Abstract

Tea plant (Camellia sinensis) leaf is an important non-alcoholic beverage resource. The application of quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) has a profound significance for the gene expression studies of tea plant, especially when applied to tea leaf development and metabolism. In this study, nine candidate reference genes (i.e., CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB) of C. sinensis were cloned. The quantitative expression data of these genes were investigated in five tea leaf developmental stages (i.e., 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and older leaves) and normal growth tea leaves subjected to five hormonal stimuli (i.e., ABA, GA, IAA, MeJA, and SA), and gene expression stability was calculated using three common statistical algorithms, namely, geNorm, NormFinder, and Bestkeeper. Results indicated that CsTBP and CsTIP41 were the most stable genes in tea leaf development and CsTBP was the best gene under hormonal stimuli; by contrast, CsGAPDH and CsTUB genes showed the least stability. The gene expression profile of CsNAM gene was analyzed to confirm the validity of the reference genes in this study. Our data provide basis for the selection of reference genes for future biological research in the leaf development and hormonal stimuli of C. sinensis.

Quantifying gene expression is a common technique in molecular biology studies. Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) has become the most prevalent method applied to quantify assays of gene expression1,2. The two methods of presenting quantitative gene expression include the absolute and relative quantification methods. Absolute quantification provides an exact copy number of genes by transforming quantification cycle in a standard curve3. Relative quantification presents real-time PCR data of target genes relying on internal control genes as reference4. As knowledge of the copy number of gene is often unnecessary and most researchers focus on the discrepant analysis of gene expression, relative quantification has become a more common and powerful tool for gene expression assays5. Considering its many benefits, however, relative quantification is disadvantaged by the fact that at least one stable internal reference gene must be employed during analysis. Selection of a reliable reference gene under certain conditions is the key to quantitative accuracy.

Many genes are involved in the maintenance of basic cellular functions, such as the cell structure and primary metabolism. Some of these genes, such as the actin7 gene (ACT7), elongation factor-1α gene (EF-1α), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4α-1 gene (eIF-4α), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH), protein phosphatase 2A gene (PP2A), SAND family protein gene (SAND), TATA-box binding protein gene (TBP), Tap42-interacting protein of 41 kDa gene (TIP41), and tubulin beta gene (TUB), have been identified as reliable reference genes in plants6,7. A main assessment criterion for choosing suitable reference genes under certain conditions is that the gene should be stably expressed under the desired test conditions. Given that reference genes do not always show perfectly stable expression in response to a variety of conditions or cross species, reassessment of reference genes under certain conditions is essential to ensure the accuracy of the calculation results in gene expression studies8,9.

Tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) is an important leaf-type woody crop used for the production of non-alcoholic beverages worldwide10,11. Tender tea leaves are rich in beneficial metabolites, including tea polyphenols, theanine, and polysaccharides, which exert positive effects on the prevention of cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases12,13,14,15,16. The concentration of these active substances is usually affected by different leaf development stages and seasonal climates17,18,19. Therefore, tender tea leaves are picked as ideal beverage-processing materials within a suitable season, such as spring and summer. Tea leaves are frequently used as experimental materials in molecular biology studies, including research on the tea leaf transcriptome, metabolomic, and development20,21,22. However, no systematic analysis of reference gene selection for normalization in various tea leaf development stages and hormonal treatments is yet available.

In this study, nine common reference genes (CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB) with high homology to Arabidopsis were cloned and identified in C. sinensis. These nine genes were selected to assess the stability of gene expression in five different developmental stages (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and older leaves) and five different hormonal stimuli (ABA, GA, IAA, MeJA, and SA) in tea plant. Three different statistical algorithms (geNorm23, NormFinder24, and BestKeeper25) were used to calculate the variability of the expression of the candidate genes and obtain the most suitable reference genes. This study provides a basis for the selection of reference genes and useful guidelines for future gene expression studies of C. sinensis.

Results

Cloning and quality control of candidate reference genes

Based on homology analysis with Arabidopsis, the full-length sequences of nine candidate reference genes (CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB) were identified from the C. sinensis transcriptome20. These nine genes were cloned from C. sinensis cv. ‘Longjing43’ (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). The sequence information of these genes is shown in Supplementary Figs S2–S10. The minimal identity of the encoded sequences of all of the genes at the amino acid level to the target homologs exceeded 64%, and five cloned genes showed high identities exceeding 90% (Supplementary Table S1). Specific primer pairs were designed, and confirmed on the basis of the amplification specificity and efficiency results of the candidate reference genes: all primers were amplified with a single PCR product of the expected size by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Fig. S11); single-peak melting curves were obtained in all qPCR amplifications; the amplification efficiency (E) of all reactions ranged from 95.5% to 107.5%; and the correlation coefficients (R2) of the standard curve varied from 0.992 to 0.999 (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S12).

Figure 1. Photograph of the leaf tissue of the tea plant cultivar ‘Longjing43’.

Relative position of leaves from a two-years-old cutting seedling of C. sinensis cv. ‘Longjing43’.

