Abstract

Langerhans cells (LCs) are the only dendritic cells of the epidermis and constitute the first immunological barrier against pathogens and environmental insults. The factors regulating LC homeostasis remain elusive and the direct circulating LC precursor has not yet been identified in vivo. Here we report an absence of LCs in mice deficient in the receptor for colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) in steady-state conditions. Using bone marrow chimeric mice, we have established that CSF-1 receptor–deficient hematopoietic precursors failed to reconstitute the LC pool in inflamed skin. Furthermore, monocytes with high expression of the monocyte marker Gr-1 (also called Ly-6c/G) were specifically recruited to the inflamed skin, proliferated locally and differentiated into LCs. These results identify Gr-1hi monocytes as the direct precursors for LCs in vivo and establish the importance of the CSF-1 receptor in this process.

Langerhans cells (LCs) are members of a family of highly specialized antigen-presenting cells called dendritic cells (DCs). Uniquely present in the epidermis, LCs form a tight cellular network that covers the entire body surface, constituting the first immunological barrier against the external environment. LCs are well equipped to ingest antigens present in the skin and to migrate to the regional lymph node in both steady-state and inflammatory conditions1,2. After being activated, LCs increase their expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and costimulatory molecules3 and migrate to T cell areas2 of draining lymph nodes, where they secrete T cell–attractant chemokines4 and interact with antigen-specific T cells. Whether migrating LCs serve mainly to carry antigens to blood-derived DCs in the draining lymph nodes or whether they directly prime or tolerize antigen-specific T cells is still debated5–8.

Given their importance in skin immunity, the mobilization of LCs to draining lymph nodes and the subsequent replacement of migrating cells by newly differentiated LCs must be tightly regulated events. Indeed, LC homeostasis is differentially regulated in quiescent and inflamed skin, and LCs are maintained by local radioresistant hematopoietic precursors that self-renew in situ in quiescent skin9. In contrast, after substantial injury skin-resident LCs are lost and are subsequently replaced by circulating precursors9. The identification of circulating LC precursors is critical for understanding the mechanisms that regulate skin immunity against pathogens and environmental insults. However, despite considerable work in this area, the identity of the immediate circulating LC precursor that repopulates LC populations in vivo remains elusive.

The presence of fully differentiated and functional DCs and LCs in adult osteopetrotic mice lacking expression of colony-stimulating factor (Csf1op/op mice)10,11, in which tissue macrophages and osteoclasts are much reduced12, has provided the basis for the hypothesis that LC development is independent of mononuclear phagocytes13. It has been argued that in the mouse, circulating CD11c+ cells distinct from monocytes give rise to all DC populations in vivo14, although whether this is true for LCs has not been specifically examined. In addition, human circulating CD11c+CD1a+ cells can be made to differentiate into LCs in vitro without additional cytokines, and human CD34+-derived CD1a+ cells give rise to LCs in vitro, although circulating CD14+ monocytes and CD34+-derived CD14+ are unable to do so15,16, supporting the hypothesis that LCs have a common origin with all DCs in vivo. On the other hand, human circulating monocytes17 and dermal CD14+ cells18 have been shown to differentiate into LC-like cells in vitro in the presence of a cytokine ‘cocktail’ containing transforming growth factor-β, a factor critical for LC development19. Thus, it is apparent that different precursors can be directed to differentiate into LCs in vitro, suggesting that some of the conditions used in those models are not physiologically relevant and that in vivo systems are much needed to delineate the mechanisms that regulate natural LC development. The fact that LC populations are repopulated by circulating LC precursors during skin injury provides a model with which to explore LC development directly in vivo9. Using that model here, we have characterized the direct circulating precursor that gives rise to LCs in vivo.

Results

LC development in Csf1op/op and CSF-1 receptor–deficient mice

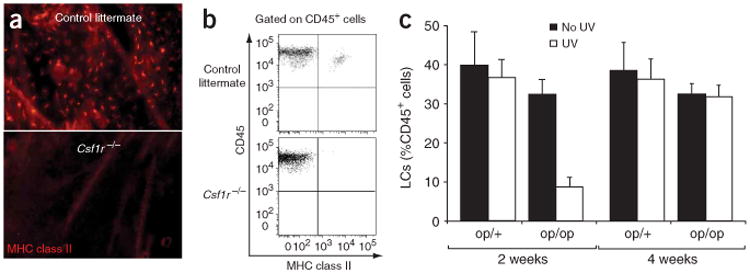

Although LCs are present in adult Csf1op/op mice13, LCs are greatly reduced in newborn Csf1op/op mice20. The fact that monocytes are increased by 72% in 2-week-old Csf1op/op mice21 compared with their numbers in newborn mice suggests that monocyte recovery with age21 may affect LC repopulation in adult Csf1op/op mice. As in Csf1op/op mice, LCs are absent from newborn mice that lack the receptor for CSF-1 (Csf1r−/−)20. To explore if, like Csf1op/op mice, Csf1r−/− mice recover LCs with age, we first quantified the pool of LCs in 3-week-old Csf1r−/− mice. Unexpectedly, we found that in contrast to the LC status of Csf1op/op mice13, LCs were totally absent from Csf1r−/− mice in steady-state conditions (Fig. 1a,b), suggesting a critical function for this cytokine receptor in LC homeostasis in the skin.

Figure 1.

LC development in CSF-1- and CSF-1R-deficient mice. (a,b) Immunofluorescence of epidermal sheets (a) and flow cytometry of cell suspensions (b) from 3-week-old Csf1r−/− or Csf1r+/+ control littermate FVB/NJ mice and stained with monoclonal ‘pan-anti–MHC class II’. Original magnification, ×10 (a). Dot plots (b) show propidium iodide–negative CD45+ epidermal cells that are positive for MHC class II. Results are representative of two separate experiments. (c) Flow cytometry of LCs repopulating the skin of 3-week-old Csf1op/op mice (op/op) or Csf1op/+ control littermates (op/+) with (UV) or without (No UV) exposure to ultraviolet light for 30 min, assessed 2 or 4 weeks after exposure. Data represent the mean percent of LCs (CD45+I-Ab+) among the total propidium iodide–negative CD45+ population in three individual mice.

