Abstract

Fillers belong to the most frequently used beautifying products. They are generally well tolerated, but any one of them may occasionally produce adverse side effects. Adverse effects usually last as long as the filler is in the skin, which means that short-lived fillers have short-term side effects and permanent fillers may induce life-long adverse effects. The main goal is to prevent them, however, this is not always possible. Utmost care has to be given to the prevention of infections and the injection technique has to be perfect. Treatment of adverse effects is often with hyaluronidase or steroid injections and in some cases together with 5-fluorouracil plus allopurinol orally. Histological examination of biopsy specimens often helps to identify the responsible filler allowing a specific treatment to be adapted.

KEYWORDS: Complications, fillers, hyaluronic acid, blindness

INTRODUCTION

Volumetric rejuvenation of the face with fillers has gained popularity as the least invasive intervention. However complications can occur. Some adverse effects are transient such as erythema and edema, whereas some may persist such as granulomas. The management of complications depends on several factors.

Severity of the adverse effect: Most of the immediate side effects are minor and disappear on their own. Moderate side effects require treatment that is usually conservative. Severe adverse effects may necessitate an immediate intervention.

Duration of the adverse effect: Generally, adverse effects last as long as the desired filler effects. This is true for most of the fillers. However, with collagen they may persist. A middle-aged woman was seen developing stone-hard swellings at each point where she was injected with bovine collagen, even at the test site, and despite all treatments these granulomas did not regress. Collagen injections have a risk of approximately 6% to produce granulomatous reactions and usually respond to corticosteroid injections within a few weeks. Adverse side effects to hyaluronic acid fillers were frequently seen at the beginning of their use, probably due to the protein moiety that is part of the biosynthetic production procedure. These swellings commonly remained at the site of injection and disappeared with adequate treatment; however they are now infrequent. Clumping of a filler causes lumps and bumps that usually have to be surgically removed. Permanent fillers cause permanent side effects.

Time course of adverse filler effects: The time course is divided into reversible or temporary (caused by collagen and hyaluronic acid); late and long-term (caused by poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA), calcium hydroxylapatite, alginate, and dextranomer beads in hyaluronic acid); and delayed and permanent (caused by vaseline, paraffin, silicone oil, hydroxyethyl methacrylate fragments, polymethylmethacrylate beads, polyacrylamide, and polyalkylimide gels).

There is a general misconception that temporary fillers rarely provoke side effects; the frequency is comparable to that induced by long-term and permanent fillers but their duration is shorter and hence, they are less serious.

COMPLICATIONS

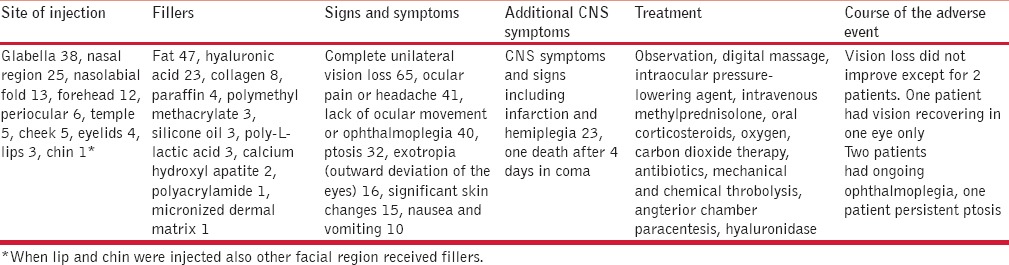

Early side effects include erythema, edema, and bruising; they are in fact a normal physiological reaction to the injection of a foreign substance and can often be mitigated by cooling the injected area. Pain is reduced by slow injection and administration of local anesthetics in small volumes. Bruises are said to be reduced by using arnica, aloe vera, or vitamin K creams. Allergies may occur within hours in cases where the patient has been sensitized before. Lumps and bumps occur when an unsuitable filler is injected superficially or in the wrong location. These may occur immediately or develop from clumping of the substance due to muscle activity. Vascular compromise becomes evident within a day in case of arterial occlusion due to inadvertent intravascular injection or compression by the filler volume. Using a blunt cannula instead of a sharp injection needle prevents inadvertent intravascular injection.[1] This is particularly dangerous for the glabella, inner corner of the eye, and ala nasi, and is reported to cause skin necrosis and even blindness.[2,3] A review of the world literature on eye complications from filler injections identified 98 cases in English-language journals [Table 1]. Most cases were due to autologous fat (n=47), hyaluronic acid (n=23) and collagen (n=8), whereas all other substances used as fillers were below 5%. Fifty-nine cases were reported from South Korea where the data were collected from the major retinal centres.[4] Whenever blanching is seen during the injection, it must be stopped immediately.[5] Hyaluronidase is injected around the vessel in order to prevent the side effects caused by hyaluronic acid filler. Aggressive massage, warm compresses, and topical nitroglycerin are further supportive measures.[6,7,8]

Table 1.

Eye complications from fillers (adapted from Beleznay et al.[3])

Late complications are defined as those appearing after about 2-6 weeks. They comprise late allergic reactions, chronic inflammation and infection, granulomas, filler migration, loss of function, telangiectasia, and hypertrophic scars. A detailed history may disclose a potential allergy. To avoid infection, the injection site has to be thoroughly disinfected and defatted and the injection must not be done through makeup.[9] Infection should be immediately treated with antibiotics and usually responds quickly. Granuloma formation is unpredictable but depends on the material used. Particulate material is prone to induce a macrophagic reaction, particularly the permanent fillers, but also poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) the particles of which have a crystalloid structure. The probability of granulomas increases with the surface-to-volume relation of the filler particles and their shape with sharp edges. Homogenous fillers rarely induce granulomas. Good quality hyaluronic acid fillers are virtually devoid of this effect. Silicone oil provokes a slightly different reaction called siliconoma with lymphocytic infiltrates. Permanent fillers on the basis of acrylate gels appear homogenous but are, in fact, particulate.

Delayed reactions are those that occur 6 weeks after the filler injection. They are caused mainly due to bacterial biofilms,[10] although this view has been vehemently disputed. They may induce granulomas as well as the so-called cold abscesses. As biofilms are mostly bacterial in nature, they should not be treated with steroid injections.[11]

Delayed side effects may develop months or years after the placement of the filler, and the patient often does not remember which filler he/she had got and whether other fillers had also been used. Nonphysician injectors are often ignorant of the side effects of the fillers they use, and they also neglect good clinical practices such as disinfection and wearing of gloves.

