Abstract

Background

Molecular profiling has uncovered genetic subtypes of glioblastoma (GBM), including tumors with IDH1 mutations that confer increase survival and improved response to standard-of-care therapies. By mapping the genetic landscape of brain tumors in routine clinical practice, we enable rapid identification of targetable genetic alterations.

Case Presentation

A 29-year-old male presented with new onset seizures prompting neuroimaging studies, which revealed an enhancing 5 cm intra-axial lesion involving the right parietal lobe. He underwent a subtotal resection and pathologic examination revealed glioblastoma with mitoses, microvascular proliferation and necrosis. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis showed diffuse expression of GFAP, OLIG2 and SOX2 consistent with a tumor of glial lineage. Tumor cells were positive for IDH1(R132H) and negative for ATRX. Clinical targeted-exome sequencing (DFBWCC Oncopanel) identified multiple functional variants including IDH1 (p.R132H), TP53 (p.Y126_splice), ATRX (p.R1302fs*), HNF1A (p.R263H) and NF1 (p.H2592del) variants and a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion event involving NAB2 exon 3 and STAT6 exon 18. Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) further revealed a focal amplification of NAB2 and STAT6. IHC analysis demonstrated strong heterogenous STAT6 nuclear localization (in 20 % of tumor cells).

Conclusions

While NAB2:STAT6 fusions are common in solitary fibrous tumors (SFT), we report this event for the first time in a newly diagnosed, secondary-type GBM or any other non-SFT. Our study further highlights the value of comprehensive genomic analyses in identifying patient-specific targetable mutations and rearrangements.

Keywords: NAB2-STAT6, Glioblastoma, Next generation sequencing

Background

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common, primary malignant brain tumor of adults with a median survival of 15 months despite multimodal surgical, chemo and radiotherapy [1]. GBMs are characterized by infiltrating tumor cells with nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity and accompanying necrosis and/or endothelial proliferation. More recently, molecular profiling has uncovered genetic subtypes among histologically indistinguishable GBMs that confer increased survival and improved response to standard-of-care therapies. For example, tumors with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/2) mutations show prolonged survival while tumors with MGMT promoter methylation benefit from temozolomide therapy [2, 3]. Despite inclusion of clinically relevant molecular events in routine diagnostic evaluation of brain tumors, molecular testing has largely remained limited to a small number of genetic alterations linked to specific tumor subtypes (e.g., 1p/19q co-deletion in oligodendrogliomas). Such focused interrogation strategies however ignore the genetic heterogeneity of cancer and prevent screening for less common, yet clinically actionable, genetic events. Indeed, assessment of IDH1 mutation status by immunochemistry only identifies the most common IDH1 R132H alteration, while other less frequent, yet prognostically important IDH1/2 are not assessed. Furthermore, other rare genetic changes that are potentially therapeutically actionable, such as BRAF (p.V600E) mutations, are not routinely profiled in high-grade gliomas [4]. Comprehensive genomic analysis of brain tumors provides objective companion data to support and refine histologic diagnoses [5]. Furthermore, by mapping the genetic landscape of brain tumors in routine clinical practice, we enable rapid identification of targetable genetic alterations and support patient enrollment onto molecularly stratified clinical trials.

Case presentation

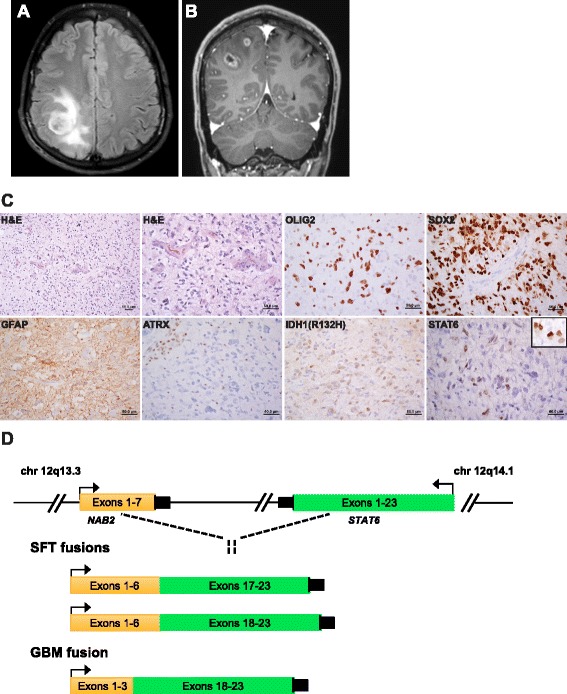

A previously healthy 29-year-old male presented to an outside hospital with a symptomatic intra-axial enhancing right parietal brain lesion necessitating surgical management and adjuvant temozolomide (Fig. 1a, b). Histology showed a densely cellular infiltrating glial neoplasm comprised of severely atypical cells with mitoses, vascular proliferation and necrosis consistent with GBM (Fig. 1c). Immunohistochemistry demonstrates tumor cells were positive for GFAP, OLIG2, SOX2, IDH1(R132H) and a MIB1 proliferation index of >30 % (Fig. 1c). MGMT methylation testing revealed that the tumor was positive for promoter methylation.

