Abstract

Objective

The study was designed to evaluate the impact of an interactive computer program developed to empower prenatal communication of women with restricted literacy skills.

Study Design

83 women seeing 17 clinicians were randomized to a computer-based communication activation intervention, Healthy Babies Healthy Moms (HBHM), or prenatal education, Baby Basics (BB), prior to their prenatal visit. Visit communication was coded with the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) and post-visit satisfaction was reported.

Results

Participants were on average 24 years of age and 25 weeks pregnant; 80% were African American. Two-thirds scored ≤ 8th grade on a literacy screener. Women with literacy deficits were more verbally active, disclosed more medical and psychosocial/lifestyle information and were rated as more dominant by coders in the HBHM group relative to counterparts in the BB group (all p<.05). Clinicians were less verbally dominant and more patient-centered with literate HBHM relative to BB group women (p<.05); there was a similar, non-significant trend (p<.1) for lower literate women. Clinicians communicated less medical information and made fewer reassurance statements to lower literate women in the HBHM relative to the BB group (p<.05).

There was a trend toward lower visit satisfaction for women with restricted literacy in HBHM relative to BB group (p<.1); no difference in satisfaction was evident for more literate women.

Conclusions

The HBHM intervention empowered communication of all women and facilitated verbal engagement and relevant disclosure of medical and psychosocial information of women with literacy deficits. Satisfaction, however, tended to be lower for these women.

Keywords: patient activation, prenatal communication, health literacy, Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS)

Introduction

The literacy demands of the medical dialogue are considerable and significant, but as these challenges fall within the relatively unexplored domain of oral literacy, they have been relatively neglected in the exponentially growing literature addressing health literacy.1–2 Nevertheless, it is in this domain that critical issues arise in face-to-face interactions and it is here that frustration with visit communication commonly arises. While many patients face communication challenges, those with restricted literacy are less able to overcome these barriers and are more likely to suffer negative consequences than other patients, including shame and humiliation.2 Patients with literacy deficits relative to more literate patients, rate their medical visits as less participatory and less satisfying in terms of the interpersonal and communication aspects of care.3–5 When faced with communication challenges, women with restricted literacy express powerlessness and passivity in contrast to higher literate women who report employing a variety of pro-active communication strategies.6

Despite the need for work in this area, few studies have directly observed the relationship between restricted literacy and communication dynamics in general medical care7,8 and none have done so in prenatal care. Similarly, recent reviews of interventions for individuals with low health literacy9 and pre-consultation interventions to help patients ask more questions10 have failed to uncover any programs specifically targeting prenatal populations.

The current study was designed to address this gap with the primary aim of developing and evaluating a skills-based intervention to enhance the communication skills of pregnant women with restricted literacy. Because of the attractiveness and flexibility of interactive computer programs to individually tailor educational messages and demonstrations, and the growing use of such programs in communication activation and decision-making studies with general populations, we wondered if this approach would be acceptable and effective with low-literate women within the context of prenatal care.

A report from the Pew Internet Project indicates that it might; over 90% of individuals between the age of 18 and 29 report regularly going on line suggests that the historic digital divide associated with income and education has substantially diminished.11 We were also encouraged to pursue a computer-based approach by the success of a clinic-based computer kiosk promoting household safety behaviors that targeted mothers of young children attending pediatric and emergency department services in our institution. The kiosk program was found to be effective and positively evaluated by women very much like those targeted in our program.12,13

To explore these questions, we conducted a randomized trial comparing the impact of a communication activation skills program presented within an interactive computer platform with a popular month by month written guide to pregnancy on observed visit communication and patient reported satisfaction. We hypothesized that women exposed to the communication activation intervention would experience more patient-centered visits, be more actively engaged in the visit dialogue, use more of the targeted skills, and be more satisfied with their visit than women who received a more traditional prenatal health education session.

Methods

All 27 residents seeing patients in the prenatal outpatient clinics of an academic, inner city hospital, including general obstetrics, high risk and the multiples clinic, were recruited to participate in the study by email invitation from the Residency Director. Participation was voluntary and the clinicians were not offered any incentive to take part in the study.

Women were eligible for the study if they were seeing a participating clinician, spoke English, and planned to deliver their baby at the study hospital. Recruitment was initiated by the clinic receptionist when scheduling a prenatal appointment; women who expressed interest in the study were asked to provide a phone number to be contacted by study staff or were encouraged to talk directly to staff if they were in the clinic on that day. There were also signs posted around the clinic briefly describing the study with contact information.

Women interested in taking part in the study were given additional details about what would be asked of them, including the need to arrive an hour early to their clinic appointment, participation in a 20-minute prenatal educational program, and completion of study questionnaires. They were also told that their medical visit on the day of the study would be audio recorded. Compensation of $65.00 was offered to the women for completion of the study.

