Abstract

Purpose

Family meetings can be challenging, requiring a range of skills and participation. We sought to identify tools available to aid the conduct of family meetings in palliative, hospice, and intensive care unit settings.

Methods

We systematically reviewed PubMed for articles describing family meeting tools and abstracted information on tool type, usage, and content.

Results

We identified 16 articles containing 23 tools in 7 categories: meeting guide (n = 8), meeting planner (n = 5), documentation template (n = 4), meeting strategies (n = 2), decision aid/screener (n = 2), family checklist (n = 1), and training module (n = 1). We found considerable variation across tools in usage and content and a lack of tools supporting family engagement.

Conclusion

There is need to standardize family meeting tools and develop tools to help family members effectively engage in the process.

Keywords: communication, professional–family relations, interdisciplinary communication, palliative care/psychology, caregivers, review

Introduction

Consistent communication among patients, families, and care providers is a vital aspect of high-quality end-of-life (EOL) care.1 Family meetings are recognized as an effective method for facilitating such communication, and several EOL practice guidelines routinely highlight their importance.2–6 Family meetings offer a venue for patients, family members, and providers to discuss the patient’s condition and prognosis, share information regarding the patient’s preferences, and align goals of care. Family meetings have been shown to improve concordance of care with expressed wishes7–9 and reduce posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression among bereaved family members. They are also associated with reduced length of inpatient stay and higher ratings of the quality of the dying experience.7,9–11

Effective conduct of family meetings is a nontrivial task. It requires a wide range of skills, particularly in empathic communication that provides support, minimizes stress among family members, and meets basic standards for informed decision making.12 Most providers do not receive formal training in conducting family meetings and do not feel adequately prepared to participate in them, which can exacerbate the challenges of conducting them effectively.13–15

The use of health care tools to aid the conduct of family meetings has potential to facilitate translation of research into clinical practice and increase the routine conduct and effectiveness of these meetings. Health care tools such as decision support aids,16 clinical templates,17 and safety checklists18 have been shown to successfully support a range of routine clinical processes including screening/assessment,19 documentation,20,21 communication,22 and health information exchange.23 Health care tools are particularly useful for clinical processes that share common features across cases with potential for standardization. While each family meeting is unique in its content and conduct, prior work has suggested that family meetings as a whole share common elements that can be explicitly defined and structured.24–26 The purpose of this systematic review was to identify and describe existing tools available to aid the conduct of family meetings in palliative, hospice, and intensive care unit (ICU) care settings for use in quality improvement activities. We focused on decision aids, documentation tools, or other resources that could be incorporated into electronic health records.

Methods

Search Strategy

We systematically searched the PubMed electronic database for English-language articles published from inception through August 2013 describing work conducted in the United States, Canada, England, and Australia. Studies could be of any design. We used several combinations of Medical Subject Headings terms to identify the various ways family meetings are described in the literature and the range of EOL settings in which they occur (Appendix A). Given the multiple ways health care tools might be described in the literature, we did not include specific search terms to indicate “tool” but instead incorporated this into our inclusion criteria as described subsequently. To identify additional tools that may not have been captured by the search strategy or described in the published literature, we drew on members of the study team with expertise in family meetings and EOL care (KAL and SCA).

Article Selection

We included articles that described or tested tools that (1) supported the conduct of family meetings in palliative, hospice, or ICU settings; (2) were developed with the intent of being used in clinical environments; and (3) were described in enough detail that they could be reliably implemented and replicated in clinical practice. Tools did not have to be formally tested in these environments to be included in our review. Sources and tools identified through expert review were subject to the same inclusion criteria.

We excluded articles describing (1) communication tools not explicitly intended for use in family meetings; (2) models of communication that did not directly inform a tool as described earlier; and (3) family meeting tools for use in pediatric populations (age <18 years).

