Abstract

Background

Cannabis use disorder is associated with substantial morbidity and, after alcohol, is the most common drug bringing adolescents and adults into treatment. At present, there are no FDA-approved medications for cannabis use disorder. Combined pharmacologic interventions might be particularly useful in mitigating withdrawal symptoms and promoting abstinence.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of dronabinol, a synthetic form of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, a naturally occurring pharmacologically active component of marijuana, and lofexidine, an alpha-2 agonist, in treating cannabis dependence.

Methods

One hundred fifty six cannabis-dependent adults were enrolled and following a 1-week placebo lead-in phase 122 were randomized in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 11-week trial. Participants were randomized to receive dronabinol 20 mg three times a day and lofexidine 0.6 mg three times a day or placebo. Medications were maintained until the end of week eight, were then tapered over two weeks and patients were monitored off medications during the last study week. All participants received weekly motivational enhancement and relapse prevention therapy. Marijuana use was assessed using the timeline follow-back method.

Results

There was no significant difference between treatment groups in the proportion of participants who achieved 3 weeks of abstinence during the maintenance phase of the trial (27.9 % for the medication group and 29.5% for the placebo group), although both groups showed a reduction over time.

Conclusions

Based on this treatment study, the combined intervention did not show promise as a treatment for cannabis use disorder.

Keywords: Marinol, Dronabinol, Lofexidine, Cannabis Use Disorder, Marijuana Dependence, Cannabis withdrawal

1. INTRODUCTION

Marijuana use has progressively increased over the past decade, with approximately 19.8 million Americans over the age of 12 estimated to have used marijuana in the past month (SAMHSA, 2014). With the exception of alcohol, marijuana is the primary substance bringing Americans into their most recent substance abuse treatment episode (SAMHSA, 2014). Although there has been substantial work assessing various psychotherapeutic strategies for cannabis use disorders (Budney et al., 2011, 2006; Dennis et al., 2004; McRae et al., 2003) most patients with cannabis use disorder continue to use. Up until this time most of the medication development studies have consisted of laboratory studies (Cooper and Haney, 2010), although the outpatient treatment literature is growing. A recent review looked at 14 pharmacologic treatment studies targeting cannabis use disorder and concluded that there was inadequate evidence to support the utility of any specific medication, perhaps not surprising given the heterogeneity of medications studied, study quality, and variability in study outcomes (Marshall et al., 2014). One of its conclusions was that some agents, such as gabapentin and the glutamatergic modulator, N-acetylcysteine, or combination therapies warrant further investigation.

Dronabinol (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, THC) is a cannabinoid receptor partial agonist, and has been a reasonable choice to test as a treatment for cannabis use disorders since other partial agonists have been found to be effective for other substance use disorders (i.e., buprenorphine for opiate use disorders and varenicline for nicotine use disorder). While dronabinol has shown benefit in reducing some withdrawal symptoms and subjective effects of marijuana (Haney et al., 2004; Hart et al., 2002), it has not been shown to alter smoked marijuana self-administration under laboratory conditions (Haney et al., 2008; Hart et al., 2002). Similarly, dronabinol has been shown to reduce withdrawal symptoms and improve retention in an outpatient treatment trial, but was not superior to placebo in reducing marijuana use or promoting abstinence (Levin et al., 2011).

Because emerging evidence suggests that dronabinol may not treat all aspects of cannabis use disorder, it was hypothesized that augmentation with an agent exhibiting complementary pharmacologic properties would provide added benefit. Lofexidine, an α2 noradrenergic agonist, has been hypothesized to be helpful at dampening cannabis withdrawal and craving given its utility in treating opioid withdrawal and in reducing stress-induced and cue-induced opioid craving (Sinha et al., 2007). Indeed, Haney et al. (2008) found that the combination of lofexidine and dronabinol (Lofex-Dro) was superior to placebo in improving sleep and other cannabis withdrawal symptoms; the combination also outperformed either lofexidine or dronabinol alone in mitigating withdrawal symptoms. Thus, we carried out a double-blind placebo-controlled 11-week trial testing lofexidine and dronabinol for the treatment of cannabis use disorder. We hypothesized that lofexidine and dronabinol (Lofex-Dro) would be superior to placebo in reducing withdrawal and achieving abstinence.

2. METHODS

2.1 Study Participants

As described in our prior marijuana treatment studies (Levin et al., 2011, 2013; Mariani et al., 2010), all participants were seeking outpatient treatment for problems related to marijuana use and were recruited by local advertising. The medical screening included a history and physical examination, an electrocardiogram, and laboratory testing (Levin et al., 2011). The psychiatric evaluation included the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders- Axis I disorders DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; First, 1995). A Timeline Follow Back (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell, 1992) assessment was conducted for marijuana, nicotine, alcohol and other drugs for the past 30 days. Participants were treated at the Substance Treatment and Research Service (STARS) of Columbia University/ New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI). Study enrollment occurred from December, 2009 through May, 2014 with study completion in September, 2014.

