Abstract

Shewanella species are facultative anaerobic bacteria that colonize redox-stratified habitats where O2 and nutrient concentrations fluctuate. The model species Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 possesses genes coding for three terminal oxidases that can perform O2 respiration: a bd-type quinol oxidase and cytochrome c oxidases of the cbb3-type and the A-type. Whereas the bd- and cbb3-type oxidases are routinely detected, evidence for the expression of the A-type enzyme has so far been lacking. Here, we investigated the effect of nutrient starvation on the expression of these terminal oxidases under different O2 tensions. Our results reveal that the bd-type oxidase plays a significant role under nutrient starvation in aerobic conditions. The expression of the cbb3-type oxidase is also modulated by the nutrient composition of the medium and increases especially under iron-deficiency in exponentially growing cells. Most importantly, under conditions of carbon depletion, high O2 and stationary-growth, we report for the first time the expression of the A-type oxidase in S. oneidensis, indicating that this terminal oxidase is not functionally lost. The physiological role of the A-type oxidase in energy conservation and in the adaptation of S. oneidensis to redox-stratified environments is discussed.

Members of the genus Shewanella constitute a physiologically and ecologically diverse group of facultative anaerobic bacteria which are widely distributed in aquatic and sedimentary systems1,2. A remarkable respiratory versatility allowing the use of a wide variety of electron acceptors combined with a complex chemotaxis system to locate the most favorable conditions for growth represent formidable assets for Shewanella species to colonize stratified environments2,3,4. While anaerobic respiration in Shewanella has received considerable attention given the biotechnological potential for the bioremediation of various environmental pollutants1, only a few studies have focused on aerobic respiration. Yet, in habitats that span from anaerobic to highly aerobic conditions, adaptation to differences in temporal and spatial O2 concentrations is clearly key to the ecological success of the Shewanella species and underscores the importance of understanding the mechanisms involved.

During aerobic respiration, terminal oxidases couple the oxidation of a quinol or a c-type cytochrome to the reduction of O2, producing water. In prokaryotes, terminal oxidases are grouped in two major families: the bd-type oxidases and the heme-copper oxidases (HCOs). Cytochrome bd-type oxidases use quinol as electron donor, function bioenergetically less efficiently than HCOs and are generally induced under O2-limited conditions and/or a wide variety of stress conditions5,6. HCOs are divided into three subfamilies: the A subfamily including mitochondrial-like terminal oxidases (aa3-type), the B subfamily comprising terminal oxidases from extremophilic prokaryotes (ba3-type oxidases) and the cbb3-type oxidases of the C subfamily7,8. Contrary to the eukaryotic (mammalian) respiratory system where electrons are transferred to a single terminal oxidase, most bacteria possess multiple terminal oxidases that differ in proton pumping efficiency and O2 affinity, enabling energy production under various O2 tensions9. A-type oxidases have a low affinity for O2 with a proton-pumping stoichiometry of 1 H+ /e−, whereas cbb3-type oxidases are generally considered to have a high affinity for O2 but with a lower H+/e− ratio of 0.510,11. Consequently, A-type oxidases are more efficient at transducing energy than cbb3-type oxidases and are the major terminal oxidases expressed under aerobic conditions. In those bacteria that possess both an A-type and a cbb3-type oxidase, the former is expressed to support growth when O2 is abundant while the latter provides the capacity to respire traces of O2 in microaerobic conditions12. The genome of the model species Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 encodes three terminal oxidases: a bd-type quinol oxidase and two HCOs, a cbb3-type oxidase and an A-type cytochrome c oxidase (Cox)13,14. In a previous study on the multiple respiratory systems of S. oneidensis MR-1, it was proposed that the cbb3-type and Cox are expressed under low and high O2 tensions, respectively, whereas the bd-type oxidase would be required for growth under microaerobic conditions and/or stressful conditions15. Subsequently it was indeed reported that, while weakly expressed in aerobic conditions, the bd-type oxidase conferred resistance to nitrite in S. oneidensis16. Concerning the HCOs in S. oneidensis, however, genetic and biochemical analysis indicated that under both microaerobic and aerobic conditions only the cbb3-type oxidase was expressed14,17. Thus, the cbb3-type oxidase was the predominant oxidase under aerobic conditions while, unexpectedly, the Cox oxidase had no physiological significance under the tested conditions. In view of these results it was proposed that in the course of evolution the Cox was functionally lost17. Nevertheless, this hypothesis is refuted by the facts that (i) the entire cox gene cluster is conserved in the S. oneidensis genome, and that (ii) the Cox amino acid sequence is highly conserved as compared to phylogenetically related bacteria14. Up to now, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the only bacterium that exhibits a HCO expression pattern similar to S. oneidensis. Indeed, the expression level of the genes encoding an A-type oxidase is kept low under high O2 tensions whereas the genes encoding the cbb3-1 oxidase are highly expressed under the same conditions18. Interestingly, the promoter of the A-type oxidase was found to be induced under nitrogen-, iron- and carbon starvation18,19.

In this study, we surmised that Cox could also be expressed under certain specific conditions. To verify this notion, the expression patterns of the terminal oxidases in S. oneidensis were investigated under nutrient-starved conditions and under different dissolved O2 tensions. In addition to the notable modulation of the expression of the bd-type and cbb3-type oxidases, Cox was detected in cells grown to stationary phase under carbon depletion and highly aerobic conditions. The present results constitute the first report of the expression of the A-type oxidase in S. oneidensis. The physiological role of Cox in the energy conservation and adaptation of S. oneidensis to stratified environments will be evaluated in the discussion section.

Results

Growth parameters of S. oneidensis MR-1 in rich, minimum or nutrient-depleted medium

To determine the physiological significance of the different O2 reductases under nutrient-starved conditions, S. oneidensis was grown aerobically in either rich medium (LB), minimal medium (MM3), carbon-depleted medium (MM3C−; MM3 without sodium DL-lactate) or an iron-depleted medium (MM3I−; MM3 without FeCl2) (see Methods section for details). The wild-type strain was characterized by measuring the growth parameters (Table 1). As expected, maximum growth rate and yield were reached when the strain was grown in LB medium. Under carbon starvation, doubling time increased twofold and the cell density at the stationary phase was threefold lower as compared to minimal medium. The effect of iron depletion on growth was however less pronounced, with a twofold lower growth yield and a doubling time only slightly decreased relative to growth in minimal medium.

