Abstract

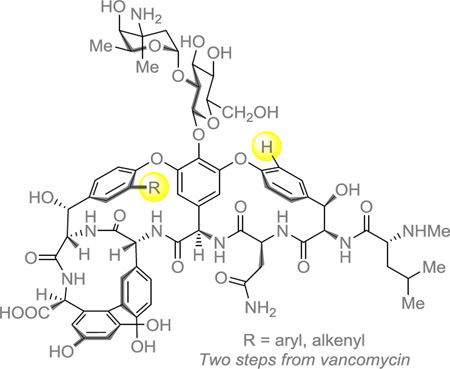

In an effort to rapidly access vancomycin analogues bearing diverse functionality at the 6c-Cl (the “in-chloride”) position, a two-step dechlorination/cross-coupling protocol was developed. Conditions for efficient cross-coupling of the relatively unreactive 6c-Cl group were found that ensure high conversion with minimal product decomposition. A set of 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin derivatives was prepared, and antibiotic activities of the compounds were evaluated against a panel of vancomycin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible strains. Results from biological testing further underscore the steric sensitivity of vancomycin’s binding pocket.

Keywords: Vancomycin, Vancomycin analogues, Cross-coupling

Graphical abstract

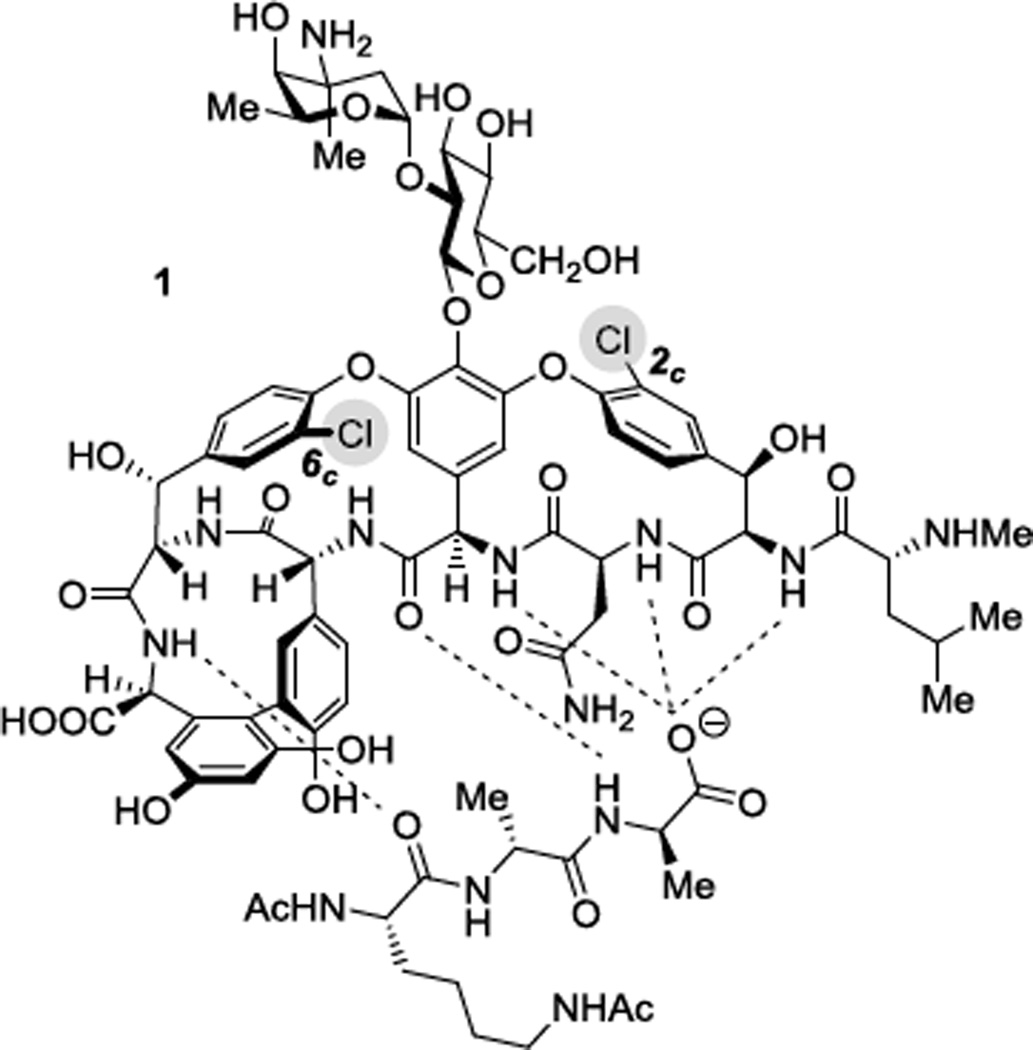

Glycopeptide natural product antibiotics, vancomycin (1) in particular, have seen widespread use and extensive study over the past half century.1,2 The glycopeptide antibiotics inhibit cell wall biosynthesis by coordinating the d-Ala-d-Ala peptide termini of peptidoglycan precursors, disrupting peptidoglycan cross-linking.3,4 Strong binding to d-Ala-d-Ala results from a network of five hydrogen bonds along with hydrophobic interactions within the glycopeptide binding pocket (Figure 1).5–10 For a period after its discovery, vancomycin was considered the “antibiotic of last resort;” however, clinical resistance was first observed in the 1980s and has become increasingly prevalent since then.11–14 In an effort to combat resistant infections and better understand resistance mechanisms, synthetic chemists have generated a diverse range of vancomycin analogues through both semisynthesis15 and total synthesis.16,17

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of model ligand N,N’-Ac2-L-Lys-D-Ala-D-Ala bound to vancomycin.

