Abstract

Background:

Differentiating between superficial and deep-dermal (DD) burns remains challenging. Superficial-dermal burns heal with conservative treatment; DD burns often require excision and skin grafting. Decision of surgical treatment is often delayed until burn depth is definitively identified. This study’s aim is to assess the ability of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) to differentiate burn depth.

Methods:

Thermal injury of graded severity was generated on the dorsum of hairless mice with a heated brass rod. Perfusion and oxygenation parameters of injured skin were measured with HSI, a noninvasive method of diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, at 2 minutes, 1, 24, 48 and 72 hours after wounding. Burn depth was measured histologically in 12 mice from each burn group (n = 72) at 72 hours.

Results:

Three levels of burn depth were verified histologically: intermediate-dermal (ID), DD, and full-thickness. At 24 hours post injury, total hemoglobin (tHb) increased by 67% and 16% in ID and DD burns, respectively. In contrast, tHb decreased to 36% of its original levels in full-thickness burns. Differences in deoxygenated and tHb among all groups were significant (P < 0.001) at 24 hours post injury.

Conclusions:

HSI was able to differentiate among 3 discrete levels of burn injury. This is likely because of its correlation with skin perfusion: superficial burn injury causes an inflammatory response and increased perfusion to the burn site, whereas deeper burns destroy the dermal microvasculature and a decrease in perfusion follows. This study supports further investigation of HSI in early burn depth assessment.

Early excision and skin grafting of full-thickness (FT) and deep-dermal (DD) burns have been shown to be therapeutically and financially advantageous, with shorter healing time, fewer infections, better functional and aesthetic results, and reduced hospital stay.1–6 DD burns are best managed by excision and skin grafting,7–11 but early differentiation of superficial-dermal versus DD burns presents a diagnostic challenge. Differentiation between superficial burns that spontaneously heal and those that require excision is still inconsistent, with only 50–75% accuracy in early clinical assessments.4,12–16

Current standard of care involves waiting for clinical signs of diminished sensation, leathery feel, and pale color as the telltale signs of burn depth progression, indicating necessity of excision. Clinical overestimation of burn depth results in unnecessary surgery, whereas underestimation results in delayed surgery and prolonged hospital stays. As such, early and reliable differentiation between superficial-dermal and DD burns at early time points remains a top priority in burn research.4,7,8,12–19

Various modalities to distinguish burn depth at early time points have been investigated including thermography,20,21 ultrasonography,22 nuclear magnetic resonance,23 laser Doppler,12–15,18,19,24–28 and confocal microscopy,29 among others.4,8 Histology remains the gold standard; however, because of potential sampling error, processing delays, and its inherent invasiveness, it has little application in clinical practice.

A promising parameter for burn depth assessment has been its correlation with skin perfusion. Superficial burn injury causes an inflammatory response and increased perfusion to the burn site.30 Deeper burns destroy more of the dermal microvasculature, and thus, the postinjury perfusion increase is not as robust or is instead, decreased.31,32 Near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy and laser Doppler imaging (LDI) are two experimental techniques that rely on this principle. Some promising reports regarding burn depth estimation are available using NIR spectroscopy,31–33 and LDI has shown great promise in studies.13–15,19,24–28

In our laboratory, we have studied hyperspectral imaging (HSI) as an alternative method of noninvasive diagnosis of tissue perfusion34,35 OxyVu2 (HyperMed, Greenwich, Conn.) is an FDA-approved, commercially available imager in the visible spectrum HSI (vsHSI), which utilizes wide-field diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. vsHSI has been used by our group to quantify postradiation dermal perfusion changes in an animal model34,35 and is currently being used to predict healing potential of diabetic foot ulcers.36

In this report, we characterize the dermal perfusion and oxygenation profiles of 3 burn depths during the first 3 days post injury: intermediate-dermal (ID), DD, and FT injuries. Second, we assess whether vsHSI could differentiate the burn depth groups based on any of the parameters it quantified: oxygenated hemoglobin (oxyHb), deoxygenated hemoglobin (deoxyHb), total hemoglobin (tHb), or oxygen saturation (StO2).

