Abstract

Background

Thionins are a family of plant antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), which participate in plant defense system against pathogens. Here we describe some aspects of the CaThi thionin-like action mechanism, previously isolated from Capsicum annuum fruits. Thionin-like peptide was submitted to antimicrobial activity assays against Candida species for IC50 determination and synergism with fluconazole evaluation. Viability and plasma membrane permeabilization assays, induction of intracellular ROS production analysis and CaThi localization in yeast cells were also investigated.

Results

CaThi had strong antimicrobial activity against six tested pathogenic Candida species, with IC50 ranging from 10 to 40 μg.mL−1. CaThi antimicrobial activity on Candida species was candidacidal. Moreover, CaThi caused plasma membrane permeabilization in all yeasts tested and induces oxidative stresses only in Candida tropicalis. CaThi was intracellularly localized in C. albicans and C. tropicalis, however localized in nuclei in C. tropicalis, suggesting a possible nuclear target. CaThi performed synergistically with fluconazole inhibiting all tested yeasts, reaching 100 % inhibition in C. parapsilosis. The inhibiting concentrations for the synergic pair ranged from 1.3 to 4.0 times below CaThi IC50 and from zero to 2.0 times below fluconazole IC50.

Conclusion

The results reported herein may ultimately contribute to future efforts aiming to employ this plant-derived AMP as a new therapeutic substance against yeasts.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptides, Thionin, Synergistic activity, Fluconazole, Candida

Background

Currently, a significant global public health threat is the emergence of pathogenic bacteria, fungi, and yeasts that are resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents. Indeed, few or no effective chemotherapies are available for infections caused by some of these resistant microorganisms [1, 2].

Alternatives to chemotherapies include antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), small molecules produced by all living organisms, which have gained considerable attention because of their potent antimicrobial activity against a broad range of microbes, including viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi [3, 4]. Moreover, some kill microorganisms rapidly, are able to synergize with other AMPs and clinical antibiotics, have low toxicity to mammalian cells, and exert their microbial inhibitory activity at low concentrations. These molecules have multiple targets in the plasma membrane and also in intracellular components, which is thought to make an increase in microbial resistance more difficult [2, 5].

Promising AMPs include plant-derived thionins, a family of basic, low molecular weight (~5 kDa), cysteine-rich peptides. Various family members have high sequence similarity and structure [6–8]. Many of them are toxic against yeasts, pathogenic fungi, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, protozoa, and insects [7–10]. Like other AMPS, thionins’ antimicrobial activity relies on their interaction with phospholipids to cause membrane instability [10].

Infections caused by Candida species have increased substantially over the last 30 years due to the rise of AIDS, ageing population, numbers of immunocompromised patients and the extensive use of indwelling prosthetic devices [1, 11]. Candida albicans is the main cause of candidiasis, however, other Candida species such as C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata are now frequently identified as human pathogens [11–13]. Antifungals, especially fluconazole (FLC), have been used with some success for the treatment of Candida infections; however, there are numerous reports on the emergence of strains resistant to azoles that overexpress multidrug efflux transporters [14, 15].

In a previous report [8], our research team isolated a plant-derived thionin, named CaThi, with strong antimicrobial activity against two pathogenic Candida species, as well as Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FLC in combination with AMPs resulting in promising therapeutic results against important human pathogens, such as C. albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans, has been demonstrated [16, 17]. In this work we investigated whether the AMP CaThi could act synergistically with FLC. This synergistic strategy could result in a more efficient response against six Candida strains of clinical importance, avoiding the cytotoxic effects commonly exhibited by thionins against mammalian cells [10] by using low concentrations of this AMP. We were also interested in understanding the mechanism by which plant-derived thionins affect Candida species, which remains partially unknown [10]. These questions are addressed in the present study.

The results reported herein may ultimately contribute to future efforts aiming to develop this plant-derived AMP as a new therapeutic substance against these pathogenic Candida species as well as other yeast infections.

Results

Determination of IC50 for CaThi and FLC

Initially we performed growth inhibition assays of six Candida species using different concentrations of FLC and thionin CaThi to determine the IC50 of these substances. The lowest IC50 for FLC was found for C. buinensis (0.125 μg.mL−1) and the highest for C. pelliculosa (5 μg.mL- 1). In the case of CaThi, 10 μg.mL−1 was sufficient to cause 50 % inhibition of growth of C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. buinensis but 40 μg.mL−1 was necessary to achieve IC50 for C. pelliculosa. Thus, higher concentrations of both FLC and CaThi were needed to affect the growth of C. pelliculosa. Moreover, although the antimicrobial activity of CaThi against Candida species is indeed relevant, our data showed it to be lower than that observed for FLC (Table 1).

Table 1.

IC50 a (μg.mL−1) of fluconazole and CaThi in different species of Candida respectively

| Yeasts | Fluconazole | CaThi |

|---|---|---|

| Candida albicans (CE022) | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| Candida tropicalis (CE017) | 1.0 | 10.0 |

| Candida parapsilosis (CE002) | 0.5 | 10.0 |

| Candida pelliculosa (3974) | 5.0 | 40.0 |

| Candida buinensis (3982) | 0.125 | 10.0 |

| Candida mogii (4674) | 2.5 | 20.0 |

a represents the concentration of a drug that is required for 50 % inhibition in vitro

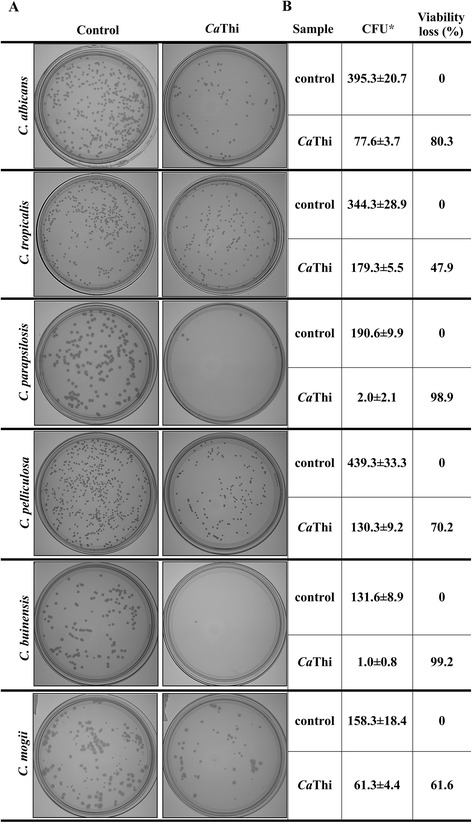

Viability assay

CaThi induced viability loss in all yeasts cells tested (Fig. 1a). The most susceptible species to CaThi were C. buinensis, C. parapsilosis and C. albicans with 99.2, 98.9 and 80.3 % of viability loss, respectively, and the less susceptible was C. tropicalis with 47.9 % of viability loss (Fig. 1b). These results indicated that inhibitory effect of CaThi was candidacidal.

