerns.18 Knowing which characteristics define the professional is problematic, and, despite extensive efforts, agreed universal definition has yet to be achieved.3,19-23 The main driver towards the development of a definition for professionalism was initially led by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM).24 In 1995, the Board established Project Professionalism with the aim to describe in detail the aims and qualities of a professional. Six values were identified: altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honor, and integrity and respect for others.25 A subsequent collaboration between the ABIM, the American College of Physicians, the American Society of Internal Medicine and the European Federation of Internal Medicine resulted in the publication of the Physician’s Charter,26 the most widely accepted and acknowledged publication on professionalism.24 And while medicine served as the benchmark for considerations around professionalism,24 other health care areas such as nursing and pharmacy27 have expressed increased concern about professionalism in their students. Other occupations, such as veterinary science and dentistry, are beginning to call for consensus on a definition as well.28,29

The difficulties in agreeing on general professional attributes extend equally to the pharmacy profession,3,8,21,30 and there remains a lack of consensus as to what constitutes professionalism in the pharmacy arena.21,31 Hammer pointed out that professional traits were essential, but difficult to define and measure.5 In addition, exact characterization of the pharmacy professional has been in a state of flux as the practice of pharmacy evolves into an era requiring more interaction with patients and, therefore, greater focus on professional skills and attitudes.21,32 Evetts described the history of attempts to pin down the nature of professionalism in general and noted it is not a fixed construct and would continue to change over time.33 In its development of “A Global Framework for Quality Assurance of Pharmacy Education,” FIP presented the following definition of professionalism: “the ethics, attitudes, values, qualities, conduct, and behaviors that characterize a profession and are expected of its practitioners, and that underpin the trust that the public has in the profession.”2

One of the earliest responses to the changing landscape of the pharmacy profession was the collaboration between the American Pharmacists Association - Academy of Students of Pharmacy, and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy’s Council of Deans (APhA-ASP/AACP-COD) which resulted in the formation of a Task Force on Professionalism. The Task Force eventually published a white paper examining pharmacy student professionalism. The document defined 10 characteristics of a professional and 10 traits which would be exhibited by a professional pharmacist.34 This was followed by a toolkit that provided strategies for developing the professional traits amongst students.The white paper also included 3 documents to help define professionalism for the pharmacist and the pharmacy student: The Oath of a Pharmacist, the Code of Ethics for Pharmacists, and the Pledge of Professionalism.34 Hammer et al followed up with a comprehensive review of the issues surrounding student professional development and offered recommendations to university educators for the implementation of professional education within pharmacy programs.8

The publication of the white paper prompted an increase in research on professionalism.11 Much of the research identified professional attributes, beliefs, and values as indicators of professional development.5,35 In 2007, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) set out to define attributes of professionalism with the goal of helping students better understand it. Using a bicycle wheel, an analogy previously suggested by Hammer,8 professionalism was represented by a fiducial relationship between pharmacist and patient at the center of the wheel. Five spokes emerged from the center, each spoke representing a core trait of professionalism. The process involved an extensive literature review in the area of medicine, nursing, and pharmacy, as well as input from members of an ACCP working committee and an assessment by several professionals.

From this patient centered viewpoint came a 5-point description of professionalism in pharmacy: care and compassion, responsibility, honesty and integrity, respect for others, and commitment to excellence.36 The spokes of the wheel described the desired traits of a professional pharmacist ,which, in turn, lead to behaviors on the outer rim of the wheel, such as patient care.36 The attitudes, values ,and behaviors that epitomize professionalism were acknowledged as problematic, and the authors attested to the comprehensive list of professional characteristics identified by their research. It was their intent, however, to develop a manageable framework with which to guide student understanding and development. The most important aspect identified by the authors was a relationship built on trust with corresponding actions and behaviors and without which the profession would not exist.36