METHODS

Animals and Thermal Burn Procedure

All handling of and procedures performed with animals was done in accordance with a protocol (UMass IACUC Protocol #A2454) approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Seventy-two immune-competent, adult 6–8 weeks old male mice (SKH-1 Elite, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) weighing 28–32 g were used. Anesthesia for thermal burn procedure and imaging was performed with a mixture of ketamine (55 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Tattoo marks were placed on the dorsum of the mice to act as fiducial marks. After anesthesia, the dorsal skin was distracted from the body, and a 1.5-cm diameter brass rod of 82 g heated to 50°C (n = 12), 55°C (n = 12), 60°C (n = 12), 70°C (n = 12), 80°C (n = 12), or 90°C (n = 12) was applied to the dorsum of the anesthetized mice (gravity only) for 10 seconds creating thermal injury of graded severity. Animals received subcutaneous, slow release buprenorphine (0.2 mg/kg) and intraperitoneal 1 mL of normal saline after the burn procedure. Mice randomly were killed at 72 hours after burn injury (n = 72), and biopsy samples were taken for histological analysis.

Histological Burn Depth Analysis

Punch skin biopsies were taken from the center of burns at 72 hours post injury to evaluate burn progression during the first 3 days post injury.37,38 Biopsies were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Ten-μm- sections were stained with Masson’s Trichrome, a stain favorable in partial burns because of its magenta-red coloring of denatured collagen, indicative of the extent of partial burn, whereas rapid FT burns are characterized by a glass-like fixed appearance.39 Images were taken with an Olympus microscope at 10× magnification. Burn depth was measured with a linear tool of Image J from every picture at 3 places in each image: left, center, and right. Percent burn depth was defined as depth of denatured collagen divided by depth to Panniculus carnosus muscle × 100. Averages were taken of all the depths measured for each temperature of burn.

Evaluation of Cutaneous Perfusion and Oxygenation with vsHSI

Perfusion and oxygenation parameters of the injured skin were measured with vsHSI, a noninvasive method of wide-field, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy at baseline before the burn and at 2 minutes, 1, 24, 48, and 72 hours after burn injury. Observers were blinded to temperature group.

The OxyVu2 device utilizes a spectral separator to vary the wavelength of visible light entering a digital camera and provides a diffuse reflectance spectrum for every pixel. Using proprietary algorithms, these spectra are then compared with standard transmission solutions to calculate the concentration of oxyHb and deoxyHb in each pixel, from which spatial maps of these parameters are constructed and used for quantification of cutaneous perfusion and oxygenation. These maps were analyzed with MATLAB R2010b (Mathworks Inc., Natick, Mass.). Mean values of oxyHb and deoxyHb were calculated for a 79-pixel area (1 cm diameter) corresponding to the burned skin. This 79-pixel area was determined precisely over time with reference to the fiducial tattoo marks that were placed before burn injury. OxyHb and deoxyHb values were summed to yield total tissue hemoglobin (tHb), which represents total blood volume and thus total perfusion in the area of skin examined. Tissue StO2 was calculated as oxyHb divided by tHb.

Postburn oxyHb, deoxyHb, tHb, and StO2 values are expressed as relative to preburn values within the same area of skin to account for oxygenation differences between animals at baseline.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted on all of the measures of hemoglobin concentration: oxyHb, deoxyHb, tHb, and StO2 at the burn site at each time point, including 2 minutes, 1, 24, 48, and 72 hours after the induced burn. We used a series of Kruskal–Wallis tests to determine whether there are any significant differences in hemoglobin concentration measures by the class of burn. A separate test for each measure of hemoglobin concentration at each separate time measure was performed. Nonparametric post-hoc Wilcoxon rank sum tests comparing whether a hemoglobin measure was different between two specific classes of burn at the same time point was applied. Post-hoc tests were only conducted when the omnibus Kruskal–Wallis test found a significant difference in hemoglobin measures by the 3 classes of burn: ID, DD, and FT. All statistical tests were performed using Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, Tex.). All averages are reported with ±1 SD, and results were considered significant when P value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Histological Assessment

