The provision of commodities is an important element of nearly all public health programs. In HIV programs, commodities can be very expensive, like antiretroviral drugs for treatment or prevention, or they can be relatively cheap, like male condoms. Because of the contrast between incomes in developing countries and the costs of life-saving medications like antiretroviral drugs, recipients are often provided expensive medications free of all charge to increase access and encourage adherence. Condoms, on the other hand, are equally essential for prevention of HIV infection, are relatively inexpensive and are often judged to be affordable for users, even in the most resource-constrained settings. Condoms are often sold at a subsidized price through social marketing programs in an effort to make them even more affordable and, in theory, more valued and likely to be used since they require payment.

Recently, a debate over the relative merit of free versus subsidized distribution of commodities has developed in other areas of public health. [1] The benefits of free versus subsidized distribution of bed nets for malaria prevention, for example, has been debated and examined in a few small-scale studies. [2–4] Given the cost of bed nets relative to disposable income in many countries, the examination of the role of free bed nets is important in the effort to reduce malaria infection. The provision of relatively inexpensive or even heavily subsidized prevention commodities must be considered in the context of the severely constrained resource environments in which they may be provided. As Jim Yong Kim, President of the World Bank, observed in his speech to the 66th World Health Assembly, “Anyone who has provided health care to poor people knows that even tiny out-of-pocket charges can reduce their use of needed services. This is both unjust and unnecessary.” [5]

With the question of whether subsidized pricing or free distribution of essential public health commodities results in greater use and better prevention outcomes being discussed anew, we explored this question for condom distribution as well. We attempted to conduct two parallel systematic reviews, one of condom social marketing and the other of free condom distribution, in low- and middle-income countries. Both reviews followed the PRISMA statement [6] and were an output of the Evidence Project, a joint effort of the Medical University of South Carolina, the World Health Organization and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Mental Health.

The review of condom social marketing yielded valuable information on that approach. [7] Though the number of studies that could be included was limited and the follow-up periods were short, a meta-analysis showed positive and statistically significant effects of social marketing activities on condom use. The analysis suggested that the cumulative effect of condom social marketing over multiple years could be substantial.

