Abstract

Background

Previously, we performed a quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping study in BXD recombinant inbred mice to identify host genetic factors that confer resistance to influenza A virus infection. We found Lst1 (leukocyte specific transcript 1) as one of the most promising candidate genes in the Qivr17-2 locus because it is non-functional in DBA/2 J mice. Several studies have proposed that LST1 plays a role in the immune response to inflammatory diseases in humans and has additional immune-regulatory functions. Here, we evaluated the relevance of LST1 for the host response to influenza A infection in B6-Lst1−/− mutant mice.

Findings

To investigate the role of LST1, we infected B6-Lst1−/− mutant and C57BL/6 N wild-type mice with a low-virulent influenza A virus (PR8M; H1N1). Lst1 deficient mice exhibited significantly increased body weight loss at days 5 and 6 after infection and slightly increased lethality compared to infected wild-type mice. Determination of viral loads, histopathological examination and analysis of immune cell composition in bronchoalveolar lavage of infected lungs did not reveal any obvious differences between KO and wild-type mice.

Conclusions

The absence of Lst1 leads to a slightly more susceptible phenotype. However, deletion of Lst1 in DBA/2 J mice alone does not explain the high susceptibility of this strain to PR8M influenza infections.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12985-016-0471-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Influenza A virus, Lst1, KO mouse mutant, Animal model

Findings

Each year, about 500 million people are infected by influenza A virus worldwide, of which about 500,000 die. We and others showed that the genetic background strongly influences the course and outcome of influenza A virus infections in different mouse inbred strains [1–4]. To identify genes that influence resistance or susceptibility to influenza A infections, we performed a genome-wide quantitative mapping study using the BXD recombinant inbred strains derived from C57BL/6 J and DBA/2 J. When infected with a low virulent isolate of PR8 influenza A virus (designated PR8M), DBA/2 J mice are highly susceptible and die within 5–7 days post infection (p.i.), whereas C57BL/6 J mice survive [1, 5]. We found about 30 candidate genes across five QTL regions [2]. One of the most promising candidates in the Qivr17-2 (quantitative trait for influenza virus resistance on chromosome 17) locus was the leukocyte specific transcript 1 (Lst1). The human gene LST1 and its mouse homologue Lst1, formerly described as B144 [6], are located in the MHC class III locus encoding numerous genes involved in the immune response [7, 8]. Transcripts are most abundant in immune cells, especially B cells, T cells, monocytes and dendritic cells [9]. Lst1 expression has been shown to be up-regulated by inflammatory stimuli [8, 10]. DBA/2 J mice exhibit a deletion in the Lst1 which results in a translational frame shift that most likely causes a premature stop codon and thus results in a truncated, non-functional protein [2]. Expression of Lst1 transcripts was up-regulated in C57BL/6 J mice after infection with influenza A virus (PR8M; H1N1). Expression levels increased already at day 2 post infection (p.i.), showing a peak of expression at day 8 p.i.. At later time points Lst1 expression decreased and reached levels that were similar to non-infected mice on day 18 p.i. [2, 11]. Thus, Lst1 expression was found both during the innate and adaptive phase of the host response to influenza and peaked at the time point of T cell infiltration. Bio-GPS (http://biogps.org) expression studies show that Lst1 was mainly expressed in immune cells including mast cells, macrophages and dendritic cells.

To further characterize the role of LST1 after influenza A infection, we studied the host response in a Lst1 mouse knock-out (KO) model. The KO strain C57BL/6 N-Lst1tm1(KOMP)Vlcg was created from the ES cell clone 12118A-B1 (obtained from the KOMP Repository; www.komp.org). It harbors a reporter-tagged deletion of the Lst1 gene. We confirmed insertion of the targeting cassette into the coding region of exon two and three by PCR genotyping (Additional file 1: Figure S1A) and showed absence of transcripts in knock-out mice by reverse transcription PCR (Additional file 1: Figure S1B).