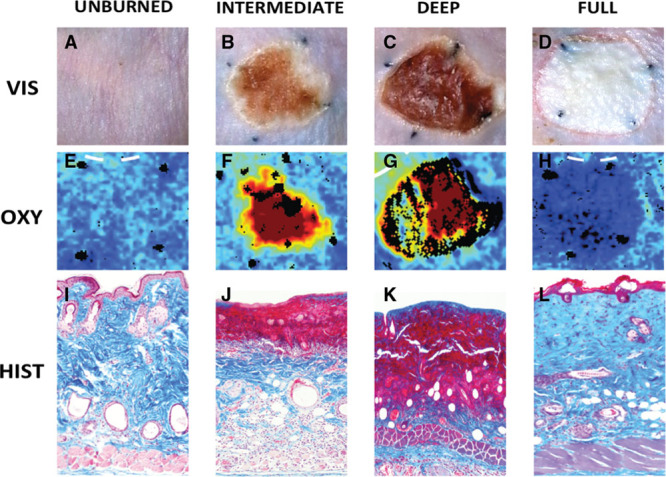

Three discrete levels of burn depth were identified histologically. Fifty and 55ºC groups produced no injury. The 60ºC group resulted in 58% (±18) of dermal damage, which was classified as ID burn. The 70ºC group resulted in 80% (±14) of dermal damage, which was classified as DD burn. Both 80 and 90ºC groups resulted in FT injury 95% (±13%) and 99% (± 2%), respectively (Fig. 1). Analysis of variance of all groups (no injury, ID, DD, and FT) demonstrated significant differences between burn levels (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Macroscopic, histological, and vsHSI comparisons at 3 days post burn. A, E, I, unburned skin; B, F, J, ID burn; C, G, K, DD burn; and D, H, L, full-thickness burn. A–D show gross view, E–H show vsHSI (OxyHb parameter), I–L show histology 10× magnification and stained with Masson’s trichrome.

Evaluation of Cutaneous Perfusion and Oxygenation with vsHSI

Total Hemoglobin

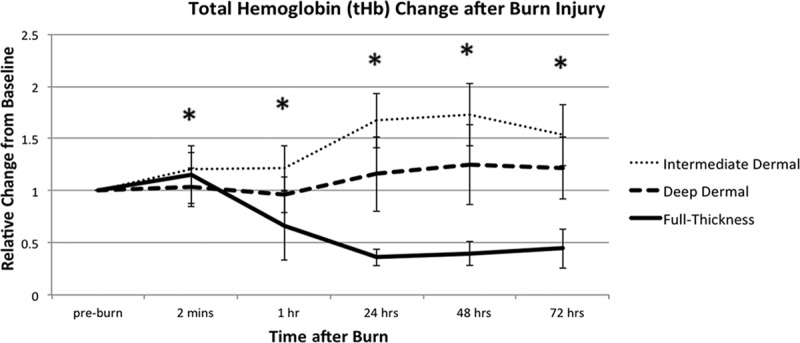

The ID burn group exhibited a rise in tHb beginning at 2 minutes post injury, peaked at 48 hours with a 72% (±30) increase over baseline and continued to be elevated until the end of the experiment at 72 hours with a 53% (±29) increase over baseline. The DD group also exhibited an increase in tHb over baseline levels, though to a lesser extent than the ID group, with a tHb peak at 48 hours of 25% (±38) increase over baseline levels and a 22% (±30) increase at 72 hours. FT injury had a reduction in tHb beginning at 1 hour to 67% (±33) of baseline levels and reached the lowest point at 24 hours at 36% (±8) of baseline levels; at 72 hours, tHb levels were 44% (±17) of original levels (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total hemoglobin (tHb) variations in 3 depths of burn. tHb is relative to its preburn baseline for the 3 depths of burn, measured during the first 72 hours post injury. All values are expressed as mean ± SD of the mean. Statistical significance of P value of less than 0.05 between ID and DD burns is indicated with an asterisk (*).