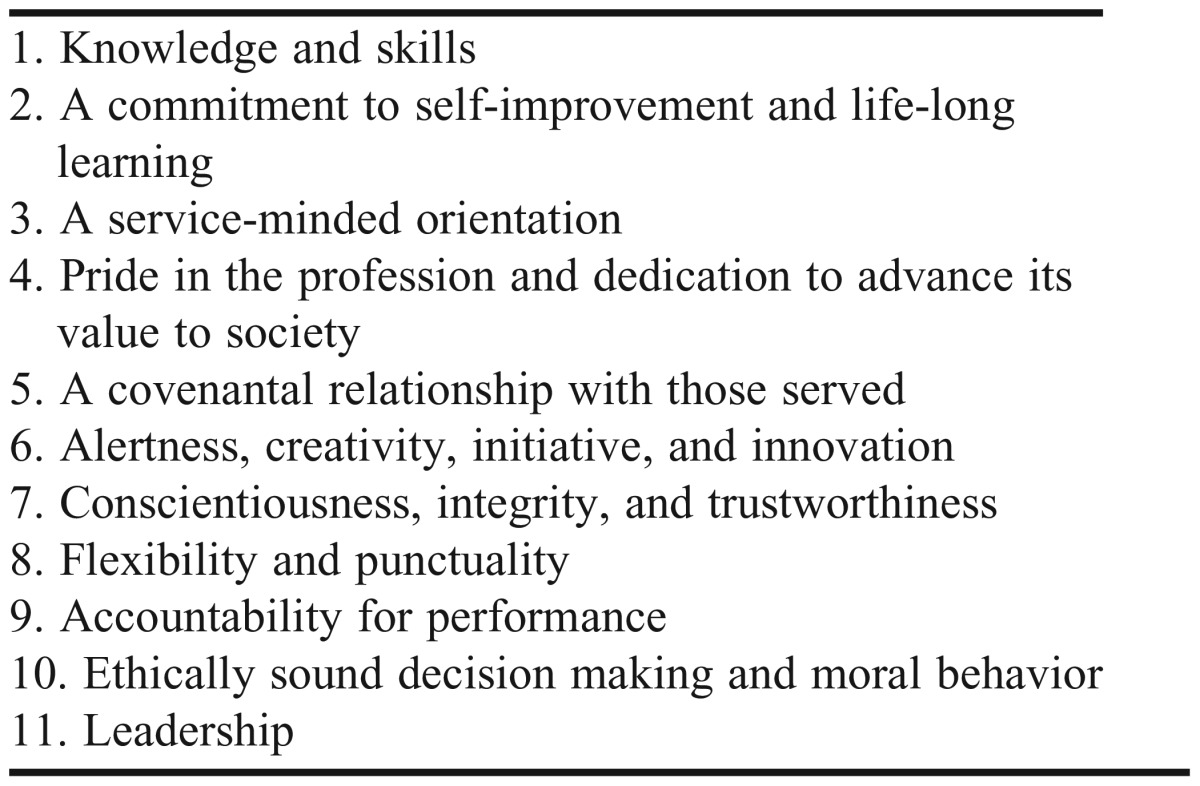

The Pharmacy Board of Australia released its latest code of conduct in March 2014.37 It outlined professional values and qualities that pharmacists should adopt. Once again, the patient was at the center of all activity, concurring with Holdford,14 who highlighted that professionalism could only be achieved when the patient was the central focus. The Australian viewpoint also drew particular attention to the need for cultural awareness, respect for patient diversity, and a greater focus on self-awareness and self-reflection.37 In 2011 the AACP professionalism task force revisited the 10 traits published in the 2000 white paper and added flexibility and punctuality as additional elements, as well as alertness, initiative, and integrity to create 11 traits of professionalism (Table 1). The authors also made 16 recommendations for nurturing professionalism in student pharmacists. Among these were implementation of training for educators, development of assessment tools, changes to admission processes to incorporate aspects of professionalism, updates to previous resources for educators, and development of leadership training within the curriculum.35

Table 1.