Table 1. Candidate reference genes, primer sequences, and amplicon characteristics of C. sinensis.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Arabidopsis homolog gene | Primer sequence (5′–3′) forward/reverse | Amplicon length (bp) | E (%) | Tm °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsACT7 | Actin7 gene | AT5G09810 | TTGGATTCTGGGGATGGTGTTAGC | 195 | 102.6 | 84.5 |

| AGCAAGTTTCTCTTTCACATCACGG | ||||||

| CsEF-1α | Elongation factor-1α gene | AT5G60390 | TTGACAAGCGTGTGATTGAGAGGT | 177 | 107.0 | 84 |

| GGGCATCAATGACAGTGCAGTAGTA | ||||||

| CseIF-4α | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4α-1 gene | AT3G13920 | TGAGTTACTTGTGGCTGATGGAGAA | 145 | 107.5 | 82 |

| CCTTTGCTGAATTGCAGACGGCTT | ||||||

| CsGAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene | AT1G42970 | CCCTCTAAGTCCTCTCACTCCTCCT | 158 | 95.5 | 84 |

| GTTGCTTGGGCAGCCACTACAT | ||||||

| CsPP2A | Protein phosphatase 2A gene | AT3G21650 | AAGAAGAGGAACTGGCGACGGAAC | 153 | 102.9 | 83.5 |

| CAAACAGGTCCAGCAAACGCAAC | ||||||

| CsSAND | SAND family protein gene | AT2G28390 | GCCTGAACCGTCTTCTGTGGAGT | 184 | 101.9 | 87 |

| CTCAATCTCAGACACACTGGTGCTA | ||||||

| CsTBP | TATA-box binding protein gene | AT1G55520 | GGCGGATCAAGTGTTGGAAGGGAG | 166 | 107.0 | 85 |

| ACGCTTGGGATTGTATTCGGCATTA | ||||||

| CsTIP41 | Tap42-interacting protein of 41 kDa gene | AT4G34270 | TGGAGTTGGAAGTGGACGAGACCGA | 176 | 103.6 | 87 |

| CTCTGGAAAGTGGGATGTTTGAAGC | ||||||

| CsTUB | Tubulin beta-6 gene | AT5G12250 | AATGAGGCTTCTTGTGGGAGGTTTG | 147 | 107.0 | 86.5 |

| GTTATTTCCAGCACCAGACTGACCG |

Expression profiles of candidate reference genes

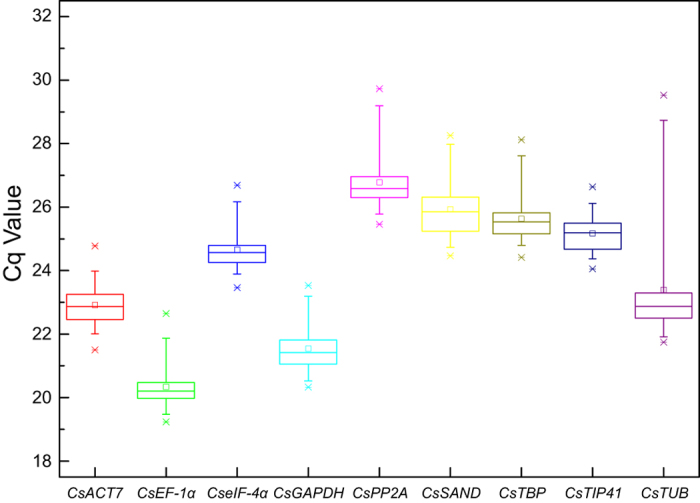

RNA from all tea leaf samples at five developmental stages and five different hormonal stimuli were reverse transcribed into cDNA as templates for qRT-PCR detection. The expression levels of the candidate reference genes were determined by threshold cycle values (Cq) through qRT-PCR experiments (Supplementary Table S2). Cq is the amplification cycle number at which the fluorescence signal reaches above the baseline threshold. Baseline thresholds were standardized to mean 75.55. A box and whiskers plot was used to describe the raw data distribution (Fig. 2). Lower Cq values correspond to higher expression abundance, and higher Cq values correspond to lower expression abundance. At least three genes (CsACT7, CsEF-1α, and CsGAPDH) were highly expressed genes (19 < Cq < 25). Genes CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CseIF-4α showed relatively low expression levels (23 < Cq < 30). The CsTUB gene (standard deviation, SD = 2.21; Cq values varied from 21.74 to 29.53) showed maximum variability, while the other eight tested genes (SD < 1.6) maintained stable expression (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 2. Cq values of nine candidate reference genes in all samples of C. sinensis.

Raw Cq values of ten samples, including five developmental stages of tea plant leaves and five different hormonal stimuli, were described using a box and whiskers plot. The outer box is determined from 25th to 75th percentiles, and the inner box represents the mean value. The line across the box is the median. The whiskers represent percentiles from 5th to 95th, and outliers are depicted by asterisks.