Fig. 1.

Cell viability loss. a Photographs of the Petri dishes showing the viability of yeasts cells after the treatment with IC50 CaThi for 24 h. b The table shows the percentage of viability loss of yeasts cells after the treatment with IC50 CaThi for 24 h. CFU = Colony forming unit. (*) Indicates significance by the T test (P < 0.05) among the experiments and their respective controls. The experiments were carried out in triplicate

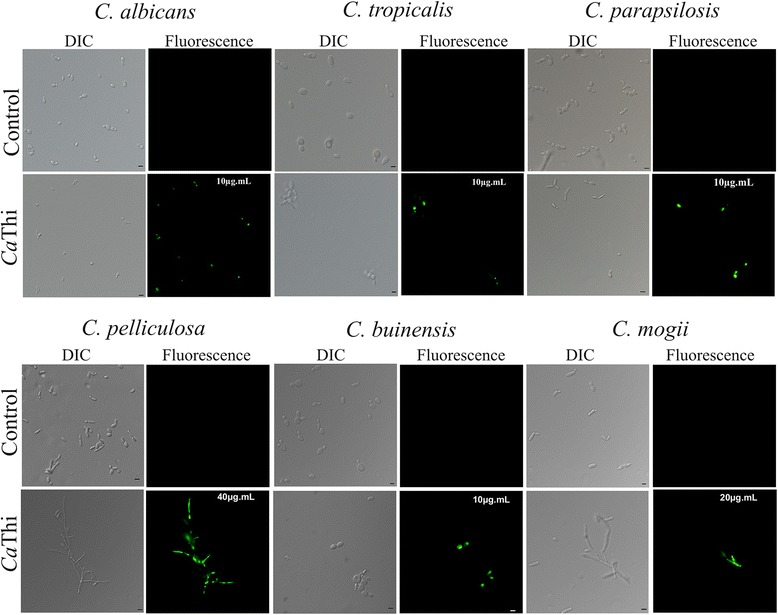

Plasma membrane permeabilization

Candida species cells were tested to determine the membrane permeabilization by Sytox green dye. All yeasts showed Sytox green fluorescence when grown for 24 h in the presence of CaThi IC50. As with other AMPs, it is likely that CaThi acts on the plasma membrane of these Candida species, compromising it structurally and allowing the permeabilization of the labeling dye (Fig. 2). The membrane permeabilization percentage of the treated yeasts with CaThi was assessed (Table 2). A higher number of C. albicans and C. pelliculosa cells presented higher Sytox green fluorescence percentage, suggesting that CaThi is more effective at permeabilizing the membrane of these cells than the other Candida species analyzed.

Fig. 2.

Membrane permeabilization assay. Photomicrography of different yeast cells after membrane permeabilization assay by fluorescence microscopy using the fluorescent probe Sytox green. Cells were treated with CaThi for 24 h and then assayed for membrane permeabilization. Control cells were treated only with probe Sytox green. Bars 5 μm

Table 2.

Fluorescent cell percentage of yeasts treated with CaThia

| Yeasts species | Sample | Cell number viewed in DIC | Cell number viewed in fluorescence | % of fluorescence cellsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | control | 62.0 ± 9.3 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.9 |

| CaThi | 20.0 ± 5.0 | 16.6 ± 5.3 | 83.0 | |

| C. tropicalis | control | 41.2 ± 4.2 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.9 |

| CaThi | 9.8 ± 4.9 | 4.8 ± 4.6 | 48.9 | |

| C. parapsilosis | control | 79.2 ± 12.1 | 0 | 0 |

| CaThi | 18.2 ± 5.4 | 6.2 ± 1.4 | 34.0 | |

| C. pelliculosa | control | 23.8 ± 3.5 | 0 | 0 |

| CaThi | 7.2 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 2.3 | 91.6 | |

| C. buinensis | control | 43.6 ± 9.0 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CaThi | 13.6 ± 6.2 | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 45.5 | |

| C. mogii | control | 18.6 ± 3.2 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 3.2 |

| CaThi | 8.6 ± 2.0 | 4.4 ± 2.7 | 51.1 |

aCells number determination in five random fields of the DIC and fluorescence views of the samples obtained from Plasma membrane permeabilization assay. The total cell number in DIC of each yeast (in control and test) was assumed as 100 %

bIndicates significance by the T test (P < 0.05) among the experiments and their respective controls