Professionalism Traits as Identified by the AACP Professionalism Task Force35

PROFESSIONALIZATION AND IDENTITY

The process of becoming a professional is called “professional socialization” or “professionalization” and is an essential component of health education.38 It involves a transformation of the self over time. Merton described professional socialization as: “…the transformation of individuals from students to professionals who understand the values, attitudes and behaviors of the profession deep in their soul. It is an active process that must be nurtured throughout the professional’s/student’s development.”39

In medical education the term “professional formation” is used to describe professionalization, indicating a reference to the tradition of educating clergy. Specifically the 475-year-old tradition of Jesuit formation is used as an example where core training involves service, experience, attainment of knowledge, and a reflection on the inner self. These activities are focused on the call to help others.15,40 The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching defined professional formation in terms of 3 apprenticeships: cognitive, practical, and professional formation. The last is further described as that which “introduces students to the purposes and attitudes that are guided by the values for which the professional community is responsible.”41

The process of professionalization, which occurs both during education and practice,34 is referred to as professional identity formation (PIF), reflecting the importance of identity to the process.42 The AACP White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism specifically mentioned the development of professional identity as part of the professionalization process.34 Many students arrive on the first day of the course as having already commenced professional identity development.43,44 This would be especially true of students who seek employment in pharmacies before starting formal university training.45 However, once the student commences study, subsequent professional identity development may be delayed until the scientific basis to pharmacy practice has been mastered.46 Professional identity formation is attracting increasing attention as an essential element of professional socialization in medical education40,47,48 and is described as “the establishment of core values, moral principles, and self-awareness.”40 Goldie viewed the development of a professional identity as essential to the practice of medicine. He also linked low professional identity to underperforming students, which can lead to low retention of these students.6

Professionalization is a complex process unique to each individual influenced by the context and environment in which the development takes place.40,49 This idea was supported by several authors, who suggested a strong link between socialization and identity formation.50,51 Dall’Alba referred to professionalization as a transformation involving an “embodiment of understanding of practice” and added that it is critical during this transition period that students have the opportunity to consider “ways of being” as they reflect on who they are becoming, as well as what they know and what they can do.7 She noted professional development programs focus overwhelmingly on the acquisition of knowledge and skills and that this is inadequate for the transformation required in becoming a professional.7 Focusing solely on skills and creating specific measurable competencies may compromise the realization of richness, depth, and interconnectedness of professionalism.50,52

PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION

A significant body of work exists regarding teaching professionalism instead of professional identity and it proposes important recommendations. In his publication Teaching Professionalism: Theory, Principles and Practices, Cruess outlined key recommendations for institutions introducing a professional education program in the area of medical education.53 He advised that professionalism must be taught explicitly from the first day of the program and continued throughout the course structure, a viewpoint supported by other research.8,13,30,54-56 The program must begin with an agreed definition of professionalism, which may differ at each institution.23,53,57-59 This can be problematic. He explored 8 areas for attention in the design of such a program. These included experiential learning, institutional support, and evaluation. Moreover, Cruess placed particular emphasis on the creation of an environment conducive to professional socialization. He cautioned that aspects of the informal or hidden curriculum may work against positive professional acculturation.53 Cruess also draws particular attention to the power of role modeling as a teaching tool, calling it “the most potent means of transmitting those intangibles called the art of medicine,”53 Others have similarly identified the value of role modeling in professional education.6,40,60-62

In pharmacy education, Schafheutle et al espoused the value of practice-based experiences to the development of professionalism.63 In 2007 the US Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) recognized the importance of experiential learning and released new standards64 for introductory and advanced practice experiences which remain an integral part of the current standards – Standards 2016.65 The standard requires a minimum of 300 hours of practice experiences to be incorporated into doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs. Subsequent related work has sought to provide support to preceptors as they train students in these settings45 and assessment protocols to assist student understanding of professional expectations.10

