Abstract

Background and Purpose

Allosteric modulation of the mGlu2 receptor is a potential strategy for treatment of various neurological and psychiatric disorders. Here, we describe the in vitro characterization of the mGlu2 positive allosteric modulator (PAM) JNJ‐46281222 and its radiolabelled counterpart [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222. Using this novel tool, we also describe the allosteric effect of orthosteric glutamate binding and the presence of a bound G protein on PAM binding and use computational approaches to further investigate the binding mode.

Experimental Approach

We have used radioligand binding studies, functional assays, site‐directed mutagenesis, homology modelling and molecular dynamics to study the binding of JNJ‐46281222.

Key Results

JNJ‐46281222 is an mGlu2‐selective, highly potent PAM with nanomolar affinity (K D = 1.7 nM). Binding of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 was increased by the presence of glutamate and greatly reduced by the presence of GTP, indicating the preference for a G protein bound state of the receptor for PAM binding. Its allosteric binding site was visualized and analysed by a computational docking and molecular dynamics study. The simulations revealed amino acid movements in regions expected to be important for activation. The binding mode was supported by [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding experiments on mutant receptors.

Conclusion and Implications

Our results obtained with JNJ‐46281222 in unlabelled and tritiated form further contribute to our understanding of mGlu2 allosteric modulation. The computational simulations and mutagenesis provide a plausible binding mode with indications of how the ligand permits allosteric activation. This study is therefore of interest for mGlu2 and class C receptor drug discovery.

Abbreviations

- JNJ‐46281222

3‐(Cyclopropylmethyl)‐7‐[(4‐phenyl‐1‐piperidinyl)methyl]‐8‐(trifluoromethyl)‐1,2,4‐triazolo[4,3‐a]pyridine

- NAM

negative allosteric modulator

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- VFT

Venus Flytrap domain

Tables of Links

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (Alexander et al., 2013).

Introduction

The metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors modulate cell excitability and synaptic transmission when activated by endogenous glutamate. They belong to the glutamate‐like subfamily (class C) of GPCRs and are divided into three subgroups, group I (mGlu1, 5), group II (mGlu2, 3) and group III (mGlu4, 6‐8), based on their sequence homology, second messenger coupling and pharmacology (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Alexander et al., 2013).

Structurally, class C GPCRs are characterized by a large extracellular orthosteric binding domain, the so‐called Venus Flytrap domain (VFT), which is connected to the seven transmembrane (7TM) domain by a cysteine‐rich domain (CRD; Muto et al., 2007; Niswender and Conn, 2010). They are obligatory dimers and mainly exist as homodimers linked by a disulfide bond in the VFT (Romano et al., 1996; Kniazeff et al., 2011).

Activation of the mGlu2 receptor is a potential strategy for the treatment of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety and depression (Nicoletti et al., 2011). Interestingly, mGlu2 receptor activation can be enhanced by positive allosteric modulators (PAMs), which have little or no intrinsic efficacy and enlarge the effect exerted by endogenously released glutamate (Conn et al., 2009). The orthosteric binding site is highly conserved between mGlu receptors, and it is thus hard to develop selective orthosteric ligands. Next to that, allosteric ligands are more capable of crossing the blood brain barrier as they are less polar, due to their binding in the more hydrophobic 7TM domain (Gregory et al., 2011). For these reasons, the number of PAMs described has increased tremendously over the last decade (Trabanco and Cid, 2013). These include compounds such as LY487379 (Johnson et al., 2003), BINA (Galici et al., 2006), THIIC (also known as LY2607540, Fell et al., 2011) and JNJ‐40068782 (Lavreysen et al., 2013), which have been extensively characterized both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, two mGlu2 PAMs have reached clinical trials so far. Development of AZD8529 (described in patent WO2008150233, Ball et al., 2012) from AstraZeneca was discontinued after a phase 2a study in schizophrenic patients due to a lack of efficacy (Cook et al., 2014). JNJ‐40411813 (also known as ADX71149) from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Addex Therapeutics failed to meet the criterion for efficacy signal in patients with major depressive disorder with significant anxiety symptoms. In contrast, in an exploratory phase 2a study in schizophrenia, not powered to determine statistical significance of effects rather a signal generation study, JNJ‐40411813 met the primary objectives of safety and tolerability and also demonstrated an effect in patients with residual negative symptoms (Cid et al., 2014).

The mGlu2 allosteric binding pocket has been elucidated by mutagenesis studies, which revealed an overlap between PAM and negative allosteric modulator (NAM) binding sites (Schaffhauser et al., 2003; Hemstapat et al., 2007; Rowe et al., 2008; Lundström et al., 2011; Farinha et al., 2015). The recent crystallization of the first class C GPCRs mGlu1 and mGlu5 7TM in complex with NAM molecules enables accurate mGlu homology modelling (Doré et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2014).

Here, the in vitro properties of JNJ‐46281222 are described, and we characterized [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 as a high‐affinity mGlu2 PAM. Its binding was studied in order to gain a better understanding of the relationship between orthosteric and allosteric binding sites at the mGlu2 receptor. In addition, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations based on an active state 7TM mGlu2 receptor model were performed to analyse the binding mode of JNJ‐46281222, which was validated experimentally in subsequent mutagenesis experiments. Altogether, this work offers new insights into the functioning of the mGlu2 receptor, which might contribute to the development of new and improved PAMs.

Methods

For additional methods, see Supporting Information.

Cell culture

CHO‐K1 cells stably expressing the wildtype (WT) hmGlu2 receptor (CHO‐K1_hmGlu2) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v v‐1) fetal calf serum, 88 IU·mL−1 penicillin, 88 μg·mL−1 streptomycin, 30.5 μg·mL−1 l‐proline and 400 μg·mL−1 G418 at 37°C and 5% CO2. CHO‐K1 cells were cultured in the same medium without G418. Cells were subcultured at a ratio of 1:10 twice every week.

Transient transfection

Transient transfections were performed as previously described (Farinha et al., 2015).

Radioligand binding assays

[3 H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding

After being thawed, membranes (Supporting Information) were homogenized using an Ultra Turrax homogenizer at 24 000 r.p.m. Samples were diluted in ice‐cold assay buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl pH 7.4, 2 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM MgCl2) to a total reaction volume of 100 μL and incubated at 15°C. Non‐specific binding was determined using 10 μM JNJ‐40068782; DMSO concentrations were ≤0.25%.

For saturation experiments, CHO‐K1_hmGlu2 membrane aliquots, containing 30 μg protein, and nine increasing concentrations of radioligand, ranging from 0.4 to 20 nM, were incubated for 60 min to allow equilibrium to be reached for all concentrations of radioligand. Non‐specific binding was determined at three concentrations of radioligand.

Association experiments were carried out by incubation of 6 nM of radioligand and membrane aliquots, containing 20 or 30 μg of protein for assays in the presence or absence of 1 mM glutamate respectively. The amount of receptor‐bound radioligand was determined at different time points up to 180 min.