Oxygenated and Deoxygenated Hemoglobin

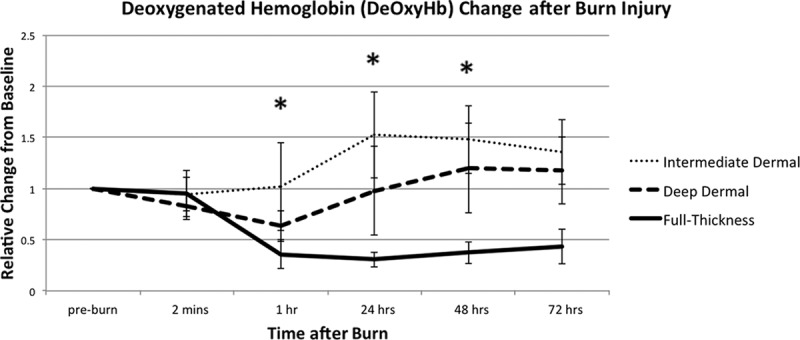

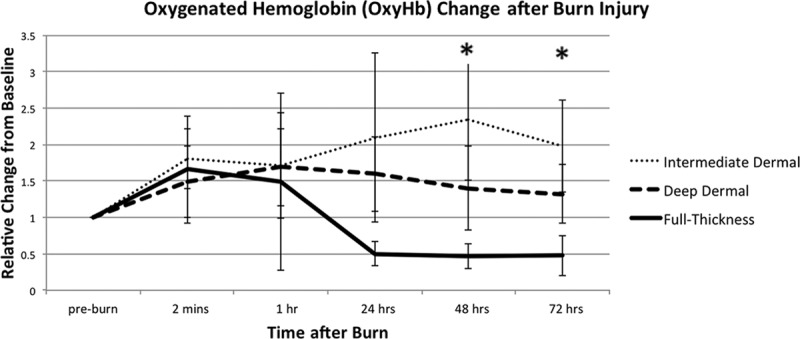

Figure 3 shows the changes in deoxyHb and Figure 4, changes in oxyHb, of each burn depth, over 72 hours post injury. The ID burn group had the greatest rise in both oxyHb and deoxyHb. ID group’s oxyHb peaked at 48 hours at 134% (±82) increase over baseline, and its deoxyHb peaked at 24 hours with 52% (±42) over baseline.

Fig. 3.

Deoxygenated hemoglobin (deOxyHb) variations in 3 depths of burn. DeOxyHb is relative to its preburn baseline for the 3 depths of burn, measured during the first 72 hours post injury. All values are expressed as mean ± SD of the mean. Statistical significance of P value of less than 0.05 between ID and DD burns is indicated with an asterisk (*).

Fig. 4.

Oxygenated hemoglobin (OxyHb) variations in 3 depths of burn. OxyHb is relative to its preburn baseline for the 3 depths of burn, measured during the first 72 hours post injury. All values are expressed as mean ± SD of the mean. Statistical significance of P value of less than 0.05 between ID and DD burns is indicated with an asterisk (*).

DD burn group had a peak of oxyHb at 1 hour at 69% (±53) over baseline, and then it trended down, with 32% (±41) over original levels at 72 hours. DD’s deoxyHb initially decreased after injury, at 63% (±15) of baseline levels, at 1 hour. Then, it increased to preburn levels by 24 hours and to 1.20 above baseline levels at 48 and 72 hours.

FT burn group had an increase in oxyHb of 49% (±22) at 1 hour, followed by a decrease of 48–50% of baseline levels at 24, 48, and 72 hours. The deoxyHb in the FT group decreased at 1 hour to 36% (±14) and at 24 hours to 31% (±7) of baseline levels; at 48 and 72 hours, deoxyHb recovered slightly to 38% (±11) and 44% (±17) of baseline levels, respectively.

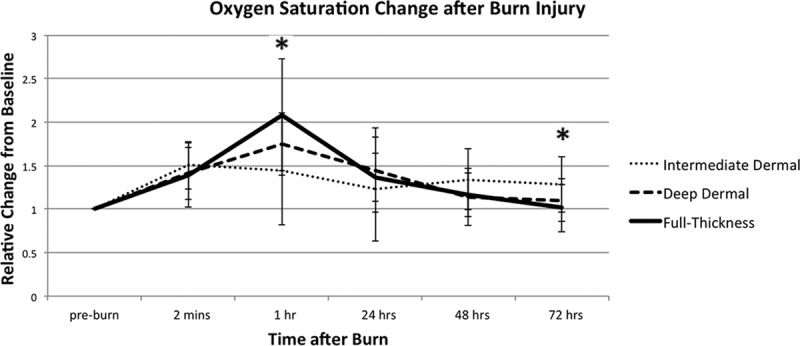

Oxygen Saturation

Figure 5 depicts saturation changes in the 3 burn depth groups post injury. At 1 hour post injury, FT group had the greatest increase in saturation, 108% (±64) increase over baseline. DD exhibited a 74% (±36) increase and ID a 44% (±62) increase over baseline.

Fig. 5.

Oxygen saturation (StO2) variations in 3 depths of burn. StO2 is relative to its preburn baseline for the 3 depths of burn, measured during the first 72 hours post injury. All values are expressed as mean ± SD of the mean. Statistical significance of P value of less than 0.05 between ID and DD burns is indicated with an asterisk (*).

