Abstract

The multifactorial etiology of massive Crassostrea gigas summer mortalities results from complex interactions between oysters, opportunistic pathogens and environmental factors. In a field survey conducted in 2014 in the Mediterranean Thau Lagoon (France), we evidenced that the development of the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella, which produces paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs), was concomitant with the accumulation of PSTs in oyster flesh and the occurrence of C. gigas mortalities. In order to investigate the possible role of toxic algae in this complex disease, we experimentally infected C. gigas oyster juveniles with Vibrio tasmaniensis strain LGP32, a strain associated with oyster summer mortalities, after oysters were exposed to Alexandrium catenella. Exposure of oysters to A. catenella significantly increased the susceptibility of oysters to V. tasmaniensis LGP32. On the contrary, exposure to the non-toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense or to the haptophyte Tisochrysis lutea used as a foraging alga did not increase susceptibility to V. tasmaniensis LGP32. This study shows for the first time that A. catenella increases the susceptibility of Crassostrea gigas to pathogenic vibrios. Therefore, in addition to complex environmental factors explaining the mass mortalities of bivalve mollusks, feeding on neurotoxic dinoflagellates should now be considered as an environmental factor that potentially increases the severity of oyster mortality events.

Keywords: harmful algae, environment, interaction, pathogens, defense, paralytic shellfish toxin

1. Introduction

The mortality of the juvenile pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas is the result of complex interactions between oysters, their environment and opportunistic pathogens. It is a global phenomenon that has been observed several times in marine systems of different countries, including Brazil, the USA [1,2] and recently reported in New Zealand, Australia and Europe [3,4,5,6]. In France, high C. gigas mortality rates (60%–100%) have been reported since 1991. They are of major concern to oyster farmers [7,8] due to the important economic losses. Pathogenic populations of Vibrio from the Splendidus clade have been associated with the recurrent “summer mortality” outbreaks in C. gigas juveniles [9,10,11,12,13]. Among them is Vibrio tasmaniensis LGP32 [10], whose pathogenic processes have been characterized in detail [14,15,16]. The ostreid herpes virus OsHV-1 μVar was also associated with abnormal mortalities of C. gigas in France [17,18]. It is believed that abiotic factors enhance the susceptibility of oysters to infections by various pathogens, such as bacteria and viruses [9,10,19]. Temperature was actually found to be one major driving environmental factor influencing oyster mortality [20]. However, when considered individually, pathogens, temperature, reproductive effort, diet and farming practices donot account for the global increase in oyster mortalities in recent years [20,21,22,23].

C. gigas oysters, like other bivalve mollusks, are filter feeders that feed on micro-phytoplankton, including toxic dinoflagellates. Among these dinoflagellates, Alexandrium catenella, a paralytic shellfish toxin (PST) producer, is observed worldwide [24]. Extensive blooms of this species have been reported in various marine environments, such as the Pacific Ocean of North America [25], Chile [26], New Zealand [27], Japan, China, South Korea [28,29] and the western Mediterranean Sea [30,31]. In the Mediterranean Sea, blooms of A. catenella were observed in confined areas, such as lagoons and harbors [32,33]. Since 1998, several A. catenella blooms were observed in spring and/or autumn in the Mediterranean ThauLagoon (France, N 43°25′, E 03°39′), a shallow lagoon open to the sea and holding an important oyster (C. gigas) production (10,000 tones·year−1) [34,35,36,37,38]. In Thau Lagoon, A. catenella could reach high densities during bloom periods (3 × 106–14 × 106 cells·L−1) with toxin contamination in bivalves frequently exceeding the sanitary threshold over which the bivalves are considered dangerous for consumption [39].

It is now established that exposure of mollusks to high concentrations of PST-producing dinoflagellates could negatively affect the feeding, burrowing and survival of these bivalves [40,41,42,43]. Paralytic shellfish toxin (PST) producers are known to negatively affect the physiological and cellular processes of oysters, such as filtration and digestion [44,45,46,47]. Feeding on these neurotoxic dinoflagellates leads to an accumulation and biotransformation of PSTs mainly in the digestive gland [48,49]. Interestingly, these potent toxic algae impact the oyster immune system and induce an increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and an inhibition of hemocyte phagocytosis [50,51,52]. Importantly, Medhioub et al. (2013) showed that the PST-producing A. catenella induces apoptosis in C. gigas hemocytes [53]. More recently, it has been shown that exposure to a toxic strain of A. catenella modifies the host-pathogen interaction by reducing the prevalence of OsHV-1 μvar infection [54]. However, the effects of A. catenella on the susceptibility of juvenile oysters to the bacterial pathogens involved in the summer mortality disease have not been investigated to date.

Here, we conducted a field study to investigate the relationship between the dynamics of A. catenella in the water column, the bioaccumulation of PSTs in oyster flesh and their mortality in the Thau Lagoon. The detection of PSTs in the flesh of oysters during a mortality event prompted us to investigate the negative effects of toxic algae on oyster susceptibility to pathogenic vibrios. In agreement with our field observations, controlled experiments showed that an exposure of C. gigas to A. catenella significantly impacts the survival of these mollusks when further infected with the pathogenic V. tasmaniensis strain LGP32.