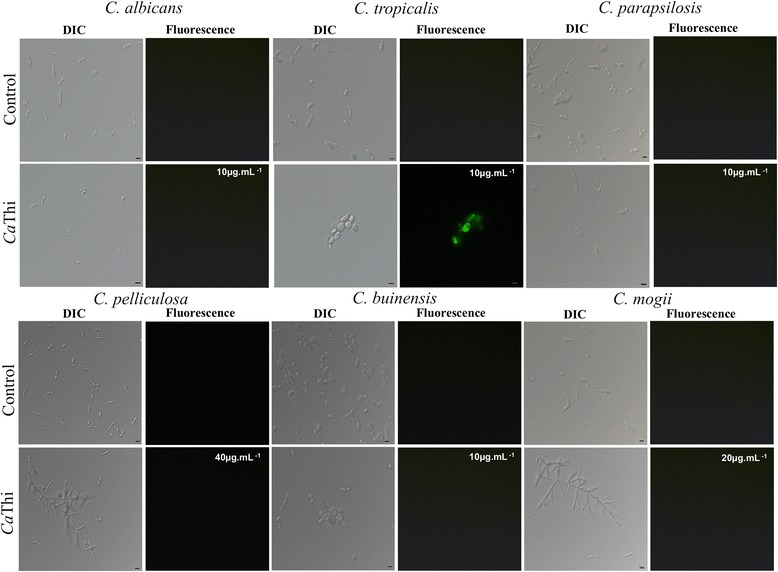

ROS induction assay

Endogenous production of ROS was analyzed by incubating the yeasts for 24 h with CaThi IC50. Increased ROS production was observed only in C. tropicalis (Fig. 3), suggesting that a CaThi-induced increase in oxidative stress may underlie the growth inhibitory effect on this yeast. Nevertheless, oxidative stresses were not detected for other Candida species, implicating that we could not associate the CaThi role and ROS production with growth inhibition of Candida, at least for the concentrations tested.

Fig. 3.

Oxidative stress assay. Photomicrography of different yeast cells after reactive oxygen species assay detection by fluorescence microscopy using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′ dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA). Cells were treated with CaThi for 24 h and then assayed for ROS detection. Control cells were treated only with probe (H2DCFDA). Bars 5 μm

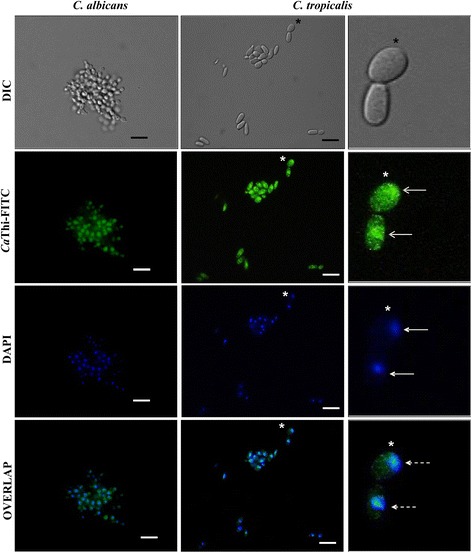

Localization of CaThi in yeast cells

We also investigated whether CaThi was actually internalized in C. albicans and C. tropicalis cells. These yeasts were chosen because they are known to be the most opportunistic pathogens among Candida species. Another important point is that C. tropicalis was the only yeast that presented membrane permeabilization and induction of ROS by CaThi in this work. To perform the test, we used 10 μg.mL−1 of FITC-tagged CaThi to search for intracellular signal fluorescence. We also treated the cells with DAPI for nuclei labeling. Intracellular signal fluorescence of CaThi-FITC was observed in both of these Candida species. However, while CaThi-FITC labeling of C. tropicalis produced a specific and intense spot of fluorescence inside the cells, C. albicans cells showed a more diffuse fluorescence. Overlapping of these CaThi-FITC images with DAPI nuclei labeling indicated a co-localization of these fluorescent signals in C. tropicalis but not in C. albicans cells (Fig. 4). These data suggest that, at least for C. tropicalis, CaThi may have an intracellular target, possibly located in the nucleus.

Fig. 4.

Localization of CaThi in yeast cells. Photomicrography of Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis cells incubated for 24 h with 10 μg.mL−1 CaThi-FITC (green fluorescence, open arrows) by fluorescence microscopy. Nuclei were visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) after the CaThi-FITC incubation period (blue fluorescence, filled arrows). Overlap of the DAPI and FITC images (dotted arrows). Bars 20 μm. (*) Indicates the position of digital enlargement

Synergism assay

Given the increase in Candida infections, particularly among immunocompromised patients, searches for antifungal therapeutic alternatives are warranted. This concern and the aforementioned data prompted us to investigate whether FLC and CaThi could act synergistically to improve therapeutic results against Candida species. The combination of FLC and CaThi showed an increase in inhibitory activity of all of the Candida species tested, suggestive of synergistic activity (Table 3). Interestingly, although C. pelliculosa had the highest IC50 for both substances, when we combined FLC at one-fold below its IC50 and CaThi at threefold below its IC50, we observed 57 % increase in growth inhibition of this yeast. Similarly, in C. parapsilosis cells, when IC50 FLC was combined with CaThi threefold below its IC50, we obtained 100 % growth inhibition of this yeast. Combined use of FLC and CaThi also strongly inhibited (96 %) C. tropicalis, although when used separately the inhibition achieved with these substances did not reach 12 %. Taken together, these data suggest that in combination FLC and CaThi could have an important synergistic action resulting in very effective control of Candida species.

Table 3.

Inhibition percentage of yeast species treated with CaThi and FLC alone and in combination showing synergism effect in vitro

| Yeasts species | Sample | Concentration (μg.mL−1)a | Inhibition (%) | Combination inhibition (%) (CaThi + FLC)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | CaThi | 3.5 | 2.93 | 77.5 |

| FLC | 0.5 | 24.48 | ||

| C. tropicalis | CaThi | 3.5 | 0 | 96.26 |

| FLC | 0.5 | 11.55 | ||

| C. parapsilosis | CaThi | 3.5 | 4.0 | 100.0 |

| FLC | 0.5 | 50 | ||

| C. pelliculosa | CaThi | 15.0 | 2.63 | 57.45 |

| FLC | 2.5 | 7.8 | ||

| C. buinensis | CaThi | 5.0 | 19.0 | 67.01 |

| FLC | 0.06 | 5.45 | ||

| C. mogii | CaThi | 10.0 | 17.19 | 61.05 |

| FLC | 1.0 | 22.80 |

a CaThi concentrations ranging 1.3 to 4.0 times below it IC50 and FLC concentrations 2.0 times below it IC50 or at it IC50

bIndicates significance by the ANOVA test (P < 0.05) which were calculated by the absorbance values of synergism among the experiments and their respective controls