Eligible participants were: 1) between the ages of 18-60, 2) meeting DSM-IV criteria for current marijuana dependence, 3) using marijuana ≥ 5 days/week and 4) providing a THC-positive urine on the day of study entry (as measured by a qualitative on-site dip test). Participants were excluded for the following: 1) severe mental illness (e.g., bipolar illness; schizophrenia); 2) unstable physical condition; 3) history of a seizure disorder; 4) current suicidal risk; 5) observed cognitive difficulties; 6) bradycardia (< 50 beats/minute), hypotension (sitting or standing BP < 90/50); 7) currently nursing, pregnant, or, if a women refusing to use an effective method of birth control; 8) physiologically dependent on any other drugs (excluding nicotine) that would require a medical intervention; 9) known sensitivity to dronabinol or lofexidine; 10) coronary vascular disease; 11) currently being treated with an alpha-2 agonist antihypertensive medication; 12) currently being prescribed a psychotropic medication (however, medication for depression, anxiety, and ADHD was allowed if stable for at least 1 month); 13) a job in which even mild marijuana intoxication would be hazardous; and 14) court-mandated to treatment. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NYSPI and all participants provided written informed consent. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov: Identifier NCT01020019

2.2 Study Design

The study was a randomized, double-blind, 11-week clinical trial comparing placebo to the combination of lofexidine and dronabinol (Lofex-Dro). The whole study included a one-week placebo lead-in phase, followed by randomization and a 2-week medication titration phase, a 6-week medication maintenance phase, a 2-week dose taper phase, followed by a one-week placebo lead-out phase. Participants were randomized at the end of the placebo lead-in phase using computer generated random blocks of sizes 4, 6, and 8, with a 1:1 allocation ratio stratified by joints used per week [<21 (n=49) versus ≥21 (n=73)]. A Ph.D. statistician at Columbia University independent of the research team conducted the randomization and maintained the allocation sequence. Participants, investigators and study staff were blind to allocation. A study timeline figure and a table detailing the scheduling of assessments and procedures have been included in the Supplemental Section (Figure 1 and Table 1 respectively)1.

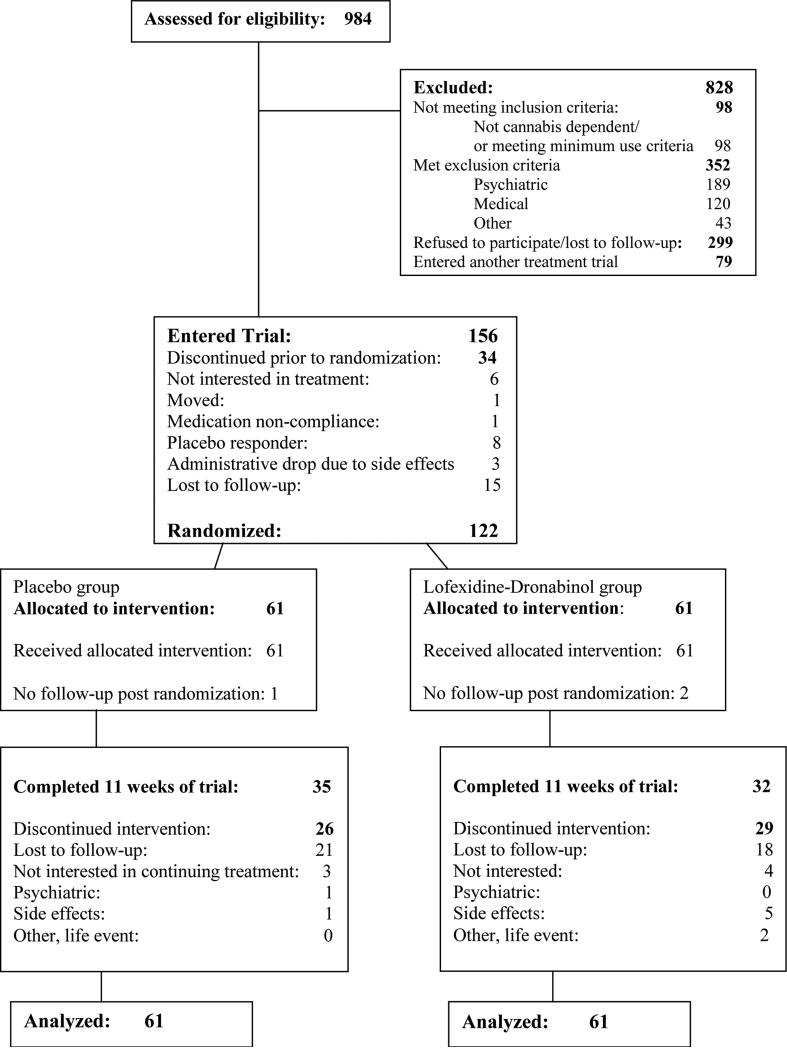

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants recruited to trial.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the patients randomized to placebo and lofexidine+dronabinol (N=122)

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=61) | Lofex-Dro (n=61) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Age (years) | 35.4 (10.8) | 34.8 (11.2) |

| Male | 45 (73.8%) | 39 (63.9%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 15 (24.6%) | 17 (27.9%) |

| Black | 17 (27.9%) | 18 (29.5%) |

| White | 26 (42.6%) | 21 (34.4%) |

| Other | 3 (4.9%) | 5 (8.2%) |

| Education | ||

| High school | 18 (29.5%) | 19 (31.1%) |

| Some college | 17 (27.9%) | 15 (24.6%) |

| College | 17 (27.9%) | 18 (29.5%) |

| Graduate school | 9 (14.8%) | 9 (14.8%) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 24 (39.3%) | 17 (27.9%) |

| Part-time | 6 (9.8%) | 10 (16.4%) |

| Student | 7 (11.5%) | 8 (13.1%) |

| Unemployed/others | 24 (39.3%) | 26 (42.6%) |

| Currently married | 14 (23.0%) | 10 (16.4%) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist | ||