Dissociation experiments were performed by a 60 min pre‐incubation of 6 nM radioligand and membrane aliquots containing 30 μg of protein or for assays in the presence of 1 mM glutamate or GTP, 20 or 50 μg respectively. Dissociation was initiated by addition of 10 μM JNJ‐40068782 (final concentration) in 5 μL, and the amount of remaining receptor‐bound radioligand was determined at different time points up to 120 min.

Displacement experiments were performed using 6 nM of radioligand and 10 concentrations of competing ligand, diluted by an HP D300 digital dispenser (Tecan, Giessen, The Netherlands) and incubated for 60 min. Membrane protein aliquots containing 30 or 40 μg were used for membranes stably expressing the hmGlu2 receptor or for transiently transfected hmGlu2 receptor constructs respectively.

For all assays, incubation was terminated by rapid filtration over GF/C filters through a Brandel harvester 24 (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) or over GF/C filterplates (PerkinElmer, Groningen, The Netherlands) on a PerkinElmer filtermate harvester. Filters were subsequently washed at least three times using ice‐cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris‐HCl pH 7.4). Filter‐bound radioactivity was determined using liquid scintillation spectrometry on a TRI‐Carb 2810 TR counter (PerkinElmer) or a P‐E 1450 Microbeta Wallac Trilux scintillation counter (PerkinElmer). [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 did not bind to CHO‐K1 membranes without hmGlu2 receptor expression (data not shown). For all radioligand binding experiments, radioligand concentrations were chosen such that <10% of the amount added was receptor‐bound.

[3 H]‐LY341495 binding

For saturation experiments, various concentrations of [3H]‐LY341495 from 0.5 to 30 nM were incubated with 10 μg membrane protein from the same batch of membranes as used for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 saturation binding experiments at 15°C for 60 min in a total volume of 100 μL. Non‐specific binding was determined at three concentrations of radioligand in the presence of 1 mM glutamate. Incubations were terminated, and samples were obtained and analysed as described under ‘[3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding’.

[3 H]‐DCG‐IV binding

For saturation experiments, unlabelled DCG‐IV was spiked with 20% [3H]‐DCG‐IV, resulting in final concentrations from 50 to 1500 nM. DCG‐IV was incubated with 75 μg membrane protein from the same batch of membranes as used for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 saturation binding experiments at 15°C for 60 min in a total volume of 100 μL. Non‐specific binding was determined at three concentrations of radioligand in the presence of 10 μM LY341495. Incubations were terminated, and samples were obtained and analysed as described under ‘[3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding’.

[35 S]‐GTPγS binding

[35S]‐GTPγS binding experiments were performed as previously described (Lavreysen et al., 2013).

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using Prism 5.00 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA). K D and B max were determined by a saturation binding analysis, using the equation Y = B max × K D/(K D + X). pIC50 values were obtained using non‐linear regression curve fitting into a sigmoidal concentration–response curve using the equation: Y = Bottom + (Top‐Bottom)/(1 + 10^(X‐LogIC50)). pKi values were obtained from pIC50 values using the Cheng–Prusoff equation (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973). Dissociation rate constants k off were determined by using an exponential decay analysis of radioligand binding. Association rate constants k on were determined using the equation k on = (k obs − k off)/[L], in which L is the concentration of radioligand used for association experiments and k obs is determined using exponential association analysis. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments performed in duplicate, unless stated otherwise. Statistical analysis was performed if indicated, using Student's two‐tailed unpaired t‐test or one‐way anova with Dunnett's post test. Observed differences were considered statistically significant if P‐values were below 0.05.

Building an mGlu2 receptor homology model

An active state model of the 7TM domain of human mGlu2 receptor (Uniprot code Q14416) bound to G protein was built using a combination of structural templates. The crystal structure of the human mGlu5 (PDB 4OO9, Doré et al., 2014) was used to model all 7TM helices except TM6. Extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) is not refined in the mGlu5 X‐ray structure; therefore, this important loop was modelled based on the mGlu1 receptor crystal structure (PDB 4OR2, Wu et al., 2014). Finally, the active structure of the β2‐adrenoceptor (PDB ID 3SN6, Rasmussen et al., 2011) was used to model both TM6 in its distinct open conformation and the corresponding G protein. For sequence alignment, see Supporting Information Fig. S1. This monomer 7TM has been shown experimentally to be activated upon PAM binding (El Moustaine et al., 2012). The sequence identity between mGlu2 and mGlu5 7TMs was 51%. The initial model was constructed in MOE v2014.9 (Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada), and then Maestro (Schrodinger LLC, New York, NY, USA) was used for structure preparation. The protein preparation tool was used to fix any missing side chains/atoms, PROPKA assigned protonation states, the hydrogen bonding network was optimized and brief minimization to RMSD (root‐mean‐square deviation) 0.5 Å was applied to remove any structural clashes. Amino acid numbering is based on recent recommendations (Isberg et al., 2015).

Docking of JNJ‐46281222

The ligand was prepared for docking using Maestro. Its basic pKa value was measured experimentally as 6.6. The structure‐activity relationship of molecules from this series does not require a charged centre for mGlu2 PAM activity (Cid et al., 2012). Hence, JNJ‐46281222 was modelled in an unionized state. Conformational sampling was performed with ConfGen, and multiple conformers were docked into the mGlu2 active state model using Glide XP. The docking grid was centred on the ligand position in the mGlu1 receptor structure. Sampling was increased in the Glide docking by turning on expanded sampling and passing 100 initial poses to post‐docking minimization. All other docking parameters were set to the defaults.

Molecular dynamics simulations

MD simulations were performed with GROMACS v4.6.5 (Hess et al., 2008). Ligand‐receptor complexes were embedded in a pre‐equilibrated box (10 × 10 × 19 nm) containing a lipid bilayer (297 POPC molecules) with explicit solvent (~47 000 waters) and 0.15 M concentration of Na+ and Cl− (~490 ions). The total size of the system was 174 000 atoms. Each system was energy minimized and subjected to a five‐step MD equilibration of 10, 5, 2, 2 and 2 ns respectively. In the first step, the whole system was fixed except for the hydrogens. In the second, the protein loops were released from restraints. In the final three steps, the restraints on the ligand and proteins were relaxed from 100, 50 and 10 kJ·mol−1·nm−2 respectively. Production simulations were performed for time periods between 200 and 500 ns without restraints using a 2 fs time step. A constant temperature of 300 K using separate v‐rescale thermostats for protein‐ligand, lipids and water plus ions was used. The LINCS algorithm was applied to freeze bond lengths. Lennard‐Jones interactions were computed using a 10 Å cut‐off, and the electrostatic interactions were treated using PME also with a 10 Å cut‐off. The AMBER99SD‐ILDN force field (Lindorff‐Larsen et al., 2010) was used for the protein, the parameters described by Berger et al. (1997 for lipids and the general Amber force field and HF/6‐31G*‐derived RESP atomic charges for the ligand. This combination of protein and lipid parameters has recently been validated (Cordomí et al., 2012).