Two reviewers with expertise in systematic review methodology and health services research (AS and TA) conducted independent dual review of identified references first by title and abstract, then by full text. At each stage, disagreements about inclusion or exclusion were adjudicated by a third investigator (KAL or SCA).

Analysis

Articles included after full-text screening were divided and abstracted by study/source and tool into a data abstraction file. We categorized tools by the stage of the family meeting they were intended for premeeting, including preparation, planning, and scheduling; during the meeting, including structure, topics, and communication processes; and postmeeting, including documentation and follow-up. We also qualitatively abstracted detailed information about what the tools were composed of and how they were developed.

Results

Literature Search

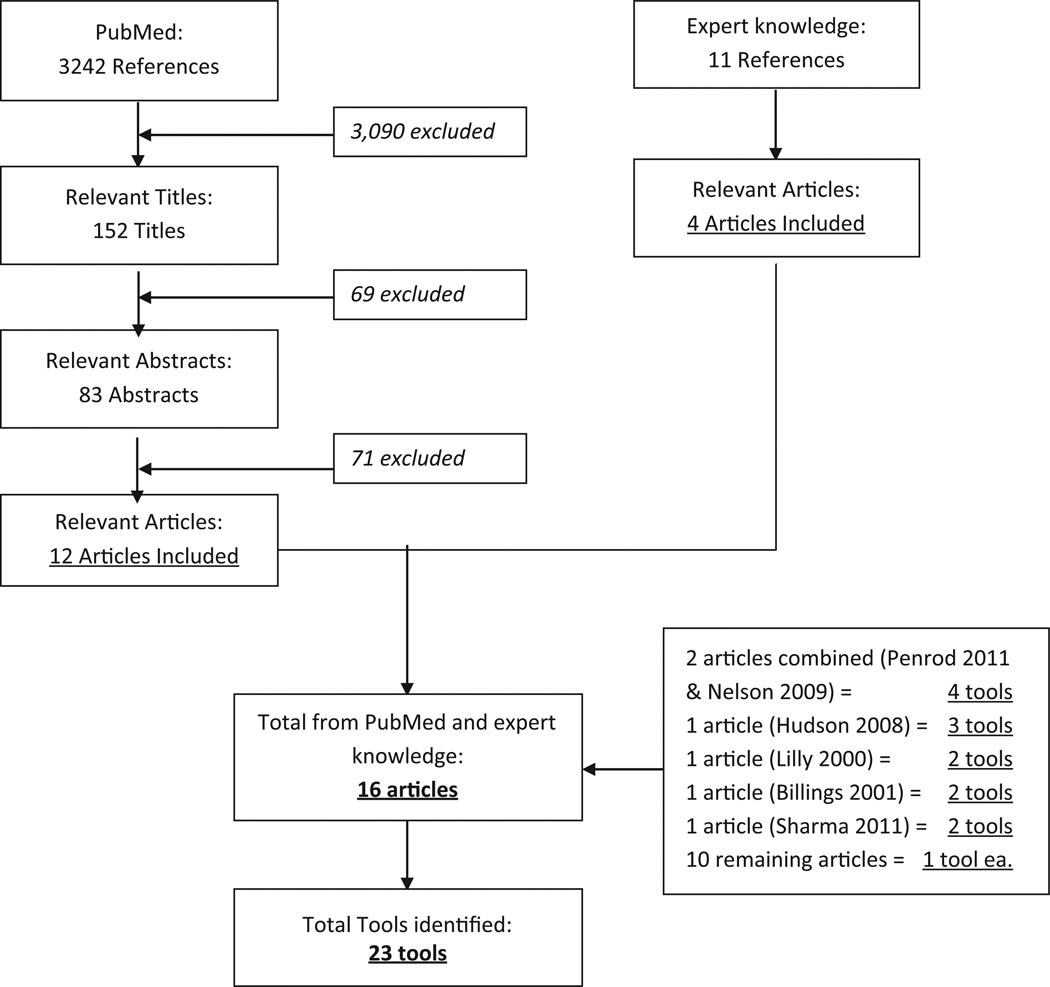

Our initial PubMed search identified 3242 references, which we narrowed down to 152 relevant articles after title screening, and 83 articles after abstract screening. Full review of these 83 articles identified 12 articles that met inclusion criteria. Expert review identified an additional 11 references of potential relevance, which were narrowed down to 4 articles that met inclusion criteria. Of the 16 included articles, 2 articles described the same set of 4 tools and thus were counted as 1 article with 4 tools,27,28 1 article described 3 separate tools,29 and 3 articles described 2 separate tools each.9,30,31 In total, we identified 23 family meeting tools (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature flow.

Types of Tools

We identified 7 types of tools described in the 16 included articles: meeting guide or agenda (n = 8), meeting planner (n = 5), documentation template (n = 4), meeting strategies (n = 1 communication strategy and n = 1 conflict management strategy), decision aid/screener (n = 2), family checklist (n = 1), and training module (n = 1; Table 1). Subsequently, we describe key features of the identified tools by type and stage of meeting. For the 2 articles describing the same set of 4 tools,27,28 we hereafter only reference Nelson et al27 as the source and developer of the tools. Table 2 lists each tool by the stage of the family meeting it was intended to address: premeeting, during meeting, and postmeeting.

Table 1.

Description of Studies.

| No. | First author/year | Type of tool | Tool evaluated in patients/families or providers; study design |

Description | Development process/source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified through pubmed search | 1 | Whitmer M (2005) | Documentation template |

No | ICU family meeting progress note that included free-text space to document family concerns expressed during the meeting |

Based on process improvement research on interdisciplinary communication |

| 2 | Hudson P (2008) | Meeting guide/ agenda |

