Summary:

Outstanding results are difficult to achieve in postmastectomy reconstructions in obese ptotic patients. We describe an autologous single-stage reconstruction with free nipple grafts that is best suited for these difficult patients. This technique allows for delayed volume supplementation with implants or fat grafting but does not commit the patient to additional surgery. It avoids the common complications of immediate implant-based reconstructions. This technique is also an excellent option in patients with a known requirement for radiotherapy as it does not sacrifice a valuable autologous flap nor does it subject the patient to capsular contracture, infection, and extrusion. It also obviates the psychological trauma that many women suffer awaiting a reconstruction after radiotherapy. We believe it should be considered as a first-line reconstructive option.

Postmastectomy reconstruction in patients with macromastia, ptosis, and obesity is challenging.1–6 Although flap-based reconstructions may provide the best final aesthetic results, these patients often have additional comorbidities and risk factors that make these longer and more complex surgeries a less appealing option. Recently, a technique was described—“the Goldilocks mastectomy”—to provide patients with some degree of macromastia and ptosis, who would otherwise be poor candidates for immediate reconstruction with an implant or an autologous flap, a reconstructive option that utilized the dermis and adipose tissue from the mastectomy flap to reconstruct a breast mound.7 For the most part, this report described results that were somewhat of a compromise between a full reconstruction and no reconstruction at all. Patients were left with breast mounds that were smaller than would be typically provided by conventional reconstructions. In their original description, there was no attempt to salvage the nipple areolar complex (NAC), and additional surgery would be required for this as well. We believe that in the patient with sufficient ptosis and macromastia, the Goldilocks mastectomy can provide an immediate definitive reconstruction with free nipple grafts that may complete their reconstructive effort in a single stage. Here, we describe the first such case in the literature.

A 67-year-old woman had 10 cm of grade 3 ductal carcinoma in situ in her right breast. She had significant macromastia and ptosis (Fig. 1). She decided to proceed with bilateral mastectomy and wanted some form of reconstruction. She is a diabetic (HgbA1c 7.1) with a body mass index of 37 making her a high-risk candidate for any immediate implant or flap-based reconstruction. Given her obesity, macromastia, and ptosis, we felt that we could use the Goldilocks mastectomy to provide her with adequate breast volume to reconstruct her final breast mound in one stage. In addition, we planned on salvaging her left NAC as a free nipple graft and using the excess areolar skin to reconstruct the right NAC (proximity to cancer precluded saving this).

Fig. 1.

A 67-year-old woman with multicentric right breast ductal carcinoma in situ. She is obese with significant macromastia and ptosis. She is marked with a standard Wise pattern before surgery.

In the preoperative holding area, the patient was marked with standard bilateral Wise reduction patterns (Fig. 1). The right mastectomy was performed by incising the medial and lateral extensions to the inframammary fold and excising the NAC. Flaps were developed in standard fashion with care taken to completely remove the breast tissue but to preserve the subcutaneous layer. All of the skin within the mammoplasty markings was carefully deepithelialized. The inferior breast flap was separated from the superior flap. This allowed us to mold the inferior flap to recreate a breast mound. It was folded on itself transversely and then folded again vertically. A 2-0 polydioxanone suture (PDS) was used to create the mound securing dermis to dermis. This tissue was then shifted medially, so the bulk of the mound was centered over the meridian. This was also then secured to the pectoralis major muscle using additional PDS suture (Fig. 2). The superior mastectomy flap was then draped over the inferior breast mound much as we close an inferior pedicle breast reduction (Fig. 3). The vertical limbs are then brought together giving the reconstructed breast additional projection from the bulk supplied by the dermis and fat located between the limbs. The left prophylactic mastectomy and reconstruction were performed in exactly the same fashion. The left NAC is used as a free nipple graft to reconstruct the left breast, and the excess left areolar skin is used to reconstruct the right NAC. The final on-table result is a completed single-stage autologous reconstruction (Fig. 4).