2. Results

2.1. Occurrence of an Oyster Mortality Event during a Toxic Alexandrium catenella in the Thau Lagoon

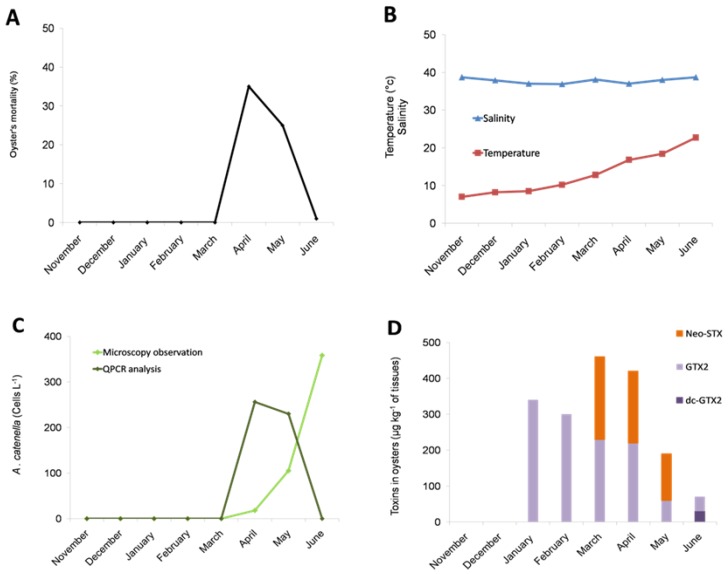

We monitored the dynamics of toxic algae in the Thau in 2014, when a massive mortality of oyster juveniles occurred in April and May, as recorded in the French Shellfish Observatory Network database (RESCO for Réseau d'observations conchylicoles) (Figure 1A). The mortality event occurred when the seawater temperature was between 13 °C and 17 °C (Figure 1B). Interestingly, A. catenella cells were observed in the water column from the Thau Lagoon in April, May and June 2014 at concentrations of 18, 105 and 358 cells·L−1, respectively, when the mortality event occurred (Figure 1C). The identification of A. catenella DNA in April and May 2014 at concentrations corresponding to 256 and 230 cells·L−1, respectively, was confirmed by qPCR amplification (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Field survey inside an oyster farm in Thau Lagoon in 2014. Oyster mortality (A); water temperature and salinity (B); abundance of A. catenella in water (C); accumulation of paralytic shellfish toxins in surviving oysters (D). The bar charts represent (in %) the temporal toxin in oysters. (Neo-STX for neosaxitoxin, GTX2 for gonyautoxin 2 and dc-GTX2 for decarbamoyl gonyautoxin 2).

In addition to the presence of A. catenella in the water column, PSP toxins were detected in the flesh of juvenile oyster cultured in the Thau Lagoon. Importantly, neosaxitoxin (Neo-STX) was detected at high rates (up to 460 μg/kg of oyster flesh) in March, April and May 2014 concomitantly with the detection of A. catenella in the environment (Figure 1D). Interestingly, when mortality occurred (April–May 2014), the PSP rates tended to decrease in surviving oysters with no more Neo-STX being detected in June 2014, at the end of the mortality event. After the mortality event, in June 2014, neo-STX was no longer detected in surviving oysters; only low rates of gonyautoxin 2 (GTX2) and decarbamoyl gonyautoxin (dc-GTX2) were detected.

2.2. Exposure to Alexandrium catenella Increases Oyster Mortality

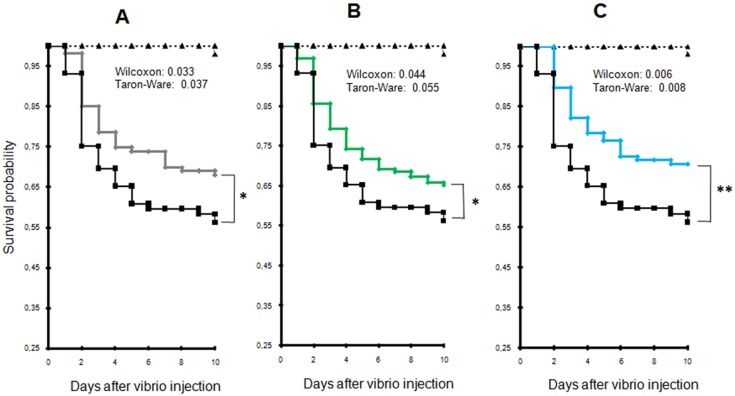

To determine whether the presence of Alexandrium catenella could increase oyster mortality, juvenile oysters were exposed for 48 h either to the toxic strain of A. catenella (ACT03) or to A. tamarense (ATT07) or T. lutea used as foraging algae. Algal density was monitored in tanks all over the experiments showing similar concentrations in tanks during the time of experiment exposure (Figure S1). After a 24 h exposure to algae, oysters were injected with a lethal dose of Vibrio tasmaniensis LGP32 or sterile seawater (SSW), and oyster mortality was monitored for 10 days after their infection. We observed a significant increase in the mortality of oysters previously exposed to the toxic dinoflagellate A. catenella in comparison to individuals that were starved or exposed to A. tamarense or T. lutea (p = 0.033, 0.044 and 0.006, Wilcoxon test, respectively) (Figure 2). The LD30 (lethal dose 30%) was reached at Day 3 for animals previously fed with A. catenella, while it occurred at Days 7, 6 and 9 for oysters starved, fed with A. tamarense or fed with T. lutea, respectively. In other words, at Day 10, the mortality of oysters that were previously exposed to A. catenella was 35%, 27% and 53% higher than that of oysters unfed or fed with A. tamarense or T. lutea, respectively. In the absence of infectious challenge, no mortalities were recorded over 10 days for control animals injected with sterile sea water (SSW), for starved oysters and for oysters fed with A. catenella, A. tamarense or T. lutea.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Kaplan-Meier survival curves generated for oysters exposed to different algae and for starved mollusks. (A) Oysters fed Alexandrium catenella versus starved animals; (B) oysters fed A. catenella versus those fed Alexandrium tamarense; (C) oysters fed A. catenella versus those fed Tisochrysis lutea. A. catenella (black); A. tamarense (green); T. lutea (blue). Control oysters that were not infected by Vibrio tasmaniensis LGP32 or were injected with sterile seawater (SSW) are represented in black dashed triangles. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