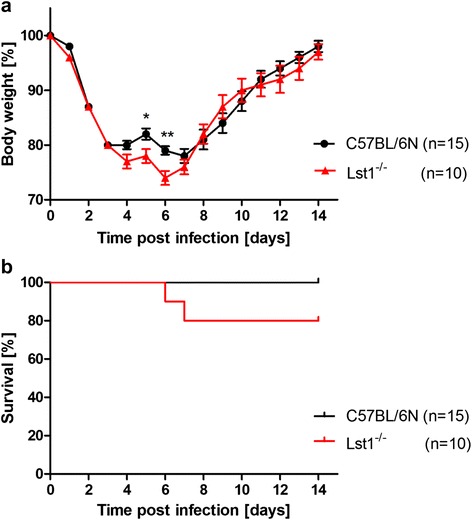

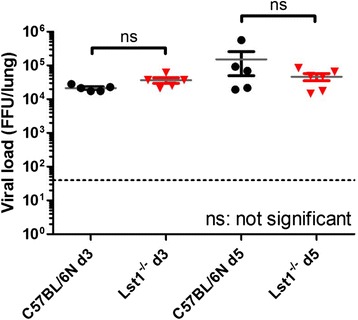

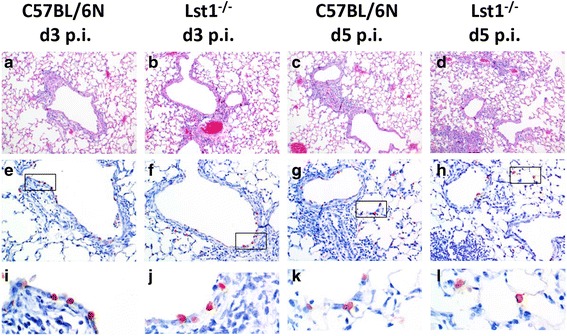

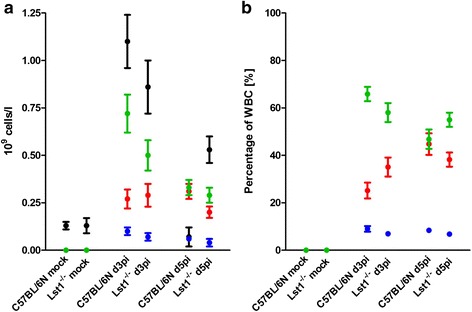

We then infected eight to twelve weeks old female C57BL/6 N-Lst1tm1(KOMP)Vlcg as well as wild type control mice (C57BL/6 N) with 2×105 focus forming units (FFU) of the low-virulent mouse-adapted A/PuertoRico/8/34 H1N1 virus (PR8M; [5]) after anesthesia with intra-peritoneal injection with a mixture of 100 mg/ml Ketamine and 20 mg/ml Xylazine. All animal experiments were approved by an external committee and according the guidelines of the animal welfare law in Germany (Permit numbers: 33.942502-04-051/09, 3392 42502-04-13/1234). Changes in body weight and survival rates were monitored for 14 days p.i. (Fig. 1). Mice with a loss of more than 30 % of the starting body weight were euthanized and recorded as dead. Lst1 KO mice exhibited significantly increased body weight loss at days 5 and 6 p.i.. All wild-type mice survived the infection with PR8M virus whereas the KO mice showed a lethality of 20 %. However, this difference in survival was not statistical significant. No difference in survival and body weight loss was observed between wildtype and Lst1 KO mice after infection with another influenza A virus subtype (A/Hong Kong/01/68 H3N2, [12], Additional file 1: Figure S2). Furthermore, comparison of viral loads [5] between lungs of PR8M infected Lst1−/− and wild-type mice at day 3 and 5 p.i. did not reveal significant differences (Fig. 2). Histopathological analysis of infected lungs showed no obvious alteration in morphology and immune cell infiltration in KO mice compared to the wild-type controls (Fig. 3). To assess the magnitude and composition of immune cell infiltrates in the airways, we analyzed bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). We were not able to detect significantly different amounts of immune cells neither in infected nor in mock-infected BAL fluids (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Lst1 KO mice revealed a slightly more susceptible phenotype in comparison to C57BL/6 N wild-type mice after infection with H1N1 influenza A virus. Female C57BL/6 N-Lst1 tm1(KOMP)Vlcg (n = 10) and wild-type C57BL/6 N mice (n = 15) were infected intra-nasally with 2×105 FFU PR8M in 20 μl PBS. Body weight (a) and survival (b) were determined for each day p.i. for a period of 14 days. Percent weight is shown with reference to the starting body weight. Significances were calculated using non-parametric Mann Whitney U test. (p < 0.05 for day 5; p < 0.01 for day 6) and Log-rank test for survival rates (not significant)

Fig. 2.