Assessing Early Differences between Burn Groups

Intermediate Dermal versus Deep Dermal

ID versus DD perfusion measurements were statistically different at 1 hour for the following parameters: deoxyHb (P < 0.001), tHb (P < 0.01), and StO2 (P < 0.05). oxyHb did not differentiate ID versus DD burns at 1 or 24 hours, P = 0.95 and P = 0.41, respectively.

Deep Dermal versus Full-Thickness

DD versus FT injury perfusion measurements were statistically different at 1 hour for the following parameters: deoxyHb (P < 0.001), tHb (P < 0.001), and StO2 (P < 0.05). oxyHb was not significant at 1 hour (P = 0.09). At 24-, 48-, and 72-hour time points, all parameters remained statistically significant, with the exception of saturation.

Intermediate Dermal versus Full-Thickness

ID versus FT burns were statistically different for the following parameters at 1 hour: deoxyHb (P < 0.001), tHb (P < 0.001), and StO2 (P < 0.001). OxyHb was not statistically significant at 1 hour, with P = 0.14. As for all other comparisons, StO2 was only significant at 1 and 72 hours, whereas all other parameters remained significant for the rest of the time points: 24, 48, and 72 hours.

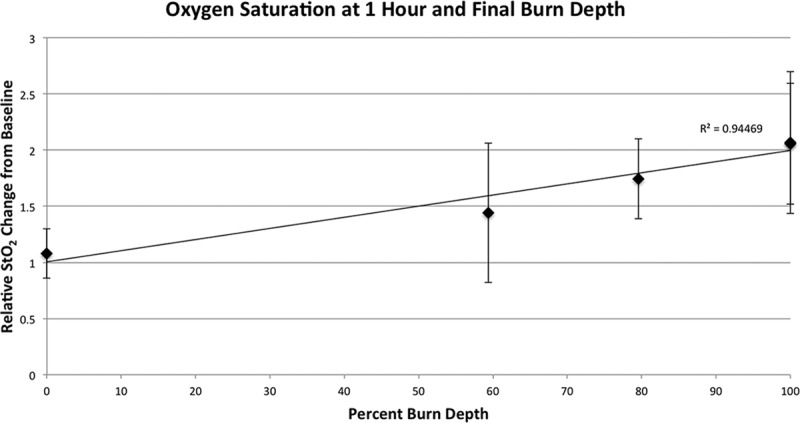

Early Prediction of Burn Depth

When 1-hour tissue StO2 was related to final 72-hour burn depth, a regression analysis demonstrated a strong linear correlation between StO2 and burn depth (R2 = 0.94; P < 0.001). This suggested that early 1-hour tissue StO2 may be related to final burn depth 3 days later (Fig. 6). None of the other parameters demonstrated a correlated pattern at 1 hour.

Fig. 6.

Final burn depth compared with oxygen saturation (StO2). Final burn depth at 72 hours post injury plotted against relative StO2 change at 1 hour demonstrated a strong linear correlation (R2 = 0.94; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was two-fold: to characterize dermal perfusion and oxygenation in 3 sequential depths of burn over the dynamic, 3-day period after burn injury and to assess whether vsHSI could differentiate depths of injury, based on any of the parameters it quantifies: oxyHb, deoxyHb, tHb, or StO2.

Several experimental approaches have used tissue perfusion for burn depth estimation including LDI,12–15,18,19,24–28 indocyanine green videoangiography,40,41 transcutaneous capillary videomicroscopy,42 reflectance-mode confocal microscopy,29 spatial frequency domain imaging,43,44 and NIR spectroscopy.31–33 These techniques share a common premise; they assess dermal perfusion, which is then used as an analog for tissue viability. Of the aforementioned methods of optical perfusion quantification,45 the technique that is most similar to our experimental methods is NIR spectroscopy, for both NIR and vsHSI quantify oxyHb and deoxyHb.31–33

OxyVu2, the vsHSI device used in our study, differs from NIR spectroscopy in that it uses wavelengths of visible light, specifically 500–660 nm, rather than the NIR spectrum, 700–1000 nm. NIR light penetrates deeper into soft tissues, 1–2 cm,33 whereas the visible spectrum has greater absorption by chromophores in the skin and thus does not penetrate as far, specifically 1–2 mm.46,47 One to two millimeters is also the depth of penetration of LDI48 and a good approximation of the human dermis, most of which is 1–2 mm thick, with the total range being from 0.5 mm on eyelids to 6 mm between shoulder blades.49 Cross et al32 demonstrated that superficial and FT burns could be differentiated with NIR spectroscopy in human subjects; however, intermediate and deep partial burns have not yet been differentiated. As the difference between superficial-dermal and DD burns is in the extent of dermal damage, we hypothesized that a more robust difference in perfusion between this “gray-zone” of injury may be apparent using the visible rather than the NIR spectrum.

