Abstract

This study evaluated the antifungal susceptibility profile and the production of potential virulence attributes in a clinical strain of Candida nivariensis for the first time in Brazil, as identified by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS)1-5.8S-ITS2 region and D1/D2 domains of the 28S of the rDNA. For comparative purposes, tests were also performed with reference strains. All strains presented low planktonic minimal inhibitory concentrations (PMICs) to amphotericin B (AMB), caspofungin (CAS), and voriconazole. However, our strain showed elevated planktonic MICs to posaconazole (POS) and itraconazole, in addition to fluconazole resistance. Adherence to inert surfaces was conducted onto glass and polystyrene. The biofilm formation and antifungal susceptibility on biofilm-growing cells were evaluated by crystal violet staining and a XTT reduction assay. All fungal strains were able to bind both tested surfaces and form biofilm, with a binding preference to polystyrene (p < 0.001). AMB promoted significant reductions (≈50%) in biofilm production by our C. nivariensis strain using both methodologies. This reduction was also observed for CAS and POS, but only in the XTT assay. All strains were excellent protease producers and moderate phytase producers, but lipases were not detected. This study reinforces the pathogenic potential of C. nivariensis and its possible resistance profile to the azolic drugs generally used for candidiasis management.

Keywords: Candida nivariensis, Brazil, antifungal resistance, hydrolytic enzymes, adherence, biofilm

Candida glabrata is an emerging pathogen in public and private Brazilian hospitals (Colombo et al. 2013). Moreover, it is the most common species of invasive fungal infections among non-albicans Candidaspecies in North America (Lockhart et al. 2012, Pfaller et al. 2014) and Central Europe (De Luca et al. 2012, Milazzo et al. 2014). Based on molecular analysis, two new species that are closely related to and phenotypically resemble C. glabrata have been described: Candida nivariensis andCandida bracarensis (Alcoba-Flórez et al. 2005b, Correia et al. 2006). C. nivariensiswas first described in 2005 after it was isolated from clinical samples (bronchoalveolar lavage, blood culture, and urine) from three patients in the Canary Islands, which are African islands under Spanish rule (Alcoba-Flórez et al. 2005b). MALDI-TOF analyses were later demonstrated to be an efficient tool to differentiate these species (Gorton et al. 2013). Since then, other cases have been reported in Europe (Borman et al. 2008, Gorton et al. 2013, López-Soria et al. 2013, Swoboda-Kopeć et al. 2014), Asia (Fujita et al. 2007, Wahyuningsih et al. 2008, Chowdhary et al. 2010, Sharma et al. 2013, Li et al. 2014, Tay et al. 2014,Feng et al. 2015), and Australia (Lockhart et al. 2009). The total number ofC. nivariensis isolates described in the literature has been low in these countries. To the best of our knowledge, the isolation of C. nivariensis in clinical samples has not been reported to date in countries of North America and South America.

C. nivariensis isolates are less susceptible than C. glabrataisolates to the azolic antifungal agents [fluconazole (FLC), itraconazole (ITR), and voriconazole (VRC)] that are commonly used in the treatment of candidiasis (Borman et al. 2008). Thus, a periodic monitoring of this species is necessary to determine its antifungal resistance profile (Fujita et al. 2007, Borman et al. 2008).

Virulence factors play a crucial role in the colonisation, adhesion, invasion, dissemination, and escape from host defences. Compared with C. albicans, few studies have addressed the expression of virulence factors inC. glabrata, including the adhesion of the organism to host cells and/or tissues as well as medical device surfaces, biofilm formation, and the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., proteases, lipases, and haemolysins) (Silva et al. 2012). Furthermore, very little is known about the virulence attributes of C. nivariensis (Fujita et al. 2007).

Based on the scarce knowledge of this pathogen, the present study aimed to evaluate the antifungal susceptibility profile and the production of virulence attributes in a clinical strain of C. nivariensis isolated from a hospital in Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil. In parallel, two reference strains were included with the aim of comparing the evaluated phenotypic markers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains, growth conditions, and biochemical identification - We analysed a clinical fungal strain obtained from a patient from a public hospital of RJ who was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with lesions in the nasal cavities. The clinical strain [893391 strain/Brazilian National Cancer Institute (INCA)] was isolated from a nasal secretion in 2004 and was identified by API 20 C AUX (bioMérieux, France) as C. glabrata. This strain was sent to the Mycology Laboratory of the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, RJ, for further study. This fungal isolate was grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar and Chromagar Candida medium (both at 37ºC for 48 h) to evaluate its viability and purity, respectively. The confirmation of species was achieved by biochemical analysis with the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux) using a YST card according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. In addition, two reference strains were included, C. nivariensis WM 09.150 and C. glabrata ATCC 2001, for comparative purposes.

Molecular identification - Yeast cells were recovered from Sabouraud dextrose agar and used for DNA extraction with the Gentra®Puregene® Yeast and G+ Bacteria Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The clinical strain was identified by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer (ITS)1-5.8S-ITS2 region and D1/D2 domains of the 28S of the rDNA as previously described (Alcoba-Flórez et al. 2005b). Sequences were edited using SequencherTM v.4.9 and compared by BLAST with sequences that were available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information/GenBank database. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the MEGA 4.0.2 software (Tamura et al. 2007).