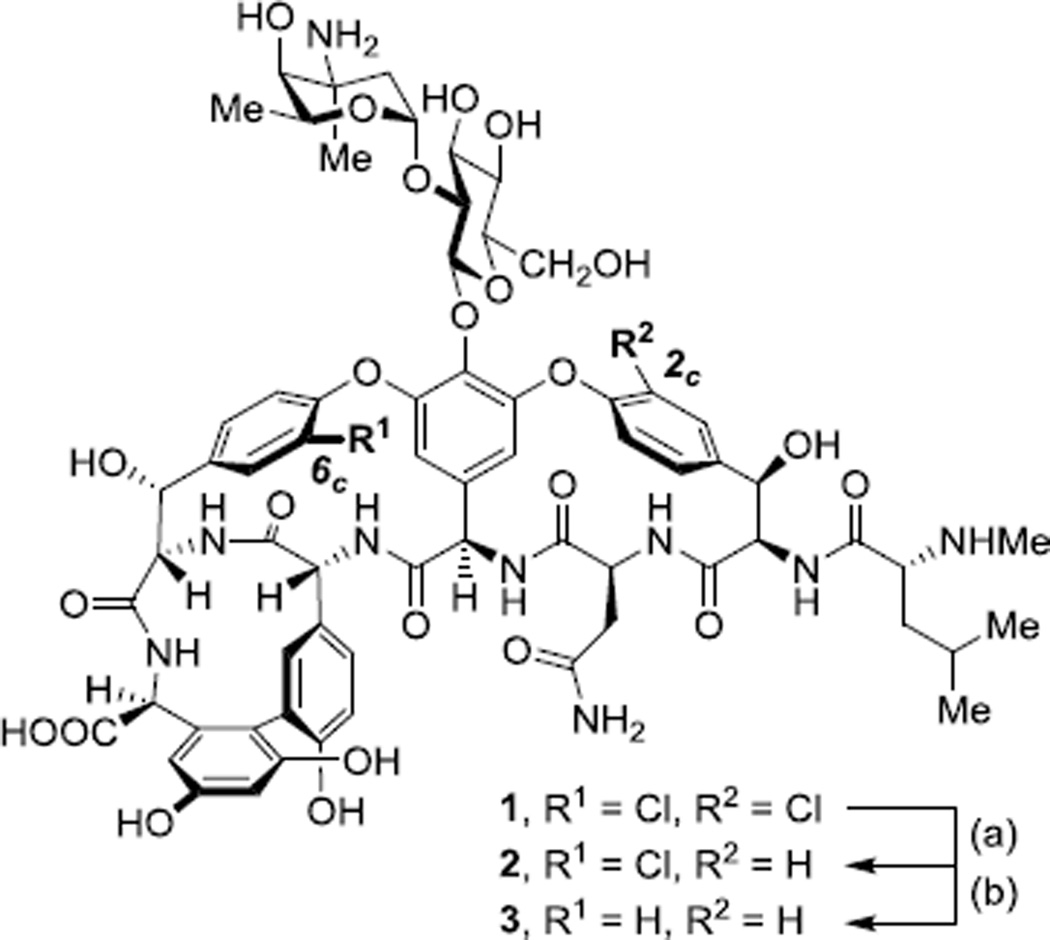

The 6c-Cl group (the “in-chloride”), located in vancomycin’s binding pocket, has inspired revealing studies over the past three decades. Harris and coworkers reported a method to prepare dechlorinated vancomycin derivatives via palladium-catalyzed hydrogenation and found 2c-Cl, oriented toward the convex face of the molecule, to be significantly more reactive than the in-chloride group.15a The authors prepared 2c-dechlorovancomycin (2) with 2c,6c-didechlorovancomycin (3) observed as the product of overreaction. More recently, Arimoto and coworkers utilized Suzuki-Miyaura (SM) coupling to access a library of 2c-functionalized and 2c,6c-difunctionalized vancomycin analogues, again observing substantially higher reactivity at 2c-Cl relative to 6c-Cl.15k Boger also reported an elegant 2c-borylation protocol that allowed unique access to organometallic substation reactions at the 2c-position.15l Moreover, although a synthesis of 6c-dechlorovancomycin has not yet been reported, Boger and coworkers recently prepared the aglycone of 6c-dechlorovancomycin, enabling binding studies and antibiotic measurements.15m

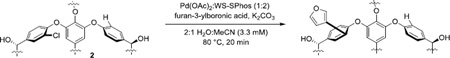

In recent years, our group has become interested in discovering approaches for the site-selective modification of vancomycin, and a single-step and site-selective synthesis of 6c-functionalized vancomycin has emerged as a goal.18 Toward this goal, we sought to better understand the reactivity of vancomycin’s 6c-Cl position absent the competing, more favorable, reaction at 2c-Cl under SM coupling conditions. We identified 2 as a suitable substrate for such studies, and a modified method based on that of Harris et al. was found to furnish 2 with minimal overreaction to 3 (Scheme 1).19 Furthermore, we anticipated that products resulting from such reactivity studies could possess increased biological activity and inspire future research efforts toward 6c-Cl modification. Herein, we report a stepwise dechlorination/cross-coupling strategy to access 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin derivatives and antibiotic evaluation of novel reaction products featuring diverse functionality at the in-chloride position.

Scheme 1.

Stepwise dechlorination of vancomycin (1). (a) 10% Pd/C, H2 (1 atm), H2O, rt, 3 h, 23%; (b) 10% Pd/C, H2 (4 atm), H2O, rt, 24 h, 75%.

Due to the substrate’s unique combination of reactivity, stability, and solubility properties, unusual challenges in the SM cross-coupling of 2 were encountered during reaction optimization. We found that aqueous conditions were required for substrate solubility, but that rapid decomposition of boronic acid coupling partners in water limited conversion.20–23 Additionally, product decomposition was unavoidable as a function of long reaction times; excess base (relative to boronic acid) was also found to accelerate this decomposition under the reaction conditions.24 The byproduct resulting from product decomposition was not identified; however, LCMS analysis revealed an identical isotope pattern to that of the product (see Supporting Information for more detail). Minimizing both types of decomposition (decomposition of boronic acid and decomposition of product) was found to be critical for efficient SM coupling of 2.

