Abstract

Background

The Great East Japan Earthquake inflicted severe damage on the Pacific coastal areas of northeast Japan. Although possible health impacts on aged or handicapped populations have been highlighted, little is known about how the serious disaster affected preschool children’s health. We conducted a nationwide nursery school survey to investigate preschool children’s physical development and health status throughout the disaster.

Methods

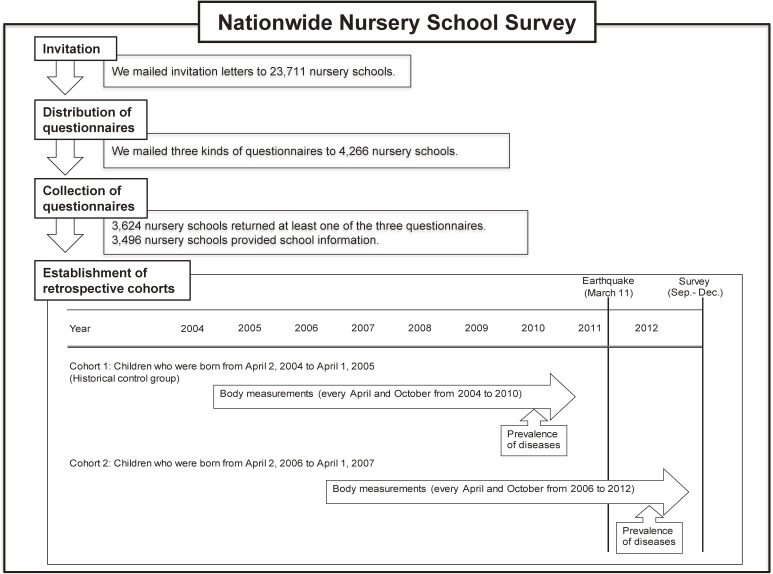

The survey was conducted from September to December 2012. We mailed three kinds of questionnaires to nursery schools in all 47 prefectures in Japan. Questionnaire “A” addressed nursery school information, and questionnaires “B1” and “B2” addressed individuals’ data. Our targets were children who were born from April 2, 2004, to April 1, 2005 (those who did not experience the disaster during their preschool days) and children who were born from April 2, 2006, to April 1, 2007 (those who experienced the disaster during their preschool days). The questionnaire inquired about disaster experiences, anthropometric measurements, and presence of diseases.

Results

In total, 3624 nursery schools from all 47 prefectures participated in the survey. We established two nationwide retrospective cohorts of preschool children; 53 747 children who were born from April 2, 2004, to April 1, 2005, and 69 004 children who were born from April 2, 2006, to April 1, 2007. Among the latter cohort, 1003 were reported to have specific personal experiences with the disaster.

Conclusions

With the large dataset, we expect to yield comprehensive study results about preschool children’s physical development and health status throughout the disaster.

Key words: natural disaster, preschool children, physical development, children’s health, retrospective cohort

Abstract

背景:

東日本大震災(以下、大震災)は東北を中心とした東日本の太平洋沿岸地域に甚大な被害をもたらした。高齢者や障害者の健康への影響が懸念される一方で、震災が未就学児の健康へ及ぼす影響については殆ど知られていない。そこで、大震災前後における未就学児の身体発育と健康状態を調査するために全国保育所調査を実施した。

方法:

調査は、2012年9月から12月に実施した。全国47都道府県の保育所に3種類の調査票を郵送した。調査票Aでは保育所の状況を、調査票B1とB2では、園児の情報を収集した。対象は、2004年4月2日から2005年4月1日生まれの子ども‐保育所在園中に大震災を経験しなかった子ども‐、2006年4月2日から2007年4月1日生まれの子ども‐保育所在園中に大震災を経験した子ども‐である。調査項目は、被災経験、身体計測値、疾患の有無である。

結果:

全国から3,624保育所が調査に参加した。その結果、2004年4月2日から2005年4月1日生まれの子ども53,747人と2006年4月2日から2007年4月1日生まれの子ども69,004人の2つの後ろ向きコホートを確立した。後者の中で、1,003名には、家屋の損壊、津波、避難所生活等の被災体験があった。