Antifungal susceptibility testing against planktonic cells - In vitro antifungal susceptibility testing against planktonic cells was performed according to the recommendations proposed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A3 protocol (CLSI 2008a). Amphotericin B (AMB), posaconazole (POS), caspofungin (CAS), FLC, ITR, and VRC (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Corporation, USA) were tested. Briefly, RPMI-1640 medium with L-glutamine and without bicarbonate (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, The Netherlands), buffered with 0.165 M 3-N-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) at pH 7, was used for the broth microdilution test. The inoculum was prepared from a 24-h fresh Sabouraud dextrose agar culture; the cells were harvested in RPMI medium and diluted to approximately 1-5 × 103 cells mL-1. The plates were incubated at 35ºC for 24 h. The minimal inhibitory concentrations of the drugs on planktonic cells (PMICs) were determined according to the CLSI M27-A3/ M27-S3 protocol (CLSI 2008a, b).

Production of hydrolytic enzymes - The in vitro production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes was measured using plate assays (Price et al. 1982). Briefly, protease activity was evaluated using yeast carbon base supplemented with bovine serum albumin (Rüchel et al. 1982), phytase activity was evaluated using the calcium phytate agar plate (Tsang 2011), phospholipase activity was assessed using egg yolk agar plate (Price et al. 1982), esterase activity was determined using the Tween agar plate (Aktas et al. 2002), and haemolytic activity was assayed using the blood agar plate (Luo et al. 2001). In this set of experiments, aliquots (10 µL) of 48-h-old cultured fungal cells (1 × 107cells mL-1) were spotted on the surface of the agar medium and incubated at 37ºC for up to seven days. The diameter of the colony (a) and the diameter of the colony plus the precipitation zone (b) were measured using a digital paquimeter, and the enzymatic activities were expressed as the Pz value (a/b), as previously described (Price et al. 1982). According to this definition, low Pzvalues indicate high enzymatic production and, conversely, high Pzvalues indicate low enzymatic production. The enzymatic activity was scored into four categories: a Pz of 1.0 indicated no enzymatic activity, aPz between 0.999-0.700 indicated low enzymatic activity, aPz between 0.699-0.400 indicated moderate enzymatic activity, and a Pz between 0.399-0.100 indicated high enzymatic activity (Price et al. 1982).

Adhesion to abiotic substrates - The adherent ability to abiotic substrates was tested using glass and polystyrene. The glass slide were first washed with Extran for 2 h and 70% ethanol for 30 min and were then sterilised at 180ºC for 2 h. Fungal cells (1 × 106 cells mL-1) were placed on glass slides and on 24-well polystyrene plates and incubated at 37ºC for 1 h. Subsequently, the abiotic substrates were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove nonadherent cells. Five different microscopic fields were counted in each system to express the number of total fungi adhering to these substrates (Reinhart et al. 1985).

Production and antifungal susceptibility of biofilm-forming cells - Fungal cell suspensions were adjusted to 1 × 103 cells mL-1 in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose and transferred to 96-well polystyrene microtitre plates. The plates were incubated at 37ºC for 48 h to allow biofilm formation. The biomass formation was assessed using crystal violet (CV) staining and the viable cells in biofilm were measured using a colorimetric assay that investigates the metabolic reduction of 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) (Sigma-Aldrich) to a water-soluble brown formazan product (Peeters et al. 2008). Briefly, the wells were washed three times in PBS to remove nonadherent cells. An aliquot of 100 µL of 99% methanol was added to each well for 15 min to fix the biofilm, and then the supernatant was discarded. Microplates were air-dried and 200 µL of 0.4% CV solution was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The dye solution was discarded and the wells were washed with 200 µL of sterile distilled water. Finally, 150 µL of 33% acetic acid was added to the stained wells and the absorbance was measured at 590 nm. For the XTT reduction assay, a solution containing 200 µL PBS with 1 mg mL-1 XTT (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.4 mM menadione (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. The plate was incubated in the dark at 37ºC for 3 h. Thereafter, 100 µL of this solution was transferred to another microplate and the colorimetric change was measured at 492 nm using a microplate reader. After biofilm formation, the YNB medium was discarded and the wells were washed with 200 µL of PBS. Then, an aliquot of 100 µL of RPMI-1640 that was buffered with MOPS and supplemented with the antifungals prepared according to the CLSI M27-A3 protocol (CLSI 2008a) was added. The plates were incubated at 37ºC for 24 h. After this last incubation, the CV staining and XTT reduction assay were performed, as described above, to detect cell biomass and viability, respectively. The minimum biofilm eradication concentrations (MBECs) were determined as the lowest concentrations of the antifungal drug that were able to reduce at least 50% of cell biomass or viability compared with the drug free growth control well (Melo et al. 2011).