We began reaction optimization by investigating conditions utilizing high catalyst loading along with dropwise addition of a boronic acid/K2CO3 solution over a short reaction time (Table 1, Entry 1). Longer reaction times led to increased byproduct formation and lower product yield (Entry 2); yet, fewer equivalents of boronic acid and base led to decreased byproduct formation and higher product yield (Entry 3). We expected that dropwise addition of a boronic acid/K2CO3 solution would help avoid boronic acid decomposition and enable higher conversion; however, we observed nearly identical conversion upon switching to a “dump-and-stir” protocol (Entry 4; longer dropwise additions were not examined due to significant byproduct formation over longer reaction times). Next, we investigated conditions employing an excess of boronic acid relative to K2CO3 to further suppress base-promoted product decomposition, and a slight increase in product yield was, indeed, observed (Entry 5). Lower catalyst loading was also examined but afforded decreased yield due to low conversion, presumably because the slower coupling was unable to outcompete rapid boronic acid decomposition (Entries 6 and 7). Ultimately, the conditions in Entry 5 were best able to minimize decomposition of both boronic acid and product, leading to the highest product yield.

Table 1.

Representative optimization studies for the SM coupling of 2a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst (%) | Boronic acid (equiv.) |

K2CO3 (equiv.) |

Boronic acid/K2CO3 addition time (min) |

Starting material (%) | Product (%) | Byproduct (%) |

| 1 | 50 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 13 | 77 | 10 |

| 2b | 50 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 9 | 57 | 34 |

| 3 | 50 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 15 | 81 | 4 |

| 4 | 50 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 14 | 81 | 5 |

| 5 | 50 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 83 | 3 |

| 6 | 25 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 31 | 64 | 4 |

| 7b | 25 | 5 | 5 | 20 | 27 | 51 | 22 |

Yields represented by uncorrected HPLC integrations at 280 nm.

Reaction time = 60 min.