Table 1. Growth parameters of S. oneidensis cultivated in different media under aerobic conditions.

| Medium | Doubling timea | Relative yieldb |

|---|---|---|

| MM3 | 114 +/− 6 | 1.00 |

| MM3C− | 237 +/− 12 | 0.34 |

| MM3I− | 137 +/− 7 | 0.50 |

| LB | 54 +/− 1 | 11.36 |

aExpressed in min (mean +/− standard deviation).

bRelative yield is defined as the highest optical density at 600 nm in early stationary phase in the different cultures relative to that of the wild-type strain culture in MM3 medium. The standard deviation is less than 3%.

Data were obtained from at least three separated experiments.

Cytochrome c oxidase activity in solubilised membranes of S. oneidensis

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was determined in solubilised membranes of the S. oneidensis MR-1 wild-type strain and the SLL01 mutant strain, which lacks the cbb3 oxidase. Cells were grown under aerobic (~95 μM O2) or highly aerobic (~165 μM O2) conditions, in rich, minimal or depleted-medium. O2 consumption was monitored with a Clark-type electrode using N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD), an artificial electron donor capable of reducing cytochrome c (Table 2). We previously demonstrated that TMPD is not oxidized by the bd-type oxidase in S. oneidensis14. Accordingly, TMPD oxidase activity only corresponds to the activity of the cbb3-type and A-type cytochrome c oxidases.

Table 2. TMPD oxidase activity in solubilised membranes of S. oneidensis MR-1 and the cbb 3 oxidase deletion strain (SLL01) under different O2 and nutrient conditions.

| Strain | Medium | Growth phasea | Aerobic conditions | Highly aerobic conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. oneidensis Wild type | LB | E | 90 +/− 6 | 88 +/− 6 |

| S | 95 +/− 6 | 88 +/− 3 | ||

| MM3 | E | 52 +/− 1 | 42 +/− 1 | |

| S | 56 +/− 3 | 33 +/− 1 | ||

| MM3I− | E | 148 +/− 14 | 132 +/− 8 | |

| S | 55 +/− 1 | 76 +/− 5 | ||

| MM3C− | E | 77 +/− 5 | 82 +/− 2 | |

| S | 158 +/− 12 | 106 +/− 9 | ||

| S. oneidensis SLL01 | LB | E | 0 | 0 |

| S | 0 | 0 | ||

| MM3 | E | 0 | 0 | |

| S | 0 | 0 | ||

| MM3I− | E | 0 | 0 | |

| S | 0 | 0 | ||

| MM3C− | E | 0 | 0 | |

| S | 21 +/− 1 | 21 +/− 1 |

aExponential (E) or stationary (S) phase of growth.

Activities are expressed in nmol O2.min−1.mg protein−1.

Listed values are averages of at least three separate experiments (mean +/− standard deviation).

In the wild-type strain grown on rich medium (LB), TMPD oxidase activity was constant regardless of growth phase and O2 tension. During growth on minimal medium (MM3), TMPD oxidase activities were slightly lower in highly aerobic conditions than in aerobic conditions. Measured values for MM3 were approximately half those of rich medium. TMPD oxidase activities were higher under conditions of nutrient deficiency than in minimal medium, with significant differences depending on the nature of the starvation. While the activity under iron starvation (MM3I−) was 2–3 times higher during exponential phase compared to stationary phase, the opposite pattern was observed under carbon starvation (MM3C−), where TMPD oxidase activity was significantly higher during stationary phase than during exponential phase. Although no distinction is made at this point between the activities of the A-type and the cbb3-type terminal oxidases, these data highlight that cytochrome c oxidase activity is not only influenced by O2 tension and growth phase but also by the availability of carbon and iron in S. oneidensis.

In the cbb3 deletion mutant SLL01, TMPD oxidase activity was only detected under carbon deficiency and during stationary phase, at both aerobic and highly aerobic conditions. Since TMPD oxidase activity can only arise from the A-type oxidase in SLL01, this result directly shows that Cox is not functionally lost but can be expressed under specific culture conditions. In addition, similar variations were observed when cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured spectrophotometrically via the oxidation of reduced horse heart cytochrome c (data not shown).