Statistical analysis - All experiments were performed at least twice. The data were analysed statistically in different experimental groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test. To compare data between groups, the Mann-WhitneyU test was used. p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v.17.0, for Windows®(SPSS Inc, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Initially, the identification of the clinical strain 893391/INCA was reconfirmed to certify its authenticity by mycology methodologies. The cultivation in chromogenic CHROMagar Candida medium generated white colonies with a smooth texture. Subsequently, both the carbohydrate assimilation and the metabolic enzymatic profiles were evaluated using the Vitek 2 system, which identified the clinical strain 893391/INCA as C. glabrata (98% probability). However, phenotypic tests were not able to discriminate among the three species of the C. glabrata complex; therefore, molecular methods were applied to confirm the identification of this clinical strain (Alcoba-Flórez et al. 2005b, Wahyuningsih et al. 2008, Romeo et al. 2009, Enache-Angoulvant et al. 2011, López-Soria et al. 2013).

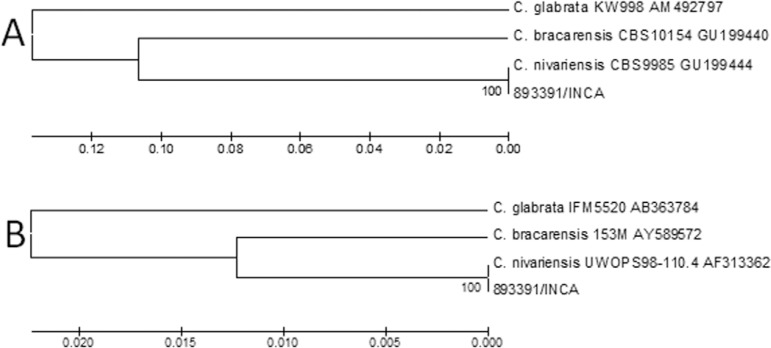

Genomic sequences obtained from our clinical strain showed 100% similarity with the GU199444 (ITS region) and AF313362 (D1/D2 domains) sequences found in the GenBank database, thus confirming its identity as C. nivariensis rather than C. glabrata (Figure). The obtained sequences with respect to the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region and D1/D2 domains of the 28S of the rDNA of the 893391/INCA strain were deposited in GenBank under the accessions KJ957824 and KJ957825, respectively.

Dendrograms based on analysis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) (A) and D1/D2 (B) regions of the 893391 strain and sequences from GenBank. The evolutionary histories of both trees were inferred using the UPGMA method. The percentage of replicate trees in with the associated taxon clustered in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is show next to the branches. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method and were in expressed as the number of base substitutions per site. There were 700 ITS and 580 D1/D2 positions in the final dataset.

According to a simple review of the current published literature (Alcoba-Flórez et al. 2005a, Fujita et al. 2007, Borman et al. 2008, Wahyuningsih et al. 2008, Lockhart et al. 2009, Chowdhary et al. 2010, Gorton et al. 2013, López-Soria et al. 2013, Sharma et al. 2013, Li et al. 2014, Swoboda-Kopeć et al. 2014,Tay et al. 2014, Feng et al. 2015), 55 isolates of C. nivariensis have been described in 35 cases in European countries, 19 cases in Asia, and one case report in Australia (Table I). Therefore, there are no cases of C. nivariensis in the American continent. Hence, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of C. nivariensis in South America, specifically in Brazil. C. nivariensis has been found in different clinical samples, including bronchoalveolar lavage, blood, urine, catheter, sputum, lung biopsy, pleural fluid, vaginal swab, toenail, and other clinical specimens, but until now, it has not been isolated from a nasal secretion as the 893391/INCA strain (Table I).

TABLE I. Candida nivariensis isolates described in the literature.

| Reference | Country | Total of isolates (n) | Source of isolates (n) | Clinical details | Susceptibility antifungal profile | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| S/low MIC | SDD/I | R/high MIC | |||||

| Alcoba-Flórez et al. (2005b) | Spain | 3 | Broncho-alveolar lavage (1), blood culture (1), urine (1) | Multiple pulmonary abscesses, pancreatic abscess, lumbar pain | Not stated | ||

| Fujita et al. (2007) | Japan | 1 | Catheter (1) | Rheumatoid arthritis | - | - | FLC |

| Wahyuningsih et al. (2008) | Indonesia | 1 | Oral rinse (1) | HIV infection | FLC, ITC, VRC and CAS/AMB, 5FC, POS, and ISA | - | - |

| Borman et al. (2008) | UK | 16 | Blood (3), oral cavity (3), pelvic abscess (2), ascetic fluid (1), peritoneal fluid (1), lung biopsy (1), not stated (5) | Oral candidosis, neutropaenia, pneumonia, malignancy, peritonitis, and others | - | - | FLC and ITC/5FC and VRC |

| Lockhart et al. (2009) | Australia | 1 | Pleural fluid (1) | Not stated | FLC | - | - |

| Chowdhary et al. (2010) | India | 2 | Sputum (1), blood (1) | HIV infection, diabetes | FLC, ITC, VRC and CAS/AMB, 5FC, and POS | - | - |

| López-Soria et al. (2013) | Spain | 2 | Blood (1), catheter (1) | Intestinal fistula associated to a severe malnutrition | Echinocandins, FLC, and VRC/AMB | ITC | - |