No | Outlines key agenda topics, including introductions, determining understanding of the purpose of the meeting, asking patients about questions/concerns, determining what the patient and family already know, addressing predetermined objectives, and providing resources and information |

Literature review, expert panel, and focus groups with physicians |

|

| Meeting planner | No | Eight steps to prepare for a family meeting, including introducing and offering the family meeting on admission of the patient, identifying family member participants, identifying a meeting leader from the clinical team and other providers, and confirming meeting time and location |

||||

| Documentation template |

No | Recommendations for what to document, including attendees, decisions made, and follow-up plan |

||||

| 3 | Gueguen JA (2009) | Training module | Providers; pre–post | A palliative care family meeting communication skills training module for health care professionals that was composed of 6 key categories of skills particularly relevant to family meetings to be taught during the training: (1) establishing the consultation framework; (2) information organization; (3) checking; (4) questioning; (5) empathic communication; and (6) shared decision making |

Based on the Comskil conceptual model of communication skills training evaluated the module using participant satisfaction and rating of self-efficacy in conducting family meetings |

|

| 4 | Machare Delgado E (2009) | Documentation template |

Patients/families; pre–post | A multidisciplinary team and family meeting form that includes a problem list, goals of care, symptom assessments, and meeting attendees |

Based on palliative care literature on communication during family meetings |

|

| 5 | Ambuel B (2009) | Meeting guide/ agenda |

No | “Fast Facts and Concepts” guide outlining process steps for a family conference |

Evidence-based summaries on select topics in end-of-life care |

|

| 6 | Weissman DE (2009) | Meeting planner | No | “Fast Facts and Concepts” guide outlining steps to prepare for a family meeting, including reviewing medical data, synthesizing information, and identifying meeting leaders and setting |

||

| 7 | Weismann DE (2009) | Meeting guide/ agenda |

No | “Fast Facts and Concepts” guide for conducting the early stages of a family meeting that includes introductions, determining what the family knows, and opening lines |

||

| 8 | Weismann DE (2010) | Communication strategy |

No | “Fast Facts and Concepts” guide for acknowledging and responding to emotions that arise during family meetings |

||

| 9 | Weissman DE (2010) | Conflict management strategy |

No | “Fast Facts and Concepts” guide for developing a strategy to address and manage conflict during family meetings by addressing underlying causes |

||

| 10 | Fineberg IC (2011) | Meeting guide/ agenda |

No | Meeting guide for structuring family meetings that include introductions, agenda setting, review of patient history, diagnosis, prognosis, care plan and discharge plan, and follow-up |