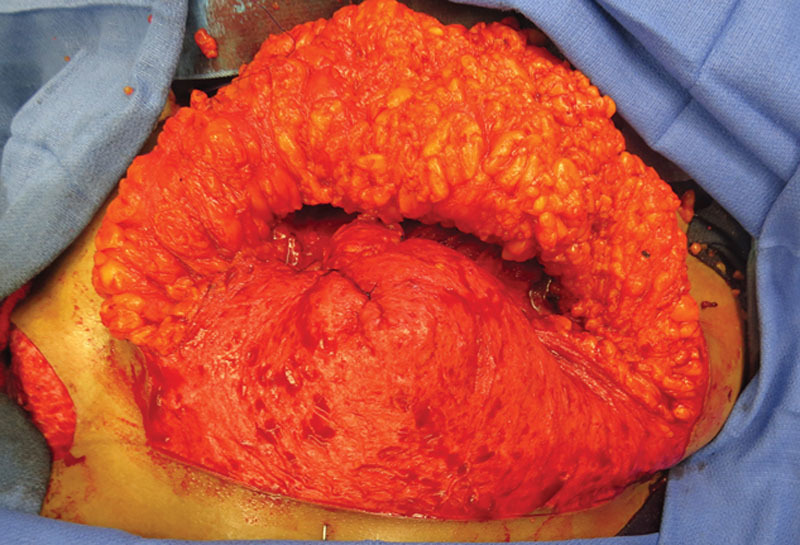

Fig. 2.

Reconstruction of the breast mound using the inferior mastectomy flap dermis and fat. It is folded on itself transversely and then vertically and centered over the meridian. Dermis is secured to dermis using 2-0 PDS and then sutured down to the pectoralis muscle.

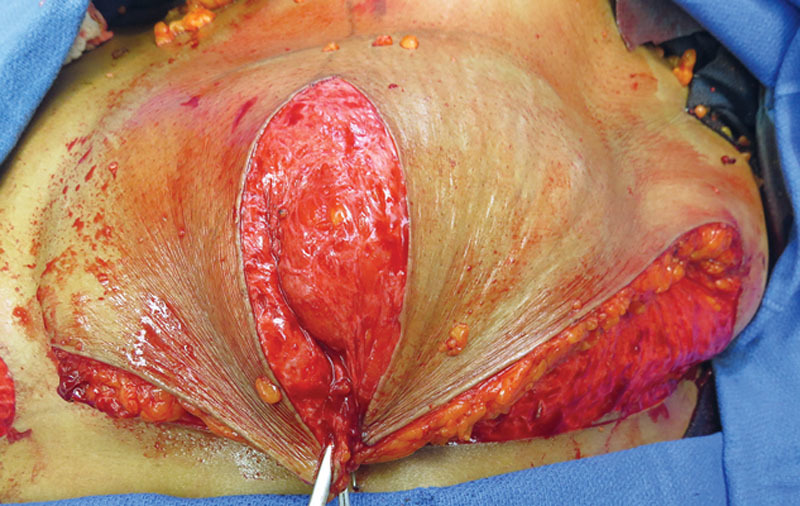

Fig. 3.

The superior mastectomy flap is brought down over the reconstructed breast mound to give the breast additional volume and projection. This closure is virtually identical to the standard closure of an inferior pedicle breast reduction.

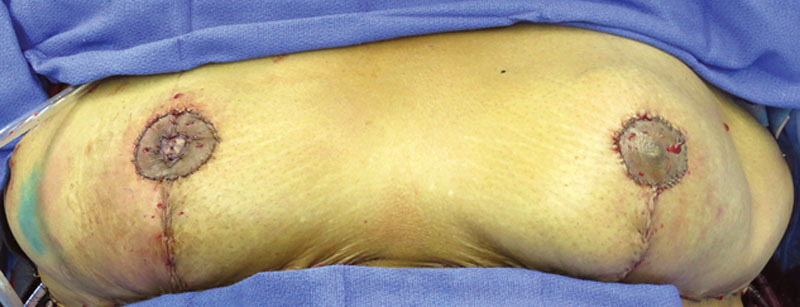

Fig. 4.

The final on-table result after free nipple grafting the left breast and reconstructing the right NAC with excess left areolar skin and a disk of right breast skin.