| Withdrawal Discomfort Score (WDS)-10 | 7.3 (4.0) | 7.0 (4.7) |

| Marijuana Craving Questionnaire (MCQ) | ||

| MCQ: Compulsion | 8.3 (4.4) | 8.7 (4.0) |

| MCQ: Emotion | 8.8 (4.9) | 10.1 (4.9) |

| MCQ: Expectancy | 11.6 (4.1) | 11.8 (5.0) |

| MCQ: Purposefulness | 11.4 (5.1) | 11.8 (5.6) |

| MCQ: Total score | 40.1 (15.4) | 42.4 (16.9) |

| Hamilton-Depression (21-item) | 5.3 (3.5) | 5.3 (4.1) |

| Patterns of drug use | ||

| Age at first use | 16.1 (3.0) | 15.8 (2.9) |

| Age at regular use | 18.6 (3.4) | 19.3 (6.1) |

| median (IQR) | ||

| Days of use in last 7 days | 7 (7-7) | 7 (7-7) |

| Days of use in last 28 days | 28 (27-28) | 28 (27-28) |

| Amount spent per using day ($) | 20.0 (10-40) | 17.6 (11.5-24.8) |

| Amount per using day (g) | 1.6 (0.9-3.8) | 1.7 (0.8-2.4) |

* Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

2.2.1 Medication

Lofex-Dro or matching placebo (PBO) was prepared by the un-blinded pharmacy at the NYSPI, packaged in matching gelatin capsules with lactose filler and an equal amount of riboflavin (25 mg in each capsule) and was taken three times a day. The riboflavin marker procedure is a standard method to measure adherence to study medication in a clincal trial (Del Boca et al., 1996).

To minimize risks associated with study medication, we instructed patients to take the first dose of their assigned medication (week 1, day 1) 3-4 hours prior to their study appointment. This allowed medical staff to evaluate side effects and vital sign changes. Because lofexidine can lower blood pressure, at each weekly visit, blood pressure was closely monitored. If there was a significant drop in blood pressure, medication dose was adjusted and if necessary, discontinued.

Lofex-Dro or matching PBO was given in a “fixed-flexible” dose schedule with the dose titrated to 1.8 (0.6 three times a day) and 60 mg (20 mg three times a day) per day or the maximum tolerated dose. Lofexidine was titrated in 0.2 mg increments and dronabinol was given in 10 mg increments until maximum or tolerated dose was reached. If the participant could not tolerate at least 10 mg/day of dronabinol and 0.2 mg/day lofexidine, the medication was discontinued.

Study medication was provided to participants on a weekly basis. Each week, participants were asked to return all bottles and unused medication. The placebo lead-in phase allowed us to randomize only those participants who demonstrated compliance with study procedures and to assess if some participants were able to abstain during the first week of the study without receiving active medication. Participants who reported marijuana use less than once a week during the placebo lead-in phase were considered placebo responders (n=8) and were not randomized but were followed clinically and offered motivational/relapse prevention therapy.

2.2.2 Manualized Psychotherapy

All participants received manualized motivational enhancement and cognitive behavioral/relapse prevention therapy (Steinberg et al., 2005). Patients were encouraged to set a quit date two weeks after starting study medication. However, if they could not commit to this, a temporary goal of use reduction was set and eventually a new quit date. Because motivational enhancement therapy is designed to “meet patients where they are,” we worked with them to set their own goals and if appropriate, establish a time when they might be interested in sampling abstinence.

Therapy sessions were provided by doctoral or master's level therapists who are experienced in providing motivational enhancement and cognitive behavioral/relapse prevention therapy.

2.2.3 Participant Fees

Participants were reimbursed for travel to and from the clinic. The amount of reimbursement varied between $5.00-$20.00 in cash per visit which was dependent on commuting distance.

2.3 Treatment Assessments

2.3.1 Marijuana Use

Participants provided a urine specimen, had their vital signs taken, were assessed for side effects and completed self-report instruments at each study visit. A timeline follow-back (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) assessment modified for marijuana was conducted at each of the two weekly visits. The initial phase of the TLFB interview asked participants their preferred method of use (e.g., joints, blunts, pipe, or ingestion) and to estimate the amount of marijuana used in the preferred method. The estimated amount was facilitated by using a surrogate substance (oregano) that provided a basis to quantify the dollar value of the amount of marijuana measured (Levin et al., 2011). Details of this procedure are provided in earlier studies developed by our group and allow a better quantification of amount of use (Levin et al., 2011; Mariani et al., 2010). At each subsequent twice-weekly clinic visit cannabis, alcohol and drug use was assessed using the TLFB and the use on days between clinic visits was measured.

While self-reported use has its limitations, it is commonly used in alcohol pharmacologic treatment trials (Johnson et al., 2007; Wilens et al., 2008) and numerous clinical trials in drug abusing samples have found it to be a valid approach in determining ongoing drug use (Carpenter et al., 2009; Carroll et al., 1994; Nunes et al., 1998). A strong association had previously been found between self-report and urine drug screens, validating the self-report as a reliable method to measure marijuana use (Levin et al., 2011).

2.3.2 Marijuana Craving and Withdrawal

Marijuana Craving was assessed weekly using the modified 12-item Marijuana Craving Questionnaire (MCQ; Heishman et al., 2001). Each of the items is rated on a seven point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Marijuana withdrawal was assessed using the withdrawal checklist (Budney et al., 1999), a 10-item self-report instrument in which symptoms are rated either none, mild, moderate or severe (ranging respectively from 0-3) for a possible total score of 30.