Fig. 1.

a Coronal T2 FLAIR highlights the intra-parenchymal location of the complex tumor resection bed and associated edema. b Axial post contrast T1 MRI showing peripheral ring enhancement and progression from previous post-surgical imaging (right). c H&E sections showing a hypercellular fibrillary neoplasm with morphological atypia, mitoses, and endothelial proliferation. Necrosis was also present (not shown). The tumor showed diffuse expression of the glial markers Olig2, Sox2 and GFAP. Immunoreactivity with antibody against the R132H IDH1 mutation. ATRX immunostaining highlighting loss within the tumor and normal retained expression in a adjacent vessel. Immunohistochemistry with the STAT6 antibody showing strong nuclear expression in 15–20 % of tumor nuclei (inset) consistent with previous described function of NAB2-STAT6 fusion event. d Schematic demonstrating the locations of common NAB2-STAT6 rearrangements in solitary fibrous tumor (SFTs), the presented case GBM and other STAT6 rearrangements reported in GBMs

Targeted exome sequencing (OncoPanel) of 300 cancer-associated genes and 113 introns from 35 genes for rearrangement was performed on DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor tissue [6, 7]. OncoPanel revealed IDH1 (p.R132H), TP53 (p.Y126_splice), ATRX (p.R1302fs*), HNF1A (p.R263H) and NF1 (p.H2592del) variants, several variants of unknown significance, and a NAB2-STAT6 fusion involving exon 3 of NAB2 and exon 18 of STAT6 (Fig. 1d, Table 1). This rearrangement has not previously been reported outside the context of solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs). In SFTs, fusion products are variable, but typically involve exons 6/7 of NAB2 and exons 17/18 of STAT6 [8] (Fig. 1d). Similar to the functional consequence of this fusion product in SFTs, we confirmed that this novel NAB2-STAT6 fusion detected in our GBM patient resulted in strong STAT6 nuclear localization [9] (Santa Cruz, catalog #sc-621), however this was present in only a subpopulation of cells (Fig. 1c).

Table 1.

Mutations identified in GBM patient by targeted exome sequencing (OncoPanel)

| Gene Symbol | Protein Change | Allelic Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| IDH1 | p.R132H | 0.50 |

| TP53 | p.Y126_splice | 0.85 |

| ATRX | p.R1302fs | 0.46 |

| HNF1A | p.R263H | 0.16 |

| NF1 | p.H2592del | 0.38 |

| GLI1 | p.G798R | 0.73 |

| MLH1 | p.R389Q | 0.46 |

| MLL2 | p.Q4557_splice | 0.36 |

To determine whether this event might be recurrent in gliomas, and given multiple genomic alterations detected in this tumor closely resemble those found in adult low-grade gliomas (ALGGs) (mutations in IDH1, TP53 and ATRX) [10], we investigated the frequency of NAB2-STAT6 fusions in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) low-grade glioma database (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). This analysis included 50 tumors with whole genome sequencing (WGS) and 311 tumors with whole exome sequences (WES). Among this 361 patient cohort, we did not detect any evidence of NAB2-STAT6 fusions, nor fusion events involving NAB2 or STAT6 with other fusion partners.

We next analyzed TCGA adult GBM datasets including 42 and 164 tumors tested by WGS and RNA sequencing, respectively. Similar to our findings among ALGGs, we did not detect NAB2-STAT6 fusions but did identify two unique STAT6 fusion events STAT6-CPM and HIPK2-STAT6 and each co-amplified with oncogenes CDK4 and MDM2 in the amplicon on chromosome 12q13-15. These observations suggest that STAT6 fusions occur at a low frequency but may be recurrent with other 12q13-15 amplification events.

Given this finding, we performed genome wide array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), or copy number analysis, of our case study GBM and also identified co-amplification of NAB2, STAT6 and CDK4 involving a 12q3-14 amplicon of 0.6 Mb (Table 2).

