Abstract

In an environment with large portion sizes, allowing consumers more control over their portion selection could moderate the effects on energy intake. We tested whether having subjects choose a portion from several options influenced the amount selected or consumed when all portion sizes were systematically increased. In a crossover design, 24 women and 26 men ate lunch in the lab once a week for 3 weeks. At each meal, subjects chose a portion of macaroni and cheese from a set of 3 portion options and consumed it ad libitum. Across 3 conditions, portion sizes in the set were increased; the order of the conditions was counterbalanced across subjects. For women the portion sets by weight (g) were 300/375/450, 375/450/525, and 450/525/600; for men the portions were 33% larger. The results showed that increasing the size of available portions did not significantly affect the relative size selected; across all portion sets, subjects chose the smallest available portion at 59% of meals, the medium at 27%, and the largest at 15%. The size of portions offered did, however, influence meal intake (P<0.0001). Mean intake (±SEM) was 16% greater when the largest set was offered (661±34 kcal) than when the medium and smallest sets were offered (both 568±18 kcal). These results suggest that portions are selected in relation to the other available options, and confirm the robust effect of portion size on intake. Although presenting a choice of portions can allow selection of smaller amounts, the sizes offered are a critical determinant of energy intake. Thus, the availability of choices could help to moderate intake if the portions offered are within an appropriate range for energy needs.

Keywords: Portion size, Portion selection, Energy intake, Eating environment

Introduction

The portion size of food is an environmental factor with one of the strongest and most consistent influences on intake. Numerous studies show that serving larger portions leads to increased consumption of a variety of foods and in many settings (Rolls, 2014; English, Lasschuijt & Keller, 2015; Benton, 2014). In an environment where large portions are prevalent (Young & Nestle, 2012), it is important to identify effective strategies to counter their influence on consumption. One potential strategy is to allow consumers more control by offering a range of portion sizes from which to choose (Vermeer, Steenhuis, & Seidell, 2010). The current study tested how both selection and intake from a range of portion sizes were affected when the size of all available portions was increased.

A previous study investigated whether allowing subjects greater control over the amount of food on their plates attenuated the effect of portion size on intake (Rolls, Morris & Roe, 2002). As the amount of the pasta dish was increased across meals, some subjects were served a pre-plated portion and other subjects served their own portion from a serving dish onto the plate. The food used in that study was macaroni and cheese, which is amorphous in shape; such foods are commonly used in portion size studies rather than foods served in discrete pieces, which may encourage consumption of whole units (Geier, Rozin, & Doros, 2006). It was found that the influence of portion size on intake was not affected by whether the amount of food on the plate was determined by the subject or the researcher; for both groups, increases in the amount of available food led to increased intake. It is possible that allowing subjects to choose the size of their meal from several pre-plated options, presented at the same time, would moderate intake when portion sizes are increased (Vermeer, Steenhuis, & Seidell, 2009; Vermeer, Steenhuis & Seidell, 2010). In most previous studies, only one portion size of each food was offered at a meal. This may have led subjects to determine intake based on the amount of food available, either due to habit (Rolls et al., 2002) or a perception that the amount offered was appropriate (Herman, Polivy, Pliner, & Vartanian, 2015). Offering subjects a range of portions could modify the portion size effect by providing visual cues that help consumers assess the amount of food most appropriate to meet their particular needs (Vermeer, Steenhuis & Seidell, 2010) or to match their personal norms (Lewis, Forwood, Ahern, Verlaers, Robinson, Higgs & Jebb, 2015a).

The effect of offering a choice of portion sizes on the amount of food selected has been tested in a few studies, but only in conjunction with other factors such as cost (Vermeer, Steenhuis, Leeuwis, Heymans, & Seidell, 2011; Vermeer, Alting, Steenhuis & Seidell, 2010) and portion size labeling (Vermeer, Steenhuis, Leeuwis, Bos, de Boer, & Seidell, 2010). Moreover, the effect of portion selection on intake was not measured. Given the current eating environment (Young & Nestle, 2012), it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of offering portion options in moderating intake when the size of all available portions is increasing. Thus, we tested how offering a choice of portions of macaroni and cheese, with those options varying in size on different occasions, would affect portion selection and intake at a meal. We hypothesized that subjects would choose their portion in relation to the sizes of the other available portions, rather than by the absolute magnitude. Consequently, when the sizes of all available portions were increased, subjects would select and consume greater amounts of food. Alternatively, as the size of the portion options increased, subjects might notice this difference and choose relatively smaller portions. In an environment of increasing amounts of food, assessing the response to portion options will help evaluate a potential strategy to counter the effect of large portions on energy intake.