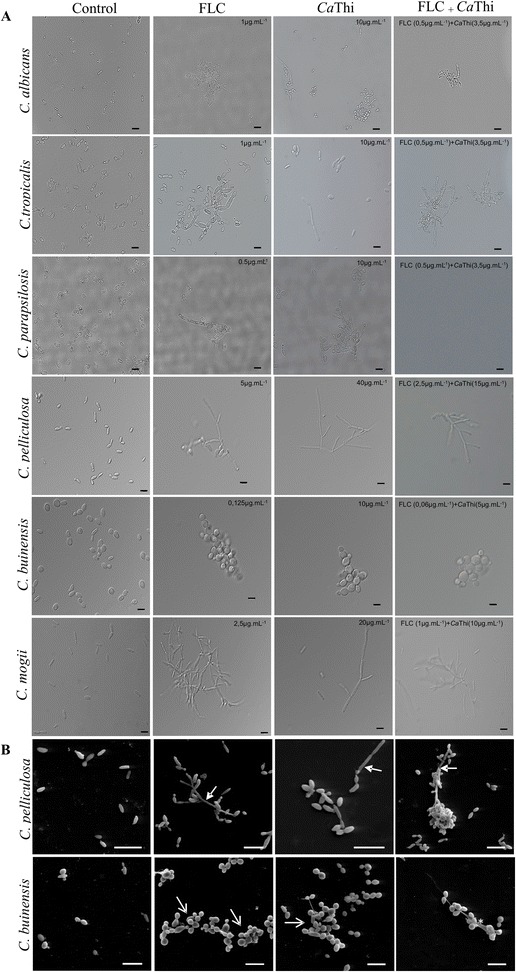

Morphological alterations of CaThi and FLC plus CaThi on yeast growth

Investigation regarding the possible morphological alterations in yeast cells grown in the presence of FLC, CaThi, or a combination of both substances after the inhibition assays (Fig. 5a) was performed. Optical microscopy analysis revealed that FLC, CaThi, and the combined treatment caused changes in the morphology of cells of Candida species. C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. pelliculosa, and C. mogii exhibited an apparent difficulty in releasing buds thus leading to the formation of pseudohyphae when grown in the presence of CaThi. Moreover, in the presence of either substance, C. tropicalis cells presented hyper branching of pseudohyphae. For C. albicans and C. buinensis, an intense cellular agglomeration in all treatments was observed. Further, the combination of CaThi and FLC caused a shrunken appearance in C. albicans cells.

Fig. 5.

Effect of CaThi, FLC, and CaThi plus FLC on yeast growth. a Photomicrography of Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida pelliculosa, Candida buinensis, and Candida mogii cells by light microscopy after the growth inhibition assay. Bars 5 μm. b Scanning electron microscopy of Candida pelliculosa and Candida buinensis. Filled arrow (formation of pseudohyphae); open arrow (cell agglomeration); asterisk (amorphous material). Bars 10 μm. Cells grown in the presence of Fluconazole (FLC), CaThi, and FLC plus CaThi

Scanning Electronic Microscopy (SEM) of C. pelliculosa reinforces the optical microscopy observations, corresponding to intense cell agglomeration and pseudohyphae formation in all treatments. For C. buinensis, all treatments showed intense cellular agglomeration and apparent difficulty in bud release, but not in the formation of pseudohyphae. For this yeast an amorphous material among cells in all treatments was also observed (Fig. 5b). These results show that CaThi is capable of causing morphological changes similar to FLC, an azole antifungal agent, commonly used in treatment of infections caused by Candida species. Importantly, we were able to demonstrate that the combination of these substances potentiates the therapeutic effects against these opportunistic species of Candida.

Discussion

Plant-derived thionins exhibit toxic effects against a wide range of plant pathogens including bacteria and fungi [18–21]. However, there is a gap regarding the mode of action of plant-derived thionins against human pathogens. Prompted by the considerable increase in the incidence of human infections by Candida species, we investigated the potential of CaThi, a plant-derived thionin peptide, as a novel therapeutic drug against six Candida strains of clinical interest: C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. pelliculosa, C. buinensis, and C. mogii.

The growth inhibition assay was not done with RPMI 1640 medium, which is generally indicated by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines, because it has in its composition a large amount of inorganic salts and it is well known in the literature that the presence of salts, such as sodium chloride and magnesium sulfate, can decrease the inhibitory activity of antimicrobial peptides since it is necessary electrostatic approximation of the peptide with the membrane of microorganisms and the presence of salts disrupts this initial interaction [22–24]. Therefore, as explained above, our growth inhibition assay was done with Sabouraud broth which is a common used medium to growth of fungi, including Candida albicans.

Our growth inhibition assays of the six Candida species tested revealed that 10 μg.mL−1 was IC50 for CaThi to inhibit the growth of C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. buinensis but 40 μg.mL−1 was necessary to achieve IC50 for C. pelliculosa (Table 1), and this inhibitory effect was candidacidal inducing viability loss in all yeast cells tested (Fig. 1). Thi 2.1, a thionin from Arabidopsis thaliana, achieved 80 % inhibition of C. albicans with 2.5 μg.mL−1 [25]. Although Thi 2.1 showed stronger antimicrobial activity against C. albicans than CaThi, these authors did not test it against non-albicans species. Thus, whether this thionin would affect other species with similar strength remains unknown.

Sytox green is a dye that only penetrates cells when the plasma membrane is structurally compromised. All yeast species tested showed Sytox green fluorescence (Fig. 2), however CaThi was more effective in plasma membrane permeabilization in C. albicans and C. pelliculosa (Table 2). Antimicrobial activity against the fungus Neurospora crassa by α-Hodothionin, isolated from barley seeds, also occurs via a mechanism involving membrane permeabilization, resulting in the inward flux of Ca2+ and K+ efflux and consequent potential membrane collapse [26]. Another plant-derived thionin isolated from Viscum album, named VtA3, interacts with the plasma membrane of the fungus Fusarium solani, causing its permeabilization and thus inhibiting the growth of this microorganism [27]. Indeed, several studies suggest that most of the biological effects of thionins result from the interaction of these peptides with the target cell membrane. Three mechanisms have been proposed: formation of an ion-selective channel; formation of patches or carpets of peptides; and loss of membrane phospholipids [10].