There is no doubt that in many patients with sufficient macromastia, ptosis, and a reasonable amount of adipose tissue, there exists sufficient volume to reconstruct breast mounds in a single stage. These breast mounds are aesthetic in appearance as the skin envelope has been retailored using a Wise pattern, and the excess dermis and fat are sculpted into a conical shape and centered over the meridian competing very favorably with traditional reconstructions. We also feel that NAC reconstruction with free nipple grafts should be a standard practice unless the patient refuses or oncological considerations preclude this. This case report describes an immediate, definitive postmastectomy reconstruction in a single operation that routinely takes multiple surgeries to complete using other techniques. Many of these patients are not interested in such a long reconstructive process or are at high risk for multiple general anesthetics.

There are many patients who demand a completely autologous reconstruction and are not good candidates for bilateral abdominal-based autologous flaps. The surgery described here with the option of delayed fat grafting can provide this patient population a completely autologous option with significantly less operative time, fewer complications, no donor site scars, and without the need for microvascular surgery expertise.

This strategy described here coupled with a second-stage definitive implant may also become the preferred standard practice in many patients with macromastia, ptosis, and obesity when compared with the traditional expander-based reconstructions followed by definitive implants. This approach avoids the complications of immediate implant-based reconstructions, namely expander infection and extrusion, and probably minimizes the chances of capsular contracture as the definitive implant can be placed in a sterile, blood-free environment avoiding the immediate postmastectomy milieu. This patient population is at highest risk for infection and implant extrusion, which can be minimized with this strategy.8

Finally, this strategy may play an important role in this population of patients who require postmastectomy radiotherapy. Postmastectomy reconstruction in the face of a known requirement for radiotherapy is a challenging and controversial area often with poor and unpredictable results, frequently requiring flap surgery.9–11 We feel that patients who undergo our modified Goldilocks surgery may tolerate radiotherapy in a manner similar to that of breast conservation patients, with minimal impact on the shape and suppleness of the reconstruction. The option of delayed fat grafting can provide additional volume and enhance mastectomy flap health after radiotherapy is completed. We feel that this is a promising technique that requires careful study and follow-up to determine long-term results in comparison with our current standard practices.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albornoz CR, Cordeiro PG, Farias-Eisner G, et al. Diminishing relative contraindications for immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:363e–369e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen KT, Hanwright PJ, Smetona JT, et al. Body mass index as a continuous predictor of outcomes after expander-implant breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73:19–24. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318276d91d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer JP, Wes AM, Kanchwala S, Kovach SJ. Effect of BMI on modality-specific outcomes in immediate breast reconstruction (IBR)—a propensity-matched analysis using the 2005–2011 ACS-NSQIP. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48:297–304. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2013.877915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson JA, Kovach SJ, Serletti JM, et al. Impact of obesity on outcomes in breast reconstruction: analysis of 15,937 patients from the ACS-NSQIP datasets. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanwright PJ, Davila AA, Hirsch EM, et al. The differential effect of BMI on prosthetic versus autogenous breast reconstruction: a multivariate analysis of 12,986 patients. Breast. 2013;22:938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies K, Allan L, Roblin P, et al. Factors affecting post-operative complications following skin sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction. Breast. 2011;20:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson H, Ma G. The Goldilocks mastectomy. Int J Surg. 2012;10:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer JP, Wes AM, Tuggle CT, 3rd, et al. Risk analysis of early implant loss after immediate breast reconstruction: a review of 14,585 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:983–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Sabawi B, Sosin M, Carey JN, et al. Breast reconstruction and adjuvant therapy: a systematic review of surgical outcomes. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:458–464. doi: 10.1002/jso.24028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaverien MV, Macmillan RD, McCulley SJ. Is immediate autologous breast reconstruction with postoperative radiotherapy good practice?: a systematic review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:1637–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordeiro PG, Albornoz CR, McCormick B, et al. What is the optimum timing of postmastectomy radiotherapy in two-stage prosthetic reconstruction: radiation to the tissue expander or permanent implant? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:1509–1517. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]