Detection of a-type hemes by spectroscopic and HPLC analyses

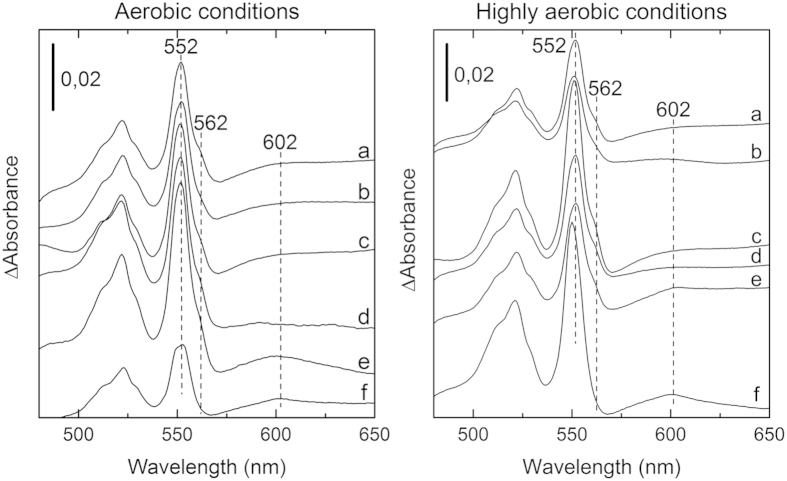

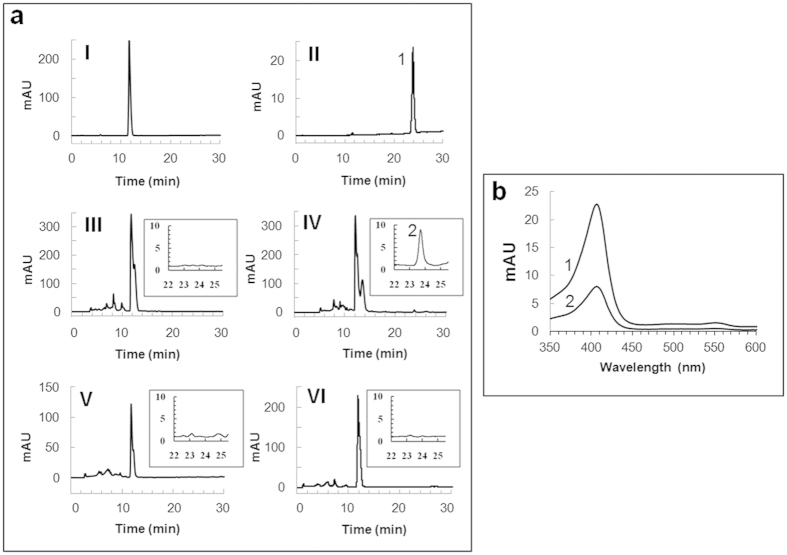

Since the Cox of S. oneidensis has so far not been characterized, the nature of its heme cofactors remained unknown. Nonetheless, the conservation of an arginine residue known to interact with the formyl group of heme a in aa3-type oxidases, and the presence of genes involved in heme a synthesis within the cox gene cluster suggest that subunit I of Cox contains a-type hemes14. Heme a is found as prosthetic group in only one class of proteins, namely the cytochrome a-containing respiratory oxidases in aerobic organisms20. Since heme a absorbs in the 600 nm-region, solubilised membranes from the S. oneidensis wild type and SLL01 cbb3-deletion mutant strains were analyzed by absorption spectroscopy in stationary phase cells (Fig. 1; also includes exponential WT cells in MM3C−) and also in exponentially growing cells (Fig. S1). Spectra show the presence of cytochrome c with peaks around 552 nm and cytochrome b with characteristic shoulders around 562 nm. These signals derive from several different cytochrome c and b proteins present in the membrane. In the SLL01 Δcbb3 mutant, a spectral signal for heme a was detected at 602 nm in membranes from stationary-phase cells grown in carbon-depleted medium, under both aerobic and highly aerobic conditions (Fig. 1f). This observation is consistent with the TMPD oxidase activity that was measured in the same conditions and which can only arise from Cox (Table 2). In the wild-type strain, heme a was only clearly detected in membranes from cells grown to stationary phase under carbon starvation and highly aerobic conditions (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). An unclearly defined putative peak at 602 nm under aerobic conditions in MM3C− was observed that might be proposed to belong to heme a (Fig. 1e), which prompted us to further assess the presence of hemes in the membranes of S. oneidensis MR-1 by HPLC analysis (Fig. 2). In all culture conditions, a major elution peak was detected at around 12 min that corresponds to heme b as judged by the retention time (Fig. 2a) and absorption spectrum (data not shown) of hemin. An additional small peak eluting at around 24 min was identified only with hemes extracted from membranes of stationary-phase cells cultivated under carbon-depleted and highly aerobic conditions (Fig. 2a, IV). This peak was identified as heme a, since heme a extracted from the aa3-type oxidase from bovine heart exhibited an identical retention time (Fig. 2a, II) and similar spectral characteristics with an absorbance peak at 407 nm (Fig. 2b).

Figure 1. Reduced minus oxidized difference absorbance spectra of solubilised membranes from S. oneidensis wild-type and the cbb3 oxidase deletion strain (SLL01) grown under different O2 and nutrient conditions.

The spectra were recorded at room temperature in the presence of 50 μM KCN. Membranes were oxidized with potassium ferricyanide and reduced with sodium ascorbate. The concentration of proteins was 6.0 mg.mL−1. The vertical bars indicate the absorption scale. (a) wild type in LB at stationary phase. (b) wild type in minimal medium (MM3) at stationary phase. (c) wild type in iron-depleted medium (MM3I−) at stationary phase. (d) wild type in carbon-depleted medium (MM3C−) at exponential phase. (e) wild type in carbon-depleted medium (MM3C−) at stationary phase. (f) SLL01 strain in carbon-depleted medium (MM3C−) at stationary phase.

Figure 2. HPLC analysis of non-covalently bound hemes extracted from membranes of S. oneidensis grown under different O2 and nutrient conditions.

(a) Heme analysis by reversed-phase HPLC and detection at 405 nm. Hemes were extracted from 10 mg of membranes of S. oneidensis grown under different culture conditions: highly aerobic conditions and carbon starvation at the exponential (III) and the stationary (IV) phases; highly aerobic conditions and iron starvation at the stationary phase (V); aerobic conditions and carbon starvation at the stationary phase (VI). Hemes were identified by comparison with the retention times of hemin (I) and heme a extracted from the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase from bovine heart (II). Retention times for hemin and heme a were 11.7 and 23.9 min, respectively. Insets are zoom-ins of the chromatograms between 22 and 25.5 min. (b) Absorption spectra (photo-diode array) of peaks 1 and 2 from panels II and IV, respectively.

Overall, spectroscopic data and HPLC analysis together suggest that Cox contains heme a and is only expressed during the stationary phase under carbon-depleted and highly aerobic conditions in S. oneidensis.