結論:

得られた大規模なデータをもとに、大震災前後における未就学児の身体発育と健康状態に関する研究成果が期待される。

キーワード: 東日本大震災, 未就学児, 身体発育, 小児保健, 後ろ向きコホート研究

INTRODUCTION

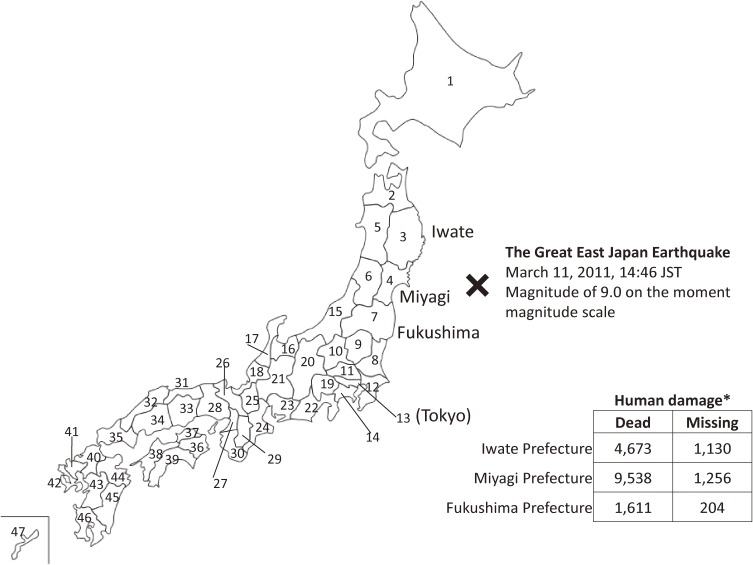

The Great East Japan Earthquake, which occurred on March 11, 2011, was beyond our experience in modern Japanese history. The massive 9.0 magnitude earthquake was the largest quake ever recorded in Japan, and the following giant tsunami inflicted severe damage on the Pacific coastal areas of northeast Japan.1–5 The number of deaths and missing persons due to the disaster was 18 412 across Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures (Figure 1).6 Furthermore, the earthquake caused a nuclear alert in the vicinity of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.7–10

Figure 1. Geographic location affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake.The numbers on the map indicate prefecture codes corresponding to those in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 4.*The human damage number shows dead and missing persons in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures that were the most seriously affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake (The numbers are cited from Japan Meteorological Agency and National Police Agency).

Previous studies have reported health issues among the survivors and have focused attention on vulnerable populations, including the elderly, disabled, and hospitalized patients.11–15 Children are also vulnerable, but there has been little research documenting their health after the disaster.

In order to investigate the possible health impacts of the devastating natural disaster on preschool children, we conducted a nationwide nursery school survey. The survey should provide comprehensive and valuable epidemiological evidence of the impact of the disaster on preschool children, focusing on the differences in physical development before and after the disaster and assessing the extent to which experiencing the disaster, including environmental changes due to the disaster, may influence children’s health. This paper describes the design of the survey and the results of data collection.

METHODS

Survey design and population

We collected data on nursery school children not only from the most seriously affected areas of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures, but also from other areas across Japan. In the present survey, the prefectures indicate the location of the nursery schools that children were attending at the time of the survey. Prior to the survey, invitation letters were distributed to 23 711 authorized nursery schools,16 and 4266 (18%) nursery schools expressed interest in participating in the survey. From September to December 2012, we mailed three kinds of questionnaires to the 4266 nursery schools, and nursery teachers completed the questionnaires and mailed them back to the coordination office at Tohoku University.

The new school term in Japan starts on April 1, and a class consists of children who are born from April 2 to April 1 of the following year.17 We targeted children who were born in two classes: children who were born from April 2, 2004, to April 1, 2005, who were in the 5-year-old class of 2010 and did not experience the disaster during their preschool days; and children who were born from April 2, 2006, to April 1, 2007, who were in the 5-year-old class of 2012 and experienced the disaster during their preschool days (47 to 59 months of age when the disaster occurred). We defined the former group of children as a historical control group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flow of the Nationwide Nursery School Survey.