Methods

Subject recruitment and characteristics

Participants were recruited through advertisements placed in local and university newspapers and fliers posted on campus. Potential subjects were interviewed by telephone to determine whether they met preliminary inclusion criteria: 18–45 years old, regularly ate three meals per day, did not smoke, were not athletes in training, did not report any food allergies or restrictions, did not take any medications affecting appetite, and were willing to eat the food served at test meals. Individuals who met these criteria came to the laboratory to have their height and weight measured and to complete three questionnaires: the Zung Self-rating Scale to assess symptoms of depression (Zung, 1986), the Eating Attitudes Test to assess disordered attitudes toward eating or food (Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, & Garfinkel, 1982), and the Eating Inventory to assess dietary restraint, disinhibition, and tendency toward hunger (Stunkard & Messick, 1985). Potential subjects were only enrolled in the study if their body mass index was 18–35 kg/m2 and they scored < 40 on the Zung Scale and < 19 on the Eating Attitudes Test.

A power analysis estimated that 42 subjects would be needed to detect a 50 g difference in intake between sets of portion options at 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Fifty subjects were enrolled and all of them completed the study; subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. Twenty-three subjects (46%) were overweight and two (4%) were obese. Subjects completed signed consent and were financially compensated for their participation in the study. All procedures were approved by the Office for Research Protections of The Pennsylvania State University.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Characteristic | Women (n = 24) | Men (n = 26) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM | Range | Mean ± SEM | Range | |

| Age (y) | 28.1 ± 1.6 | 19.3 – 45.8 | 25.2 ± 1.0 | 17.9 – 36.0 |

| Height (m) | 1.64 ± 0.01 | 1.51 – 1.80 | 1.77 ± 0.01a | 1.63 – 1.93 |

| Weight (kg) | 65.6 ± 1.8 | 51.6 – 83.6 | 80.2 ± 2.0a | 64.0 – 112.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 0.6 | 19.1 – 29.1 | 25.5 ± 0.6 | 20.9 – 34.0 |

| Estimated energy expenditure (kJ/d)A | 9331 ± 155 | 8309 – 11113 | 12093 ± 151 | 10584 – 13833 |

| Estimated energy expenditure (kcal/d)A | 2230 ± 37 | 1986 – 2656 | 2890 ± 36 | 2530 – 3306 |

| Eating Attitudes Test scoreB | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 0 – 9 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0 – 15 |

| Dietary restraint scoreC | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 0 – 14 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 0 – 18 |

| Disinhibition scoreC | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 2 – 10 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 1 – 11 |

| Tendency to hunger scoreC | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 0 – 13 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 0 – 10 |

Energy expenditure was estimated from sex, age, height, weight, and activity level (Institute of Medicine, 2002)

Range of possible values 0 – 78 (Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, & Garfinkel, 1982)

Range of possible values for scores on the Eating Inventory: dietary restraint 0 – 21, disinhibition 0 – 16, hunger 0 – 14 (Stunkard & Messick, 1985)

Mean value for women is significantly different from mean value for men (P < 0.0001)

Experimental design

This study used a crossover design with repeated measures; subjects came to the laboratory to eat lunch once a week for three weeks. At each meal, subjects were shown a set of three portion sizes of food, selected one for their lunch, and consumed it ad libitum. In this experiment, a “set” is defined as three plates of the test food, with each plate containing a different weight of food. Across the three meals, the portion sizes offered in the sets were varied, from Set 1 with the smallest options to Set 3 with the largest options (Table 2). The order of presenting the sets of portion sizes across occasions was counterbalanced across subjects. The three portions within each set are identified by their relative portion size (smallest, medium, or largest); this description indicates the size of the portion relative to the other portions in the set, rather than the absolute weight of the portion. In all sets, the portion sizes offered to women were 75% of the portion sizes offered to men.

Table 2.