Informed consent was obtained from women at the clinic prior to enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The trial protocol is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov.

Once enrolled, women were randomly assigned to the communication activation program or the facilitated review of relevant sections of “Baby Basics: Your Month by Month Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy”.14

At the time of the study, no other prenatal health education material was routinely offered to clinic patients.

The prenatal visit that followed enrollment was audio recorded and the women and clinicians completed immediate post-visit questionnaires. All visits occurred between June 2010 and January 2011.

Healthy Babies and Healthy Moms (HBHM) Program

HBHM is a 20-minute communication skills-based computer program based on key social learning principles15 designed to empower women to more actively and productively engage in the medical dialogue of their prenatal visits by asking questions, expressing concerns and worries, brainstorming and problem solving pregnancy-related challenges and actively participating in medically-related decision making. The program repeatedly reinforced the message that the best source of prenatal information for a pregnant woman is her doctor; consequently, the program did not provide medical information or advice.

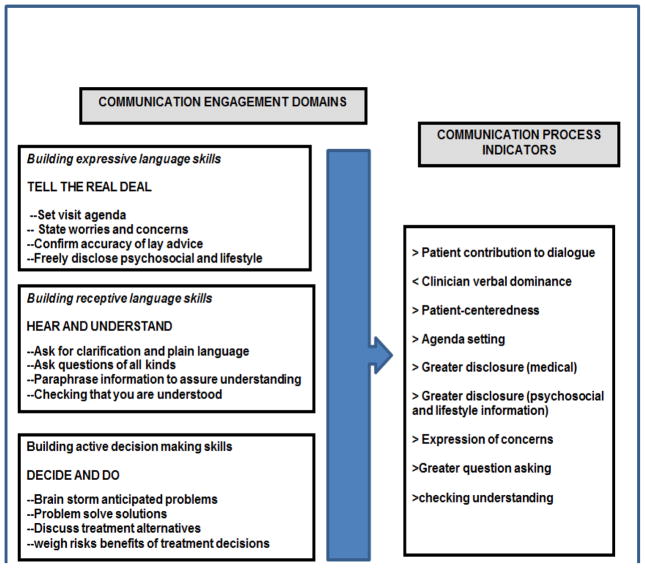

The program organized patient communication behaviors into three thematic domains associated with specified skills hypothesized to impact visit communication processes, as illustrated in Figure 1. The first domain “Tell the Real Deal” was designed to build capacity in expressive language and facilitate patient disclosure of concerns and expectations by encouraging the setting of a visit agenda, disclosing worries and concerns, and sharing psychosocial and lifestyle information. The second domain “Hear and Understand” focused on receptive language skills encouraging questions, asking for plain language explanations of complex information and checking that the doctor understood patient disclosed information. The third domain, “Decide and Do”, focused on increasing patient engagement in medical decision making by encouraging women to weigh decision alternatives by discussing risks and benefits, anticipate problems in adhering to treatment recommendations and brainstorm solutions to anticipated problems.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Study Intervention

Key learning principles guided the intervention design including vicarious modeling, visualization, mental rehearsal, and reinforcement, as described below:

Vicarious Modeling

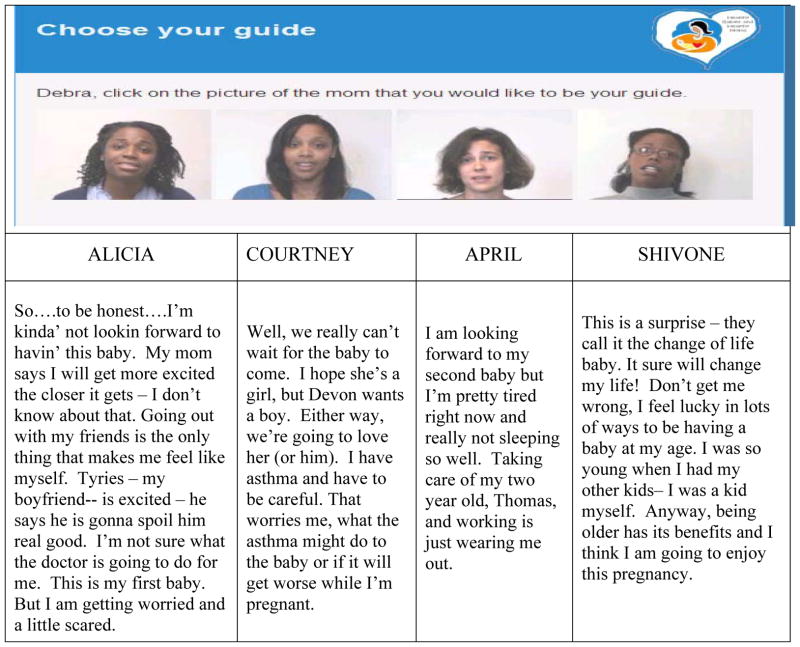

Videos of four women of varying ages and race (three African American and one White) briefly (less than 90 seconds) conveyed their unique story in an engaging way that related challenges and concerns, as well as excitement and positive aspirations for a healthy pregnancy and baby. The narratives and photos of the women as they appeared in the program are displayed in Figure 2. In addition, an African American “grandmotherly” narrator helped women navigate the program by introducing each of the four role models and directing them to choose one as her guide.

Figure 2.

Character Summary of Skill Role Models

Visualization

Targeted skills were demonstrated in short (30–40 second) video segments simulating their use during a prenatal visit. Two skill examples were given by each guide for each skill. While the chosen guide became the default role model, women were repeatedly encouraged to “click” on the photo of the other guides to see how they used the targeted skills.

Mental Rehearsal

After each set of skills were reviewed, the narrator reminded women to think about how they would adapt the skills in their upcoming visit to discuss their own situation and concerns, expectations, questions and treatment options with their doctor.

Reinforcement

At the completion of the program, women received a printed summary of the skill clips they viewed personalized with their first name. The printout included spaces for them to note their own visit agenda, concerns and questions and a message encouraging them to use the summary sheet during their upcoming prenatal visit.

Baby Basics (BB) Prenatal Guide

The comparator in this study was a face-to-face educational session with a study research assistant immediately prior to the scheduled visit during which personally relevant pregnancy related information was reviewed in the Baby Basics prenatal guide. The guide presents information and colorful illustrations in a spiral bound volume that is organized by month of pregnancy and includes gestation-specific information about the growing fetus, the mother’s changing body, health tips related to pregnancy including diet, exercise, and general lifestyle issues, and first-person stories from women and their families facing common struggles. Each section concludes with a summary page to record thoughts, concerns, observations, and questions.

Individual sessions were begun by asking women how far along they were in their pregnancy and opening the book to the chapter designated for the appropriate month of pregnancy. The review was personalized and guided by the woman’s interest and typically took 20 minutes.

Women were given the book as a gift from the project at the end of the session and were encouraged to use it in their visits. Women assigned to the HBHM intervention were also given the book after completing their visit and post-visit questionnaire.

Sources of Data

Three sources of data were used in the study, as described below:

1. Medical Record Data

Gestational age was estimated by calculating the time interval between the visit date and date of delivery derived from the medical record. The number of clinic visits made prior to enrollment was also extracted from the medical chart.

2. Patient post-visit Questionnaire

Post visit patient assessments included a health literacy screen and a measure of visit satisfaction as follows:

Health Literacy

An 8-item health literacy screener (scale range of 0–8) was used that is specific to the prenatal context, the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Genetics (REAL-G).16 The REAL-G has been validated against the widely used Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine(REALM) and found to be predictive of information recall. Scores on the REAL-G below 4 are indicative of literacy skills equivalent to 5th grade or less, a score between 4 and 7 indicates literacy levels equivalent to 6th through 8th grade, and a score of 8 indicates a literacy equivalent that is greater than 8th grade.

Satisfaction

An 8-item visit satisfaction measure (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.89) was used to reflect interpersonal satisfaction (5-point scale ranging from poor (1) to excellent (5)).

3. Visit Audio Recordings

The prenatal visit audio recordings were coded with the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS). The RIAS is a widely used system for characterizing medical dialogue and has well-established reliability and predictive validity.17 The unit of analysis is a statement conveying a complete thought that may be communicated as a single word, simple sentence, or a clause in complex sentence. Statements are coded directly from recordings without transcription and assigned to one of 37 patient and clinician mutually exclusive and exhaustive code categories. The RIAS code categories address biomedically-focused behaviors, psychosocial and lifestyle exchange, facilitation, emotional responsiveness and orientation.

Structural measures of visit communication include visit duration (minutes), the sum of all patient and clinician statements as an indication of total dialogue, and a measure of clinician verbal dominance constructed as the ratio of all clinician to patient statements. As in a number of RIAS-based studies patient-centered communication was operationalized as a ratio reflecting the psychosocial and socioemotional relative to the biomedical focus of the visit dialogue. Specifically, the numerator consists of patient psychosocial and lifestyle disclosure, all patient questions and emotional statements plus the clinician’s psychosocial-related questions, psychosocial and lifestyle information and counseling and facilitation statements. The denominator consists of the sum of clinician medical questions, clinician orientations, and both patient and clinician biomedical information. 18–22

RIAS coders also rated the emotional tone of the patient and the clinician across multiple affective dimensions: (dominance, warmth, engagement, respectfulness (patient and clinician), depressed mood, distress (patient only), hurried (clinician only) on a 5-point scale (low-high)).