Identification of Cox by mass spectrometry

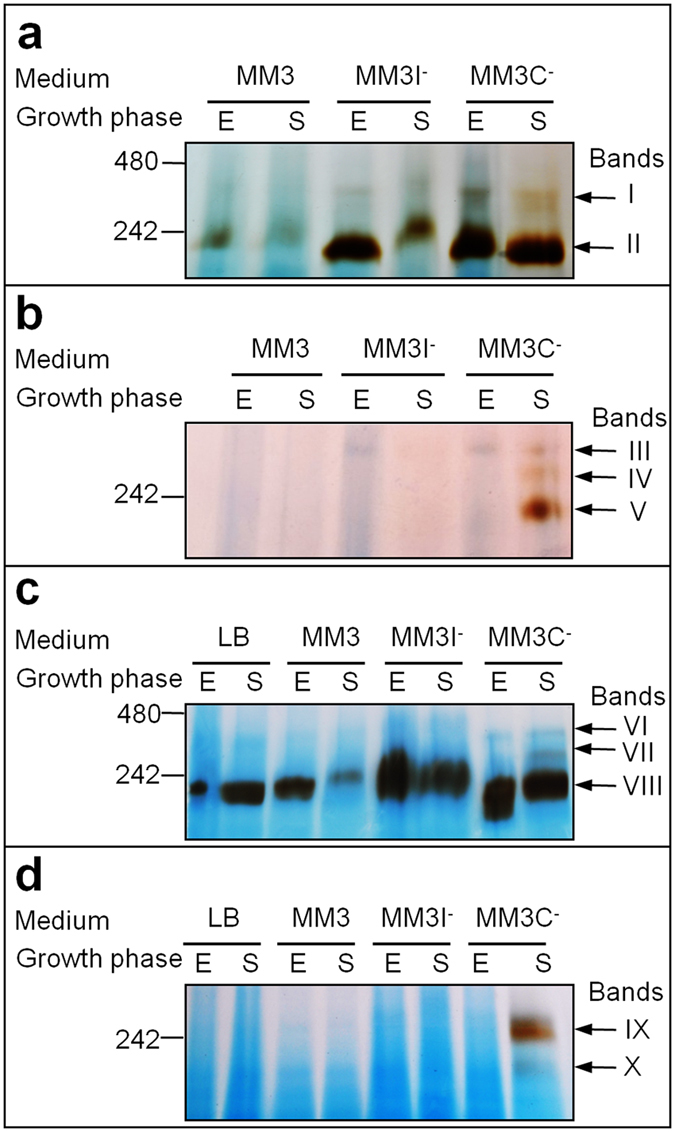

To identify the cytochrome c oxidase(s) responsible for the detected TMPD oxidase activity (Table 2), membrane proteins from S. oneidensis strains MR-1 and SLL01 were separated via Blue Native gel electrophoresis followed by in-gel detection of cytochrome c oxidase activity (Fig. 3). Bands showing activity were cut out from the gel and the proteins digested by trypsin and identified by ESI-Q-ToF mass spectrometry (Table 3 for MM3C− medium and Table S1 for other culture media).

Figure 3. In-gel detection of cytochrome c oxidase activity in BN-gels run with solubilised membranes of S. oneidensis.

Membrane proteins were prepared from S. oneidensis wild-type (a,c) and strain SLL01 lacking the cbb3-type oxidase (b,d) grown in aerobic (a,b) or highly aerobic (c,d) conditions. The S. oneidensis strains were grown on rich medium (LB), minimal medium (MM3), iron-depleted medium (MM3I−) or carbon-depleted medium (MM3C−), and cells were harvested during the exponential (E) or stationary (S) phase of growth. Total proteins (130 μg) were loaded on a 5–15% polyacrylamide gel. Bands of activity are indicated by roman numerals. Molecular mass markers are indicated in kDa.

Table 3. Identification of the cytochrome c oxidases by ESI-Q-ToF mass spectrometry in solubilised membranes of S. oneidensis MR-1 and the cbb 3 oxidase deletion strain (SLL01) grown under carbon-depleted conditions (MM3C−).

| O2 condition | Strain | Growth phasea | Bandb | Protein namec | NCBI enter | Gene | Peptd | Cove |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic conditions | S. oneidensis Wild type | E | I | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | ||||

| II | cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24348335 | ccoO | 23 | 47 | |||

| cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. III | 24373908 | ccoP | 11 | 40 | ||||

| S | I | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | ||||||

| II | cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24348335 | ccoO | 17 | 39 | |||

| cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. III | 24373908 | ccoP | 27 | 65 | ||||

| S. oneidensis SLL01 | E | III | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | |||||

| S | III | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | ||||||

| IV | A-type cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24376079 | coxB | 17 | 38 | |||

| V | A-type cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24376079 | coxB | 8 | 22 | |||

| Highly aerobic conditions | S. oneidensis Wild type | E | VI | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | ||||

| VIII | cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24348335 | ccoO | 26 | 53 | |||

| cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. III | 24373908 | ccoP | 13 | 58 | ||||

| S | VI | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | ||||||

| VII | cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24348335 | ccoO | 17 | 35 | |||

| A-type cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24376079 | coxB | 11 | 25 | ||||

| VIII | cbb3 cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24348335 | ccoO | 25 | 54 | |||

| A-type cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24376079 | coxB | 8 | 15 | ||||

| S. oneidensis SLL01 | S | IX | A-type cyt c oxidase sub. II | 24376079 | coxB | 12 | 22 | |

| X | No cytochrome c oxidase detected | |||||||

aExponential (E) or stationary (S) phase of growth.

bRoman numerals refer to the protein bands from the BN gel shown in Fig. 3.

cProtein name in NCBI database. Cyt: cytochrome. Sub.: subunit.

dNumber of peptides detected.

eProtein sequence coverage by the matching peptides (%).

These results are representative of three similar experiments.

Previously, we reported that the cbb3-type oxidase was the only cytochrome c oxidase present in the S. oneidensis wild-type strain grown in rich medium under aerobic conditions, and that the A-type cytochrome c oxidase was not present in the SLL01 strain under these conditions, despite the lack of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase14. Using membranes from stationary SLL01 cells grown in rich, minimal or iron-depleted media, irrespective of the O2 tension, at only one molecular weight position on the gel were very faint activity bands revealed (Fig. 3b, position of band III). No cytochrome c oxidase peptides were identified in these bands by mass spectrometry (data not shown). At the same position, an activity band was observed in membranes from SLL01 cells growing exponentially under carbon-depleted and aerobic conditions (Fig. 3b, band III), but no cytochrome c oxidase was identified in this band either (Table 3). Additional bands were only observed in membranes of stationary SLL01 cells grown in carbon-depleted medium under aerobic (Fig. 3b, bands IV and V) and highly aerobic conditions (Fig. 3d, bands IX and X). Whereas in band X no cytochrome c oxidase was detected, bands IV, V and IX were found to contain CoxB, the subunit II of Cox (Table 3). Furthermore, CoxB was also identified in SLL01 membranes when the strain was grown to stationary phase in MM3C− under microaerobic conditions (Fig. S2). In line with the presence of Cox in the mutant SLL01, TMPD oxidase activity was detected in the membranes of the bacterium in this condition (Fig. S2).

Using membranes of the wild-type strain cultivated in aerobic conditions, either one or two activity bands were revealed regardless of the culture medium and the growth phase (Fig. 3a, bands I and II). Whereas no cytochrome c oxidase was detected by mass spectrometry in band I, subunits II and III of the cbb3-type oxidase were identified in band II, the major activity band (Table 3 and Table S1). Nevertheless, mass spectrometry analysis of bands I and II revealed none of the Cox subunits. In-gel activity staining showed an additional band (Fig.3c, band VII) in membranes of stationary wild-type cells grown under carbon-starved and highly aerobic conditions. ESI-Q-ToF analysis indicated that these membranes contain the cbb3-type as well as the Cox terminal oxidase (Table 3). In any other condition, the cbb3-type oxidase was the only terminal oxidase identified (Table S1), not even one specific peptide belonging to Cox was found after analysis of dozens of samples. Unlike the SLL01 strain, none of the Cox subunits were detected by mass spectrometry analysis in S. oneidensis MR-1 cells cultivated under carbon depletion and microaerobic conditions (Fig. S2). This makes the expression of Cox at any physiologically meaningful levels in these conditions highly unlikely. As a rule, the same pattern was obtained and the same proteins were identified by mass spectrometry when TMPD was used instead of cytochrome c to reveal cytochrome c oxidase activity (data not shown).

