Abstract

The differentiation of F9 teratocarcinoma cells mimics the formation of a mouse embryonic tissue, the primitive endoderm. In vitro, small aggregates of F9 cells, termed embryoid bodies, differentiate in response to retinoic acid and develop a surface epithelium that is characterized by the production of α-fetoprotein. In the present study, cellular auto-fluorescence profiles obtained by fluorescence-activated cell sorting demonstrated that undifferentiated embryoid bodies were composed of a single type of cell. In contrast, retinoic acid-induced embryoid bodies were composed of two cell types: a major population displaying autofluorescence levels similar to those of cells from undifferentiated embryoid bodies and a second population displaying higher autofluorescence. RNA analyses demonstrated that the transcription of α-fetoprotein was associated only with the more highly autofluorescent population, indicating that flow cytometry provides a novel mechanism for the separation of undifferentiated cells from differentiated endoderm cells in F9 embryoid bodies.

Key terms: α-Fetoprotein, autofluorescence, differentiation, embryonal carcinoma cells, fluorescence-activated cell sorting, retinoic acid, visceral endoderm

At the blastocyst stage of development in the mouse, an epithelium, the primitive endoderm, differentiates over the surface of the inner cell mass, which alone will give rise to definitive embryonic tissues (21). Tissues derived from the primitive endoderm, the visceral and parietal yolk sacs, will provide vital support for the developing mouse embryo. Because of the small size of the blastocyst, which is 100 μm in diameter and composed of approximately 128 cells, it is difficult to isolate substantial quantities of primitive endoderm. The same difficulties are encountered in attempts to isolate derivatives of the primitive endoderm, visceral endoderm or parietal endoderm, from late blastocyst stage embryos. The need for substantial quantities of tissues for molecular and cell biological analysis has prompted investigators to turn to model systems of early mammalian development. The best characterized system for the in vitro differentiation of the early extraembryonic tissues of the mouse is teratocarcinoma cells.

In suspension culture, aggregates of cells from the F9 teratocarcinoma line form spherical structures known as embryoid bodies (16). Addition of the morphogen retinoic acid (RA) to such cultures induces a differentiation event, the formation of an outer epithelium on the surface of the embryoid bodies (22). This outer epithelial layer expresses urokinase-type plasminogen activator and cytokeratins Endo A and Endo B (1, 11, 15). Embryonically, these markers are expressed by the primary endoderm and the visceral endoderm; accordingly, it is generally accepted that the outer epithelium of differentiated embryoid bodies is endodermal in nature. The secreted glycoprotein α-fetoprotein (AFP), which functions as a carrier of hormones and charged molecules, is also expressed by the visceral endoderm in the embryo (9, 12). In RA-induced embryoid bodies, both AFP protein and transcripts have been localized uniquely to the outer endodermal cells (3, 11, 19). Isolation of cell types from embryoid bodies would provide the means to identify novel cell-specific products whose expression could be assayed in either the inner cell mass or endoderm of the blastocyst. This approach would provide valuable in-sights into the mechanism of early differentiation in the mouse embryo.

Commonly used separation techniques, such as cell panning and cell isolation by means of magnetic beads, rely on a cell-type-specific antibody for selecting the cells to be collected. Other methods rely on intrinsic characteristics of the cells, such as separation by density in Percoll gradients. This technique has been used to isolate endoderm cells from differentiated embryoid bodies (6). In this report we describe differences in autofluorescence between cells in RA-induced embryoid bodies and demonstrate that cell types in differentiated embryoid bodies can be separated by flow cytometry according to these differences. Differences in cellular autofluorescence have been used previously to discriminate between various cell types, including alveolar macrophages from other accessory cells in the human lung and blood monocytes from alveolar macrophages (8, 17). This sorting protocol offers the advantage over density-based separation that any number of parameters, such as cell size, cellular autofluorescence, and external and internal cellular morphology, can be used solely or in combination for the separation of cell types. In addition, the precision of electronic collection is greater than that generally achieved by the manual collections of cells from gradients. We also purified intact steady-state RNA from the isolated cell populations and confirmed the identity of the two populations by the expression of AFP, an endoderm-specific marker, on RNA blots.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Differentiation

Monolayer cultures of the mouse F9 cell line (5) were maintained on 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Falcon Labware, Oxnard CA) coated with 0.1% gelatin (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) F9 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 20 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), 100 U/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco/BRL), and 10−4 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). Monolayer cultures were passaged every two to three days.