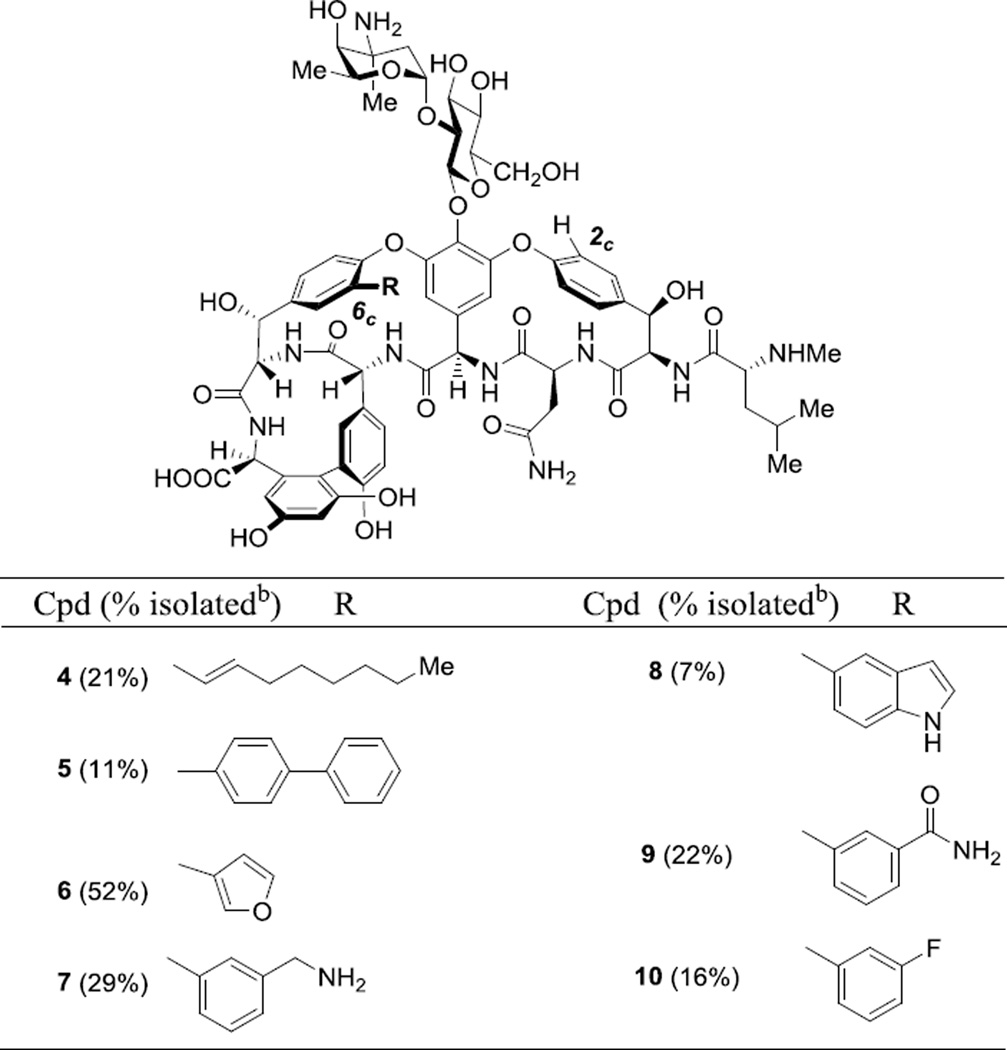

Once optimized SM reaction conditions were identified, a small library of 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin derivatives was prepared (Table 2). The antibiotic activities of vancomycin (1) and vancomycin derivatives 2–10 were then measured against vancomycin-sensitive S. aureus and E. faecalis strains and vancomycin-resistant strains of E. faecalis (VanA and VanB) using a standard microtiter plate-based antimicrobial assay (Table 3).25 In every case, 2 exhibited an approximately four-fold reduced activity compared to 1 (Entries 1 and 2), and the activity of 3 was reduced approximately eight-fold relative to 1 (Entries 1 and 3). These findings are consistent with those of Boger and coworkers, who measured similar reductions in activity against a vancomycin-sensitive strain of S. aureus for dechlorinated vancomycin aglycone derivatives relative to vancomycin aglycone.15l,15m In these prior studies, comparative binding of model cell wall ligands to 1–315a as well as dechlorovancomycin aglycone derivatives15l,15m suggested that the reduced antibiotic activity results from reduced binding efficiency between dechlorovancomycin analogues and cell wall precursors. The studies also indicate that decreases in binding affinity arising from dechlorination at 2c-Cl and 6c-Cl are additive in the case of 2c,6c-didechlorovancomycin analogues. Accordingly, the antibiotic activity of 2 is expected to be the most reliable baseline for comparison when considering the activities of novel 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin analogues 4–10.

Table 2.

Structures of 2cdechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin analogues.a

Optimized reaction conditions were employed for all compounds except 4 and 7, which required more forcing conditions. See Supporting Information for additional details.

Isolated yields refer to HPLC purified material that is chromatographically homogeneous for biological testing.

Table 3.

Antibiotic activity data (MIC, µg/mL) for 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin analogues against vancomycin-susceptible and vancomycin-resistant bacteria.a