Measurements

Questionnaire “A” addressed information on each nursery school: name of the nursery school, whether or not the nursery school was affected by the disaster, and the damage sustained in the disaster (collapse of the building, tsunami, fire, relocation of the nursery school, and others), if affected. Additionally, we asked for teachers’ subjective opinion through the question: “Do you think that experiencing the disaster influenced children’s development?” with an open-ended question about possible factors that might affect children’s development (eAppendix 1).

Questionnaires “B1” and “B2” addressed individual data on children who were born from April 2, 2004, to April 1, 2005 and those who were born from April 2, 2006, to April 1, 2007, respectively. Both anonymous questionnaires included questions about sex, year and month of birth, presence of diseases diagnosed by medical doctors (kidney disease, heart disease, atopic dermatitis, bronchial asthma, and others), history of moving in and moving out, and anthropometric measurements. According to the guidelines for childcare in nursery school, all nursery schools have to periodically perform physical measurements (generally every month) using a measurement procedure recommended by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.18 Considering the seasonal variation in growth, we retrospectively collected individuals’ height and weight measured in April and October for a maximum of 7 years. Additionally, we inquired about personal disaster experience with the following options: collapse of house, tsunami, fire, moving house, evacuation center, and death of a family member (eAppendix 2 and eAppendix 3).

Ethical considerations

The survey protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Tohoku University. We collected only existing data, so we did not obtain informed consent from participants in either cohort. In accordance with the national Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research, we disclosed information regarding the survey in two ways: we announced the conduct of the survey to parents using a poster displayed in each nursery school, and we disclosed the survey information, including the significance, objective, and methods of the survey, to the public on the website of Tohoku University’s School of Medicine at http://www.med.tohoku.ac.jp/public/ekigaku2013.html. Parents had the right to opt out.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, nursery schools from all 47 prefectures participated in the survey. Of the nursery schools that agreed to participate in the survey, 3624 returned at least one of the three questionnaires. We acquired school information from 3495 nursery schools. We obtained individuals’ data for 54 558 children who were born from April 2, 2004, to April 1, 2005 (historical controls), and 69 702 children who were born from April 2, 2006, to April 1, 2007 (exposed children). As an initial data cleaning step, we excluded data on children who were born in a different year and those whose anthropometric measurements were not provided, leaving totals of 53 747 historical controls and 69 004 exposed children eligible for the initial dataset (Table 2).

Table 1. Proportion of nursery schools that participated in the survey.