CSF-1 (also called macrophage CSF) is a hematopoietic factor that regulates the survival, proliferation and differentiation of monocytes22. Because the CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R (CD115)) is a chief marker for monocytes23–25 and macrophages23, we hypothesized that monocytes participate in LC development in vivo. As LC replacement by circulating precursors occurs only during severe skin injury9, we revisited how LC homeostasis is restored in inflamed skin in both Csf1op/op and Csf1r−/− mice. We began by re-examining the function of CSF-1 in Csf1op/op mice, as results obtained with these mice were initially used to claim ontogenic independence of LCs and monocytes10,11. We exposed 3-week-old Csf1op/op or Csf1op/+ mice to ultraviolet light and monitored LC repopulation over time. We found that 2 weeks after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation, the percent of LCs among the total number of epidermal hematopoietic cells was substantially lower in Csf1op/op mice than in Csf1op/+ mice (7% versus 40%), but those recovered to wild-type numbers at 4 weeks after injury (Fig. 1c). The delay in LC repopulation in Csf1op/op mice might have been due to a slight reduction of monocytes compared with that of Csf1op/+ mice, although a more definite explanation was not possible because the number of monocytes and macrophages recovers with age in Csf1op/op mice and ultraviolet irradiation–mediated skin damage can be done only in adult mice. Therefore, we turned to more definitive approaches that would permit examination of the function of CSF-1 and monocytes in LC development.

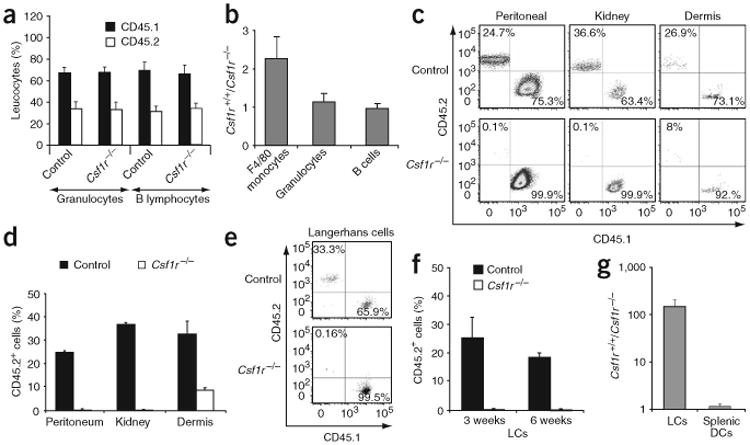

Function of CSF-1R in LC differentiation in vivo

Csf1r−/− mice have multiple developmental defects20, including severe osteopetrosis, that greatly reduce the bone marrow cavity size20 and that may therefore indirectly affect the pool of hematopoietic progenitors, including LC precursors. In addition, CSF-1R deficiency in FVB/NJ mice (the genetic background on which the gene deletion is most viable) causes death at approximately 3 weeks of age20,26, making any manipulation of these mice difficult. Therefore, to determine the function of CSF-1R in LC development in inflamed settings in adult mice, we reconstituted lethally irradiated CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice with CD45.2+ Csf1r−/− hematopoietic precursors so that the absence of CSF-1 signaling was restricted to hematopoietic cells and was independent of the secondary effects resulting from osteopetrosis. Moreover, because recruitment of monocytes to inflammatory sites modulates the recruitment of LC precursors through the secretion of proinflammatory molecules9, the failure of Csf1r−/− hematopoietic precursors to give rise to circulating monocytes could also affect LC recruitment without intrinsically affecting LC development. Thus, to test if CSF-1R is intrinsically required on the LC precursor, we reconstituted lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice with mixed hematopoietic precursors (30% CD45.2+ Csf1r−/− and 70% CD45.1+ wild-type, or 30% CD45.2+ Csf1r+/− (control littermate) and 70% CD45.1+ wild-type) and monitored the reconstitution of CD45.2+ Csf1r−/− or CD45.2+ Csf1r+/+ cells in the chimeric mice. The degree of blood B cell and granulocyte chimerism (30% CD45.2+ and 70% CD45.1+) reflected the percentage of mixed hematopoietic cells injected (Fig. 2a). Csf1r−/− progenitors were as efficient as Csf1r+/+ cells in giving rise to circulating B cells and granulocytes (Fig. 2a). Circulating monocytes are defined as low forward- and side-scatter cells expressing F4/80, CD11b and CD115 (CSF-1R) molecules25. As expected, we did not detect any CD115+ circulating cells in blood from Csf1r−/− mice and F4/80+ CD11b+ monocytes were variably reduced over time and were present at 50–60% of wild-type numbers (Fig. 2b). Consistent with the phenotype of Csf1op/op mice13,21 and Csf1r−/− mice20, Csf1r−/− peritoneal, kidney and dermal macrophages were much reduced in number in chimeric mice, confirming the idea that CSF-1R is intrinsically required for the differentiation of some tissue macrophages (Fig. 2c,d).

Figure 2.

Function of CSF-1R in LC differentiation in vivo. Lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice were reconstituted with mixed chimera bone marrow and were exposed 3 weeks later to ultraviolet light. (a) Mean percent peripheral blood Gr-1 (Ly-6G)+ granulocytes and B220+ B lymphocytes in control and Csf1r−/− mice 3 weeks after transplantation in six individual mice. (b) Wild-type versus Csf1r−/− leukocyte ratio, calculated as percent CD45.2+ Csf1r+/+ leukocytes divided by percent CD45.2+ Csf1r−/− leukocytes in six individual mice. (c) Propidium iodide–negative peritoneal, kidney and dermal F4/80+ CD11b+ macrophages that are CD45.1+ or CD45.2+ in control and Csf1r−/− chimeric mice, 3 weeks after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. (d) Mean percent CD45.2+ cells among total CD45+ (CD45.1+ and CD45.2+) cells in the corresponding macrophage populations in control and Csf1r−/− mice. (e) Propidium iodide–negative–gated LCs that are CD45.1+ or CD45.2+ in control and Csf1r−/− mice, 3 weeks after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. (f) Mean percent CD45.2+ LCs in control and Csf1r−/− mice 3 and 6 weeks after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. (g) Reduction in cells, calculated as percent CD45.2+ Csf1r+/+ LCs or spleen DCs divided by percent Csf1r−/− LCs or spleen DCs at 3 weeks after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. Results in c–g are representative of three or more separate experiments. Numbers in quadrants (c,e) indicate percentage of propidium iodide–negative total CD45+ gated cells that are CD45.1+ (bottom right) or CD45.2+ (top left).