ADVERSE EFFECTS ACCORDING TO TYPE OF FILLERS

Most adverse effects are not specific to a particular filler. They may be the result of volume augmentation or due to technical faults such as wrong indication, placement site, wrong injection needle,[12] and infection caused by contaminated ice or water.[13] Infections are differentiated from other nodules and granulomas by radiolabeled leukocyte scintigraphy.[14] Inflammatory and immune-mediated adverse effects often occur late. Persistent edema, granulomas,[15] sarcoid-like reactions, and panniculitis are the most common side effects. Systemic granulomatous, autoimmune diseases and acute hypersensitivity reactions are very rare.[16] Manipulation close to an injection site may lead to infection even years after the placement of the filler.[17]

Autologous fat

Adherence to key principles, such as sterile technique and low-volume injection throughout layers of tissue, is necessary for obtaining excellent results. Adverse outcomes are rare. However, early adoption of surgical procedures by those without a sound understanding of the underlying principles and techniques can have disastrous consequences. Furthermore, physicians operating on any patient must understand the potential for complications and be able to manage these appropriately when they occur.[18] Fat longevity is dependent upon methods of handling and preparation of the fat. Poor fat viability produces an inadequate result. This has thus to be considered as a complication.[19]

On the other hand, poor aesthetic results due to significant weight gain as a result of corticosteroids, oral contraception, and a change of lifestyle were seen in a patient with Romberg's syndrome.[20] Lipomodelling of the breast was performed in 880 cases, approximately 140 mL of filler was injected for a desired volume of 100 mL, which remained stable for 3-4 months. No radiological problems at mammography occurred after the procedure. Fat necrosis was observed in only 3% of the cases. Serious complications included one case of infection at the harvest site, six cases of infection at the injection site, and one case of intraoperative pneumothorax.[21] Abscess formation, life-threatening sepsis, and residual deformity have also been reported.[18]

A recent review of the English-language literature revealed 98 cases of vision change due to filler injections, of which 47 were due to autologous fat injection; one patient experienced necrosis of her left eye after 2 days and died after 4 days.[4] Neurological complications after fat injection comprised 2 patients with unilateral loss of vision after fat injection in glabella,[22] 2 patients with sudden loss of vision, aphasia and hemiparesis[23] and 1 patient with sensorimotor hemiparesis after infarction of the middle cerebral artery.[24] Three preconditions that predispose to intravascular fat embolism include well-vascularized tissue, a sudden local increase in pressure in the injected tissue and fragmentation of parenchyma.[25] It is assumed that fragments of fatty tissue reach ocular and cerebral arteries by reversed flow through branches of the carotid arteries from the facial vessels. Complication of fat embolism can appear either immediately after the fat injection or after a latency period. It may remain subclinical and may not be recognized, or the clinical features may be misinterpreted.[25] To minimize the risk of such a major complication, it is essential that fat injections should be performed slowly, with the least possible force. Routine funduscopic examination after fat injections into the face may be useful.[25]

Human collagen

Autologous human collagen is well-tolerated, both when derived from cultured fibroblasts and autologous injectable dermis.[26] Human allogeneic collagen was found to elicit acute-to-subacute inflammatory reactions,[27] but no serious long-term side effects were reported. The cosmetic effect lasts 4-7 months.

Nonhuman collagens

Nonhuman collagens are foreign proteins that exhibit a risk of allergies and granulomas, particularly bovine collagen, although porcine collagen is better tolerated. The side effects are mostly temporary until all collagen has been degraded but one case was observed with stone-hard granulomas not disappearing with any treatment over more than a decade.[28] Most granulomas are palisaded around amorphous eosinophilic material representing bovine collagen. This is characterized by structureless deposits, lack of birefringence, and pale gray-violet staining with Masson's trichrome stain.[29] Whether the injection of collagenase[30] would be successful has not been examined. About 4-6% of the patients developed temporary granulomas at the injection site. Testing and double testing before treatment were recommended, and in both cases granulomas were found to occur.

Presently, collagen fillers are used less frequently, and as a result adverse effects are expected to be rare.

Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is universally present in all animal species. It is not species-specific; however, hyaluronans are linked to proteins that are species-specific. Good preparations are (almost) free from foreign proteins. They have a low propensity to induce granulomas, but show a variety of transitory side effects such as rare granulomas and infection.[31,32] Presently, approximately 200 HA preparations are on the market. To prevent untoward adverse effects, high-quality brands with a low rate of problems are preferred as their complication rate is much lower.

Untested cheap products should not be used at all.

HA is currently the most widely used filler. It has a longevity of approximately 6 months, but this depends on the molecular size, method of cross-linking, and the region of injection. There are differences among HA fillers concerning the size of the molecule, the protein content, the chemical bonding, the fluidity, whether they are monophasic or biphasic, injection pain, and longevity.[33] A good preparation does not clump as this may give rise to granulomas. They were not rare in the beginning of the nonanimal-derived synthetic HAs (NASHAs) but are now very rare, except for new, cheap, untested products, particularly bought online through the internet.

In the early period of HA filler use, reactions were assumed to be caused due to hypersensitivity.[34,35] Erythematous multiform rashes and systemic anaphylactoid reactions are very rare side effects[36,37] that occur after intra-articular injection of HA,[29] with native HA having a lower sensitizing potential.[31]

Side effects due to the substance are usually short-lived and can instantaneously be treated by injecting hyaluronidase. The dose depends on the specific drug and also varies according to the HA used and its degree of cross-linking. Hyaluronidase cleaves both natural and cross-linked HA. Bovine, ovine, and recombinant hyaluronidase are available. As they are foreign proteins, they have the potential of causing an anaphylactic shock in sensitized individuals. It is, therefore, necessary to question the patient about possible allergies. Hyaluronidase can also be used to treat HA granulomas.[38]

Technique-related side effects occur as with other fillers as well. HA injected too superficially may shine through with a bluish-grayish color, due to the Tyndall effect [Figure 1]. It has to be used with care in the eyelids as it may cause swelling due to its ability to attract water. Accidental intracapillary injection may cause livedo reticularis.[39]

Figure 1.

Over correction Tyndall effect hyaluronic acid (Courtesy Dr. M Cantisano-Zilkha)