Chemicals and reagents

BINA, THIIC (also known as LY2607540), RO4491533 (Woltering et al., 2010), AZD8529, JNJ‐40068782, JNJ‐46281222 (Figure 1; Cid‐Nuñez et al., 2010) and [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 were synthesized at Janssen Research and Development. DCG‐IV was purchased at R&D Systems Europe (Abingdon, UK). [3H]‐DCG‐IV and [3H]‐LY341495 were obtained from American Radiolabeled Companies (St. Louis, MO, USA). GTP and glutamate were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). CHO cells (CHO‐K1, ATCC: CCL‐61) were from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA). Other chemicals were from standard commercial sources.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of JNJ‐46281222. The position of the tritium label in [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 is denoted by *.

Results

Characterization of [3 H]‐JNJ‐46281222

Firstly, the affinity of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 for the mGlu2 receptor was determined by performing saturation binding experiments on membranes of CHO‐K1 cells stably expressing the hmGlu2 receptor (Figure 2). Receptor binding was saturable and defined by a K D of 1.7 nM with a B max of 1.1 pmol·mg−1 protein. Homologous displacement experiments with [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 resulted in a pKi value of 8.33 for JNJ‐46281222. In addition, a series of reference PAMs and a NAM based on various chemical scaffolds fully displaced [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding, resulting in pKi values ranging from 6.43 to 8.09 (Table 1), while pseudo‐Hill coefficients were all close to unity. Secondly, kinetic association and dissociation experiments were performed to determine the association (k on) and dissociation (k off) rate constants (Figure 2; Table 2). Equilibrium binding of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 was reached within 30 min as assessed by kinetic association experiments and best fit with a one‐phase model, whereas the dissociation curve was best fit with a two‐phase model. This resulted in a k obs value of 0.24 min−1 describing the association and two values describing the dissociation, that is, a k off,1 value of 0.040 min−1 and a k off,2 value of 0.77 min−1.

Figure 2.

Characterization of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to mGlu2 receptors stably expressed at CHO‐K1 membranes. (A) Saturation analysis of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding. A representative experiment is shown with similar data being obtained in two additional experiments. (B) Association and dissociation kinetics of 6 nM [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 at the mGlu2 receptor at 15°C. Association data were best fitted using a one‐phase exponential association model, whereas data for dissociation curves were best fitted using a two‐phase exponential decay model. Data are expressed as percentage of specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding and are shown as mean ± SEM of at least four individual experiments. Where bars are not shown, SEM values are within the symbol.

Table 1.

Receptor affinity of mGlu2 allosteric modulators determined by [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 displacement experiments

| Compound | pKi |

|---|---|

| JNJ‐46281222 | 8.33 ± 0.14 |

| JNJ‐40068782 | 7.58 ± 0.08 |

| BINA | 7.22 ± 0.15 |

| THIIC | 7.10 ± 0.04 |

| AZD8529 | 6.43 ± 0.03 |

| RO4491533 | 8.09 ± 0.09 |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments performed in duplicate.

Table 2.

Kinetic binding parameters for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to human mGlu2 receptors in the absence or presence of 1 mM glutamate

| k obs (min−1) | k on (nM‐1·min−1) a | k off (min−1) b | K D (nM) c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k off,1 | k off,2 | ||||

| [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 | 0.24 ± 0.019 | — | 0.040 ± 0.0061 | 0.77 ± 0.18 | — |

| [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222+1 mM glutamate | 0.19 ± 0.031 | 0.019 ± 0.0051 | 0.070 ± 0.0056 | — | 3.6 ± 0.99 |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments performed in duplicate.

a k on was determined using the formula k on = (k obs − k off)/[L].

bAll parameters were determined by computer analysis using a one‐phase model, except for dissociation of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 in the absence of glutamate, which was best described by a two‐phase model.

c K D was determined as the ratio k off/k on.

The effect of glutamate on [3 H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to the mGlu 2 receptor

Increasing concentrations of glutamate enhanced [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding by more than twofold (Figure 3; Table 3) with a modulatory potency (pEC50) for glutamate of 5.27. [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 displacement assays in the absence or presence of glutamate were performed with JNJ‐46281222 and JNJ‐40068782, which did not result in a significant change in affinity for both compounds (Figure 3; Table 4).

Figure 3.

The effects of glutamate and GTP on [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding. (A) Increasing concentrations of glutamate enhance the specific binding of 6 nM [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 to mGlu2 receptors expressed at CHO‐K1 cell membranes, whereas GTP inhibits specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding. (B) Effects of glutamate and GTP on homologous displacement of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 from mGlu2 receptors expressed at CHO‐K1 membranes. Data are normalized to specific binding in the absence of glutamate or GTP (set at 100%). (C, D) The effect of glutamate on mGlu2 receptor association and dissociation of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222. Data are expressed as specific binding of the respective curve, association plateaus are fixed at 100% specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding and dissociation plateau is fixed at 0% specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding. (E) Specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding after 9 min of dissociation in the absence or presence of GTP. *P <0.05 versus control, determined using Student's two‐tailed unpaired t‐test. All graphs are shown as mean ± SEM of three to six individual experiments performed in duplicate. Where bars are not shown, SEM values are within the symbol.

Table 3.

Pharmacological characterization of the effects of glutamate or GTP on specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to mGlu2 receptors

| pEC50/pIC50 | E max (%) a | Hill slope | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | 5.27 ± 0.08 | 125 ± 9.0 | 0.49 ± 0.04 |

| GTP | 5.95 ± 0.21 | −65 ± 8.0 | −0.58 ± 0.03 |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of three individual experiments performed in duplicate.

E max was determined as difference in total specific binding compared with binding in the absence of glutamate or GTP (set at 100%).

Table 4.

Displacement of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 by mGlu2 PAMs JNJ‐46281222 and JNJ‐40068782 from human mGlu2 receptors in the absence (control) or presence of 1 mM glutamate or GTP

| pIC50 | E max (%) a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | +1 mM Glu | +1 mM GTP | +1 mM Glu | +1 mM GTP | |

| JNJ‐46281222 | 7.71 ± 0.17 | 7.63 ± 0.14 | 7.00 ± 0.16 * | 150 ± 24 | −71 ± 4.4 |

| JNJ‐40068782 | 6.89 ± 0.06 | 7.15 ± 0.10 | 6.85 ± 0.06 | 127 ± 20 | −77 ± 4.5 |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments performed in duplicate.

E max was determined as difference in total specific binding compared with binding in the absence of glutamate or GTP (set at 100%).

P <0.05 compared with pIC50 control, determined using one‐way anova with Dunnett's post test.