| Prefecture | Number of nursery schools | Proportion | ||

| Code | Name | Target (n = 23 711) | Participationb (n = 3624) | |

| 1 | Hokkaido | 855 | 139 | 16% |

| 2 | Aomori | 470 | 108 | 23% |

| 3 | Iwatea | 359 | 81 | 23% |

| 4 | Miyagia | 346 | 132 | 38% |

| 5 | Akita | 254 | 88 | 35% |

| 6 | Yamagata | 241 | 42 | 17% |

| 7 | Fukushimaa | 317 | 97 | 31% |

| 8 | Ibaraki | 489 | 53 | 11% |

| 9 | Tochigi | 353 | 79 | 22% |

| 10 | Gunma | 418 | 62 | 15% |

| 11 | Saitama | 993 | 164 | 17% |

| 12 | Chiba | 790 | 142 | 18% |

| 13 | Tokyo | 1855 | 204 | 11% |

| 14 | Kanagawa | 1142 | 120 | 11% |

| 15 | Niigata | 709 | 156 | 22% |

| 16 | Toyama | 303 | 62 | 20% |

| 17 | Ishikawa | 361 | 50 | 14% |

| 18 | Fukui | 272 | 40 | 15% |

| 19 | Yamanashi | 231 | 37 | 16% |

| 20 | Nagano | 586 | 60 | 10% |

| 21 | Gifu | 425 | 42 | 10% |

| 22 | Shizuoka | 510 | 98 | 19% |

| 23 | Aichi | 1209 | 237 | 20% |

| 24 | Mie | 477 | 77 | 16% |

| 25 | Shiga | 208 | 21 | 10% |

| 26 | Kyoto | 481 | 23 | 5% |

| 27 | Osaka | 1236 | 95 | 8% |

| 28 | Hyogo | 893 | 77 | 9% |

| 29 | Nara | 192 | 25 | 13% |

| 30 | Wakayama | 210 | 10 | 5% |

| 31 | Tottori | 191 | 29 | 15% |

| 32 | Shimane | 286 | 45 | 16% |

| 33 | Okayama | 403 | 106 | 26% |

| 34 | Hiroshima | 615 | 132 | 21% |

| 35 | Yamaguchi | 310 | 53 | 17% |

| 36 | Tokushima | 216 | 13 | 6% |

| 37 | Kagawa | 209 | 41 | 20% |

| 38 | Ehime | 320 | 49 | 15% |

| 39 | Kochi | 258 | 44 | 17% |

| 40 | Fukuoka | 905 | 144 | 16% |

| 41 | Saga | 248 | 23 | 9% |

| 42 | Nagasaki | 438 | 67 | 15% |

| 43 | Kumamoto | 587 | 88 | 15% |

| 44 | Oita | 280 | 37 | 13% |

| 45 | Miyazaki | 394 | 66 | 17% |

| 46 | Kagoshima | 473 | 48 | 10% |

| 47 | Okinawa | 393 | 18 | 5% |

aThe three prefectures that were most severely affected by the earthquake include Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures.

bWe defined participation as returning at least one questionnaire from Questionnaire “A,” Questionnaire “B1,” and Questionnaire “B2.”

Table 2. Number of completed questionnaires returned from nursery schools.

| Prefecture | Questionnaire A: Questions regarding nursery school |

Questionnaire B1: Questions for children born from April 2, 2004 to April 1, 2005 |

Questionnaire B2: Questions for children born from April 2, 2006 to April 1, 2007 |