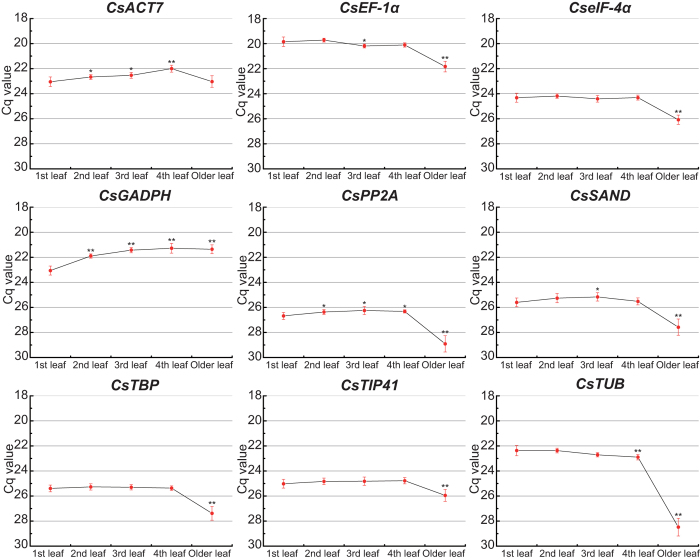

The expression profiles of candidate reference genes during tea leaf developmental stages were investigated (Fig. 3). Seven genes (CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB) were stably expressed in four tender leaves (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th leaves) but showed significantly decreased expression levels in older leaves. The homologs of these genes in Arabidopsis are involved in many biological processes, such as protein translation and extension, cell signaling, and cytoskeleton formation8,26,27,28. Lower expression levels of these genes in aging tea leaves indicate that their biological functions may be partially suppressed. The general trend of expression of two other genes: CsACT7 gene initially increased, and then decreased and restored to the original level in old leaves; CsGAPDH gene increasingly expressed until steadily. The ACT7 gene in Arabidopsis is a basic component of the cytoskeleton and plays an essential role in germination29. The similar gene (CsACT7) of C. sinensis may be involved in the formation of the cytoskeleton in tender leaves; its biological function may also be partially suppressed in older leaves. The GAPDH gene in Arabidopsis is related to glycolysis, microtubule bundling, nuclear RNA transport, DNA replication, and DNA repair30,31. The CsGAPDH gene may be involved in a variety of biological functions during tea leaf development.

Figure 3. Expression profiles of candidate reference genes in various tea leaf developmental stages.

Cq values in five developmental stages of tea plant leaves were counted for expression analysis. Red points represent the mean value of the Cq at a certain developmental stage. Whiskers represent the range of standard errors, and asterisks indicate significant differences in the expression levels of candidate reference genes during tea leaf development (1st leaf as the control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

GeNorm analysis

The expression stabilities of the nine candidate reference genes were analyzed by geNorm software23, which calculates gene expression stability (M) as the average pair-wise variation between all tested genes. The reference gene with the lowest M value was considered as the most stable gene. Ten experimental samples were sorted into three different subsets: “Developmental stages” (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and older leaves), “Hormonal stimuli” (ABA, GA, IAA, MeJA, and SA), and “Total” (all samples). This integration was also adopted in two other statistical algorithms (NormFinder and BestKeeper). The results of GeNorm analysis are detailed in Table 2. Nine reference genes in the three subsets showed high expression stabilities with a threshold value of below 1.5. CseIF-4α and CsEF-1α (M = 0.19) were the most stable genes, while CsTUB (M = 0.90) was the most variable gene in tea leaf developmental stages. Under different hormonal stimuli, CsPP2A and CsTBP (M = 0.19) were identified as the most stable genes, whereas CsGAPDH (M = 0.47) gene showed the worst stability. A combination of individual samples in total showed that CseIF-4α and CsEF-1α (M = 0.20) featured the most stable expression whereas the most variable genes included CsGAPDH (M = 0.59) and CsTUB (M = 0.78).

Table 2. Gene expression stability ranked by geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper.

| Group | Rank | geNorm | NormFinder | BestKeeper | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Stability | Gene | Stability | Gene | SD [±Cq] | CV [%Cq] | ||

| Developmental stages | 1 | CseIF-4α | 0.19 | CsTBP | 0.01 | CsACT7 | 0.42 | 1.84 |

| 2 | CsEF-1α | 0.19 | CsTIP41 | 0.04 | CsTIP41 | 0.45 | 1.81 | |

| 3 | CsTBP | 0.22 | CseIF-4α | 0.05 | CsGAPDH | 0.57 | 2.63 | |

| 4 | CsSAND | 0.28 | CsPP2A | 0.06 | CseIF-4α | 0.58 | 2.36 | |

| 5 | CsPP2A | 0.31 | CsSAND | 0.09 | CsEF-1α | 0.61 | 3.00 | |

| 6 | CsTIP41 | 0.36 | CsEF-1α | 0.12 | CsTBP | 0.66 | 2.58 | |

| 7 | CsACT7 | 0.46 | CsACT7 | 0.16 | CsSAND | 0.75 | 2.91 | |

| 8 | CsGAPDH | 0.63 | CsTUB | 0.17 | CsPP2A | 0.82 | 3.06 | |

| 9 | CsTUB | 0.90 | CsGAPDH | 0.27 | CsTUB | 1.89 | 7.94 | |

| Hormone stimuli | 1 | CsPP2A | 0.19 | CsEF-1α | 0.07 | CseIF-4α | 0.32 | 1.29 |