Perfusion Profiles

ID burn group exhibited the greatest increase in oxyHb, deoxyHb, and tHb throughout the study, followed by DD burns, which also demonstrated an increase in perfusion parameters, albeit to a lesser degree. FT burns exhibited a decrease in perfusion parameters (Figs. 2, 3, 4). As part of the dermis is destroyed, an inflammatory reaction takes place, which signals for increased perfusion to the burn site30 The more superficial the burn, the more of the dermal microvasculature is intact, and thus, an increased demand in perfusion can be met with an increased supply and delivery to tissues. In deeper burns, where more of the dermal microvasculature is destroyed, perfusion is compromised. Similar trends in postburn perfusion were also observed by another group when using NIR technology.31,32

A surprising finding in FT injury was increased oxyHb to 49% over baseline at 1 hour, before its drop at 24 hours. Possible explanations include the formation of traumatic microhemorrhages because of extreme thermal damage, poor oxygen extraction by the severely injured tissue, or a combination of both.50

Oxygenation Profiles

An interesting finding that did not follow prior NIR results31,32 was tissue oxygenation at 1 hour post injury. FT burns exhibited the greatest increase in StO2, 108% increase over baseline; DD burns exhibited a 74% increase; and ID burns, the smallest increase over baseline: 44% (Fig. 5). This observation may be because of acute changes in vascular permeability after injury with vessels sustaining more damage and exhibiting greater vascular leak.

In contrast to our findings, NIR spectroscopy work demonstrated the greatest decrease of StO2 in FT injury and the smallest decrease in superficial burn.31 However, as NIR penetrates deeper than vsHSI, 2 cm versus 2 mm, respectively, it is likely that these techniques capture different vascular networks and thus a different response to healing. This is supported by a finding that saturation trends differed between NIR and vsHSI when monitoring the same amputation wounds with both techniques: NIR exhibited a decrease in saturation over several days (80–68%) and vsHSI, an increase (62–70%), meeting at a similar saturation.51

Differentiating Burn Depth

We found the most reliable differentiators of burn depth at the majority of time points were tHb and deoxyHb. OxyHb alone had wide variability and did not reliably differentiate burn depths until 48 hours. StO2 seemed statistically significant at 1 hour between all the burn depths, but this difference disappeared at 24 and 48 hours suggesting that the StO2 change is transient. We believe these changes in StO2 to be the most powerful predictor of burn depth as StO2 seems to be highly correlated to final burn depth and may be an early predictive indicator of burn severity. A reliable predictive indicator of final burn depth has not been previously demonstrated and could be a valuable tool for staging early excisions and application of mitigating therapies.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although this mouse model shows promising results of vsHSI utility in burn depth differentiation, further translational study using a porcine model may help validate our findings because the dermal thickness and burn injury are more similar to human skin.52,53 In addition, clinical validation of vsHSI is needed. Questions of debris, blisters, ointments, and their effects on vsHSI readings have yet to be elucidated, as these have confounded LDI and indocyanine green videoangiography measurements in burn depth assessments.54–56

Comparisons of vsHSI and LDI in burn depth differentiation are also needed, as LDI has proven to be an excellent aid in burn depth determination and is arguably the best current burn depth predictor, besides histology. Although LDI and vsHSI techniques examine differing parameters of perfusion, flow, and hemoglobin concentration, their penetrating depth is similar at 1–2 mm,48 which gives promise to vsHSI in its burn differentiating utility. An asset that vsHSI brings is the ability to quantify the oxygenation status of tissue. This may help discern thrombosis versus arterial spasm or detect early metabolic changes of dying tissues. Furthermore, when compared with NIR, the property of vsHSI to remain relatively superficial in perfusion assessment may be helpful in estimating the desired depth of tangential excisions.57

Footnotes

Presented at, in part, the 2014 New England Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, Sebasco, Maine, June 7, 2014.

