Abstract

Ruptured cerebral aneurysm is the most common cause of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Rarely cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) may present initially as acute SAH, and clinically mimics aneurysmal bleed. We report 2 cases of CVST who presented with severe headache associated with neck pain and focal seizures. Non-contrast brain CT showed SAH, involving the sulci of the convexity of hemisphere (cSAH) without involving the basal cisterns. Both patients received treatment with anticoagulants and improved. Awareness of this unusual presentation of CVST is important for early diagnosis and treatment. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the inclusion of vascular neuroimaging like MRI with venography or CT venography in the diagnostic workup of SAH, especially in a patient with strong clinical suspicion of CVST or in a patient where neuroimaging showed cSAH.

Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) suggests the presence of a vascular lesion, most commonly ruptured cerebral aneurysm. It is rare for SAH to be associated with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), and its location is usually different from the arterial aneurysms.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of SAH associated with CVST remains unknown; however, it is believed that it is probably induced by the rupture of dilated thin-walled cortical veins.1 Diagnosis of CVST associated with SAH usually depends on a high index of clinical suspicion combined with radiologic confirmation, so that appropriate treatment can be timely initiated. To date, 74 cases of CVST with radiological evidence of SAH, usually seen at the cerebral convexities, have been reported in the literature.3,4

We are reporting 2 cases of superior sagittal sinus (SSS) thrombosis that presented initially with SAH. Our objective in presenting these cases is to highlight the fact that CVST may present early as SAH, and vascular neuroimaging should be considered in selected cases, especially those cases, in which cerebral aneurysm is not detected and there is still a clinical suspicious of CVST. We also have addressed the non-aneurysmal convexity SAH (cSAH) which is being increasingly recognized with characteristic radiological pattern of venous SAH, as opposed to aneurysmal SAH. The use of systemic anticoagulation as an initial therapy of CVST, even in the presence of SAH is also briefly discussed.

Case Report

Patient 1

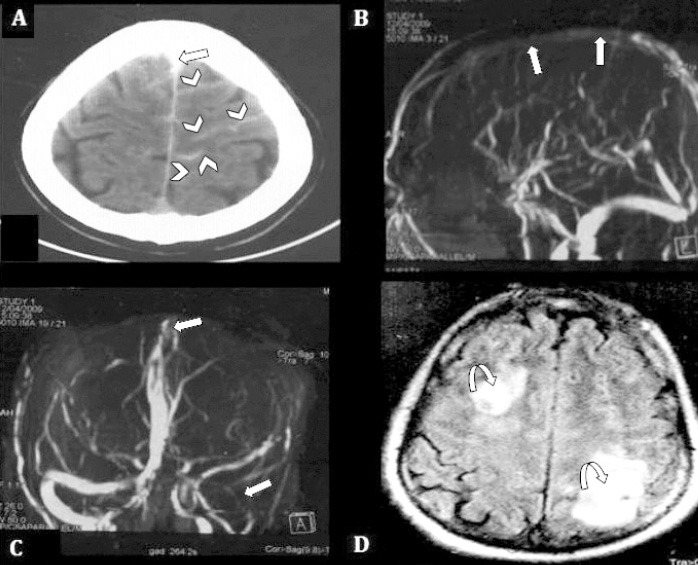

A 46-year-old male, with no known medical illness, presented to the emergency room (ER) with 3 days’ history of worsening severe generalized headache more over the frontal head region and neck pain. These symptoms were associated with right-sided weakness and focal seizures with secondary generalization. His general physical examination was unremarkable, while neurological examination showed normal higher mental function, bilateral mild papilledema, and mild right-sided weakness with extensor planter response. A non-contrast brain CT scan in the ER showed SAH in paramedian sulci bilaterally more over the left fronto-parietal region (Figure 1A). Neurosurgery attended the case in the ER and admitted him as a case of SAH for work up. The CT angiography was negative for aneurysmal bleed, and follow up CT brain showed venous infarct. The neurology service then took over the case and proceeded for MRI with venography (MRV), which showed obscuration of antero-superior portion of SSS and draining veins especially on right side (in lateral view, Figure 1B) as well as transverse and sigmoid sinuses in (maximum intensity projection [MIP] anterior oblique view, Figure 1C). Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images showed the areas of hyperintensity bilaterally in frontal and parietal regions consistent with venous infarcts (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Plain CT brain showing: A) SAH in paramedian sulci bilaterally over the left fronto-parietal region (cSAH), (arrow heads), and thrombosis of SSS (straight arrow). B) MRV 3D MIP image, anterior projection, demonstrate non-visualization of superior portion of SSS and draining veins. C) transverse and sigmoid sinus on the left side (straight arrows). D) FLAIR image, shows venous infarcts in frontal and parietal regions on both sides, (curved arrows). SAH - spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, cSAH - convexity SAH, SSS - superior sagittal sinus, MRV - magnetic resonance venography, MIP - maximum intensity projection

He was treated with body weight adjusted subcutaneous anticoagulation. Patient’s headache subsided within a week, and his neurological signs improved over 4 weeks. Etiological work up including thrombophilia testing was negative. He continued to take oral anticoagulation as an outpatient, which was continued for 6 months, and the International Normalization ratio (INR) was maintained between 2-3. At present he is seizure free, and is maintained on antiepileptic drugs.