| 2 | CsTBP | 0.19 | CsTBP | 0.07 | CsEF-1α | 0.34 | 1.69 | |

| 3 | CsSAND | 0.23 | CseIF-4α | 0.07 | CsGAPDH | 0.39 | 1.84 | |

| 4 | CseIF-4α | 0.28 | CsPP2A | 0.08 | CsTIP41 | 0.39 | 1.54 | |

| 5 | CsEF-1α | 0.29 | CsSAND | 0.09 | CsTBP | 0.41 | 1.62 | |

| 6 | CsTUB | 0.33 | CsTIP41 | 0.09 | CsACT7 | 0.45 | 1.94 | |

| 7 | CsTIP41 | 0.37 | CsACT7 | 0.09 | CsPP2A | 0.47 | 1.77 | |

| 8 | CsACT7 | 0.41 | CsTUB | 0.13 | CsTUB | 0.51 | 2.22 | |

| 9 | CsGAPDH | 0.47 | CsGAPDH | 0.23 | CsSAND | 0.52 | 1.99 | |

| Total | 1 | CsEF-1α | 0.20 | CsTBP | 0.06 | CseIF-4α | 0.45 | 1.82 |

| 2 | CseIF-4α | 0.20 | CseIF-4α | 0.06 | CsTIP41 | 0.45 | 1.77 | |

| 3 | CsTBP | 0.26 | CsTIP41 | 0.07 | CsEF-1α | 0.48 | 2.34 | |

| 4 | CsPP2A | 0.31 | CsPP2A | 0.08 | CsACT7 | 0.50 | 2.16 | |

| 5 | CsSAND | 0.33 | CsSAND | 0.10 | CsTBP | 0.51 | 2.01 | |

| 6 | CsTIP41 | 0.37 | CsEF-1α | 0.10 | CsGAPDH | 0.52 | 2.41 | |

| 7 | CsACT7 | 0.46 | CsACT7 | 0.14 | CsPP2A | 0.63 | 2.34 | |

| 8 | CsGAPDH | 0.59 | CsTUB | 0.15 | CsSAND | 0.67 | 2.57 | |

| 9 | CsTUB | 0.78 | CsGAPDH | 0.26 | CsTUB | 1.14 | 4.89 | |

SD [±Cq]: standard deviation of the Cq; CV [%Cq]: coefficient of variance expressed as a percentage of the Cq level.

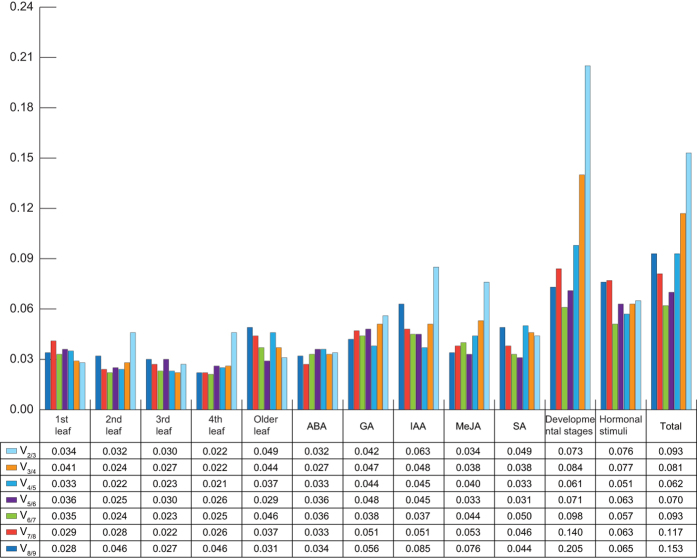

To determine the optimal number of reference genes for accurate normalization, pairwise variations (Vn/n + 1, where n corresponds to the number of reference genes used to normalize gene expression) between two sequential normalization factors (NFn and NFn + 1) were calculated by the geNorm program. A large pairwise variation (the recommended cut-off value ≥0.15) with a significant effect means that the added gene is preferably included for calculation of a reliable normalization factor; an extra reference gene is not required for normalization when the cut-off value is below 0.15. As shown in Fig. 4, the pairwise variations of all experimental samples at the V2/3 value were below 0.15, which indicates that two reference genes were sufficient for accurate normalization; addition of the third reference gene showed no significant effect on the results.

Figure 4. Pairwise variation (V) of candidate reference genes calculated by geNorm.

Pairwise variation (Vn/n + 1) was analyzed between the normalization factors (i.e., NFn and NFn + 1) to determine the optimal number of reference genes. “Developmental stages” include the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and older leaves. “Hormonal stimuli” includes ABA (abscisic acid), GA (gibberellins), IAA (indole-3-acetic acid), MeJA (methyl jasmonate), and SA (salicylic acid). “Total” represents all samples.

NormFinder analysis

The stability value of each candidate reference gene was also calculated by NormFinder software24, which is based on a mathematical model of separate analysis of sample subgroups and estimation of both intra- and intergroup expression variations. Genes with more stable expression were indicated by lower average expression stability values. The results of NormFinder analysis showed that the stability ranking of the nine genes of interest was relatively consistent with the data array of geNorm (Table 2). In NormFinder analysis, the most stable reference gene for the tea leaf developmental stages was CsTBP; CsEF-1α, CsTBP, and CseIF-4α, which featured identical scores, were the most stable genes under different hormonal stimuli. Finally, the most stable reference genes in total were CsTBP and CseIF-4α, which also showed identical scores. The two worst stable genes were, CsTUB and CsGAPDH, were consistently found in the three subsets.

BestKeeper analysis

BestKeeper software25 was applied as an expression standard of reference genes according to the ranking of the standard deviation (SD [±Cq]) and coefficient of variance (CV [%Cq]) of Cq values. The most stable reference genes present the lowest coefficient of variance and standard deviation (CV ± SD). SD values less than 1 were considered an acceptable range of variation25. The analysis results of BestKeeper are also listed in Table 2. Eight reference genes showed remarkably stable expression in all subsets, while the CsTUB gene with CV ± SD values of 7.94 ± 1.89 in “Developmental stages” and 4.89 ± 1.14 in “Total” was considered unacceptable for gene expression normalization. The rankings of Bestkeeper analysis revealed that the most stably expressed genes were CsACT7 (CV ± SD = 1.84 ± 0.42) and CsTIP41 (CV ± SD = 1.81 ± 0.45) for tea leaf developmental stages; this finding contrasts the result that the CsACT7 gene is not a good reference gene in geNorm and NormFinder. CseIF-4α (CV ± SD = 1.29 ± 0.32) and CsEF-1α (CV ± SD = 1.69 ± 0.34) showed the most stable expression under different hormonal stimuli, and CseIF-4α (CV ± SD = 1.82 ± 0.45) and CsTIP41 (CV ± SD = 1.77 ± 0.45) showed the highest expression stabilities in the total subset. Integrating the outcome of above three programs (geNorm, NormFinder, and Bestkeeper), CsTBP and CseIF-4α appear to be the most suitable reference genes in the tea developmental stages, CsTBP may be best reference gene under hormone treatments, and CsTBP and CseIF-4α may be used as the most suitable reference genes in total sample.