Disclosures: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Feller I, Tholen D, Cornell RG. Improvements in burn care, 1965 to 1979. JAMA. 1980;244:2074–2078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herndon DN, Barrow RE, Rutan RL, et al. A comparison of conservative versus early excision. Therapies in severely burned patients. Ann Surg. 1989;209:547–52; discussion 552. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198905000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong YS, Samuel M, Song C. Meta-analysis of early excision of burns. Burns. 2006;32:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heimbach D, Engrav L, Grube B, et al. Burn depth: a review. World J Surg. 1992;16:10–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02067108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasanna M, Singh K, Kumar P. Early tangential excision and skin grafting as a routine method of burn wound management: an experience from a developing country. Burns. 1994;20:446–450. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke JF, Quinby WC, Jr, Bondoc CC. Primary excision and prompt grafting as routine therapy for the treatment of thermal burns in children. Surg Clin North Am. 1976;56:477–494. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40890-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson RM, Richard R. Partial-thickness burns: identification and management. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2003;16:178–187; quiz 188. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaskille AD, Shupp JW, Jordan MH, et al. Critical review of burn depth assessment techniques: part I. Historical review. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30:937–947. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181c07f21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray DT, Pine RW, Harnar TJ, et al. Early surgical excision versus conventional therapy in patients with 20 to 40 percent burns. A comparative study. Am J Surg. 1982;144:76–80. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjöberg F, Danielsson P, Andersson L, et al. Utility of an intervention scoring system in documenting effects of changes in burn treatment. Burns. 2000;26:553–559. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engrav LH, Heimbach DM, Reus JL, et al. Early excision and grafting vs. nonoperative treatment of burns of indeterminant depth: a randomized prospective study. J Trauma. 1983;23:1001–1004. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsbjörn B, Micheels J, Sørensen B. Laser Doppler flowmetry measurements of superficial dermal, deep dermal and subdermal burns. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;18:75–79. doi: 10.3109/02844318409057406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niazi ZB, Essex TJ, Papini R, et al. New laser Doppler scanner, a valuable adjunct in burn depth assessment. Burns. 1993;19:485–489. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(93)90004-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pape SA, Skouras CA, Byrne PO. An audit of the use of laser Doppler imaging (LDI) in the assessment of burns of intermediate depth. Burns. 2001;27:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Droog EJ, Steenbergen W, Sjöberg F. Measurement of depth of burns by laser Doppler perfusion imaging. Burns. 2001;27:561–568. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heimbach DM, Afromowitz MA, Engrav LH, et al. Burn depth estimation–man or machine. J Trauma. 1984;24:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monstrey S, Hoeksema H, Verbelen J, et al. Assessment of burn depth and burn wound healing potential. Burns. 2008;34:761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park YS, Choi YH, Lee HS, et al. The impact of laser Doppler imaging on the early decision-making process for surgical intervention in adults with indeterminate burns. Burns. 2013;39:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeksema H, Van de Sijpe K, Tondu T, et al. Accuracy of early burn depth assessment by laser Doppler imaging on different days post burn. Burns. 2009;35:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mladick R, Georgiade N, Thorne F. A clinical evaluation of the use of thermography in determining degree of burn injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;38:512–518. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196638060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prindeze NJ, Fathi P, Mino MJ, et al. Examination of the early diagnostic applicability of active dynamic thermography for burn wound depth assessment and concept analysis. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36:626–35. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iraniha S, Cinat ME, VanderKam VM, et al. Determination of burn depth with noncontact ultrasonography. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2000;21:333–338. doi: 10.1067/mbc.2000.106391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koruda MJ, Zimbler A, Settle RG, et al. Assessing burn wound depth using in vitro nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). J Surg Res. 1986;40:475–481. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(86)90218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kloppenberg FW, Beerthuizen GI, ten Duis HJ. Perfusion of burn wounds assessed by laser Doppler imaging is related to burn depth and healing time. Burns. 2001;27:359–363. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riordan CL, McDonough M, Davidson JM, et al. Noncontact laser Doppler imaging in burn depth analysis of the extremities. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:177–186. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000075966.50533.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atiles L, Mileski W, Spann K, et al. Early assessment of pediatric burn wounds by laser Doppler flowmetry. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995;16:596–601. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atiles L, Mileski W, Purdue G, et al. Laser Doppler flowmetry in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995;16:388–393. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pape SA, Baker RD, Wilson D, et al. Burn wound healing time assessed by laser Doppler imaging (LDI). Part 1: derivation of a dedicated colour code for image interpretation. Burns. 2012;38:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altintas MA, Altintas AA, Knobloch K, et al. Differentiation of superficial-partial vs. deep-partial thickness burn injuries in vivo by confocal-laser-scanning microscopy. Burns. 