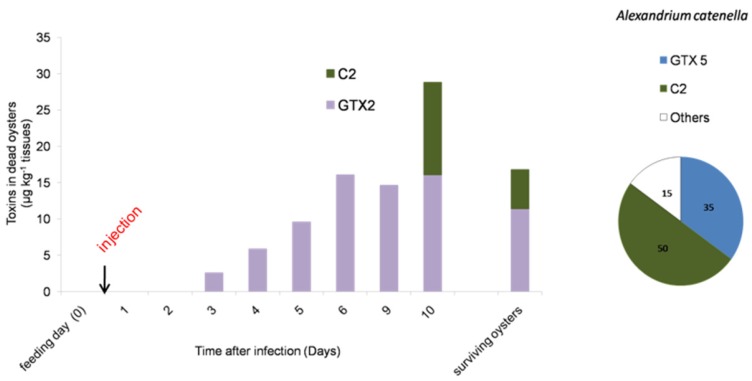

2.3. PSTs Accumulate in Infected Oysters

The Alexandrium sp. used in our experiment were controlled for their PST content. The ACT03 strain showed a toxin amount of 5.3 ± 0.4 pg toxins·cell−1. The specific toxicity of this strain was 1 ± 0.1 pg STX equivalent·cell−1. The ACT03 PST profile was characterized by the presence of carbamate, decarbamoyl and N-sulfocarbamoyltoxins. The following toxins were detected in decreasing concentrations: N-sulfocarbamoyltoxin 2 C2 (50%), GTX5 (35%), GTX4 (12%), GTX1 (1%) and Neo-STX (1%), with STX and dc-STX, GTX2, GTX3 and C4 present as trace amounts (Figure 3). No toxins were found in the Alexandrium tamarense strain (ATT07). In order to monitor the PST profile in oysters in our controlled experiment, dead oysters fed with A. catenella and infected with V. tasmaniensis were collected every day. PSTs were not detected in the most sensitive oysters, which died after one and two days of incubation. PSTs were detected in dead oysters after three days of incubation (Figure 3). Then, the toxicity level increased to reach 29 ± 7 μg·kg−1 tissue wet weight at Day 10. Moreover, the toxin profile displayed a substantial change in comparison to that of A. catenella cells (Figure 3). Among the toxins produced by A. catenella, only C2 was detected in oysters 10 days after the beginning of the experiment. GTX2, which was present as a trace in A. catenella cells, represented 100% of the total toxins measured in oysters that died at Days 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 and was the major toxin compound (57%) at the end of the experiment (Day 10). Interestingly, the toxicity level reached 17 ± 5 μg·kg−1 tissue wet weight in oysters considered as survivors 12 days after the infection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Evolution of the paralytic shellfish toxin content (μg·kg−1 wet weight of mollusk) in dead oysters during the Vibrio tasmaniensis LGP32 infection experiment. The bar charts represent (in %) the temporal toxin in oysters. The pie charts represent (in %) the toxin composition of Alexandrium catenella. (C2 for N-sulfocarbamoyltoxin 2, GTX2 for gonyautoxin 2 and GTX5 for gonyautoxin 5).

3. Discussion

Results from our laboratory experiments demonstrated that exposure to the neurotoxic Alexandrium catenella increases the susceptibility of Crassostrea gigas oysters to the pathogenic V. tasmaniensis LGP32. Indeed, a significant increase in oyster mortality induced by Vibrio infection was observed after exposure to A. catenella. Interestingly, we earlier showed that this toxic dinoflagellate induces the apoptosis of C. gigas hemocytes (immune cells) at PST concentrations similar to those generally observed in situ during a bloom of toxic algae [53]. Apoptosis was observed 24 h after exposure to A. catenella, which corresponds to the time we used for oyster infection in our experiment. Such destruction of the hemocytes, which play a key role in the defense mechanism of invertebrates [55], could strongly affect the capacity of C. gigas to resist bacterial infection and be responsible for the increased susceptibility of oysters observed here. Contrary to our results, exposure to A. catenella was shown to reduce the infection of oysters by the OsHV-1 herpesvirus [54]. The different susceptibility of oysters to those different pathogens is probably due to different immune reactions required to control bacterial and viral pathogens [56]. It can indeed be hypothesized that PSTs polarize the oyster immune response by triggering immune mechanisms that predispose to bacterial infections, but protect from viral infections. However, the potential lytic activity of the ACT03 strain towards hemocytes due to allelochemical compounds could not be ruled out and must be considered as an additional factor increasing the sensitivity of oysters to pathogens [57].

Supporting our hypothesis of a negative effect of toxic algae on oyster immunity, we observed an accumulation of toxins in the flesh of oyster batches showing higher mortality rates. Interestingly, no PSTs were found during the first and the second day of the incubation in the tissues of dead oysters that were fed with A. catenella and infected with V. tasmaniensis. GTX2, which was absent in the ACT03 cells, appeared in dead oysters three days after infection, and its concentration increased continuously until the 10th day of experimental exposure and during the in situ exposure. Data showed differences between toxins in the ingested A. catenella cells and those found in fed oysters. This could be attributed to a selective uptake of the toxins in oyster tissues, metabolic interconversion and elimination of the toxins [47,58,59,60]. Several studies suggested that an active biotransformation/interconversion of PSTs occurred [58,61]. The toxins that were accumulated in oysters in the experimental infection or in oyster individuals exposed in situ to natural A. catenella blooms can result from the transformation of some toxins (GTX3, C2 and others) produced by this dinoflagellate. This suggests that an important biotransformation process occurred in the C. gigas tissues. In our experiments, C2 and GTX2 accumulated in surviving oysters (Figure 3). We can speculate that these toxins, resulting from biotransformation, may have low toxicity and presumably did not affect the capacity of oysters to resist vibrio infection.

One important finding from this study is that C. gigas mortality observed in 2014 occurred while oyster flesh was contaminated by PSTs. These results correspond to previous works showing that PSTs were present at concentrations as high as 920 μg·kg−1 of digestive gland wet weight in oysters exposed to toxic algae in Thau Lagoon in May 2011 [62] when oyster mortality also occurred (April–May 2011 according to the French Shellfish Observatory Network). In the present study, toxins had been detected in oyster tissues since January 2014, while mortalities occurred only in April and May 2014. In agreement with our experimental data, this indicates that oyster intoxication by PSTs alone is not sufficient to induce mortalities, but could rather participate in the induction of oyster mortality in a multifactorial way that involves vibrios and likely other pathogens [13,63].

This study showed that A. catenella increases the susceptibility of C. gigas oysters to pathogenic V. tasmaniensis. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a direct link between a previous exposure of marine invertebrates to a paralytic shellfish toxin (PST) producer and the mortality induced by a pathogenic microorganism has been established. The interaction A. catenella/C. gigas/Vibrio was supported by the co-occurrence of oyster mortality and PST presence in oyster organs. The field observation suggested that A. catenella development in situ could trigger C. gigas mortality. Among the dinoflagellates producing PSTs, the genus Alexandrium is one of the major genera with respect to its diversity, magnitude and consequences on the ecosystem components [24]. Studies will provide further insight into the relationships between the established and emerging toxic dinoflagellates and mass mortalities of marine invertebrates. In particular the role of these algae in predisposing marine animals to microbes (bacteria and/or virus) occurring frequently in the environment should be the subject of further study. Other research focusing on direct interactions between toxins and bacteria would be required to better understand the mechanisms involved in these interactions. To conclude, in addition to complex environmental factors explaining mass mortalities of bivalve mollusks, feeding on toxic algae should now be considered a contributing factor.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Field Survey in Thau Lagoon