Table 2.

aCGH copy number alterations identified in GBM patient

| Gene/Region | Chromosome Band | Copy Number Change | Nucleotides (GRCh37//hg19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYCL1 | 1p34.2 | -- | -- |

| CDKN2C | 1p33 | -- | -- |

| PIK3C2B | 1q32.1 | -- | |

| MDM4 | 1q32.1 | -- | -- |

| AKT3 | 1q44 | -- | |

| MYCN | 2p24.3 | -- | -- |

| PIK3CA | 3q26.32 | -- | |

| SOX2 | 3q26.33 | -- | -- |

| FGFR3 | 4p16.3 | -- | |

| PDGFRA | 4q12 | 550 kb focal gain | chr4:55,072,465–55,622,596 |

| TERT | 5p15.33 | -- | |

| MYB | 6q23.3 | -- | -- |

| PARK2 | 6q26 | -- | |

| QKI | 6q26 | -- | -- |

| EGFR | 7p11.2 | -- | |

| EGFRvIII | 7p11.2 | -- | -- |

| CDK6 | 7q21.2 | -- | |

| MET | 7q31.2 | -- | -- |

| BRAF | 7q34 | -- | |

| FGFR1 | 8p11 23-p11.22 | -- | -- |

| MYBL1 | 8q13.1 | -- | |

| MYC | 8q24.21 | -- | -- |

| CDKN2A | 9p21.3 | 38.5 Mb single copy gain | chr9:204,104–38,731,432 |

| NTRK2 | 9q21.32-q21.33 | 1.3 Mb focal gain | chr9:86,840,129–88,134,100 |

| NTRK2 | 9q21.32-q21.33 | 159 kb intragenic amplification | chr9:87,344,078–87,503,027 |

| PTEN | 10q23.31 | 82.6 Mb single copy loss | chr10:52,805,936–135,435,714 |

| FGFR2 | 10q26.13 | 82.6 Mb single copy loss | chr10:52,805,936–135,435,714 |

| CCND2 | 12p13.32 | 34.6 Mb single copy loss | chr12:163,593–34,756,209 |

| NAB2 | 12q13.3 | 37 kb amplification | chr12:57,484,461 –57,521,151 |

| STAT6 | 12q13.3 | 37 kb amplification | chr12:57,484,461 –57,521,151 |

| CDK4 | 12q14.1 | 131 kb amplification | chr12:58,034,214–58,165,540 |

| MDM2 | 12q15 | 95.3 Mb single copy loss | chr12:38,448,667–133,779,076 |

| RB1 | 13q14.2 | Single copy loss via monosomy 13 | chr13:19,296,544–115,105,297 |

| TP53 | 17p13.1 | 19.5 Mb single copy loss | chr17:47,546–19,536,368 |

| NF1 | 17q11.2 | -- | |

| SMARCB1/INI1 | 22q11.23 | Single copy loss via monosomy 22 | chr22:16,133,474–51,219,009 |

| NF2 | 22q12.2 | Single copy loss via monosomy 22 | chr22:16,133,474–51,219,009 |

| 1p- | n/a | -- | -- |

| 4p- | n/a | -- | |

| Monosomy 6 | n/a | -- | |

| 6q- | n/a | -- | |

| Polysomy 7 | n/a | -- | |

| 7p- | n/a | -- | |

| Monosomy 10 | n/a | -- | |

| 10q- | n/a | 82.6 Mb single copy loss | chr10:52,805,936–135,435,714 |

| 11p- | n/a | -- | -- |

| Monosomy 14 | n/a | -- | |

| idic(17p11.2) | n/a | -- | |

| 18q- | n/a | -- | |

| 19q- | n/a | -- | |

| Monosomy 22 | n/a | Detected | chr22:16,133,474–51,219,009 |

Conclusions

Incorporating molecular analyses into current diagnostic pipelines for GBM patients may provide an avenue for identifying novel aberrations or events that have been previously reported in other tumor types [7]. One study reported that such a genome wide screening strategy can in fact yield candidate actionable genetic alterations in every case analysed [6]. Here we demonstrate that targeted-exome sequencing of a GBM revealed a NAB2-STAT6 fusion, which is a known oncogenic driver in SFTs but has not been reported in other cancers. In SFTs, the novel fusion product results in nuclear translocation of the STAT6 transcriptional activating domain and activation of the early growth response (EGR1) pathway leading to tumorigensis [8, 11]. The strong nuclear STAT6 staining in a subpopulation of GBM cells parallels what is found in SFTs, suggesting a similar mechanism of action. Given its high frequency in SFTs, the NAB2-STAT6 fusion has raised interest as both a diagnostic and potentially druggable therapeutic target [12]. Although the frequency of this event has not been fully explored, our results from querying TCGA ALGG and GBM datasets demonstrates that specific NAB2-STAT6 fusion events are rare in gliomas but that STAT6 fusions are recurrent events with several partners in adult GBM. Despite the low recurrence frequency, this fusion supports repurposing drugs developed against the NAB2-STAT6 or the EGR pathway in SFTs as a potential alternative or adjuvant therapy for patients with genetically similar gliomas.