AMPs have been demonstrated to play a direct role in membrane permeabilization, causing a loss of membrane potential [28]. As cells depend on membrane potential to fulfill their physiological functions, its restoration is mandatory and demands cellular energy. One possible consequence of this process is ROS generation by activated mitochondria [29]. Therefore, we analyzed whether this primary membrane-permeabilizing event in Candida species induced by CaThi was followed by oxidative stress. Interestingly, CaThi only induced production of ROS in C. tropicalis (Fig. 3). We speculate that CaThi binds to a specific domain of the C. tropicalis membrane, which triggers the increase in oxidative stress response through ROS production. However, further studies are needed to establish this. Reports show that increase in ROS production by the target organisms is a recurring mode of action employed by thionins and other AMPs [27, 30, 31]. Indeed, increased death of the fungus Fusarium solani subjected to VtA3 was connected with boosted ROS production by these organisms [27]. More recently, a peptide similar to thionin isolated from the beetle Psacothea hilaris also provoked in increase in the levels of endogenous ROS in C. albicans [32]. Our study is the first to report increase in ROS production by a plant-derived thionin as an antimicrobial mechanism against a human pathogen, C. tropicalis. Therefore, CaThi seems to employ a sophisticated mechanism to inhibit the growth of this opportunistic yeast involving not only membrane permeabilization but also induction of oxidative stress response.

Some AMPs are able to enter the cell, after the initial cell membrane interaction [33, 34]. Accordingly, the next experiments were designed to analyze whether CaThi was able to actively enter C. albicans and C. tropicalis. In the approach used, FITC-tagged CaThi was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. Because CaThi entered C. albicans and C. tropicalis cells, we suggest that a possible intracellular target for this thionin might be part of a complex mechanism responsible for the death of Candida species. FITC-tagged CaThi overlapped with DAPI staining, indicating that, in C. tropicalis, this target is nuclear (Fig. 4). Giudici et al. [27] showed that VtA3 entered and accumulated in the fungus F. solani. These authors also demonstrated that this entry was related to the sphingolipid composition of the plasma membrane of this fungus. Our study is the first to show that a plant-derived thionin (CaThi) is able to enter human pathogens (C. albicans and C. tropicalis) and to suggest an intracellular target for it. Our work opens new perspectives regarding the antimicrobial mechanism of plant-derived thionins as it suggests that these peptides’ toxicity may not be restricted to the plasma membrane.

The real mode of action of AMPs has not been fully elucidated, but much of the described AMPs to date target the plasma membrane of microorganisms causing pore formation and leading to imbalance in cellular homeostasis [33, 35]. However, some studies showed that not only is permeabilization the cause of a particular microorganism death, as they may have multiple targets [36] after the interaction with the membrane causing, for example, ROS induction [31, 37]; inhibition of protein synthesis [38, 39]; inhibition of mitochondrial activity [40, 41], and also may trigger signaling cascades that lead to apoptosis [42, 43]. Thus it is difficult to identify the most important factor for the candidacidal effect of CaThi and is technically challenging to characterize the steps leading up to cell death, however evidence supports that all events described in the manuscript may have a crucial role in the death of the tested yeasts.

The continuous emergence of resistance of fungal strains to conventional antibiotics and antifungals, especially Candida species, has become an important medical issue and has spurred the demand for new therapeutic alternatives. This concern prompted us to investigate whether FLC and CaThi could act synergistically to improve therapeutic results against Candida species. Here we show that the combination of these two substances was effective against all Candida species tested (Table 3), causing drastic morphological changes in these cells (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we show that the inhibitory effect of this combination was more effective for C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis, which are the major yeast species recovered from infections in immunocompromised patients [13]. The azoles mode of action occurs by inhibition of the enzyme lanosterol 14 α-demethylase, blocking ergosterol incorporation and leading to the accumulation of intermediate sterols. These intermediate sterols do not have the same configuration and physical properties of ergosterol, therefore they cause the plasma membrane to form with altered properties, changing in fluidity, permeability and impairing nutrient uptake, which ultimately lead to cell toxicity [44, 45]. In regard to the synergistic effect of FLC and CaThi, we hypothesize that permeabilization is firstly caused by CaThi (Fig. 2) facilitating the entrance of FLC into the cell cytoplasm, triggering structural alterations in the plasma membrane which feedback positively to the entrance of more CaThi and FLC. This entrance creates potential for toxic effects, which were experimentally observed in the lower IC50 used for both substances in the combinatory treatment (Table 3). Additionally, secondary toxicity effects were demonstrated, such as the induction of ROS to C. tropicalis, the CaThi presence in C. albicans cell cytoplasm and in C. tropicalis nuclei. These localizations suggest that CaThi may have cytoplasmic targets, where interference could consolidate the inhibitory effect. However, more studies are necessary to clearly unravel the antimicrobial mechanism of CaThi against Candida species as well as the mechanism of synergy between CaThi and FLC.

Conclusions

Investigating a plant-derived thionin mode of action against opportunistic human pathogenic yeasts is relevant and advisable, whereas most studies involving plant-derived thionins focus their effects against plant pathogenic microorganisms as experimental models. In this report, we demonstrated that CaThi has strong candidacidal activity against six pathogenic Candida species, and it works by permeabilizing the membrane and inducing oxidative stress response in these yeasts. Additionally, we present evidence to suggest a nuclear intracellular target for CaThi. Finally, our results show that FLC and CaThi combined causes dramatic morphological changes in these yeasts, effective against all Candida species tested. The combined treatment of CaThi and FLC is a strong candidate for clinical studies aiming to improve therapeutic results against resistant strains of Candida species. Studies involving drug combinations should be reinforced due to the possibility of synergistic effects that increase the toxic effect of the drugs combined when compared to monotherapy. Moreover, drug combinations can broaden the spectrum of antimicrobial activity, minimizing resistant microorganisms selection, increasing security and tolerance using lower drugs doses.