Hammer et al described aspects of pharmacy education that influenced the professional development process in student pharmacists including professional competence, mentoring and modelling, school culture and environment, extra-curricular activities, personal values, communication, and empathy.8 The authors provided general and specific recommendations for educators designing professional education programs extending from recruitment and admissions through to curriculum design and assessment.8

Sylvia conducted an analysis of response by US pharmacy schools and colleges to such recommendations.66 Schools were surveyed to determine the extent of the uptake of the recommendations in areas such as recruitment, admissions, educational programs, and practice. While white-coat ceremonies and student participation in professional organizations were common, less than 50% of the responding schools employed a mentoring program, utilized professional portfolios, or conducted dedicated professional development studies. The study revealed a need for an agreed upon definition of professionalism and standardized assessment instruments for the advancement of professional education.66

The 2016 ACPE Accreditation Standards for PharmD programs, or “Standards 2016,”65 identify professional development as one of 4 main educational outcomes in the PharmD. Central to professional development in accredited PharmD programs are introductory and advanced professional practice experiences (IPPE/APPE). These practice-based experiences allow students to interact with both practitioners and patients, thus progressively enriching their professional knowledge and skill base. Standards 2016 also requires that students experience the practice of pharmacy in a variety of health care settings and amongst other professionals involved with patient care. Through these initiatives it is envisioned that students will be practice ready and capable of working in multi-disciplinary teams.65

PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY AND HIGHER EDUCATION

According to Trede et al’s review, there was a lack of research on professional identity development in higher education.67 The authors reported identity development as “an underdeveloped field where there is little agreement between scholars.”67 The role of universities was discussed and, while research activity was low, the dominant viewpoint was that learning directly from the practice is crucial to identity development.67,68 Research supports the importance of experiential learning in the education of health professionals.35,67,69,70 Professional identity development also has an important role in the professionalization of students13,32,48,68 Dall’Alba, for example, considered the process of becoming professional to involve thinking, acting, and being like a professional,7 a position which highlights the importance of students being given opportunities to directly engage with and reflect on aspects of professional practice.7,71

The Trede et al review also called for research into achieving a greater understanding of identity development to inform teaching, learning, and assessment of professionalism. Regarding the last, the absence of concrete concepts and accurate measures makes assessing professionalism complex.3,11,72 The lack of an agreed upon definition for pharmacy professionalism means there is little work in the literature on appropriate assessment tools.11 Research to date focuses on generating assessment tools designed around professional attitudes and behaviors.73-75 In their paper on assessing professionalism, Aguilar et al discussed the strengths and weaknesses of using attitudes, values, and behaviors as indicators. They concluded it would be ideal to assess professionalism on all 3 fronts, but conceded that this may be unrealistic because of existing academic workloads. They recommended the assessment of attitudes using attitudinal scales, as such scales are simple to conduct and more reflective of the student’s professional development than values or behaviors.3

There are inherent difficulties regarding conclusions about student professionalism based on attitudes, values, and behaviors. As Hammer suggested, “acting professionally is not the same as being a professional.”8 Kelley et al72 developed a Professional Assessment Tool (PAT), an instrument measuring behavioral aspects of professionalism. The 9-item McLeod Clarke Professional Identity Scale (MCPIS)62 measures identity, was based on an instrument by Adams et al43 and tested and validated in the discipline of nursing.