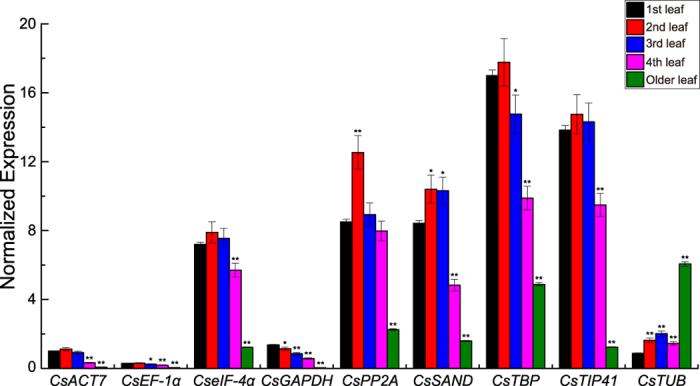

Reference gene validation

The NAM gene belonging to the NAC transcription factor gene family is related to tissue development and stress signal transduction32,33. To validate the reliability of candidate reference genes used in tea leaf development, the relative expression of the tea plant CsNAM gene34 during five tea leaf development stages was normalized by using nine internal control genes (CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB) (Fig. 5). If statistical insignificance is not ignored, the expression levels of the CsNAM gene first increased regularly in the 2nd leaf and then decreased from the 3rd to older leaves when seven internal control genes (CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, and CsTIP41) were used for normalization. Some discrepancies were observed in the normalization of the reference genes. The CsNAM gene was significantly up-regulated in the 2nd leaf when normalized by genes CsPP2A and CsSAND. The CsNAM gene in the 3rd leaf was significantly up-regulated and down-regulated when normalized by genes CsSAND and CsTBP, respectively. The CsNAM gene showed no significant difference in the 4th leaf when normalized by CsPP2A gene. The main discrepancies were observed during normalization of the worst reference genes, CsGAPDH and CsTUB. The CsNAM gene was significantly down-regulated in the 2nd leaf when normalized by the CsGAPDH gene. The up-regulated expression of the CsGAPDH gene in the 2nd leaf may lead to this outcome. When using the reference gene CsTUB, the CsNAM gene showed significant ultra-high expression in older leaf.

Figure 5. Relative quantification of CsNAM gene expression using candidate nine reference genes for normalization during tea leaf developmental stages in C. sinensis.

Results were normalized against the candidate reference genes of C. sinensis. Asterisks indicate significant differences in the expression levels of the CsNAM gene during tea leaf development (1st leaf as the control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

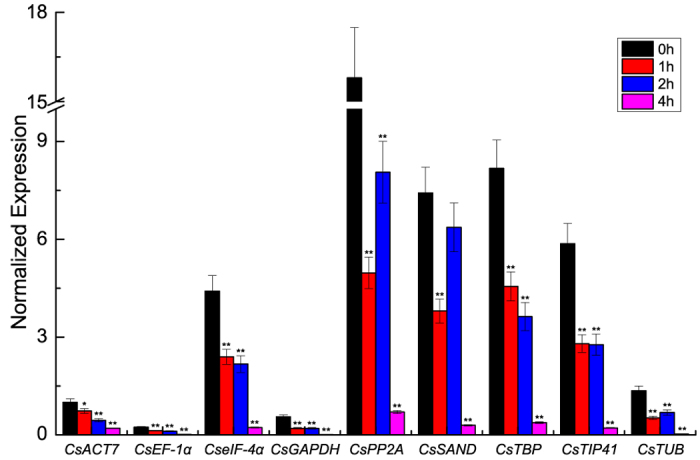

Normalization of the relative expression of the tea plant CsNAM gene under GA treatment was performed by using nine candidate reference genes to validate the reliability of candidate reference genes used for hormonal stimulation (Fig. 6). The main divergence of results was observed in the expression levels of the CsNAM gene between 1 h and 2 h of GA treatment. Two cases may describe this difference: (1) the expression of the CsNAM gene gradually decreased from 0 h to 4 h when normalized by CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsTBP, and CsTIP41 and (2) the expression of the CsNAM gene first decreased at 1 h and then increased at 2 h when normalized by genes CsPP2A, CsSAND, and CsTUB. In the first case, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, and CsTBP were stably expressed genes in NormFinder analysis. In the second case, CsPP2A and CsSAND were stably expressed genes in geNorm analysis. However, three genes CsPP2A, CsSAND, and CsTUB were identified as the worst reference genes in BestKeeper. Thus, the first case is more credible and the genes CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, and CsTBP are the most suitable for normalization of the CsNAM gene under GA treatment.

Figure 6. Relative quantification of CsNAM gene expression under GA treatment using nine candidate reference genes for normalization in C. sinensis.