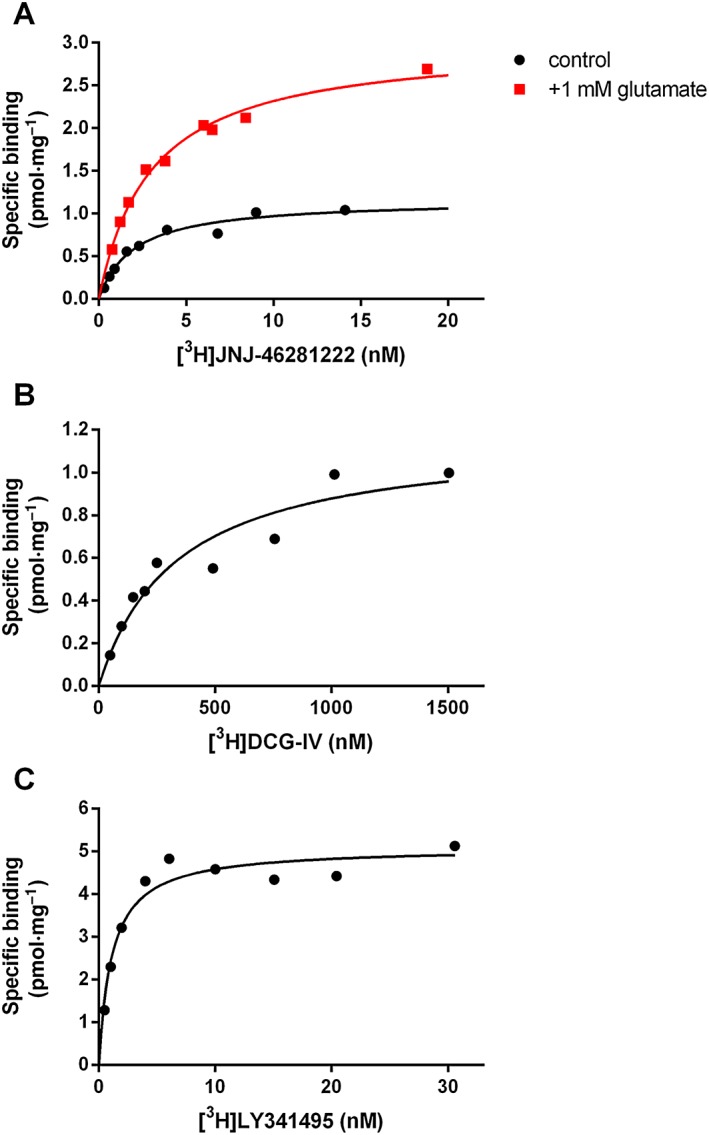

In addition, saturation binding of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 in the absence or presence of glutamate was performed (Figure 4), showing that the number of mGlu2 PAM binding sites (B max) was increased more than twofold in the presence of 1 mM glutamate, whereas the affinity (K D) was not significantly affected (Table 5).

Figure 4.

Saturation binding of radioligands to mGlu2 receptors expressed at CHO‐K1 membranes. (A) Saturation binding of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 to the mGlu2 allosteric binding site in the absence or presence of glutamate. (B) Saturation binding of [3H]‐DCG‐IV to the mGlu2 orthosteric binding site, determined by ‘spiked’ saturation (see text). (C) Saturation binding of [3H]‐LY341495 to the orthosteric binding site. Graphs shown are from a representative experiment performed in duplicate in each case.

Table 5.

Characteristics of saturation binding of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 in the absence or presence of glutamate and the orthosteric radioligands [3H]‐DCG‐IV and [3H]‐LY341495

| Radioligand | K D (nM) | B max (pmol·mg−1 protein) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 | 1.7 ± 0.17 | 1.1 ± 0.12 | |

| +1 mM glutamate | 2.5 ± 0.26 | 2.7 ± 0.25 | |

| [3H]‐DCG‐IV | 330/400 | 1.1/1.2 | |

| [3H]‐LY341495 | 2.4 ± 0.71 | 5.1 ± 0.39 |

Data for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 and [3H]‐LY341495 are shown as mean ± SEM of at least three individual experiments performed in duplicate. The same parameters measured for [3H]‐DCG‐IV are from two independent experiments (values of both experiments are given).

Next, the effect of glutamate on the kinetic association and dissociation rates of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 was examined. Glutamate decreased both rate constants to a small non‐significant extent (Figure 3; Table 2). Moreover, whereas dissocation in the absence of glutamate was best described using a two‐phase model, dissociation in the presence of 1 mM glutamate was best described with a one‐phase model, with a k off value of 0.070 min‐1. This presence of glutamate enabled further determination of the association rate constant k on, which was 0.019 nM−1·min−1. Based on these kinetic parameters, the kinetic K D was determined according to the equation K D = k off/k on, resulting in a K D value of 3.6 nM for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 in the presence of glutamate (Table 2), which was in good agreement with the K D value obtained from saturation experiments.

The effect of GTP on [3 H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to the mGlu 2 receptor

Radioligand displacement assays in the presence of increasing GTP concentrations were performed to evaluate the importance of the presence of a bound G protein for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding. As depicted in Figure 3, GTP inhibits [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding by 65% with a pIC50 value of 5.95. The affinity of JNJ‐46281222 was significantly decreased in the presence of 1 mM GTP, whereas this was not the case for JNJ‐40068782 (Table 4). Subsequently, the effect of 1 mM GTP on the dissociation rate of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 was examined. Because it was impossible to obtain reliable full curves with the vastly decreased [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 window under these conditions, [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 dissociation in the presence of 1 mM GTP was only determined at a single time point (i.e. after 9 min) and compared with the extent of dissocation in the absence of GTP at that same time point (Figure 3). In the presence of 1 mM GTP, the relative amount of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 still bound to the receptor after 9 min was significantly lower than in its absence, indicating an increased dissociation rate.

Saturation binding of orthosteric radioligands to the mGlu2 receptor

For comparison of the number of accessible orthosteric and allosteric binding sites, saturation experiments were performed using the orthosteric radioligands [3H]‐DCG‐IV and [3H]‐LY341495 (Figure 4; Table 5). The mGlu2 agonist [3H]‐DCG‐IV had a low affinity of 365 nM and a B max value of 1.2 pmol·mg−1 that corresponded to the B max value of 1.1 pmol·mg−1 obtained for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222. The high‐affinity antagonist [3H]‐LY341495 had a K D value of 2.4 nM and a B max value of 5.1 pmol·mg−1, approximately fivefold higher than for the PAM and for the agonist.

Quantification of potency of JNJ‐46281222 at the mGlu2 receptor

Figure 5 shows data from a representative determination of the concentration–effect curve of the glutamate‐induced binding of [35S]‐GTPγS in the absence and presence of various concentrations of JNJ‐46281222; similar data were obtained in a second experiment. A 100 nM concentration of JNJ‐46281222 enhanced the maximum glutamate‐induced [35S]‐GTPγS binding, that is, glutamate's efficacy, by approximately twofold, shifting the curve upward, and increased the glutamate potency fivefold, shifting the curve leftward. The potency of JNJ‐46281222 was determined by quantifying the increase in response to a fixed EC20 glutamate concentration (4 μM), as depicted in Figure 5. A pEC50 of 7.71 ± 0.02 was calculated, while the maximal response, 193 ± 5%, was almost twofold higher compared with the maximal glutamate response induced by 1 mM glutamate alone. In the absence of glutamate, JNJ‐46281222 shows a submaximal receptor activation of 42 ± 3% with a 10‐fold lower pEC50 value of 6.75 ± 0.08.