The two RIAS coders were not aware of study hypotheses or intervention status. A random 10% sample of audiotapes was drawn throughout the coding period for double coding to establish inter-coder reliability. Pearson correlation coefficients averaged .90 across clinician categories and .91 for patient categories. Reliability for the ratings of emotional tone was calculated as agreement within 1 scale point and these averaged 98% (range 92 – 100%) for both patient and clinician.

Statistical analysis and approach

Simple descriptive analysis was used to characterize study participants. Differences between groups were analyzed using SPSS version 22, generalized linear (GLIN) models and generalized estimating equations (GEE) to adjust for the nesting of patients within physicians. An exchangeable correlation structure was assumed using robust estimation which is likely to yield more accurate or valid coefficient estimates even if the the correlation structure is misspecified.23 Covariates in all communication analysis included gestation at the recorded visit and visit length. Stratified literacy analysis used the REAL-G score dichotomized to reflect literacy deficits (literacy at or below 8th grade level) vs adequate literacy (greater than 8th grade level).

Results

Clinician Participants

Eighteen of 27 program residents (67%) agreed to participate in the study. Five of these residents enrolled patients during an early baseline phase of the study (June 2009 through December 2009) but completed their residency by the time the intervention trial ran one year later (June 2010 through January 2011). One resident did not enroll any baseline patients but did enroll patients during the trial. Consequently, 14 of the originally consented 18 residents contributed patients during the trial. In addition, a NP and 2 attending physicians participated in the trial. The average number of women seen by each clinician was 4.7 (range: 1 to 18); the NP contributed 18 recorded visits and the attending physicians contributed 2 each.

All 17 clinicians were female, averaging 29.1 years of age (range 26 to 35). They were 59% white, 29% African American and 12% Asian.

Patient Participants

As displayed in Table 1, 83 women participated in the trial. The women averaged 24 years of age (range 16 to 44; median 22; mode 20) and were predominantly African American (80%). One-third of women (34%) failed to complete high school and two-thirds scored at or below 8th grade level on the health literacy screening test. On average, women were 26 weeks pregnant at the index visit (range 11 – 39 weeks) and had made 5 clinic visits prior to enrollment in the study (range 0–17). There were no significant differences between the intervention groups on any of these measures.

Table 1.

Description of Study Participants

| Baby Basics | Healthy Babies Healthy Moms | |

|---|---|---|

| (N=43) | (N=40) | |

| Average Age (range) | 23.0 (16–38) | 24.6 (18–44) |

| Number of prenatal visits prior to index (95% CI) | 4.6 (0 – 14) | 5.5 (0 – 17) |

| Weeks pregnant at index visit (95% CI) | 25.1 (11.4 – 37.8) | 26.8 (12.6 – 39.1) |

| Average literacy score (SD) | 5.0 (2.8) | 5.6 (2.8) |

| Number of items correct | ||

| <4 | 13 (31%) | 7 (18%) |

| 4–7 | 15 (36%) | 17 (45%) |

| 8 | 14 (33%) | 14 (37%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | 34 (81%) | 31 (79%) |

| White | 6 (14%) | 5 (13%) |

| Other (Asian, American Indian, mixed race) | 2 (5%) | 3 (8%) |

| Education | ||

| <HS | 16 (38%) | 12 (31%) |

| HS/GED | 13 (31%) | 17 (43%) |

| Post-Secondary | 13 (31%) | 10 (26%) |

The majority of women (87%) were recruited from a single general obstetrics clinic with a handful coming from specialty clinics staffed by study clinicians.

Verbal Communication

Table 2 displays intervention differences for targeted categories of patient communication stratified by patient literacy. There were no significant differences in the length of the obstetrical visit between intervention groups or by literacy level. However, women exposed to the HBHM intervention were more verbally active during the visit than those in the BB group; the difference in number of patient statements was statistically significant for women with literacy deficits (p<.05) and showed a consistent trend for women with adequate literacy (p<.10).

Table 2.