| Sharma et al. (2013) | India | 5 | High vaginal swab (4), bronchoalveolar lavage (1) | Vulvovaginal candidiasis, not stated | VRC, ITC and echinocandins/AMB, POS, and ISA | - | FLC |

| Gorton et al. (2013) | UK | 1 | Urine (1) | Renal transplant | - | - | FLC |

| Li et al. (2014) | China | 7 | Vaginal swab (7) | Vulvovaginal candidiasis | NYT | FLC, ITC, MCN, and CLT | - |

| Tay et al. (2014) | Malaysia | 2 | Blood culture (1), vaginal swab (1) | Not stated, vulvovaginal candidiasis | FLC, VRC, and CAS/AMB and POS | - | CLT |

| Swoboda-Kopeć et al. (2014) | Poland | 13 | Urine (8), lower respiratory tract (3), surgical specimens (1), body fluids (1) | Not stated | Not stated | ||

| Feng et al. (2015) | China | 1 | Toenail (1) | Not stated | FLC, VRC, and POS | - | ITC |

| Present paper (2015) | Brazil | 1 | Nasal secretion (1) | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | VRC and CAS/AMB | ITC | FLC/POS |

AMB: anfotericin B; CAS: caspofungin; CLT: clotrimazole; FLC: fluconazole; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; I: intermediate; ISA: isaconazole; ITC: itraconazole; MCN: iconazole; MIC: minimal inhibitory concentration; NYT: nistatina; POS: posaconazole; R: resistant; S: susceptible; SDD: susceptible-dose dependent; VRC: voriconazole; 5FC: flucytosine.

Concerning the antifungal susceptibility profile (Table II), both the C. nivariensis 893391/INCA strain and the reference strains presented low PMICs to AMB, CAS, and VRC. The low MICs to AMB, CAS, and VRC reported herein corroborate the results of previous studies (Chowdhary et al. 2010, Sharma et al. 2013, Gil-Alonso et al. 2015). However, only our strain showed elevated PMICs for POS and ITC as well as FLC resistance. In a study conducted by Borman et al. (2008), 16 isolates of C. nivariensiswere tested for seven antifungals, including POS and ITC. These isolates showed high PMIC values (2 and > 16 mg L-1, respectively) to these drugs. Similar results were found in the present study. Other studies also revealed high FLC PMICs (Fujita et al. 2007, Borman et al. 2008, Sharma et al. 2013) (64, 128, 16 mg L-1, respectively). Despite the lack of clinical breakpoints (CBP) and defined epidemiological cut-off values (ECV) for this species, C. nivariensishas been described in the literature as an emerging pathogenic fungus with a varying susceptibility to azoles (Borman et al. 2008). According to the CBP and ECV of its sibling species C. glabrata (Pfaller & Diekema 2012, Espinel-Ingroff et al. 2014), our strain would be resistant to FLC (PMIC ≥ 64 mg L-1) and non-wild type to FLC (ECV > 8 mg L-1) and POS (ECV > 1 mg L-1) (Table II).

TABLE II. Antifungal susceptibility of Candida nivariensis andCandida glabrata planktonic and sessile cells.

| Antifungals | PMIC (mg L-1)/susceptibility profilea | CV MBEC (mg L-1)/% reduction of biomass | XTT MBEC (mg L-1)/% reduction of viability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| C. nivariensis | C. glabrata | C. nivariensis | C. glabrata | C. nivariensis | C. glabrata | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| 893391/INCA | WM 09.150 | ATCC 2001 | 893391/INCA | WM 09.150 | ATCC 2001 | 893391/INCA | WM 09.150 | ATCC 2001 | |

| AMB | 0.25/NAb | 0.25/NAb | 0.12/NAb | ≥ 16/54.2 | ≥ 16/30.7 | ≥ 16/28.4 | ≥ 16/54 | ≥ 16/73.1 | ≥ 16/72.8 |

| CAS | 0.03/S | 0.12/S | 0.12/S | ≥ 8/31.6 | ≥ 8/22.8 | ≥ 8/40.4 | ≥ 8/63.7 | ≥ 8/0 | ≥ 8/79.8 |

| FLC | ≥ 64/R | 8/SDD | 8/SDD | ≥ 64/6.7 | ≥ 64/23.7 | ≥ 64/13.7 | ≥ 64/1.5 | ≥ 64/15 | ≥ 64/0 |

| ITC | 0.25/SDD | 0.06/S | 0.06/S | ≥ 16/19.1 | ≥ 16/31.1 | ≥ 16/1.7 | ≥ 16/16 | ≥ 16/0 | ≥ 16/10.7 |

| VRC | 0.25/S | 0.03/S | 0.03/S | ≥ 16/13.1 | ≥ 16/41.7 | ≥ 16/20.5 | ≥ 16/20 | ≥ 16/7 | ≥ 16/22 |

| POS | 2/NAc | 0.06/NAc | 0.03/NAc | ≥ 16/21.5 | ≥ 16/24.3 | ≥ 16/6.9 | ≥ 16/54.5 | ≥ 16/29.3 | ≥ 16/13.8 |

a: determined according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-S3 (CLSI 2008b); b: the CLSI has not defined interpretative cut-offs for amphotericin B (AMB). In general, isolates with AMB minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) >1 mg L-1 are likely to be resistant to this drug (CLSI 2008a); c: breakpoints not established by CLSI (CLSI 2008b, 2012); CAS: caspofungin; CLT: clotrimazole; CV: crystal violet; FLC: fluconazole; ITC: itraconazole; MBEC: minimum biofilm eradication concentration; NA: not applicable; PMIC: MIC of the drugs on planktonic cells; POS: posaconazole; R: resistant; S: susceptible; SDD: susceptible-dose dependent; VRC: voriconazole; XTT: 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide.