To explore the function of CSF-1 in LC development, we exposed the chimeric mice to ultraviolet light 3 weeks after hematopoietic reconstitution9 and monitored the repopulation of mutant and wild-type LC populations in skin with ultraviolet irradiation injury. Analysis of chimeric mice 3 weeks after ultraviolet irradiation showed that CD45.2+ Csf1r−/− LCs were absent (0.16% of total LCs) from all mice analyzed, whereas there was efficient reconstitution by CD45.2+ LCs derived from Csf1+/+ control littermates (33% of total LCs, which corresponds to the blood chimerism; Fig. 2e). The deficiency in Csf1r−/− LCs in the mixed chimeras persisted for at least 6 weeks after ultraviolet irradiation (Fig. 2f), establishing the idea that Csf1r−/− hematopoietic cells are unable to differentiate into LCs in inflamed skin. In contrast, there was similar reconstitution of mutant and wild-type splenic DCs (Fig. 2g), suggesting that the requirement for CSF-1R is restricted to LCs.

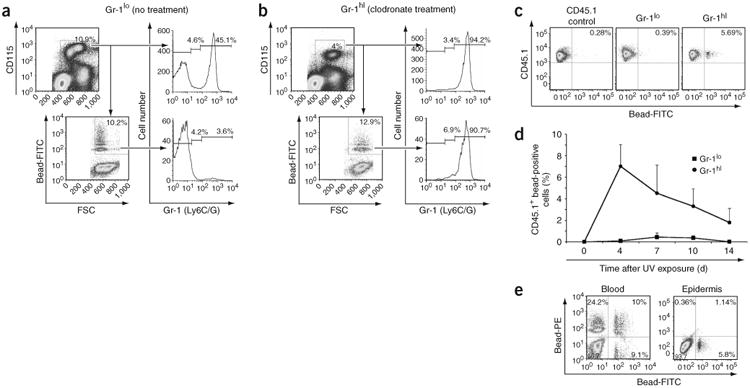

Labeling monocyte subsets in vivo

Because CSF-1R is important for monocyte and macrophage differentiation in vivo, we explored the capacity of monocytes to repopulate LC populations in inflamed skin. Two subsets of blood monocytes with different migrating properties have been described in mouse blood. These include the classical Gr-1hiCCR2+ monocytes and the more mature Gr-1loCCR2− monocyte subset24,25,27. In humans, these subsets correspond respectively to the classical CD14+CD16− and the more infrequent CD14loCD16+ monocyte subsets27–29. To avoid manipulating blood monocytes ex vivo, we monitored the fate of monocytes directly in vivo by labeling them with fluorescent latex beads30. We used congenic ‘CD45.1+ bone marrow→CD45.2+’ chimeric mice to distinguish circulating precursors (CD45.1+) from skin-resident (CD45.2+) LCs9 (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Intravenous injection of fluorescent latex beads labeled mainly Gr-1loCD115+ monocytes (Fig. 3a), whereas bead injection 1 d after the elimination of circulating monocytes using clodronate-loaded liposomes25 labeled mainly Gr-1hiCD115+ monocytes (Fig. 3b). Thus, all ‘bead-positive’ monocytes were either CD45.1+Gr-1hi monocytes (Gr-1hi group) or CD45.1+Gr-1lo monocytes (Gr-1lo group). At 4 h after injection of beads, we exposed chimeric mice to ultraviolet light (Supplementary Fig. 1 online).

Figure 3.

Gr-1hi monocytes infiltrate and proliferate in situ in ultraviolet irradiation–inflamed skin. Mice were treated as described in Supplementary Figure 1 online. (a,b) At 1 d after bead injection, all monocytes positive for fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled beads are mainly Gr-1lo in the absence of clodronate treatment (a) but are Gr-1hi when beads are injected after mice are treated with clodronate-loaded liposomes (b). Data are representative of at least five separate experiments. (c) At 4 d after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation, bead-positive Gr-1hi but not bead-positive Gr-1lo monocytes are present in the skin. (d) Percent propidium iodide–negative CD45.1+ bead-positive cells that infiltrate the epidermis in Gr-1lo and Gr-1hi groups after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. (e) Gr-1hi monocytes labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–positive beads before exposure to ultraviolet light are recruited to the skin, whereas Gr-1hi monocytes labeled with phycoerythrin-positive beads 4 d after exposure to ultraviolet light fail to enter the skin, suggesting that Gr-1hi monocytes do not enter the skin 4 d after skin injury. Numbers in quadrants, beside outlined areas and above bracketed lines indicate percentage of cells in each area. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; FSC, forward scatter; PE, phycoerythrin; UV, ultraviolet. Data in c–e are representative of three separate experiments.

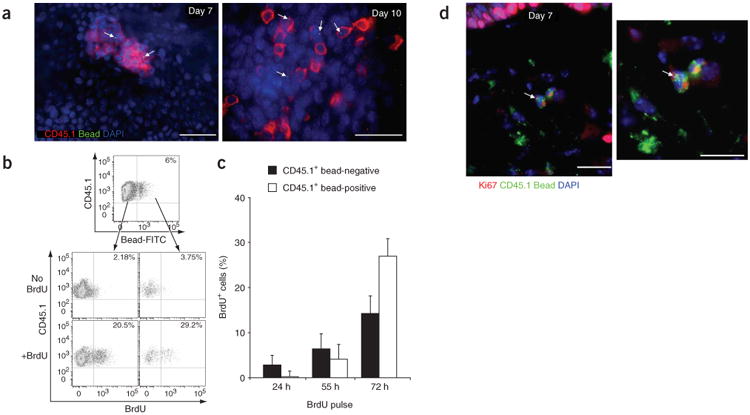

Gr-1hi monocytes infiltrate and proliferate in inflamed skin

We detected CD45.1+ bead-positive cells only in inflamed skin from mice of the Gr-1hi group (Fig. 3c,d). CD45.1+Gr-1hi circulating monocytes began to infiltrate the skin 18 h after injury (data not shown) but failed to do so after 4 d (Fig. 3e). At day 4 after ultraviolet treatment, bead-positive cells in the skin represented 6–10% of total infiltrating cells (Fig. 3c,d), which is similar to the labeling efficiency of blood monocytes (Fig. 3b). Gr-1hi monocytes formed many clusters in the skin between day 4 and day 7 after ultraviolet injury (Fig. 4a, top) and began to detach between day 7 and day 10 (Fig. 4a, bottom). To explore whether these clusters corresponded to proliferating cells or only to aggregated cells, we administered 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to mice 4 d after exposure to ultraviolet light. Because at that time point circulating monocytes failed to migrate to the skin (Fig. 3e), BrdU uptake by skin monocytes should have reflected only local proliferation. BrdU labeling showed that monocytes proliferated actively between day 4 and day 7 (Fig. 4b,c). We confirmed local proliferation of recruited bead-positive monocytes by in situ immunostaining with the cell cycle protein Ki67 (Fig. 4d), establishing that the bead-positive clusters were formed by proliferating monocytes.