Similar viral loads in lungs of infected Lst1 KO and C57BL/6 N wild-type mice. Female C57BL/6 N-Lst1 tm1(KOMP)Vlcg (n = 5 / time point; red) and wild type (C57BL/6 N) mice (n = 5 / time point; black) were infected intra-nasally with 2 × 105 FFU PR8M in 20 μl PBS. Lung samples were taken on day 3 and 5 p.i.. Lungs were homogenized and viral load was titrated thrice for each sample. Each symbol represents one mouse. Mean values (grey) +/− SEM are depicted. Statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test; ns: not significant. The dotted line marks the detection limit

Fig. 3.

Lungs of Lst1 KO mice and C57BL/6 N wild-type mice did not show obvious histological differences after IAV challenge. Female C57BL/6 N-Lst1 tm1(KOMP)Vlcg (n = 3 / time point) and wild type (C57BL/6 N) mice (n = 3 / time point) were infected intra-nasally with 2 × 105 FFU PR8M in 20 μl PBS. Lung samples were taken on day 3 and 5 p.i.. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples were sectioned at 5 μm thickness and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or with a monoclonal antibody against the nucleoprotein of influenza A virus (anti-NP) [26]. Similar amounts of infiltrating immune cells (a-d) and similar numbers of virus-infected cells (e-h) were observed at 3 and 5 days p. i. Immuno-histochemical staining with anti-NP antibody was detected mostly in bronchiolar regions on day 3 p.i. (i and j), whereas on day 5 p.i. virus did spread further into alveolar regions in both mouse strains (k and l). A-D: Hematoxylin and eosin staining (10× magnification); e-h: anti-NP immune-histochemical staining (20× magnification); I-L: anti-NP staining (60× magnification)

Fig. 4.

No difference in the immune cell composition in bronchoalveolar lavage in Lst1 KO and C57BL/6 N wild-type control mice. Female C57BL/6 N-Lst1 tm1(KOMP)Vlcg (n = 5-6 / time point) and wild type (C57BL/6 N) mice (n = 9-10 / time point) were infected intra-nasally with 2 × 105 FFU PR8M in 20 μl PBS. On day 3 and 5 p.i. mice were euthanized by isoflurane. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was collected via instillation of 0.8 ml PBS per mouse. BAL was immediately analyzed in the hematologic system VetScan HM5 (Abaxis). Samples of mock-infected mice were collected on day 3 post PBS treatment. Absolute numbers of white blood cells (black), lymphocytes (green), granulocytes (red) and monocytes (blue) are shown in a. Lymphocyte, granulocyte and monocyte amounts relative to total white blood cells counts are depicted in b. Mean values +/− SEM are shown. Statistical analysis was performed using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test

In conclusion, B6-Lst1−/− KO mice are slightly more susceptible to PR8M influenza A infection which is reflected in an increased body weight loss and slightly reduced survival rate. The susceptibility of KO mice is much less pronounced compared to DBA/2 J mice. Thus, our results show some contribution of Lst1 to susceptibility of DBA/2 J mice. However, its effect is rather small. Therefore, other genes with polymorphisms in Qivr17-2 as well as polymorphic genes in other QTL regions are contributing to the high susceptibility of DBA/2 J mice. Furthermore, it is conceivable that Lst1 has a major contribution by interacting with additional DBA/2 J alleles in Qivr17-2 or other QTLs that were mapped previously. These results emphasize the influence of different gene loci on the host response to influenza A H1N1 infection in mice.

There are numerous reports describing that LST1 plays an important role in the immune response to inflammatory diseases in humans [10, 13–15], in bacterial infections [10] and in signal transduction [16, 17]. It has been demonstrated that LST1 plays a crucial role for transmembrane cell to cell communication [18], which was shown to be important for the intercellular transport of bacteria and retroviruses [19]. Furthermore, the expression of the Lst1 gene was shown to be up-regulated in response to lipopolysaccharide, interferon-γ and bacterial infections [10].

The LST1 gene has been studied extensively at the gene and mRNA level [20], but the biological functions of the protein product are largely unknown. Overexpression of LST1 in several human cell lines leads to the formation of filopodia-like membrane protrusions [21]. Recently, it was proposed that LST1 promotes the formation of tunneling nanotubes [18]. Interestingly, it has been shown that several persistent viruses, like HIV and herpes viruses, are able to use those nanotubes for intercellular transfer [22–24]. This mechanism of viral spread has not been demonstrated for influenza A viruses. In addition, it was shown recently that tunneling nanotubes promote networking of immune cells and can mediate transfer of MHC class I molecules between distant cells [25]. This function might be disturbed in Lst1 KO mice leading to a slightly enhanced susceptibility to PR8M influenza A. We found in other mouse knock-out lines that the low-virulent PR8 virus (PR8M, [5]) is well suitable to detect even small differences in susceptibility. However, it is still possible that Lst1 KO mice may exhibit a larger difference in phenotype when infected with another influenza virus subtype or variant.