The pathogenicity of Candida species is associated with a multitude of virulence factors, including the ability to evade host defences, adhesion to host tissue and/or medical devices, the ability to form biofilm and the production of tissue-damaging hydrolytic enzymes such as proteases, lipases, and haemolysins (Silva et al. 2012). Along this line of thinking, we demonstrated that the C. nivariensis 893391/INCA strain, the C. nivariensis WM 09.150 reference strain, and theC. glabrata ATCC 2001 type strain were excellent protease producers (Table III), with no significant differences in the Pz values of these strains (p > 0.05). Jang et al. (2011) also found protease activity in six of 38 C. glabrata isolates from fresh feral pigeon faeces, but the production of proteases was moderate (mean Pz = 0.65 ± 0.17). Because C. glabrata does not possess classical secreted aspartic protease genes in its genome (Parra-Ortega et al. 2009, Silva et al. 2014), we believe that the enzymatic degradation of albumin verified herein may be due the production of yapsins (YPS). YPS are a family of five nonsecreted glycosylphosphatidyinositol (GPI)-linked aspartic proteases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that have homologues in C. glabrata, which have a well-known role in cell wall integrity (Krysan et al. 2005) and cell-cell interactions (Silva et al. 2014). The role of YPS-family proteases coded by 11 genes is known among the C. glabrata virulence factors that have been described. The expression of YPS genes significantly increases the capacity of the fungus to survive inside human macrophages (Krysan et al. 2005) . Swoboda-Kopeć et al. (2014) confirmed the prevalence of three genes (YPS2, YPS4, andYPS6) in the majority of C. glabrata strains isolated from clinical specimens. However, the prevalence of these genes in 13 clinical isolates of C. nivariensis was low (Swoboda-Kopeć et al. 2014). Regarding the phytase activity,C. nivariensis 893391/INCA strain and C. nivariensis WM 09.150 reference strain presented a moderate production of phytase, whereas the type strain of C. glabrata exhibited a low production of this enzyme (Table III). Phytase is a phosphohydrolase that cleaves phytate and releases inorganic phosphate and inositol, which are both essential nutrients for all living cells (Lei & Porres 2003). In Candidaspecies, such as the Candida parapsilosis complex (Abi-Chacra et al. 2013), maintaining a supply of inositol and phosphate mediated by phytase seems to be especially important for pathogen survival and persistence in the host (Tsang 2011). In this study, the three tested strains were negative for the production of phospholipase, esterase, and haemolysins under the employed experimental conditions. Udayalaxmi et al. (2014) did not find phospholipase activity in 14 C. glabratastrains isolated from the genitourinary tract, but all of their C. glabrata strains presented haemolytic activity.

TABLE III. Production of hydrolytic enzymes, adhesion to abiotic substrates, and biofilm formation detected in Candida nivariensis andCandida glabrata strains.

| Species/code | Hydrolytic activities | Adhesion to abiotic substrates (1 h) | Biofilm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Protease (P z)a | Phytase (P z)a | Glassb | Polystyreneb | Biomassc | Viabilityc | |

| C. nivariensis | ||||||

| 893391/INCA | 0.347 ± 0.040 | 0.629 ± 0.025 | 17.0 ± 4.4 | 25.4 ± 4.9 | 0.330 ± 0.045 | 1.173 ± 0.054 |

| WM 09.150 | 0.375 ± 0.000 | 0.634 ± 0.047 | 14.0 ± 3.0 | 23.9 ± 2.4 | 0.440 ± 0.095 | 0.811 ± 0.080 |

| C. glabrata | ||||||

| ATCC 2001 | 0.357 ± 0.034 | 0.714 ± 0.00 | 16.0 ± 3.0 | 24.1 ± 5.3 | 0.858 ± 0.009 | 1.084 ± 0.028 |

a: the protease and phytase activities were measured by the formation of a clear halo around the colony and expressed asPz value as previously described (Price et al. 1982) (thePz value was scored into four categories:Pz of 1.0 indicated no enzymatic activity,Pz between 0.999-0.700 indicated low enzymatic activity, Pz between 0.699-0.400 corresponded to moderate enzymatic activity, and Pz between 0.399-0.100 mean high enzymatic activity); b: the results were expressed as number of fungal cells per microscopic field; c: the biomass and viability of biofilm were measured by crystal violet incorporation at 540 nn and 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide reduction at 492 nm, respectively. All the results were reported as the arithmetic means ± standard deviation.