2.3.3 Adverse Effects

The Modified Systematic Assessment for Treatment and Emergent Events (SAFTEE) (Johnson et al., 2005; Levine and Schooler, 1986) was conducted weekly by the study psychiatrist to assess for adverse effects. The persistence or resolution of all adverse effects was logged weekly.

2.4 Data Analysis

The primary aim was to compare the odds of achieving “consecutive abstinence” (defined as at least 21 consecutive days of abstinence based on TLFB self-report post randomization during titration and maintenance phase) between the active treatment group (Lofex-Dro) versus the placebo group (PBO). Secondary outcomes were a dichotomous abstinence during the last two weeks of the maintenance medication phase of the trial, a continuous peak withdrawal (maximum score over the maintenance medication phase), a continuous longitudinal weekly withdrawal, a continuous longitudinal weekly proportion of days of use, a dichotomous longitudinal weekly marijuana use, and time to dropout of treatment. Longitudinal outcomes were analyzed during titration and maintenance phase.

The dichotomous primary outcome “consecutive abstinence” was analyzed using a logistic regression model as a function of treatment (Lofex-Dro vs. PBO) and baseline amount of marijuana use (a natural log transformed total grams of marijuana 1 month prior to treatment). The dichotomous measure abstinence (yes or no) during the last two weeks was analyzed similarly to the primary outcome. Peak withdrawal was analyzed using a linear model as a function of treatment, baseline amount of marijuana use, and baseline withdrawal score. Each longitudinal outcome was analyzed using a generalized mixed effects model using identity (for continuous) or logit (for dichotomous) link function with a random subject effect and autoregressive (AR1) covariance structure to account for within subject correlation over time. Each outcome was modeled as a function of treatment, time, treatment-by-time interaction, baseline amount of marijuana use, and baseline measure of the outcome when appropriate. If the treatment-by-time interaction was not found to be significant, the interaction term was omitted and a model with only main effects was fit. The interaction between treatment and baseline amount of marijuana use was also tested in the models described above to assess possible moderator effects, but no significant interactions were found and thus results for these models will not be presented in the results section.

Medication dosing and medication adherence were tested between treatment groups using non-parametric t-tests (Mann-Whitney U tests), due to the non-normally distributed nature of these data. To compare the proportion of subjects who tolerated the maximum dose of each medication, chi-square tests were used. Side effects and adverse events occurrences were tested using Fisher's Exact tests.

All analyses were conducted on the intent-to-treat sample. All statistical tests were 2-tailed level of significance level of 5%. Power analyses were conducted using PASS for logistic regression, with assumptions based on current literature and our previous dronabinol trials. It was determined that a sample of 150 subjects would have 80% power to detect a significant difference in abstinence rates of 22% in PBO and 45% in Lofex-Dro. However, a total of 122 subjects were randomized and the abstinence rates observed were 29.51% in PBO and 27.87% in Lofex-Dro. This negative and very small difference would not be found significant even with large sample (e.g., 1000 patients) and the results found in this paper are not likely due to the under sampling.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Participants

The CONSORT diagram shows participant flow through the study (Figure 1). Screening of 984 individuals yielded 156 participants meeting eligibility criteria who were enrolled in the trial with 122 participants being randomized following the placebo lead-in week. Common reasons for non-randomization included placebo responders and those who were no longer interested in treatment (see Figure 1). Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of randomized participants are shown in Table 1. The sample was predominantly male, in their mid-thirties, unmarried, and unemployed, with 39% White, 27% Hispanic, and 29% African-American. The majority of the sample reported smoking marijuana every day during the prior 28 days to study entry (Table 1). Forty-three participants (35%) dropped out prior to maintenance phase completion (end of week 8 post randomization).

3.2 Primary Outcome: Dichotomous any 21-days consecutive abstinence

The observed proportion of subjects achieving abstinence during any 21 days was 17/61 (27.87%) in Lofex-Dro and 18/61 (29.51%) in PBO. There was not a significant effect of treatment on achieving consecutive abstinence (X12=0.17, p = .68). However, there was a significant effect of baseline amount of marijuana on achieving 21-days consecutive abstinence; the odds of achieving consecutive abstinence significantly decreased as baseline amount of marijuana use increased (X12=10.12, p = .002).

3.3 Secondary outcomes

3.3.1 Marijuana abstinence during last 2 weeks of maintenance medication phase

The observed proportion of subjects achieving abstinence in the last 2 weeks of maintenance medication phase of the trial was 12/61 (19.67%) in Lofex-Dro and 12/61 (19.67%) in PBO. There was not a significant effect of treatment on achieving two consecutive weeks of abstinence (X12 = 0.02, p = .89, see Table 2). However, there was a significant effect of baseline amount of marijuana on achieving abstinence during the last 2 weeks of maintenance medication phase, the odds of achieving abstinence significantly decreased as baseline amount of marijuana use increased (X12 = 5.79, p = .02).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Cannabis Use Outcomes Analyses

| Outcome | Predictors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Treatment | Time | Time by Treatment Interaction | ||

| Baseline Marijuana Use | Baseline Withdrawal | ||||

| Primary Outcome: Any 21-days consecutive abstinence | X12 = 10.12, p-value = .002 | N/Ae | X12 = 0.17, p-value = .68 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| Secondary Outcome: Abstinence during last 2 weeks | X12 = 5.79, p-value = .02 | N/Ae | X12 = 0.02, p-value = .89 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| Secondary Longitudinal Outcome: Weekly proportion of days of marijuana use | F1, 637 = 11.20, p-value = .0009 | N/Ae | F1, 637 = 0.40, p-value = .53 | F7, 637 = 15.11, p-value <.0001 | NSb |

