Abstract

Primary intracranial malignant melanoma is a very rare and highly aggressive tumor with poor prognosis. A 66-year-old female patient presented a headache that had been slowly progressing for several months. A large benign pigmented skin lesion was found on her back. A brain MRI showed multiple linear signal changes with branching pattern and strong enhancement in the temporal lobe. The cytological and immunohiostochemical cerebrospinal fluid examination confirmed malignant melanoma. A biopsy confirmed that the pigmented skin lesion on the back and the conjunctiva were benign nevi. We report a case of primary intracranial malignant melanoma and review relevant literatures.

Keywords: Primary, Melanoma, CNS, Subarachnoid hemorrhage, Leptomeninges

INTRODUCTION

Melanoma can occur in any part of the body that has melanocytes. However, it usually develops in the skin, mucosa, and choroid in the eye. In the central nervous system (CNS), melanocytes normally exist in the leptomeninges located on the inferior surface of the cerebrum and, the anterolateral surface of the brainstem and the spinal cord. Melanocytic lesions of CNS include melanocytosis, melanomatosis, melanocytoma, and malignant melanoma. Melanocytosis and melanomatosis are benign and involve diffusely leptomeninges and superficial brain parenchyma, which generally occur in the setting of dermatologic syndrome8). Melanocytoma is a solitary, benign and low-grade tumor that occurs mostly in the intradural extramedullary cervical or thoracic spine5). Malignant melanoma is a highly aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis, which arises from melanoblasts6). Secondary or metastatic intracranial malignant melanoma is frequent in patients with disseminated melanomas. However, primary intracranial leptomeningeal melanomatosis, also known as a meningeal variant of primary intracranial malignant melanoma is rare. Its rarity may contribute to the high chance of misdiagnosis, especially in the cases without skin lesions. We report a rare case of primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis and review relevant literatures.