Portion sizes of macaroni and cheese in each set presented to women and men

| Portion size (g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 24) | Men (n = 26) | |||||

| Relative portion size | Relative portion size | |||||

| Set of portion sizes | Smallest | Medium | Largest | Smallest | Medium | Largest |

| Set 1 | 300 | 375 | 450 | 400 | 500 | 600 |

| Set 2 | 375 | 450 | 525 | 500 | 600 | 700 |

| Set 3 | 450 | 525 | 600 | 600 | 700 | 800 |

Experimental Meals

The test food served at all meals was macaroni and cheese (Kraft Foods Group Inc., Northfield, IL, USA) with an energy density of 6.6 kJ/g [1.6 kcal/g], which was presented on standard dinner plates (diameter 26 cm [10.25 in]). After selecting a portion from the three sizes offered in the set, subjects were seated in a cubicle with the food and 1 L of tap water and were instructed to eat and drink as much as they wanted.

Across the three test meals, subjects were offered each of the three sets of portion sizes shown in Table 2. A total of five different portion sizes were served across the three sets. The smallest portion offered in Set 1 was similar to the mean intake of the same food (300 g for women, 400 g for men) in previous laboratory studies (Rolls et al., 2002; Rolls, Roe, Halverson, & Meengs, 2007). The smallest portion in Set 2 represented a 25% increase in portion size compared to the smallest portion in Set 1, and the smallest portion in Set 3 represented a 50% increase in portion size compared to Set 1. The three portion sizes offered in Set 3 were 150 to 200% of the mean intake of the same food by each sex in previous laboratory studies. The energy content of the five portions ranged from 1980 to 3960 kJ [480 to 960 kcal] for women and 2640 to 5280 kJ [640 to 1280 kcal] for men. This range was similar to that of main dishes of pasta in cheese sauce (1250 to 8410 kJ [300 to 2010 kcal]) served in 13 restaurants, many of which were listed in the most popular U.S. restaurant chains (Nation’s Restaurant News, 2012).

The order of presenting the three sets of portions across test days was counterbalanced within blocks of six subjects, and subjects were randomly assigned one of these orders. In addition, for a given subject, the smallest, medium and largest portions within the set were displayed in different positions (on the left, right, or center) across the three meals, as designated by a Latin square.

At each meal, the test food and water were weighed before being served and the remaining amounts were weighed after the meal to determine the amount consumed to the nearest 0.1 g. Energy intake was calculated from the weight consumed using information from the food manufacturer.

Daily procedures and assessments

Subjects were instructed to keep their food intake and activity level consistent and to refrain from consuming alcohol during the 24 h before each test meal; they kept a brief record of their food intake and activity to encourage compliance. On tests days, subjects were served a standard breakfast which was consumed ad libitum. Following breakfast, they were instructed to refrain from consuming any food or energy-containing beverages until their scheduled lunch time; water could be consumed up to 1 h prior to the test meal. Upon returning to the laboratory for their test meal, participants completed a brief questionnaire asking whether they had felt ill, taken any medications, or consumed any foods or energy-containing beverages since breakfast; subjects who met any of these criteria had their test meal rescheduled.

At each test meal, individual subjects were led to a booth where they were left alone to select a portion to eat for the meal from the set. Subjects were then taken back to their private booth where they ate lunch. Before and after each test meal, subjects rated their hunger, fullness, and prospective consumption using 100-mm visual analog scales (Flint, Raben, Blundell, & Astrup, 2000). For example the question on prospective consumption (“How much food do you think you could eat right now?”) was answered by marking the scale between the left anchor (Nothing at all; recorded as 0) and the right anchor (A large amount; recorded as 100). Before beginning the meal, subjects rated characteristics of the portion they had selected; they tasted a bite of the test food and used 100-mm visual analog scales to rate the pleasantness of taste, the portion size in general, and the size in comparison to their usual portion. The question for portion size in general was “How large is the portion of this food?” (anchored with Not at all large to Extremely large) and the question regarding usual portion size was “How does the size of this serving of food compare to your usual portion?” (anchored with A lot smaller to A lot larger).

After the final experimental meal, subjects completed a discharge questionnaire in which they described any differences they noticed between the meals and they reported their ideas concerning the purpose of the study. In addition, subjects were asked how they decided which plate of food to select each week; they chose the most important reason from eight possible responses including: “I chose the one that was a certain size (small, medium, or large),” “I chose the one that matched my appetite that day,” “I chose that one that looked the most appealing to me,” and “I chose the one that looked closest to the amount I usually eat.”