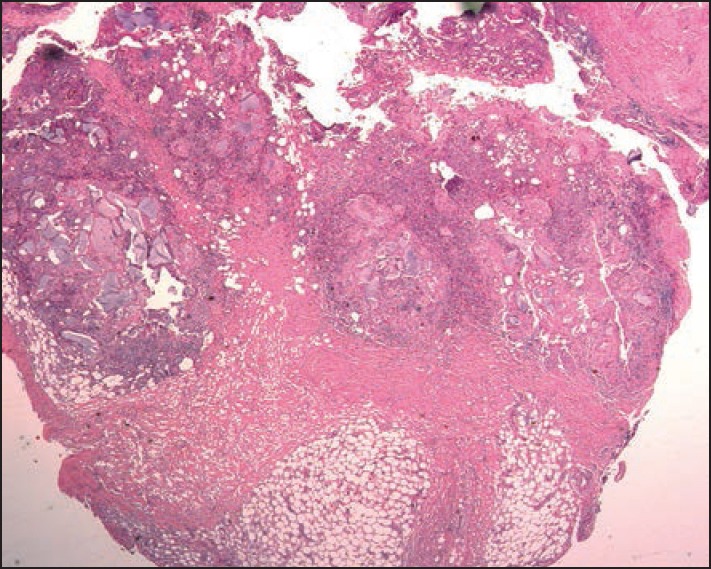

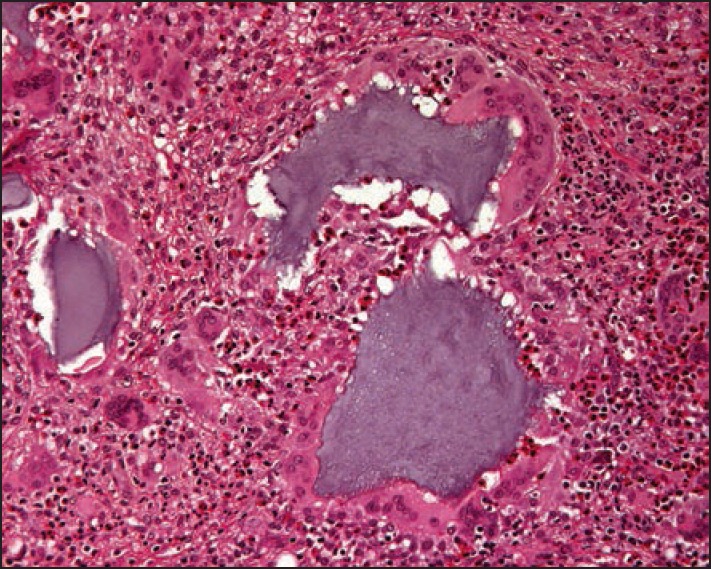

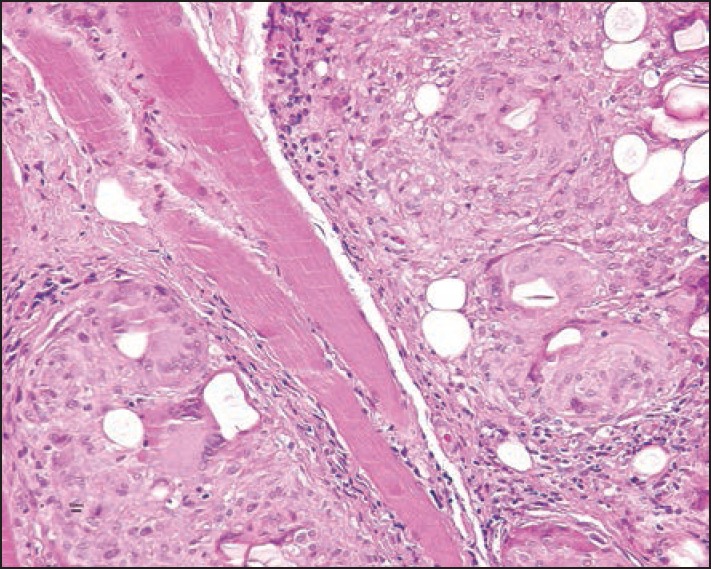

The histopathology of grayish-glassy nodules after superficial injection shows HA deposits without any inflammatory changes. Granulomas exhibit a very dense lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant eosinophils and many foreign body giant cells containing basophilic amorphous material that corresponds to HA [Figures 2–5]. Autoinjected diluted HA cream resulted in a dense inflammatory and granulomatous infiltrate to the abused cream vehicle.[40] It was successfully treated with systemic antibiotics and intralesional steroid injections.

Figure 2.

Reaction after injection of a new hyaluronic acid filler (Hylacorp®)

Figure 5.

Close-up photograph of the hyaluronan granuloma with multinucleated giant cells engulfing the material as well as many eosinophils.

Figure 3.

Scanning microscopy of the excision specimen of the patient shown in Figure 2

Figure 4.

Medium paower histopathology photograph of the hyaluronic acid injection specimen showing clumps of basophilic hyaluronan, giant cells and huge masses of eosinophils

Alginate

In an attempt to develop a new biological filler with a longer duration, an alginate derived filler (Novabel®) was marketed. Very shortly after its launch, the side effects of granulomas were observed;[41] hence, it had to be withdrawn from the market. The granulomas started with erythema and swelling until hard nodules formed 2-5 months after the injection. Ultrasound showed hypoechoic structures with a hyperechoic rim. Histopathology revealed spherical basophil structures of 100-120 μm diameter surrounded by a rim of giant cells. Around the granulomas, a distinct hyaline collagen capsule was seen.

Hyaluronic acid plus dextranomer microspheres

Dextranomer beads were incorporated in HA to improve the longevity of the filler. They consist of cross-linked dextran molecules with a positive surface charge and a diameter of 80–120 μm. The beads attract macrophages that release tumor growth factor-β and interleukins stimulating collagen deposition around the detranomer beads, maintaining the volume correction effect after the resorption of HA.[42] The material is well tolerated with only three reports of a granulomas, one of which was suppurative[35] and the other ones were rich in foreign body giant cells.[43,44] The histopathology shows dark bluish or purplish dextranomer beads, or may exhibit empty spaces giving a “Swiss-cheese” aspect. Incision of the nodules and treatment with cephalexin and methylprednisolone aceponate led to complete resolution in one case.[45]

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA)

This substance has been used for decades in medicine and surgery and is well-tolerated. In contrast, PLLA as a filler comes as a powder of crystalloid particles that has to be reconstituted before injection. Subcutaneous nodules are either fibrotic or granulomas. They can form because of insufficient time during reconstitution of the material, inadequate dilution, overcorrection, superficial injection techniques, or inappropriate concentration of PLLA molecules secondary to muscle movement. Granulomas are thought to be due to allergic or inflammatory host responses.[1] In the early years, a volume of 3 mL of filler was recommended: This was found to cause granulomas and it also clogged the injection needle. Now, most physicians use 10 mL or more of physiologic saline, often with some lidocaine. After injection, the water is resorbed and the PLLA particles induce a fibroblastic reaction lasting for 24 months or longer. This may cause fibrotic nodules around the eyes and in the hands,[46] and the substance may clump in the lips; these are adverse effects of a faulty technique. PLL granulomas are classical giant cell granulomas with many epithelioid cells and relatively few lymphocytes. The PLL particles are oval, fusiform, or spiky, and seen in epithelioid and giant cells as well as in between. They show birefringence in polarized light.[47] The granulomas last for at least 18 months, which approximately represents the time needed to hydrolyze the crystalloid particles.[48]

Calcium hydroxyl apatite

Calcium hydroxyl apatite (CAH) is an inorganic material that has been used successfully as bone cement for decades. The material currently used as a cosmetic filler is Radiesse® (Merz Pharmaceuticals, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). It consists of microspheres (30%) of 25-45 mm diameter suspended in carboxymethyl cellulose (70%) gel. It is biochemically inert and nonantigenic but stimulates collagen production. When injected as a suspension for soft tissue augmentation, it is very well-tolerated. Its filling effect lasts 9-12 months[49] and sometimes longer. Adverse effects are rare and caused mostly due to technical faults. Postinjection cellulitis was reported at a frequency of 1.7% in one study.[50] It must not be injected into the lips as it tends to clump and produce palpable nodules.[51] In elderly women, granulomas were observed that consist of tightly packed dark bluish microspheres of 25-40 μm diameter and giant cells.[52] The nodules were effectively treated by fractional CO2 laser.[53] A grade 3 systemic reaction developed 30 min after the injection of cyclohexyladenosine (CHA) vocal cord filler prompting the authors to recommend a 30-min postprocedure observation period.[54]