CASE REPORT

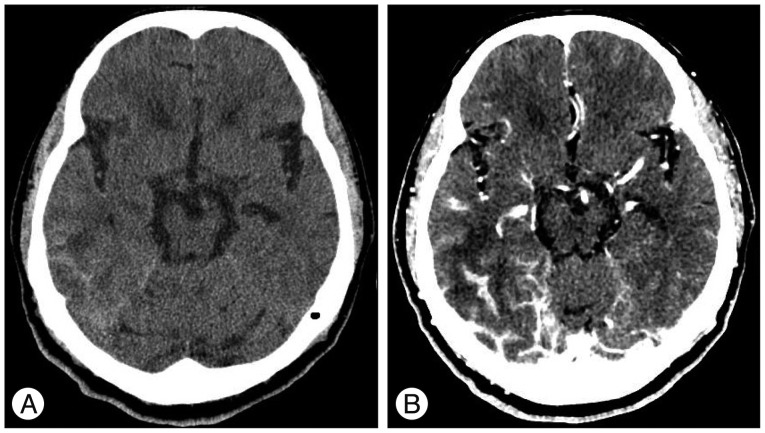

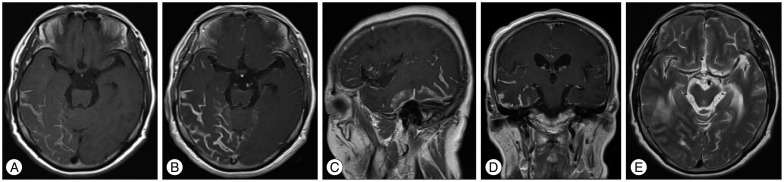

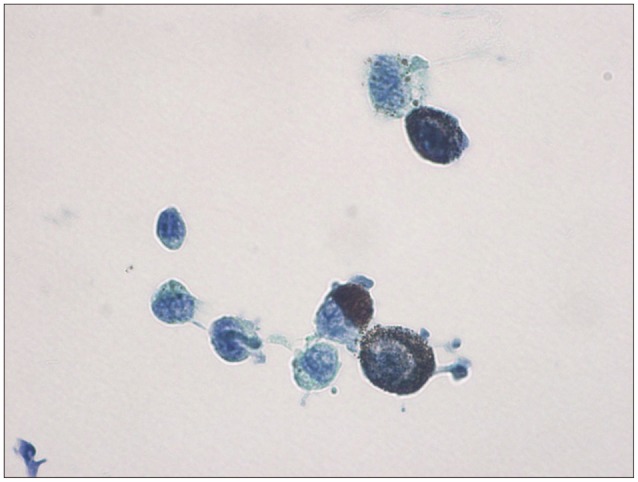

A 66-year-old female patient presented a headache that had been progressing over several months. The neurological examinations showed no specific neurological deficits. The brain computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1) showed diffuse high density lesions with multiple, branching, and linear enhancements in the base of the right temporal lobe. These non-contrast CT findings were similar to those of subarachnoid hemorrhages (SAH). The brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) (Fig. 2) revealed multiple, branching, and linear high signal intensity lesions on the T1-weighted image (WI), low signal intensity lesions on the T2-WI, and strong enhancements with the same pattern. Spinal tapping for cytological examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was performed to rule out hemorrhage, infectious diseases and tumors. The cytological examination showed high cellularity, pleomorphic cells with abundant cytoplasm and black pigmentation, nuclear pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and seven mitoses per 10 high power fields (HPFs). These tumor cells showed strong immunoreactivity to HMB-45, S-100, and Melan-A. These histopathological findings are compatible with those of malignant melanoma (Fig. 3). The whole body positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT) showed no abnormal findings. A biopsy showed that the pigmented skin lesions on the back and the conjunctiva (Fig. 4) were benign pigmented nevi.

Fig. 1. Brain CT shows diffuse high density lesion in the base of right temporal lobe which is similar finding with subarachnoid hemorrhage on non-contrast image (A). Strong enhancements with multiple, branching, linear pattern are seen in the same area (B).

Fig. 2. Brain MRI shows multiple, branching, linear high signal intensity lesions in the right temporal base on axial T1-WI (A), and also strong enhancements with same pattern are seen (B). These findings are mainly found in the lateral and inferior surfaces of the temporal lobe on enhanced sagittal (C) and coronal T1-WIs (D). Low signal intensity lesions with same patterns are seen in the same location on axial T2-WI (E).

Fig. 3. Pathological findings shows pleomorphic cells with abundant cytoplasm, abundant intracytoplasmic melanin pigments, nuclear pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli (Papanicolaou stain, ×1000). These tumor cells showed strong immunoreactivity to HMB-45, S-100, and Melan-A on the immunohistochemical study.

Fig. 4. Photograph of skin lesion on the back. This lesion was confirmed as pigmented nevi through the biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Primary CNS melanoma is rare, with only an approximately 1% incidence of all cases of melanomas2) whereas secondary intracranial melanomas are common. Melanocytes are derived from melanoblasts, which originate from the neural crest of the neuroectoderm during the embryonic period6). Malignant transformation of preexisting melanocytic precursor cells is considered the etiology of melanocytic tumors1,11).

Primary CNS melanocytic tumors can radiologically present a localized or nodular pattern and a diffuse or infiltrating pattern. The diffuse type is called melanomatosis, which represents diffuse infiltrations into the subarachnoid space and the superficial brain without a solid mass2). The focal type is called melanocytoma, which is limited to a circumscribed pigmented mass. It has a better prognosis than the diffuse type because of the possibility of total excision by surgery2).

In this case, diffuse enhancements were found in the temporal lobe without definite mass and the cytological examination for CSF confirmed malignancy. Primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis, which is the diffuse variant of primary CNS malignant melanoma, is rare and has a poor prognosis. It results from the diffuse spreading of malignant melanocytes into the leptomeninges and superficial invasion of the brain10). It usually appears in children and may be part of neurocutaneous melanosis or phakomas12). Leptomeningeal melanomatosis can present symptoms of increased intracranial pressure or compression of the neural structures, depending on its location. On the CT, it showed a high density lesion with marginal enhancement. The non-contrast CT findings in this case was similar those of SAH although the results of the neurological examinations are irrelevant to them. Therefore, we thought a CSF study might be needed for differential diagnosis.

On the MRI, they showed hyper-intensity on the T1 and hypo-intensity on the T2-WI because the paramagnetic effect of the melanin, which has stable organic free radicals inside it, results in shortens both the T1 and T2 relaxation times in typical melanotic melanoma12). On the other hand, amelanotic melanoma shows iso to hypointensity on the T1 and moderately hyperintensity on the T2-WI. It should also be remembered that signal changes can vary depending on the presence of acute or chronic intra-tumoral bleeding. The MR findings in this case were similar to those of melanotic melanoma without intra-tumoral bleedings. Because of the typical signal changes on the MRI, we should be aware of the diagnosis especially of primary CNS melanoma.