4.1.1. Collection of Environmental Samples and Processing

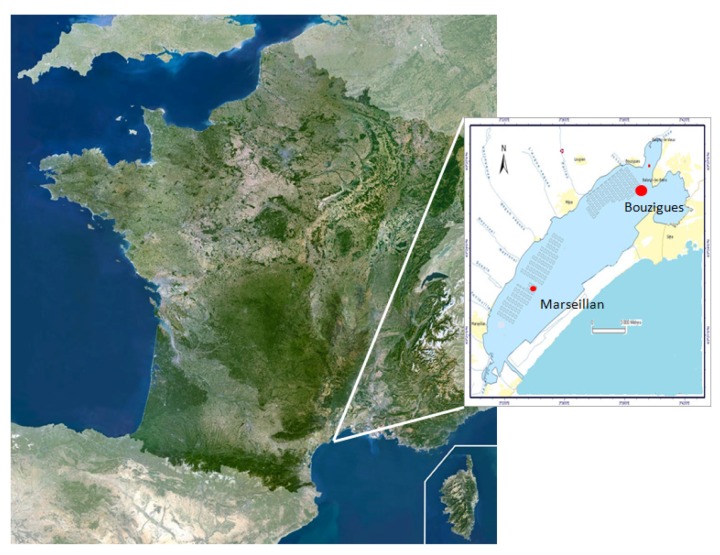

Phytoplankton samples from Thau Lagoon (Languedoc-Roussillon, France) were collected each month from November 2013–June 2014 inside the oyster farm named Bouzigues (N 43°26.058′ and E 003°39.878′) (Figure 4). Sea water (duplicate) was collected from the sub-surface (−50 cm) using a pump. On the boat, 20–30 liters of water were concentrated through 20-μm pore filters to a final volume of 50 mL (fraction >20 μm). Total DNA from 1 mL of this fraction was extracted and purified according to the standard procedure of the current protocols in molecular biology, Unit 2.2.1 [64]. After purification, DNA was conserved in 100 μL of water at −20 °C until PCR was performed.

Figure 4.

Map showing locations of the sampling stations in Thau Lagoon.

4.1.2. Dynamics of Alexandrium catenella

Species belonging to the Alexandrium tamarense complex are often difficult to separate. This complex is composed of three morphospecies, namely A. fundyense (Balech), Alexandrium catenella (Whedon & Kofoid) Balech and A. tamarense (Lebour) Balech. Taxa, such as A. catenella and A. tamarense, are considered as cryptic species [65]. Recently, John et al. [66] proposed to rename A. catenella (Whedon & Kofoid) Balech Alexandrium pacificum (Litaker). However, this proposition is still under debate [67]. In Thau Lagoon, Genovesi et al. [36] showed the simultaneous presence of the toxic A. catenella and the non-toxic A. tamarense [68] that belong to Group IV and Group III, respectively. By microscopic observation, A. catenella cannot be formally identified; molecular identification is therefore the most accurate method to identify this species accurately in a preserved natural samples.

From field-preserved Thau water samples, Alexandrium catenella/tamarense abundance (cells·L−1) was determined using photonic microscopy counting. As specified above, based on the morphological characteristics, it was difficult to discriminate A. catenella from A. tamarense in the field samples. To specifically identify and quantify the presence of A. catenella in water, we performed a quantitative method using the primers FACAT28 and RACATAM269 from Genovesi et al. [36] that target specifically the 18S–28S rRNA ITS region of A. catenella. Briefly, PCR amplifications were performed in the Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). In short, the following components were mixed: 1 μM of each primer (3.33 μM) and 3 μL of reaction mix (Light Cycler® 480 SYBR® Green I Master mix, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in a final volume of 5 μL. DNA (1 μL) was added as the PCR template to the mix, and the following run protocol was used: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 95 °C for 10 s; 58 °C for 10 s; 72 °C for 10 s. A subsequent melting temperature curve was performed between 65 °C and 97 °C with a heating rate of 0.11 °C/s, a continuous fluorescence measurement and a cooling step to 40 °C. Each PCR was performed in duplicate. To determine the qPCR efficiency, the standard curve was generated using five serial dilutions (1:1, 1:3, 1:7, 1:15, 1:31) of a DNA sample of the A. catenella ACT03 strain. Before quantitative PCR analysis, a significant linear relationship (R2 = 0.99) was demonstrated between the cycle threshold (Ct) and the logarithm of the initial concentration of A. catenella ACT03 from 4 to 4000 cells·L−1 (the detection limit). Moreover, the PCR product analysis on agarose gel and by melting curve revealed a unique lane (240 bp) and a unique peak (80 °C), respectively, indicating the formation of a single PCR product with no artifacts (data not shown).

4.1.3. Oyster Mortality

Oyster mortality was monitored in Thau Lagoon from November 2013–June 2014 by the French Shellfish Observatory Network [69]. Oysters were natural diploid Crassostrea gigas juveniles collected in 2012 and 2013 in the basin of Arcachon, France (initial average shell length ≤30 mm,). Oysters were placed inside an oyster farm, called Marseillan East (N 43°36.461′ and E 003°55.394′, Marseillan, Languedoc-Roussillon, France), that corresponds to a representative site of oyster mortalities that occur throughout the lagoon (Figure 4). In fact, mortalities were shown to affect different oyster farms within Thau Lagoon (in Marseillan and Bouzigues) identically in terms of kinetics and magnitude [23].

4.1.4. Oyster Biotoxin Contamination

To monitor contamination by PSTs, juvenile oysters (Batch 2013.2) produced at the Institut Français de Recherche pour l'Exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER) Hatchery in Bouin, France (initial average shell length 30 ± 0.4 mm), were immersed in ThauLagoon at the oyster farm named Bouzygues (N 43°26.058′ and E 003°39.878′) in November 2013 (Figure 4). Five juvenile oysters were randomly collected each month from November 2013–June 2014. Pooled tissues of oysters were frozen at −20 °C until toxin extraction and subsequent analyzes were performed.

4.2. Experimental Infections

4.2.1. Oysters

Oysters used for experimental infections (Batches 2013.2 and 2014.2) were diploid Crassostrea gigas juveniles produced at the IFREMER Hatchery in Bouin, France (initial average shell length 30 ± 0.4 mm).