For the production of embryoid bodies, F9 monolayers were trypsinized (0.05% trypsin in the presence of 0.02% EDTA), and the cell suspension was seeded onto 100-mm bacteriological petri dishes (Fisher Scientific, Santa Clara, CA) Cell aggregates formed and within one to two d developed into spherical aggregates that grew suspended in the F9 medium. These embryoid bodies remained undifferentiated until they were induced to form an endodermal epithelium by culturing for 8d in F9 medium with the addition of 5 × 10−8 M RA (Sigma). Suspension cultures of embryoid bodies were fed every one to two d.

Histology

For histology, undifferentiated and RA-induced embryoid bodies were fixed for 1 h to overnight in 2% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fixed embryoid bodies were dehydrated by sequential incubation in 50, 70, 90, and 100% ethanol. Dehydrated embryoid bodies were embedded in Polaron Embedding medium (Energy Beam Sciences, Inc., Agawam, MA). Four-micrometer sections were stained with Gill’s No. 5 hematoxylin and 0.6% eosin containing 0.1% phyloxine. Slides were viewed on an inverted Zeiss microscope and were photographed with Kodak Tri-X 400 ASA film.

Antibodies and Immunocytochemistry

A rabbit polyclonal serum against mouse AFP was obtained from ICN Immunobiologicals (Lisle, IL). A fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody was obtained from Sigma.

For immunocytochemistry, embryoid bodies were fixed in 99:1 ethanol:acetic acid (20), dehydrated through 100% ethanol and xylene(s), embedded in paraffin at 56°C, and sectioned. Rehydrated slides were incubated in PBS with 10% milk proteins (Carnation nonfat dry milk, Carnation Co., Los Angeles, CA) to reduce non-specific, background fluorescence. Samples were incubated with the anti-AFP polyclonal antibody diluted 1:40 in PBS plus 10% fetal calf serum for 1 h at ambient temperature, washed three times in PBS plus 10% fetal calf serum, then incubated for 45 min at ambient temperature in a 1:30 dilution of the fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Samples were washed three times in PBS plus 10% fetal calf serum before viewing. Immunofluorescence was observed and photographed with a Zeiss microscope equipped with epifluorescence.

Preparation of Cells for Flow Cytometry

Cells were isolated from two types of embryoid bodies for cell sorting: unlabeled embryoid bodies and embryoid bodies labeled with fluorescein conjugated to isothiocyanate (FITC). Labeling of embryoid bodies involved washing them once with PBS and then resuspending the approximately 300–500 μl of packed embryoid bodies in 10 ml of PBS to which FITC-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA-FITC, Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The labeled embryoid bodies were washed once with an excess of PBS before dissociation to remove unbound WGA-FITC. WGA-FITC-labeled embryoid bodies were dissociated to a single cell suspension by incubation for 5 min at 37°C in 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA and by gentle trituration. Trypsinization was stopped by the addition of medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were collected by centrifugation (5 min, 250g clinical centrifuge, International Equipment Co., Needham, MA) and were resuspended in PBS and filtered once through 43 μm nylon mesh to remove clumped cells in preparation for flow analysis and sorting. Cell suspensions of unlabeled F9 undifferentiated embryoid bodies and unlabeled RA-induced embryoid bodies were prepared in the same way as controls for establishing sorting parameters.

Flow Cytometry

Cell preparations were analyzed and sorted by using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) model 440 (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) equipped with a 5 W argon ion laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) elliptical focusing lens and a 70-μm nozzle orifice. The 488 nm line of the laser was used to excite the fluorescein with 400 mW of laser power. A 530 nm/30 nm width band pass filter (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) was used to filter the emitted fluorescence. Acquisition was triggered on forward scatter with a size threshold selected to minimize small debris. An unlabeled F9 sample was used to set an autofluorescence baseline and to establish forward and orthogonal scatter parameters. Three data parameters, forward and orthogonal scatter and fluorescence, were collected in the list mode and were analyzed by the software program Electric Desk (Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA) to establish appropriate sort windows. Sorting was done by using an 11 -drop delay with three deflected drops to maintain high purity. A FACScan (Becton Dickinson) was used to re-analyze the purity of sorted populations.