Patient 2

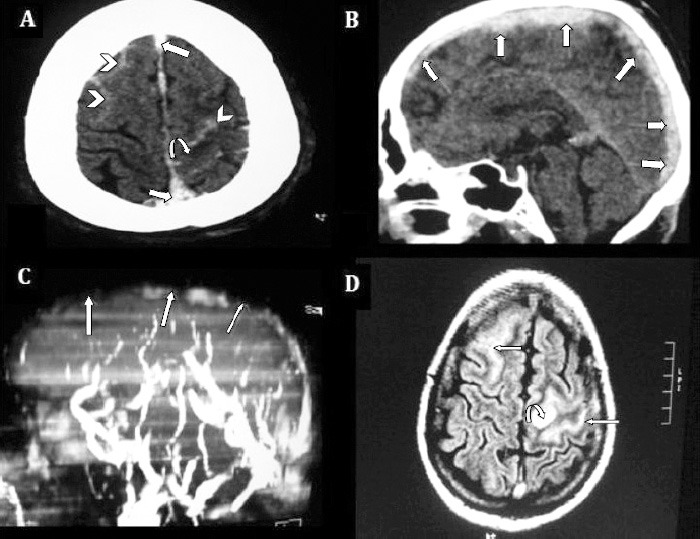

A 35-year-old male, previously with good health, admitted with a partial seizure preceded by sudden onset severe headache for 2 days. His physical examination was essentially normal except for bilateral mild papilledema and neck stiffness. Axial CT scan brain without contrast showed bilateral SAH, predominantly over the left fronto-parietal sulci, surrounded by venous infarct. Thrombus in SSS was evident (Figure 2A). Sagittal CT scan brain without contrast showed thrombosis of whole SSS (Figure 2B). The MRV showed SSS thrombosis with non-visualization of its tributaries (Figure 2C). Axial FLAIR images demonstrated hyperacute SAH as hyperintense curvilinear signal in bilateral frontal lobes. There were hyperintense signals in frontal cortex consistent with venous infarct (Figure 2D). Acute infarcts can also be reliably confirmed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences (not available for this case). This patient was started on dose-adjusted intravenous anticoagulation. Seizures were controlled with antiepileptic medication. A comprehensive hypercoagulability workup including levels of protein C and S, antithrombin III, and fibrinogen, anticardiolipin antibody, antiphospholipid antibody, and homocysteine level were all within normal limits. Patient’s symptoms improved over a week’s time during hospital stay. He continued to take oral anticoagulation as outpatient and INR was targeted between 2-3. He was lost to follow up after 4 months.

Figure 2.

Non-contrast enhanced axial CT brain showing: A) bilateral SAH (arrow heads), predominantly over left fronto-parietal sulci (cSAH) surrounded by hypodense venous infarct (curved arrow). B) Thrombosis of SSS also visualized in sagittal and axial cuts, (straight arrows). C) MRV 3D MIP image, left lateral projection, showed SSS thrombosis (straight arrows), with non visualization of its tributaries. D) FLAIR axial images demonstrate hyperacute SAH as hyperintense curvilinear signals in bilateral frontal lobes, (straight arrows), and hyperintense signals in frontal cortex consistent with venous infarct (curved arrow). SAH - spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, cSAH - convexity SAH, SSS - superior sagittal sinus, MRV - magnetic resonance venography, MIP - maximum intensity projection

Discussion

The diagnosis of CVST is typically made on the basis of radiological studies because the large spectrum of clinical manifestation makes clinical diagnosis of CVST difficult. Headache, focal seizures, focal motor or sensory deficits, and mental obtundation are the most commonly described symptoms.5

Both our cases presented with headache of sudden onset, neck stiffness, seizures, and imaging evidence of SAH, simulating a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. The correct diagnosis of CVST can be more difficult if it is associated with SAH, which is unusual with CVST.1,2 As with our first patient, who initially was admitted under neurosurgery as a potential case of aneurysmal bleed, initial imaging showed localized SAH without underlying parenchymal involvement.