Analysis of videotaped and audiotaped family meetings |

|

| 11 | Billings JA (2011) | Meeting planner | No | Steps for preparing for family meetings, including setting up an agenda and agreeing on goals, identifying family invitees and determining staff participation, and holding a premeeting staff conference to reach agreement on how to conduct the family meeting |

Literature review of ICU family meetings | |

| Meeting guide/ agenda |

No | Guide for conducting ICU family meetings in situations in which the patient cannot participate, including introducing participants, assessing family understanding of the patient’s condition, eliciting preferences for information and decision-making, discussing what it is like for the patient now, and exploring family beliefs about what the patient would want |

||||

| 12 | Sharma RK (2011) | Meeting planner | No | Steps for preparing for family meetings with consideration of cross-cultural issues, including arranging for a professional medical interpreter and meeting with interpreter before the family meeting to review the purpose of the meeting and relevant cultural information |

Narrative review | |

| Meeting guide/agenda | No | Guide for conducting palliative care family meetings with consideration of cross-cultural issues, including involving an interpreter, asking the interpreter to state when he or she is providing strict interpretation versus interjecting his or her own comments, and regularly checking in with family to evaluate understanding |

||||

| Identified via expert review | 1 | Lilly CM (2000) | Meeting guide/agenda |

Patients/families; pre–post | Agenda specifying 4 objectives: review medical facts, discuss patient perspectives on EOL care, agree on care plan, and agree on criteria for judging success or failure of care plan |

Not provided |

| Decision aid/ screener |

Patients/families; pre–post | List of clinical variables to determine the need for a family meeting, including predicted length of stay, predicted mortality, and change in functional status |

||||

| 2 and 3 |

Nelson JE (2009) and Penrod JD (2011) |

Meeting planner | Patients/families (Penrod only); pre–post |

Template outlining steps necessary to prepare for a day 5 family meeting in the ICU, including identifying a surrogate, establishing team consensus on meeting goals, and preparing an agenda |

Literature review, expert consensus, survey data |

|

| Decision aid/ screener |

Patients/families (Penrod only); pre–post |

A screening tool that uses clinical variables to determine the likelihood of a ≥5 days stay in the ICU, including S/P cardiac arrest, advanced malignancy, or multisystem organ failure |

||||

| Family checklist | Patients/families (Penrod only); pre–post |

Checklist to help prepare families to participate in family meetings |

||||

| Documentation template |

Patients/families (Penrod only); pre–post |

Template specifying key elements of family meetings to be documented, including attendees, patient participation, and topics of discussion |

||||

| 4 | Daly BJ (2010) | Meeting guide/ agenda |

Patients/families; controlled clinical trial |

Agenda specifying required family meeting content, including a medical update, patient values and preferences, goals of care, treatment plan, and milestones for determining success or failure of the treatment plan |

Not provided |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; EOL, end-of-life care.

Table 2.

Tools Organized by Stage of Family Meeting (Premeeting, During Meeting, and Postmeeting).

| Stage of meeting |

Type of tool | First author/year |

|---|---|---|

| Premeeting | Meeting planner |

Hudson P (2008) Weissman DE (2009) Billings JA (2011) Sharma RK (2011) Nelson JE (2009)/Penrod JD (2011) |

| Decision aid/screener |

Lilly CM (2000) Nelson JE (2009)/Penrod JD (2011) |

|

| Family checklist | Nelson JE (2009)/Penrod JD (2011) | |

| Training module | Gueguen JA (2009) | |

| During meeting | Meeting guide/agenda |

Lilly CM (2000) Hudson P (2008) Ambuel B (2009) Weismann DE (2009) Daly BJ (2010) Fineberg IC (2011) Billings JA (2011) Sharma RK (2011) |

| Communication strategy | Weismann DE (2010) | |

| Conflict management strategy | Weissman DE (2010) | |

| Postmeeting | Documentation template |

Whitmer M (2005) Hudson P (2008) Machare Delgado E (2009) Nelson JE (2009)/Penrod JD (2011) |