Results were normalized against the candidate reference genes of C. sinensis. Asterisks indicate significant differences in the expression levels of CsNAM gene under GA treatment (0 h treatment as the untreated control, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Discussion

qRT-PCR is a revolutionary technology used for accurate and sensitive detection in gene expression assay35,36. Besides analysis of animals, yeast, and bacteria, this technology has been used identify reference genes to analyze plant gene expression, including discrepant expression during tissue development and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses8,37. Using a valid internal control gene as a reference will ensure the real-time PCR data to be reliable for target genes; the use of an invalid reference gene will result in deviation. In this study, we cloned nine common internal control genes of tea plant, i.e., CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB, for expression normalization in ten different samples, including five tea leaf developmental stages and five different hormonal stimuli. This study is the first to report the systematic analysis of reference genes that can be used in tea leaf development and hormonal treatment.

During qRT-PCR analysis, stable expression and suitable expression abundance for identifying valid reference genes are reliable precondition to reduce potential risks in different experimental conditions or among diverse species38. For instance, the GAPDH gene shows high stability in Coffea arabica but low stability in peach; TUB is the most stable gene in carrot leaves but the worst stable gene in berry development6,39,40,41. Moreover, as the expression level of the UBI-1 gene in pepper is very low, this gene has been discarded as a reference gene42. The 18S gene in maize grains with excessive expression abundance is not suitable for normalization of lowly expressed genes43. Fortunately, nine candidate reference gene of C. sinensis with reasonable abundance (19 < Cq < 30) were further assessed for expression normalization.

Considering that an algorithm is one-sided for evaluating the expression stability of reference genes, many statistical approaches are usually integrated to determine the best reference genes in different experimental conditions44,45. In the present study, we employed three common statistical programs, geNorm, NormFinder, and Bestkeeper, to evaluate gene expression stability among three different subsets, namely, “Developmental stages”, “Hormonal stimuli”, and “Total”. As expected, the distinct statistical algorithms generated inconsistent stability ranking among the three subsets. The geNorm algorithm determines gene expression stability by comparing the expression ratio of pair-wise gene among test samples23. Co-regulated genes with similar expression profiles will obtain preferential stability ranking from geNorm, leading to an erroneous choice for normalization. By contrast, the algorithms of NormFinder and Bestkeeper are less sensitive to co-regulation24,25. To investigate whether potential co-regulation in two pairs of genes (CseIF-4α/CsEF-1α and CsPP2A/CsTBP) affects the outcome of geNorm, genes among the four genes were differently removed in geNorm. Results showed that removing the top-ranked gene CseIF-4α or CsEF-1α will change the stability ranking of gene expression; removing the top-ranked gene CsPP2A or CsTBP does not markedly change in the stability ranking of gene expression only if gene CseIF-4α or CsEF-1α is lacking. This result indicates that the outputs of the best genes, namely, CseIF-4α and CsEF-1α from geNorm may be affected by their potential co-regulation. Therefore, re-integrating the outcome of programs geNorm, NormFinder, and Bestkeeper, CsTBP and CsTIP41 are the most suitable reference genes in tea leaf developmental stages, CsTBP is the best reference gene under different hormonal stimuli, and CsTBP and CsTIP41 genes can be used as the most suitable reference genes in total sample. The worst stable gene, CsTUB or CsGAPDH, was consistent in geNorm and NormFinder. CsTUB gene was discarded for normalization of tea leaf developmental stages since the SD of its expression exceeded the threshold value (SD > 1) in Bestkeeper.

To validate the availability of a reference gene, the expression levels of CsNAM gene during various tea leaf developmental stages and under GA treatment were detected using nine candidate reference genes for normalization. For tea leaf development, the normalization results of CsNAM gene were more consistent when genes with stable expression were used as internal controls. The two worst reference genes, CsGAPDH and CsTUB, resulted in significant differences in the normalization of the CsNAM gene. For GA treatment, the expression levels of the CsNAM gene showed similar trends upon normalization by some stable and unstable genes. This result may be explained by the fact that several candidate genes may be suitable for normalization; the expression trend of verified genes may also make up for the defects of unstable genes during normalization. Interestingly, the verification procedures described above confirmed that the more stable CsTBP gene is a reliable reference gene that could be available for tea leaf development and hormonal treatments.

Methods

Plant material and treatments

Two-year-old cutting seedlings of tea plant (C. sinensis cv. ‘Longjing43’) were planted in pots containing a mixture of perlite, vermiculite, and sphagnum (ratio, 1:2:3) in a climate-controlled growth chamber programmed with 70% ± 10% relative humidity, 16 h light (25 °C) with a light intensity of 300 μmol·m−2·s−1 during the daytime, and 8 h darkness (16 °C) during the nighttime (Supplementary Fig. S1). The 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and older leaves at different levels of development were collected (Fig. 1). The 3rd leaves were selected as materials for using in hormonal treatments and untreated control to unify standards. Leaves were sprayed with 1 mM gibberellins (GA treatment), 1 mM 3-indoleacetic acid (IAA treatment), 1 mM salicylic acid (SA treatment), 1 mM methyl jasmonate (MeJA treatment), or 0.1 mM abscisic acid (ABA treatment) for 2 h46,47. While GA, IAA, SA, and MeJA were dissolved in distilled water with 2% absolute ethanol, ABA was dissolved in distilled water only. Three biological experimental replicates were performed in different pots for each treatment. Tea plant leaf materials were collected, quickly immersed in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C for RNA extraction.