|

| Code | Name | (n = 3495)b | (n = 53 747) | (n = 69 004) |

| 1 | Hokkaido | 137 | 1665 | 2087 |

| 2 | Aomori | 105 | 1135 | 1485 |

| 3 | Iwatea | 78 | 906 | 1248 |

| 4 | Miyagia | 126 | 1804 | 2390 |

| 5 | Akita | 87 | 1463 | 1745 |

| 6 | Yamagata | 41 | 628 | 748 |

| 7 | Fukushimaa | 97 | 1004 | 1557 |

| 8 | Ibaraki | 53 | 770 | 1137 |

| 9 | Tochigi | 77 | 1116 | 1519 |

| 10 | Gunma | 61 | 1180 | 1223 |

| 11 | Saitama | 155 | 2429 | 3235 |

| 12 | Chiba | 138 | 2488 | 3228 |

| 13 | Tokyo | 190 | 2573 | 4019 |

| 14 | Kanagawa | 118 | 2031 | 2551 |

| 15 | Niigata | 154 | 2020 | 3008 |

| 16 | Toyama | 61 | 1068 | 1092 |

| 17 | Ishikawa | 49 | 903 | 999 |

| 18 | Fukui | 39 | 408 | 580 |

| 19 | Yamanashi | 37 | 720 | 706 |

| 20 | Nagano | 55 | 1143 | 1292 |

| 21 | Gifu | 42 | 927 | 1096 |

| 22 | Shizuoka | 90 | 1886 | 2146 |

| 23 | Aichi | 231 | 5121 | 5588 |

| 24 | Mie | 73 | 1112 | 1437 |

| 25 | Shiga | 21 | 427 | 535 |

| 26 | Kyoto | 22 | 407 | 458 |

| 27 | Osaka | 91 | 1611 | 2273 |

| 28 | Hyogo | 72 | 1013 | 1464 |

| 29 | Nara | 25 | 334 | 500 |

| 30 | Wakayama | 9 | 178 | 201 |

| 31 | Tottori | 29 | 354 | 577 |

| 32 | Shimane | 45 | 482 | 699 |

| 33 | Okayama | 104 | 1778 | 2105 |

| 34 | Hiroshima | 125 | 2522 | 2982 |

| 35 | Yamaguchi | 51 | 534 | 853 |

| 36 | Tokushima | 12 | 157 | 156 |

| 37 | Kagawa | 40 | 462 | 753 |

| 38 | Ehime | 48 | 508 | 615 |

| 39 | Kochi | 43 | 653 | 763 |

| 40 | Fukuoka | 139 | 2571 | 3145 |

| 41 | Saga | 22 | 354 | 418 |

| 42 | Nagasaki | 65 | 647 | 770 |

| 43 | Kumamoto | 80 | 995 | 1336 |

| 44 | Oita | 36 | 311 | 467 |

| 45 | Miyazaki | 59 | 415 | 905 |

| 46 | Kagoshima | 46 | 452 | 774 |

| 47 | Okinawa | 17 | 82 | 139 |

aThe three prefectures that were most severely affected by the earthquake include Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures.

bTotal number was not equal to 3624 as described in Table 1 because 129 nursery schools did not return Questionnaire “A.”

Table 3 briefly summarizes the characteristics of each cohort. The two cohorts were similar in distributions of sex, birth month, and presence of diseases diagnosed by medical doctors. Among children who experienced the disaster during their preschool days, 1003 (1.5%) were reported to have specific personal experiences with the disaster.

Table 3. Characteristics of nursery school children.

| Children born from April 2, 2004 to April 1, 2005 |

Children born from April 2, 2006 to April 1, 2007 |

P | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | 0.31 | ||||

| Boy | 27 823 | 51.8% | 35 536 | 51.5% | |

| Girl | 25 449 | 47.3% | 32 884 | 47.7% | |

| Missing | 475 | 0.9% | 584 | 0.8% | |

| Birth month | 0.58 | ||||

| April | 4556 | 8.5% | 5657 | 8.2% | |

| May | 4562 | 8.5% | 5968 | 8.6% | |

| June | 4404 | 8.2% | 5733 | 8.3% | |

| July | 4748 | 8.8% | 5992 | 8.7% | |

| August | 4676 | 8.7% | 5946 | 8.6% | |

| September | 4680 | 8.7% | 6028 | 8.7% | |

| October | 4405 | 8.2% | 5693 | 8.3% | |

| November | 4294 | 8.0% | 5642 | 8.2% | |

| December | 4361 | 8.1% | 5682 | 8.2% | |

| January | 4482 | 8.3% | 5680 | 8.2% | |

| February | 3771 | 7.0% | 4801 | 7.0% | |

| March | 4221 | 7.9% | 5528 | 8.0% | |

| April (following year) | 110 | 0.2% | 114 | 0.2% | |

| Missing | 477 | 0.9% | 540 | 0.8% | |

| Presence of diseases diagnosed by medical doctors | 0.28 | ||||

| No | 44 380 | 82.6% | 58 462 | 84.7% | |

| Yes | 6064 | 11.3% | 7832 | 11.4% | |

| Unknown | 307 | 0.6% | 342 | 0.5% | |

| Missing | 2996 | 5.6% | 2368 | 3.4% | |

| Experience of the disaster | |||||

| No | N/A | 62 244 | 90.2% | ||

| Yes | N/A | 1003 | 1.5% | ||

| Missing | N/A | 5757 | 8.3% | ||

| (Specific experience) | |||||

| Collapse of house | 366 | ||||

| Tsunami | 224 | ||||

| Fire | 3 | ||||

| Moving house | 189 | ||||

| Evacuation right | 279 | ||||

| Death of family member | 31 | ||||

Differences in sex, birth month, and presence of diseases between two cohorts were tested by chi-square tests.

Table 4 presents the residential distribution of children with personal disaster experiences based on the location of the nursery schools that children were attending at the time of the survey. While 732 children (73.0%) were residing in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures, 271 (27.0%) were residing in various parts of the country other than the three affected prefectures.