4.2.2. Algae Production

The experiments were carried out with a toxic strain of Alexandrium catenella (ACT03), a non-PST producing strain, Alexandrium tamarense (ATT07), and the haptophyte, Tisochrysis lutea, which is considered a foraging alga. ACT03 and ATT07 were isolated from Thau Lagoon in 2003 and 2007, respectively. Examination of the morphology of the studied strain ACT03 clearly showed the absence of the ventral pore between the plates 1’ and 4’ and the ability to form chains of up to eight cells during the exponential growth phase. This corresponds to the description of Alexandrium catenella (Whedon & Kof) Balech. In contrast, cells from the ATT07 culture showed clearly the presence of this previously-described ventral pore, and these are always observed in single or paired cells. Analysis of the nuclear rRNA fragment, including ITS1, the 5.8S rRNA gene, ITS2, and the D1/D2 28S rRNA genes revealed that the strain ACT03 belonged to the A. catenella species from Group IV (temperate Asian clade) and that the strain ATT07 belongs to A. tamarense (Group III) [36]. Dinoflagellates were grown at 20 °C under cool-white fluorescent illumination (100 μmoles photons/m2/s) in batch cultures, using a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. The enriched natural sea water (ENSW) culture medium was carried out following Harrison et al. [70] and was characterized by a salinity of 35. For the experiments, algae populations were in their exponential growth phase.

4.2.3. Pathogenic Bacterial Strain

Bacteria for infection were prepared as follows. A colony of Vibrio tasmaniensis LGP32 wild-type previously isolated on a Zobell media Petri dish was grown overnight at 20 °C in liquid medium under agitation (150 rpm). Cells were then washed three times with sterile seawater (SSW) by centrifugation (10 min, 1000 g, 20 °C).

4.2.4. Experimental Design

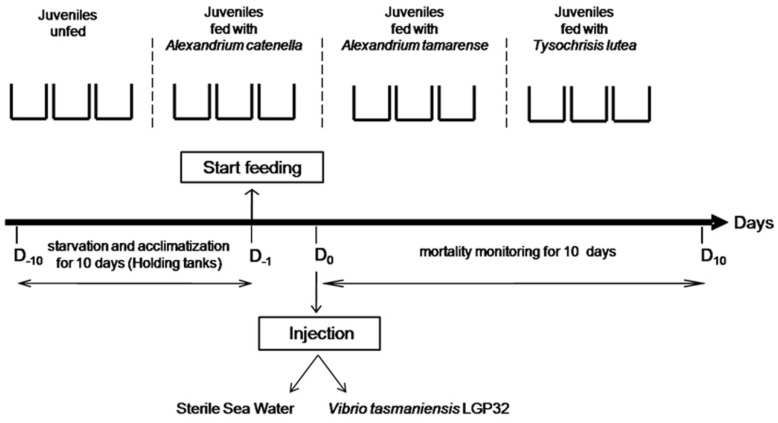

Two independent experimental exposures to Alexandrium catenella were carried out according to the protocol described by Rolland et al. [47]. Briefly, after 10 days of acclimatization without feeding, Crassostrea gigas juveniles were randomly placed into tanks (50 individuals per tank, 3 tanks per condition) containing 6 liters of filtered (0.2 μm) seawater thermo-regulated at 22 °C. Then, oysters were subjected to different treatments, including exposure for 24 h to the toxic A. catenella and the non-toxic Alexandrium tamarense or Tisochrysis lutea at an initial concentration of 2 × 106 cells·L−1, similar to the conditions observed during a natural bloom in Thau Lagoon [38]. Over the experiment, the algae concentration was maintained between 1 × 106 and 3 × 106 cells·L−1 by adding algae to the sea water tanks. In control tanks, no algae were added. After a 24 h exposure, each batch of oysters received a 30% lethal dose (LD30) of bacteria determined at Day 7. For that, each juvenile was injected with one dose of V. tasmaniensis LGP32 (50 μL/animal; 2 × 108 and 1 × 109 for Batches 2013.2 and 2014.2, respectively) into its adductor muscle. Control oysters were injected with 50 μL of sterile seawater (SSW). The mortality of juvenile oysters was monitored daily over 10 days (Figure 5). To determine the level of PST contamination of oysters, dead animals were collected each day for the duration of the experiment. Pooled tissues were frozen at −20 °C until the extraction of the toxin was carried out.

Figure 5.

Laboratory experimental design.

4.3. Neurotoxins Analysis

To extract the PSTs, 5 mL of 0.1 N hydrochloric acid were added, and the samples were mixed with a high-speed homogenizer (15,000 rpm) for 2 min. The pH was adjusted between 2.0 and 4.0, then the samples were centrifuged at 4200 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were filtered on 10-kDa polyethersulfone (PES) filters, and the toxin content was analyzed using the liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection (LC/FD) PSP toxin analyses method of Van De Riet [71]. The toxins GTXs, dc-GTXs, dc-STXs and STXs were separated using a reverse chromatography column (Zorbax Bonus RP, 3.5 μM, 4.6 × 150 mm, Agilent Technologies, Massy, France) with a flow rate of 0.8 mL·min−1. The eluent pH and/or column temperature were optimized to separate dc-GTX3/GTX5/dc-GTX-2 and C1/C2. The toxin concentrations were determined using certified standards provided by CNRC (Halifax, NS, Canada).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

The non-parametric Kaplan-Meier test was used to estimate Wilcoxon and Tarone-Ware values for comparing the experimental survival curves [72]. A confidence limit of 95% was used to test the significance of differences between groups. Data for the same experiment groups were pooled since there were no significant differences (p > 0.05). Values are the mean ± SD from two independent experiments * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Delphine Destoumieux-Garzon for critical reading of the manuscript and to Marc Leroy and Georges Rovillon for technical assistance. This work received financial support from the Ecosphère Continentale et Côtière (EC2CO) Microbien projects (Apotox 2012–2014 and Intervibrio 2013–2015). Thanks to the University of Montpellier (Ecole Doctorale GAIA: Biodiversité, Agriculture, Alimentation, Environnement, Terre, Eau) for funding Celina Abi-Khalil PhD and to IFREMER for the postdoctoral grant held by Carmen Lopez-Joven.

Supplementary Materials

The following figure is available online at www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/8/1/24/s1. Figure S1. Variation of cell concentration in tanks during the experiments. Alexandrium catenella (blue); Alexandrium tamarense (red); Tisochrysis lutea (green).