Premeeting Tools

Meeting planner (n = 5)

We identified 5 family meeting planners that described steps to be taken in preparation for a family meeting.27,29–32 All 5 tools were developed using literature review and sometimes expert panel opinion. All meeting planners included logistical steps necessary for conducting a family meeting, such as identifying and inviting family members/surrogate decision makers to be present at the meeting, identifying care team members to participate and designating a meeting leader, and confirming the time and location of the family meeting. Three of the 5 planners also suggested a premeeting among the care team participants to establish consensus on the meeting goals and agenda and meeting leadership.27,31,32 One of the planners specified the need for a premeeting data review, to review the patient’s medical history, evaluate likely prognosis, elicit medical opinions of consultants, review advance directive information, and make determinations regarding potential care plans.32 Only 1 of the 5 meeting planners was time defined,27 in that it specified certain steps to be undertaken in the days preceding the family meeting (ie, identifying surrogate information on the day of ICU admission and scheduling the meeting within the first 72 hours). Another meeting planner highlighted specific considerations for family meetings in a cross-cultural context, including meeting with a professional medical interpreter to review the purpose of the family meeting and relevant cultural information.30

Decision aid/screener (n = 2)

We identified 2 decision aids or screeners that identify patients likely to need a family meeting on the basis of clinical factors.9,27 One of these tools was developed using literature review, expert consensus, and survey data27; the development of the other was not described.9 One listed variables to be identified by the attending physician which were likely to indicate the need for a family meeting in the ICU, such as predicted length of stay >5 days, predicted mortality >25% as estimated by the physician, or a potentially irreversible change in functional status sufficient to preclude return to home.9 The other focused specifically on clinical variables indicating the likelihood of a ≥5-day stay in the ICU, such as S/P cardiac arrest, advanced malignancy, multisystem organ failure, or age older than 80 years with comorbidity.27

Family checklist (n = 1)

We identified a single family checklist aimed at helping families organize their thoughts, prepare questions, and maximize their time in the family meeting.27 This tool was developed using literature review, expert consensus, and survey data. It included suggestions such as reviewing what the family knows about the patient’s illness and treatment, identifying topics for clarification with the care team, writing down concerns or fears to be shared, and identifying goals for the family meeting.

Training module (n = 1)

We identified 1 communication skills training module for health care providers that addressed how to conduct a family meeting in palliative care.33This tool was developed using the Comskil conceptual model of communication skills training. The module was composed of 6 key categories of skills particularly relevant to family meetings to be taught during the training: (1) establishing the consultation framework, (2) information organization, (3) checking, (4) questioning, (5) empathic communication, and (6) shared decision making.

During Meeting Tools

Meeting guide/agenda (n = 8)

We identified 8 meeting guides/agendas, each specifying different levels of guidance regarding content and process of family meetings.9,29–31,34–37 These were developed using various methods, including literature review,29,30,38 existing conceptual frameworks and expert panel guidance,29 and analysis of videotaped and audiotaped family meetings.39 Two articles, each testing the impact of a multifaceted family meeting intervention on patient37 and family9 outcomes, specified objectives for the meeting, including the review of medical facts, the identification of patient preferences for care, the development of an agreement on a care plan, and the determination of clinical milestones to judge the success or failure of the care plan. Several other articles29,34–36 added to this by describing specific processes to help satisfy the meeting objectives, such as determining what the family wants to know and eliciting family understanding, summarizing disagreements and consensus, providing information and resources, and responding to family concerns and questions. Two meeting guides were designed with specific considerations for conducting family meetings in situations in which the patient could not participate31 or in which cross-cultural issues were present.30