| Entry | Compound | S. aureus (MSSA) | S. aureus (MRSA) | E. faecalis (VSE) | E. faecalis (VRE; VanB) | E. faecalis (VRE; VanA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | >64 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 64 | >64 |

| 3 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 32 | >64 | >64 |

| 4 | 4 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 5 | 5 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 6 | 6 | 64 | 64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 7 | 7 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 8 | 8 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 9 | 9 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 10 | 10 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

| 11 | Teicoplanin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 64 |

| 12 | Linezolid | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

MSSA = methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, ATCC 29213; MRSA = methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MMX 2002; VSE = vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis, MMX 101; VRE = vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis, VanB = MMX 202, VanA = MMX 486. See Supporting Information for additional details.

We observed that 6c-trans-1-octenyl (4) and 6c-(4-biphenyl) substitution (5) reduced activity beyond the threshold of the assay (>64 µg/mL) for all strains tested, including vancomycin-sensitive strains (Table 2, Entries 4–5). These observations are consistent with MIC measurements of 2c,6c-difunctionalized vancomycin derivatives against vancomycin-sensitive and vancomycin-resistant strains of S. aureus, E. faecium, and E. faecalis reported by Arimoto and coworkers.15k The authors found that larger hydrocarbon-based substituents (trans-1-octenyl and trans-(5-phenyl)-1-pentenyl) reduced activity beyond the detection threshold of 64 µg/mL while the relatively smaller substituent trans-1-propenyl displayed an activity similar to that of vancomycin. As observed in the present study, no compounds exhibited measurably increased activity against vancomycin-resistant strains. Taken with MIC data for dechlorovancomycin derivatives, our data re-assert that vancomycin’s antibiotic activity is highly sensitive to the binding pocket’s steric environment.