Methods

Biological materials

Capsicum annuum L. fruits (accession UENF1381) were provided by Laboratório de Melhoramento Genético Vegetal, from Centro de Ciências e Tecnologias Agropecuárias, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro (UENF), Campos dos Goytacazes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The yeasts Candida albicans (CE022), Candida tropicalis (CE017), and Candida parapsilosis (CE002) were obtained from Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil. The yeasts Candida pelliculosa (3974), Candida buinensis (3982), and Candida mogii (4674) were obtained from Micoteca URM from Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. Yeasts were maintained on Sabouraud agar (1 % peptone, 2 % glucose, and 1.7 % agar-agar) (Merck) in the Laboratório de Fisiologia e Bioquímica de Microrganismos, from Centro de Biociência e Biotecnologia, UENF, Campos dos Goytacazes, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

CaThi

Extraction and purification of the thionin CaThi from Capsicum annuum fruits by chromatographic methods were performed as described by Taveira et al. [8]. The retention time to recover the thionin CaThi during the reversed-phase chromatography in column μRPC C2/C18 (ST 4.6/100) (GE Healthcare) was 37.87 min.

Preparation of yeast cells and determination of IC50 for CaThi and fluconazole

For the preparation of yeast cell cultures, an inoculum from each stock of Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida pelliculosa, Candida buinensis, and Candida mogii was transferred to Petri dishes containing Sabouraud agar and allowed to grow at 30 °C for 48 h. After this time, each cell aliquot was added to 10 mL sterile culture medium (Sabouraud broth, Merck). The cells were quantified in a Neubauer chamber (Optik Labor) with the aid of an optical microscope (Axiovison 4, Zeiss). The assay for checking the growth inhibition of yeast cells was performed according to Broekaert et al. [46] with modifications. Initially yeast cells (1 x 104 cells mL−1) were incubated in Sabouraud broth containing CaThi at concentrations ranging from 100 μg.mL−1 to 1 μg.mL−1 and fluconazole (FLC) at concentrations ranging from 20 μg.ml−1 to 0.125 μg.mL−1, with the final volume adjusted to 200 μL. The assay was performed in 96-well microplates (Nunc) at 30 °C for 24 h. Optical readings at 620 nm were recorded at zero hour and every 6 h interval for 24 h. Control cells were grown in the absence of CaThi and FLC. The optical densities were plotted against the concentration of CaThi and FLC, and then the concentration of the drug (CaThi and FLC) required for 50 % inhibition (IC50) in vitro of the tested yeasts was determined. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Viability assay

To assay the effect of CaThi on the cell viability of yeasts, 1x104 cells mL−1 in Sabouraud broth culture medium and at the corresponding IC50 of CaThi values for each yeast were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h in 96-well microplates (Nunc). To determine the control viability, the control cells (without CaThi) were washed once and diluted 1,000–fold in Sabouraud broth culture medium, and an aliquot of 100 μL from this dilution was spread over the surface of a Sabouraud agar medium (contained in a Petri dish) with a Drigalski loop and grown at 30 °C for 48 h. At the end of this period, colonies forming units (CFU) were determined for each yeast species, and the Petri dishes were photographed. The same procedure was followed with yeasts treated with CaThi. The experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the results are shown assuming that the control represents 100 % viability. Calculations of the standard deviation and T test were performed with Prism software (version 5.0).

Plasma membrane permeabilization assay

The plasma membrane permeabilization of yeast cells was measured by Sytox green uptake, according to the methodology described by Thevissen et al. [47], with some modifications. Each of the different species of yeasts was incubated with CaThi at the concentration required to inhibit 50 % growth (IC50) of the respective yeast cells for 24 h. After this time, a 100 μL aliquot of each yeast cell suspension was incubated with 0.2 μM of Sytox green in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes for 30 min at 25 °C with constant agitation. Cells were analyzed by DIC optical microscope (Axiovison 4, Zeiss) equipped with a fluorescent filter set for detection of the fluorescein (excitation wavelength, 450–490 nm, emission wavelength 500 nm). To indicate membrane permeabilization, the percentage of fluorescent cells was determined by counting the DIC and fluorescent views for each yeast (n = 5). The total cell number in DIC view of each yeast (in control and test) was assumed as 100 %. The experiments were carried out in triplicate. Calculations of T test were performed with Prism software (version 5.0).

Determining the induction of intracellular ROS in yeast cells

To evaluate whether the mechanism of action of CaThi involves induction of oxidative stress, the fluorescent probe 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) was used to measure intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) according to the methodology described by Mello et al. [31]. Each of the different species of yeasts was incubated with the respective IC50 for CaThi in 96-well microplates for 24 h at 30 °C; after this incubation an aliquot of 50 μL of each of yeast cell suspension was incubated with 200 μM of H2DCFDA in micro centrifuge tubes of 1.5 mL for 1 h at 25 °C with constant agitation at 500 rpm. Cells were analyzed by DIC optical microscope (Axiovison 4, Zeiss) equipped with a fluorescent filter set for detection of the fluorescein (excitation wavelength, 450–490 nm, emission wavelength 500 nm). The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

CaThi conjugated to FITC localization for optical microscopy

CaThi at 100 μg was resuspended in 100 μL of 750 mM sodium carbonate-sodium bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.5 containing FITC at 50 μg.mL−1 (previously solubilized in DMSO). This solution was incubated with constant agitation at 500 rpm for 2 h at 30 °C. After this incubation, the sample was submitted to gel filtration chromatography on Sephadex G25 column (Sigma) for elimination of free FITC and recovery CaThi-FITC. The column was equilibrated and run with 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0 at flow rate of 0.3 mL.mim−1. After coupling, 10 μg.mL−1 of CaThi-FITC was incubated with cells of C. albicans and C. tropicalis for 24 h in 96-well microplates. After this time an aliquot of each cell suspension was removed and incubated with 50 μg.mL−1 of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) for 10 min for nuclei stain. Cells were analyzed by DIC optical microscope (Axiovison 4, Zeiss) equipped with a fluorescent filter set for detection of the fluorescein (excitation wavelength, 450–490 nm, emission wavelength 500 nm). The entire assay was performed protected from light.