| Secondary Longitudinal Outcome: Weekly dichotomous marijuana use | F1, 637 = 11.64, p-value = .0007 | N/Ae | F1, 637 = 0.14, p-value = .71 | F7, 637 = 16.36, p-value <.0001 | NSc |

| Secondary Outcome: Peak withdrawal score | t115 = 0.37, p-value = .71 | t115 = 5.75, p-value <.0001 | t115 = 0.61, p-value = .54 | N/Aa | N/Aa |

| Secondary Longitudinal Outcome: Weekly withdrawal score | F1, 633 = 0.84, p-value = .36 | F1, 633 = 44.07, p-value <.0001 | F1, 633 = 0.05, p-value = .83 | F7, 633 = 2.30, p-value = .03 | NSd |

| Retention | N/Af | N/Af | X12=1.36, p-value = .24 | N/Af | N/Af |

Only longitudinal model included terms: Time and Time by Treatment interactions..

Time by Treatment interaction was not significant (F7, 630 = 0.53, p = .81) and was omitted from the final model.

Time by Treatment interaction was not significant (F7, 630 = 1.88, p = .07) and was omitted from the final model.

Time by Treatment interaction was not significant (F7, 626 = 0.71, p = .67) and was omitted from the final model.

Only withdrawal outcome models include Baseline Withdrawal term.

Retention was analyzed with Kaplan Meier Curves and Log-Rank statistics as a function of treatment and without any other covariates.

3.3.2 Weekly withdrawal score

In the main effects model, there was not a significant effect of treatment on withdrawal scores across time (F1, 633 = 0.05, p = .83 see Table 2). There was not a significant effect of baseline amount of marijuana use was on withdrawal scores across time (F1, 633 = 0.84, p = .36). However, withdrawal scores did significantly decrease over time (F7, 633 = 2.30, p = .03). An increase in baseline withdrawal score was also significantly associated with an increase in withdrawal score across time (F1, 633 = 44.07, p <.0001).

3.3.3 Retention in Treatment (Time to dropout)

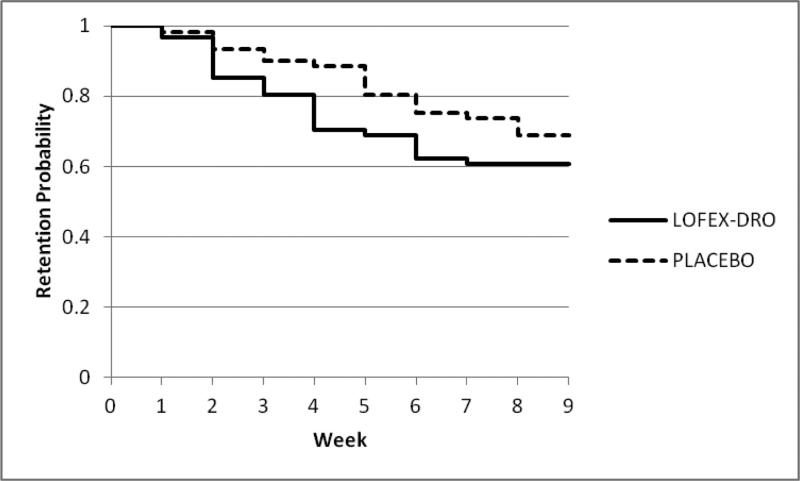

The observed proportion of subjects completing the titration and maintenance medication phases of the trial were 37/61 (60.66%) in Lofex-Dro and 42/61 (68.85%) in PBO. The survival curves are shown in Figure 2. There was not a significant difference in retention between treatment groups (X12=1.36, p = .24, see Table 2).

Figure 2.

The survival curves describing retention in treatment for the Lofex-Dro and PBO groups.

3.4 Treatment Adherence

3.4.1 Medication

Medication dosing statistics were calculated using the 95 individuals that reached the maintenance phase, with 52 subjects in the placebo group and 43 subjects in the Lofex-Dro group. The mean tolerated doses of the medication for the Lofex-Dro groups was 55.6 ± 13.1 mg/day for dronabinol and 1.28 ± .64 mg/day for lofexidine compared to mean tolerated doses of assigned medication in the placebo group of 60.0 ± 0.0 mg/day for placebo dronabinol (Mann-Whitney U test: U = 1934, p = .01) and 1.74 ± 0.26 mg/day for placebo lofexidine (U = 1641.5, p <.0001).

The median rates of medication adherence as determined by self-reported pills taken in the Lofex-Dro group were 95.5% (Interquartile range: 86.4% - 98.2%) for dronabinol pills and 94.8% (IQR: 85.5% – 98.1%) for lofexidine pills. In the placebo group, the median rates of medication adherence were 95.0% (IQR: 85.7% - 100%) for dronabinol pills and 94.6% (IQR: 84.5% - 97.9%) for lofexidine pills. These rates did not significantly differ between treatment groups (dronabinol: U = 3757.5, p = .50, lofexidine: U = 3549, p = .67). The median percentage of samples that fluoresced for riboflavin was 100% (IQR: 95.2% - 100%) for Lofex-Dro group and 100% (IQR: 94.9% - 100%) for placebo (U = 3693, p = .83).