C. nivariensis 893391/INCA strain, as well as both reference strains, was able to bind to inert surfaces, with a predilection to polystyrene compared to glass (p < 0.001) (Table III). Adhesion is a crucial step for beginning and establishing an infectious process. The adhesive ability of Candida species is associated with the presence of specific cell-wall glycoproteins known as adhesins. The ability of C. glabrata to adhere to host epithelial tissue is mediated by a number of GPI-linked adhesion genes, including the EPA gene family (De Groot et al. 2008). In C. glabrata,the deletion of the EPA1 gene reduces the in vitro adhesion to epithelial cells, thus highlighting the essential role of this gene in adherence to biotic substrates (Cormack et al. 1999, d, de Las Peñas et al. 2003). In contrast, EPA6-mediated adhesion is engaged in strong hydrophobic interactions with abiotic surfaces and is the principal adhesin involved in biofilm formation (El-Kirat-Chatel et al. 2015).

Biofilm formation is considered to be an important virulence attribute ofCandida species and is associated with recurrent infections and treatment failures by limiting the penetration of drugs through the biofilm matrix (Mukherjee & Chandra 2004). In this study, C. glabrata ATCC 2001 type strain produced a significantly greater amount of biofilm biomass (p < 0.001) than did both C. nivariensis 893391/INCA and C. nivariensis WM 09.150 reference strain (Table III). The viability of cells forming biofilm showed a significant difference among C. nivariensis WM 09.150 and C. glabrata ATCC 2001 type strain (p < 0.05) as well as between 893391/INCA strain and WM 09.150 (p < 0.05) (Table III). Our strain, however, showed a biofilm profile of viability, as determined by the XTT assay, which was more related to the C. glabrata ATCC 2001 type strain (p > 0.05) (Table III). According to the literature,C. glabrata clinical isolates are capable of forming biofilm and their presence during the infection has been associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates compared with isolates that are unable to form biofilm (Kumamoto 2002).

To determine whether antifungal agents (AMB, CAS, FLC, ITC, VRC, and POS) could disarticulate the biofilms, they were exposed to different concentrations of antifungal agents. No significant reductions in the number of viable cells were observed for the lower concentrations of antifungal agents tested against the three analysed strains (data not shown). In the present study, the highest tested concentration of AMB, CAS, and POS (16, 8, and 16 mg L-1, respectively) was able to inhibit the viability of C. nivariensis 893391/INCA strain by more than 50% compared with the nontreated fungal cells. Similar results with these antifungal drugs were found for the C. nivariensis WM 09.150 reference strain and C. glabrata ATCC 2001 type strain. The reduction in viability for FLC, ITC, and VRC was low, at less than 30% for each of the strains. Concerning the total biomass (Table II), C. nivariensis 893391/INCA strain also presented a greater than 50% reduction of biomass at an AMB concentration of 16 mg/L. The highest concentrations of the other antifungal drugs yielded less than a 32% reduction in biomass for our clinical strain. The two reference strains presented less than a 42% reduction in biomass for all of the highest concentrations of the six tested antifungal drugs.

We observed that our MBECs values are much higher than PMICs values for all six tested antifungal drugs. Similar results were found for C. albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, andCandida metapsilosis (Melo et al. 2011). Fonseca et al. (2014)evaluated the effects of FLC on the formation and control of C. glabratabiofilm and they did not observe a reduction in the number of viable cells, even when antifungal drugs were applied at high concentrations. Therefore, further studies utilising higher antifungal concentrations are necessary to better determine the MBECs values of C. glabrata and C. nivariensisstrains.

The present study describes, for the first time, the isolation of C. nivariensis from an oncologic patient in Brazil and reports its potential antifungal resistance to FLC, which is the most common antifungal drug used for candidiasis treatment. As a warning, other countries in the Americas need to search for C. nivariensis by means of molecular methods in theirC. glabrata culture collections because standard biochemical analytical methods are not sufficient to properly identify C. niva- riensis.We strongly believe that the real incidence of C. nivariensisin our continent may be underestimated due to the lack of adequate molecular surveillance strategies.

In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the in vitro production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes and biofilm formation ability in clinical strain of C. nivariensis. Further studies are needed to monitor the frequency of this species in clinical isolates, their potential virulence factors, and their susceptibility to antifungals, mainly due to the phenomenon of azolic resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To Dr Joshua Nosanchuk, for editorial assistance and helpful comments, to Wieland Meyer, for providing the C. nivariensis WM 09.150 reference strain, to Marcel Treptow Ferreira, for statistical assistance. Automated sequencing was performed using the DNA sequencing platform (ABI-3730) (Applied Biosystems) (PDTIS/Fiocruz).