Figure 5.

Characterization of potency of JNJ‐46281222. (A) Stimulation of [35S]‐GTPγS binding to mGlu2 receptors induced by increasing concentrations of JNJ‐46281222. A representative experiment is shown, with similar data obtained in a second experiment. (B) Dose–response curve of JNJ‐46281222 in the presence of glutamate (EC20, 4 μM) on the binding of [35S]‐GTPγS. Data are expressed as the percentage of maximal response induced by 1 mM glutamate and are shown as mean ± SEM of 13 individual experiments performed in triplicate. Where bars are not shown, SEM values are within the symbol.

Docking of JNJ‐46281222 into the mGlu 2 7TM model

JNJ‐46281222 was docked into the active state mGlu2 homology model (Figure 6). The most energetically favourable binding pose is shown. The triazopyridine scaffold and lipophilic side chain substituent interact with the hydrophobic cluster formed between amino acids L6393 .32a.36c, F6433 .36a.40c, L7325 .43a.44c, W7736 .48a.50c and F7766 .51a.53c. The cyclopropylmethyl substituent goes deepest into the receptor and interacts closely with F7766 .51a.53c. The hydrophobic residues cluster tightly around the triazopyridine scaffold with L6393 .32a.36c and F6433 .36a.40c interacting on one face of the scaffold and L7325 .43a.44c and W7736 .48a.50c on the other. Amino acid N7355 .47a.47c acts as an H‐bond donor to the nitrogen acceptor (2.0 Å) in the triazo ring of the scaffold. The side chain of tryptophan W7736 .48a.50c, which is conserved in the mGlu receptors, points into the membrane in the same orientation as in the mGlu5 inactive state 7TM crystal structure. The cyclopropyl group makes a steric interaction at 2.3 Å distance. The CF3 group of the scaffold enters between TM3 and TM5 above N7355 .47a.47c and interacts with S7315 .42a.43c. The 4‐phenylpiperidine substituent is directed towards the extracellular side of the binding site, and the distal phenyl sits between F6232 .61a.56c and H723ECL2. The predicted binding mode overlaps with the allosteric site in mGlu1, whereas the mGlu5 modulator goes deeper into the receptor (Fig. S2).

Figure 6.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the binding of JNJ‐46281222 to the mGlu2 receptor. (A) The complete system used for MD simulations, including mGlu2 receptor 7TM monomer, G protein, ligand (JNJ‐46281222, magenta), lipids and solvent. (B) Close up of 7TM binding site showing interaction with a subset of important amino acids. MD starting position for ligand is coloured magenta; snapshot after 200 ns is turquoise. Movement of W7736.48a.50c from outwards orientation (magenta) at start of simulation to inwards orientation (turquoise) is highlighted. (C) RMSD of mGlu2 receptor monomer during the simulation.

The location of the allosteric binding pocket of JNJ‐46281222 at the mGlu 2 receptor

In order to validate the suggested location of the JNJ‐46281222 binding site, radioligand binding assays were performed on transiently transfected mGlu2 WT and mutant receptors. For the latter, mutations F643A3.36a.40c and N735D5.47a.47c were selected, because molecular docking studies indicated that these amino acids (amongst others) had important interactions with JNJ‐46281222. Receptor expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 7). [3H]JNJ‐46281222 binding to the selected mGlu2 receptor mutants was significantly decreased by approximately 10‐fold compared with WT, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

(A) Radioligand binding to mGlu2 receptor mutants F6433.36a.40c and N7355.47a.47c. Specific [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to WT or mutant mGlu2 receptors, transiently transfected in CHO‐K1 cells. Data were normalized to % specific binding compared with binding to WT mGlu2 receptors and are expressed as mean ± SEM of three individual experiments performed in duplicate. (B) Representative immunoblot of WT (left panel) and mutant mGlu2 receptors (middle, F643, and right, N735, panel) and actin. *P‐value <0.05 compared with WT, analysis was carried out using unnormalized data and determined using one‐way repeated‐measures ANOVA with Dunnett's post test.

Molecular dynamics simulations of JNJ‐46281222 and mGlu 2 7TM model

MD simulations of JNJ‐46281222 docked in the WT active state mGlu2 receptor model together with the G protein were performed for 500 ns. The overall structure was stable throughout the simulation with little fluctuation in RMSD deviation of the 7TM (Figure 6). The G protein also showed little structural fluctuation and remained bound to the intracellular side of the receptor keeping TM6 in an open conformation. The ligand maintained key interactions with amino acids such as L6393 .32a.36c, F6433 .36a.40c and N7355 .47a.47c (Figure 6). Amino acids in the vicinity of JNJ‐46281222 moved and adopted alternative orientations, which remained stable throughout the rest of the simulation. For instance, W7736 .48a.50c made a large rotational movement inwards after 20 ns, which was permitted by adjustment of the cyclopropylmethyl away from TM5 and towards F6433 .36a.40c. The tryptophan W7736 .48a.50c then rotated into the 7TM binding site to maintain interaction with the ligand whilst forming a new H‐bond interaction via its indole NH donor to the phenolic oxygen of Y6473 .39a.43c. Three additional replica simulations were performed for 200 ns using the same input but different starting velocities. Two of these showed consistent behaviour of W7736 .48a.50c. Additional MD simulations performed on the same system but without ligand did not display the inward rotation of W7736 .48a.50c. Likewise, the side chain remained outwards during a separate simulation with ligand but without G protein; see Supporting Information. Regarding the distal tail of JNJ‐46281222, the phenyl moiety moved deeper into the 7TM binding site during the 500 ns simulation and continued to interact with F6232 .61a.56c but no longer had contacts with H723 (mutation of which had previously shown no effect on JNJ‐46281222 functional activity (Farinha et al., 2015). Simulations performed on F643A3.36a.40c and N735D5.47a.47c mutant receptors were also stable with respect to the overall 7TM (Supporting Information). However, for the N735D5.47a.47c mutant, the ligand made a significant departure from its starting orientation. In summary, the MD simulations revealed the predicted binding mode to be stable and consistent with amino acids making key interactions.