Collectively, these results confirm that, among the tested conditions, the Cox A-type oxidase is only expressed in S. oneidensis under highly aerobic and carbon-depleted conditions during the stationary phase. In contrast, S. oneidensis membranes contain the cbb3-type oxidase whatever the culture conditions. Consequently, the cbb3-type oxidase is the only HCO present in S. oneidensis membranes in rich, minimal and iron-depleted media under aerobic and highly aerobic conditions.

Binding sites of regulatory factors in the cox promoter

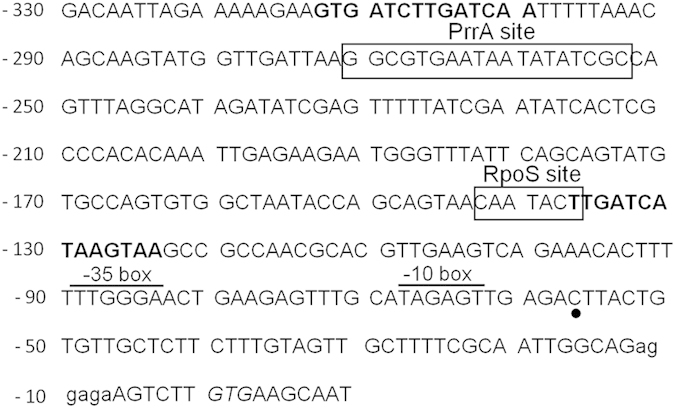

So far, our results clearly indicate that S. oneidensis membranes contain Cox only during the stationary phase under carbon starvation and at high O2 tensions. With respect to the regulatory mechanism that enables this conditional expression, it is interesting that the promoter of the A-type oxidase in P. aeruginosa is induced in the same conditions18. In this bacterium, the cox promoter is activated by the stationary phase sigma factor RpoS and is repressed by the two-component regulatory system RoxSR under low O2 tension. Genes encoding putative RpoS (SO_3432) and PrrBA, a RoxSR analog system (SO_4173 and SO_4172) are found in the genome of S. oneidensis and putative binding sites for the two regulators, RpoS and PrrA, have been identified in the cox promoter inferred from consensus binding sequences21,22,23,24 (Fig. 4). This suggests that the regulatory mechanism involved in the expression of the A-type oxidase in S. oneidensis may be similar to that in P. aeruginosa. Nevertheless, differences between both regulatory mechanisms may exist since Cox was not detected under conditions of iron deficiency in S. oneidensis, while the cox promoter is induced in those same conditions in P. aeruginosa18. Moreover, two predicted Fnr-binding sites are present in the cox promoter of S. oneidensis whereas the cox genes of P. aeruginosa are not regulated by ANR, an analog of Fnr18. In addition to the putative RpoS binding site, putative −10 and −35 boxes for the sigma 70 transcription factor are present in the cox promoter region (Fig. 4), suggesting that both sigma factors are involved in the regulation of expression of the cox operon in S. oneidensis.

Figure 4. Promoter region sequence of the cox operon encoding the A-type cytochrome c oxidase.

The putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence and translation start codon are in lower case and italic, respectively. Predicted Fnr-binding sites are in bold while putative RpoS-and PrrA-binding sites are boxed. Putative transcription start site, −10 and −35 boxes for the sigma 70 transcription factor are indicated by a dot and by horizontal bars respectively. Numbers indicate the position relative to the start codon.

Expression of the bd-type oxidase under nutrient starvation

To investigate the role of the bd-type oxidase in S. oneidensis under nutrient starvation, quinol oxidase activity was polarographically determined in solubilised membranes by measuring O2 reduction in the presence of ubiquinol-1 as the electron donor (Table 4). The presence of the quinol oxidase in the membranes was also analysed by ESI Q-ToF mass spectrometry (Fig. S2 and Table S2) and by light absorption spectroscopy (Fig. S3). When using minimal medium, quinol oxidase activity was significantly lower in highly aerobic conditions than in aerobic conditions. No quinol-dependent O2 uptake was detected in membranes from cultures under iron- and carbon starvation at high O2 tension. However, heme d was spectroscopically detected at 632 nm (Fig. S3) and CydA, one of the two subunits of the bd-quinol oxidase, was identified by mass spectrometry analysis in solubilised membranes of the bacterium in the same conditions (Table S2). This suggests that, for reasons that we cannot currently fathom, the membranes contain the bd-type oxidase but in an inactive form. Furthermore, the same situation is observed in stationary cells grown under microaerobic conditions and carbon starvation, where the bd-quinol oxidase was detected in the membranes but no quinol oxidase activity was measured (Fig. S2). On a more general note, the CydA subunit was identified by mass spectrometry in cytochrome c oxidase activity bands cut out from BN-gels (shown in Fig. 3), run with solubilised membranes of both S. oneidensis MR-1 and the cbb3 deletion mutant grown in all tested conditions (data not shown). This means that the bd-quinol oxidase is present in the membranes of S. oneidensis in virtually all the tested conditions.

Table 4. Quinol oxidase activity in solubilised membranes of S. oneidensis MR-1 under different O2 and nutrient conditions.

| Medium | Growth phasea | Aerobic conditions | Highly aerobic conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| LB | E | 9 +/− 1 | 77 +/− 7 |

| S | 20 +/− 1 | 79 +/− 5 | |

| MM3 | E | 396 +/− 35 | 201 +/− 10 |

| S | 319 +/− 9 | 240 +/− 10 | |

| MM3I− | E | 235 +/− 23 | 0 |

| S | 137 +/− 8 | 0 | |

| MM3C− | E | 521 +/− 13 | 0 |

| S | 0 | 0 |

aExponential (E) or stationary (S) phase of growth.

Activities are expressed in nmol O2.min−1.mg protein−1.

Listed values are averages of at least three separate experiments (mean +/− standard deviation).