To our knowledge the Lst1 knock-out mouse model described here is the first in vivo model investigating the role of LST1 during influenza A infections. However, several open questions still remain with respect to the many biological functions of LST1 in other contexts. The mouse model which we generated will help to elucidate also these other functions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Peter R.W.A. van Run (Department of Viroscience, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam) for supporting the preparation of the histological slides. This work was supported by intra-mural grants from the Helmholtz-Association (Program Infection and Immunity), a research grant FluResearchNet (No. 01KI07137) and a research grant ‘Infection challenge in the German Mouse Clinic’ from the German Ministry of Education and Research to KS. The work described here was part of a PhD thesis work by SRL at the University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Germany.

Additional file

Targeting and genotyping strategy of the Lst1 KO strain. Mice were genotyped by using different primer pairs leading to PCR products which allowed the identification of wild-type (310 bp), KO (400 bp) and heterozygous animals (310 bp and 400 bp) (A). Primers (blue arrows) used for genotyping: Lst1-fwd: 5′ - GTG CGT GCT CAG TCA CAC TA – 3′; Lst1-rev: 3′ - AGG CCA ACA ATA AGT CCT TAC – 5′; neofwd: 3′ - TCA TTC TCA GTA TTG TTT TGC C – 5′. Abbreviations: lacZ: ß-galactosidase coding sequence from the E.coli lacZ gene, hubiP: promoter from the human ubiquitin C gene, neor: coding sequence for neomycin phosphotransferase, p(A): polyadenylation signal, black arrow: direction of gene transcription, black boxes: Lst1 coding region. To confirm the knock-out of the Lst1 gene in C57BL/6 N-Lst1tm1(KOMP)Vlcg mice we performed reverse transcription. Figure S2. No difference in changes of body weight or survival rate between Lst1 KO and C57BL/6 J mice after infection with H3N2 influenza A virus Male C57BL/6 N-Lst1 tm1(KOMP)Vlcg (n = 7) and C57BL/6 J mice (n = 10) were infected intranasally with 2x10³ FFU H3N2 virus (A/HK/01/68) in 20 μl PBS. Body weight (A) and survival (B) were determined for each day p.i. for a period of 14 days. Percent weight change is shown with reference to the starting body weight. Significances were calculated using non-parametric Mann Whitney U test. (p < 0.01 for day 1) and Logrank test for survival rates (not significant). (PDF 230 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SRL, HK and KS conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript. SRL and BH performed the experiments; BH generated the Lst1 mutant mice from cryopreserved sperm. RLOL determined viral load in lung homogenates. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sarah R. Leist, Email: Sarah.Leist@helmholtz-hzi.de

Heike Kollmus, Email: Heike.Kollmus@helmholtz-hzi.de.

Bastian Hatesuer, Email: Bastian.Hatesuer@helmholtz-hzi.de.

Ruth L. O. Lambertz, Email: Ruth.Lambertz@helmholtz-hzi.de

Klaus Schughart, Email: Klaus.Schughart@helmholtz-hzi.de.