Intervention Effects on Patient Communication Stratified by Patient Literacy

| Baby Basics | Healthy Babies Healthy Moms | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean scores (95%CI) | Mean scores (95%CI) | |

| (N=43) | (N=40) | |

| Visit length in minutes | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 22.9 (17.4 – 28.4) | 23.7 (18.9 – 28.6) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 22.4 (18.3 – 26.5) | 21.4 (17.4 – 25.5) |

| Total Patient Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 104 (93 – 115) | 129 (112 – 146)* |

| >8th grade equivalent | 136 (113 – 158) | 172 (137 – 207)+ |

| Questions | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 4.3 (2.8 – 5.8) | 5.3 (4.1 – 6.5) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 6.2 (4.3 – 8.1) | 5.6 (4.0 – 7.2) |

| Medical Information Disclosure | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 35.2 (27.5 – 42.9) | 44.9 (38.5 – 51.3)* |

| >8th grade equivalent | 40.0 (31.3 – 48.8) | 48.8 (27.5 – 70.1) |

| Psychosocial/Lifestyle Information Disclosure | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 12.3 (10.0 – 14.6) | 16.4 (14.1 – 18.8)* |

| >8th grade equivalent | 12.0 (8.7 – 15.4) | 19.0 (11.5 – 26.4)+ |

| Concern Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 3.6 (1.9 – 5.3) | 7.4 (5.3 – 9.5)* |

| >8th grade equivalent | 3.9 (2.4 – 5.3) | 9.9 (4.8 – 15.0)* |

| Approval Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 1.3 (1.1 – 1.6) | 0.8 (0.5 – 1.1)** |

| >8th grade equivalent | 2.5 (1.7 – 3.2) | 1.5 (1.1 – 1.9)** |

| Orientation Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 0.8 (0.4 – 1.12) | 1.3 (1.0 – 1.6)** |

| >8th grade equivalent | 0.7 (0.4 – 1.01) | 1.2 (0.7 – 1.7)* |

| Global Ratings of Dominance | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 3.0 (2.7 – 3.3) | 3.4 (3.3 – 3.6)** |

| >8th grade equivalent | 3.5 (3.2 – 3.7) | 3.7 (3.5 – 4.0) |

Adjusted for nesting of patients within provider, gestation and visit length

p<.1;

p<.05;

p<.01

Differences in targeted communication skills used by HBHM relative to BB group women, regardless of literacy level, include significantly more patient expression of concerns, fewer approval statements and more orientation statements indicative of setting visit goals and agenda. Lower literate women exposed to the HBHM intervention also disclosed significantly more medical and psychosocial/lifestyle information to their clinician and had higher global ratings of dominance than lower literate women exposed to the BB intervention.

While clinician communication was not specifically targeted, differences between intervention groups were evident in several categories (Table 3). Clinicians used significantly more, almost twice as many cues of interest indicative of attentive listening with women in the HBHM compared to the BB group, regardless of literacy level. In addition, when with lower literate women in the HBHM relative to the BB group, clinicians provided significantly less medical information (58 vs 71 statements) and made fewer reassurance statements (12 vs 18); no statistically significant differences were evident in these categories for more literate women. Clinicians also made significantly fewer concern (6 vs 8) and orientation (18.2 vs 24.8) statements when with more literate women in the HBHM relative to the BB group.

Table 3.

Intervention effects on Clinician Communication Stratified by Patient Literacy

| Baby Basics | Healthy Babies Health Moms | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean scores (95%CI) | Mean scores (95%CI) | |

| (N=43) | (N=40) | |

| Total Physician Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 275 (235 – 315) | 244 (216 – 272) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 277 (245 – 310) | 258 (212 – 304) |

| All Questions | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 32.7 (23.4 – 42.0) | 31.2 (25.6 – 36.7) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 25.4 (20.6 – 30.2) | 26.1 (17.5 – 34.6) |

| Medical Information & Counseling | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 71.3 (58.2 – 84.5) | 58.0 (46.2 – 69.8)* |

| >8th grade equivalent | 90.8 (71.8 – 109.8) | 71.9 (49.7 – 94.1) |

| Psychosocial/Lifestyle Information | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 9.7 (6.36 – 13.0) | 10.7 (7.7 – 13.6) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 12.5 (8.7 – 16.3) | 13.0 (3.1 – 22.9) |

| Facilitation Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 47.7 (39.3 – 56.1) | 49.1 (40.4 – 57.9) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 38.9 (31.2 – 46.5) | 44.2 (34.4 – 54.1) |

| Cues of Interest | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 5.6 (3.2 – 8.1) | 13.2 (10.3 – 16.1)*** |

| >8th grade equivalent | 5.8 (2.5 – 9.1) | 13.4 (9.4 – 17.5)* |

| Reassurance Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 17.8 (12.1 – 23.5) | 12.1 (9.5 – 14.7)* |

| >8th grade equivalent | 17.0 (11.4 – 22.6) | 12.9 (8.9 – 17.0) |

| Concern Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 6.9 (4.5 – 9.3) | 6.2 (4.8 – 7.6) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 8.5 (6.0 – 10.9) | 6.3 (4.6 – 8.1)* |