3.4.2 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

On average, participants completed a mean of 7.5 (SD = 3.6) of 12 CBT sessions with no significant differences across groups: Lofex-Dro: 7.3 (SD = 3.9) and PBO: 7.7 (SD = 3.2) (T120 = 0.62, p = .54).

3.5 Side effects and adverse events

All adverse events are presented in Table 3. Dry mouth, intoxication, and hypotension were more common in the active treatment arm compared to the placebo group (respectively, p < .001, p = .004, p = .008). However, anxiety was less common in the Lofex-Dro arm (p = .044). There were two Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) during the trial, one in each arm of the study and both taking place during the placebo-lead out week. One individual in the active medication group of the study was seen in an ER for severe abdominal pain during the lead-out phase. One individual in the placebo group entered a detoxification program during the placebo lead-out week. Neither SAE were considered to be directly related to study procedures.

Table 3.

Adverse events reported by treatment group during the trial

| Placebo (N=61) | Lofex-Dro (N=61) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | N (%) | N (%) | p-value |

| Any Adverse Event | 46 (75.4) | 47 (77.0) | 1.000 |

| Dry Mouth | 6 (9.8) | 27 (44.3) | <.001 |

| Fatigue | 15 (24.6) | 26 (42.6) | .055 |

| Light headed/Dizziness | 12 (19.7) | 21 (34.4) | .102 |

| Insomnia | 13 (21.3) | 13 (21.3) | 1.000 |

| Intoxication | 2 (3.3) | 13 (21.3) | .004 |

| Headache | 12 (19.7) | 10 (16.4) | .814 |

| Anxiety | 11 (18.0) | 3 (4.9) | .044 |

| Hypotension | 1 (1.6) | 10 (16.4) | .008 |

| Drowsiness | 4 (6.6) | 9 (14.8) | .240 |

| URI | 8 (13.1) | 2 (3.3) | .095 |

| Nausea | 5 (8.2) | 6 (9.8) | 1.000 |

| Irritability | 6 (9.8) | 3 (4.9) | .491 |

| Decreased Appetite | 6 (9.8) | 2 (3.3) | .272 |

| Sweating | 5 (8.2) | 5 (8.2) | 1.000 |

| Depression | 5 (8.2) | 3 (4.9) | .717 |

| GI Upset | 5 (8.2) | 2 (3.3) | .439 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (6.6) | 2 (3.3) | .680 |

| Vomiting | 4 (6.6) | 2 (3.3) | .680 |

| Fever | 4 (6.6) | 1 (1.6) | .365 |

| Orthostasis | 1 (1.6) | 4 (6.6) | .365 |

| Sore Throat | 3 (4.9) | 2 (3.3) | 1.000 |

| Gas | 1 (1.6) | 3 (4.9) | .619 |

| Confusion | 1 (1.6) | 3 (4.9) | .619 |

| Rash | 3 (4.9) | 0 (0) | .244 |

4. DISCUSSION

In contrast to our hypothesis, the concurrent administration of lofexidine and dronabinol was not found to be more effective than placebo for promoting abstinence, reducing withdrawal symptoms, or retaining individuals in treatment. This was surprising given that a prior trial found that dronabinol 40 mg a day, outperformed placebo in reducing withdrawal symptoms and improving retention, albeit not abstinence (Levin et al., 2011).

In the prior trial, when we failed to find a higher abstinence rate in the dronabinol arm, we hypothesized that it might have been due to inadequate dosing. Additionally, we assumed that the addition of lofexidine would enhance the potential therapeutic benefit of dronabinol by mitigating withdrawal symptoms and reducing stress-induced relapse via an alternative physiologic mechanism.

An unexpected finding from this study was the difficulty participants had in tolerating the maximum doses. Whereas the Haney et al (2008) study found that lofexidine was well-tolerated at 0.6 mg four times a day in the laboratory, 40% of our patients in the active treatment arm could not tolerate 0.6 mg three times a day. The close observation in the laboratory setting allowed the investigators to administer the next dose of the day even if an earlier dose was held. Alternatively, in the outpatient treatment setting, blood pressure holding parameters and complaints of dizziness or fatigue required doses to be held or lowered until the next visit. Often participants would not want their dose raised or the study physicians were concerned that raising the dose would lead to functional difficulties or untoward adverse events; these factors led to lower lofexidine dosing in the outpatient setting.

Another reason we did not observe an effect might have been due to the design of the study. In the laboratory study, the combined intervention reduced self-administration after a period of abstinence. The laboratory model is a relapse prevention model. Whereas, the clinical trial was designed to test abstinence initiation followed by relapse prevention. It may be that this medication combination is ineffective at inducing abstinence, and since few patients achieved abstinence, a relapse prevention effect could not be demonstrated. A design in which abstinence is induced by hospitalization as a first step might be better able to demonstrate the effect of a medication/medication combination that mainly prevents relapse. Allsop et al (2014) found that nabixomols (a combination medication of THC and cannabidiol) was superior to placebo in reducing withdrawal symptoms in the inpatient setting but there was no advantage of nabixomols in marijuana use reduction once participants were assessed at the 28-day outpatient follow-up. Since nabixomols was discontinued prior to discharge from the inpatient setting, it is unclear whether maintenance on nabiximols would reduce the likelihood of relapse.