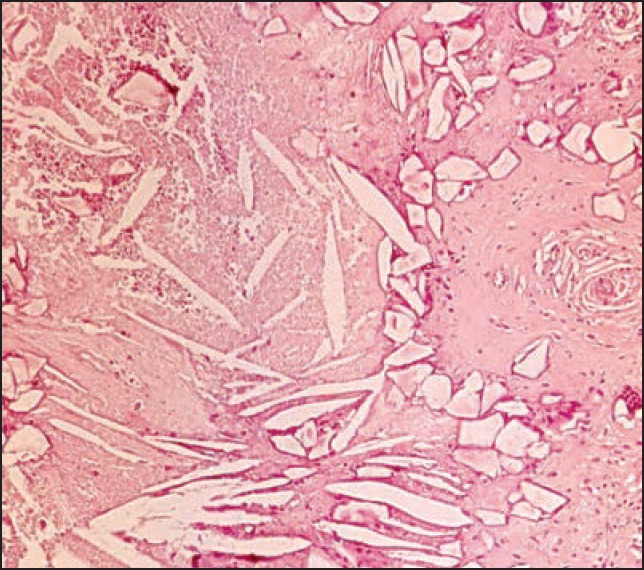

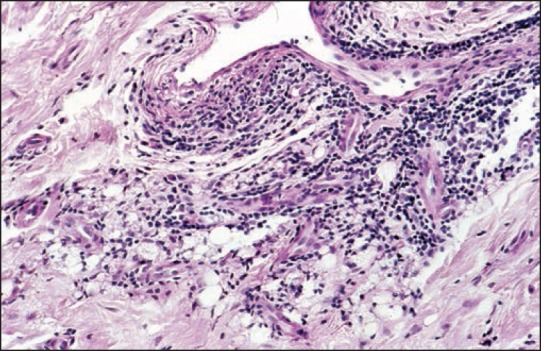

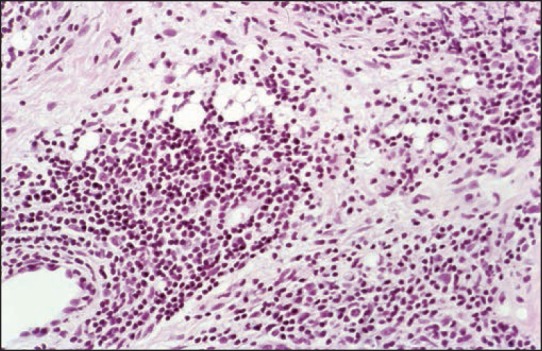

Acrylic hydrogel

Suspension of ethyl methacrylate and hydroxyethylmethacrylate particles in hyaluronic acid was marketed as DermaLive® and DermaDeep®. Initial reports claimed good tolerance level[55] but soon it became evident that this biphasic filler caused late granulomas in a very high percentage of cases[56,57,58] and it had to be withdrawn from the market. However, granulomas still occur.[59] They present as palpable and then often visible nodules [Figures 6 and 7]. Fistulation may develop with time, and occasionally a keratoacanthoma-like appearance is seen.[60] The granulomas are well-delimited and easy to dissect surgically [Figure 8]; however, new granulomas develop until all material has been removed. Other treatment options are intralesional corticosteroids, allopurinol, and 5-fluorouracil. Antibiotics are given immediately if an infection is suspected.[61] The histopathology shows a dense granuloma with a fibrous pseudocapsule containing masses of crystalloid acrylate particles. The granulomas are made up of epithelioid and foreign body giant cells that engulf the particles. Some areas become necrotic and contain cholesterol clefts. Epidermal ridges may grow down and try to surround the foreign material giving rise to fistule formation. Some granulomas may become sclerotic with time [Figures 9–12]. Acrylic hydrogel is probably the product with the highest risk of complications.

Figure 6.

Female patient after injection of acrylic gel (Dermalive)

Figure 7.

Stretching out the skin makes the granulomas more visible.

Figure 8.

Some of the extirpated acrylic gel granulomas

Figure 9.

Scanning microscopy of the acrylic gel granulomas

Figure 12.

Mainly epithelioid cell granuloma with some giant cells and acrylic gel particles

Figure 10.

High magnification of an area in the granuloma showing long slender so-called cholesterol clefts in a necrotic tissue as well as smaller polyedric acrylic particles

Figure 11.

Area of the granuloma with multiple acrylic gel particles

Polyacrylamide gel

Polyacrylamide gel (PAAG) is a suspension of 2.5-5% PAAG in sterile water. It is a large volume filler and can hold 300 to 400 times its weight in water. It is marketed under many different names: PAAG (Sinocos Eastcos, Hong Kong, China); Amazing gel, Aqualift, Aquamid (Contura International, Söborg, Capital Region of Denmark, Denmark); Argiform, Bioformacryl, Formacryl, and Outline, each of which contain slightly different additional components.[1] The material is widely resistant to enzymatic degradation and phagocytosis and hence, it is considered a permanent filler. The particles can harbor bacteria on their surface and give rise to late infections, biofilms, and abscesses.[62] It does not induce allergic reactions. It is mainly used in breast augmentation surgeries, especially in Eastern Europe and Asia. Although the results are immediate, overcorrection is necessary. It remains soft and pliable after injection, which is a major advantage of this filler over other substances.[63] PAAG should not be injected over other products. It is generally well-tolerated; however, severe adverse effects, such as swelling, lumps, abscesses, facial disfigurement, gel dislocation, and respiratory distress, have been known to occur.[64] Other series reported breast deformity, lumpiness, intermittent swelling, pain, and gel extrusion.[64,65,66,67] The gel is exceedingly biocompatible, making it an excellent medium for bacteria.[68] The main risk is infection that often develops after 8-12 months or even later. Cultures frequently remain negative and only PCR can identify bacteria, such as Propionibacterium acnes, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus mirabilis, and Staphylococcus aureus, which are normally not pathogenic and some atypical mycobacteria hinting at the importance of preinjection site disinfection. Histopathology shows neutrophils, karyorrhexis, numerous macrophages, and foreign body giant cells around a gel that appears to be morphologically similar to hyaluronic acid. Giant cells often contain vesicles full of PAAG, and the material frequently shows small blebs in the material are seen both when it is in giant cells as well as in large lakes in the tissue. PAAG is not birefringent but positive with Alcian blue.