References

- 1.Srivastava B, Blazejewska P, Hessmann M, Bruder D, Geffers R, Mauel S, et al. Host genetic background strongly influences the response to influenza a virus infections. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nedelko T, Kollmus H, Klawonn F, Spijker S, Lu L, Hessman M, et al. Distinct gene loci control the host response to influenza H1N1 virus infection in a time-dependent manner. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:411. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pica N, Iyer A, Ramos I, Bouvier NM, Fernandez-Sesma A, Garcia-Sastre A, et al. The DBA.2 mouse is susceptible to disease following infection with a broad, but limited, range of influenza A and B viruses. J Virol. 2011;85(23):12825–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05930-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boon AC, De Beauchamp J, Hollmann A, Luke J, Kotb M, Rowe S, et al. Host genetic variation affects resistance to infection with a highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus in mice. J Virol. 2009;83:10417–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00514-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blazejewska P, Koscinski L, Viegas N, Anhlan D, Ludwig S, Schughart K. Pathogenicity of different PR8 influenza A virus variants in mice is determined by both viral and host factors. Virology. 2011;412:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuge I, Shen FW, Steinmetz M, Boyse EA. A gene in the H-2S:H-2D interval of the major histocompatibility complex which is transcribed in B cells and macrophages. Immunogenetics. 1987;26:378–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00343709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Baey A, Holzinger I, Scholz S, Keller E, Weiss EH, Albert E. Pvu II polymorphism in the primate homologue of the mouse B144 (LST-1). A novel marker gene within the tumor necrosis factor region. Hum Immunol. 1995;42:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(94)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holzinger I, de Baey A, Messer G, Kick G, Zwierzina H, Weiss EH. Cloning and genomic characterization of LST1: a new gene in the human TNF region. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:315–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00179392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Baey A, Fellerhoff B, Maier S, Martinozzi S, Weidle U, Weiss EH. Complex expression pattern of the TNF region gene LST1 through differential regulation, initiation, and alternative splicing. Genomics. 1997;45:591–600. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulcahy H, O’Rourke KP, Adams C, Molloy MG, O’Gara F. LST1 and NCR3 expression in autoimmune inflammation and in response to IFN-gamma, LPS and microbial infection. Immunogenetics. 2006;57:893–903. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pommerenke C, Wilk E, Srivastava B, Schulze A, Novoselova N, Geffers R, et al. Global transcriptome analysis in influenza-infected mouse lungs reveals the kinetics of innate and adaptive host immune responses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haller O, Arnheiter H, Lindenmann J. Natural, genetically determined resistance toward influenza virus in hemopoietic mouse chimeras. Role of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1979;150:117–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidemann J, Kebschull M, Tepasse PR, Bettenworth D. Regulated expression of leukocyte-specific transcript (LST) 1 in human intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2014;63:513–7. doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mewar D, Marinou I, Lee ME, Timms JM, Kilding R, Teare MD, et al. Haplotype-specific gene expression profiles in a telomeric major histocompatibility complex gene cluster and susceptibility to autoimmune diseases. Genes Immun. 2006;7:625–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagy GR, Gyorffy B, Galamb O, Molnar B, Nagy B, Papp Z. Use of routinely collected amniotic fluid for whole-genome expression analysis of polygenic disorders. Clin Chem. 2006;52:2013–20. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.074971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehner B, Semple JI, Brown SE, Counsell D, Campbell RD, Sanderson CM. Analysis of a high-throughput yeast two-hybrid system and its use to predict the function of intracellular proteins encoded within the human MHC class III region. Genomics. 2004;83:153–67. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(03)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stepanek O, Draber P, Horejsi V. Palmitoylated transmembrane adaptor proteins in leukocyte signaling. Cell Signal. 2014;26:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiller C, Diakopoulos KN, Rohwedder I, Kremmer E, von Toerne C, Ueffing M, et al. LST1 promotes the assembly of a molecular machinery responsible for tunneling nanotube formation. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:767–77. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis DM, Sowinski S. Membrane nanotubes: dynamic long-distance connections between animal cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:431–6. doi: 10.1038/nrm2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiller C, Nowak C, Diakopoulos KN, Weidle UH, Weiss EH. An upstream open reading frame regulates LST1 expression during monocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghunathan A, Sivakamasundari R, Wolenski J, Poddar R, Weissman SM. Functional analysis of B144/LST1: a gene in the tumor necrosis factor cluster that induces formation of long filopodia in eukaryotic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;268:230–44. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eugenin EA, Gaskill PJ, Berman JW. Tunneling nanotubes (TNT) are induced by HIV-infection of macrophages: a potential mechanism for intercellular HIV trafficking. Cell Immunol. 2009;254:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherer NM, Lehmann MJ, Jimenez-Soto LF, Horensavitz C, Pypaert M, Mothes W. Retroviruses can establish filopodial bridges for efficient cell-to-cell transmission. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:310–5. doi: 10.1038/ncb1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sowinski S, Jolly C, Berninghausen O, Purbhoo MA, Chauveau A, Kohler K, et al. Membrane nanotubes physically connect T cells over long distances presenting a novel route for HIV-1 transmission. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:211–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiller C, Huber JE, Diakopoulos KN, Weiss EH. Tunneling nanotubes enable intercellular transfer of MHC class I molecules. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, van Amerongen G, Bestebroer TM, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD. Pathogenesis of influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in a primate model. J Virol. 2001;75:6687–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6687-6691.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]