Abstract

AIM: To reduce the incidence of postoperative anastomotic leak, stenosis, gastroesophageal reflux (GER) for patients with esophageal carcinoma, and to evaluate the conventional method of esophagectomy and esophagogastroplasty modified by a new three-layer-funnel-shaped (TLF) esophagogastric anastomotic suturing technique.

METHODS: From January 1997 to October 1999, patients with clinical stage I and II (IIa and IIb) esophageal carcinoma, which met the enrollment criteria, were surgically treated by the new method (Group A) and by conventional operation (Group B). All the patients were followed at least for 6 months. Postoperative outcomes and complications were recorded and compared with the conventional method in the same hospitals and with that reported previously by McLarty et al[7] in 1997 (Group C).

RESULTS: 58 cases with stage I and II (IIa and IIb) esophageal carcinoma, including 38 males and 20 females aged from 34 to 78 (mean age: 57), were surgically treated by the TLF anastomosis and 64 by conventional method in our hospitals from January 1997 to October 1999. The quality of swallowing was improved significantly (Wilcoxon W = 2142, P = 0.0001) 2 to 3 months after the new operation in Group A. Only one patient had a blind anastomatic fistula diagnosed by barium swallow test 2 months but healed up 3 weeks later. Postoperative complications occurred in 25 (43%) patients, anastomotic stenosis in 8 (14%), and GER in 13 (22%). The incidences of postoperative anastomotic leak, stenosis and GER were significantly decreased by the TLF anastomosis method compared with that of conventional methods (χ2 = 6.566, P = 0.038; χ2 = 10.214, P = 0.006; χ2 = 21.265, P = 0.000).

CONCLUSION: The new three-layer-funnel-shaped esophagogastric anastomosis (TLFEGA) has more advantages to reduce postoperative complications of anastomotic leak, stricture and GER.

INTRODUCTION

Surgical therapy is considered the major method for treatment of operable esophageal cancer[1-2]. Unfortunately, there are many operative complications after classical standard esophagectomy and esophageal reconstruction with stomach in patients with esophageal carcinoma. Anastomotic leak, with a rate of about 12%-14% as reported, is the most severe complication and the principal cause of death after operation[3-7]. Anastomotic stenosis and gastroesophageal reflux (GER), with higher rates of about 36.4%-40% and 50%-60% respectively, result in dysphagia, heartburn, regurgitation and nause[3-7].

We modified the conventional method of esophagectomy and created a new three-layer-funnel-shaped (TLF) esophagogastric anastomotic suturing technique, which significantly reduced postoperative complications of anastomotic leak, stricture and GER.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and preoperative examination

From January 1997 to October 1999, the patients with clinical stage I and II (IIa and IIb) esophageal carcinoma, which met the enrollment criteria, were allocated into two groups and surgically treated by a new method (Group A) and the conventional operation (Group B) in our hospitals. All patients were diagnosed by esophagoscopy and biopsy. Barium swallow test confirmed that the cancer length was < 5 cm, there was absence of sinus or fistula. No lung or liver metastases was detected by radiography and/or computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and ultrasonography of the upper abdomen. Supraclavicular lymph nodes were not involved by physical examination in all patients. Karnofsky performance status was > 70. All patients assessed by pulmonary functional test were fit for thoracotomy. Patients with stage III or IV esophageal carcinoma, inoperable conditions, receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy before or after operation were precluded.

Methods of operation

Partial or sub-total resection of esophagus was routinely performed through left or right thoracic incision, some cases need cervical incision, with removal of paraesophageal, subcarinal, supradiaphragmatic, perihiatal, as well as left gastric and coeliac lymph node group. Partial gastrectomy was performed with esophagogastric junction carcinoma. The stomach remained and was reconstructed as a tube-like pouch to replace the resected part of the esophagus. The anastomotic techniques were improved as follows:

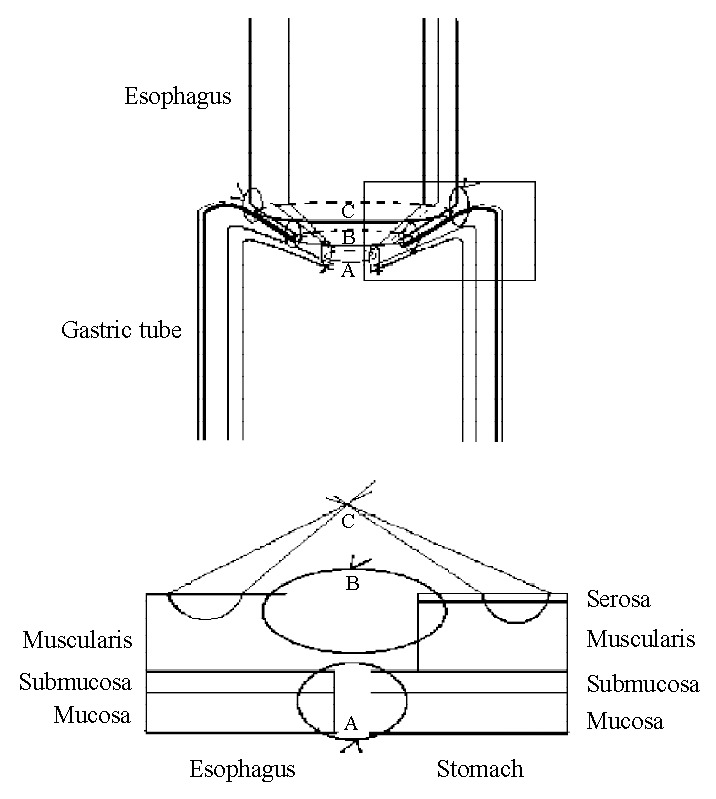

When the gastric tube was constructed, an adequate amount of greater omentum was reserved for protecting the right gastroepiploic vessels and the blood supply of the gastric tube. The gastric tube was kept long enough to avoid tension and pulled along the esophageal bed, anchored to the back of the chest wall beside the mediastinum (The cervical cancer need a cervical incision to perform the anastomotic suture in the neck). First, the esophageal muscular layer was cut 3.0-3.5 cm in length into the inclined cycle, and the esophageal mucosa was kept 1.0-1.5 cm longer. Between the short gastric vessel, the sero-muscular layer was incised 4.0-4.5 cm, and its posterior aspect was hand-sewn to the same aspect of esophageal muscular layer. Then, excised the inner circular muscle layer and mucosa of stomach for 2.5-3.0 cm long and anastomosed to the esophageal mucosa by interupted suture. The anterior aspect of the esophageal muscular and the gastric sero-muscular layer was sewn finally with fundoplication by inversion suture. The fundoplication suture cycle is 1.0-2.0 cm larger than the suture cycle of the esophageal muscular-to-sero-musculer layer of the stomach (Figure 1). The other procedures were performed as usual.

Figure 1.

Technique of three-layer-funnel-shaped(TLF) esophagogastric anastomosis. A: mucosa-to-mucosa suture cycle; B: the esophagus muscular to gastric sero-muscular suture cycle; C: fundoplication suture cycle.

Postoperative management and follow-up

After the operation, all patients were treated routinely by thoracic drainage, nutrition support, and antibiotics. The swallowing ability and symptoms of anastomotic leak, stricture and GER were observed clinically as reported[3-7]. All patients were evaluated clinically by their general condition, eating habits, swallowing ability and barium swallow test or esophagoscopy 2 to 3 months after the completion of all treatments and followed up at intervals of 2-3 months for at least 6 months.

Postoperative anastomotic leak was diagnosed clinically by leakage of gastrointestinal contents and radiographically extravasation of water-soluble contrast medium at the site of anastomosis. The anastomotic stricture was defined as any form of narrowing in the anastomosis region by contrast swallow study (≤ 2.0 cm in diameter in obverse and lateral posture) and any symptom of dysphagia when swallowing solid food, semisolids or liquids, requiring endoscopic dilation. GER was present if the patient had intermittent or continuous heartburn, regurgitation and nausea, especially that required antacids for relief of heartburn, or barium regurgitation at horizontal posture or Trendelenburg’s position on radiographic examination.

Statistical analysis

All patients’ general characteristics, pathological pattern of carcinoma, clinical staging, swallowing ability, postoperative complications, and incidences of anastomotic leak, stricture, and GER were recorded and compared to that treated by conventional methods in the same hospitals and that reported previously by McLarty et al[7]. Quantitative data were compared by using Independent-Samples t test and qualitative data by Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, and Wilcoxon rank test. Statistical significance was assumed at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