Author Contributions

M.L. and J.L.R. conceived of and designed the experiments. C.A.K., C.L.J., E.A. and J.L.R. performed the experiments. C.A.K. and J.L.R. analyzed the data. C.A.K., C.L.J., E.A., V.S. and Z.A. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. C.A.K., M.L. and J.L.R. wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sabry R.C., da Silva P.M., Gesteira T.C.V., Pontinha V.D., Magalhaes A.R.M. Pathological study of oysters Crassostrea gigas from culture and C. rhizophorae from natural stock of Santa Catarina Island, SC, Brazil. Aquaculture. 2011;320:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burge C.A., Judah L.R., Conquest L.L., Griffin F.J., Cheney D.P., Suhrbier A., Vadopalas B., Olin P.G., Renault T., Friedman C.S. Summer seed mortality of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas Thunberg grown in Tomales Bay, California, USA: The influence of oyster stock, planting time, pathogens, and environmental stressors. J. Shellfish Res. 2007;26:163–172. doi: 10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26[163:SSMOTP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolas J.L., Ansquer D., Cochard J.C. Isolation and characterization of a pathogenic bacterium specific to Manila clam Tapes-philippinarum larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 1992;14:153–159. doi: 10.3354/dao014153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins C., Hick P., Gabor M., Spiers Z., Fell S.A., Gu X.N., Read A., Go J., Dove M., O’Connor W., et al. Identification and characterisation of an ostreid herpes virus-1 microvariant (OsHV-1 mu-var) in Crassostrea gigas (Pacific oysters) in Australia. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2013;105:109–126. doi: 10.3354/dao02623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keeling S.E., Brosnahan C.L., Williams R., Gias E., Hannah M., Bueno R., McDonald W.L., Johnston C. New Zealand juvenile oyster mortality associated with ostreid herpesvirus 1—An opportunistic longitudinal study. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2014;109:231–239. doi: 10.3354/dao02735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domeneghetti S., Varotto L., Civettini M., Rosani U., Stauder M., Pretto T., Pezzati E., Arcangeli G., Turolla E., Pallavicini A., et al. Mortality occurrence and pathogen detection in Crassostrea gigas and Mytilus galloprovincialis close-growing in shallow waters (Goro lagoon, Italy) Fish Shellfish Immun. 2014;41:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soletchnik P., le Moine O., Faury N., Razet D., Geairon P., Goulletquer P. Summer mortality of the oyster in the Bay Marennes-Oleron: Spatial variability of environment and biology using a geographical information system (GIS) Aquat. Living Resour. 1999;12:131–143. doi: 10.1016/S0990-7440(99)80022-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berthelin C., Kellner K., Mathieu M. Storage metabolism in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) in relation to summer mortalities and reproductive cycle (west coast of France) Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2000;125:359–369. doi: 10.1016/S0305-0491(99)00187-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnier M., Labreuche Y., Garcia C., Robert M., Nicolas J.L. Evidence for the involvement of pathogenic bacteria in summer mortalities of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Microb. Ecol. 2007;53:187–196. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gay M., Renault T., Pons A.M., le Roux F. Two vibrio splendidus related strains collaborate to kill Crassostrea gigas: Taxonomy and host alterations. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2004;62:65–74. doi: 10.3354/dao062065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacoste A., Jalabert F., Malham S., Cueff A., Gelebart F., Cordevant C., Lange M., Poulet S.A. A Vibrio splendidus strain is associated with summer mortality of juvenile oysters Crassostrea gigas in the Bay of Morlaix (North Brittany, France) Dis. Aquat. Org. 2001;46:139–145. doi: 10.3354/dao046139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Roux F., Binesse J., Saulnier D., Mazel D. Construction of a Vibrio splendidus mutant lacking the metalloprotease gene vsm by use of a novel counterselectable suicide vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:777–784. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02147-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemire A., Goudenege D., Versigny T., Petton B., Calteau A., Labreuche Y., le Roux F. Populations, not clones, are the unit of vibrio pathogenesis in naturally infected oysters. ISME J. 2015;9:1523–1531. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duperthuy M., Binesse J., le Roux F., Romestand B., Caro A., Got P., Givaudan A., Mazel D., Bachere E., Destoumieux-Garzon D. The major outer membrane protein OmpU of Vibrio splendidus contributes to host antimicrobial peptide resistance and is required for virulence in the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;12:951–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duperthuy M., Schmitt P., Garzon E., Caro A., Rosa R.D., le Roux F., Lautredou-Audouy N., Got P., Romestand B., de Lorgeril J., et al. Use of OmpU porins for attachment and invasion of Crassostrea gigas immune cells by the oyster pathogen Vibrio splendidus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:2993–2998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015326108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanhove A.S., Duperthuy M., Charriere G.M., le Roux F., Goudenege D., Gourbal B., Kieffer-Jaquinod S., Coute Y., Wai S.N., Destoumieux-Garzon D. Outer membrane vesicles are vehicles for the delivery of Vibrio tasmaniensis virulence factors to oyster immune cells. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;17:1152–1165. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segarra A., Pepin J.F., Arzul I., Morga B., Faury N., Renault T. Detection and description of a particular Ostreid herpesvirus 1 genotype associated with massive mortality outbreaks of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, in France in 2008. Virus Res. 2010;153:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martenot C., Oden E., Travaille E., Malas J.P., Houssin M. Detection of different variants of Ostreid Herpesvirus 1 in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas between 2008 and 2010. Virus Res. 2011;160:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia C., Thebault A., Degremont L., Arzul I., Miossec L., Robert M., Chollet B., Francois C., Joly J.P., Ferrand S., et al. Ostreid herpes virus1 detection and relationship with Crassostrea gigas spat mortality in France between 1998 and 2006. Vet. Res. 2011;42:416–417. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samain J.F. Review and perspectives of physiological mechanisms underlying genetically-based resistance of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas to summer mortality. Aquat. Living Resour. 2011;24:227–236. doi: 10.1051/alr/2011144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jolivel A., Elodie F. Statistical Analysisof Oystermortalitydata Acquired by the National Observatory shellfish. [(accessed on 3 December 2015)]. Available online: http://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00130/24095/