The exact pathogenesis of SAH associated with CVST remains unknown. The most believable explanation is the extension of the venous hemorrhagic infarct into the subarachnoid spaces.1 In the absence of parenchymal sign of venous infarct (as in our patient one), SAH could be due to venous hypertension, secondary to back pressure due to blocked cerebral venous system that can lead to rupture of dilated, fragile, thin-walled, cortical veins resulting in bleeding into the subarachnoid space.1

An important practical issue needs to be addressed here. Clinical and imaging picture of patients with CVST and SAH can mimic aneurysmal SAH. An observation in the case reports and case series,3-7 regarding the distribution of SAH, is the difference in radiological findings between CVST and SAH from arterial origin due to aneurysmal bleed. Each has a characteristic pattern. Localized SAH in CVST is confined to parasagittal or dorsolateral cerebral convexity (cSAH), and sparing the basal cisterns. These findings should prompt the physician to look for non-aneurysmal causes of SAH by requesting additional vascular imaging of dural venous sinuses. Both of our cases showed cSAH in the brain imaging at presentation. Because of varied clinical spectrum, diagnosis of CVST is challenging in some clinical situations and is typically made by vascular imaging available at that time.

Digital subtraction angiography, an invasive procedure, was widely accepted in the past, as the gold standard for CVST diagnosis. In the present era, MRI combined with MRV is the single most sensitive and effective diagnostic method for CVST.8 In our cases, we used this investigative tool, because it is non-invasive, more convenient, and more reliable. The CT venography is considered a good alternative to MRI + MRV, and found to have both sensitivity and a specificity of 75-100% depending on the sinus and vein involved.8

The other differential diagnosis of cSAH is cerebral amyloid angiopathy, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, large-vessel stenotic atherosclerosis, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.6 There is a high incidence of spontaneous intracerebral bleeding within the venous infarct, and this concern created the controversy of using anticoagulation for many years. On other hand, withholding anticoagulation puts the patient at risk of developing ongoing occlusion of additional cortical veins and sinuses resulting in more extension of venous infarcts.9 Anticoagulation with heparin is generally considered the mainstay of treatment of CVST, supported by a few small clinical trials,9 and found to be beneficial and safe even in the presence of hemorrhagic infarction (Level of evidence B).10 Now, most clinical experts are agreed that full anticoagulation should be started in patients with CVST as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. We found anticoagulation safe and favorable with good clinical outcome in our 2 patients. Endovascular thrombolysis and decompressive hemicraniectomy are also available as more invasive treatment options for CVST. The first one is reserved for severe cases, not responding to full anticoagulation, while the other can be used as a life saving procedure in patients with large hemorrhagic venous infarct causing cerebral herniation.9

In conclusion, CVST is a potentially life threatening but treatable condition. Careful radiological as well as clinical analysis is important for the correct and early diagnosis of this condition. When SAH, is confined to cerebral convexity and sparing the basal cisterns, the strong and prompt suspicion of underlying CVST should be made to avoid any unnecessary delay in the management.

Footnotes

Disclosure.

Related articles.

Al-Hashel JY, John JK, Vembu P. Venous thrombosis of the brain. Retrospective review of 110 patiens in Kuwait. Neurosciences 2014; 19: 111-117.

Algahtani HA, Abdu AP, Shami AM, Hassan AE, Madkour MA, Al-Ghamdi, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in Saudi Arabia. Neurosciences 2011; 16: 329-334.

Kajtazi N, Zimmerman VA, Arulneyam JC, Al-Shami SY, Al-Senani FM. Cerebral venous thrombosis in saudi arabia. Clinical variables, response to treatment, and outcome. Neurosciences 2009; 14: 249-254.

References

- 1.Oppenheim C, Domigo V, Gauvrit JY, Lamy C, Mackowiak-Cordoliani MA, Pruvo JP, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage as the initial presentation of dural sinus thrombosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:614–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathon B, Ducros A, Bresson D, Herbrecht A, Mirone G, Houdart E, et al. Subarachnoid and intra-cerebral hemorrhage in young adults: rare and underdiagnosed. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2014;170:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashjazadeh N, Borhani Haghighi A, Poursadeghfard M, Azin H. Cerebral venous-sinus thrombosis: a case series analysis. Iran J Med Sci. 2011;36:178–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahin N, Solak A, Genc B, Bilgic N. Cerebral venous thrombosis as a rare cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage: case report and literature review. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:162–170. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khurram A, Kleinig T, Leyden J. Clinical associations and causes of convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2014;45:1151–1153. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panda S, Prashantha DK, Shankar SR, Nagaraja D. Localized convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage--a sign of early cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1249–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khandelwal N, Agarwal A, Kochhar R, Bapuraj JR, Singh P, Prabhakar S, et al. Comparison of CT venography with MR venography in cerebral sinovenous thrombosis. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1637–1643. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coutinho JM, Stam J. How to treat cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:877–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RI, Albers GW, Bush RL, Fagan SC, et al. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2011;42:227–276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]