Interestingly, similar to other STAT6 rearrangement events in GBMs, we noted CDK4 amplification in this patient. Chromosome 12 is frequently subject to a storm of amplification/rearrangement events in GBMs, including CDK4, MDM2, and HMGA2 amplifications as well as other regions (including KRAS). These events suggest a more complex rearrangement involving much of the chromosome and are reminiscent of ring chromosomes found in dedifferentiated liposarcomas [13–15]. Given the genetic proximity of CDK4 and MDM2 to STAT6 and NAB2 in the chromosomal region 12q13-15, the fusion product may represent a consequence of this more complex rearrangement. Understanding the precise functional consequences of this molecular alteration in glioma biology will be important to guiding future therapies of similar cases [13]. As genome wide sequencing strategies become more widely available in the clinical setting, infrequent mutations and/or rare fusion events may collectively represent a brain tumor patient population that can be managed with targeted therapies approved for use in other tumor types. This strategy may pave the way for improving outcomes in a small subset of GBM patients.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained for 10–417 and 11–104 (OncoPanel) from the patient for sequencing analysis, publication of this report and accompanying images.

Abbreviations

- aCGH

array comparative genomic hybridization

- ALGG

adult low grade glioma

- EGR1

early growth response

- GBM

glioblastoma

- SFT

solitary fibrous tumor

- TCGA

the cancer genome atlas

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PD, RYH, PYW contributed clinical, oncology and radiology data, generated figures and provided written text for the manuscript. PD, RDF, KLL, SHR performed pathologic analysis and initiated targeted exome sequencing. AHL, RDF, KLL, SHR were responsible for the array CGH and sequencing analyses. RFL and RB analyzed TCGA datasets and contributed content to the written text. PD and SHR wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Phedias Diamandis, Email: p.diamandis@mail.utoronto.ca.

Ruben Ferrer-Luna, Email: rferrer@broadinstitute.org.

Raymond Y. Huang, Email: ryhuang@partners.org

Rebecca D. Folkerth, Email: rfolkerth@partners.org

Azra H. Ligon, Email: aligon@partners.org

Patrick Y. Wen, Email: Patrick_Wen@dfci.harvard.edu

Rameen Beroukhim, Email: Rameen_Beroukhim@dfci.harvard.edu.

Keith L. Ligon, Email: Keith_Ligon@dfci.harvard.edu

Shakti H. Ramkissoon, Phone: 617-582-8767, Email: sramkissoon@partners.org

References

- 1.Johnson DR, O’Neill BP. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J Neurooncol. 2012;107:359–64. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0749-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann C, Hentschel B, Wick W, Capper D, Felsberg J, Simon M, et al. Patients with IDH1 wild type anaplastic astrocytomas exhibit worse prognosis than IDH1-mutated glioblastomas, and IDH1 mutation status accounts for the unfavorable prognostic effect of higher age: implications for classification of gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:707–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegi ME, Diserens A-C, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dias-Santagata D, Lam Q, Vernovsky K, Vena N, Lennerz JK, Borger DR, et al. BRAF V600E mutations are common in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Brat DJ, Verhaak RGW, Aldape KD, Yung WK, Salama SR, et al. Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2481–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagle N, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Pochanard P, et al. High-throughput detection of actionable genomic alterations in clinical tumor samples by targeted, massively parallel sequencing. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:82–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramkissoon SH, Bi WL, Schumacher SE, Ramkissoon LA, Haidar S, Knoff D, et al. Clinical implementation of integrated whole-genome copy number and mutation profiling for glioblastoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2015;17:1344–1355. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson DR, Wu Y-M, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Cao X, Lonigro RJ, Sung YS, et al. Identification of recurrent NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:180–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schweizer L, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Piro RM, Capper D, Reuss DE, et al. Meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors carry the NAB2-STAT6 fusion and can be diagnosed by nuclear expression of STAT6 protein. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:651–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cryan JB, Haidar S, Ramkissoon LA, Bi WL, Knoff DS, Schultz N, et al. Clinical multiplexed exome sequencing distinguishes adult oligodendroglial neoplasms from astrocytic and mixed lineage gliomas. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8083–92. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M, O’Connor R, Walker SR, Ambrogio L, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:131–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frith AE, Hirbe AC, Van Tine BA. Novel pathways and molecular targets for the treatment of sarcoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15:378–85. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah N, Lankerovich M, Lee H, Yoon JG, Schroeder B, Foltz G. Exploration of the gene fusion landscape of glioblastoma using transcriptome sequencing and copy number data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:818. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weaver J, Downs-Kelly E, Goldblum JR, Turner S, Kulkarni S, Tubbs RR, Rubin BP, Skacel M. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for MDM2 gene amplification as a diagnostic tool in lipomatous neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(8):943–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]