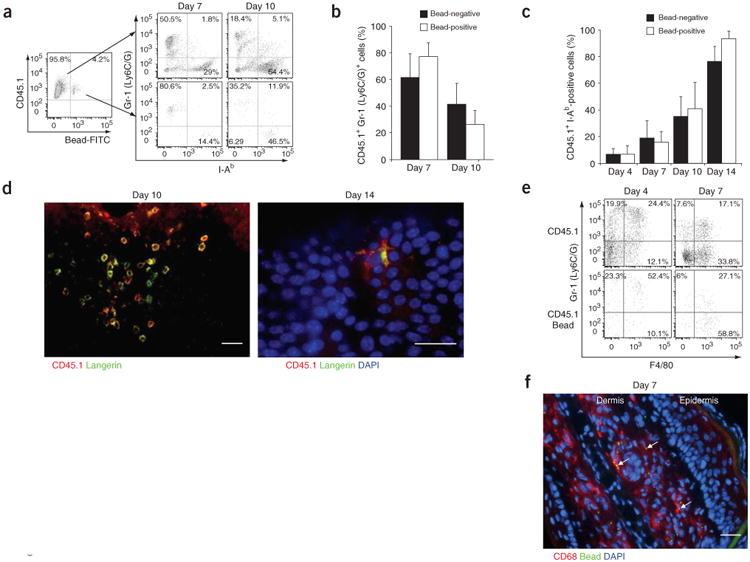

Figure 4.

Bead-positive Gr-1hi monocytes differentiate into dermal macrophages and epidermal LCs in inflamed skin. (a) Epidermal sheets stained for CD45.1 (red) and DAPI (blue) at 7 d and 10 d after ultraviolet irradiation. Fluorescein isothiocyanate–positive beads are bright green dots (arrows). Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are representative of at least four separate experiments. (b) Percent BrdU+ cells in recruited CD45.1+ bead-negative or CD45.1+ bead-positive populations in the epidermis after a 72-hour pulse of BrdU. Data are representative of three separate experiments. (c) Percent CD45.1+ bead-negative BrdU+ cells and CD45.1+ bead-positive BrdU+ cells after BrdU pulses of varying times. Data are one representative experiment (n = 3). (d) Frozen sections of skin stained for Ki67 (red), CD45.1 (green) and DAPI (blue), 7 d after ultraviolet treatment. Right, higher magnification. Fluorescein isothiocyanate–positive beads are bright green dots (arrows). Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are representative of two separate experiments.

Differentiation of Gr-1hi monocytes in situ

Beginning at day 7 after ultraviolet irradiation, skin-infiltrating monocytes decreased their proliferation rate (data not shown) and began to downregulate Gr-1 expression and upregulate expression of MHC class II molecules (Fig. 5a–c). Shortly thereafter, round monocytes detached from the clusters (Fig. 5d, left, and Fig. 4a) and began to express the LC-specific marker langerin (Fig. 5d). Along with those phenotypic changes, round monocytes developed dendrites at approximately day 14 (Fig. 5d), and by 3 weeks after ultraviolet treatment, all CD45.1+ cells in the epidermis acquired an LC morphology and expressed langerin (data not shown). In addition to the development of some Gr-1hi monocytes into LCs, a large fraction of these monocytes differentiated into F4/80hiCD68hi dermal macrophages. The differentiation of bead-positive monocytes into dermal macrophages in the dermis was faster and occurred within 6–7 d (Fig. 5e,f).

Figure 5.

Skin-infiltrating Gr-1hi monocytes differentiate into LCs. (a) Gr-1 and I-Ab expression patterns in bead-negative CD45.1+ and bead-positive CD45.1+ populations recruited into inflamed epidermis at days 7 and 10 after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. Data are representative of three separate experiments. (b,c) Mean percent bead-negative or bead-positive CD45.1+ cells that are Gr-1+ (b) or I-Ab+ (c) at various times after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation (n = 3). (d) Epidermal sheets stained for CD45.1 (red), langerin (green) and DAPI (blue) at various times after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. Scale bars, 10 μm. Images are representative of two individual mice. (e) Gr-1 and F4/80 expression patterns in bead-negative and bead-positive propidium iodide–negative CD45.1+ populations recruited into inflamed dermis at days 4 and 7 after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation (n = 2). (f) Frozen sections of skin stained for CD68 (red) and DAPI (blue), 7 d after ultraviolet treatment. Beads are bright green dots (arrows). Scale bar, 10 μm. Images are representative of two individual mice. Numbers in quadrants (a,e) indicate percentage of cells positive or negative for the marker.

Adoptive transfer of Gr-1hi monocytes

To confirm the LC differentiation potential of Gr-1hi monocytes in vivo, we adoptively transferred purified CD45.1+Gr-1hi monocytes into CD45.2+ recipient mice deficient in CCR2 and CCR6. Because CCR2 and CCR6 are required for LC repopulation in vivo in inflamed skin9,31, the absence of CCR2 and CCR6 expression in recipient mice should decrease the recruitment of endogenous LC precursors to inflamed skin. This would give a competitive advantage to the adoptively transferred LC precursors, thereby facilitating their detection.