58 patients (Group A), including 38 males and 20 females aged from 34 to 78 (mean age: 57), 54 cases with dysphagia, 4 without any symptom by routine examination, were successfully treated by the new method and 64 (Group B) by the conventional operation. There were no severe intraoperative complications, no operative mortality, no abscesses or uncontrolled infections occurred in all patients. Treated by the new method, the quality of swallowing of the patients improved significantly (P = 0.0001) 2 to 3 months after the operation (Table 1). In Group A, only one patient had a minute blind anastomatic fistula into the immediate paraesophageal soft tissues without causing any symptoms which was diagnosed by barium swallowing test 2 months after the operation, but healed up automatically without any treatment 3 weeks afterwards. Postoperative complications occurred in 25 patients (43%), including incision and/or thoracic cavity bleeding in 2, wound infection in 1, pneumonia in 1, anastomotic stenosis in 8 (14%), and GER in 13 (22%). There were 7 of 8 cases with symptom of dysphagia but dilated successfully by endoscopy, 1 case with moderate stricture could only eat semisolid or liquid food 1 year after the operation.

Table 1.

Evaluation of swallowing quality after operation (Group A, n = 58)

| No symptom of dysphagia |

With symptom of dysphagia |

|||

| Solid Food | Semisolids | Liquids | ||

| Preoperation | 4 (6.9%) | 23 (39.7%) | 26 (44.8%) | 5 (8.6%) |

| Postoperation | 50 (86.2%) | 5 (8.6%) | 2 (3.4%) | 1 (1.7%) |

Analysed by wilcoxon rank test (Wilcoxon W = 2142, P = 0.0001), swallowing quality of patients after operation increased significantly compared with that before operation.

Except the difference of pathological type of carcinoma in the west from that in China, which was not the major factor that affected the operation modality and the early outcomes, the patients’ general characteristics, tumor site and clinical staging in Group A were analogous to those in Group B and that reported previously by Allison et al (Table 2). Although the total incidence of postoperative complications were not different due to different method of calculation, the incidences of anastomotic leak, stricture, and GER in our new method therapy group were significantly reduced compared with that of conventional therapy groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics and pathological condition of patients in different groups

| A New method (n = 58) | B Conventional (n = 64) | C Reporteda (n = 107) |

Statistical analysis |

||

| x2/t | P Value | ||||

| Sex (male/female) | 46/12 | 43/21 | 81/26 | 2.563 | 0.279 |

| Mean age (range) (years) | 57 (34-78) | 54(28-76) | 62 (30-81) | ||

| Tumor site | |||||

| Upper (include cervical) | 4 (7%) | 3 (4.6%) | 2 (2%) | 2.731 | 0.604 |

| Middle | 21 (36%) | 24 (37.5%) | 43 (40%) | ||

| Lower(junctional part) | 33 (57%) | 37 (57.8%) | 62 (58%) | ||

| Pathological typeb | |||||

| Squamous | 32 (55%) | 34(53%) | 28 (26%) | 14.399 | 0.001b |

| Adenocarcinoma | 22 (38%) | 28(44%) | 72 (67%) | 1.155 | 0.561c |

| Others | 4 (7%) | 2(3%) | 7 (7%) | ||

| Tumor Diameter | |||||

| (Mean ± SD)(cm) | 3.1 ± 1.94 | 3.6 ± 1.58 | ND | 1.551 (t) | 0.084 |

| Clinical Staging | |||||

| Stage I | 18 (31%) | 22 (35%) | 34 (32%) | 7.272 | 0.122 |

| StageIIA | 31 (53%) | 29 (45%) | 65 (61%) | ||

| StageIIB | 9 (16%) | 13 (22%) | 8 (8%) | ||

By McLarty AJ, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, et al[7]. Ann Thorac Surg, 1997; 63: 1568-1572.

The pathological type of esophageal carcinoma was different as reported in the west from that in China (P = 0.001), but it was not the major factor that affected the methods and early outcomes of operation.

Compared the pathologic type of cancer treated by the new(Group A) and the conventional (Group B) methods. ND: No data available.

Table 3.

Postoperative Outcomes and Complications of Patients in the above Groups

| A New method (n = 58) | B Conventional (n = 64) | C Reporteda (n = 107) |

Statistical analysis |

||

| x2/t | P Value | ||||

| No complication | 33 (56.9%) | 26 (40.6%) | 17 (16%) | 29.716 | 0.000 |

| Complications | 25 (43%) | 38 (59.3%) | 43 (40%) | 2.258 | 0.353 |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 (2%) | 4 (6%) | 13 (12%) | 6.566 | 0.038 |

| Anastomotic stricture | |||||

| Dysphagia to food | 8 (13%) | 24 (37.5%) | 40 (37%) | 10.214 | 0.006 |

| Postoperative dilation | 8 (14%) | 23 (35.9%) | 46 (43%) | 14.746 | 0.001 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | |||||

| Reflux Symptoms | 13 (22%) | 33 (52%) | 64 (60%) | 21.265 | 0.000 |

| Required antiacids | 11 (19%) | 20 (32%) | 31 (29%) | 2.026 | 0.363 |

By McLarty AJ, et al[7]. Ann Thorac Surg, 1997; 63: 1568-1572.