Nevertheless, we hypothesized that hydrogen-bonding, nucleophilic, or charged functionality at the 6c-position might increase biological activity through conformational changes or through noncovalent or covalent interactions with cell wall precursors. Compounds 6–10 were prepared and tested for their potential effects. While 6c-(3-furanyl)-substituted analogue 6 inhibits vancomycin-sensitive S. aureus strains at high concentration (64 µg/mL), inhibition was not detected for any E. faecalis strains examined (>64 µg/mL; Table 2, Entry 6). Interestingly, compounds bearing primary amino (7), indolyl (8), amido (9), and fluorophenyl (10) functionality all failed to inhibit any strains examined in this study (>64 µg/mL; Table 2, Entries 7–10). As observed with dechloro and hydrocarbon functionality at the 6c-position, steric constraints play the predominant role in determining the antibiotic activity of compounds 6–10 despite their diverse functionality. Indeed, the only example of these 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin analogues that possesses any measurable activity is furanyl derivative 6, which bears the smallest substituent at the 6c-position.

In summary, we have developed a generalizable, stepwise approach to access 2c-dechloro-6c-functionalized vancomycin derivatives, and MIC measurements of novel compounds have further advanced understanding of the binding pocket’s steric sensitivity. This stepwise approach will enable the preparation and evaluation of vancomycin derivatives beyond the scope of the present study. Selective chemical modification of the binding pocket of vancomycin continues to provide opportunities for creative analogue design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the United States National Institutes of Health (GM- 068649) for support. K.D.G. was partially supported by the Arthur Fleischer Award from Yale College.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at ________