Notably, a recent trial in adolescents with cannabis use disorder combined n-acetylcysteine with contingency management for negative THC urines (Gray et al., 2012). The investigators found that n-acetylcysteine was more likely to produce negative urines than the placebo group. While we do not know whether n-acetylcysteine would be efficacious without contingency management, it does suggest that a procedure that enhances abstinence might be preferable. If the medication(s) are thought to work by reducing withdrawal symptoms or hinder relapse among those who initially quit, then the powerful reinforcement provided by the contingency management procedure might provide the necessary behavioral platform to detect a medication effect.

A problem with dronabinol from a methodological standpoint is that it produces positive THC urines, even in the absence of marijuana ingestion, rendering it not possible to confirm self-reported abstinence and to provide rewards for negative THC urines in a contingency management framework. A possible solution might be to test nabilone, rather than dronabinol, as a treatment for cannabis use disorder. Notably, nabilone has better bioavailability (Ben Amar, 2006; Lemberger et al., 1982), is potent, and has shown little evidence of abuse (Haney et al., 2013; Lemberger et al., 1982). Further, ingestion of nabilone yields urinary metabolites that are unique from those produced from marijuana use; thus it can be differentiated from marijuana ingestion (Bedi et al., 2013; Fraser and Meatherall, 1989). Unlike dronabinol, nabilone has been shown to decrease marijuana relapse in a laboratory paradigm with heavy marijuana non-treatment seekers (Haney et al., 2013).

While the rate of abstinence in this trial was low (30% achieved abstinence at any time point, 20% abstinent at end of study), approximately half of patients reported a reduction in cannabis use of 50% or more. This suggests that the behavioral therapy offered to all patients in the trial had some effectiveness, although not surprisingly abstinence is harder to achieve than reduction in use. Further research is needed to examine whether a reduction in cannabis use, short of abstinence, is a clinically significant outcome producing improved long term prognosis. In any case, in the present study there was no impact of the medication combination on either abstinence or reduction in use.

There are some important strengths of this study (e.g., relatively large sample size for a single-site study and reasonable medication adherence). However, there are several limitations. First, the outcome measure was based solely on self-report rather than urine toxicological results. While there may have been some under-reporting of use, this is likely to have been the case for both treatment arms and not likely to have affected our results. Further, there are data demonstrating that when there are no negative contingencies for reporting use, self-reports are consistent with urine results (Decker et al., 2014). Second, approximately 35% did not complete the maintenance phase of the trial. A methodological problem here is that the abstinence status of dropouts at this study point is not known, although it would seem a reasonable assumption that most dropouts continue to use cannabis. Additionally, earlier studies, including our own research group, have had higher drop-out rates in adults enrolled in pharmacotherapy trials targeting cannabis use disorders, than this current trial. Thus there has been progress in retaining our participants in treatment.

Finally, this trial was not designed to test dronabinol alone or lofexidine alone as treatments for cannabis use disorder. Based on the laboratory study (Haney et al., 2008), and our prior negative trial using a lower dose of dronabinol, we decided to test the combined intervention. From a practical standpoint, given that the combination did not show an effect, finding an effect of either medication alone seems unlikely utilizing the same methodology. It might be that the combination of dronabinol 60 mg/day and lofexidine 1.8 mg/day provided in divided dosing in the laboratory (and well-tolerated), was not as well-tolerated when given in the outpatient setting because participants continued to use marijuana. Moving forward, as suggested above, it might be best to initiate abstinence, and perhaps test lofexidine at lower doses.

In sum, we did not find the combination of dronabinol and lofexidine effective in promoting abstinence among cannabis dependent patients. Thus, this clinical trial fails to replicate the promising findings from a human laboratory study that showed dronabinol plus lofexidine reduced cannabis self-administration (Haney et al., 2008). The laboratory model tested the medication combination after abstinence had been induced through hospitalization. Thus, it is possible that the medication exerts primarily a relapse-prevention effect, and future clinical trials might consider beginning with a hospitalization for detoxification prior to randomization. Future studies might also consider testing another cannabis analogue, nabilone, which has greater bioavailability and potency than dronabinol.

Supplementary Material

Highlights (for review).

One of the few large double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trials for cannabis dependence.

Participants were randomized to receive dronabinol plus lofexidine or placebo.

There was no significant difference between treatment groups in the proportion of participants who achieved 3 weeks of abstinence during the maintenance phase of the trial, although both groups showed a reduction in use over time.

There was not a significant effect of treatment on withdrawal scores across time, although withdrawal scores did significantly decrease over time.

Based on this treatment study, the combined intervention did not show promise as a treatment for cannabis use disorder.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the staff of the Substance Treatment and Research Service (STARS) of the New York State Psychiatric Institute for their clinical support.

Role of funding source

Funding for this research was provided by NIDA grants P50DA09236 and KO2 000465. NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. US WorldMed supplied lofexidine and matched placebo for this trial but had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Trial Registration: NCT01020019

Contributors

Author Levin designed the study, wrote the protocol and served as PI of the study. Authors Glass, Pavlicova and Brooks undertook the statistical analysis, and authors Levin, Brooks and Glass wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Author Mahony was responsible for many aspects of study implementation, data collection and organization, IRB coordination and other study features. Authors Mariani, Bisaga and Sullivan served as study physicians. All authors contributed to, edited and have approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Conflict of interest

Dr. Levin received medication from US WorldMed for this trial and served as a consultant to GW Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lily, and served on an advisory board to Shire in 2006-2007. Dr. Levin also serves as a consultant to Major League Baseball, regarding the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD. Dr. Nunes served on an advisory board for Eli Lily and Company in January 2012. Drs. Nunes, Sullivan and Bisaga receive medication from Alkermes for ongoing studies that are sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Post completion of this trial Dr. Sullivan has taken a position at Alkermes.