| Approval Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 5.6 (3.2 – 8.0) | 3.3 (1.9 – 4.7)+ |

| >8th grade equivalent | 3.0 (1.7 – 4.4) | 4.2 (3.2 – 5.1)+ |

| Orientation Statements | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 28.9 (22.8 – 35.0) | 26.9 (21.2 – 32.5) |

| >8th grade equivalent | 24.8 (18.8 – 30.7) | 18.2 (12.0 – 24.4)* |

| Ratio of Clinician/Patient Talk | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 2.8 (2.2 – 3.3) | 2.2 (1.9 – 2.5)+ |

| >8th grade equivalent | 2.6 (2.3 – 3.0) | 1.8 (1.5 – 2.1)* |

| Patient-centeredness | ||

| ≤=8th grade equivalent | 0.49 (0.43 – 0.55) | 0.58 (0.52 – 0.64)+ |

| >8th grade equivalent | 0.46 (0.40 – 0.52) | 0.59 (0.52 – 0.65)* |

Adjusted for nesting of patients within provider, gestation and visit length

p<.1;

p<.05;

p<.01

Overall, HBHM relative to BB visits were characterized by a more patient-centered communication pattern and lower levels of clinician verbal dominance; differences in both of these measures were statistically significant for women with adequate literacy (p<.05) and suggestive for women with literacy deficits (p<.1).

Patient Post Visit Satisfaction

Visit satisfaction of women with restricted literacy tended to be lower for those in HBHM relative to BB group visits (4.0 (95% CI: 3.9 – 4.2) vs 4.2 (95% CI: 4.1 – 4.3); p<.1). The group difference in visit satisfaction was not evident for more literate women (4.3 vs 4.2 (95% CI: 4.1–4.5); p >.5).

Discussion

Our findings support the effectiveness of the HBHM intervention relative to BB in enhancing medical visit communication for women regardless of literacy deficits without increasing visit length. Women randomized to the HBHM intervention experienced visits that were more patient-centered and less verbally dominated by clinicians; women were more verbally active and demonstrated increased use of targeted communication skills, including the expression of concerns and use of orientation statements consistent with agenda setting. HBHM group women also tended to respond to their clinicians in a somewhat less unconditionally accepting manner (marked by fewer approval statements) than women exposed to the BB intervention.

Further, findings reflect an especially positive pattern of HBHM intervention effects for women with literacy deficits. Lower literate women in the HBHM group disclosed more medical, psychosocial and lifestyle information to their clinicians than women in the BB group and they were rated by coders as sounding more dominant throughout the visit.

Several differences in clinician communication across intervention groups are also of note. Clinicians used more cues of interest with all women exposed to the HBHM relative to the BB intervention but they also made fewer reassurance statements and gave less medical information to lower literate women in the HBHM compared with the BB group. There is some precedent in considering these findings in a positive light. A study designed to enhance communication skills of pediatric residents reported a significant reduction in their high use of reassurance statements that was interpreted as a positive indication of training success. This interpretation was bolstered by the observation that the high frequency of reassurance statements prior to training appeared perfunctory and largely ineffective in addressing patient concerns and that the reduction was offset by a wider emotional repertoire after training.24 We similarly conclude that the relative reduction in clinician reassurance with low literate women in the HBHM compared with BB intervention (12.1 vs 17.8, statements per visit respectively) may similarly mark a more nuanced response to patient stated concerns.

We reported that clinicians conveyed significantly less medical information (about 20% less) to lower literate patients in HBHM relative to BB visits and also found that these women disclosed significantly more medical and psychosocial/lifestyle information to their clinicians. Genetic counseling sessions dominated by the provision of medical information have been associated with indicators of high oral literacy demand; these visits use more technical terms, general language complexity, fewer and more dense speaking turns, and low dialogue interactivity.25 Furthermore, subjects with restricted literacy who viewed high literacy demand session videotapes learned significantly less genetic information than those who viewed lower literacy demand sessions.26 Additional insight into oral literacy demand is provided by another study; simulated primary care visits characterized by less dense speaking turns and higher interactivity were significantly related to the RIAS-scored measure of patient centeredness, as well as positive ratings of affective demeanor, interpersonal satisfaction and collaborative decision-making by the simulated patient.27

Clinician communication associated with lower literacy demand in the above cited studies includes cues of interest, lowered verbal dominance as an indication of listening more and talking less, and higher levels of overall patient-centeredness – exactly what was found to be the case in the current study.

We suggest that when taken together, the contrasts in communication found in our study represent a fundamental difference in the interactive dynamics of the two groups; BB visits were more informationally dense and clinician dominated consistent with markers of high oral literacy burden, while HBHM visits were characterized by patient-centeredness, patient-engagement and markers of lower oral literacy burden.