Trede et al reported that it is important to adopt teaching strategies that encourage students to actively develop facets of professional identity. They also revealed that some research saw professional identity development as being the responsibility of the students.67 Trede et al commented on the need for a more unified and consistent approach and recommended that “universities need to claim their role in professional identity development to prepare graduates for global citizenship, for leadership qualities and for future practice.”67

Reid et al’s study, conducted across a range of professional disciplines in Sweden and Australia, reported that professional identity development was a way for higher education to prepare students for work.76 The authors explained that opportunities for “blurring the boundaries between the academy and work” facilitated identity formation and provided students with knowledge of the profession. They suggested 4 strategies for blurring the boundaries: (1) involvement of professionals with higher education; (2) involvement of students in work situations; (3) alignment of learning with authentic work practices; and (4) approach of interprofessional learning. In addition, the authors recommended that attention also be paid to the sense of profession created around a particular area of study, and its potential effect on student professional identity development.48,76 The authors believed the more authentic the activity, the greater the influence on professional identity development.76 Their work is in agreement with that of Lave and Wenger on communities of practice,77 where professional identity development occurs through student participation in and interaction with professional work settings.

As a result of their work, Reid et al developed a model of professional identity development describing it as a function of “knowledge for the profession” and “learning for professional work.” The potential outcome of these 2 factors is engagement and subsequent identity formation. Part of this process was referred to by the authors as the development of “sensitizing dispositions,” which orient students within their profession by placing them in context professionally and personally. In their model, these dispositions represent the link between the 2 dimensions of their model. They not only equip the students with the knowledge basis of their studies, but also broaden their professional repertoire to include a level of meaning intrinsic to professional activity.76

The ultimate aim of the model is for students to realize and internalize the connection between their individual and professional selves, otherwise defined as the ontological dimension of professional development.76 This agrees with the work of Dall’Alba, who, in her description of individual trajectories towards professionalization, stated that educational programs often fail to address these differences in their teaching approaches.78 Reid et al suggested that student learning trajectories “are influenced by the ways that the sense of profession is communicated and articulated to students through the design and pedagogy of the educational program.”48 Branch proposed the development of professional identity would be optimal when a combination of teaching methods were employed over an extended period across the curriculum.79 Experiential learning, critical reflection, and small group learning should feature in curriculum design as a combined model and extend long-term over the course structure.79

PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY AND PHARMACY

Schafheutle et al conducted a large study on the common approaches to professional education adopted by pharmacy schools in the United Kingdom. A review of teaching practices and program design looked specifically at how professionalism is acquired in 3 master of pharmacy (MPharm) courses. The researcher compared the approaches of 3 different schools using triangulation methods and curriculum mapping to reveal strategies for teaching professionalism. The importance of role models and practice experience emerged as essential elements in the professional socialization process. Exposure to pharmacists practicing in the settings and academics with ongoing patient contact were most important.30 The value of the early formation of professional identity was highlighted.

According to Schafheutle et al, professionalism is most effectively achieved through profession-related activity such as dispensing sessions, problem-solving activities, and role playing.13,30 Student professionalisation was also positively influenced through interactions with “patient-facing” teaching staff,13 those pharmacist educators who regularly work in hospital or community pharmacy.80

Trede et al also lent support to these results in their comments on the importance of authentic experiences for professional identity development.67 A large component of experiential learning in the curriculum, such as that stipulated by ACPE Standards 2016, provides a rich environment for student identity development through concentrated exposure to and engagement with the practice.

Stakeholders in the pharmacy profession are active in driving the cultivation of quality professionals on a global scale. Established in 2001 and controlled by the academic section of FIP, the International Forum for Quality Assurance of Pharmacy Education aimed to advance pharmacy education through the development of a quality assurance framework. The 2014 version of the framework recommended that pharmacy curriculum include exposure to the practice, as such experiences serve to enhance student professional identity development.2 The framework quotes The World Health Report that stated students who engage in practical experiences show “increase in empathy towards people with illnesses, have greater self-confidence and professional identity, and have learned effectively from the knowledge, attitudes, values, behaviors, and judgments of experienced practitioners.”81

Hammer noted that students develop professionally as a result of influences from many aspects of their educational experience. The design of the curriculum, placement experiences, teaching staff and professional representatives, and the overall culture established at the school serve to mold students toward their professional selves.8 Schafheutle et al group influences on professionalism development into the “intended, taught, and received” aspects of the curriculum. They suggest the greater the overlap or agreement between the 3 domains, the more effective the professional program will be.82