Meeting strategies (n = 2)

We identified 2 articles that described strategies to help clinicians address and manage difficult situations that might arise during family meetings. Both were developed using literature review. One details discrete steps for responding to strong emotional reactions,40 including acknowledging, legitimizing, and empathizing with the emotion and exploring reasons and feelings underlying the emotion. The other included strategy describes steps for evaluating the causes of conflict during family meetings,41 including identifying complex emotions that might hinder acceptance of the situation and gaps in information that the family might have, such as inaccurate understanding of the patient’s condition or confusion about treatment goals.

Postmeeting Tools

Documentation template/progress note (n = 4)

We identified 4 documentation templates, each specifying key content and outcomes of the family meeting to be documented in the patient’s medical record.27,29,42,43 All 4 templates were developed using literature review and expert panel opinion. They all included space to record meeting attendance, and some included the extent of patient participation in the meeting (eg, cognitive capacity),27 free-text space to document the topics of discussion during the meeting, and a place to record advance directive information and code status. Templates varied in all other elements of documentation. For example, one included space to record the patient’s problem list and symptom assessment information,42 and others included free-text space to document family understanding of the family meeting content and the patient’s clinical situation.27 Only 1 template included free-text space to document family concerns expressed during the meeting,43 and another template included space to record decisions made and a follow-up plan.29

Tool Efficacy

Of the 16 included articles, only 4 formally tested their tools in clinical environments with patient and family populations. Three used pre–post designs,9,28,42 and 1 was a controlled clinical trial.37 Two of the 4 described multiple tools that were tested together as part of comprehensive family meeting interventions.9,28 Three of the 4 showed significant impacts on process and outcome measures: life support withdrawal,42 reduced ICU length of stay,9 and a variety of ICU quality measures, including identification of medical decision maker and offer of social work support.28 However, family meeting tools were only one of many components of the latter’s intervention. The fourth was unable to show significant changes in ICU length of stay, aggressiveness of care, or treatment limitation decisions.37

One study evaluated the effect of its tool in a population of providers who conduct family meetings and found that providers were satisfied with the tool and reported significantly improved self-efficacy in conducting family meetings.33 It used a pre–post design. There was no association between type of tool and efficacy in improving patient/family or provider outcomes.

Discussion

Our systematic review identified 23 tools used to aid the conduct of family meetings in palliative, hospice, and ICU settings pre-, during, and postmeeting. The most common tools identified were meeting guides/agendas and documentation templates. Only 1 identified tool was aimed at family participants, and the majority were designed to support provider practice. There is a large research base that addresses many different aspects of family meetings (eg, studies that classify provider communication patterns observed during family meetings),24–26 and EOL care guidelines argue that family meetings should be a routine part of care for patients with advanced illness.4,6 In spite of this, our review found that there is little standardized guidance available for structuring these meetings in practice.

Meeting guides/agendas were the most common type of tool identified, and the majority shared core elements recommended in prior work.24,26,44 These elements included introducing participants, reviewing medical history, evaluating patient and family understanding of the clinical situation, discussing the patient’s values and preferences, and making decisions if appropriate. The availability of existing meeting guides/agendas that share common elements can help to structure the emotionally complex task of communicating about EOL care, reduce process variability, and support quality improvement in family meeting conduct across settings and health care systems. Future work might focus on strengthening the linkage between the family meeting agenda and documentation for follow-up from the meeting.

Our search identified several documentation templates, many of which included space for patient and family information, content and topics of discussion, and any decisions made. Among these templates, we found little focus on key elements of follow-up, such as documentation of clinical milestones or date of the next family meeting. We also found little focus on documenting family questions and concerns, which is critical to family-centered care, to improving communication between care team providers and family members following the family meeting, and to sharing consistent information within the care team and assuring timely follow-up and accountability. There is some concern that overly standardizing family meeting documentation templates may lead to the mechanization of interpersonal communication; however, our findings suggest there is still room to identify core elements for documentation across family meetings, particularly those elements that support follow-up and consistent communication.