REFERENCES

- Abi-Chacra ÉA, Souza LO, Cruz LP, Braga-Silva LA, Gonçalves DS, Sodré CL, Ribeiro MD, Seabra SH, Figueiredo-Carvalho MH, Barbedo LS, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Ziccardi M, Santos AL. Phenotypical properties associated with virulence from clinical isolates belonging to the Candida parapsilosis complex. FEMS Yeast Res. 2013;13:831–848. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas E, Yigit N, Ayyildiz A. Esterase activity in various Candida species. J Int Med Res. 2002;30:322–324. doi: 10.1177/147323000203000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoba-Flórez J, Arévalo MP, González-Paredes FJ, Cano J, Guarro J, Pérez-Roth E, Méndez-Álvarez S. PCR protocol for specific identification of Candida nivariensis, a recently described pathogenic yeast. J Clin Microbiol. 2005a;43:6194–6196. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6194-6196.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoba-Flórez J, Méndez-Álvarez S, Cano J, Guarro J, Pérez-Roth E, del Pilar AM. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Candida nivariensis sp. nov., a possible new opportunistic fungus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005b;43:4107–4111. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4107-4111.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borman AM, Petch R, Linton CJ, Palmer MD, Bridge PD, Johnson EM. Candida nivariensis, an emerging pathogenic fungus with multidrug resistance to antifungal agents. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:933–938. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02116-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary A, Randhawa HS, Khan ZU, Ahmad S, Juneja S, Sharma B, Roy P, Sundar G, Joseph L. First isolations in India of Candida nivariensis, a globally emerging opportunistic pathogen. Med Mycol. 2010;48:416–420. doi: 10.1080/13693780903114231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard, CLSI document M-27A3. 3rd ed. CLSI, Wayne; 2008a. 40 pp [Google Scholar]

- CLSI - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Third informational supplement, CLSI document M27-S3. CLSI, Wayne; 2008b. 28 pp [Google Scholar]

- CLSI - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Fourth informational supplement, CLSI document M27-S4. CLSI, Wayne; 2012. 32 pp [Google Scholar]