RNA isolation and cDNA reverse transcription

Total RNA was extracted by using the Quick RNA Isolation Kit (Huayueyang Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). RNA concentration and purity were estimated by a Nanodrop ND 1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and RNA integrity was checked by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. cDNAs (20 μL) were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the PrimeScriptTM RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa Biotech Co., Ltd., Dalian, China).

Selection of candidate reference genes, primer design, and gene cloning

Nine common reference genes, namely, ACT7, EF-1α, eIF-4α, GAPDH, PP2A, SAND, TBP, TIP41, and TUB, were selected from Arabidopsis genes of the TAIR database (http://www.arabidopsis.org). In the present study, potential homologues of the nine reference genes (i.e., CsACT7, CsEF-1α, CseIF-4α, CsGAPDH, CsPP2A, CsSAND, CsTBP, CsTIP41, and CsTUB) used for gene expression analyses were obtained by querying the C. sinensis transcriptome database20. All primers for cloning and detection of reference genes were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software. The primer sequences used in this study are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. The full-length sequences of nine candidate reference genes from C. sinensis were cloned using 2 × Taq Plus Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) as the polymerase. The reaction volume for PCR amplification was 20 μL, including 10 μL of 2 × Taq Plus Master Mix, 7 μL of ddH2O, 1 μL of the template cDNA, and 1 μL of each primer (10 nmol·mL−1). PCR was performed as follows: 5 min at 94 °C for denaturation; 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C (denaturation), 30 s at 52 °C (annealing), and 90 s at 72 °C (extension); and a final step of 10 min at 72 °C for extension. PCR products were gel-purified, ligated into the pMD 19-T vector, and then transformed into Escherichia coli. The bacterial liquids were sequenced by GenScript Corporation (Nanjing, China).

qRT-PCR assay

qRT-PCR reactions were performed in a 96-well plate on a real-time PCR Bio-Rad iQ5 platform (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Tli RNaseH Plus) (TaKaRa Biotech Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 10 μL of SYBR Green I Mix, 2 μL of diluted cDNA (18 × dilution), 0.4 μL of each primer (10 nmol·mL−1), and 7.2 μL of ddH2O. The amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 20 s. Melting curves were obtained to verify primer specificity through stepwise heating of the amplicon from 65 °C to 95 °C. All qRT-PCR assays included three technical and biological replicates. Standard curves were drawn to determine the amplification efficiency (E) and correlation coefficient (R2) of the diluted series on the basis of the diluted cDNA series (10× , 102× , 103× , 104× , 105× , and 106× dilutions). The equation (E = (10[−1/slope] – 1) × 100%) was used to calculate the PCR efficiency48.

Data analysis

Cq values of fluorescence curves were obtained by standardizing the baseline threshold to mean 75.55. The raw Cq data are listed in the Supplementary Table S2. Three common software (i.e., geNorm23, NormFinder24, and BestKeeper25) were used to calculate the expression stability of candidate reference genes. Cq values were converted to relative quantities according to the formula: 2−ΔCt (ΔCt = the corresponding Cq value – minimum Cq)5. geNorm and NormFinder calculations are based on these converted quantities; raw Cq values were directly analyzed by BestKeeper. Pairwise variation values were calculated by geNorm software with a recommended cut-off value ≥0.15. In addition, the CsNAM gene of C. sinensis34 was analyzed to validate the reliability of the candidate reference genes. The statistical tests of gene expression data used in Figs 3, 5, and 6 were calculated by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance is considered at *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. Variance analyses were performed based on the EXCEL program.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wu, Z.-J. et al. Selection of suitable reference genes for qRT-PCR normalization during leaf development and hormonal stimuli in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Sci. Rep. 6, 19748; doi: 10.1038/srep19748 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31200520; 31570691).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.Z. and Z.J.W. initiated and designed the research. Z.J.W. and J.Z. performed the experiments. Z.J.W., C.T., Q.J., X.H.L. and J.Z. analyzed the data. J.Z. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. Z.J.W. wrote the paper. J.Z. and Z.J.W. revised the paper.