There are two areas in which we failed to find expected group differences: patient question asking and patient satisfaction. We speculate that use of the Baby Basics prenatal guide as the comparator may have diminished group differences in regard to both of these measures. In respect to question asking, each Baby Basics chapter ends with a page designated for women to write down and ask questions to their doctor. Consequently, the question prompt was reinforced by the study research assistant as part of the intervention, thereby increasing patient questions and diminishing intervention differences in this category of communication.

The finding of a trend toward lower satisfaction among HBHM group women with literacy deficits relative to their BB counterparts was not expected, although the result is reminiscent of a finding reported from the first randomized communication activation trial undertaken with an inner-city chronic disease patient population.28 In that study, an activation intervention administered immediately prior to a medical visit was successful in increasing patient question asking and verbal activity during the subsequent medical visit but it was also associated with higher ratings of patient anxiety and lower levels of post-visit satisfaction. These results were interpreted as a negative consequence of undertaking an unfamiliar and challenging task. Interestingly, a 6-month follow-up found that patients exposed to the activation intervention kept significantly more scheduled appointments than comparison group patients suggesting that the outcomes of anxiety and lowered satisfaction may have been transitory.

We do not know if this is the case for the women in the current study and future research is planned to follow study changes in satisfaction subsequent to an activation intervention over time.

There are several limitations of the current study. First, the study sample is small and subject to self-selection bias. We do not know how study patients may have differed from women who declined participation. We do know that among women interested enough to speak with research staff about the study, 35 (30%) were not enrolled; 6 declined participation after hearing about the study but the remainder were ineligible because they were scheduled with a non-consented physician, delivered or miscarried prior to their study appointment or missed their study appointment. Despite the possibility of patient self-selection bias, study participants appear to be generally representative of the clinic population and the urban catchment area of the Hospital in terms of race/ethnicity and literacy. Moreover, randomization to intervention groups occurred after women were consented and the groups did not differ on basic demographic characteristics.

Self-selection bias may also have affected resident participation in the study, skewing participation toward less experienced residents. As noted earlier, 18 of 27 residents agreed to participate in the study; of the 9 who declined, 3 were in their first or second year of residency (of 15 eligible residents) and 6 (of 12 eligible residents) were in the final year of their residency.

While the study was sufficiently powered to examine overall intervention group differences, the stratification analysis by patient literacy was under-powered in that there is twice the number of women in the study with literacy deficits than adequate literacy. We believe that the results are worthwhile and informative but should be interpreted with caution. This caveat also applies to limited study generalizability to patients receiving care primarily from residents in an urban, academic clinic setting.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that we were successful in designing a patient activation intervention that women with restricted literacy were able to use to change the nature of their prenatal visit communication in a meaningful and positive way. The intervention also appeared to benefit women without literacy deficits in improving their communication in consequential ways.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from NICHD, RO1 HD050437, Amelioration of Literacy Deficits in Prenatal Care.

The authors acknowledge the help of the women and clinicians who participated in our study. We are especially indebted to Rita Johnson for her help in patient recruitment and for her role as the study’s kindly grandmother, in all ways. We also appreciate the contribution of Jayesh Jariwala and the team at Applied Control Engineering Inc., for software development.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare, September 29–October 2, 2013, Montreal, Canada, sponsored by the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare.

Contributor Information

Debra L. Roter, Email: droter1@jhu.edu, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N. Broadway, Baltimore, MD, 21205 USA; telephone 410 955 6498; fax 410 955 7241.

Lori H. Erby, Email: lori.erby@nih.gov, Social and Behavioral Research Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Rockville Maryland.

Rajiv N. Rimal, Email: rrimal@email.gwu.edu, Department of Prevention and Community Health, George Washington University, District of Columbia.

Katherine C. Smith, Email: ksmit103@jhu.edu, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Baltimore Maryland.

Susan Larson, Email: slarson@jhu.edu, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Baltimore Maryland.

Ian M. Bennett, Email: Ian.Bennett@uphs.upenn.edu, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Pennsylvania.

Katie Washington Cole, Email: katiewashington@jhu.edu, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Baltimore Maryland.

Yue Guan, Email: yguan6@jhu.edu, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Baltimore Maryland.

Matthew Molloy, Email: matthew.molloy10@gmail.com, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore Maryland.

Jessica Bienstock, Email: jbienst@jhmi.edu, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore Maryland.