Polyalkylimide gel

Polyalkylimide gel 4% in water (Bio-Alcamid, Polymekon, Milan, Lombardy, Italy) is also a large-volume filler. It is injected into the deep dermis or hypodermis. It develops a thin collagen capsule around the site of injection preventing migration and keeping it apart from the surrounding tissue. An advantage is that aspiration or punching a small hole over it permits its removal. Side effects are edema, bruising, nodules, infections, severe inflammatory reactions, unsatisfactory appearance, and late-appearing abscesses. Migration despite the fibrosis around it is a rare event.[69] Histopathology shows basophilic amorphous material surrounded by neutrophils and erythrocytes. Gram stain may reveal bacteria. Infections are very difficult to treat and require long-term high-dose antibiosis, incision, drainage, and irrigation.[70.71]

Polyvinylhydroxide microspheres in polyacrylamide gel

It is a suspension of 6% polyvinyl hydroxide microspheres in 25% PAAG hydrogel (Evolution®, ProCytech SA location details not given). It is reportedly well-tolerated but is not used very often.[53,72]

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) beads suspended in bovine collagen were marketed as Artecoll®, later Artefill® and Artesense®. The products require testing of bovine collagen before use to avoid an immune reaction. Patients with keloids should not be treated with this.[73] Around 3 weeks after injection, collagen is deposited around the microspheres virtually encapsulating them. Overcorrection is not performed. Artefill® polishes microbeads and attracts fewer impurities with less risk of inducing granulomas.[74] Metacrill and Metrex are also PMMA particles but they are not round and polished. Granulomas are a rare side effect with an incidence rate of 0.01%[75,76] but are difficult to treat.[77] Lumps are frequent, particularly in the lips but most are only palpable and not visible. Granulomas develop even several years after the injection[78] and occur after treatment with interferon for hepatitis C[79] or after laser skin resurfacing (D Vochelle, personal communication). Sudden onset of induration, swelling, tenderness, and erythema indicates granuloma. The histopathology reveals a typical granuloma with round empty-appearing clear spaces in a fibrotic tissue. Therapy constitutes intralesional corticosteroids and 5-fluorouracil[80] as well as allopurinol and surgery. Metacrill granulomas are melted with high frequency endocoagulation that leaves a residue of burnt plastic with a characteristic smell.[81] Intralesional laser treatment is another option.

Mineral oils, paraffin, and other lipid derivatives

Vaseline was the first substance to replace a testicle more than 120 years ago. Other crude substances such as paraffin, lanolin, cod liver oil, or beeswax were also used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The initial results were satisfying but the long-term results were appalling with skin hardening, swelling, granuloma formation, ulceration and fistulation, infections, abscesses, and even cancer development.[1]

The side effects of paraffin are irreversible and hence, it is no longer legally used as a filler. Highly inflammatory granulomas after fraudulent use of paraffin or other oils containing vitamin E, sometimes also D and A, are still seen.[82] Injection of paraffin into the penis caused sclerosing lipogranuloma characterized by fibrosis and deformation.[83] Vaseline and other mineral oils cause a very similar reaction.[84,85,86,87]

Histopathologically the deep reticular dermis and subcutaneous fat are involved with a predominantly lobular panniculitis with a Swiss-cheese appearance. The cystic spaces are surrounded by foamy histiocytes and giant cells. The collagen bundles in-between are sclerotic.

Whether ultrasound liquefaction of the fat where the inappropriate substance had been injected, and subsequent extraction by a suction cannula helps to eliminate this material remains to be seen.[88,89]

Silicone

Silicone is a filler with irreversible side effects. It is a highly polymerized hydrophobic oil (Silikon 1000, Adatosil 5000, Biopolimero), gel (MDX 4-4011), or solid rubber consisting of dimethylsiloxane units. It is well-tolerated but the occasional side effects are dramatic and irreversible; therefore, it is banned for cosmetic use in the European Union and the United States. Those who still use silicone off-label claim that pure silicone[90] and proper microdroplet technique prevent adverse effects but this view is disputed. Medical grade silicone oil is pure and sterile. The secret of good results is the injection of truly minute amounts.[91,92,93] A mixture of silicone with hyaluronic acid was recently described as “the optimal filler.”[94]

Side effects are local and systemic. Small nodules are minor complications that occur within a year after injection. They occur due to injection of too much substance. Indurations and erythema with swelling are silicone granulomas that frequently appear 2-12 years after injection. Some authors differentiate between siliconoma, which consists almost exclusively of macrophages containing small droplets of silicone oil and contains virtually no inflammatory cells, and silicone granuloma, with silicone containing macrophages, lymphocytes [Figures 13 and 14], and few giant cells that are somewhat artificial. Both respond to intralesional corticosteroids in most cases. Major complications are systemic with pneumonitis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sudden death after intravascular injection, migration of large volumes of low-viscosity silicone oil, erysipelas-like reactions, blindness, loss of neurologic functions, and death after silicone oil was inadvertently injected into the ophthalmic or meningeal vessels.

Figure 13.

Dense lymphocytic infiltrates around vessels and small silicone droplets (lower margin) reminiscent of small fat cells

Figure 14.

Adverse reaction to silicone displaying small silicone droplets

Silicone elastomer particles

Silicone elastomer particles (SEP) suspended in polyvinylpyrrolidone plasdone hydrogel (Bioplastique®) were used in urology and for vocal cord augmentation. It causes some lumps and granulomas.[95,96]

GENERAL CONSIDERATION ON THE HISTOPATHOLOGY OF ADVERSE FILLER EFFECTS

Many fillers display a specific morphology and/or staining pattern in the skin.[52] This is both true for acute reactions when the filler is still visible as well as for late reactions such as granulomas and infections with abscesses.

Bovine collagen is seen as a dense eosinophilic mass in the skin. It is not birefringent like human collagen fibers. Early “allergic” reactions show a lymphocytic infiltrate that may turn into a granuloma with many epithelioid cells and some intermingled giant cells.

HA is sometimes seen in the skin as a structureless basophilic substance, corresponding to the Tyndall effect when localized very superficially. Granulomas were seen in the early times of manufacturing of streptococcal HA, most probably due to the content of bacterial protein. This is extremely rare with this product. Another brand new filler caused many granulomas and abscesses with a dense lymphocytic infiltrate, many giant cells, often of excessive size, and abundant eosinophils around basophilic HA. In case of abscesses and fistulation, the foci of neutrophils are seen.

Matridex demonstrates both hyaluronic acid as well as dextranomer beads in a cell-rich granuloma. The microspheres are perfectly round and darkly basophilic or purple allowing the product to be identified.

PLLA is seen as crystalloid material in epithelioid cell granulomas with giant cells often surrounded by fibrosis. The material is birefringent permitting its exact identification.

Acrylic hydrogel mainly causes late granulomas and no HA is seen any more. The acrylic particles are polyedric and seen in a dense granuloma with giant cells, many of which try to phagocytose the foreign bodies. Necrotic areas are frequent and contain cholesterol clefts. Clinically visible fistulae correspond to epidermal ingrowths trying to engulf and transepidermally eliminate filler materials.

PMMA (Artecoll, Artefill) is seen as round empty-appearing spaces in a fibrotic tissue. Although appearing to be of relatively uniform size, this depends on the section plane of the beads. Epithelioid and giant cells are seen in granulomas.