Table 4. Residential distribution of children with personal disaster experiences.

| Prefecture | Disaster experience | ||

| Code | Name | No (n = 62 244) | Yes (n = 1003) |

| 1 | Hokkaido | 1911 | 4 |

| 2 | Aomori | 1372 | 14 |

| 3 | Iwatea | 1094 | 96 |

| 4 | Miyagia | 1727 | 351 |

| 5 | Akita | 1650 | 8 |

| 6 | Yamagata | 665 | 31 |

| 7 | Fukushimaa | 1116 | 285 |

| 8 | Ibaraki | 983 | 78 |

| 9 | Tochigi | 1395 | 6 |

| 10 | Gunma | 1101 | 5 |

| 11 | Saitama | 2942 | 11 |

| 12 | Chiba | 2987 | 41 |

| 13 | Tokyo | 3825 | 10 |

| 14 | Kanagawa | 2357 | 4 |

| 15 | Niigata | 2709 | 12 |

| 16 | Toyama | 984 | 0 |

| 17 | Ishikawa | 868 | 1 |

| 18 | Fukui | 551 | 0 |

| 19 | Yamanashi | 669 | 2 |

| 20 | Nagano | 1136 | 4 |

| 21 | Gifu | 985 | 0 |

| 22 | Shizuoka | 1966 | 3 |

| 23 | Aichi | 4974 | 7 |

| 24 | Mie | 1258 | 1 |

| 25 | Shiga | 489 | 1 |

| 26 | Kyoto | 402 | 0 |

| 27 | Osaka | 2063 | 2 |

| 28 | Hyogo | 1342 | 2 |

| 29 | Nara | 489 | 1 |

| 30 | Wakayama | 198 | 0 |

| 31 | Tottori | 552 | 1 |

| 32 | Shimane | 669 | 0 |

| 33 | Okayama | 1996 | 3 |

| 34 | Hiroshima | 2627 | 1 |

| 35 | Yamaguchi | 761 | 0 |

| 36 | Tokushima | 134 | 1 |

| 37 | Kagawa | 735 | 0 |

| 38 | Ehime | 571 | 1 |

| 39 | Kochi | 680 | 1 |

| 40 | Fukuoka | 2875 | 9 |

| 41 | Saga | 360 | 0 |

| 42 | Nagasaki | 702 | 0 |

| 43 | Kumamoto | 1229 | 3 |

| 44 | Oita | 442 | 1 |

| 45 | Miyazaki | 841 | 1 |

| 46 | Kagoshima | 729 | 1 |

| 47 | Okinawa | 133 | 0 |

| Three most affected prefecturesa | 3937 | 732 | |

| Others | 58 287 | 271 | |

aThe three prefectures that were most severely affected by the earthquake include Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures.

DISCUSSION

The present survey is the first nationwide survey to investigate how the Great East Japan Earthquake affected preschool children’s physical development and health status. The main strength of the present survey is the large amount of data we acquired. With the cooperation of 3624 nursery schools all over Japan, we established nationwide retrospective cohorts of 53 747 children who were born from April 1, 2004, to April 2, 2005, and 69 004 children who were born from April 1, 2006, to April 2, 2007. These cohorts represent 4.9% and 6.3% of the number of births in Japan during the same period, respectively.19

Preschool education in Japan is mainly provided either by nursery schools, which are governed by the Child Welfare Act and operate under the supervision of municipal governments,16,20,21 or by kindergartens, which are governed by the School Education Act22; a nursery school is a childcare and educational facility that cares for children ranging from newborn infants to preschool children, whereas a kindergarten offers early childhood education for children aged 3 to 5 years. Because nursery schools care for children for a longer period than kindergartens, we targeted nursery school children and obtained longitudinal data of physical measurements. Generalizability should be interpreted with caution. However, it has been reported that more than 40% of Japanese preschool children aged 3 years and older currently attend nursery schools and that the number of nursery school children has been increasing,16,23 so nursery school children may be sufficiently representative.