Primary CNS melanoma can be diagnosed when there is no melanoma outside the CNS, and when it is immunohistochemically confirmed in the specimens. Hayward3) described primary CNS melanoma as follows : no malignant melanoma outside the CNS, an absence of this lesion in another area of the CNS, and histo-pathological confirmation.

Histologically, primary CNS melanomas show considerable pleomorphism, large bizarre tumor cells that include multinucleated giant cells, and a variable amount of melanin pigment. High mitotic rates, necrosis, hemorrhages, and invasion of the neural parenchyme are also common. Leptomeningeal melanosis that presents diffuse proliferation of nevoid polygonal melanocytes in the leptomeninges lack the overt cytological atypia or frank brain invasion10). An immunohistochemical study showed that 86–97% of these tumors test positive for expression of HMB-45, an antibody with higher specificity for melanocytic tumors2). S-100 protein is found in almost all melanocytic tumors, but is also present in other neural crest origin tumors. Their expression can also be observed in several non-melanocytic tumors that include malignant schwannoma, gliosarcoma, and metastatic carcinoma. Most cases of melanoma have been reported to be Melan-A positive12). Therefore, melanoma can be definitively diagnosed through a biopsy and an immunochemical study. Also, when CSF dissemination of melanoma is suspected, a cytological examination of the CSF with an immunohistochemical study can confirm the diagnosis. Several cytogenetic studies have shown structural aberrations of chromosome 6 which are also seen in both primary and secondary malingnant melanoma8). Thus, it is difficult to differentiate primary malignant melanoma from the secondary type through a cytogenetic study. Primary leptomeningeal melanomatosis can be radiologically confused with intracranial hypotension syndrome, various infectious diseases, diffuse infiltrating hematopoietic cancers, diffuse infiltrating metastasis10). Other CNS tumors, such as pigmented schwannomas, meningiomas, medulloblastomas, paragangliomas, and various gliomas can undergo melanization9).

Complete surgical excision, if possible, is the best treatment, because melanoma is a highly aggressive, radioresistant tumor with a poor prognosis. However, in cases of totally excised melanomas, the prognosis is quite good with the postoperative survival times ranging from one to 28 years4). Extracranial metastasis to lung, spleen, pancreas, and kidney has rarely been reported6). The role and efficacy of radiotherapy and chemotherapy remain controversial7).

CONCLUSION

Primary CNS melanoma can be difficult to diagnose in the preoperative clinical field due to its rare incidence especially in the cases without any cutaneous manifestation. Histopathological examination of primary CNS lesion or cerebrospinal fluid, immunohistochemical study, and early awareness of melanomas can yeild a definitive diagnosis.

References

- 1.Gempt J, Buchmann N, Grams AE, Zoubaa S, Schlegel J, Meyer B, et al. Black brain : transformation of a melanocytoma with diffuse melanocytosis into a primary cerebral melanoma. J Neurooncol. 2011;102:323–328. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greco Crasto S, Soffietti R, Bradac GB, Boldorini R. Primitive cerebral melanoma : case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:163–168. discussion 168. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(01)00348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayward RD. Malignant melanoma and the central nervous system. A guide for classification based on the clinical findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:526–530. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.6.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibáñez J, Weil B, Ayala A, Jimenez A, Acedo C, Rodrigo I. Meningeal melanocytoma : case report and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1997;30:576–581. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.5660798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaiswal S, Vij M, Tungria A, Jaiswal AK, Srivastava AK, Behari S. Primary melanocytic tumors of the central nervous system : a neuroradiological and clinicopathological study of five cases and brief review of literature. Neurol India. 2011;59:413–419. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.82758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jellinger K, Chou P, Paulus W. Melanocytic lesions. In: Kleihues P, Cavanee WK, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CJ, Rhee DY, Heo W, Park HS. Primary leptomeningeal malignant melanoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2004;36:425–427. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piedra MP, Scheithauer BW, Driscoll CL, Link MJ. Primary melanocytic tumor of the cerebellopontine angle mimicking a vestibular schwannoma : case report. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:E206, discussion E206. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000219236.48886.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pirini MG, Mascalchi M, Salvi F, Tassinari CA, Zanella L, Bacchini P, et al. Primary diffuse meningeal melanomatosis : radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:115–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roser F, Nakamura M, Brandis A, Hans V, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Transition from meningeal melanocytoma to primary cerebral melanoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:528–531. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.3.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah I, Imran M, Akram R, Rafat S, Zia K, Emaduddin M. Primary intracranial malignant melanoma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]