PAAG is biologically well-tolerated. The main risk is infection that may cause abscesses and necroses. Granulomas contain epithelioid and giant cells. The material is basophilic and does not exhibit a wavy structure often seen with hyaluronic acid.

Silicone oil causes granulomas with droplets of varying size, some of which are seen in epithelioid cells. Giant cells are rare as there are no particles. Dense lymphocytic infiltrates are mainly seen in perivascular localization.

Sclerosing lipogranuloma is a characteristic feature of paraffin and vaseline injections, mainly in the penis to increase its girth. It is characterized by a Swiss-cheese-like aspect in a fibrotic tissue with lymphocytes, epithelioid, and giant cells. The empty spaces are of variable size.

The injection of vitamin E in different oils gives a similar histopathological picture but as these injections are now mainly used in the face, particularly in the lips, by nonmedical persons the changes are much more acute and the inflammatory component is more obvious in these cases.

IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Imaging techniques were introduced in the diagnosis of filler complications, particularly for suspected abscesses. Other indications are overfilling, migration, foreign-body granulomas, and scarring.[97] High-frequency ultrasound complemented with magnetic resonance imaging and white blood cell scintigraphy permitted the distinction between infections, fibrosis, granulomatous inflammation, and product migration.[98] Calcium hydroxylapatite is radio-opaque, and can be seen in normal radiographs.[99] Its injection may cause local hypermetabolism, and it can be a source of false-positive findings in positron emission tomography (PET) scans.[100,101] Using conventional x-ray films and computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, a distinction of different materials is often possible.[102]

GENERAL TREATMENT REMARKS

Prevention is always better and easier than treatment. After identifying the filler substance and the exact nature of the adverse side effect, the appropriate therapy is chosen. Early side effects such as injection pain, immediate swelling, and edema usually do not require specific treatment. Cooling is sufficient to alleviate the immediate postinjection pain; however, this is rare after the addition of lidocaine as a local anesthetic. Swelling may respond to acetylsalicylic acid or another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Placement of too much material or in the wrong area requires immediate massage or removal, if possible. Lump formation after CAH injection in the lip is a technical fault as well as too superficial an injection. Proper training for injecting this substance is mandatory.

Blanching extending beyond the immediate area of the injection volume may be a sign of vascular occlusion. Nitroglycerin cream and warming may be sufficient in mild cases.[14]

HA can be rapidly dissolved with hyaluronidase. Most of these enzyme preparations are of animal origin and there is the theoretical possibility of a sensitization. It is wise to use one preparation to get experience with it as the dosage may vary among the different drugs. The effect is usually seen within hours, and reinjection is possible after 24 h; so small doses are recommended in the beginning.

The treatment of late and delayed adverse effects is challenging. First, the responsible substance has to be identified. This is often difficult as the patients do not know, or are reluctant to disclose, which filler was injected. Once a granuloma developed, it is to be assumed that more granulomas will continue to develop as long as the foreign material is in the skin. It is not evident whether fillers can be reliably identified on attenuated total reflectance/Fourier transform infrared analysis spectroscopy.[103] Another validated method is the histological examination of sections, which yield quite specific changes with most different fillers.[64,104]

The differentiation of infection from noninfectious granulomas is possible with radioactive labeled leukocytes. In case of infection, antibiotics have to be given for a long period and in doses capable of preventing the infection. Staphylococcus-fast antibiotics, such as cephalosporins, are given intravenously.[105] Vancomycin is used against Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Granulomas often respond to intralesional injection of a mixture of 5-fluorouracil (250 mg/mL), triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/mL) plus mepivacaine (1 mL), which is given first twice a week and then once a week;[106] in addition to allopurinol given in a dose of 300-600 mg/day.[107] TNF-α inhibitors have not yet gained much acceptance in the treatment of granulomas.