Australian pharmacy education researchers investigated the role curriculum plays in the development of student professional identity. Noble et al reported that identity development was an important part of educating pharmacists.32 Using a qualitative ethnographic study of each year of an undergraduate pharmacy course over a period of 4 weeks, the authors found there were few opportunities for students to engage and experiment with their pharmacist selves. The authors discussed strategies for identity development including opportunities for experiences with the practice, interactions with practicing pharmacists, and an emphasis on patient-centeredness in the curriculum. In addition, the authors identified the value of regular feedback in facilitating identity formation. Their research reported limited exposure to pharmacist role models and little opportunity for students to evaluate their own professional identity.32 These deficiencies in current curriculum approaches need to be addressed if future graduates are to be adequately prepared for the demands of health care. Trede et al contributed to the discussion by suggesting that educators also needed to recognize that professional identity was not a fixed construct and that students also needed an awareness of the changing nature of their identity as it responded to forces within the modern professional working context.67

CONCLUSION

The professionalization of students in health education is receiving increased attention, with concerns surrounding student conduct, work-ready graduates, and increasing demands of a career in health care. As pharmacy moves towards advanced practices and the complexity of the role increases, a corresponding amelioration of educational approaches to professionalization is required. The process of professionalization needs to reflect the complexity of professionalism, moving beyond the demonstration of desirable behaviors, attitudes, and values to a more holistic approach of professional identity formation.

Identity development research reports the value of authentic activities, such as patient-facing professionals as role models, experiential learning, and curriculum alignment with work practices. Curriculum design can exert a significant influence on student identity development, so it is important to consider these educational strategies for identity formation. Educators could place the idea of professional identity in the minds of new students as something that would chart their transition to a practicing professional and beyond. Further research is needed in professional identity development to better inform both effective teaching approaches and assessment strategies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) Quality Assurance of Pharmacy Education: the FIP Global Framework. 2014; 2nd ed: http://fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/Quality_Assurance/QA_Framework_2nd_Edition_online_version.pdf Accessed December 2, 2014.

- 3.Aguilar AE, Stupans L, Scutter S. Assessing students' professionalism: considering professionalism's diverging definitions. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2011;24(3):599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching professionalism: general principles. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):205–208. doi: 10.1080/01421590600643653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammer DP. Professional attitudes and behaviors: the “A’s” and “B’s” of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:455–464. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):e641–648. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dall'Alba G. Learning professional ways of being: ambiguities of becoming. Educ Philos Theory. 2009;41(1):34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Teaching Professionalism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

- 10.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Morgan JA. Rodriguez de Bittner M. Professionalism: a determining factor in experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;(2):71. doi: 10.5688/aj710231. Article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutter PM, Duncan G. Can professionalism be measured? evidence from the pharmacy literature. Pharm Pract. 2010;8(1):18–28. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wearn A, Wilson H, Hawken SJ, Child S, Mitchell CJ. In search of professionalism: implications for medical education. N Z Med J. 2010;123(1314):123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafheutle E, Hassell K, Ashcroft D, Hall J, Harrison S. Professionalism in Pharmacy Education. London 2010.

- 14.Holdford DA. Is a pharmacy student the customer or the product? Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(1):3. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabow MW, Remen RN, Parmelee DX, Inui TS. Professional formation: extending medicine's lineage of service into the next century. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):310–317. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c887f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waterfield J. Is pharmacy a knowledge-based profession? Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;(3):74. doi: 10.5688/aj740350. Article 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Queensland Government. Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Queensland). 2014. https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/LEGISLTN/CURRENT/H/HealthPracRNatLaw.pdf. Accessed December 29 2014.