Discussion

We demonstrated that JNJ‐46281222 is a high‐affinity mGlu2 PAM (K D = 1.7 nM) with a high modulatory potency (pEC50 = 7.71 ± 0.02) on the effect of the endogenous agonist glutamate in a [35S]‐GTPγS binding assay, where it increased glutamate's maximum effect by approximately twofold to its ‘ceiling’ allosteric effect (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002). These data are in line with previously reported affinity data for JNJ‐46281222 (Farinha et al., 2015). JNJ‐46281222 on its own displayed a submaximal receptor activation of 43 ± 3% in the [35S]‐GTPγS binding assay, with a potency (pEC50 = 6.75 ± 0.08) that is 10‐fold lower compared with its potency to modulate glutamate activity. However, we prefer to refer to JNJ‐46281222 as a PAM and not as a PAM agonist for at least two reasons. Firstly, we cannot fully rule out the presence of endogenous receptor‐bound glutamate. Secondly, the cell line used has a high receptor density, potentially amplifying receptor responses. The potency and affinity of this PAM are higher than any other extensively reported mGlu2 PAMs including JNJ‐40068782 (Table 1; Lavreysen et al., 2013; Trabanco and Cid, 2013). In addition to its valuable properties for in vitro experiments, [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 can also be used for ex vivo mGlu2 receptor occupancy studies, whereas this cannot be carried out with [3H]‐JNJ‐40068782 (Lavreysen et al., 2015).

To investigate the relationship between the orthosteric, allosteric and G protein binding sites, we performed [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding experiments in the absence and presence of either glutamate or GTP. The observation by Lavreysen et al. (2013) and Lundström et al. (2011) – binding of an mGlu2 PAM is enhanced in the presence of a high concentration of the orthosteric agonist glutamate – was taken as a starting point for our work. In our case, the total amount of sites accessible for [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding was significantly enlarged by approximately 2.5‐fold by the addition of glutamate (Figures 3, 4). This indicates a conformational change in receptor structure that increases the population of receptors in a more favourable state for PAM binding and recognition. In addition, we performed [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding experiments in the presence of increasing concentrations of glutamate, confirming the increase in specific binding with a micromolar potency for glutamate (pEC50 = 5.27) and a pseudo‐Hill slope of less than unity (n H = 0.49), indicative of allosteric enhancement of JNJ‐46281222 binding by the agonist. Thereby, this experiment clearly revealed two‐way allosterism between orthosteric and allosteric binding sites (Keov et al., 2011).

We showed that the presence of glutamate does not significantly change the affinity of mGlu2 PAMs, as was observed previously for mGlu5 PAMs (Gregory et al., 2012). Specifically, the affinity of JNJ‐46281222 was not affected by the presence of glutamate, as both K D values were similar (1.7 and 2.4 nM, Table 5), just like the pIC50 values of 7.71 and 7.63 (Table 4). For JNJ‐40068782, we did not find a significant increase in affinity, as shown by the pIC50 values, whereas Lavreysen et al. (2013 showed an increase in K D values. This could be indicative for between membrane pool or between lab variations. The presence of glutamate decreased the rate of both association and dissociation of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 to a small non‐significant extent. Most striking was the ability of glutamate to change the two‐phasic character of dissociation towards a one‐phase dissociation. In general, a two‐phasic character can be explained by the presence of two binding sites, known as the high‐ and low‐affinity binding sites within a receptor population (Christopoulos and Kenakin, 2002). In this case, one could postulate that glutamate increases the number of PAM binding sites and fixes the receptor into a single conformational state resulting in a single dissociation rate.

Previous studies showed that binding of only one PAM per dimer is sufficient for enhancement of receptor activity (Goudet et al., 2005). It was hypothesized that upon receptor activation, only one of the 7TM domains is turned on and activates a G protein (Hlavackova et al., 2005). Whereas these studies came to their conclusions using changes in the receptor structure, we evaluated the number of orthosteric and allosteric binding sites using radioligand saturation binding assays on the WT mGlu2 receptor. Interestingly, saturation binding of the orthosteric agonist [3H]‐DCG‐IV revealed a B max similar to [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 (Table 5), indicating the same number of binding sites for both orthosteric agonists and PAMs. So, whereas only one PAM per receptor dimer is necessary for efficacy (Hlavackova et al., 2005), it seems that two PAMs actually bind the receptor in the absence of glutamate. On the other hand, the presence of glutamate increases the number of allosteric binding sites, as shown by the increased B max of [3H]JNJ‐46281222 (Table 5). This indicates that addition of glutamate might lead to [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding to both glutamate‐bound and ‐unbound receptors. Interestingly, the increase in accessible PAM binding sites induced by the presence of glutamate was not seen the other way around. Both mGlu2 PAMs JNJ‐40068782 and JNJ‐40411813 increased the affinity of [3H]‐DCG‐IV but not its B max value (Lavreysen et al., 2015, 2013).

The presence of GTP decreased [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding by 65%, indicating that PAM binding is dependent on the availability of receptors that are coupled to a G protein. Moreover, the pseudo‐Hill coefficient of less than unity (n H = −0.58) confirms an allosteric rather than competitive effect of GTP on JNJ‐46281222 binding. The necessity of a coupled G protein for PAM binding was further confirmed by saturation binding experiments with [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222, the orthosteric agonist [3H]‐DCG‐IV and antagonist [3H]‐LY341495, showing that approximately fivefold more receptors are labelled by an antagonist than an agonist or PAM radioligand (Figure 4; Table 5). Decades ago, the presence of GTP has already been shown to decrease agonist but not antagonist binding in class A GPCRs (e.g. Williams and Lefkowitz, 1977). For the mGlu2 receptor, this was also shown for the orthosteric agonists DCG‐IV and LY354740, where GTPγS decreased their binding up to 80% with nanomolar potency (Cartmell et al., 1998; Schaffhauser et al., 1998). In our hands, in addition to a reduction in the total binding level, GTP also induced a significant decrease in binding affinity of JNJ‐46281222, whereas it did not change the affinity of JNJ‐40068782 (Table 4). These findings contribute to the idea that different PAMs can have different effects on the interplay between receptor binding sites. To our knowledge, we are the first to describe the necessity for a G protein bound state of the receptor for PAM binding, as shown by the effects of GTP on the binding of [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 to the mGlu2 receptor.

Previous mutagenesis studies revealed the molecular determinants vital for mGlu2 PAM functional activity (Schaffhauser et al., 2003; Rowe et al., 2008; Farinha et al., 2015). However, PAM binding on mutant receptors has not been previously examined. Docking of JNJ‐46281222 into the 7TM mGlu2 receptor model revealed direct interactions with, amongst others, F6433 .36a.40c and N7355 .47a.47c. In order to confirm the proposed binding pose of JNJ‐46281222 within the mGlu2 7TM domain, we performed [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222 binding experiments to transiently transfected mGlu2 receptor mutants F643A3.36a.40c and N735D5.47a.47c. Their binding was reduced evenly and significantly compared with the transiently transfected WT mGlu2 receptor, showing that these amino acid residues are vital for mGlu2 PAM binding. Together, these results indicate that the loss in mGlu2 PAM functional efficacy, exerted by mGlu2 receptor mutants F643A3.36a.40c and N735D5.47a.47c, is caused by a loss of receptor binding.