We identified 2 decision aids/screeners that proactively identify patients likely to need a family meeting, both for use in the ICU. Both screeners employed clinical variables such as predicted mortality or conditions likely to result in a longer length of stay. This approach has also been successfully employed in triggering palliative care consultations.11,45 Although useful, such screeners overlook the importance of family members’ communication and information needs as the motivation for family meetings. Family meetings may be relevant in cases in which multiple family members are involved or disagreement regarding the patient’s preferences arises, regardless of clinical status. Future work may need to focus on developing additional screening criteria to ensure more appropriate and timely access to family meetings.

Our search identified only 1 tool that helps families prepare to participate in the family meeting. Informed family participation in family meetings at the EOL is critical to helping family members comprehend the clinical situation, provide substituted judgment, and effectively serve as surrogate decision makers. Moreover, there is consensus that while physicians are obligated to provide information about a patient’s condition and prognosis to the family, family members can be a critical source of information regarding the patient’s values and preferences.12 Various professional societies have highlighted the importance of supporting and involving the family at the EOL.46–48 There may need to be greater attention placed on tools that are designed to help families effectively engage with clinicians and participate in decision making during family meetings.

Only one-quarter of the included articles formally tested their tools in clinical environments with patient and family populations and evaluated their impact on clinical process and outcome measures, and one other article evaluated its tool in a provider population. These articles suggest that family meeting tools can be effective in promoting provider self-efficacy and addressing a range of patient and family quality and utilization outcomes, especially when employed as part of comprehensive patient- and family-focused interventions. However, more and higher quality evidence is needed to refine our understanding of the impact of these tools: Most studies did not evaluate their tools at all, and the ones that did employed mostly low-quality study designs.

Our review has some limitations. Although we used a large database of indexed references on biomedical topics and supplemented our search with expert review, as with any systematic literature review, our search strategy may have missed some relevant articles. For the sake of feasibility, we limited the geographic scope of our search and may have overlooked relevant tools described in other countries. The heterogeneity and limited information found on each tool precluded a meta-analysis. Finally, we limited our search to family meetings in palliative, hospice, and ICU care because they are primarily conducted in these settings. It is possible that our review excluded family meeting tools designed for other domains; however, given that most research on family meetings is performed in the context of EOL care, this is unlikely to be a major concern.

In summary, we identified a number of tools that aid the conduct of family meetings and can provide structure and support for a critical and complex communication task. There is potential for further standardizing such tools and developing new tools to help family participants effectively engage in the process. There is also a need for further research in leveraging electronic resources to facilitate family meetings. All family meeting tools should be evaluated at high levels of evidence in order to assess their efficacy and promote their uptake.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the VA palliative care Quality Improvement Resource Center in order to identify family meeting tools for use in quality improvement.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Singer received support from grant T32 GM008042 as a member of the Medical Scientist Training Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Ahluwalia was supported by a career development award from the National Palliative Care Research Center and a VA/NIMH Implementation Research Fellowship (R25 MH080916-01A2).