References

- Ginzinger D. G. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: an emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp Hematol 30, 503–512 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derveaux S., Vandesompele J. & Hellemans J. How to do successful gene expression analysis using real-time PCR. Methods 50, 227–230 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong D. T. et al. Absolute quantification of gene expression in biomaterials research using real-time PCR. Biomaterials 28, 203–210 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29, e45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C. et al. Selection of suitable reference genes for qPCR normalization under abiotic stresses and hormone stimuli in carrot leaves. PLoS ONE 10, e0117569 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q. et al. Selection of suitable reference genes for qPCR normalization under abiotic stresses in Oenanthe javanica (BI.) DC. PLoS ONE 9, e92262 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T., Stitt M., Altmann T., Udvardi M. K. & Scheible W.-R.d. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139, 5–17 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci A. R., Tanzarella O. A., E. P. & M. C. Identification and validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR normalization in wheat. BMC Mol Biol 10, 11 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang W. P. et al. Varietal identification of tea (Camellia sinensis) using nanofluidic array of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. Hortic Res 1, 14035 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. et al. Exogenous abscisic acid significantly affects proteome in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) exposed to drought stress. Hortic Res 1, 14029 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordoni A. et al. Green tea protection of hypoxia/reoxygenation injury in cultured cardiac cells. J Nutr Biochem 13, 103–111 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levites Y., Youdim M. B. H., Maor G. & Mandel S. Attenuation of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappa B) activation and cell death by tea extracts in neuronal cultures. Biochem Pharmacol 63, 21–29 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D. U. et al. Effect of drinking green tea on age-associated accumulation of Maillard-type fluorescence and carbonyl groups in rat aortic and skin collagen. Arch Biochem Biophys 397, 424–429 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. D., Hong J., Yang G. Y., Liao J. & Yang C. S. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by polyphenols: evidence from laboratory investigations. Am J Clin Nutr 81, 284s–291s (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. S., Wang X., Lu G. & Picinich S. C. Cancer prevention by tea: animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat Rev Cancer 9, 429–439 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song R., Kelman D., Johns K. L. & Wright A. D. Correlation between leaf age, shade levels, and characteristic beneficial natural constituents of tea (Camellia sinensis) grown in Hawaii. Food Chem 133, 707–714 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Y. et al. Seasonal climate effects on flavanols and purine alkaloids of tea (Camellia sinensis L.). Eur Food Res Technol 233, 1049–1055 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. et al. Relationship between gene expression and the accumulation of catechin during spring and autumn in tea plants (Camellia sinensis L.). Hortic Res 2, 15011 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. J., Li X. H., Liu Z. W., Xu Z. S. & Zhuang J. De novo assembly and transcriptome characterization: novel insights into catechins biosynthesis in Camellia sinensis. BMC Plant Biol 14, 277 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y. et al. TMDB: A literature-curated database for small molecular compounds found from tea. BMC Plant Biol 14, 243 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaundun S. & Matsumoto S. Development of CAPS markers based on three key genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway in tea, Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze, and differentiation between assamica and sinensis varieties. Theor Appl Genet (TAG) 106, 375–383 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J. et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 3, research0034 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen C. L., Jensen J. L. & Ørntoft T. F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res 64, 5245–5250 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W., Tichopad A., Prgomet C. & Neuvians T. P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper-Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol Lett 26, 509–515 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N. & Hinnebusch A. G. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136, 731–745 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand C. et al. Arabidopsis HAF2 gene encoding TATA-binding protein (TBP)-associated factor TAF1, is required to integrate light signals to regulate gene expression and growth. J Biol Chem 280, 1465–1473 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastuglia M. et al. γ-tubulin is essential for microtubule organization and development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 1412–1425 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland L. U., Pawloski L. C., Kandasamy M. K. & Meagher R. B. Arabidopsis actin gene ACT7 plays an essential role in germination and root growth. Plant J 33, 319–328 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi M. et al. Nuclear accumulation of cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in cadmium-stressed Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol 162, 333–346 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffagnini M., Fermani S., Costa A., Lemaire S. D. & Trost P. Plant cytoplasmic GAPDH: redox post-translational modifications and moonlighting properties. Front Plant Sci 4, 450 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunieda T. et al. NAC family proteins NARS1/NAC2 and NARS2/NAM in the outer integument regulate embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 2631–2642 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. K. et al. Transcriptional regulation by an NAC (NAM-ATAF1,2-CUC2) transcription factor attenuates ABA signalling for efficient basal defence towards Blumeria graminis f. sp hordei in Arabidopsis. Plant J 56, 867–880 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A., Muoki R. C., Singh K. & Kumar S. CsNAM-like proteinencodes a nuclear localized protein and responds to varied cues in tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze]. Gene 502, 69–74 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. A. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J Mol Endocrinol 29, 23–39 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubista M. et al. The real-time polymerase chain reaction. Mol Asp Med 27, 95–125 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenin S. et al. Normalization of qRT-PCR data: the necessity of adopting a systematic, experimental conditions-specific, validation of references. J Exp Bot 60, 487–493 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H. J. et al. Selection of appropriate reference genes for gene expression studies by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in cucumber. Anal Biochem 399, 257–261 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalobres-Cavallari C. F., Severino F. E., Maluf M. P. & Maia I. G. Identification of suitable internal control genes for expression studies in Coffea arabica under different experimental conditions. BMC Mol Biol 10, 1 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z. G., Gao Z. H., Wang F., Zhou J. & Zhang Z. Selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression studies in peach using real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol 10, 71 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid K. E., Olsson N., Schlosser J., Peng F. & Lund S. T. An optimized grapevine RNA isolation procedure and statistical determination of reference genes for real-time RT-PCR during berry development. BMC Plant Biol 6, 27 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H. et al. Identification of reference genes for reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR normalization in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Biochem Bioph Res Co 416, 24–30 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli V., Messias R. d. S., Silva S. r. D. d. A. e. & Rombaldi C. V. Selection of reliable reference genes for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction studies in maize grains. Plant Cell Rep 32, 1869–1187 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. L. et al. Selection and evaluation of novel reference genes for quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) based on genome and transcriptome data in Brassica napus L. Gene 538, 113–122 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro F., Sebastiana M., Pais M. S. & Figueiredo A. Reference gene selection and validation for the early responses to downy mildew infection in susceptible and resistant Vitis vinifera cultivars. PLoS ONE 8, e72998 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J.-Y. Cloning of a new glutathione peroxidase gene from tea plant (Camellia sinensis) and expression analysis under biotic and abiotic stresses. Botanical Studies 55, 7 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana N. K., Mohanpuria P. & Yadav S. K. Cloning and characterization of a cytosolic glutamine synthetase from Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze that is upregulated by ABA, SA and H2O2. Molecul Biotechnol 39, 49–56 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radonic A. et al. Guideline to reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem Bioph Res Co 313, 856–862 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.