- 22.Pernet F., Barret J., le Gall P., Corporeau C., Degremont L., Lagarde F., Pepin J.F., Keck N. Mass mortalities of Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas reflect infectious diseases and vary with farming practices in the Mediterranean Thau lagoon, France. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2012;2:215–237. doi: 10.3354/aei00041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pernet F., Lagarde F., Jeannee N., Daigle G., Barret J., le Gall P., Quere C., D’orbcastel E.R. Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Mass Mortalities in Oysters Is Influenced by Energetic Reserves and Food Quality. PLoS ONE. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson D.M., Alpermann T.J., Cembella A.D., Collos Y., Masseret E., Montresor M. The globally distributed genus Alexandrium: Multifaceted roles in marine ecosystems and impacts on human health. Harmful Algae. 2012;14:10–35. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scholin C.A., Herzog M., Sogin M., Anderson D.M. Identification of group- and strain-specific genetic markers for globally distributed Alexandrium (Diniphyceae). Sequence analysis of LSU rRNA gene. J. Phycol. 1994;30:744–754. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1994.00744.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cόrdova J.L., Müller I. Use of PCR and partial sequencing of the large-subunit rRNA gene to indentify Alexandrium catenella (Dinophycea) from the South of Chile. Harmful Algae. 2002;1:343–350. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9883(02)00066-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKenzie L., de Salas M., Adamson J., Beuzenberg V. The dinoflagellate genus Alexandrium (Halim) in New Zealand coastal waters: Comparative morphology, toxicity and molecular genetics. Harmful Algae. 2004;3:71–92. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2003.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adachi M., Sako Y., Ishida Y. Analyses of Alexandrium (Dinophyceae) species using sequences of the 5.8S ribosomal DNA and internal transcribed spacer regions. J. Phycol. 1996;32:424–432. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1996.00424.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeung P.K.K., Wong F.T.W., Wong J.T.Y. Large subunit rDNA sequences from Alexandrium catenevilalla strains isolated during algal blooms in Hong Kong. J. Appl. Phycol. 2002;14:147–150. doi: 10.1023/A:1019552100625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vila M., Garces E., Maso M., Camp J. Is the distribution of the toxic dinoflagellates Alexandrium catenella expanding along the NW Mediterranean coast? Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001;23:497–514. doi: 10.3354/meps222073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penna A., Garcés E., Vila M., Giacobbe M.G., Fraga S., Luglie A., Bravo I., Bertozzini E., Vernesi C. Alexandrium catenella (Dinophycea), a toxic ribotype expanding in the NW Mediterranean sea. Mar. Biol. 2005;148:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s00227-005-0067-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garces E., Maso M., Camp J.A. Recurrent and localized dinoflagellate bloom in a Mediterranean beach. J. Plankton Res. 1999;21:2373–2391. doi: 10.1093/plankt/21.12.2373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bravo I., Vila M., Maso M., Figueroa R.I., Ramilo I. Alexandrium catenella and Alexandrium minutum blooms in the Mediterranean Sea: Toward the identification of ecological niches. Harmful Algae. 2008;7:515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2007.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abadie E., Amzil Z., Belin C., Comps M.A., Elzière-Papayanni P., Lassus P., le Bec C., Baut C.M.-L., Nezan E., Poggi R. Contamination de l’étang de Thau par Alexandrium tamarense. [(accessed on 3 December 2015)]. Available online: http://www.ifremer.fr/docelec/doc/1999/rapport-884.pdf.