RNA Analysis

Upon collection of 100,000–500,000 cells into PBS, the sorted fractions of cells were centrifuged (10 min, 250g), and total RNA from the cell pellet was immediately extracted by the guanidine isothiocyanate-cesium gradient procedure (7) Total RNA from the fetal and adult livers of ICR mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) was extracted in the same manner and used as a positive and negative control, respectively, on RNA blots RNA concentrations were determined by absorbance at 260 nm. RNAs were fractionated on a 1.5% agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde and transferred to nitrocellulose. A 969 basepair insert isolated from a full length cDNA encoding mouse AFP (gift of Dr. S. Tilghman, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ) was labeled via the random priming reaction (18) and used to hybridize to RNA blots. RNA blots were washed at standard stringency (0.3 M NaCl at 65°C). Kodak XAR-5 film was used for autoradiography. RNA loading on gels was quantified by densitometric scanning of RNA blots hybridized with a probe specific for human triose phosphate isomerase (gift of Dr. H. Mohrenweiser, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA). The expression of AFP was also quantified by scanning multiple exposures of RNA blots.

RESULTS

Morphological and Immunocytochemical Characterization of Embryoid Body Differentiation

Histological analyses revealed that undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies were composed of a uniform cell type (Fig. 1A,C). When induced to differentiate for 8 d in the presence of RA, the embryoid bodies produced an outer epithelial layer that was clearly demarcated from the core of the embryoid body (Fig. 1B,D). Cells in the core of RA-induced embryoid bodies morphologically resembled the cells in undifferentiated embryoid bodies (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the outer endoderm cells of RA-induced embryoid bodies displayed a novel morphology, that of a pseudostratified columnar epithelium. In addition, immunofluorescence assays demonstrated that only cells in this outer epithelium expressed the endoderm-specific, secreted glycoprotein AFP (Fig. 2).

Fig 1.

Morphology of undifferentiated and RA-induced embryoid bodies. A: Bright-field photograph of undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies. B: Bright-field photograph of RA-induced embryoid bodies. In C and D embryoid bodies were embedded in plastic, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. C: Undifferentiated embryoid bodies D: RA-induced embryoid body. Size bar for A and B shown in 9. Size bar for C and D shown in D. Bar = 40 μm.

Fig. 2.

Immunocytochemical detection of AFP expression. Embryoid bodies were fixed in acidified ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and stained with a polyclonal antibody specific for AFP. A: Undifferentiated F9 embryoid body. B: RA-induced embryoid body. Bar = 20 μm.