Footnotes

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

References

- 1.von Gunten CF, Ferris FD, Emanuel LL. The patient-physician relationship. Ensuring competency in end-of-life care: communication and relational skills. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3051–3057. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: a consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11 suppl):S404–S411. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Operational features for hospital palliative care programs: consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(9):1189–1194. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Third Edition. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109(6):469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glavan BJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, Curtis JR. Using the medical record to evaluate the quality of end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1138–1146. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123(1):266–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134(4):835–843. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler DJ, Holloway RL, Gottlieb M. Predicting resident confidence to lead family meetings. Fam Med. 1998;30(5):356–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jubelirer SJ, Welch C, Babar Z, Emmett M. Competencies and concerns in end-of-life care for medical students and residents. W V Med J. 2001;97(2):118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld LA, et al. End-of-life care for the critically ill: A national intensive care unit survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(10):2547–2553. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryan C, Boren SA. The use and effectiveness of electronic clinical decision support tools in the ambulatory/primary care setting: a systematic review of the literature. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16(2):79–91. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i2.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry SB, Morris JA, Holzemer WL. Using structured text and templates to capture health status outcomes in the electronic health record. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1997;23(12):667–677. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hales BM, Pronovost PJ. The checklist–a tool for error management and performance improvement. J Crit Care. 2006;21(3):231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, Rosenbloom ST, Aronsky D. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(3):311–320. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartz T, Verst H, Ueckert F. KernPaeP - a web-based pediatric palliative documentation system for home care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;150:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindner SA, Davoren JB, Vollmer A, Williams B, Landefeld CS. An electronic medical record intervention increased nursing home advance directive orders and documentation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):1001–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russ S, Rout S, Sevdalis N, Moorthy K, Darzi A, Vincent C. Do safety checklists improve teamwork and communication in the operating room? A systematic review. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):856–871. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Studying communication about end-of-life care during the ICU family conference: development of a framework. J Crit Care. 2002;17(3):147–160. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2002.35929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White DB, Braddock CH, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson JE, Walker AS, Luhrs CA, Cortez TB, Pronovost PJ. Family meetings made simpler: a toolkit for the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):626. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.02.007. e627-e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penrod JD, Luhrs CA, Livote EE, Cortez TB, Kwak J. Implementation and evaluation of a network-based pilot program to improve palliative care in the intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(5):668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudson P, Quinn K, O’Hanlon B, Aranda S. Family meetings in palliative care: Multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines. BMC Palliat Care. 2008;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma RK, Dy SM. Cross-cultural communication and use of the family meeting in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(6):437–444. doi: 10.1177/1049909110394158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Billings JA, Block SD. The end-of-life family meeting in intensive care part III: A guide for structured discussions. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(9):1058–1064. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0038-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM. Preparing for the family meeting #222. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(2):203–204. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gueguen JA, Bylund CL, Brown RF, Levin TT, Kissane DW. Conducting family meetings in palliative care: themes, techniques, and preliminary evaluation of a communication skills module. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(2):171–179. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fineberg IC, Kawashima M, Asch SM. Communication with families facing life-threatening illness: a research-based model for family conferences. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):421–427. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM. The family meeting: starting the conversation #223. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(2):204–205. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ambuel B, Weissman DE. Moderating an end-of-life family conference, 2nd edition. [Accessed May 2, 2014];Fast Facts and Concepts. 2005 Web site. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_016.htm. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daly BJ, Douglas SL, O’Toole E, et al. Effectiveness trial of an intensive communication structure for families of long-stay ICU patients. Chest. 2010;138(6):1340–1348. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Billings JA, Block SD. The end-of-life family meeting in intensive care part III: A guide for structured discussions. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(9):1058–1064. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0038-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fineberg IC, Kawashima M, Asch SM. Communication with families facing life-threatening illness: a research-based model for family conferences. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):421–427. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM. Responding to emotion in family meetings #224. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(3):327–328. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissman DE, Quill TE, Arnold RM. The family meeting: causes of conflict #225. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(3):328–329. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Machare Delgado E, Callahan A, Paganelli G, Reville B, Parks SM, Marik PE. Multidisciplinary family meetings in the ICU facilitate end-of-life decision making. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(4):295–302. doi: 10.1177/1049909109333934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitmer M, Hughes B, Hurst SM, Young TB. Innovative solutions: family conference progress note. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2005;24(2):83–88. doi: 10.1097/00003465-200503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Rubenfeld GD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(8):844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, Temkin-Greener H, Buckley MJ, Quill TE. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(8):912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]