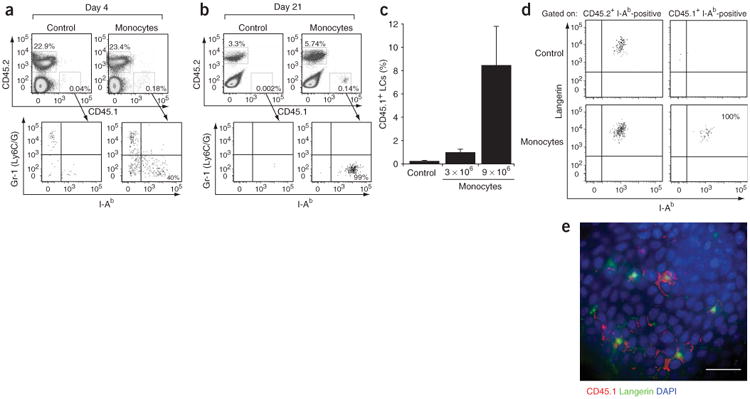

We injected Gr-1hi monocytes intravenously 1 d after exposing recipient mice to ultraviolet irradiation. We detected a substantial population of CD45.1+ Gr-1+ cells in the recipient epidermis 4 d later, and a fraction of these cells had begun to downregulate Gr-1 and upregulate MHC class II molecules (Fig. 6a). Consistent with the results reported above, CD45.1+Gr-1hi monocytes recruited to inflamed skin differentiated into epidermal Gr-1−I-Ab+langerin+ LCs within 3 weeks (Fig. 6b–e). The number of CD45.1+-derived LCs was proportional to the number of transferred CD45.1+ monocytes (Fig. 6c), suggesting that Gr-1hi monocytes are the precursors of LCs in vivo. Analysis of epidermal sheets 7 weeks after monocyte transfer and exposure to ultraviolet irradiation (Fig. 6e) showed accumulation of ‘islets’ of monocyte-derived LCs in defined area of the epidermis, consistent with the monocyte clustering noted above (Fig. 4a). In contrast, we detected no LCs in the control group injected with MHC class II–positive CD11c+ bone marrow cells, further indicating that the common CD11c+ precursor described in the blood14 and the bone marrow32, although able to give rise to all DC populations, probably does not participate in LC development in vivo.

Figure 6.

Adoptive transfer of Gr-1hi monocytes in vivo. (a,b) Top, percent propidium iodide–negative–gated epidermal cells that are CD45.1+ or CD45.2+ in mice injected with monocytes or control (I-Ab+ CD11c+) populations. Bottom, Gr-1 and I-Ab expression patterns of gated epidermal CD45.1+ cells in mice injected with monocytes or control (I-Ab+ CD11c+) populations, 5 d (a) or 21 d (b) after exposure to ultraviolet irradiation. Results are representative of three separate experiments. (c) Percent CD45.1+ LCs derived from adoptively transferred CD45.1+ cells among total LCs. Data represent percent LCs derived from 3 × 106 or 9 × 106 monocytes or 9 × 106 enriched bone marrow I-Ab+CD11c+ cells (Control) and are from one representative experiment (n = 3). (d) Langerin expression pattern of gated CD45.2+ I-Ab+ and CD45.1+ I-Ab+ epidermal cells in mice 6 weeks after adoptive transfer of CD45.1+ monocytes. Results are representative of two individual mice. (e) Epidermal sheet stained with CD45.1 (red), langerin (green) and DAPI (blue). Epidermis is from a CD45.2+ mouse, 6 weeks after adoptive transfer of 9 × 106 CD45.1+ monocytes. Scale bar, 10 μm. Results are representative of two individual mice.

Discussion

Many possible LC precursors have been described in the literature. One strong candidate has been the circulating CD11c+ blood DC. Indeed, human CD11c+ circulating blood DCs can give rise to LCs without additional cytokines in vitro16, whereas CD11c+ circulating cells and bone marrow CD11c+ cells in mice can give rise to all lymphoid organ DCs and plasmacytoid DCs in vivo and in vitro14,32. Although monocytes can be ‘directed’ to become LCs in certain conditions17,33, the weight of the evidence in vivo and in vitro suggests that LCs do not derive from monocytes. Indeed, nonmonocytic precursors can give rise to LCs in vitro15,16 and mice with fewer monocytes still contain LCs in the steady state13.

In contrast to those results, here we have demonstrated that Gr-1hi monocytes are the direct LC precursors in vivo and that CSF-1R is critical for this process. First, bone marrow progenitors that lacked CSF-1R failed to give rise to tissue macrophages and LCs in inflamed skin. Second, when we tagged circulating monocytes in vivo with fluorescent latex beads and monitored their fate in inflamed skin (in which LCs had been ablated) over time, Gr-1hi monocytes homed to inflamed skin and proliferated in situ for 3–4 d before differentiating into LCs within 2–3 weeks. Third, adoptively transferred Gr-1hi monocytes migrated to inflamed skin within a few days after LCs were ablated by ultraviolet irradiation and gave rise to new LCs within 3 weeks. Fourth, 3-week-old mice deficient for CSF-1R lacked LCs in quiescent skin, suggesting that expression of CSF-1R is required for LC development in vivo in both steady-state and inflammatory conditions.

We have also shown that the requirement for CSF-1R is specific to the LC precursor, as mice transplanted with a mixture of Csf1r−/− and Csf1r+/+ hematopoietic precursors lacked CSF-1R-deficient LCs but not CSF-1R-deficient splenic DCs. Whether other DC populations in lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs, as well as plasmacytoid DCs, require CSF-1R for their development in vivo will require further study. In addition to the lack of CSF-1R-deficient LCs in the skin, chimeric mice also lacked CSF-1R-deficient dermal, peritoneal and kidney macrophages but not liver macrophages, suggesting that LCs share similar developmental pathways with some but not all tissue macrophages. These results established that CSF-1R is required for LC differentiation in inflamed skin.

Our finding that Csf1r−/− mice lacked LCs suggests that CSF-1R may also be required for LC development in the steady state; the fact that constitutive expression of CSF-1 occurs in quiescent skin further supports that hypothesis34. However, as Csf1r−/− mice have developmental defects that may indirectly affect LC differentiation in vivo20, an experiment to establish the function of CSF-1R in LC development in the steady state will be the demonstration that Csf1r−/− LCs fail to develop normally in quiescent skin in wild-type mice reconstituted with Csf1r−/− bone marrow. Unfortunately, that is difficult to test experimentally because replacement of skin-resident LCs by circulating precursors occurs only in injured skin, a treatment that radically disrupts the steady state9.

The absence of LC development in Csf1r−/− mice reported here contrasts with published reports of LC development in Csf1op/op mice10,11. The difference between Csf1op/op and Csf1r−/− mice may be related to the difference in strain background (Csf1op/op is outbred; Csf1r−/− is inbred FVB/NJ), possible ‘leakiness’ of the Csf1op mutation or stimulation of CSF-1R signaling directly or indirectly via a second ligand20,22,35. Indeed, CSF-1 is widely expressed in the mouse and although the two main forms of CSF-1 are absent from Csf1op/op mice35, it is possible that expression of alternative CSF-1 splice variant depends on the cell type and/or tissue36. CSF-1 is constitutively expressed in the skin34 and it is likely that skin CSF-1 (ref. 34) is critical for LC development in vivo. Thus, it might be useful to analyze what isoform of CSF-1 is expressed in the skin and whether skin CSF-1 persists in Csf1op/op mice. Finally, another possible explanation for the strain difference is that other cytokines signal through CSF-1R and drive LC differentiation. In support of that possibility, the ligand for the tyrosine kinase receptor Flt3 is critical for LC differentiation in vivo37. Because Flt3 has some homology with CSF-1R38, it might be useful to determine whether the Flt3 ligand can drive LC differentiation in Csf1op/op mice.