Drs. Mariani, Carpenter, Pavlicova, Mr. Glass, Mr. Brooks and Ms. Mahony report no competing interests and no financial relationships with commercial interests.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. American Psychiatric Association (APA). [Google Scholar]

- Allsop DJ, Copeland J, Lintzeris N, Dunlop AJ, Montebello M, Sadler C, Rivas GR, Holland RM, Muhleisen P, Norberg MM, Booth J, McGregor IS. Nabiximols as an agonist replacement therapy during cannabis withdrawal: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:281–291. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi G, Cooper ZD, Haney M. Subjective, cognitive and cardiovascular dose-effect profile of nabilone and dronabinol in marijuana smokers. Addict Biol. 2013;18:872–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amar M. Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Fearer S, Walker DD, Stanger C, Thostenson J, Grabinski M, Bickel WK. An initial trial of a computerized behavioral intervention for cannabis use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Rocha HL, Higgins ST. Clinical trial of abstinence-based vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:307–316. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.4.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94:1311–1322. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, McDowell D, Brooks DJ, Cheng WY, Levin FR. A preliminary trial: double-blind comparison of nefazodone, bupropion-SR, and placebo in the treatment of cannabis dependence. Am J Addict. 2009;18:53–64. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, Nich C, Jatlow P, Bisighini RM, Gawin FH. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:177–187. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD, Haney M. Opioid antagonism enchances marijuana's effects in heavy marijuana smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1875-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker SE, Frankforter T, Babuscio T, Nich C, Ball SA, Carroll KM. Assessment concordance and predictive validity of self-report and biological assay of cocaine use in treatment trials. Am J Addict. 2014;23:466–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2014.12132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Kranzler HR, Brown J, Korner PF. Assessment of medication compliance in alcoholics through UV light detection of a riboflavin tracer. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1412–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Liddle H, Titus JC, Kaminer Y, Webb C, Hamilton N, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, William JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders- Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser AD, Meatherall R. Lack of interference by nabilone in the EMIT d.a.u. cannabinoid assay, Abbott TDx cannabinoid assay, and a sensitive TLC assay for delta 9-THC-carboxylic acid. J Anal Toxicol. 1989;13:240. doi: 10.1093/jat/13.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, DeSantis SM, Kryway E, Hartwell KJ, McRae-Clark AL, Brady KT. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine in cannabis-dependent adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:805–812. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Cooper ZD, Bedi G, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Foltin RW. Nabilone decreases marijuana withdrawal and a laboratory measure of marijuana relapse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1557–1565. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Reed SC, Foltin RW. Effects of THC and lofexidine in a human laboratory model of marijuana withdrawal and relapse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Nasser J, Bennett A, Zubaran C, Foltin RW. Marijuana withdrawal in humans: effects of oral THC or divalproex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:158–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Ward AS, Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Effects of oral THC maintenance on smoked marijuana self-administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;67:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Singleton EG, Liguori A. Marijuana Craving Questionnaire: development and initial validation of a self-report instrument. Addiction. 2001;96:1023–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967102312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD. The COMBINE SAFTEE: a structured instrument for collecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the alcoholism field. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2005:157–167. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.157. discussion 140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, Wiegand F, Mao L, Beyers K, McKay A, Ait-Daoud N, Anton RF, Ciraulo DA, Kranzler HR, Mann K, O'Malley SS, Swift RM. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007;298:1641–1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberger L, Rubin A, Wolen R, DeSante K, Rowe H, Forney R, Pence P. Pharmacokinetics, metabolism and drug-abuse potential of nabilone. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9(Suppl B):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin FR, Mariani J, Brooks DJ, M. P, Cheng C, Nunes E. Dronabinol for the treatment of cannabis dependence: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin FR, Mariani J, Brooks DJ, Pavlicova M, Nunes EV, Agosti V, Bisaga A, Sullivan MA, Carpenter KM. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of venlafaxine-extended release for co-occurring cannabis dependence and depressive disorders. Addiction. 2013;108:1084–1094. doi: 10.1111/add.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1986;22:343–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani JJ, Brooks D, Haney M, Levin FR. Quantification and comparison of marijuana smoking practices: Blunts, joints, and pipes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall K, Gowing L, Ali R, Le Foll B. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD008940. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008940.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae AL, Budney AJ, Brady KT. Treatment of marijuana dependence: a review of the literature. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:369–376. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Quitkin FM, Donovan SJ, Deliyannides D, Ocepek-Welikson K, Koenig T, Brady R, McGrath PJ, Woody G. Imipramine treatment of opiate-dependent patients with depressive disorders. A placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:153–160. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2014. [July 22, 2015]. 2014.) Available online at http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Kimmerling A, Doebrick C, Kosten TR. Effects of lofexidine on stress-induced and cue-induced opioid craving and opioid abstinence rates: preliminary findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:569–574. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption in Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg K, Roffman R, Carroll K, McRee B, Babor T, Miller M, Kadden R, Duresky D, Stephens R. Brief Counseling for Marijuana Dependence. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Adler LA, Weiss MD, Michelson D, Ramsey JL, Moore RJ, Renard D, Brady KT, Trzepacz PT, Schuh LM, Ahrbecker LM, Levine LR. Atomoxetine treatment of adults with ADHD and comorbid alcohol use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.