2009;35:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotran RS, Remensnyder JP. The structural basis of increased vascular permeabiligy after graded thermal injury—light and electron microscopic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;150:495–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb14702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sowa MG, Leonardi L, Payette JR, et al. Near infrared spectroscopic assessment of hemodynamic changes in the early post-burn period. Burns. 2001;27:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cross KM, Leonardi L, Payette JR, et al. Clinical utilization of near-infrared spectroscopy devices for burn depth assessment. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:332–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seki T, Fujioka M, Fukushima H, et al. Regional tissue oxygen saturation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy to assess the depth of burn injuries. Int J Burns Trauma. 2014;4:40–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chin MS, Freniere BB, Bonney CF, et al. Skin perfusion and oxygenation changes in radiation fibrosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:707–716. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182818b94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chin MS, Freniere BB, Lo YC, et al. Hyperspectral imaging for early detection of oxygenation and perfusion changes in irradiated skin. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17:026010. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.2.026010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yudovsky D, Nouvong A, Pilon L. Hyperspectral imaging in diabetic foot wound care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4:1099–1113. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson DM. [The diagnosis of the depth of burning]. Br J Surg. 1953;40:588–596. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004016413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tobalem M, Harder Y, Tschanz E, et al. First-aid with warm water delays burn progression and increases skin survival. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chvapil M, Speer DP, Owen JA, et al. Identification of the depth of burn injury by collagen stainability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:438–441. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198403000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, et al. Indocyanine green video angiographies help to identify burns requiring operation. Burns. 2003;29:785–791. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Still JM, Law EJ, Klavuhn KG, et al. Diagnosis of burn depth using laser-induced indocyanine green fluorescence: a preliminary clinical trial. Burns. 2001;27:364–371. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGill DJ, Sørensen K, MacKay IR, et al. Assessment of burn depth: a prospective, blinded comparison of laser Doppler imaging and videomicroscopy. Burns. 2007;33:833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen JQ, Crouzet C, Mai T, et al. Spatial frequency domain imaging of burn wounds in a preclinical model of graded burn severity. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:66010. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.6.066010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponticorvo A, Burmeister DM, Yang B, et al. Quantitative assessment of graded burn wounds in a porcine model using spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI) and laser speckle imaging (LSI). Biomed Opt Express. 2014;5:3467–3481. doi: 10.1364/BOE.5.003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaiser M, Yafi A, Cinat M, et al. Noninvasive assessment of burn wound severity using optical technology: a review of current and future modalities. Burns. 2011;37:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammel HT, Hardy JD, Murgatroyd D. Spectral transmittance and reflectance of excised human skin. J Appl Physiol. 1956;9:257–264. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1956.9.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith AM, Mancini MC, Nie S. Bioimaging: second window for in vivo imaging. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:710–711. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chatterjee JS. A critical evaluation of the clinimetrics of laser Doppler as a method of burn assessment in clinical practice. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:123–130. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000202612.38320.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saladin KS, Porth CM. Anatomy & Physiology. Boston, Mass: WCB/McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulligan MS, Till GO, Smith CW, et al. Role of leukocyte adhesion molecules in lung and dermal vascular injury after thermal trauma of skin. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:1008–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perumanoor TJ. Visible Versus Near-infrared Light Penetration Depth Analysis in an Intralipid Suspension as it Relates to Clinical Hyperspectral Images. University of Texas at Arlington; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaines C, Poranki D, Du W, et al. Development of a porcine deep partial thickness burn model. Burns. 2013;39:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kempf M, Cuttle L, Liu PY, et al. Important improvements to porcine skin burn models, in search of the perfect burn. Burns. 2009;35:454–455. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holland AJ, Martin HC, Cass DT. Laser Doppler imaging prediction of burn wound outcome in children. Burns. 2002;28:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jeng JC, Bridgeman A, Shivnan L, et al. Laser Doppler imaging determines need for excision and grafting in advance of clinical judgment: a prospective blinded trial. Burns. 2003;29:665–670. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haslik W, Kamolz LP, Andel H, et al. The influence of dressings and ointments on the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of burn wounds by ICG video-angiography: an experimental setup. Burns. 2004;30:232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackson DM. Second thoughts on the burn wound. J Trauma. 1969;9:839–862. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196910000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]