CSF-1 is critical to the survival, proliferation, differentiation and/or maturation of the mononuclear phagocyte lineage22. Injection of CSF-1 into animals increases the number of monocytes in peripheral blood, whereas no changes are noted in other myeloid cells39. The ability to respond to CSF-1 alone is an early event in monocyte commitment, and the specificity of CSF-1 for monocytic cells seems to be determined in part by increased expression of its receptor during or after commitment to the monocytic lineage40. However, the precise function of CSF-1 in monocyte commitment remains controversial. One hypothesis is that CSF-1 drives the differentiation of monocytes into tissue macrophages41, although other studies have led to the hypothesis that CSF-1 provides a survival signal to the differentiating monocytes and that surviving cells use an intrinsic developmental program to become mature macrophages42–44. Our data showing that Csf1r−/− monocytes were only slightly fewer in number than wild-type monocytes, along with the capacity of Csf1r−/− monocytes to migrate to inflamed skin (data not shown), suggest that CSF-1 is not critical to monocyte production or recruitment to the skin but instead controls monocyte proliferation, survival or differentiation into LCs in the skin.

Intravenous injection of fluorescent beads into ‘CD45.1 bone marrow→CD45.2’ chimeric mice is a useful tool for monitoring the sequence of cellular events that lead a monocyte to become an LC in the skin. We found that once in the epidermis, Gr-1hi monocytes formed many proliferating clusters, downregulated Gr-1 and upregulated MHC class II molecules. After a few days, the ‘maturing’ monocytes stopped proliferating, detached from the clusters and progressively acquired a dendritic morphology, including expression of the LC-specific marker langerin. Full differentiation into MHC class II–positive langerin-positive LCs occurred within 2 to 3 weeks. Notably, LC differentiation in newborn mice follows a similar pattern. Several studies have identified round CD45+ MHC class II–low F4/80+ myeloid cells in the epidermis of newborn mice45,46. Like the changes in monocytes that develop into LCs in inflamed adult skin, round epidermal F4/80+ hematopoietic cells progressively acquire a dendritic morphology and upregulate MHC class II expression, followed a few days later by expression of langerin47. Complete LC differentiation in the epidermis in newborn mice, as in adult mice treated with ultraviolet irradiation, occurs within approximately 3 weeks45,47. Those data, together with the fact that 3-week-old Csf1r−/− mice lack skin LCs, suggest that the round F4/80+ hematopoietic cells seen repopulating the ultraviolet-treated skin may correspond to an embryonic monocyte that progressively differentiates in a CSF-1-dependent way into an LC precursor able to self-renew in quiescent skin. We have also demonstrated that monocyte-derived LCs persisted more than 7 weeks after transfer, suggesting that LC differentiation was not transient. Whether monocyte-derived LCs, like LCs in quiescent skin, are able to self-renew locally will require further study.

Gr-1hi monocytes express the inflammatory chemokine receptor CCR2 and lose both Gr-1 and CCR2 after maturation25,27. The unique capacity of Gr-1hi monocytes to home to inflamed skin and to differentiate into LCs is consistent with our finding that LC repopulation in inflamed skin was dependent on CCR2 (refs. 9,31). However, our finding that the classical Gr-1hiCCR2+ monocyte subset served as the precursor for LCs was unexpected, as it represents evidence that these monocytes give rise to a distinct population of DCs in vivo. Past studies examining the development of DCs from monocytes in vitro and in vivo without the addition of exogenous cytokines (which may not represent physiological conditions) have indicated only the function of nonclassical monocyte subsets as DC precursors24,29. In addition, skin-draining lymph node DCs that do not take up residence in skin but instead transiently emigrate through the dermis do not derive from Gr-1hi monocytes and are independent of CCR2 (ref. 24). Thus, it is evident that different skin-derived DC populations can, in common, arise from monocytes, although from different types of monocyte subsets. Although it is likely that most Gr-1hi monocytes or their human equivalents differentiate into macrophages, a fraction of them, perhaps only in response to factors present in the epidermal environment, begin to proliferate and develop into LCs. Those results are in agreement with a report showing differentiation of human CCR2+CD14+ monocytes into LCs in an in vitro model of reconstructed human skin33, consistent with the importance of the epidermal environment in inducing monocyte differentiation into LCs.

Our results demonstrating the critical involvement of CSF-1 in LC development in vivo may have potential important therapeutic applications. Indeed, LC histiocytosis is characterized by the infiltration of large number of LCs organs and tissues throughout the body48. LC histiocytosis remains an ‘enigmatic’ disease with features of cancer and inflammatory processes, and treatment of patients with this disease has included both chemotherapy and immunosuppressors48. Our results demonstrating involvement of CSF-1 in LC development, together with the published finding that CSF-1 is increased in patients with LC histiocytosis49, identify CSF-1 as a new potential therapeutic target for the treatment of these patients.

In summary, our results have identified Gr-1hi monocytes as the direct circulating LC precursors in vivo and have established the critical involvement of CSF-1R in the migration and development of skin LCs. We also monitored the sequence of cellular events that lead a Gr-1hi monocyte to become an LC in the skin. Gr-1hi monocytes homed to inflamed epidermis and dermis, where they actively proliferated before beginning to differentiate into either dermal macrophages or epidermal LCs and repopulated the entire LC pool within 2–3 weeks. The identification of these mechanistic features of LC development and biology should contribute to ongoing efforts to engineer immune responses in vaccine design and tumor immunotherapy50 and to a better understanding of the immune response to skin pathogens.

Methods

Animals

Female C57BL/6 (CD45.2+) and congenic C57BL/6 CD45.1+ mice 5–8 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. CCR2- and CCR6-deficient C57BL/6 mice (Ccr2−/−Ccr6−/− mice) were generated by crossing of Ccr2−/− mice51 with Ccr6−/− mice52 and were maintained in our animal facility (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York). Csf1r−/− mice on the FVB/NJ background were generated as described26. Csf1op/+ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Csf1op/op mice were generated in our animal facility (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York) by breeding of Csf1op/+ mice. All mouse protocols were approved by the Institutional Committee on Animal Welfare of the Mount Sinai Medical School (New York, New York).