DISCUSSION

There are clear evidences that patients with earlier stage esophageal carcinoma have relatively good outcomes when treated with resection only, especially through thoracic incision which is easy to remove the regional lymph nodes and to carry out the whole operation[1,2,8]. Multimodality treatment with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy was recommended for esophageal carcinoma by some studies but the results are debatable recently by other studies due to poor outcomes at present[9-12]. Yet there are still many postoperative complications such as leaks, stricture, and GER, which affect the esophageal function and quality of life, as well as long-term survival of the patients[3-7].

Anastomotic leak is mainly caused by ischemia of the anastomosis and errors in surgical technique[7]. Except few recurrence of carcinoma which occurs usually above 6 months after operation, small-bore anastomosis and fibrotic stenosis are the principal causes of anastomotic stricture that results in poor function of swallowing[3,4,7]. Some studies show that there is a trend toward slightly higher leaking rate for one-layer anastomosis and a higher stricture rate for two-layer anastomosis[4,13,14]. As for GER, it is basically caused by loss or alteration of normal anatomical structure, location, and function of esophagus, cardia and stomach[3,5,6].

The new three-layer-funnel-shaped esophagogastric anastomotic suturing technique, we report here, has more advantages than the classical ones. First, it not only maintains adequate arterial perfusion and venous drainage by reserving enough amount of greater omentum, protecting the right gastroepiploic vessels, and avoiding excessive tension of gastric tube and esophagus, but also maintains accurate mucosa-to-mucosa, muscular-to-muscular apposition and enhances the anastomosis by three-layer sutures, as well as omentum or pleura covering. This significantly avoids the occurrence of anastomotic leak according to our clinical data.

Second, it forms three inclined suture cycles in different diameters at different levels (Figure 1). The fundoplication suture cycle and the esophageal muscular-to-gastric sero-musculer suture cycle are ellipse like and big enough to form a large-bore anastomosis that reduces stricture formation. That is why the incidence of anastomotic strictures being low and dilated easily and effectively in our study.

Third, with adequate mucosa-to-mucosa suture, the new method reconstructed a soft mucosa petal which forms the third suture cycle, smaller in diameter and easier to open or shrink automatically, and prevents GER effectively. Although postoperative GER still occurred in 22% which need further study, it was significantly decreased compared to the conventional method[15]. Twenty-four-hour esophageal pHmonitor is a new method to diagnose GER and we plan to carry out a further randomized clinical trial to more scientifically evaluate the anti-GER effects of the mucosa petal created by the new anastomosis[16].

Like all conventional anastomotic suture techniques, we also emphasize that it is important for the anastomotic healing to prevent infection, malnutrition, influence of chemotherapy and radiotherapy and other related factors in perioperative stage. To prevent the anastomotic tissue injury from strangulation, one should never suture too tightly, or place an excessive number of sutures. In addition, each suture ‘bite’ of esophageal muscular layer may be transversely sewn so as to overcome the problem because the longitudinally oriented esophageal muscle holds suture poorly.

Some studies recommend that the stapled esophagogastric anastomosis after resection for esophagogastric or cardia cancer is a simple and expeditious procedure, carrying an acceptable perioperative morbidity and cancer recurrence rate[17-19]. But except the technical problems caused by the staples, the stricture rate of stapled anastomosis was higher[17-21]. Beitler et al[22] systemically reviewed the related randomized controlled trials and pointed out that both stapled and hand-sewn techniques are acceptable but both need further improvement. GER is recently demonstrated as a main risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma and is the main factor that decreases the quality of life of patients after operation[7,23-30]. The new three-layer-funnel-shaped esophagogastric anastomotic suturing technique is a pilot study, its effect on anti-GER has not been very ideal, and we are making further efforts for improvement, especially that on the prevention of anastomotic leak, stricture and GER.