- Colombo AL, Garnica M, Camargo LFA, da Cunha CA, Bandeira AC, Borghi D, Campos T, Senna AL, Didier MEV, Dias VC, Nucci M. Candida glabrata: an emerging pathogen in Brazilian tertiary care hospitals. Med Mycol. 2013;51:38–44. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.698024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Ghori N, Falkow S. An adhesin of the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata mediating adherence to human epithelial cells. Science. 1999;285:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia A, Sampaio P, James S, Pais C. Candida bracarensis sp. nov., a novel anamorphic yeast species phenotypically similar to Candida glabrata. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:313–317. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot PW, Kraneveld EA, Yin QY, Dekker HL, Gross U, Crielaard W, de Koster CG, Bader O, Klis FM, Weig M. The cell wall of the human pathogen Candida glabrata: differential incorporation of novel adhesion-like wall proteins. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1951–1964. doi: 10.1128/EC.00284-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de las Peñas A, Pan SJ, Castaño I, Alder J, Creqq R, Comarck BP. Virulence-related surface glycoproteins in the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata are encoded in subtelomeric clusters and subject to RAP1- and SIR-dependent transcriptional silencing. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2245–2258. doi: 10.1101/gad.1121003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca C, Guglielminetti M, Ferrario A, Calabr M, Casari E. Candidemia: species involved, virulence factors and antimycotic susceptibility. New Microbiol. 2012;35:459–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kirat-Chatel S, Beaussart A, Derclaye S, Alsteens D, Kucharíková S, Van Dijck P, Dufrêne YF. Force nanoscopy of hydrophobic interactions in the fungal pathogen Candida glabrata. ACS Nano. 2015;9:1648–1655. doi: 10.1021/nn506370f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enache-Angoulvant A, Guitard J, Grenouillet F, Martin T, Durrens P, Fairhead C, Hennequin C. Rapid discrimination between Candida glabrata, Candida nivariensis and Candida bracarensis by use of a singleplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3375–3379. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00688-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinel-Ingroff A, Pfaller MA, Bustamante B, Canton E, Fothergill A, Fuller J, González GM, Lass-Flörl C, Lockhart SR, Martín-Mazuelos E, Meis JF, Melhem MS, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pelaez T, Szeszs MW, St-Germain G, Bonfietti LX, Guarro J, Turnidge J. Multilaboratory study of epidemiological cutoff values for detection of resistance in eight Candida species to fluconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:2006–2012. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02615-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Ling B, Yang X, Liao W, Pan W, Yao Z. Molecular identification of Candida species isolated from onychomycosis in Shanghai, China. Mycopathologia. 2015;180:365–371. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca E, Silva S, Rodrigues CF, Alves CT, Azeredo J, Henriques M. Effects of fluconazole on Candida glabrata biofilms and its relationship with ABC transport gene expression. Biofouling. 2014;30:447–457. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2014.886108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S, Senda Y, Okusi T, Ota Y, Takada H, Yamada K, Kawano M. Catheter-related fungemia due to fluconazole-resistant Candida nivariensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3459–3461. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00727-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Alonso S, Jauregizar N, Cantón E, Eraso E, Quindós G. In vitro fungicidal activities of anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin against Candida glabrata, Candida bracarensis, and Candida nivariensis evaluated by time-kill studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3615–3618. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04474-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorton RL, Jones GL, Kibbler CC, Collier S. Candida nivariensis isolated from a renal transplant patient with persistent candiduria - Molecular identification using ITS PCR and MALDI-TOF. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2013;2:156–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang YH, Lee SJ, Lee JH, Chae HS, Kim SH, Choe NH. Prevalence of yeast-like fungi and evaluation of several virulence factors from feral pigeons in Seoul, Korea. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2011;52:367–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysan DJ, Ting EL, Abeijon C, Kroos L, Fuller RS. Yapins are a family of aspartyl proteases required for cell wall integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;4:1364–1374. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.8.1364-1374.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto CA. Candida biofilms. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:608–611. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XG, Porres JM. Phytase enzymology, applications, and biotechnology. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:1787–1794. doi: 10.1023/a:1026224101580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Shan Y, Fan S, Liu X. Prevalence of Candida nivariensis and Candida bracarensis in vulvovaginal candidiasis. Mycophatologia. 2014;178:279–283. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9800-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Bolden CB, Baughman W, Stein B, Hollick R, Park BJ, Chiller T. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida bloodstream isolates from population-based surveillance studies into two US cities from 2008 to 2011. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3435–3442. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01283-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart SR, Messer SA, Gherna M, Bishop JA, Merz WG, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Identification of Candida nivariensis and Candida bracarensis in a large global collection of Candida glabrata isolates: comparison to the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1216–1217. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02315-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Soria LM, Bereciartura E, Santamaría M, Soria LM, Hernández-Almaraz JL, Mularoni A, Nieto J, Montejo M. Primer caso de fungemia asociada a catéter por Candida nivariensis en la Península Ibérica. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2013;30:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G, Samaranayake LP, Yau JY. Candida species exhibit differential in vitro hemolytic activities. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2971–2974. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2971-2974.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo AS, Bizerra FC, Freymüller E, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Colombo AL. Biofilm production and evaluation of antifungal susceptibility amongst clinical Candida spp isolates including strains of the Candida parapsilosis complex. Med Mycol. 2011;49:253–262. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.530032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milazzo L, Peri AM, Mazzali C, Grande R, Cazzani C, Ricaboni D, Castelli A, Raimondi Candidaemia observed at a university hospital in Milan (northern Italy) and review of published studies from 2010 to 2014. Mycopathologia. 2014;78:227–241. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee PK, Chandra J. Candida biofilm resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Ortega B, Cruz-Torres H, Villa-Tanaca L, Hernández-Rodríguez C. Phylogeny and evolution of the aspartyl protease family from clinically relevant Candida species. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:505–512. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters E, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J Microbiol Methods. 2008;72:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller MA, Andes DR, Diekema DJ, Horn DL, Reboli AC, Rotstein C, Franks B, Azie NE. Epidemiology and outcomes of invasive candidiasis due to non-albicans species of Candida in 2,496 patients: data from the prospective antifungal therapy (PATH) registry 2004-2008. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Progress in antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida spp by use of Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods, 2010 to 2012. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2846–2856. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00937-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MF, Wilhinson ID, Gentry LO. Plate method for detection of phospholipase activity in Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1982;20:7–14. doi: 10.1080/00362178285380031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart H, Muller G, Sobel JD. Specificity and mechanism of in vitro adherence of Candida albicans. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1985;15:406–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo O, Scordino F, Pernice I, Lo Passo C, Criseo G. A multiplex PCR protocol for rapid identification of Candida glabrata and its phylogenetically related species Candida nivariensis and Candida bracarensis. J Microbiol Methods. 2009;79:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüchel R, Tegeler R, Trost M. Comparasion of secretory proteinases from different strains of Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1982;20:233–244. doi: 10.1080/00362178285380341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma C, Wankhede S, Muralidhar S, Prakash A, Singh PK, Kathuria S, Kumar DA, Khan N, Randhawa HS, Meis JF, Chowdhary A. Candida nivariensis as an etiologic agent of vulvovaginal candidiasis in a tertiary care hospital of New Delhi, India. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva NC, Nery JM, Dias AL. Aspartic proteinases of Candida spp: role in pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. Mycoses. 2014;57:1–11. doi: 10.1111/myc.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S, Negri M, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams DW, Azeredo J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida tropicalis: biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity, and antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:288–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda-Kopeć E, Sikora M, Golas M, Piskorska K, Gozdowski D, Netsvyetayeva I. Candida nivariensis in comparison to different phenotypes of Candida glabrata. Mycoses. 2014;57:747–753. doi: 10.1111/myc.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA 4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay ST, Lotfalikhani A, Sabet NS, Ponnampalavanar S, Sulaiman S, Na SL, Ng KP. Occurrence and characterization of Candida nivariensis from a culture collection of Candida glabrata clinical isolates in Malaysia. Mycophatologia. 2014;178:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9778-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang PW. Differential phytate utilization in Candida species. Mycophatologia. 2011;172:473–479. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udayalaxmi J, Jacob S, D’Souza D. Comparison between virulence factors of Candida albicans and non-albicans species of Candida isolated from genitourinary tract. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:15–17. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10121.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuningsih R, SahBandar IN, Theelen B, Hagen F, Poot G, Meis JF, Rozalyani A, Sjam R, Widodo D, Djauzi S, Boekhout T. Candida nivariensis isolated from an Indonesian human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient suffering from oropharyngeal candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:388–391. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01660-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]