Synergism assay

To verify the synergistic activities, we combined FLC with CaThi. Initially yeast cells (1 x 104 cells mL−1) were incubated in Sabouraud broth containing an IC50 concentration or less than that for FLC and CaThi concentrations ranging from 1.3 to 4.0 times below the IC50 for the respective yeast and the final volume adjusted to 200 μL in vitro. The assay was performed in 96-well microplates (Nunc) at 30 °C for 24 h. Optical readings at 620 nm were taken at zero hour and every 6 h for the following 24 h. Control cells were: 1) grown in the absence of CaThi and FLC; 2) grown in the presence of FLC; 3) grown in the presence of CaThi. The synergistic activity was deduced comparing optical densities of each control and combined drugs (FLC plus CaThi) considering each yeast strain tested. We define synergism as the combination action of the AMP with other substance that causes an enhanced decrease in the growth of the microorganism, compared with the growth inhibition of the single substances. After synergism, assay cells (controls and tests) were analyzed by DIC optical microscope (Axiovison 4, Zeiss). The data were obtained from experiments performed in triplicate. The data were evaluated using a one-way ANOVA. Mean differences at p < 0.05 were considered to be significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0 for Windows).

Scanning electron microscopy

C. pelliculosa and C. buinensis cells were submitted to scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. Yeast cells were grown for 24 h in Sabouraud broth in the presence of FLC (5 μg.mL−1 and 0.125 μg.mL−1, respectively), CaThi (40 μg.mL−1 and 10 μg.mL−1, respectively), and FLC plus CaThi (2.5 μg.mL−1 + 15 μg.mL−1, 0.06 μg.mL−1 + 5 μg.mL−1, respectively) or absence of these drugs, then were fixed for 30 min at 30 °C in a solution containing 2.5 % glutaraldehyde and 4.0 % formaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0. Subsequently, the cells were rinsed three times in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0; post-fixed for 30 min at 30 °C with 1.0 % osmium tetroxide diluted in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0; and rinsed again with this same buffer. The yeast cells were gradually dehydrated in alcohol solution (15, 30, 50, 70 to 90 % and finally 100 % alcohol), critical point dried in CO2, covered with 20 nm gold and observed in a DSEM 962 Zeiss SEM.

Acknowledgments

This study forms part of the DSc degree thesis of GBT, carried out at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro. We acknowledge the financial support of the Brazilian agencies CNPq, FAPERJ, and CAPES through the CAPES/Toxinology project. We wish to thank L.C.D. Souza and V.M. Kokis for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AMP

Antimicrobial peptide

- FLC

Fluconazole

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- CaThi

Capsicum annuum Thionin

- DIC

Differential interference contrast

- FITC

Fluorescein isothiocyanate

- SEM

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: GBT, AOC, RR, FGT, MC and VMG. Performed the experiments: GBT and FGT. Analyzed the data: GBT, AOC, FGT, MC and VMG. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: AOC, RR, MC and VMG. Wrote the paper: GBT, AOC and VMG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Gabriel B. Taveira, Email: gabrielbtaveira@yahoo.com.br

André O. Carvalho, Email: andre@uenf.br

Rosana Rodrigues, Email: rosana@uenf.br.

Fernanda G. Trindade, Email: nanda_trindad@hotmail.com

Maura Da Cunha, Email: maurauenf@gmail.com.