- 35.Lilly E.L., Kulis D.M., Gentien P., Anderson D.M. Paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins in France linked to a human-introduced strain of Alexandrium catenella from the western Pacific: Evidence from DNA and toxin analysis. J. Plankton Res. 2002;24:443–452. doi: 10.1093/plankt/24.5.443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Genovesi B., Shin-Grzebyk M.S., Grzebyk D., Laabir M., Gagnaire P.A., Vaquer A., Pastoureaud A., Lasserre B., Collos Y., Berrebi P., et al. Assessment of cryptic species diversity within blooms and cyst bank of the Alexandrium tamarense complex (Dinophyceae) in a Mediterranean lagoon facilitated by semi-multiplex PCR. J. Plankton Res. 2011;33:405–414. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbq127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laabir M., Amzil Z., Lassus P., Masseret E., Tapilatu Y., de Vargas R., Grzebyk D. Viability, growth and toxicity of Alexandrium catenella and Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) following ingestion and gut passage in the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Aquat. Living Resour. 2007;20:51–57. doi: 10.1051/alr:2007015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laabir M., Jauzein C., Genovesi B., Masseret E., Grzebyk D., Cecchi P., Vaquer A., Perrin Y., Colos Y. Influence of temperature, salinity and irradiance on the growth and cell yield of the harmful red tide dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella colonizing Mediterranean waters. J. Plankton Res. 2011;33:1550–1563. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbr050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masselin P., Amzil Z., Abadie E., Nézan E., le Bec C., Chiantella C., Truquet P. Paralytic shellfish poisoning on the French Mediterranean coast in the autumn 1998: Alexandrium tamarense complex (Dinophyceae) as causative agent. In: Hallegraeff G.M., Blackburn S.I., Bolch C.J., Lewis R.J., editors. Harmful Algae Blooms. JOC-UNESCO; Paris, France: 2000. pp. 407–441. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Twarog B.M., Hidaka T., Yamaguchi H. Resistance to totrodoxin and saxitoxin in nerves of bivalves mollusks: A possible correlation with paralytic shellfish poisoning. Toxicon. 1972;10:273–278. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(72)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shumway S.E., Cucci T.L. The effects of the toxic dinoflagellate Protogonyaulax tamarensis on the feeding and behavior of bivalve molluscs. Aquat. Toxicol. 1987;10:9–27. doi: 10.1016/0166-445X(87)90024-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shumway S.E. A review of the effects of algal blooms on shellfish and aquaculture. J. World. Aquac. Soc. 1990;21:65–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-7345.1990.tb00529.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bricelj V.M., Connell L., Konoki K., MacQuarrie S.P., Scheuer T., Catterall W.A., Trainer V.L. Sodium channel mutation leading to saxitoxin resistance in clams increases risk of PSP. Nature. 2005;434:763–767. doi: 10.1038/nature03415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bardouil M., Bohec M., Cormerais M., Bougrier S., Lassus P. Experimental study of the effects of a toxic microalgal diet on feeding of the oyster Crassostrea gigas Thunberg. J. Shellfish Res. 1993;1:417–422. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wildish D., Lassus P., Martin J., Saulnier A., Bardouil M. Effect of the PSP-causing dinoflagellate, Alexandrium sp. on the initial feeding response of Crassostrea gigas. Aquat. Living Resour. 1998;11:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0990-7440(99)80029-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lassus P., Baron R., Garen P., Truquet P., Masselin P., Bardouil M., Leguay D., Amzil Z. Paralytic shellfish poison outbreaks in the Penze estuary: Environmental factors affecting toxin uptake in the oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Aquat. Living Resour. 2004;17:207–214. doi: 10.1051/alr:2004012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rolland J.L., Pelletier K., Masseret E., Rieuvilleneuve F., Savar V., Santini A., Amzil Z., Laabir M. Paralytic toxins accumulation and tissue Expression of α-amylase and lipase genes in the pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas fed with the neurotoxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:2519–2534. doi: 10.3390/md10112519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gueguen M., Bardouil M., Baron R., Lassus P., Truquet P., Massardier J., Amzil Z. Detoxification of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas fed on diets of Skeletonema costatum with and without silt, following PSP contamination by Alexandrium minutum. Aquat. Living Resour. 2008;21:13–20. doi: 10.1051/alr:2008010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medhioub W., Lassus P., Truquet P., Bardouil M., Amzil Z., Séchet V., Sibat M., Soudant P. Physiological responses of Crassostrea gigas when exposed to the toxic dinoflagellates Alexandrium ostenfeldii: Toxin uptake and detoxification. Aquaculture. 2012;358:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2012.06.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegaret H., Wikfors G.H., Soudant P., Lambert C., Shumway S.E., Berard J.B., Lassus P. Toxic dinoflagellates (Alexandrium fundyense and A. catenella) have minimal apparent effect on oyster hemocytes. Mar. Biol. 2007;152:441–447. doi: 10.1007/s00227-007-0703-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hegaret H., da Silva P.M., Wikfors G.H., Haberkorn H., Shumway S.E., Soudant P. In vitro interactions between several species of harmful algae and haemocytes of bivalve mollusks. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2011;27:249–266. doi: 10.1007/s10565-011-9186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mello D.F., da Silva P.M., Barracco M.A., Soudant P., Hegaret H. Effects of the dinoflagellates Alexandrium minutum and its toxin (saxitoxin) on the functional activity and gene expression of Crassostrea gigas hemocytes. Harmful Algae. 2013;26:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2013.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medhioub W., Ramondenc S., Vanhove A., Vergnes A., Masseret E., Savar V., Amzil Z., Laabir M., Rolland J.L. Exposure to the Neurotoxic Dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella induces apoptosis of the oyster Crassostrea gigas hemocytes. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:4799–4814. doi: 10.3390/md11124799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lassudrie M., Soudant P., Nicolas J.L., Fabioux C., Lambert C., Miner P., le Grand J., Petton B., Hegaret H. Interaction between toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium catenella exposure and disease associated with herpesvirus OsHV-1 mu Var in Pacific oyster spat Crassostrea gigas. Harmful Algae. 2015;45:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2015.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bachere E., Rosa R.D., Schmitt P., Poirier A.C., Merou N., Charriere G.M., Destoumieux-Garzon D. The new insights into the oyster antimicrobial defense: Cellular, molecular and genetic view. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2015;46:50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang L., Li L., Guo X., Litman G.W., Dishaw L.J., Zhang G. Massive expansion and functional divergence of innate immune genes in a protostome. Sci. Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1038/srep08693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fistarol G.O., Legrand C., Selander E., Hummert C., Stolte W., Graneli E. Allelopathy in Alexandrium spp.: Effect on a natural plankton community and on algal monocultures. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2004;35:45–56. doi: 10.3354/ame035045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oshima Y. Chemical and enzymatic transformation of paralytic shellfish toxins in marine organisms. In: Lassus P., Arzul G., Erard E., Gentien P., Marcaillou C., editors. Harmful Marine Algal Blooms. Lavoisier/Intercept; Paris, France: 1995. pp. 475–480. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki T., Ichimi K., Oshima Y., Kamiyama T. Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) toxin profiles and short-term detoxification kinetics in mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis fed with the toxic dinoflagellate Alexandrium tamarense. Harmful Algae. 2003;2:201–206. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9883(03)00042-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bougrier S., Lassus P., Bardouil M., Masselin P., Truquet P. Paralytic shellfish poison accumulation yields and feeding time activity in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and king scallop (Pecten maximus) Aquat. Living Resour. 2003;16:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S0990-7440(03)00080-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cembella A.D., Shumway S.E., Larocque R. Sequestering and putative biotransformation of paralytic shellfish toxins by the sea scallop Placopecten magellanicus: Seasonal and special scales in natural populations. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2005;180:1–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(94)90075-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rolland J.L., Medhioub W., Vergnes A., Abi-khalil C., Savar V., Abadie E., Masseret E., Amzil Z., Laabir M. A feedback mechanism to control apoptosis occurs in the digestive gland of the oyster Crassostrea gigas exposed to the paralytic shellfish toxins producer Alexandrium catenella. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:5035–5054. doi: 10.3390/md12095035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petton B., Bruto M., James A., Labreuche Y., Alunno-Bruscia M., le Roux F. Crassostrea gigas mortality in France: The usual suspect, a herpes virus, may not be the killer in this polymicrobial opportunistic disease. Front. Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ausubel F.M., Brent R., Kingston R.E., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Struhl K. Current Protocol in Molecular Biology. Volume 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2003. Preparation of genomic DNA from mammalian tissue; pp. 2.2.1–2.2.3. [Google Scholar]

- 65.John U., Fensome R.A., Medlin L.K. The application of a molecular clock based on molecular sequences and the fossil record to explain biogeographic distributions within the Alexandrium tamarense “species complex” (Dinophyceae) Mol. Biolog. Evol. 2003;20:1015–1027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.John U., Litaker W., Montresor M., Murray S., Brosnahan M.L., Anderson D.M. Proposal to reject the name Gonyaulux catenella (Alexandrium catenella) (Dinophyceae) Taxon. 2014;63:932–933. doi: 10.12705/634.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang L., Zhuang Y., Zhang H., Lin X., Lin S. DNA barcoding species in Alexandrium tamarense complex using ITS and proposing designation of five species. Harmful Algae. 2014;31:100–113. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lilly E.L., Halanych K.M., Anderson D.M. Species boundaries and global biogeography of the Alexandrium tamarense complex (Dinophyceae) J. Phycol. 2007;43:1329–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00420.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shellfish Observatory Network (RESCO) Ifremer, 155 rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 92138, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France. [(accessed on 3 December 2015)]. Available online: http://wwz.ifremer.fr/observatoire_conchylicole.

- 70.Harrison P.J., Waters R.E., Taylor F.J.R. A broad-spectrum artificial seawater medium for coastal and open ocean phytoplankton. J. Phycol. 1980;16:28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1980.tb00724.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van de Riet J., Gibbs R.S., Muggah P.M., Rourke W.A., MacNeil J.D., Quilliam M.A. Liquid Chromatography Post-Column Oxidation (PCOX) Method for the Determination of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in Mussels, Clams, Oysters, and Scallops: Collaborative Study. J. AOAC Int. 2011;94:1154–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaplan E.L., Meier P. Non parametric estimation for incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.