- 18.Hafferty FW, Levinson D. Moving beyond nostalgia and motives: towards a complexity science view of medical professionalism. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):599–615. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van de Camp K, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Grol RP, Bottema BJ. How to conceptualise professionalism: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2004;26(8):696–702. doi: 10.1080/01421590400019518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Mook WN, van Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, et al. The concepts of professionalism and professional behaviour: conflicts in both definition and learning outcomes. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(4):e85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson S, Tordoff A., Beckett G. Pharmacy professionalism: a systematic analysis of contemporary literature (1998-2009) Pharm Educ. 2010;10(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley S, Kumar N. Teaching medical professionalism. Clin Med. 2012;12(1):9–11. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monrouxe LV, Rees CE, Hu W. Differences in medical students’ explicit discourses of professionalism: acting, representing, becoming. Med Educ. 2011;45(6):585–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hafferty FW. Definitions of professionalism: a search for meaning and identity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:193–204. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229273.20829.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Board of Internal medicine. Project Professionalism. Philadelphia PA; 1995.

- 26.ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Traulsen JM, Bissel P. Theories of professions and the pharmacist. Int J Pharm Pract. 2004;12(2):107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zijlstra-Shaw S, Robinson PG, Roberts T. Assessing professionalism within dental education; the need for a definition. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16(1):e128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2011.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossop LH. Is it time to define veterinary professionalism? J Vet Med Educ. 2012;39(1):93–100. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0411.041R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Ashcroft DM, Hall J, Harrison S. How do pharmacy students learn professionalism? Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20(2):118–128. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2011.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown D, Ferrill MJ. The taxonomy of professionalism: reframing the academic pursuit of professional development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):68. doi: 10.5688/aj730468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noble C, O’Brien M, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: Students’ perceptions of their curricular experience and professional identity formation. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2014;6(3):327–339. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evetts J. Professionalism: Value and ideology. Current Sociology. September 1, 2013 2013;61(5-6):778–796.

- 34.APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AACP Task Force on Professionalism. Report of the AACP Professionalism Task Force. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;10.

- 36.Roth MT, Zlatic TD. Development of student professionalism. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(6):749–756. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pharmacy Board of Australia. Code of Conduct. 2014; http://www.pharmacyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines/Code-of-conduct.aspx. Accessed November 12, 2014.

- 38.Arndt J, King S, Suter E, Mazonde J, Taylor E, Arthur N. Socialization in health education: encouraging an integrated interprofessional socialization process. J Allied Health. 2009;38(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merton RK RG, Kendall PL. The Student-Physician; Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J. Professional identity formation in medical education: The convergence of multiple domains. HEC forum:an interdisciplinary journal on hospitals' ethical and legal issues. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Hamilton NW. Fostering professional formation (professionalism): lessons from the Carnegie Foundation’s five studies on educating professionals. Creighton Law Review. 2011;Paper No. 11–21.

- 42.Inui TS. Flag in the wind: Educating for professionalism in medicine. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2003.

- 43.Adams K, Hean S, Sturgis P, Macleod Clark J. Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learning in Health and Social Care. 2006;5(2):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson M, Cowin LS, Wilson I, Young H. Professional identity and nursing: contemporary theoretical developments and future research challenges. International Nursing Review. 2012;59(4):562–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hammer D. Improving student professionalism during experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;(3):70. doi: 10.5688/aj700359. Article 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor KM, Harding G. The pharmacy degree: the student experience of professional training. Pharm Educ. 2007;7(1):83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasir NS, Stevens R, Kaplan A. Identity as a lens on learning in the disciplines In: K. Gomez LLJRe, ed. Learning in the Disciplines, Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS): Chicago, IL; 2010.

- 48.Reid A, Dahlgren LO, Petocz P, Dahlgren MA. Identity and engagement for professional formation. Studies in Higher Educ. 2008;33(6):729–742. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Health Professions Council. Professionalism in Healthcare Professionals. London 2011.