Footnotes

Edited by Wu XN

References

- 1.Simchuk EJ, Alderson D. Oesophageal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:760–765. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i6.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Law S, Fok M, Chow S, Chu KM, Wong J. Preoperative chemotherapy versus surgical therapy alone for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a prospective randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:210–217. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whooley BP, Law S, Alexandrou A, Murthy SC, Wong J. Critical appraisal of the significance of intrathoracic anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy for cancer. Am J Surg. 2001;181:198–203. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swisher SG, Hunt KK, Holmes EC, Zinner MJ, McFadden DW. Changes in the surgical management of esophageal cancer from 1970 to 1993. Am J Surg. 1995;169:609–614. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urschel JD. Esophagogastrostomy anastomotic leaks complicating esophagectomy: a review. Am J Surg. 1995;169:634–640. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruns CJ, Gawenda M, Wolfgarten B, Walter M. [Cervical anastomotic stenosis after gastric tube reconstruction in esophageal carcinoma. Evaluation of a patient sample 1989-1995] Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1997;382:145–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLarty AJ, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Pairolero PC, Harmsen WS. Esophageal resection for cancer of the esophagus: long-term function and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1568–1572. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller JD, Jain MK, de Gara CJ, Morgan D, Urschel JD. Effect of surgical experience on results of esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1997;65:20–21. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199705)65:1<20::aid-jso4>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, Kelly A, Keeling N, Hennessy TP. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosset JF, Gignoux M, Triboulet JP, Tiret E, Mantion G, Elias D, Lozach P, Ollier JC, Pavy JJ, Mercier M, et al. Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone in squamous-cell cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:161–167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707173370304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein HJ, Sendler A, Fink U, Siewert JR. Multidisciplinary approach to esophageal and gastric cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:659–682; discussions 683-686. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urba SG, Orringer MB, Turrisi A, Iannettoni M, Forastiere A, Strawderman M. Randomized trial of preoperative chemoradiation versus surgery alone in patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:305–313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zieren HU, Müller JM, Pichlmaier H. Prospective randomized study of one- or two-layer anastomosis following oesophageal resection and cervical oesophagogastrostomy. Br J Surg. 1993;80:608–611. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang SJ, Wen DG, Zhang J, Man X, Liu H. Intensify standardized therapy for esophageal and stomach cancer in tumor hospitals. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:80–82. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, Liu J, Zhao X, Lei J, Cong Q, Li W, Li B, Wang F, Cao F, Zhang X, et al. [Can esophagogastric anastomosis prevent gastroesophageal reflux] Zhonghua Waike Zazhi. 1999;37:71–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun M, Wang WL, Wang W, Wen DL, Zhang H, Han YK. Gastroesophageal manometry and 24-hour double pH monitoring in neonates with birth asphyxia. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:695–697. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisgaard T, Wøjdemann M, Larsen H, Heindorff H, Gustafsen J, Svendsen LB. Double-stapled esophagogastric anastomosis for resection of esophagogastric or cardia cancer: new application for an old technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9:335–339. doi: 10.1089/lap.1999.9.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh D, Maley RH, Santucci T, Macherey RS, Bartley S, Weyant RJ, Landreneau RJ. Experience and technique of stapled mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone CD, Heitmiller RF. As originally published in 1994: Simplified, standardized technique for cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. Updated in 2000. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:999–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01743-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valverde A, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Elhadad A. Manual versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after resection for carcinoma: a controlled trial. French Associations for Surgical Research. Surgery. 1996;120:476–483. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berrisford RG, Page RD, Donnelly RJ. Stapler design and strictures at the esophagogastric anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:142–146. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beitler AL, Urschel JD. Comparison of stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomoses. Am J Surg. 1998;175:337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaheen N, Ransohoff DF. Gastroesophageal reflux, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal cancer: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;287:1982–1986. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johanson JF. Critical review of the epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease with specific comparisons to asthma and breast cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:S19–S21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(01)02579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Serag HB, Hepworth EJ, Lee P, Sonnenberg A. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a risk factor for laryngeal and pharyngeal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2013–2018. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson MK, Durkin A. Long-term survival after esophagectomy for Barrett's adenocarcinoma in endoscopically surveyed and nonsurveyed patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:29–35; discussion 36. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye W, Chow WH, Lagergren J, Yin L, Nyrén O. Risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia in patients with gastroesophageal reflux diseases and after antireflux surgery. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1286–1293. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Incarbone R, Bonavina L, Saino G, Bona D, Peracchia A. Outcome of esophageal adenocarcinoma detected during endoscopic biopsy surveillance for Barrett's esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:263–266. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaheen N, Ransohoff DF. Gastroesophageal reflux, barrett esophagus, and esophageal cancer: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:1972–1981. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]