Flow-Cytometric Analysis of Unlabeled F9 Embryoid Bodies

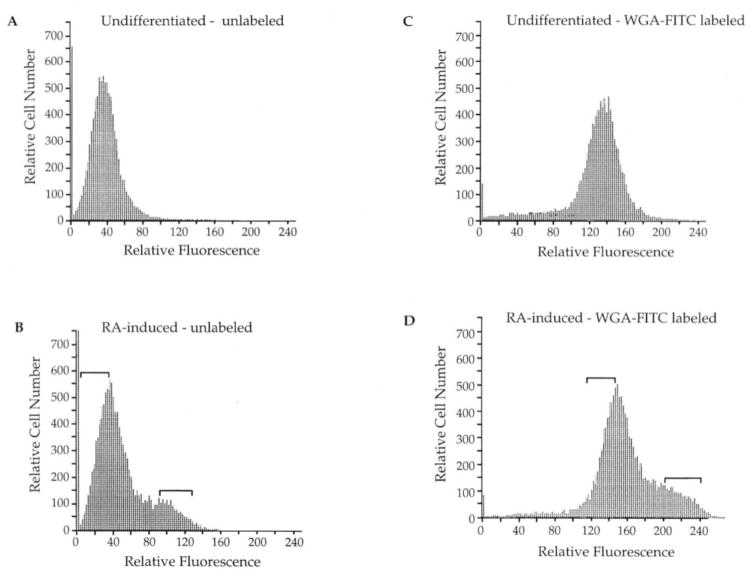

Differences in cellular morphology between core cells and endoderm cells were also apparent during flow-cytometric analyses. These cytometric analyses revealed that cells from undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies displayed a uniform level of relatively low autofluorescence, and the distribution of these cells was described by a simple Gaussian curve (Fig. 3A). The autofluorescent profile of cells from RA-induced samples showed low autofluorescence, similar to that of undifferentiated cells, but an additional peak of higher autofluorescence was also present (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence profiles of unlabeled and WGA-FITC-labeled embryoid bodies. Cellular fluorescence measurements are presented on a single-parameter logarithmic display. A: Autofluorescence profile of cells from unlabeled, undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies. B: Autofluorescence profile of cells from unlabeled, RA-induced embryoid bodies. C: Fluorescence profile of cells from WGA-FITC-labeled, undifferentiated embryoid bodies. D: Fluorescence profile of two cell populations from WGA-FITC-labeled, RA-induced embryoid bodies. These profiles were taken from a single collection; however, the same profiles were reproducible over all collection periods. The small signal in the left corner of histograms represents debris resulting from trypsinization of the samples. Brackets indicate sorting windows for the collection of cells.

Flow-Cytometric Analysis of WGA-FITC-Labeled F9 Embryoid Bodies

In other experiments, embryoid bodies were labeled with WGA-FITC before dissociation. WGA-FITC binds N-acetyl glucosamine residues, and staining of embryoid bodies with this FITC-labeled lectin allows the fluorescent signal from cells to be better separated from that of debris present as a result of trypsinization. (The majority of debris is represented by the fluorescent signal adjacent to the Y-axis in Fig. 3.) Cytometric analyses demonstrated that WGA-FITC-labeled undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies were composed of a single cell type that displayed a unimodal curve upon analysis. WGA-FITC-labeled RA-induced embryoid bodies were composed of two cell types, one with a relatively lower fluorescent signal and one with a relatively higher one. These profiles are similar to those of unlabeled embryoid bodies and indicate that, although the WGA-FITC label was added before dissociation, this regimen appears to have raised the level of fluorescence detected on all cell types (both inner and outer). The gate settings used for sorting unlabeled populations based on autofluorescent signals, and labeled populations based on total fluorescent signals, are indicated on the histograms.

These sorting profiles were highly reproducible. Details from the cytometric analysis of four separate experiments are presented in Table 1. Through multiple trials, the level of fluorescence (indicated by the peak position along the X-axis) of the low and high fluorescent populations in RA-induced embryoid bodies remained constant (Table 1A). In addition, the proportion of cells that were present in one peak compared with the other remained constant (Table 1B). Therefore, the fluorescent profiles were an innate characteristic of the differentiated cells that composed the embryoid bodies.

Table 1.

Analysis of FACS Profiles

| A. Peak positions in unstained vs. FITC-labeled cells (relative fluorescence units) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment no. | Unlabeled

|

FITC-labeled

|

||

| Low | High | Low | High | |

| 1 | 59 | 108 | 150 | 211 |

| 2 | 42 | 106 | 154 | 214 |

| 3 | 39 | 111 | 148 | 209 |

| 4 | 49 | 95 | 155 | 216 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x̄ ± S.D. = | 45 ± 9 | 105 ± 7 | 152 ± 3 | 213 ± 3 |

| B. Distribution of cells in peaks (% of total cells) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment no. | Unlabeled

|

FITC-labeled

|

||

| Low | High | Low | High | |

| 1 | 64.3 | 34.3 | 61.7 | 37.0 |

| 2 | 70.9 | 26.5 | 75.4 | 24.2 |

| 3 | 64.7 | 27.7 | 66.2 | 32.5 |

| 4 | 63.0 | 32.0 | 61.7 | 37.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| x̄ ± S.D. = | 66 ± 4 | 30 ± 4 | 66 ± 4 | 33 ± 6 |

Confirmation of Separation of Cell Populations

To ensure that pure populations of cells were sorted based on our sort windows, we mixed collected samples of low and high fluorescent cells in equal numbers and reanalyzed the sample (Fig. 4). The second analysis clearly demonstrated that the newly mixed sample contained two populations of cells, centered on two fluorescent values separated by approximately 700 units on the X-axis with no overlap (Fig. 4B). As shown by the sorting gates in Fig. 4A, we chose conservative limits for collection of these cell populations (i.e, cells in the region where the two peaks might overlap were not collected). This re-analysis demonstrated the purity provided by our sorting parameters.