As compared to any condition involving rich medium, quinol oxidase activity levels were much higher in aerobic cells exponentially growing in minimal medium, either iron-deplete or low carbon (Table 4). These high activities are comparable to those measured under microaerobic conditions in rich medium14, which leads us to believe that the bd-type oxidase may have an important role under aerobic nutrient starvation conditions. Nevertheless, the expression of the bd-type oxidase must be regulated by other factors than is the case for Cox, since quinol oxidase activity was higher under high O2 tensions in rich medium, and no activity was detected in cells harvested at the stationary phase under carbon starvation in aerobic conditions. It is noteworthy that the bd quinol oxidase activity is not at all detected under the culture conditions where Cox is expressed in S. oneidensis membranes.

Discussion

In this work, we investigated the effect of nutrient starvation on the expression of the terminal oxidases in S. oneidensis MR-1 under different O2 tensions. Our results reveal that their expression is indeed not only affected by the O2 concentration and the growth phase but also by nutrient starvation, depending on the type of nutrient involved. The bd quinol oxidase was significantly induced in aerobic conditions under nutrient depletion, whereas it was only weakly expressed in rich medium14,17. This is in accordance with the fact that the enzyme is required for growth under various unfavourable conditions such as low iron availability5,25. However, the bd quinol oxidase was not involved in respiration under nutrient depletion in highly aerobic and microaerobic conditions. Although the cbb3-type oxidase was identified in S. oneidensis membranes in all tested culture conditions, its expression was still modulated by the nutrient composition of the medium, with especially iron starvation resulting in a strong expression in exponentially growing cells.

The most noteworthy outcome of this study is that the A-type cytochrome c oxidase in S. oneidensis is not functionally lost but expressed in very specific conditions, that is to say under carbon-depleted and highly aerobic conditions in stationary-phase cells. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits a HCO expression pattern similar to S. oneidensis, with the promoter of the A-type oxidase being induced under nutrient-starved conditions18,19. The two transcriptional regulators involved in cox gene regulation in P. aeruginosa, RpoS and RoxSR, are also present in the genome of S. oneidensis; putative binding sites for these two regulators have been identified in the cox promoter region, suggesting that the regulatory mechanism involved in the expression of cox may be similar in the two bacteria. In the PrrBA system, a RoxSR analog system operating in Rhodobacter sphaeroides, PrrA serves as a response regulator, and PrrB26 is a membrane sensor which phosphorylates PrrA upon O2 deprivation27. After growth of P. aeruginosa on rich media in highly aerobic conditions, the O2 tension decreases in the stationary phase due to the high cell density, which causes RoxSR to repress the cox promoter. Conversely, under highly aerobic and nutrient-depleted conditions, biomass remains low when the cells enter the stationary phase and the A-type oxidase is expressed since the high O2 concentration prevents the repressor effect of RoxSR18,19. Another transcriptional regulator that activates the cox promoter in P. aeruginosa is the stationary phase sigma factor RpoS. This factor was found to be involved in survival during carbon starvation in several bacterial species28,29,30,31.

In its natural biotope, S. oneidensis likely encounters conditions of carbon starvation and highly O2 tension. Indeed, S. oneidensis was isolated from the sediment of Oneida Lake32, a shallow freshwater lake well-mixed by winds where bottom dissolved O2 levels are often comparable to the highly aerobic condition defined in this study33. In addition, seasonal and spatial variations in nutrient availability can lead to oligotrophic conditions in aquatic systems, especially since Oneida Lake responds quickly to changes in external nutrient influxes due to its short residence time33. In these particular environmental conditions, the question arises what would be the physiological advantage(s) bestowed upon S. oneidensis by the expression of Cox. Firstly, Cox is likely more energy-efficient than the cbb3-type oxidase in carbon-starved environments due to a higher proton-pumping stoichiometry, which requires a relative high substrate (O2) concentration for optimal operation. Secondly, Cox may play an important role in multicellular structures such as cell aggregates, which resemble biofilms morphologically and physiologically. It was previously reported that S. oneidensis cells experiencing highly aerobic carbon starved conditions form aggregates upon addition of calcium chloride at a concentration similar to that found in natural habitats34. In S. oneidensis, O2-dependent autoaggregation was proposed to be a general protective response aimed to reduce the oxidative stress associated with ROS production during aerobic respiration. When cells experience highly aerobic conditions, aggregation may facilitate both the establishment of anaerobic conditions within the structure and the migration into anaerobic zones by gravitation34. This would be a relevant strategy to thrive in redox-stratified environments that are liable to promote cellular ROS formation, since S. oneidensis is hypersensitive to oxidative stress relative to E. coli35. We have also observed this multicellular phenotype upon addition of calcium chloride, which occurred only with stationary-phase cells grown under highly aerobic conditions and carbon starvation (data not shown), shown here to specifically induce Cox. We thus hypothesize that cox expression may be a component of the defense mechanism against oxidative stress under highly aerobic conditions and carbon starvation in cell aggregates. By consuming O2 in the outer part of the aggregate, Cox could contribute to maintaining lower O2 levels inside the structure and thus prevent excessive ROS production. Furthermore, Cox could also supply a part of the energy required to maintain the aggregated structure, allowing S. oneidensis to better adapt to high O2 tensions when carbon sources become scarce, reminding that Cox can extract more energy per unit of carbon by virtue of its high H+/e− ratio. Intriguingly, a previously reported global transcriptome analysis comparing aggregated to unaggregated cells revealed a five to eightfold upregulation of the cox gene cluster, but this result was not further discussed34. Another interesting result revealed by this study34 is that the rpoS gene is upregulated by a factor of four in these conditions. This strengthens our hypothesis on the putative role of this sigma factor in the regulation of the A-type cytochrome c oxidase expression. Unfortunately, no data is available concerning the two-regulatory component PrrBA.

The expression profile of cytochrome c oxidases in S. oneidensis challenges the generally accepted pattern that in a microorganism that grows aerobically and carries both the A-type and the the C-type oxidase, the former is the main terminal oxidase whereas the latter is only expressed under low O2 tensions. It is of note that in the purple photosynthetic bacterium Rubrivivax gelatinosus, whereas the cbb3 oxidase and the bd-type quinol oxidase are required for aerobic respiration and for initiation of photosynthesis, the caa3 oxidase is not induced36. As we already noticed, a similar pattern to S. oneidensis was reported in P. aeruginosa, where the A-type oxidase was not only induced under carbon depletion but also under iron- and nitrogen starvation18. In S. oneidensis we did not observe aggregates in iron-depleted conditions but only under carbon limitation (data not shown). This supports the hypothesis that the specific expression of Cox in carbon starved cells serves to limit oxidative stress in multicellular structures. Furthermore, carbon starvation appears to be crucial for the expression of genes involved in forming the matrix of S. oneidensis biofilms (which is a form of aggregation), and no induction of these genes was observed under nitrogen starvation, in rich or in minimal medium37. It should be noted that although the formation of aggregates necessitated the addition of calcium chloride to the medium, since this was at concentrations encountered in the native environments of S. oneidensis, this can be considered a limitation of the medium rather than an artificially imposed condition.