Data analyses

This experiment used a crossover design, so that subjects served as their own controls. The main outcomes of the study were portion size selection and meal energy intake; secondary outcomes were subject ratings of hunger and satiety and subject ratings of food characteristics. Portion size selection was analyzed using repeated measures ordinal logistic regression to evaluate whether the distribution of the relative portion size chosen (smallest, medium, or largest) was affected by the set of portions offered. In addition, the proportion of subjects who selected the same relative portion size at all meals was compared to that expected by chance using a Z-test for one proportion.

Mean energy intake at the meal, as well as mean portion selected and subject ratings of satiety and food characteristics, were analyzed using a mixed linear model with repeated measures. The fixed factors in the model were the set of portions offered, subject sex, and the study week. A repeated factor was included in the model to account for the correlation among multiple observations on the same subjects. For outcomes with significant effects, the Tukey-Kramer method was used to adjust significance levels for multiple pairwise comparisons between means. Ratings of hunger and satiety measured after the meal were adjusted by including the before-meal rating as a covariate in the model. Analysis of covariance was used to examine the influence of continuous participant characteristics, such as body mass index and questionnaire scores, on the relationship between the set of portion sizes and meal intake. All analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Results were considered significant at P < 0.05; results are reported for logistic regression as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and for mixed linear models as mean ± SEM.

Results

Portion selection

Increasing the size of the set of portions offered to subjects did not affect the relative portion sizes that were selected for the meal. The proportion of subjects who chose the smallest, medium, and largest relative portions in the set did not differ significantly across the sets (Table 3; P = 0.33), nor by sex (P = 0.20), according to ordinal logistic regression analysis. The odds ratio for the comparison of Set 1 with Set 3 was 1.10 (95% CI 0.48 – 2.49) and for the comparison of Set 2 with Set 3 was 1.82 (95% CI 0.78 – 4.29). In particular, when Set 3 (very large portions) was offered, there was no increase in the proportion of subjects who selected the smallest portion offered. Across the sets of portions, subjects chose the smallest of the three available portions at 59% of meals, the medium at 27% of meals, and the largest at 15% of meals. The distribution of relative portion sizes selected by subjects was not significantly affected by whether the portion was displayed on the left, center, or right (P = 0.43).

Table 3.

Frequency of selection of relative portion sizes from each set of portions offered to 50 subjects

| Relative size selected Number of meals (% of meals in the set) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set of portion sizes | Smallest | Medium | Largest | Total |

| Set 1 | 28 (56%) | 14 (28%) | 8 (16%) | 50 (100%) |

| Set 2 | 31 (62%) | 16 (32%) | 3 (6%) | 50 (100%) |

| Set 3 | 29 (58%) | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 50 (100%) |

| Total | 88 (59%) | 40 (27%) | 22 (15%) | 150 (100%) |

Note: The set of portions offered had no significant effect on the distribution of the relative sizes chosen, according to ordinal logistic regression analysis (P = 0.33). Since there was no significant effect of sex on the distribution (P = 0.20), the numbers are presented for women and men combined.

Twenty-one subjects (42%) consistently chose the same relative portion size at all three meals; of these subjects, 18 (36%) always chose the smallest portion, 2 (4%) always chose the medium portion, and 1 (2%) always chose the largest portion. The proportion of subjects who always chose the same relative portion size (42%) differed significantly from that expected by chance (3 out of 27, or 11%), according to a Z-test for one proportion (P < 0.0001). Thus, although the size of the portions in the set did not have a significant effect on the relative size of the chosen portion, neither was the selection of portions random; many subjects consistently chose their portion in relation to the other sizes available within the set.