Fig. 4.

Confirmation of sorting parameters. The two cell populations collected from WGA-FITC-labeled, RA-induced embryoid bodies were re-analyzed to assess the purity provided by sorting parameters. A: Fluorescence profile of cell populations of WGA-FITC-labeled, RA-induced embryoid bodies before separation and collection. B: Fluorescence profile of the same populations after collected cells were recombined in equal numbers.

RNA Analyses of Cell Populations Isolated by Flow Cytometry

Upon collection of separated cell populations, total RNA was isolated and RNA analyses were performed. To determine the purity of the collected cells, we chose to assay the expression of the endoderm-specific transcript AFP. Because mouse fetal liver is known to express AFP (23), a dilution series of mouse fetal mRNA was included as a positive standard for densitometric scanning (Fig. 5, lanes 1–3), and adult liver, which does not express AFP, was included as a negative control (lane 11). Loading was normalized by densitometric scanning of the triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) signal; TPI is a general cellular metabolic enzyme whose level of transcription does not change with the differentiation of F9 teratocarcinoma cells. The results of the RNA analysis shown in Fig. 5 are representative of multiple experiments. For comparison with sorted populations, RNA isolated from intact undifferentiated and intact RA-induced embryoid bodies were included in the analyses.

Fig. 5.

RNA analysis of AFP and TPI expression. Total RNA was prepared from fetal liver, adult liver, intact embryoid bodies, and sorted cell populations. RNAs were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and hybridized to 32P-labeled AFP cDNA (upper panel) or 32P-labeled TPI cDNA (lower panel). Lane 1: 15 μg of fetal liver RNA; lane 2: 1:4 dilution of fetal liver RNA; lane 3: 1:16 dilution of fetal liver RNA; lane 4: RNA from intact undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies; lane 5: RNA from intact RA-induced embryoid bodies; lane 6: RNA from the low autofluorescent sorted population of unlabeled, RA- induced embryoid bodies; lane 7: RNA from the high autofluorescent sorted population of unlabeled RA-induced embryoid bodies; lane 8: RNA from the low fluorescent sorted population of WGA-FITC-labeled, RA-induced embryoid bodies; lane 9: RNA from the high fluorescent sorted population of WGA-FITC-labeled, RA-induced embryoid bodies; lane 10: empty lane; lane 11: adult liver RNA.

Abundant AFP expression was manifested by intact RA-induced embryoid bodies (approximately 15 μg RNA, Fig. 5, lane 5), whereas AFP expression from undifferentiated F9 embryoid bodies was undetectable by RNA analysis (15 μg RNA, lane 4). Based on densitometric quantification of known RNA standards (fetal and adult liver RNA), our RNA blots can detect between 50 and 100 copies of RNA per cell, per lane. Significantly, after separating WGA-FITC-labeled cells from RA-induced embryoid bodies based on their relative levels of fluorescence, AFP expression was detected only in the more highly fluorescent population (lane 9, approximately μg RNA loaded).

The high autofluorescent population of unlabeled, RA- induced embryoid bodies (lane 7, approximately 1 μg RNA loaded on gel) also showed abundant AFP expression; however, the low fluorescent population (lane 6) did not have detectable RNA present for comparison (see lower panel). RNA from low fluorescent cell populations in unlabeled embryoid bodies was routinely more difficult to obtain in high enough quantities for RNA analyses. This was probably due to the proximity of this cell population to cellular debris during flow sorting. During collection, fragments of cells or other debris may have registered as collection events, thus lowering the expected yield of RNA per cell. Therefore, WGA-FITC-labeling of cells, which moved both the low and high autofluorescent populations farther away from the debris area, was necessary for reproducible isolation of intact RNA from the low autofluorescent population. These results clearly demonstrate that cells expressing AFP can be completely separated from cells not expressing AFP in RA-induced embryoid bodies by flow cytometry.