Flow cytometry

Multiparameter analyses were made on an LSR II (Becton Dickinson) and were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Monoclonal antibodies to mouse I-Ab, CD11b, CD11c, CD45, CD45.1, CD45.2, CD115, F480 and Gr-1 (Ly6C/G), the corresponding isotype controls and the secondary reagents (allophycocyanin, peridinine chlorophyll protein and phycoerythrin–indotricarbocyanine–conjugated streptavidin) were purchased from PharMingen. Monoclonal antibody to langerin was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Transplantation of bone marrow and fetal liver cells and ultraviolet irradiation

Eight-week-old recipient CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice were lethally irradiated with 1,200 rads delivered in two doses of 600 rads each, 3 h apart, and were injected intravenously with a mixture of 30% Csf1r−/− CD45.2+ fetal liver cells and 70% syngeneic wild type CD45.1+ bone marrow or a mixture of 30% Csf1r+/+ CD45.2+ control littermate fetal liver cells and 70% syngeneic wild-type CD45.1+ bone marrow. We used fetal liver as a source of Csf1r−/− hematopoietic precursors cells because C57BL/6 Csf1r−/− mice die in utero26. For bead labeling experiments, CD45.2+ recipient C57BL/6 mice were lethally irradiated and were injected intravenously with 2 × 106 bone marrow cells isolated from congenic CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice. Hematopoietic engraftment was analyzed by measurement of blood chimerism 2 weeks after transplantation. Exposure to ultraviolet light was done between 3 and 4 weeks after transplant as described9.

Labeling of blood monocytes

Fluorescein isothiocyanate–or phycoerythrin-conjugated plain microspheres 0.5 μm in diameter (Polysciences) were diluted 1:25 in PBS, and 250 μl of the solution was injected into the lateral tail vein for labeling of Gr-1lo monocytes. For labeling of Gr-1hi monocytes, 250 μl of liposomes containing clodronate were injected intravenously, followed by intravenous injection of 250 μl fluorescent microspheres 16–18 h later. Clodronate was a gift from Roche and was incorporated into liposomes as described53.

Isolation of spleen DCs and peritoneal, kidney and dermis macrophages

Spleen, dermis and kidney cell suspensions were isolated as described9 and were analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of CD45.2+ and CD45.1+ CD11c+CD11b+ DCs or CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages. Peritoneal lavage cells were isolated by flushing of the peritoneal cavity with 4–6 ml of PBS supplemented with 0.5% FCS and were analyzed for the presence of CD45.2+ and CD45.1+ CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages.

LC isolation and analyses

The presence of LCs was assessed by flow cytometry of epidermal cell suspensions by gating on propidium iodide–negative CD45+ I-Ab+ or by immunofluorescence analysis of epidermal sheets as described9.

BrdU labeling and analysis

‘CD45.1→CD45.2’ bone marrow chimeric mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg BrdU (Sigma) resuspended in PBS to ensure immediate availability and were given BrdU (0.4 mg/ml) in sterile drinking water changed daily for variable BrdU pulses. Epidermal cell suspensions were prepared at different times after BrdU administration and were analyzed for BrdU incorporation with the BrdU Flow Kit (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Monocyte transfer experiments

Bone marrow cell suspensions isolated from CD45.1+ C57BL/6 mice were depleted of I-Ab+ and CD11c+ cells by immunomagnetic cell depletion using MACS technology (Miltenyi Biotech) and were then positively selected for bone marrow monocytes by MACS immunomagnetic cell selection with monoclonal antibodies to Gr-1 (Ly6C/G) and CD115. The positive fraction contained less than 0.2% CD11c+ MHC class II–positive contaminating cells. C57BL/6 CD45.2+ Ccr2−/−Ccr6−/− double-knockout recipient mice were exposed to ultraviolet light 24 h before intravenous injection with 9 × 106 CD45.1+Gr-1+CD115+ bone marrow monocytes or 9 × 106 CD45.1+I-A CD11c+ bone marrow cells. The recruitment of CD45.1+ monocytes to the skin of recipient CD45.2+ mice was analyzed 4 d after transfer; the presence of CD45.1+ LCs in the epidermis was analyzed 3 and 6 weeks later.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Epidermal sheets were stained with mouse antibody to mouse CD45.1 (anti–mouse CD45.1; eBioscience) and goat anti-langerin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and detection was done with indocarbocyanine-conjugated monoclonal donkey anti-mouse and indodicarbocya-nine-conjugated monoclonal donkey anti-goat (Jackson Immunoresearch). For staining of frozen sections, skin was ‘snap frozen’ in optimum cutting temperature compound and sections 8 mm in thickness were prepared, were fixed in 100% acetone for 5 min and were rinsed in PBS. Primary antibodies included biotinylated mouse anti-CD45.1 (eBioscience), rat anti-CD68 (Serotech), rat anti-I-Ab (Pharmingen) and rat anti-Ki-67 (Becton Dickinson Biosciences). Carbocyanine-conjugated streptavidin and indocarbocyanine-conjugated monoclonal donkey anti-rat (Jackson Immunoresearch) were used for detection. Slides were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired with a Leica DMRA2 fluorescence microscope (Wetzlar) and a digital Hamamatsu CCD camera and were analyzed with Openlab software (Improvision).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Association Francaise Contre le Cancer (F.G.), the German Research Foundation (F.T.), the National Institutes of Health (AI49653 to G.J.R., and CA32551 and CA26504 to E.R.S.), the American Society of Hematology (X.-M.D.) and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (X.-M.D.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Immunology website.