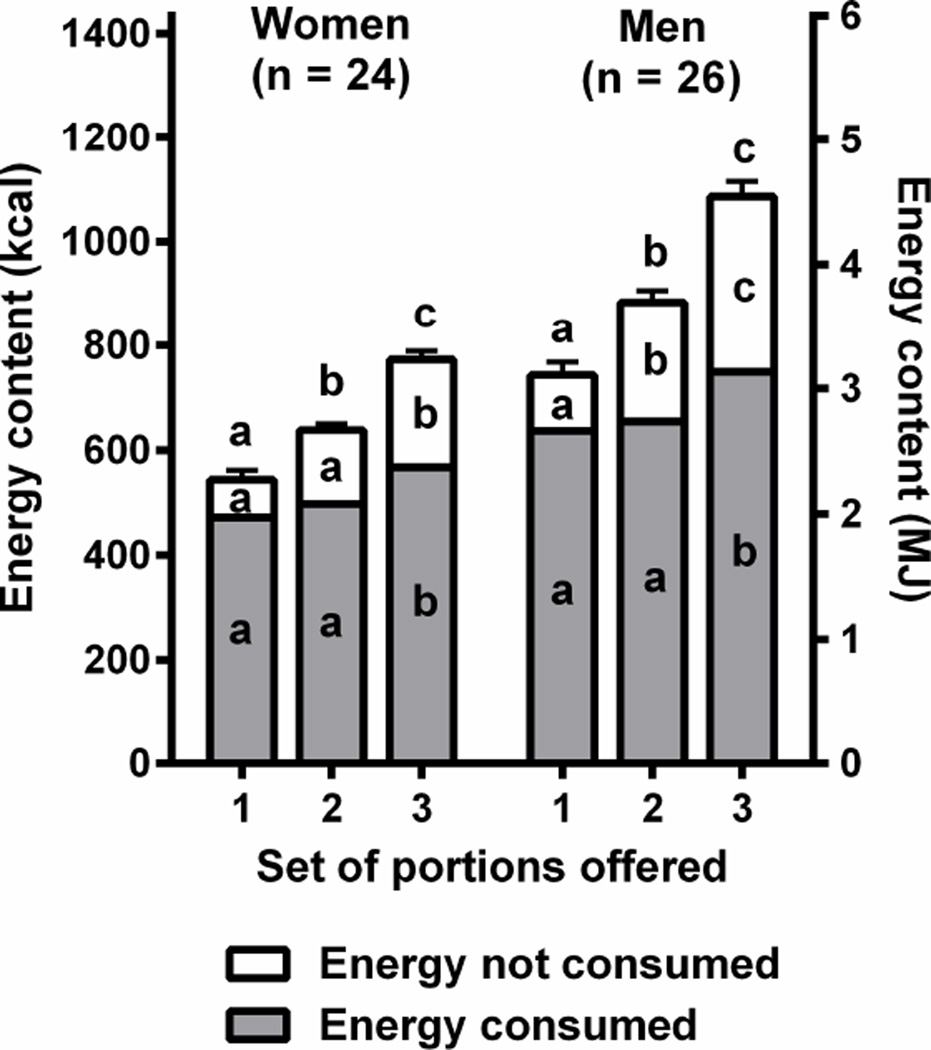

In contrast, increasing the size of the portions across the sets led to an increase in the mean weight of the selected portions (Fig. 1; P < 0.0001). Although there was one portion size that was offered in all three sets (450 g for women; 600 g for men), none of the subjects chose that portion in all three sets; thus, for all subjects, the portion they selected in Set 3 was larger than the portion they selected in Set 1.

Fig. 1.

Meal energy consumed, energy available but not consumed, and total energy available in the portion selected (mean and SEM) from each set of portions of macaroni and cheese offered. In a crossover design, subjects selected a portion from a set of three options, which were increased in size across the sets. For women the portions by weight (g) were: 300/375/450 (Set 1), 375/450/525 (Set 2), and 450/525/600 (Set 3); for men the portions were 400/500/600 (Set 1), 500/600/700 (Set 2), and 600/700/800 (Set 3). Within each sex, means with different letters are significantly different according to a mixed linear model with repeated measures (P < 0.03).

Intake from selected portions

Increasing the size of the set of portions offered to subjects had a significant effect on energy intake at the meal (Fig. 1; P < 0.0001). For both women and men, intake from the meal chosen from Set 3 was significantly greater than from the other two sets (P < 0.0001). Mean intake was 16% greater when the largest set was offered (2767 ± 140 kJ [661 ± 34 kcal]) than when the medium and smallest sets were offered (mean of both 2377 ± 77 kJ [568 ± 18 kcal]). The set of portions offered also had a significant influence on the proportion of the selected food that was consumed (P < 0.0001). Mean consumption of the portion selected was 85 ± 3% in Set 1, 76 ± 3% in Set 2, and 71 ± 3% in Set 3 for both women and men (all pairwise differences P < 0.03). Conversely, the amount of food left on the plate significantly increased with increasing set size (Fig. 1; P < 0.0001). For men, a significantly greater amount of food energy was left uneaten with each increasing set size, while women left similar amounts uneaten for Sets 1 and 2, but significantly more from the amount selected from Set 3.