In addition, all nursery school teachers have paid close attention to children’s physical development by conducting periodic body measurements. They graduated from schools designated by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare as educational institutions for nursery teachers, passed a national examination, and registered in the nursery teachers’ registry.21 Therefore, the anthropomorphic measurements obtained by such qualified teachers may be sufficiently reliable and accurate.

Ochi et al suggested that evaluations of the health impacts of disasters need baseline data from before the events.11 We therefore retrospectively collected nursery school children’s anthropometric measurements for a maximum of 14 times. Specifically, for children who experienced the disaster during their preschool days, we obtained their height and weight measured in April and October between 2006 and 2012, including 10 measurements before the disaster and four measurements after the disaster. Thus, the data reflect childhood physical development trajectories before and after the disaster.

We observed preschool children who had personal experiences with the disaster not only in Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima Prefectures, which were devastated by the disaster, but also in other areas all over Japan. Among 1003 children who were reported to have specific disaster experiences, 271 (27.0%) were residing outside of the affected prefectures. Because we conducted a nationwide survey, we collected valuable data, including data on children who might have moved from the affected areas.

In conclusion, by comprehensively examining the results from the present survey, we aim to provide valuable epidemiological evidence that may not only shed light on the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake disaster on preschool children’s physical development and health, but may also provide specific suggestions for response to the next mega-disaster worldwide.

ONLINE ONLY MATERIALS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The “Nationwide Nursery School Survey on Child Health throughout the Great East Japan Earthquake” was conducted as a part of the “Surveillance Study on Child Health in the Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster Area” and supported in full by the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant (H24-jisedai-shitei-007, fukkou).

The following are members of the working group for childhood physical development evaluation based on the grant above: Shigeo Kure (PI), Professor and Chairman, Department of Pediatrics, Tohoku University; Susumu Yokoya, Department of Medical Subspecialties, National Center for Child Health and Development; Toshiaki Tanaka, President, Japanese Association for Human Auxology; Noriko Kato, Research Managing Director, National Institute of Public Health; Tsuyoshi Isojima, Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, The University of Tokyo; Shoichi Chida, Professor and Chairman, Department of Pediatrics, Iwate Medical University; Mitsuaki Hosoya, Professor and Chairman, Department of Pediatrics, Fukushima Medical University; Atsushi Ono, Research Associate, Department of Pediatrics, Fukushima Medical University; Zentaro Yamagata, Professor, Department of Health Sciences, University of Yamanashi; Hiroshi Yokomichi, Assistant Professor, Department of Health Sciences, University of Yamanashi; Soichiro Tanaka, Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Tohoku University; Shinichi Kuriyama, Professor, International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS), Tohoku University; Masahiro Kikuya, Associate Professor, Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (ToMMo), Tohoku University; Mami Ishikuro, Assistant Professor, ToMMo, Tohoku University; Hiroko Matsubara, Postdoctoral Research Associate, IRIDeS, Tohoku University.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the nursery teachers who completed questionnaires, as well as to Dr. Ikuo Endo, President of the Japan Society for Well-being of Nursery-schoolers, for their support and cooperation.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Japan Meteorological Agency [Internet]. Tokyo: The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake -Portal- [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.jma.go.jp/jma/en/2011_Earthquake/2011_Earthquake.html.

- 2.Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. White paper on disaster management 2011 [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2014 Dec 24]. Available from: http://www.bousai.go.jp/kaigirep/hakusho/pdf/WPDM2011_Summary.pdf.

- 3.Ishigaki A, Higashi H, Sakamoto T, Shibahara S. The Great East-Japan Earthquake and devastating tsunami: an update and lessons from the past great earthquakes in Japan since 1923. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:287–99. 10.1620/tjem.229.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mimura N, Yasuhara K, Kawagoe S, Yokoki H, Kazama S. Damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami—a quick report. Mitig Adapt Strategies Glob Change. 2011;16:803–18. 10.1007/s11027-011-9297-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suppasri A, Koshimura S, Imai K, Mas E, Gokon H, Muhari A. Damage characteristic and field survey of the 2011 Great East Japan tsunami in Miyagi prefecture. Coast Eng J. 2012;54(1):1250005 10.1142/S0578563412500052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Police Agency. Damage situation and police countermeasures [internet]. 2014 [updated 2014 Sep 11; cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.npa.go.jp/archive/keibi/biki/index_e.htm.