- 50.Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012:1185–1190. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faulk DR, Parker FM, Morris AH. Reforming perspectives: MSN graduates' knowledge, attitudes and awareness of self-transformation. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2010;7:Article24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Dall'alba G, Sandberg J. Educating for competence in professional practice. Instr Sci. 1996;24(6):411–437. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cruess RL. Teaching professionalism: theory, principles, and practices. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:177–185. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229274.28452.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thampy H, Gwynne C, Foulkes R, Codd R, Burling S. Teach professionalism. Education for Primary Care: An Official Publication of the Association of Course Organisers, National Association of GP Tutors, World Organisation of Family Doctors. 2012;23(4):297–299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce: Enabling Concerted and Collective Global Action. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;(6):72. doi: 10.5688/aj7206127. Article 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lesser CS, Lucey CR, Egener B, Braddock CH, Linas SL, Levinson W. A behavioral and systems view of professionalism. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2732–2737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinert Y, Cruess S, Cruess R, Snell L. Faculty development for teaching and evaluating professionalism: from programme design to curriculum change. Med Educ. 2005;39(2):127–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hall J, Ashcroft D. What characterises professionalism in pharmacy students? A nominal group study. Pharm Educ. 2011;(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(1):74–76. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldie J, Dowie A, Cotton P, Morrison J. Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):610–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pratt MG, Rockmann KW, Kaufmann JB. Constructing professional identity: the role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. The Academy of Management Journal. 2006;49(2):235–262. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Worthington M, Salamonson Y, Weaver R, Cleary M. Predictive validity of the Macleod Clark Professional Identity Scale for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2012;33(3):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schafheutle E, Hassell K, Ashcroft D, Hall J. Learning professionalism through practice exposure and role models. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2010;(7):285. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. 2011; https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf.

- 65.Sylvia LM. Enhancing Professionalism of pharmacy students: results of a national survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;(4):68. Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and Key Elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Chicago, Ill: ACPE; 2015; https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf.

- 67.Trede F, Macklin R, Bridges D. Professional identity development: a review of the higher education literature. Studies in Higher Educ. 2012;37(3):365–384. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stupans I, Owen S. Comprehensive curriculum planning to improve student learning in experiential learning placements. The Student Experience, Proceedings of the 32nd HERDSA Annual Conference. Darwin: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia; 2009:398–406.

- 69.Chalmers RK, Adler D, Haddad AH, Hoffman S, Johnson KA, Woodard J. The essential linkage of professional socialization and pharmaceutical care. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;(1):59. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cornelissen JJ, Van Wyk AS. Professional socialisation : an influence on professional development and role definition. S African J of Higher Educ. 2007;21(7):826–841. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dall’Alba G, Sandberg J. Unveiling professional development: a critical review of stage models. Rev Educ Res. 2006;76(3):383–412. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelley KA, Stanke LD, Rabi SM, Kuba SE, Janke KK. Cross-validation of an instrument for measuring professionalism behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;(9):75. doi: 10.5688/ajpe759179. Article 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hammer DP, Mason HL, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(2):141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;(4):70. doi: 10.5688/aj700485. Article 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Duke LJ, Kennedy WK, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Sheffield MC, Chisholm MA. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;(5):69. Article104. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reid A, Abrandt Dahlgren M, Petocz P, Dahlgren LO. From Expert Student to Novice Professional. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011.

- 77.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- 78.Dall’Alba G. Learning to be Professionals. Vol. 4. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009.

- 79.Branch WT. Teaching professional and humanistic values: suggestion for a practical and theoretical model. Patient Educ Couns. 2015(0). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Noyce PR. Ensuring continuing fitness to practice in the pharmacy workforce: Understanding the challenges of revalidation. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2013;9(2):199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.World Health Organisation. The World Health Report 2006: Working together for health. 2006; http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en. Accessed November 12 2014.

- 82.Schafheutle EI, Hassell K, Ashcroft DM, Harrison S. Organizational philosophy as a new perspective on understanding the learning of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(10):Article 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]