Ratings of hunger, satiety, and food characteristics

Subject ratings of hunger, fullness, and prospective consumption (measured after selecting the portion but before consuming it) did not differ across the portion sets offered (P > 0.28). The relative size chosen within the set, however, did significantly affect before-meal ratings of prospective consumption (P = 0.025), but not hunger or fullness (P > 0.36). Across all meals, subjects who chose the largest portion in the set rated their prospective consumption higher than those who chose the smallest portion (66 ± 3 mm vs. 57 ± 2 mm; P < 0.05). After-meal ratings of hunger, satiety and prospective consumption did not differ according to either the set of portions offered or the relative size chosen. Thus, subjects did not rate their hunger or satiety differently, despite having consumed more energy from the meal in Set 3.

Subject ratings of food characteristics (assessed after selecting the portion from the set) indicated that they distinguished differences in the portion sizes that they selected from each set. In response to the question “How large is this portion of food?”, subjects rated the portion they selected from Set 3 as significantly larger (79 ± 2 mm; P < 0.0003) than those selected from Set 1 (67 ± 2 mm) and Set 2 (71 ± 2 mm). In response to the question “How does the size of this serving of food compare to your usual portion?”, subjects rated the portions they selected from Set 2 (72 ± 3 mm) and Set 3 (75 ± 2 mm) as significantly larger than that selected from Set 1 (66 ± 2 mm; P < 0.013). Thus, these ratings indicate that as all available portions became larger, subjects viewed their selected portion as both larger in general and larger than their usual portion. There were no significant differences in ratings of pleasantness of taste across the portion sets offered (overall mean 65 ± 2 mm; P = 0.76).

Influence of subject characteristics

For the outcome of portion selection, none of the measured subject characteristics affected the relationship between the portion set offered and the distribution of portions that were selected. For the outcome of meal energy intake, the relationship between portion set and energy intake was not influenced by subject height, weight, body mass index, age, or scores on the Eating Inventory. The scores on the Eating Attitudes Test (a measure of disordered attitudes towards eating and food), however, were found to significantly affect the relationship between portion set and energy intake (P < 0.0001). Subjects with higher scores on the Eating Attitudes Test consumed significantly less energy from Set 3 than from Set 1, in contrast to subjects with lower scores, who consumed more energy from Set 3 than from Set 1.

Discharge questionnaire

At discharge, 15 (30%) of the subjects reported noticing differences in the portion sizes of food presented at different test meals. Only 7 subjects (14%) guessed that the purpose of the study related to the effects of portion size or portion selection on food intake or appetite. Excluding these subjects from the analysis did not affect the significance of the main outcome. The majority of subjects (68%) indicated one of the following reasons for selecting their plate of food each week: 38% responded “I chose the one that was a certain size (small, medium, or large)” and 30% responded “I chose the one that matched my appetite that day”.

Discussion

In this study, we found that systematically increasing the size of three portion options at a meal had no significant influence on the relative portion size selected. Participants often selected the same relative size across all sets of portions, even when they had the opportunity to select smaller options. As a consequence, both the weight of the selected portion and energy intake from that portion increased significantly as all the portion options increased in size. Although subjects were offered a choice of portion sizes for their lunch, when all of the available options were large, they ate more than when the choices were smaller. These results further demonstrate the robust nature of the portion size effect. Although offering options allows consumers to compare portion sizes in making a choice, the absolute size of the available portions is a critical determinant of energy intake. Thus, in an eating environment where all portion options are large, individuals are likely to overconsume.

Several outcomes from the current study indicated that participants were aware of differences in portion size within the set, and that they used this information in selecting their portion at a given meal. Subject ratings of portion size differed across portion sets, showing awareness of differences in the portions selected. A large proportion of subjects (42%) chose the same relative portion size at all meals, much greater than that expected by chance (11%). Together, these findings imply that subjects chose their portion in relation to the other available sizes at a meal, a conclusion supported by responses on the discharge questionnaire. The consistency of portion selection demonstrated by many subjects implies the use of an anchoring and adjustment heuristic to determine meal choice (Marchiori, Papies & Klein, 2014; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). Despite the ability to distinguish the portion sizes offered, however, subjects did not adjust the relative portion size that they selected as all portions increased in size. Although the smallest available portion was selected at a majority of the meals, increases in all portions did not lead even more subjects to choose smaller relative portions; in particular the proportion of subjects who chose the medium or largest available portion did not decrease as all portions got larger. The failure to adjust selection of meal size in an environment of large portions might be due to habit, convenience (use of heuristics), value (more food for no additional cost), pre-meal decisions (Brunstrom, 2014; Robinson, te Raa & Hardman, 2015), or a lack of concern for the consequences at a single meal; this lack of adjustment could put individuals at risk for overconsumption.