DISCUSSION

We separated two populations of cells within RA-induced embryoid bodies by flow cytometry. RNA analyses demonstrated that intact steady-state mRNAs could be isolated from sorted populations from WGA-FITC-labeled embryoid bodies. AFP mRNA was detected in only one cell population, the higher autofluorescent population that concomitantly appears with the RA-induced differentiation of embryoid bodies. Numerous studies have demonstrated that AFP protein and mRNA are present only in the endoderm layer of differentiated embryoid bodies (1,3,9,11,12,19). Therefore, we conclude that by successfully separating AFP-expressing cells from cells that do not express AFP, we have separated endoderm cells from core cells based on autofluorescent differences.

Autofluorescence probably reflects such properties as the cell’s protein constitution and the presence of intracellular NADH, riboflavin, flavin coenzymes, flavoproteins, and metabolic rates within the cell (2,4). The visceral endoderm is a specialized absorptive and secretive epithelium; correlating with these functions, outer endodermal cells of embryoid bodies contain numerous pinocytotic and lysosomal vacuoles (10,12). This specialized ultrastructure, along with metabolic differences, may account for the differences in autofluorescence observed between endodermal cells and undifferentiated F9 cells.

To quantify the level of enrichment for cells that express AFP, we performed densitometric analyses (data not shown), in which the level of AFP expression was normalized with respect to the level of expression of a glycolytic gene, TPI. Scans indicated that the normalized level of AFP expression in highly autofluorescent populations was approximately 2.8 fold higher than that in intact RA-induced embryoid bodies. This enrichment approaches the theoretical limit of enrichment for this system, which can be calculated as follows. Highly autofluorescent (endoderm) cells constitute approximately 1/3 of a differentiated embryoid body ( Table 1). In addition, we quantified the number of AFP-positive cells in the outer endoderm in our immunofluorescence assays and in published in situ hybridizations, and determined that approximately 1/3 of outer endoderm cells express AFP mRNA or protein after 8 d of differentiation. Therefore, the fraction of cells expressing AFP in an intact differentiated embryoid body is 1/9. After sorting, within samples of highly autofluorescent cells, 1/3 of these would still be the AFP-expressing cells. Therefore, the theoretical limit for enrichment of AFP-producing cells after sorting based on autofluorescence would be (fraction of cells expressing AFP in sorted populations) ÷ (fraction of cells expressing AFP in intact differentiated embryoid bodies), or (1/3) ÷ (1/9), or 3-fold. This value closely corresponds to our densitometric calculations. In addition, as the RNA blots demonstrated (Fig. 5), collections of the low auto-fluorescent cell population, which corresponds to the core, undifferentiated cells of the embryoid bodies, were not contaminated with cells that expressed AFP. Both the isolated endodermal cells and the undifferentiated cells would provide valuable material for biochemical and molecular analyses. Casanova et al. (6) isolated core cells and endoderm cells on Percoll gradients and demonstrated that endoderm cells expressed AFP after culture. However, they did not show that only one of the two separated populations expressed AFP at the time of isolation, as we have done.

In our analyses, lysates from separate collections were pooled, and the RNA was isolated by cesium gradient centrifugation, which greatly aids in preventing contamination of samples with DNA. In preparations in which ≥ 106 cells were pooled, the yield of RNA was substantially higher than that of the preparations of 500,000 cells. This reduced yield in preparations of low cell number is probably due to the loss of RNA in the cesium gradients during centrifugation. This loss might best be minimized by the addition of carrier RNA when possible (i.e., if RNAs are to be analyzed on RNA blots rather than used for the generation of cDNA).

In conclusion, teratocarcinoma cells have proved to be a valuable resource for identifying gene products such as uvomorulin (E-cadherin), a protein necessary for compaction in the mouse embryo, and genes, such as the REX-1 gene, that respond to RA (13,14). The technical difficulty in obtaining purified tissues from early mouse embryos remains a hindrance to advances in molecular investigations and provides continued impetus for the use of embryonal carcinoma cells as a resource. Novel techniques using these systems, such as the one described here, should facilitate the investigation of gene expression during early mammalian development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Program for Analytical Cytology at UCSF and the Lawrence Livermore Laboratories, an NIEHS Training Grant T32ES07106 (C.A.B., J.J.L.), NIH Grant Po-1 HD26732, and the Office of Health and Environmental Research, US Department of Energy, Contract DE-AC03-76-SF01012. and a research fellowship from the American Heart Association, California affiliate.