Taken together our results indicate that S. oneidensis possesses elaborate regulatory mechanisms to fine tune the expression of the different terminal oxidases, enabling it to thrive in stratified environments where O2 tension and nutrient concentration often fluctuate. This is further illustrated by the fact that the induction of the cox genes is compensated towards lower O2 tensions when the cbb3-type oxidase is lacking, since Cox is detected in all aerobic conditions in the cbb3-deletion mutant SLL01 under carbon starvation. Further study of these regulatory mechanisms will help to identify and understand the different factors that influence the expression of the terminal oxidases in S. oneidensis.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Mutant strain SLL01 was constructed via in-frame deletion of the gene encoding the catalytic subunit of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase (ccoN, SO_2364) in S. oneidensis MR-1, as previously reported14. The strains were maintained on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates and were grown in LB medium or in MM3 minimal medium (pH 6.5) containing 30 mM HEPES buffer, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.5 mM K2HPO4, 85.5 mM NaCl, 18.7 mM NH4Cl, 0.225 mM CaCl2, 0.65 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, 0.5 g.L−1 casamino acids, 0.1 g.L−1 yeast extract, 20 mM sodium DL-lactate and 1 mL.L−1 of trace element solution38. The nutrient starvation experiments were carried out in MM3C− (carbon starvation) or in MM3I− (iron starvation), which correspond to MM3 medium without sodium DL-lactate or without FeCl2 in the trace element solution, respectively. Cultures were performed at 30 °C in a 30-L BIOSTAT® Cplus-C30-3 fermentor (Sartorius BBI Systems, Germany) as reported previously14. The O2 partial pressure sensor (InPro® 6820, Mettler-Toledo) was calibrated at 100% in air-saturated medium at 30 °C, which corresponded to an estimated O2 concentration of 240 μM. The pO2 was regulated at a minimum of 70% (~165 μM O2), at 40% (~95 μM O2) or at a maximum of 6.5% (~15 μM O2) for highly aerobic, aerobic and microaerobic conditions, respectively. During growth, samples were taken from the cultures at the exponential and stationary phases, cells were harvested 10 min at 11400 g and pellets were frozen at −80 °C. For growth parameter measurements, strains were inoculated at an OD600 of ~0.1 in 500 mL-flask with baffled base containing 100 mL of medium, and were aerobically grown at 30 °C in an orbital shaker at 200 rpm.

Preparation and solubilisation of membranes

Membranes were prepared from cell pellets and solubilised with 1% n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM) (w/v) as described before14. Protein concentration was determined with the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich).

Spectral analysis on solubilised membranes

Reduced minus oxidized difference absorbance spectra of DDM-solubilised membranes, pre-incubated with 50 μM potassium cyanide for 10 min, were recorded on a Lambda 25 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer) at room temperature. Potassium ferricyanide at 1 mM was used as the oxidizing agent and membranes were successively reduced by addition of a few grains of sodium ascorbate and sodium dithionite.

Heme extraction and HPLC analysis

Non-covalently bound hemes were extracted from non-solubilised membranes as previously described39. After evaporating solvent using a vacuum concentrator, the dry materials were stored at −80 °C. Residues were dissolved in 100 μL of acetonitrile +0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and passed through a 0.45 μm filter before HPLC analysis. Hemes were separated by reversed-phase HPLC using a Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (5 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm, Agilent Technologies) and detected at 405 nm using a photodiode array detector (Agilent Technologies). The chromatographic separations were performed with a nonlinear gradient of acetonitrile and water with 0.05% TFA at a flow rate of 1 mL.min−1. An initial linear gradient of acetonitrile from 45–72.5% over 11 min was followed by a slow increase to 100% acetonitrile (by t = 30 min) and a rapid drop to 45% acetonitrile (by t = 40 min). Hemes were identified by comparison with the retention times of chloroprotoporphyrin IX iron (III) (hemin, which corresponds to heme b) and heme a extracted from the cytochrome c oxidase from bovine heart (both from Sigma-Aldrich).

Cytochrome c oxidase activity and O2 uptake measurements

Reduction of horse heart cytochrome c with sodium ascorbate and cytochrome c oxidase activity measurements were performed as previously described14. Oxygen reductase activity in solubilised membranes was polarographically measured with a Clark-type O2 electrode (Oxygraph, Hansatech Instruments) in a stirred volume of 1 mL of 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, using either ubiquinol-1 or TMPD as electron donor. Ubiquinol-1 was prepared from ubiquinone-1 (Sigma-Aldrich) by resuspension in absolute ethanol and reduction with zinc powder in 5 M hydrochloric acid solution, and stored protected from light at −20 °C. Quinol oxidase activity was determined with 375 μM ubiquinol-1 and 10 mM dithiothreitol. TMPD oxidase activity assays were carried out with 100 μM TMPD and 10 mM sodium ascorbate. Reactions were initiated by the addition of DDM-solubilised membranes and the consumption of O2 was recorded at 30 °C. Data were analyzed using the O2View software (version 1.02; Hansatech Instruments).

Separation by Blue-native (BN) gel electrophoresis and in-gel enzymatic activities

BN-gels were performed according to the method of Schägger40 as described by Le Laz et al. (2014)14. Cytochrome c oxidase and TMPD oxidase activities were revealed on BN-gels as reported previously41,14. Protein bands were cut out from the gel and stored at −20 °C before mass spectrometry analysis.

Protein identification by in-gel digestion and mass spectrometry

Tryptic digestion experiments, electrospray quadrupole time of flight (ESI-Q-ToF) analyses, processing of the spectra and protein search were performed as previously described14.