Providing the opportunity to select portions from multiple options did not eliminate the effect of portion size on intake. There was no significant difference in intake between the meals selected from the two smaller sets, but when subjects were offered the largest set of portion sizes, energy intake at the meal increased by 16%. Notably, this effect was observed despite subjects leaving greater plate waste as all portions were increased, which may have been evidence of an attempt to moderate intake through use of visual cues (Burger, Fisher & Johnson, 2011; Fisher, Rolls, & Birch, 2003). The current study provides further evidence that the amount of food offered has a robust effect on intake (Rolls, 2014) and indicates that in the context of large portion sizes, offering a choice of portions may not mitigate intake. If all the portion options fall outside an appropriate range of energy, then individuals will be susceptible to overconsumption regardless of being offered a choice. This is especially important given the high energy content of many commercially available foods as well as many restaurant main dishes (Wu & Sturm, 2012).

The findings of this study provide little evidence that individual characteristics systematically influence the effect of portion size on intake. In a previous study it had been hypothesized that the portion size effect would be less pronounced in restrained eaters and more pronounced in disinhibited eaters (Rolls et al., 2002). In that study, as well as many of the subsequent portion size studies, neither dietary restraint, disinhibition, nor other measured subject characteristics (i.e. sex, age, or body mass index) were shown to influence the effect of increasing portion size on intake (i.e. Rolls, Roe, Kral, Meengs & Wall, 2004; Rolls, Roe, Meengs & Wall, 2004; Flood, Roe & Rolls, 2006; Rolls, Roe & Meengs, 2006). Likewise, in the present study, the portion size effect was not influenced by subject characteristics, with one exception. Scores on the Eating Attitudes Test did affect the relationship between the size of the set of portions and energy intake. Unlike most of the subjects, individuals scoring higher on this test (although still within the normal range) did not have greater energy intake as all the available portions got larger. This implies that individuals who are more preoccupied with food and eating behavior may be more conscious of changes in the amount of available food and adjust their intake in response.

This study used a novel design that allowed for the evaluation of selection and intake from among portion options of increasing size, but it is important to interpret the results in context. The portions offered were based on the average intake observed in similar studies offering macaroni and cheese as the only test food. Although we offered large amounts of food, sufficient to ensure most subjects would not consume the entire portion, the range of energy served was consistent with that of similar dishes at a number of popular restaurants. While our findings again demonstrate the robust nature of the portion size effect (albeit in a novel paradigm), offering portion sizes different from the ones in this study may yield different results both in terms of selection and intake. Future research could examine how the response to portion options might be influenced by personal and social norms (Lewis et al., 2015a) or by offering a broader range of portion sizes that are both larger and smaller than typically served (Lewis, Ahern, Solis-Trapala, Walker, Reimann, Gribble & Jebb, 2015b). Moreover, the laboratory setting of the study may have influenced the results, although it was controlled across experimental conditions. Future studies should determine whether the findings reported here apply in more naturalistic settings that include influences other than the portion manipulation (such as social influence, cost, and competing foods) in order to extend the ecological validity of these findings.

That portion size affected intake despite many participants’ choice of the smallest portion among the options has important implications given the current eating environment. Large portions are very prevalent; meals from nearly half of the top 400 restaurant chains nationwide offer more energy than is recommended by public health agencies for a single meal (Wu & Sturm, 2012). Given that large portions of food often provide an excess of energy, it is important to moderate the energy content of the portion options in the eating environment and to determine strategies to promote choices that fall within an appropriate range for energy needs. Such strategies could be implemented at the level of the food provider, and include incentivizing the selection of portion choices that offer a more appropriate amount of energy (e.g. through pricing) or reducing the energy density of the available portions so that larger portions do not necessarily result in overconsumption of energy. As shown in the present study, even when consumers are given the opportunity to select a portion from a range of sizes, when the portion options are large, individuals are still likely to overconsume.

Research Highlights.