We gratefully acknowledge Mary McKenney and Dr. Stephen G. Grant (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) for critical reading of the manuscript and for helpful discussions.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Adamson EA, Grover A. The production and maintenance of a functioning epithelial layer from embryonal carcinoma cells. In: Silver LM, Martin GR, Strickland S, editors. Teratocarcinoma Stem Cells. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1983. pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubin JE. Autofluorescence of viable cultured mammalian cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 1979;27:36–43. doi: 10.1177/27.1.220325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker S, Casanova J, Grabel LB. Localization of endoderm-specific mRNAs in differentiating F9 embryoid bodies. Mech Devel. 1992;37:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(92)90010-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson RC, Meyer RA, Zaruba ME, McKhann GM. Cellular autofluorescence—is it due to flavins? J Histochem Cytochem. 1979;27:44–48. doi: 10.1177/27.1.438504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstine EG, Hooper ML, Grandchamp S, Ephrussi B. Alkaline phosphatase activity in mouse teratoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:3899–3903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casanova JE, Grabel LB. The role of cell interactions in the differentiation of teratocarcinoma-derived parietal and visceral endoderm. Dev Biol. 1988;129:124–139. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chirgwin JM, Przybyla AE, MacDonald RJ, Rutter WJ. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dethloff LA, Lehnert BE. Pulmonary interstitial macrophages: isolation and flow cytometric comparisons with alveolar macrophages and blood monocytes. J Leuk Biol. 1988;43:80–90. doi: 10.1002/jlb.43.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dziadek M, Adamson ED. Localization and synthesis of alphafoeto-protein in post-implantation mouse embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1978;43:289–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman SJ. Functions of extraembryonic membranes. In: Copp AJ, Cockroft DL, editors. Postimplantation Mammalian Embryos. A Practical Approach. IRL Press; New York: 1990. pp. 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grover A, Oshima RG, Adamson ED. Epithelial layer formation in differentiating aggregates of F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1690–1696. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan BLM, Taylor A, Adamson E. Cell interactions modulate embryonal carcinoma cell differentiation into parietal or visceral endoderm. Nature. 1981;291:235–237. doi: 10.1038/291235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosler BA, LaRosa GJ, Grippo JF, Gudas LJ. Expression of REX-1, a gene containing zinc finger motifs, is rapidly reduced by retinoic acid in F9 teratocarcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5623–5629. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyafil F, Morello D, Babinet C, Jacob F. A cell surface glycoprotein involved in the compaction of embryonal carcinoma cells and cleavage stage embryos. Cell. 1980;21:927–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marotti KR, Belin D, Strickland S. The production of distinct forms of plasminogen activator by mouse embryonic cells. Dev Biol. 1982;90:154–159. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin GR. Teratocarcinomas and mammalian embryogenesis. Science. 1980;209:768–776. doi: 10.1126/science.6250214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicod LP, Lipscomb MF, Toews GB, Weissler JC. Separation of potent and poorly functional human lung accessory cells based on autofluorescence. J Leuk Biol. 1989;45:458–465. doi: 10.1002/jlb.45.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigby PWJ, Dieckmann M, Rhodes C, Berg P. Labeling deoxyribonucleic acid to high specific activity in vitro by nick translation with DNA polymerase I. J Mol Biol. 1977;113:237–251. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers MB, Watkins SC, Gudas LJ. Gene expression in visceral endoderm: a comparison of mutant and wild-type F9 embryonal carcinoma cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1767–1777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sainte-Marie G. A paraffin embedding technique for studies employing immunofluorescence. J Histochem Cytochem. 1962;10:250–256. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snell GD, Stevens LC. Early embryology. In: Green EL, editor. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. 2. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1966. pp. 205–245. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strickland S, Mahdavi V. The induction of differentiation in teratocarcinoma stem cells by retinoic acid. Cell. 1978;15:393–403. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilghman SM, Belayew A. Transcriptional control of the murine albumin/α-fetoprotein locus during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5254–5257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]