- 7.Japan Atomic Energy Atomic Agency [Internet]. Tokyo: Situation and response of JAEA to the Great East Japan Earthquake [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://fukushima.jaea.go.jp/english/response/index.html.

- 8.Yamaguchi K; Radiation Survey Team of Fukushima University . Investigations on radioactive substances released from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2011;57(2):75–80. 10.5387/fms.57.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hosoda M, Tokonami S, Sorimachi A, Monzen S, Osanai M, Yamada M, et al. The time variation of dose rate artificially increased by the Fukushima nuclear crisis. Sci Rep. 2011;1:87. 10.1038/srep00087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCurry J. Fukushima residents still struggling 2 years after disaster. Lancet. 2013;381:791–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60611-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochi S, Murray V, Hodgson S. The Great East Japan Earthquake disaster: a compilation of published literature on health needs and relief activities, March 2011–September 2012. PLoS Curr [serial online]. 2013. [cited 2014 Dec 24]; ecurrents.dis.771beae7d8f41c31cd91e765678c005d. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3682758/. 10.1371/currents.dis.771beae7d8f41c31cd91e765678c005d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanno T, Iijima K, Abe Y, Koike T, Shimada N, Hoshi T, et al. Peptic ulcers after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami: possible existence of psychosocial stress ulcers in humans. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(4):483–90. 10.1007/s00535-012-0681-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa S, Ishiki M, Nako K, Okamura M, Senda M, Sakamoto T, et al. Effects of the Great East Japan Earthquake and huge tsunami on glycaemic control and blood pressure in patients with diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open [serial online]. 2012. Apr 13 [cited 2014 Dec 24];2(2):e000830. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/2/e000830.full. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiga H, Miyazawa T, Kinouchi Y, Takahashi S, Tominaga G, Takahashi H, et al. Life-event stress induced by the Great East Japan Earthquake was associated with relapse in ulcerative colitis but not Crohn’s disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open [serial online]. 2013. Feb 8 [cited 2014 Dec 24];3(2):e002294. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/2/e002294.full. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi S, Hanagama M, Yamanda S, Satoh H, Tokuda S, Kobayashi M, et al. Impact of a large-scale natural disaster on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the aftermath of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Respir Investig. 2013;51(1):17–23. 10.1016/j.resinv.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Internet]. Tokyo: Press Release: Report on nursery schools [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/2r9852000002khid-att/2r9852000002khju.pdf (in Japanese).

- 17.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [Internet]. Tokyo: Guidebook for starting school [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.mext.go.jp/component/english/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2011/03/17/1303764_008.pdf.

- 18.National Institute of Public Health [Internet]. Wako: Physical development assessment manual [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.niph.go.jp/soshiki/07shougai/hatsuiku/index.files/katsuyou_130805.pdf (in Japanese).

- 19.Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications [Internet]. Tokyo: Vital statistics [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/GL08020103.do?_toGL08020103_&listID=000001101883&requestSender=estat (in Japanese).

- 20.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Internet]. Tokyo: Guideline description for childcare in nursery schools [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kodomo/hoiku04/pdf/hoiku04b.pdf (in Japanese).

- 21.Child Welfare Act, No. 164 of December 12, 1947. Available from: http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail_main?vm=&id=11.

- 22.School Education Act, L. No. 26 of 1947. Available from: http://law.e-gov.go.jp/htmldata/S22/S22HO026.html (in Japanese).

- 23.Cabinet Secretariat [Internet]. Tokyo: The status of the implementation of preschool education and childcare [cited 2014 Oct 06]. Available from: http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/youji/dai2/sankou1.pdf (in Japanese).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.