Subjects chose and ate a portion of pasta from 3 sets, each with 3 portion options

Offering larger portions in the set did not affect the relative size selected

Despite the options, intake was 16% higher from the set with the largest portions

The sizes of the portions offered are a critical determinant of energy intake

Acknowledgments

Funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK059853)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Benton D. Portion size: what we know and what we need to know? Critical reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2014;55(7):988–1004. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.679980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunstrom JM. Mind over platter: pre-meal planning and the control of meal size in humans. International Journal of Obesity. 2014;38:S9–S12. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger KS, Fisher JO, Johnson SL. Mechanisms behind the portion size effect: visibility and bite size. Obesity. 2011;19(3):546–551. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English L, Lasschuijt M, Keller KL. Mechanisms of the portion size effect. What is known and where do we go from here? Appetite. 2015;88:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Rolls BJ, Birch LL. Children’s bite size and intake of an entrée are greater with large portions than with age-appropriate or self-selected portions. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;77:1164–1170. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2000;24(1):38–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood JE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. The effect of increased beverage portion size on energy intake at a meal. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine. 1982;12:871–878. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier AB, Rozin P, Doros G. Unit bias: a new heuristic that helps explain the effect of portion size on food intake. Psychological Science. 2006;17(6):521–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CP, Polivy J, Pliner P, Vartanian LR. Mechanisms underlying the portion-size effect. Physiology & Behavior. 2015;144:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrates, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB, Ahern AL, Solis-Trapala I, Walker CG, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Jebb SA. Effect of reducing portion size at a compulsory meal on later energy intake, gut hormones, and appetite in overweight adults. Obesity. 2015b;23(7):1362–1370. doi: 10.1002/oby.21105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB, Forwood SE, Ahern AL, Verlaers K, Robinson E, Higgs S, Jebb SA. Personal and social norms for food portion sizes in lean and obese adults. International Journal of Obesity. 2015a;39:1319–1324. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchiori D, Papies EK, Klein O. The portion size effect on food intake. An anchoring and adjustment process? Appetite. 2014;81:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation’s Restaurant News. [Retrieved 28 September 2015];Top 100 chains: U.S. Sales. 2012 from http://nrn.com/us-top-100/top-100-chains-us-sales. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E, te Raa W, Hardman CA. Portion size and intended consumption. Evidence for a pre-consumption portion size effect in males? Appetite. 2015;91:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ. What is the role of portion control in weight management? International Journal of Obesity. 2014;38:S1–S8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Morris EL, Roe LS. Portion size of food affects energy intake in normal-weight and overweight men and women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76:1207–1213. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Halverson KH, Meengs JS. Using a smaller plate did not reduce energy intake at meals. Appetite. 2007;49(3):652–660. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Kral TVE, Meengs JS, Wall DE. Increasing the portion size of a packaged snack increases energy intake in men and women. Appetite. 2004;42:63–69. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00117-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Larger portion sizes lead to a sustained increase in energy intake over 2 days. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS, Wall DE. Increasing the portion size of a sandwich increases energy intake. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1985;29(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer WM, Alting E, Steenhuis IHM, Seidell JC. Value for money or making the healthy choice: the impact of proportional pricing on consumers’ portion size choices. European Journal of Public Health. 2010;20(1):65–69. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp092. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer WM, Steenhuis IHM, Leeuwis FH, Bos AER, de Boer M, Seidell JC. Portion size labeling and intended soft-drink consumption: the impact of labeling format and size portfolio. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior. 2010;42(6):422–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer WM, Steenhuis IHM, Leeuwis FH, Heymans MW, Seidell JC. Small portion sizes in worksite cafeterias: do they help consumers to reduce their food intake? International Journal of Obesity. 2011;35:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer WM, Steenhuis IHM, Seidell JC. From the point-of-purchase perspective: A qualitative study of the feasibility of interventions aimed at portion-size. Health Policy. 2009;90:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer WM, Steenhuis IHM, Seidell JC. Portion size: a qualitative study of consumer’s attitudes toward point-of-purchase interventions aimed at portion size. Health Education Research. 2010;25(1):109–120. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HW, Sturm R. What’s on the menu? A review of the energy and nutritional content of US chain restaurant menus. Public Health Nutrition. 2012;16(1):87–96. doi: 10.1017/S136898001200122X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LR, Nestle M. Reducing portion sizes to prevent obesity: A call to action. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43(5):565–568. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WK. Zung self-rating depression scale and depression status inventory. In: Sartorius N, Ban TA, editors. Assessment of Depression. Berlin, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1986. pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]