References

- 1.Kindig D, Panzer A, Nielsen-Bohlman L, Hamlin B, editors. Health literacy: Prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parikh NS, Parker RM, Nurss JR, Baker DW, Williams MV. Shame and health literacy: the unspoken connection. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:33–9. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roter D. Health Literacy and the Patient Provider Relationship. In: Schwartzberg J, Van Geest J, Wang C, Gazmararian J, Parker R, Roter D, Rudd R, Schillinger D, editors. Understanding Health Literacy: Implications for Medicine and Public Health. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2004. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper LA, Beach MC, Clever SL. Participatory decision-making in the medical encounter and its relationship to patient literacy. In: Schwartzberg J, Van Geest J, Wang C, Gazmararian J, Parker R, Roter D, Rudd R, Schillinger D, editors. Understanding Health Literacy: Implications for Medicine and Public Health. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2004. pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Pitkin K, Parikh NS, Coates W, Imara M. The health care experience of patients with low literacy. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:329–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.6.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett IM, Switzer J, Barg F, Aguirre A, Evans K. Breaking it down: Patient-provider communication and prenatal care utilization among African American women with low literacy. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:334–40. doi: 10.1370/afm.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aboumatar HJ1, Carson KA, Beach MC, Roter DL, Cooper LA. The impact of health literacy on desire for participation in healthcare, medical visit communication, and patient reported outcomes among patients with hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1469–76. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schillinger D1, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004 Mar;52(3):315–23. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheridan SL1, Halpern DJ, Viera AJ, Berkman ND, Donahue KE, Crotty K. Interventions for individuals with low health literacy: a systematic review. J Health Commun. 2011;16:30–54. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinnersley P1, Edwards A, Hood K, Ryan R, Prout H, Cadbury N, MacBeth F, Butow P, Butler C. Interventions before consultations to help patients address their information needs by encouraging question asking: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;337:a485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox. 2011 Feb 1; http://pewinternet.org/reports/2011/healthTopics.aspx.

- 12.McDonald EM, Solomon B, Shields W, Serwint JR, Jacobsen H, Weaver NL, Krueter M, Gielen AC. Evaluation of kiosk-based tailoring to promote household safety behaviors in an urban pediatric primary care practice. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;58:168–181. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shields WC1, McDonald EM, McKenzie L, Wang MC, Walker AR, Gielen AC. Using the pediatric emergency department to deliver tailored safety messages: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:628–34. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828e9cd2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baby Basics: Your Month by Month Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy. The What to Expect Foundation; NY, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erby LAH, Roter D, Larson S, Cho J. The rapid estimate of adult literacy in genetics (REAL-G): A means to assess literacy deficits in the context of genetics. Am J Med Genet. 2008;146:174–181. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roter DL, Larson S. The Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS): Utility and Flexibility for Analysis of Medical Interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helitzer DL, LaNoue MD, Wilson B, Urquieta de Hernandez B, Warner T, Roter D. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Communication Training with Primary Care Providers to Improve Patient-Centeredness and Health Risk Communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(1):21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alegría M, Roter DL, Valentine A, Chen CN, Li X, Lin J, Rosen D, Lapatin S, Normand SL, Larson S, Shrout PE. Patient-clinician ethnic concordance and communication in mental health intake visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:188–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beach MC, Roter D, Korthuis PT, Epstein RM, Sharp V, Ratanawongsa N, Cohn J, Eggly S, Sankar A, Moore RD, Saha S. A multicenter study of physician mindfulness and health care quality. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:421–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Bone LR, Larson SM, Miller ER, 3rd, Barr MS, Levine DM. A Randomized Trial to Improve Patient-Centered Care and Hypertension Control in Underserved Primary Care Patients. J of Gen Int Med. 2011;26:1297–304. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1794-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, Inui TS. Clinicians’ Implicit Attitudes about Race Influence Medical Visit Communication and Patient Ratings of Interpersonal Care. AJPH. 2012;102:979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.IBM SPSS statistics version 22. Copyright IBM Corporation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roter D, Larson S, Shinitzky H, Chernoff R, Serwint JR, Adamo G, Wissow L. Use of an innovative video feedback technique to enhance communication skills training. Med Ed. 2004;38:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2004.01754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roter DL, Erby LH, Larson S. Assessing oral literacy demand in genetic counseling dialogue: a preliminary test of a conceptual framework. Soc Sci & Med. 2007;865:1442–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roter DL, Erby LH, Larson S, Ellington L. Oral literacy demand of prenatal genetic counseling dialogue: Predictors of learning. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):392–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roter DL, Larson SM, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Interactive and evaluative correlates of dialogue sequence: a simulation study applying the RIAS to turn taking structures. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roter DL. Patient Participation in the Patient-Provider Interaction: The Effects of Patient Question Asking on the Quality of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Compliance. Health Education Monographs. 1977;50:281–315. doi: 10.1177/109019817700500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]