References and notes

- 1.Williams DH, Bardsley B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1172. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990503)38:9<1172::AID-ANIE1172>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahne D, Leimkuhler C, Lu W, Walsh C. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:425. doi: 10.1021/cr030103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breukink E, de Kruijff B. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:321. doi: 10.1038/nrd2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Kruijff B, van Dam V, Breukink E. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids. 2008;79:117. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto M, Perkins HR. Biochem. J. 1971;123:789. doi: 10.1042/bj1230789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagarajan R. J. Antibiot. 1993;46:1181. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loll PJ, Bevivino AE, Korty BD, Axelsen PH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:1516. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vollmerhaus PJ, Breukink E, Heck AJR. Chem. Eur. J. 2003;9:1556. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McComas CC, Crowley BM, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9314. doi: 10.1021/ja035901x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia Z, O'Mara ML, Zuegg J, Cooper MA, Mark AE. FEBS J. 2013;280:1294. doi: 10.1111/febs.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugg TDH, Wright GD, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10408. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh CT, Fisher SL, Park IS, Prahalad M, Wu Z. Chem. Biol. 1996;3:21. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodford N. J. Med. Microbiol. 1998;47:849. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-10-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howden BP, Davies JK, Johnson PDR, Stinear TP, Grayson ML. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010;23:99. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00042-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Harris CM, Kannan R, Kopecka H, Harris TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:6652. [Google Scholar]; (b) Booth PM, Stone DJM, Williams DH. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1987:1694. [Google Scholar]; (c) Cooper RDG, Snyder NJ, Zweifel MJ, Staszak MA, Wilkie SC, Nicas TI, Mullen DL, Butler TF, Rodriguez MJ, Huff BE, Thompson RC. J. Antibiot. 1996;49:575. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pavlov AY, Lazhko EI, Preobrazhenskaya MN. J. Antibiot. 1997;50:509. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.50.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Thompson C, Ge M, Kahne D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1237. [Google Scholar]; (f) Nicolaou KC, Hughes R, Cho SY, Winssinger N, Smethurst C, Labischinski H, Endermann R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3823. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3823::AID-ANIE3823>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Nicolaou KC, Cho SY, Hughes R, Winssinger N, Smethurst C, Labischinski H, Endermann R. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:3798. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010903)7:17<3798::aid-chem3798>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Nicolaou KC, Hughes R, Cho SY, Winssinger N, Labischinski H, Endermann R. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:3824. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010903)7:17<3824::aid-chem3824>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Kim SJ, Matsuoka S, Patti GJ, Schaefer J. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3822. doi: 10.1021/bi702232a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Crane CM, Boger DL. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:1471. doi: 10.1021/jm801549b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Nakama Y, Yoshida O, Yoda M, Araki K, Sawada Y, Nakamura J, Xu S, Miura K, Maki H, Arimoto H. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2528. doi: 10.1021/jm9017543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Pinchman JR, Boger DL. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:4116. doi: 10.1021/jm4004494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Pinchman JR, Boger DL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:4817. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Evans DA, Wood MR, Trotter BW, Richardson TI, Barrow JC, Katz JL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2700. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2700::AID-ANIE2700>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Takayanagi M, Jain NF, Natarajan S, Koumbis AE, Bando T, Ramanjulu JM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2717. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2717::AID-ANIE2717>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nicolaou KC, Mitchell HJ, Jain NF, Winssinger N, Hughes R, Bando T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:240. [Google Scholar]; (d) Nicolaou KC, Li H, Boddy CNC, Ramanjulu JM, Yue T-Y, Natarajan S, Chu X-J, Bräse S, Rübsam F. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:2584. [Google Scholar]; (e) Nicolaou KC, Boddy CNC, Li H, Koumbis AE, Hughes R, Natarajan S, Jain NF, Ramanjulu JM, Bräse S, Solomon ME. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:2602. [Google Scholar]; (f) Nicolaou KC, Koumbis AE, Takayanagi M, Natarajan S, Jain NF, Bando T, Li H, Hughes R. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:2622. [Google Scholar]; (g) Nicolaou KC, Mitchell HJ, Jain NF, Bando T, Hughes R, Winssinger N, Natarajan S, Koumbis AE. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:2648. [Google Scholar]; (h) Boger DL, Miyazaki S, Kim SH, Wu JH, Castle SL, Loiseleur O, Jin Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:10004. [Google Scholar]; (i) Crowley BM, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2885. doi: 10.1021/ja0572912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Xie J, Pierce JG, James RC, Okano A, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13946. doi: 10.1021/ja207142h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Xie J, Okano A, Pierce JG, James RC, Stamm S, Crane CM, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1284. doi: 10.1021/ja209937s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For reviews, see Nicolaou KC, Boddy CNC, Bräse S, Winssinger N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:2096. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19990802)38:15<2096::aid-anie2096>3.0.co;2-f. Boger DL. Med. Res. Rev. 2001;21:356. doi: 10.1002/med.1014. Zhanel G, Calic D, Schweizer F, Zelenitsky S, Adam H, Lagacé-Wiens PS, Rubinstein E, Gin A, Hoban D, Karlowsky J. Drugs. 2010;70:859. doi: 10.2165/11534440-000000000-00000. James RC, Pierce JG, Okano A, Xie J, Boger DL. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:797. doi: 10.1021/cb300007j.

- 18.(a) Fowler BS, Laemmerhold KM, Miller SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9755. doi: 10.1021/ja302692j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pathak TP, Miller SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6120. doi: 10.1021/ja301566t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pathak TP, Miller SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8415. doi: 10.1021/ja4038998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Han S, Miller SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12414. doi: 10.1021/ja406067v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Han S, Le BV, Hajare HS, Baxter RHG, Miller SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:8550. doi: 10.1021/jo501625f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yoganathan S, Miller SJ. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:2367. doi: 10.1021/jm501872s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The procedure of Ref 15a was modified by truncation of reaction time, lower Pd/C loading, and reduced H2 pressure to avoid didechlorination. See Supporting Information for further details.

- 20.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2457. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Littke AF, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:4176. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4176::AID-ANIE4176>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson KW, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6173. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lennox AJJ, Lloyd-Jones GC. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:412. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60197h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.As summarized in Ref 15l: “Reactions involving high temperatures (>100 °C) are known to cause rearrangements, isomerizations, and retro-aldol side reactions. Strong bases can further lead to additional degradation”.

- 25.Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by Micromyx, LLC (Kalamazoo, MI) in accordance with CLSI guidelines. See Supporting Information for further details.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.