CONCLUSION

Fillers are the most frequently used substances in aesthetic medicine. The “consumers” are not sick individuals, but healthy persons expecting to look better after the procedure. Any adverse effect is a catastrophe for them and for the treating physician. The following measures have to be taken to avoid the adverse effects: The physician must be well-trained, the best product must be used, and indications, contraindications, proper aseptic injection techniques, and adequate localization for each specific filler to be injected should be respected. The client has to follow the physician's recommendations after treatment. The best would be to give a “filler pass” to the patient that notes which filler was injected when and where. Despite all precautions, adverse effects may occur. The physician should take these adverse effects very seriously and never dismiss a patient's concerns. The treatment should be instituted as soon as possible.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fulton J, Caperton C, Weinkle S, Dewandre L. Filler injections with the blunt-tip microcannula. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1098–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, Nardi M, Pantaloni M, Lazzeri S. Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:995–1012. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182442363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park SW, Woo SJ, Park KH, Huh JW, Jung C, Kwon OK. Iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:653–62.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beleznay K, Carruthers JDA, Humphrey S, Jones D. Avoiding an treating blindness from fillers: a review oif the world literature. Dermatol surg. 2015;41:1097–117. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glaich AS, Cohen JL, Goldberg LH. Injection necrosis of the glabella: Protocol for prevention and treatment after use of dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:276–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL, Carruthers JD. Successful management of an unusual presentation of impending necrosis following a hyaluronic acid injection embolus and a proposed algorithm for management with hyaluronidase. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:357–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narins RS, Jewell M, Rubin M, Cohen J, Strobos J. Clinical conference: Management of rare events following dermal fillers — focal necrosis and angry red bumps. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:426–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleydman K, Cohen JL, Marmur E. Nitroglycerin: A review of its use in the treatment of vascular occlusion after soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1889–97. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiore R, 2nd, Miller R, Coffman SM. Mycobacterium mucogenicum infection following a cosmetic procedure with poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:353–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen JL. Understanding, avoiding, and managing dermal filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(Suppl 1):S92–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen L, Breiting V, Bjarnsholt T, Eickhardt S, Høgdall E, Janssen M, et al. Bacterial infection as a likely cause of adverse reactions to polyacrylamide hydrogel fillers in cosmetic surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1438–44. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niamtu J., 3rd Filler injection with micro-cannula instead of needles. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2005–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez JM, Xie YL, Winthrop KL, Schafer S, Sehdev P, Solomon J, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae facial infections following injection of dermal filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:265–9. doi: 10.1177/1090820X12471944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grippaudo FR, Pacilio M, Di Girolamo M, Dierckx RA, Signore A. Radiolabelled white blood cell scintigraphy in the work-up of dermal filler complications. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:418–25. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colbert SD, Southorn BJ, Brennan PA, Ilankovan V. Perils of dermal fillers. Br Dent J. 2013;214:339–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alijotas-Reig J, Fernández-Figueras MT, Puig L. Inflammatory, immune-mediated adverse reactions related to soft tissue dermal fillers. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43:241–58. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramzi AA, Kassim M, George JV, Amin A. Dental procedures: Is it a risk factor for injectable dermal fillers? J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(Suppl 1):158–60. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0398-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talbot SG, Parrett BM, Yaremchuk MJ. Sepsis after autologous fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:162e–164e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sykes JM, Tapias V, Pu LL. Autologous fat grafting viability: lower third of the face. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26:376–84. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taupin A, Labbé D, Nicolas J, Debout C, Benateau H. Lipofilling and weight gain. Case report and review of the literature. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2010;55:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delay E, Garson S, Tousson G, Sinna R. Fat injection to the breast: technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:360–376. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teimourian B. Blindness following fat injections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dreizen NG, Framm L. Sudden unilateral visual loss after autologous fat injection into the glabellar area. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:85–87. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egido JA, Arroyo R, Marcos A, Jiménez-Alfaro I. Middle cerebral artery embolism and unilateral visual loss after autologous fat injection into the glabellar area. Stroke. 1993;24:615–616. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feinendegen DL, Baumgartner RW, Vuadens P, Schroth G, Mattle HP, Regli F, Tschopp H. Autologous fat injection for soft tissue augmentation in the face: a safe procedure? Aesthet Plast Surg. 1998;22:163–167. doi: 10.1007/s002669900185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassetto F, Turra G, Salmaso R, Lancerotto L, Del Vecchio DA. Autologus injectable dermis: a clinical and histological study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:589.e–596.e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318282770c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sclafani AP, Romo T, 3rd, Jacono AA, McCormick S, Cocker R, Parker A. Evaluation of acellular dermal graft in sheet (AlloDerm) and injectable (micronized AlloDerm) forms for soft tissue augmentation: Clinicl observations and histologic analysis. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2:130–6. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.2.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Coninck A. Personal Communication. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, Zimmermann US, Kutzner H, Cerroni L. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tutrone WD, Cohen JL. Dissolving collagen fillers: Enzymatic degradation of some problematic filler circumstances may now include collagens. J Drug Dermatol. 2009;8:1140–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.André P. Evaluation of the safety of a non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA — Q-Medical, Sweden) in European countries: A retrospective study from 1997 to 2001. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:422–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigues-Barata AR, Camacho-Martínez FM. Undesirable effects after treatment with dermal fillers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:e59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buntrock H, Reuther T, Prager W, Kerscher M. Efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction of a monophasic cohesive polydensified matrix versus a biphasic nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid filler afer single injection in nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1097–105. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Micheels P. Human anti-hyaluronic acid antibodies: Is it possible? Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:185–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lupton JR, Altster TS. Cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid gel. Dermatol Surg. 2002;26:135–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altman RD, Moskowitz R. Intraarticular sodium haluronate (Hyalgan) in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized clinical trial. Hyalgan Study Group. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:2203–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calvo M, Tornero P, De Barrio M, Mínguez G, Infante S, Herrero T, et al. Erythema multiforme due to hyaluronic acid (go-on) J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007;17:127–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermtol Surg. 2005;31:893–7. doi: 10.1097/00042728-200508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bachmann F, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, Wiest L, Rzany B. The spectrum of adverse reactions after treatment with injectable fillers in the glabellar region: Results from the Injectable Filler Safety Study. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(Suppl 2):1629–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haneke E. Adverse effects of fillers and their histopathology. Fac Plast Surg. 2014;30:599–614. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuller-Petrović S, Pavlović MD, Schuller SS, Schuller-Lukić B, Neuhold N. Early granulomatous foreign body reactions to a novel alginate dermal filler: The system's failure? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:121–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eppley BL, Summerlin DJ, Prevel CD, Sadove AM. Effects of a positively charged biomaterial for dermal and subcutaneous augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1994;18:413–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00451350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Massone C, Horn M, Kerl H, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Giovanna Brunasso AM, Cerroni L. Foreign body granuloma due to Matridex injection for cosmetic purposes. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:197–9. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318194816d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huh SY, Cho SY, Kim KH, An JS, Won CH, Chang SE, et al. A case of complication after Matridex® injection. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:81–4. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang JH, Lee SM, Won CH, Chang SE, Lee MW, Choi JH, et al. Foreign body granuloma caused by hyaluronic acid/dextranomer microsphere filler injection. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1517–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apikian M, Roberts S, Goodman GJ. Adverse reactions to polylactic acid injection in the periorbital area. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zimmermann US, Clerici TJ. The histological aspect of fillers complications. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004;23:241–50. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palm MD, Woodhall KE, Butterwick KJ, Goldman MP. Cosmetic use of poly-L-lactic cid: A retrospective study of 130 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:161–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marmur ES, Al Quran H, De Sa Earp AP, Yoo JY. A five-patient satisfaction pilot study of calcium hydroxylapatite injection for treatment of aging hands. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1978–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daines SM, Williams EF. Complications associated with injectable soft-tissue fillers: A 5-year retrospective review. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15:226–31. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2013.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daley T, Damm DD, Haden JA, Kolodychak MT. Oral lesions associated with injected hydroxyapatite cosmetic filler. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dadzie OE, Mahalingam M, Parada M, El Helou T, Philips T, Bhawan J. Adverse reactions to soft tissue fillers — A review of the histological features. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:536–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reddy KK, Brauer JA, Anolik R, Bernstein L, Brightman LA, Hale E, et al. Calcium hydroxylapatite nodule resolution after fractional carbon dioxide laser therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:634–6. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen JC, Reisacher W, Malone M, Sulica L. Severe systemic reaction from calcium hydroxylapatite vocal fold filler. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2237–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.23762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergeret-Galley C, Latouche X, Illouz YG. The value of a new filler material in corrective and cosmetic surgery: DermaLive and DermaDeep. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;25:249–55. doi: 10.1007/s002660010131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sidwell RU, Dhillon AP, Butler PE, Rustin MH. Localized granulomatous reaction to a semi-permanent hyaluronic acid and acrylic hydrogel cosmetic filler. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:630–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Angus JE, Affleck AG, Leach ICH, Millard LG. Two cases of delayed granulomatous reactions to the cosmetic filler DermaLive, a hyaluronic acid and acrylic hydrogel. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1077–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rossner M, Rossner F, Bachmann F, Wiest L, Rzany B. Risk of sereve adverse reactions to an injectable filler based on a fixed combination of hydroxyethylmethacrylate and ethyl methacrylate with hyaluronic acid. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(Suppl 1):367–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.González-Vela MC, Armesto S, González-López MA, Fernández-Llaca JH, Val-Bernal JF. Perioral granulomatous reaction to Dermalive. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:986–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gamo R, Pinedo F, Vicente J, Naz E, Calzado L, Ruiz-Genao D, et al. Keratoacanthoma-like reaction after a hyaluronic acid and acrylic hydrogel cosmetic filler. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:954–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weyand B, Menke H. Case report: Adverse granulomatous reaction (granuloma formation) and pseudomonas superinfection after lip augmentation by the new filler DermaLive®. Eur J Plast Surg. 2008;30:291–5. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christensen LH, Breiting VB, Aasted A, Jørgensen A, Kebuladze I. Long term effects of polyacrylamide hydrogel on human breast tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1883–90. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000056873.87165.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leung KM, Yeoh GP, Chan KW. Breast pathology in complications associated with polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) mammoplasty. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalantar-Hormozi A, Mozafari N, Rasti M. Adverse effects after use of polyacrylamide gel as a facial soft tissue filler. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:139–42. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reda-Lari A. Augmentation of the malar area with polyacrylamide hydrogel: Experience with more than 1300 patients. Aesth Surg J. 2008;28:131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng NX, Wang YL, Wang JH, Zhang XM, Zhong H. Complications of breast augmentation with injected hydrophilic polyacrylamide gel. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s00266-002-2052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee CJ, Kim SG, Kim L, Choi MS, Lee SI. Unfavorable findings following breast augmentation using injected polyacrylamide hydrogel. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1967–8. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000143922.64916.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zarini E, Supino R, Pratesi G, Laccabue D, Laccabue D, Tortoreto M, et al. Biocompatibility and tissue interactions of a new filler material for medial use. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:934–42. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000133425.22598.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Malik S, Mehta P, Adesanya O, Ahluwalia HS. Migrated periocular filler masquerading as arteriovenous malformation: A diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:e18–20. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31825b34db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jones DH, Carruthers A, Fitzgerald R, Sarantopoulos GP, Binder S. Late-appearing abscesses after injections of nonabsorbable hydrogel polymer for HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S193–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goldan O, Georgio I, Grabov-Nardini G, Regev E, Tessone A, Liran A, et al. Early and late complications after a nonabsorbable hydrogel polymer injection: A series of 14 patients and novel management. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lemperle G, Morhenn V, Charrier U. Human histology and persistence of various injectable filler substances for soft tissue augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27:354–67. doi: 10.1007/s00266-003-3022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoffman AS. Synthetic polymeric biomaterials. In: Gebelein CG, editor. Polymeric Materials and Artificial Organs. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1984. pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dansereau A, Hamilton D, Kavouni A, Neuhann-Lorenz C, Pollack S, Richards R, et al. A report on the safety of and satisfaction with particle-based fillers, specifically polymethylmethacrylate microspheres suspended in collagen. Cos Derm. 2008;21:151–6. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen SR, Berner CF, Busso M, Gleason MC, Hamilton D, Holmes RE, et al. ArteFill: A long-lasting injectable wrinkle filler material - summary of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration trials and a progress report on 4- to 5-year outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(Suppl):64–76S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000234873.00905.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Solomon P, Sklar M, Zener R. Facial soft tissue augmentation with Artecoll(®): A review of eight years of clinical experience in 153 patients. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:28–32. doi: 10.1177/229255031202000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Haneke E. Polymethyl methacrylate microspheres in collagen. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004;23:227–32. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu W, Chayavichitsilp P, Hata T. Extremely delayed granulomatous reaction to soft-tissue injectables (polymethyl methacrylate) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:e206–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fischer J, Metzler G, Schaller M. Cosmetic permanent fillers for soft tissue augmentagtion: A new contraindication for interferon therapies. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:507–10. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Conejo-Mir JS, Sanz Guirado S, Angel Muñoz M. Adverse granulomatous reaction to Artecoll treted by intralesional 5-fluorouracil and triamcilonoe injections. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1079–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yagima Odo ME, Mayumi Odo L, Fujimoto Nemoto NC, Cucé LC. Treatment of nodules caused by polymethacrylate. A pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1746–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kamouna B, Kazandjieva J, Balabanova M, Dourmishev L, Negentsova Z, Etugov D, et al. Oil soluble vitamins: Illegal use for lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30:635–43. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foucar E, Downing DT, Gerber WL. Sclerosing lipogranuloma of the male genitalia containing vitamin E: A comparison with classical “paraffinoma”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:103–10. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Akkus E, Iscimen A, Tasli L, Hattat H. Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nyirady P, Kelemen Z, Kiss A, Bánfi G, Borka K, Romics I. Treatment and outcome of vaseline-induced sclerosing lipogranuloma of the penis. Urology. 2008;71:1132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Al-Ansari AA, Shamsodini A, Talib RA, Gul T, Shokeir AA. Subcutaneous cod liver oil injection for penile augmentation: Review of literature and report of eight cases. Urology. 2010;75:1181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hohaus K, Bley B, Köstler E, Schönlebe J, Wollina U. Mineral oil granuloma of the penis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:585–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maxwell GP, Gingrass MK. Ultrasound-assisted lipoplasty: A clinical study of 250 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:189–204. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199801000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zocchi ML. Ultrasonic assisted lipoplasty. Technical refinements and clinical evaluations. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;23:575–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Seward AC, Meara DJ. Industrial-grade silicone injections causing intermittent bilateral malar swelling: Review of safety and efficacy of techniques and products available. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1245–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Webster RC, Fuleihan NS, Hamadan US, Gaunt IM, Smith RC. Injectable silicone: Report of 17,000 facial treatments since 1962. Am J Cosmetic Surg. 1986;3:41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benedetto AV, Lewis AT. Injecting 1000 centistoke liquid silicone with ease and precision. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:211–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zappi E, Barnett JG, Zappi M, Barnett CR. The long-term host-response to liquid silicone injected during soft tissue augmentation procedures: A microscopic appraisal. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S186–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fulton J, Caperton C. The optimal filler: Immediate and long-term results with emulsified silicone (1,000 centistokes) with cross-linked hyaluronic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1336–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eppley BL, Sidner RA, Sadove AM. Adequate preclinical testing of bioplastique injectable material? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:157–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baijens L, Speyer R, Linssen M, Ceulen R, Manni JJ. Rejection of injectable silicone “Bioplastique” used for vocal cord augmentation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:565–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging of facial fillers: Additional insights. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:E140–1. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grippaudo FR, Di Girolamo M, Mattei M, Pucci E, Grippaudo C. Diagnosis and management of dermal filler complications in the perioral region. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16:246–52. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2014.946048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.El-Halaby A, Furtado Araújo MV. Unusual radiographic finding during routine periodontal maintenance: A case report. Tex Dent J. 2014;131:297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Damrose EJ. Radiographic properties of injected calcium hydroxylapatite: Potential false positive findings on positron emission tomography. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:1394–6. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Feeney JN, Fox JJ, Akhurst T. Radiological impact of the use of calcium hydroxylapatite dermal fillers. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488–95. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Persichetti P, Palazzolo D, Tenna S, Poccia I, Abbruzzese F, Trombetta M. Dermal filler complications from unknown biomaterials: Identification by attenuated total reflectance spectroscopy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:597e–603e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182827741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eversole R, Tran K, Hansen D, Campbell J. Lip augmentation dermal filler reactions, histopathologic features. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:241–9. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0436-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Choi HJ. Pseudocyst of the neck after facial augmentation with liquid silicone injection. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:e474–5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wiest LG, Stolz W, Schroeder JA. Electron microscopic documentation of late changes in permanent fillers and clinical management of granulomas in affected patients. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(Suppl 2):1681–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reisberger EM, Landthaler M, Wiest L, Schröder J, Stolz W. Foreign body granulomas caused by polymethylmethacrylate microspheres: Successful treatment with allopurinol. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:17–20. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]