We have presented hypotheses for the overlap and possible binding mode of mGlu2 PAMs (Tresadern et al., 2010; Farinha et al., 2015). Here, we used MD simulations of JNJ‐46281222 in an active state 7TM mGlu2 model, which confirmed that the binding mode was stable throughout the simulation. We observed movement of W7736 .48a.50c, which is part of a WLAFxPI sequence on TM6 that is conserved across mGlu receptors. The side chain rotated inwards and interacted with the ligand and Y6473 .39a.43c. The 6.48a.50c position is located on TM6 in the transmission switch for class A GPCRs (Deupi and Standfuss, 2011). Rotamer movements of this tryptophan in rhodopsin along with the kink induced by the neighbouring proline contribute to the outward movement of TM6 to permit activation. Also, the movement of W7736 .48a.50c to disturb H‐bonding in the cluster of amino acids involving Y6473 .39a.43c and the conserved water molecule may play a role in the functional activity of class C allosteric modulators (Doré et al., 2014). This is just above the important region for Na+ ion modulation of A2AAR receptors (Liu et al., 2012). Finally, a recent report suggests that activation of mGlu2 dimers proceeds from inactive TM4/5–TM4/5 interaction to TM6–TM6 interaction in the active state (Xue et al., 2015). It seems plausible that inward movement of large side chains on TM6 will enable the rotation of the monomers to the active state. Further work is needed to provide a deeper understanding of the allosteric modulator action on this mGlu2 monomer and the full‐length dimeric receptor.

In conclusion, we have characterized the selective and highly potent mGlu2 PAM JNJ‐46281222 and its corresponding radioligand [3H]‐JNJ‐46281222. Its characteristics make it the preferred PAM radioligand for studying the mGlu2 receptor. The orthosteric agonist glutamate was shown to increase the number of PAM binding sites without affecting the affinity of JNJ‐46281222. The necessity of a coupled G protein was shown by the fact that GTP induced a large decrease in PAM binding and that the number of PAM binding sites, like the orthosteric agonist, was much lower than the number of G protein‐independent antagonist binding sites. Both mutations F643A3.36a.40c and N735D5.47a.47c caused a large decrease in PAM binding, thereby experimentally confirming the binding site as determined from the modelling and molecular dynamic studies. Together, these results contribute to the understanding of the mechanism of PAM binding and effect, which will hopefully contribute to current and future mGlu2 PAM drug discovery programmes.

Author contributions

M. L. J. D., L. P.‐B., G. T., H. L., A. P. IJ. and L. H. H. participated in research design. M. L. J. D., L. P.‐B., G. T., T. M.‐K., I. B., A. A. T. and J. M. C. conducted experiments. M. L. J. D., L. P.‐B. and G. T. performed data analysis. M. L. J. D., L. P.‐B., G. T., H. L., A. P. IJ. and L. H. H. wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Nothing to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Sequence Alignment used to construct mGlu2 receptor 7TM model.

Figure S2 Comparison of the predicted JNJ‐46281222 binding mode with that of NAMs in the mGlu1 (top, yellow) and mGlu5 (bottom, orange) X‐ray structures.

Table S1 Details of Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

This project was financially supported by IWT Vlaanderen (Agentschap voor innovatie door wetenschap en technologie Vlaanderen).

Doornbos, M. L. J. , Pérez‐Benito, L. , Tresadern, G. , Mulder‐Krieger, T. , Biesmans, I. , Trabanco, A. A. , Cid, J. M. , Lavreysen, H. , IJzerman, A. P. , and Heitman, L. H. (2016) Molecular mechanism of positive allosteric modulation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 by JNJ‐46281222. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 588–600. doi: 10.1111/bph.13390.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al (2013). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 170: 1459–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M, Boyd A, Churchill G, Cuthbert M, Drew M, Fielding M, et al (2012). Isoindolone formation via intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction. Org. Process Res. Dev. 16: 741–747. [Google Scholar]

- Berger O, Edholm O, Jähnig F (1997). Molecular dynamics simulations of a fluid bilayer of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine at full hydration, constant pressure, and constant temperature. Biophys. J. 72: 2002–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell J, Adam G, Chaboz S, Henningsen R, Kemp JA, Klingelschmidt A, et al (1998). Characterization of [3H]‐(2S,2′R,3′R)‐2‐(2′,3′‐dicarboxy‐cyclopropyl)glycine ([3H]‐DCG IV) binding to metabotropic mGlu2 receptor‐transfected cell membranes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 123: 497–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH (1973). Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 22: 3099–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Kenakin T (2002). G protein‐coupled receptor allosterism and complexing. Pharmacol. Rev. 54: 323–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid JM, Tresadern G, Duvey G, Lütjens R, Finn T, Rocher J, et al (2014). Discovery of 1‐butyl‐3‐chloro‐4‐(4‐phenyl‐1‐piperidinyl)‐(1H)‐pyridone (JNJ‐40411813): a novel positive allosteric modulator of the metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 57: 6495–6512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid JM, Tresadern G, Vega JA, de Lucas AI, Matesanz E, Iturrino L, et al (2012). Discovery of 3‐cyclopropylmethyl‐7‐(4‐phenylpiperidin‐1‐yl)‐8‐trifluoromethyl[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3‐a]pyridine (JNJ‐42153605): a positive allosteric modulator of the metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 55: 8770–8789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid‐Nuñez JM, Oehlrich D, Trabanco‐Suárez A.A., Tresadern GJ, Vega Ramiro JA, and MacDonald GJ (2010). 1,2,3‐Triazolo[4,3‐a]pyridine derivatives and their use for the treatment or prevention of neurological and psychiatric disorders. WO 2010/130424 A1.

- Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW (2009). Allosteric modulators of GPCRs: a novel approach for the treatment of CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8: 41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Brown D, Alexander R, March R, Morgan P, Satterthwaite G, et al (2014). Lessons learned from the fate of AstraZeneca's drug pipeline: a five‐dimensional framework. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13: 419–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordomí A, Caltabiano G, Pardo L (2012). Membrane protein simulations using AMBER force field and Berger lipid parameters. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8: 948–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deupi X, Standfuss J (2011). Structural insights into agonist‐induced activation of G‐protein‐coupled receptors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21: 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré AS, Okrasa K, Patel JC, Serrano‐Vega M, Bennett K, Cooke RM, et al (2014). Structure of class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 transmembrane domain. Nature 511: 557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinha A, Lavreysen H, Peeters L, Russo B, Masure S, Trabanco AA, et al (2015). Molecular determinants of positive allosteric modulation of the human metabotropic glutamate receptor 2. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172: 2383–2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell MJ, Witkin JM, Falcone JF, Katner JS, Perry KW, Hart J, et al (2011). N‐(4‐((2‐(trifluoromethyl)‐3‐hydroxy‐4‐(isobutyryl)phenoxy)methyl)benzyl)‐1‐methyl‐1H‐imidazole‐4‐carboxamide (THIIC), a novel metabotropic glutamate 2 potentiator with potential anxiolytic/antidepressant properties: in vivo profiling suggests a link betw. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 336: 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galici R, Jones CK, Hemstapat K, Nong Y, Echemendia NG, Williams LC, et al (2006). Biphenyl‐indanone A, a positive allosteric modulator of the metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 2, has antipsychotic‐ and anxiolytic‐like effects in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 318: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet C, Kniazeff J, Hlavackova V, Malhaire F, Maurel D, Acher F, et al (2005). Asymmetric functioning of dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptors disclosed by positive allosteric modulators. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 24380–24385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, Dong EN, Meiler J, Conn PJ (2011). Allosteric modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors: structural insights and therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology 60: 66–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, Noetzel MJ, Rook JM, Vinson PN, Stauffer SR, Rodriguez AL, et al (2012). Investigating metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 allosteric modulator cooperativity, affinity, and agonism: enriching structure–function studies and structure–activity relationships. Mol. Pharmacol. 82: 860–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemstapat K, Costa HD, Nong Y, Brady AE, Luo Q, Niswender CM, et al (2007). A novel family of potent negative allosteric modulators of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322: 254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B, Kutzner C, der van Spoel, D. Darr N, and Lindahl, E. (2008). GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load‐balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4: 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavackova V, Goudet C, Kniazeff J, Zikova A, Maurel D, Vol C, et al (2005). Evidence for a single heptahelical domain being turned on upon activation of a dimeric GPCR. EMBO J. 24: 499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isberg V, de Graaf C, Bortolato A, Cherezov V, Katritch V, Marshall FH, et al (2015). Generic GPCR residue numbers – aligning topology maps while minding the gaps. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 36: 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Baez M, Jagdmann GE, Britton TC, Large TH, Callagaro DO, et al (2003). Discovery of allosteric potentiators for the metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor: synthesis and subtype selectivity of N‐(4‐(2‐methoxyphenoxy)phenyl)‐N‐(2,2,2‐ trifluoroethylsulfonyl)pyrid‐3‐ylmethylamine. J. Med. Chem. 46: 3189–3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keov P, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A (2011). Allosteric modulation of G protein‐coupled receptors: a pharmacological perspective. Neuropharmacology 60: 24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniazeff J, Prézeau L, Rondard P, Pin J‐P, Goudet C (2011). Dimers and beyond: the functional puzzles of class C GPCRs. Pharmacol. Ther. 130: 9–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavreysen H, Ahnaou A, Drinkenburg W, Langlois X, Mackie C, Pype S, et al (2015). Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of JNJ‐40411813, a positive allosteric modulator of the mGlu2 receptor. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 3: e00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavreysen H, Langlois X, Ahnaou A, Drinkenburg W, te Riele P, Biesmans I, et al (2013). Pharmacological characterization of JNJ‐40068782, a new potent, selective, and systemically active positive allosteric modulator of the mGlu2 receptor and its radioligand [3H]JNJ‐40068782. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 346: 514–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindorff‐Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, et al (2010). Improved side‐chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78: 1950–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chun E, Thompson A a, Chun E, Chubukov P, Xu F, et al (2012). Structural basis for allosteric regulation of GPCRs by sodium ions. Science 337: 232–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundström L, Bissantz C, Beck J, Wettstein JG, Woltering TJ, Wichmann J, et al (2011). Structural determinants of allosteric antagonism at metabotropic glutamate receptor 2: mechanistic studies with new potent negative allosteric modulators. Br. J. Pharmacol. 164: 521–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustaine DE, Granier S, Doumazane E, Scholler P, Rahmeh R, Bron P, et al (2012). Distinct roles of metabotropic glutamate receptor dimerization in agonist activation and G‐protein coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109: 16342–16347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto T, Tsuchiya D, Morikawa K, Jingami H (2007). Structures of the extracellular regions of the group II/III metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104: 3759–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Bockaert J, Collingridge GL, Conn PJ, Ferraguti F, Schoepp DD, et al (2011). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: from the workbench to the bedside. Neuropharmacology 60: 1017–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender CM, Conn PJ (2010). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 50: 295–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, Davenport AP, McGrath JC, Peters JA, Southan C, Spedding M, Yu W, Harmar AJ; NC‐IUPHAR. (2014) The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 42 (Database Issue): D1098‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin J‐P, Duvoisin R (1995). The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology 34: 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SGF, DeVree BT, Zou Y, Kruse AC, Chung KY, Kobilka TS, et al (2011). Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor‐Gs protein complex. Nature 477: 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano C, Yang W‐L, O ’Malley KL (1996). Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a disulfide‐linked dimer. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 28612–28616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe BA, Schaffhauser H, Morales S, Lubbers LS, Bonnefous C, Kamenecka TM, et al (2008). Transposition of three amino acids transforms the human metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)‐3‐positive allosteric modulation site to mGluR2, and additional characterization of the mGluR2‐positive allosteric modulation site. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 326: 240–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffhauser H, Richards JG, Cartmell J, Chaboz S, Kemp JA, Klingelschmidt A, et al (1998). In vitro binding characteristics of a new selective group II metabotropic glutamate receptor radioligand, [3H]LY354740, in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 53: 228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffhauser H, Rowe BA, Morales S, Chavez‐Noriega LE, Yin R, Jachec C, et al (2003). Pharmacological characterization and identification of amino acids involved in the positive modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 2. Mol. Pharmacol. 64: 798–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabanco AA, Cid JM (2013). mGluR2 positive allosteric modulators: a patent review (2009–present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 23: 629–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresadern G, Cid JM, Macdonald GJ, Vega JA, de Lucas AI, García A, et al (2010). Scaffold hopping from pyridones to imidazo[1,2‐a]pyridines. New positive allosteric modulators of metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LT, Lefkowitz RJ (1977). Slowly reversible binding of catecholamine to a nucleotide‐sensitive state of the beta‐adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 252: 7207–7213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltering TJ, Wichmann J, Goetschi E, Knoflach F, Ballard TM, Huwyler J, et al (2010). Synthesis and characterization of 1,3‐dihydro‐benzo[b][1,4]diazepin‐2‐one derivatives: part 4. In vivo active potent and selective non‐competitive metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20: 6969–6974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Wang C, Gregory KJ, Han GW, Cho HP, Xia Y, et al (2014). Structure of a class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 bound to an allosteric modulator. Science 344: 58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, Rovira X, Scholler P, Zhao H, Liu J, Pin J‐P, et al (2015). Major ligand‐induced rearrangement of the heptahelical domain interface in a GPCR dimer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11: 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Sequence Alignment used to construct mGlu2 receptor 7TM model.

Figure S2 Comparison of the predicted JNJ‐46281222 binding mode with that of NAMs in the mGlu1 (top, yellow) and mGlu5 (bottom, orange) X‐ray structures.

Table S1 Details of Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

Supporting info item