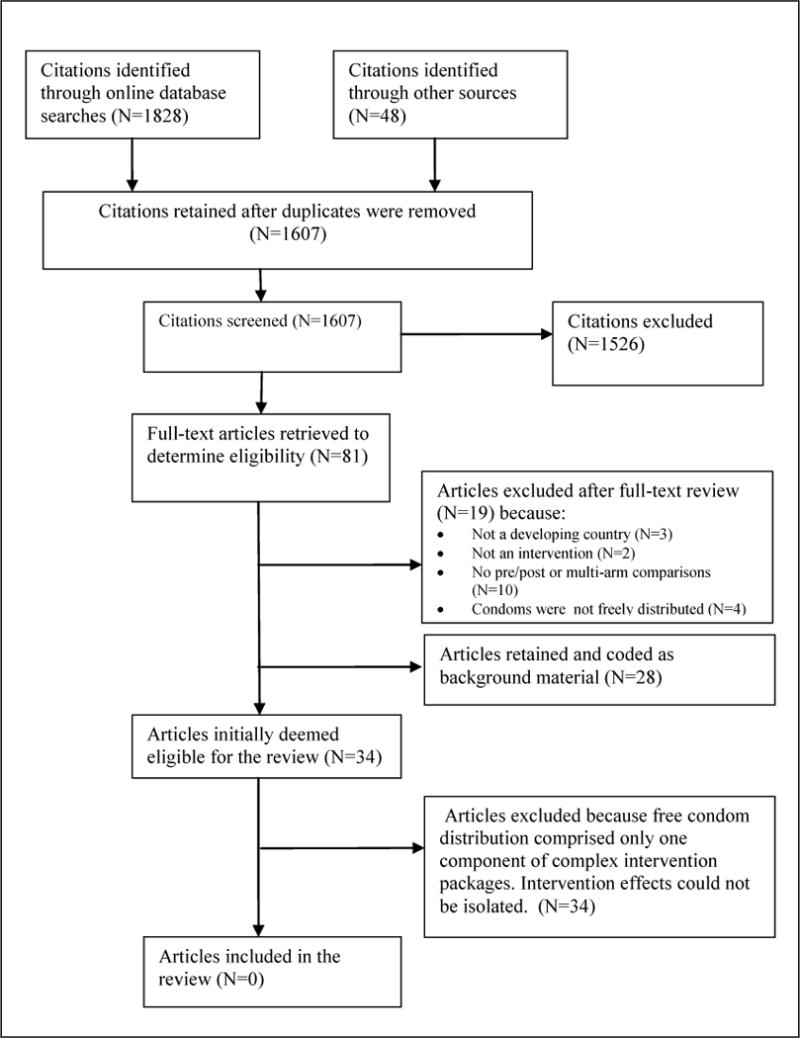

The review of free condom distribution was not successful. Though we identified 34 studies that met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1), all provided free condoms as only one component of a more complete intervention package. As a result, we found that it was not possible to isolate the effect of free condom distribution from other co-occurring interventions in the available research literature. We also concluded that it is equally likely many other studies evaluating key interventions distributed condoms for free without noting that fact in the publication. Our main conclusion from this review is that insufficient attention has been paid to evaluating the effect of free condom distribution on condom use and other key HIV prevention outcomes.

Figure 1.

Free Condom Distribution: Flow chart depicting disposition of study citations

Condoms are relatively inexpensive per item. Perhaps as a result, the impact of their cost as a potential barrier to their use has not been examined. The total annual expenditure for condoms worldwide is very large. With levelling or decreasing resources for HIV prevention, maximizing the effectiveness of prevention investments is becoming even more crucial. At the same time, the desire to decrease prevention expenditures by increasing users’ contributions to commodity costs is growing, supported by the belief that users value more what they purchase over what they receive for free.

Research from behavioural economics demonstrates the attractiveness of “free” in marketing commodities [8] and evidence from malaria prevention has shown the effect of free commodities on increased use. Studies have been done on price sensitivity of socially marketed condoms and have shown a clear negative correlation between condom prices and sales. [9] However, given the vast number of free condoms distributed each year, it is surprising how little is known about the actual effect on condom use. We recommend well-designed studies to isolate the effect of free versus subsidized or socially marketed condom distribution on condom use.

References

- 1.Hoffman V, Barret C, Just D. Do free goods stick to poor households? Experimental evidence on insecticide-treated bednets. World Development. 2009;37(3):607–617. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macedo de Oliveira A, Wolkon A, Krishnamurthy R, Erskine M, Crenshaw DP, Roberts J, Saúte F. Ownership and usage of insecticide-treated bed nets after free distribution via a voucher system in two provinces of Mozambique. Malar J. 2010 Aug 4;9:222. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hightower A, Kiptui R, Manya A, Wolkon A, Vanden Eng JL, Hamel M, Noor A, Sharif SK, Buluma R, Vulule J, Laserson K, Slutsker L, Akhwale W. Bed net ownership in Kenya: the impact of 3.4 million free bed nets. Malar J. 2010 Jun 24;9:183. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beer N, Ali AS, de Savigny D, Al-Mafazy AW, Ramsan M, Abass AK, Omari RS, Björkman A, Källander K. System effectiveness of a targeted free mass distribution of long lasting insecticidal nets in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Malar J. 2010 Jun 18;9:173. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JY. Poverty, health and the human future; Presented at the 66th World Health Assembly; Geneva, Switzerland. 21 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweat MD, Denison J, Kennedy C, Tedrow V, O’Reilly K. Effects of condom social marketing on condom use in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis: 1990–2010. Bull World Health Org. 2012;90:613–622. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.094268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ariely D. Predictably Irrational: the hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey PD. The impact of condom prices on sales in social marketing programs. Stud Fam Plann. 1994 Jan-Feb;25(1):52–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]