Competing Interests Statement: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hemmi H, et al. Skin antigens in the steady state are trafficked to regional lymph nodes by transforming growth factor-β1-dependent cells. Int Immunol. 2001;13:695–704. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kripke ML, Munn CG, Jeevan A, Tang JM, Bucana C. Evidence that cutaneous antigen-presenting cells migrate to regional lymph nodes during contact sensitization. J Immunol. 1990;145:2833–2838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuler G, Steinman RM. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells mature into potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1985;161:526–546. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.3.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang HL, Cyster JG. Chemokine up-regulation and activated T cell attraction by maturing dendritic cells. Science. 1999;284:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayerova D, Parke EA, Bursch LS, Odumade OA, Hogquist KA. Langerhans cells activate naive self-antigen-specific CD8 T cells in the steady state. Immunity. 2004;21:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allan RS, et al. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8α+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science. 2003;301:1925–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.1087576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kissenpfennig A, et al. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo: dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhan scells. Immunity. 2005;22:643–654. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, et al. Inducible ablation of mouse Langerhans cells diminishes but fails to abrogate contact hypersensitivity. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:569–576. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merad M, et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witmer-Pack MD, et al. Identification of macrophages and dendritic cells in the osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:1021–1029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi K, Naito M, Shultz LD. Differentiation of epidermal Langerhans cells in macrophage colony-stimulating-factor-deficient mice homozygous for the osteopetrosis (op) mutation. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:46S–47S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12668982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiktor-Jedrzejczak WW, Ahmed A, Szczylik C, Skelly RR. Hematological characterization of congenital osteopetrosis in op/op mouse. Possible mechanism for abnormal macrophage differentiation. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1516–1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W, Gordon S. Cytokine regulation of the macrophage (MΦ) system studied using the colony stimulating factor-1-deficient op/op mouse. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:927–947. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.del Hoyo GM, et al. Characterization of a common precursor population for dendritic cells. Nature. 2002;415:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/4151043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caux C, et al. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent dendritic cell pathways in response to GM-CSF+TNF-α. J Exp Med. 1996;184:695–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito T, et al. A CD1a+/CD11c+ subset of human blood dendritic cells is a direct precursor of Langerhans cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:1409–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geissmann F, et al. Transforming growth factor β1, in the presence of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin 4, induces differentiation of human peripheral blood monocytes into dendritic Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:961–966. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larregina AT, et al. Dermal-resident CD14+ cells differentiate into Langerhans cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1151–1158. doi: 10.1038/ni731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Farr AG, Udey MC. A role for endogenous transforming growth factor β1 in Langerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growth factor β1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2417–2422. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai XM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99:111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cecchini MG, et al. Role of colony stimulating factor-1 in the establishment and regulation of tissue macrophages during postnatal development of the mouse. Development. 1994;120:1357–1372. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pixley FJ, Stanley ER. CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrne PV, Guilbert LJ, Stanley ER. Distribution of cells bearing receptors for a colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) in murine tissues. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:848–853. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu C, et al. Role of CCR8 and other chemokine pathways in the migration of monocyte-derived dendritic cells to lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1231–1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sunderkotter C, et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172:4410–4417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dai XM, Zong XH, Akhter MP, Stanley ER. Osteoclast deficiency results in disorganized matrix, reduced mineralization, and abnormal osteoblast behavior in developing bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1441–1451. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Liebman RM, Schakel K. The CD16+ (FcγRIII+) subset of human monocytes preferentially becomes migratory dendritic cells in a model tissue setting. J Exp Med. 2002;196:517–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tacke F, et al. Immature monocytes acquire antigens from other cells in the bone marrow and present them to T cells after maturing in the periphery. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052119. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merad M, et al. Depletion of host Langerhans cells before transplantation of donor alloreactive T cells prevents skin graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2004;10:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nm1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruno L, Seidl T, Lanzavecchia A. Mouse pre-immunocytes as non-proliferating multipotent precursors of macrophages, interferon-producing cells, CD8α+ and CD8α− dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3403–3412. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3403::aid-immu3403>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Ebert LM, Walz A, Moser B. Cutaneous CXCL14 targets blood precursors to epidermal niches for Langerhans cell differentiation. Immunity. 2005;23:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan GR, et al. Rescue of the colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1)-nullizygous mouse (Csf1op/Csf1op) phenotype with a CSF-1 transgene and identification of sites of local CSF-1 synthesis. Blood. 2001;98:74–84. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth P, Stanley ER. The biology of CSF-1 and its receptor. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;181:141–167. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77377-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hume DA, Favot P. Is the osteopetrotic (op/op mutant) mouse completely deficient in expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor? J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1995;15:279–284. doi: 10.1089/jir.1995.15.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mende I, Karsunky H, Weissman IL, Engleman EG, Merad M. Flk2+ myeloid progenitors are the main source of Langerhans cells. Blood. 2005 doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hannum C, et al. Ligand for FLT3/FLK2 receptor tyrosine kinase regulates growth of haematopoietic stem cells and is encoded by variant RNAs. Nature. 1994;368:643–648. doi: 10.1038/368643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hume DA, Pavli P, Donahue RE, Fidler IJ. The effect of human recombinant macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) on the murine mononuclear phagocyte system in vivo. J Immunol. 1988;141:3405–3409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tushinski RJ, et al. Survival of mononuclear phagocytes depends on a lineage-specific growth factor that the differentiated cells selectively destroy. Cell. 1982;28:71–81. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metcalf D. The granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors. Science. 1985;229:16–22. doi: 10.1126/science.2990035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Korn AP, Henkelman RM, Ottensmeyer FP, Till JE. Investigations of a stochastic model of haemopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 1973;1:362–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakahata T, Gross AJ, Ogawa M. A stochastic model of self-renewal and commitment to differentiation of the primitive hemopoietic stem cells in culture. J Cell Physiol. 1982;113:455–458. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041130314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lagasse E, Weissman IL. Enforced expression of Bcl-2 in monocytes rescues macrophages and partially reverses osteopetrosis in op/op mice. Cell. 1997;89:1021–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romani N, Schuler G, Fritsch P. Ontogeny of Ia-positive and Thy-1-positive leukocytes of murine epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;86:129–133. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12284135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elbe A, et al. Maturational steps of bone marrow-derived dendritic murine epidermal cells. Phenotypic and functional studies on Langerhans cells and Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells in the perinatal period. J Immunol. 1989;143:2431–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tripp CH, et al. Ontogeny of Langerin/CD207 expression in the epidermis of mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:670–672. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beverley PC, Egeler RM, Arceci RJ, Pritchard J. The Nikolas Symposia and histiocytosis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:488–494. doi: 10.1038/nrc1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rolland A, et al. Increased blood myeloid dendritic cells and dendritic cell-poietins in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:3067–3071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banchereau J, et al. Immune and clinical responses in patients with metastatic melanoma to CD34+ progenitor-derived dendritic cell vaccine. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6451–6458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boring L, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C–C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2552–2561. doi: 10.1172/JCI119798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cook DN, et al. CCR6 mediates dendritic cell localization, lymphocyte homeostasis, and immune responses in mucosal tissue. Immunity. 2000;12:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.