Cox promoter sequence analysis

BDGP Neural Network Promoter Predictor program was used to predict the putative transcription start site (http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html) of the cox operon. Virtual Footprint software (version 3.0) was used to identify a −10 box for a sigma 70 factor42.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Le Laz, S. et al. Expression of terminal oxidases under nutrient-starved conditions in Shewanella oneidensis: detection of the A-type cytochrome c oxidase. Sci. Rep. 6, 19726; doi: 10.1038/srep19726 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cécile JOURLIN-CASTELLI and Vincent MEJEAN (CNRS, BIP, Marseilles, France) for kindly providing the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 strain and Ariane ATTEIA (CNRS, BIP) for assistance with HPLC experiments. We acknowledge Robert VAN LIS (Biospector), Marianne GUIRAL and Régine LEBRUN (CNRS) for critical reading of the manuscript. The Proteomic platform is a member of Marseille Protéomique (http://map.univmed.fr/index.html) labeled IBiSA. This work was supported by a research grant from the French Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (Algo-H2 project, ANR-10-BIOE-0004).

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.L.L., M.R. and M.Br. conceived and designed the experiments. S.L.L., M.Br., A.K., M.Ba. and S.L. performed the experiments. S.L.L., A.K., S.L. and M.Br. analyzed the data. S.L.L. and M.Br. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Hau H. H. & Gralnick J. A. Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 237–258 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson J. K. et al. Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat Rev. Microbiol. 6, 592–603 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealson K. H. & Scott J. In The Prokaryotes (ed. Dworkin M.) 1133–1151 (Springer-Verlag, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Baraquet C., Theraulaz L., Iobbi-Nivol C., Mejean V. & Jourlin-Castelli C. Unexpected chemoreceptors mediate energy taxis towards electron acceptors in Shewanella oneidensis. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 278–290 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisov V. B., Gennis R. B., Hemp J. & Verkhovsky M. I. The cytochrome bd respiratory oxygen reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 1398–1413 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffre A., Borisov V. B., Mastronicola D., Sarti P. & Forte E. Cytochrome bd oxidase and nitric oxide: from reaction mechanisms to bacterial physiology. FEBS Lett. 586, 622–629 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Horsman J. A., Barquera B., Rumbley J., Ma J. & Gennis R. B. The superfamily of heme-copper respiratory oxidases. J. Bacteriol. 176, 5587–5600 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M. M., Santana M. & Teixeira M. A novel scenario for the evolution of haem-copper oxygen reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1505, 185–208 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. K. & Cook G. M. Redundancy of aerobic respiratory chains in bacteria ? Routes, reasons and regulation. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 43, 165–224 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. et al. Adaptation of aerobic respiration to low O2 environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14109–14114 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. L. & Schmidt T. M. Shallow breathing: bacterial life at low O2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 205–212 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. C. et al. Molecular genetics of the genus Paracoccus: metabolically versatile bacteria with bioenergetic flexibility. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1046–1078 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberg J. F. et al. Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 1118–1123 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Laz S. et al. A biochemical approach to study the role of the terminal oxidases in aerobic respiration in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. PLoS One 9, e86343 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marritt S. J. et al. The roles of CymA in support of the respiratory flexibility of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 1217–1221 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H. et al. Crp-dependent cytochrome bd oxidase confers nitrite resistance to Shewanella oneidensis. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 2198–2212 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G. et al. Combined effect of loss of the caa3 oxidase and Crp regulation drives Shewanella to thrive in redox-stratified environments. Isme J. 7, 1752–1763 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami T., Kuroki M., Ishii M., Igarashi Y. & Arai H. Differential expression of multiple terminal oxidases for aerobic respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1399–1412 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H. Regulation and function of versatile aerobic and anaerobic respiratory Metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2, 103 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hederstedt L. Heme A biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 920–927 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laguri C., Phillips-Jones M. K. & Williamson M. P. Solution structure and DNA binding of the effector domain from the global regulator PrrA (RegA) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides: insights into DNA binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 6778–6797 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M., Hawkins A. C., Harwood C. S. & Greenberg E. P. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa RpoS regulon and its relationship to quorum sensing. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 973–985 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L. et al. Combining microarray and genomic data to predict DNA binding motifs. Microbiology 151, 3197–3213 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Pinar R., Ramos J. L., Rodriguez-Herva J. J. & Espinosa-Urgel M. A two-component regulatory system integrates redox state and population density sensing in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7666–7674 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook G. M. et al. A factor produced by Escherichia coli K-12 inhibits the growth of E. coli mutants defective in the cytochrome bd quinol oxidase complex: enterochelin rediscovered. Microbiology 144, 3297–3308 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. K. & Kaplan S. Cis-acting regulatory elements involved in oxygen and light control of puc operon transcription in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 174, 1158–1171 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraso J. M. & Kaplan S. prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 176, 32–43 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen F. et al. RpoS-dependent stress tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 145, 835–844 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann M. P., Kidwell J. P. & Matin A. The putative sigma factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173, 4188–4194 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh S. J. et al. Effect of rpoS mutation on the stress response and expression of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181, 3890–3897 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz F. H. & Schoolnik G. K. Role of rpoS in stress survival and virulence of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 180, 773–784 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. R. & Nealson K. H. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science 240, 1319–1321 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington S. et al. Oneida Lake state of the lake and watershed report. New york (2003). [Google Scholar]

- McLean J. S. et al. Oxygen-dependent autoaggregation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1861–1876 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. et al. Protection from oxidative stress relies mainly on derepression of OxyR-dependent KatB and Dps in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 196, 445–458 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassani B. K. et al. Adaptation to oxygen. Role of terminal oxidases in photosynthesis initiation in the purple photosynthetic bacterium, Rubrivivax gelatinosus. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19891–19899 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J., Shukla S., Jost K. A. & Spormann A. M. The mxd operon in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is induced in response to starvation and regulated by ArcS/ArcA and BarA/UvrY. BMC Microbiol. 13, 119 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset M. et al. New shuttle vectors for the introduction of cloned DNA in Desulfovibrio. Plasmid 39, 114–122 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubben M. & Morand K. Novel prenylated hemes as cofactors of cytochrome oxidases. Archaea have modified hemes A and O. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21473–21479 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H., Cramer W. A. & von Jagow G. Analysis of molecular masses and oligomeric states of protein complexes by blue native electrophoresis and isolation of membrane protein complexes by two-dimensional native electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 217, 220–230 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiral M. et al. New insights into the respiratory chains of the chemolithoautotrophic and hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. J. Proteome Res. 8, 1717–1730 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch R. et al. Virtual Footprint and PRODORIC: an integrative framework for regulon prediction in prokaryotes. Bioinformatics 21, 4187–4189 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.