Valdirene M. Gomes, Email: valmg@uenf.br

References

- 1.Pappas PG. The role of azoles in the treatment of invasive mycoses: review of the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(Suppl 2):S1–S13. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000399602.83515.ac. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avent ML, Rogers BA, Cheng AC, Paterson DL. Current use of aminoglycosides: indications, pharmacokinetics and monitoring for toxicity. Intern Med J. 2001;41:441–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–95. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guaní-Guerra E, Santos-Mendoza T, Lugo-Reyes SO, Terán LM. Antimicrobial peptides: General overview and clinical implications in human health and disease. Clinical Immunol. 2010;135:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho AO, Gomes VM. Plant defensins and defensin-like peptides - biological activities and biotechnological applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(38):4270–93. doi: 10.2174/138161211798999447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro MS, Fontes W. Plant defense and antimicrobial peptides. Protein Pept Lett. 2005;12(1):13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kido EA, Pandolfi V, Houllou-Kido LM, Andrade PP, Marcelino FC, Nepomuceno AL, et al. Plant Antimicrobial Peptides: An overview of superSAGE transcriptional profile and a functional review. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2010;11:220–30. doi: 10.2174/138920310791112110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taveira GB, Mathias LS, Vieira-da-Motta O, Machado OLT, Rodrigues R, Carvalho AO, et al. Thionin-like peptides from Capsicum annuum fruits with high activity against human pathogenic bacteria and yeasts. Biopolymers. 2014;102:30–9. doi: 10.1002/bip.22351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SC, Hong JK, Kim YJ, Hwang BK. Pepper gene enconding thionin is differentially induced by pathogens, ethilene and methyl jasmonete. Phisiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2000;56:207–16. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.2000.0269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stec B. Plant thionins – the structural perspective. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1370–85. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva S, Negri M, Henriques M, Oliveira R, Williams DW, Azeredo J. Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis: biology, epidemiology, pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. FEMS Microbiol Ver. 2012;36:288–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krcmery V, Barner AJ. Non-albicans Candida spp. causing fungaemia: pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. J Hosp Infect. 2002;4:243–60. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanglard D. Resistance of human fungal pathogens to antifungal drugs. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:379–85. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannon RD, Lamping E, Holmes AR, Niimi K, Baret PV, Keniya MV, et al. Efflux-mediated antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):291–321. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00051-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwazaki RS, Endo EH, Ueda-Nakamura T, Nakamura CV, Garcia LB, Filho BP. In vitro antifungal activity of the berberine and its synergism with fluconazole. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2010;97:201–5. doi: 10.1007/s10482-009-9394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbosa FM, Daffre S, Maldonado RA, Miranda A, Nimrichter L, Rodrigues ML. Gomesin, a peptide produced by the spider Acanthoscurria gomesiana, is a potent anticryptococcal agent that acts in synergism with fluconazole. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;274(2):279–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi DC, Muñoz JE, Carvalho DD, Belmonte R, Faintuch B, Borelli P, et al. Therapeutic use of a cationic antimicrobial peptide from the spider Acanthoscurria gomesiana in the control of experimental candidiasis. BMC Microbiology. 2012;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giudici AM, Regente MC, Villalaín J, Pfüller K, Pfüller U, De La Canal L. Mistletoe viscotoxins induce membrane permeabilization and spore death in phytopathogenic fungi. Physiol Plantarum. 2004;121:2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina A, Ahl Goy P, Fraile A, Sfinchez-Monge R, Garcia-Olmedo F. Inhibition of bacterial and fungal plant pathogens by thionins of types I and II. Plant Sci. 1993;92:169–77. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(93)90203-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandrashekhara NRS, Deepak S, Manjunath G, Shetty SH. Thionins (PR protein-13) mediate pearl millet downy mildew disease resistance. Arch Phytopathol Plant Protect. 2010;48(14):1356–66. doi: 10.1080/03235400802476393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Olmedo F, Molina A, Alamillo JM, Rodríguez-Palenzuéla P. Plant Defense Peptides. Pept Sci. 1998;47:479–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<479::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganz T, Lehrer RI. Antibiotic peptides from higher eukaryotes: biology and applications. Mol. Med. Today. 1999;5:292–7. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(99)01490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bera A, Singh S, Nagaraj R, Vaidya T. Induction of autophagic cell death in Leishmania donovani by antimicrobial peptides. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;127:23–35. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vylkova S, Nayyar N, Li W, Edgerton M. Human β-Defensins Kill Candida albicans in an Energy-Dependent and Salt-Sensitive Manner without Causing Membrane Disruption. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(1):154–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00478-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loeza-Ángeles H, Sagrero-Cisneros E, Lara-Zárate L, Villagómez-Gómez E, López-Meza JE, Ochoa-Zarzosa A. Thionin Thi2.1 from Arabidopsis thaliana expressed in endothelial cells shows antibacterial, antifungal and cytotoxic activity. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:1713–19. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9756-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thevissen K, Ghazi A, De Samblanx GW, Brownlee C, Osborn RW, Broekaert WF. Fungal membrane responses induced by plant defensins and thionins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15018–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giudici M, Poveda JA, Molina ML, De La Canal L, González-Ros JM. Antifungal effects and mechanism of action of viscotoxin A3. FEBS Journal. 2006;273:72–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dathe M, Meyer J, Beyermann M, Maul B, Hoischen C, Bienert M. General aspects of peptide selectivity towards lipid bilayers and cell membranes studied by variation of the structural parameters of amphipathic helical model peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1558:171–86. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Addabbo F, Montagnani M, Goligorsky MS. Mitochondria and Reactive Oxygen Species. Hypertension. 2009;53:885–92. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aerts AM, François IEJA, Meert EMK, Li QT, Cammue BPA, Thevissen K. The antifungal activity of Rs-AFP2, a plant defensin from Raphanus sativus, involves the induction of reactive oxygen species in Candida albicans. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;13:243–47. doi: 10.1159/000104753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mello EO, Ribeiro SFF, Carvalho AO, Santos IS, Da Cunha M, Santa Catarina C, et al. The antifungal activity of PvD1, a plant seed defensin of Phaseolus vulgaris, involves plasma membrane permeabilization, inhibition of medium acidification and induction of reactive oxygen species in yeast cells. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:1209–17. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9847-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang B, Hwang J-S, Lee J, Lee DG. The antimicrobial peptide, psacotheasin induces reactive oxygen species and triggers apoptosis in Candida albicans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405:267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–50. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolas P. Multifunctional host defense peptides: intracellular-targeting antimicrobial peptides. FEBS J. 2009;276:6483–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuzaki K, Sugishita K, Harada M, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Interactions of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, with outer and inner membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1327:119–130. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(97)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franco OL. Peptide promiscuity: An evolutionary concept for plant defense. FEBS Letters. 2011;585:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carvalho AO, Gomes VM. Plant defensins - prospects for the biological functions and biotechnological properties. Peptides. 2009;30:1007–20. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yonezawa A, Kuwahara J, Fujii N, Sugiura Y. Binding of tachyplesin I to DNA revealed by footprinting analysis: significant contribution of secondary structure to DNA binding and implication for biological action. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2998–3004. doi: 10.1021/bi00126a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boman HG, Agerberth B, Boman A. Mechanisms of action on Escherichia coli of cecropin-P1 and PR-39, 2 antibacterial peptides from pig intestine. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2978–84. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2978-2984.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helmerhorst EJ, Breeuwer P, van ‘t Hof W, Walgreen-Weterings E, Oomeni LCJM, Veerman ECI, et al. The Cellular Target of Histatin 5 on Candida albicans Is the Energized Mitochondrion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(11):7286–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vieira MEB, Vasconcelos IM, Machado OLT, Gomes VM, Carvalho AO. Isolation, characterization and mechanism of action of an antimicrobial peptide from Lecythis pisonis seeds with inhibitory activity against Candida albicans. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2015;47(9):716–29. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmv071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulkarni MM, McMaster RW, Kamysz W, McGwire BS. Antimicrobial Peptide-induced Apoptotic Death of Leishmania Results from Calcium-dependent, Caspase-independent Mitochondrial Toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(23):15496–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809079200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aerts AM, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Lefevre S, Govaert G, Francois IE, Madeo F, et al. The antifungal plant defensin RsAFP2 from radish induces apoptosis in a metacaspase independent way in Candida albicans. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2513–16. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lupetti A, Danesi R, Campa M, Del Tacca M, Kelly S. Molecular basis of resistance to azole antifungals. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:76–81. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cowen LE. The evolution of fungal drug resistance: modulating the trajectory from genotype to phenotype. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:187–98. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broekaert WF, Mariën W, Terras FR, De Bolle MF, Proost P, Van Damme J, et al. Antimicrobial peptides from Amaranthus caudatus seeds with sequence homology to the cysteine/glycine rich domain of chitin-binding proteins. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4308–14. doi: 10.1021/bi00132a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thevissen K, Terras FRG, Broekaert WF. Permeabilization of fungal membranes by plant defensins inhibits fungal growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5451–58. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5451-5458.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]