Abstract

The organization and sequence of genes encoding the α1-proteinase inhibitor (α1PI), a major serine proteinase inhibitor of the mammalian bloodstream, have been compared in several species, including murine rodents (genus Mus). Analysis of gene copy number indicates that amplification of α1PI genes occurred at some time during evolution of the Mus genus, leading to fixation of a family of about three to five genes in several existing species (e.g., M. domesticus and M. saxicola), and only a single gene in others (e.g., M. caroli). A phylogeny for the various mammalian α1PI mRNAs was constructed based upon synonymous substitutions within coding regions. The mRNAs in different murine species diverged from a common ancestor before the formation of the first species lineages of the Mus genus, i.e., about 10–13 million years ago. Thus, α1PI gene amplification must have occurred prior to Mus speciation; gene families were retained in some, but not all, murine species. The reactive center region of the α1PI polypeptide, which determines target protease specificity, has diverged rapidly during evolution of the Mus species, but not during evolution of other mammalian species included in the analysis. It is likely that this accelerated evolution of the reactive center, which has been noted previously for serine proteinase inhibitors, was driven by some sort of a positive Darwinian selection that was exerted in a taxon-specific manner. We suggest that evolution of α1PI genes of murine rodents has been characterized by both modification of gene copy number and rapid reactive center divergence. These processes may have resulted in a broadened repertoire of proteinase inhibitors that was evolutionarily advantageous during Mus speciation.

Keywords: Gene families, mRNA divergence, Alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor

Introduction

A primary feature of the evolutionary process is the modification of both the structure and regulation of protein-encoding genes. Structural changes may result in amino acid sequence alterations that could impact upon the function of the encoded polypeptide; regulatory modifications perturb expression patterns, including developmental timing, cell specificity, and responses to metabolic effectors. In total, these effects generate diversity in gene structure and function among existing species (Wilson et al. 1977; Ohta 1991). A fundamental question pertains to the nature and extent of selection pressures that drive the appearance and fixation of such diversity.

α1-Proteinase inhibitor (α1PI), also called α1-antitrypsin, is a mammalian serine proteinase inhibitor that specifically recognizes trypsinlike proteinases (Travis and Salvesen 1983; Carrell and Travis 1985; Carrell et al. 1987). It is produced almost exclusively in the liver, and is secreted into the bloodstream, where it functions primarily in the control of neutrophil elastase activity (Travis and Salvesen 1983). The molecular elements responsible for liver specificity of α1PI gene transcription have been studied in detail, and a number of cis-acting elements that interact with a variety of DNA binding factors have been identified (Grayson et al. 1988; Monaci et al. 1988; Costa et al. 1989).

The number of α1PI genes per haploid genome varies among mammalian species. Primates, including baboons and humans, contain a single gene (Rosenberg et al. 1984; Kurachi et al. 1981), as do sheep (Brown et al. 1989), rats (Chao et al. 1990), and the mouse species Mus caroli (Berger and Baumann 1985; Latimer et al. 1987; Rheaume et al. 1988). However, multiple genes are found in the mouse species M. domesticus (Hill et al. 1985; Krauter et al. 1986; Borriello and Krauter 1990, 1991), indicating that α1PI gene amplification occurred recently in mammalian evolution.

The tissue specificity of α1PI expression also differs among species. In Mus caroli, the gene is abundantly transcribed in renal tubular epithelial cells in addition to the liver (Berger and Baumann 1985; Latimer et al. 1987; Rheaume et al. 1988); this contrasts sharply with other species, where transcription is predominantly liver-specific (Grayson et al. 1988; Monaci et al. 1988; Costa et al. 1989). Renal α1PI expression in M. caroli is regulated by androgens during postnatal development, while hepatic expression is at the adult level at birth (Latimer et al. 1987).

Primary sequence comparisons among a variety of serine proteinase inhibitors, both within and between mammalian species, have revealed that the reactive center, which determines the inhibitors’ specificity for proteinases, shows a high level of sequence divergence compared to other regions of the protein (Hill et al. 1984; Hill and Hastie 1987; Borriello and Krauter 1990). It has been suggested that this reflects an accelerated rate of evolution that may have occurred in response to some sort of positive Darwinian selection (Hill and Hastie 1987). This may be a general feature of serine proteinase inhibitor evolution.

It is clear, therefore, that the organization, sequence, and expression of α1PI genes have been modified during evolution. In the present study, we have made a detailed comparison of mammalian α1PI genes and their encoded mRNAs. We have placed particular focus on the timing and species specificity of α1PI gene amplification and the extent of reactive center divergence. Our analysis indicates that amplification of the α1PI gene occurred prior to the onset of speciation within the Mus genus; evolution of the genus was characterized by modification of the size of this primordial gene family. In addition, we find that rapid divergence of the reactive center, a process driven by positive Darwinian selection, occurred among Mus species, but not among other mammals. Thus, selective forces driving evolution of the reactive center have been exerted in a taxon-specific manner.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice of species M. domesticus (strain C57BL/6J) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mus hortulanus, Mus spretus, and Mus caroli were obtained from Dr. Verne Chapman (Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY). Mus cervicolor, Mus cookii, Mus saxicola, and Mus pahari were provided by Dr. Michael Potter under terms of a contract between the National Cancer Institute and Hazleton Laboratories. All animals were used at 2–4 months of age.

Southern Blot Analysis of α1PI Gene Organization

DNA was extracted from the livers of mice representing each of the Mus species by the methods of Sampsell and Held (1985). Samples containing 10 µg DNA were digested with EcoRI, and the resulting fragments were fractionated on 1.0% agarose gels, transferred to a nylon filter, and hybridized to an α1PI-specific probe overnight at 65°C in buffer containing 4 × SSC (1× SSC = 0.015 M sodium citrate, 0.15 M sodium chloride, pH 7.0); the membrane was washed for 2 h at 65C in buffer containing 2 × SSC, and for 30 min in buffer containing 0.5 × SSC. The probe was the cDNA insert of plasmid pCR12, which is a 503-bp PstI fragment of an α1PI cDNA isolated from M. domesticus strain BALB/c (Rheaume et al. 1988).

Cloning and Sequencing of an α1PI cDNA from M. saxicola

A cDNA library was prepared from liver mRNA of M. saxicola in the vector λgt10 (Chaudhuri et al. 1991). Phage clones containing cDNAs corresponding to α1PI mRNAs of M. saxicola were isolated from the library using plasmid pCR12 as probe. The 1.4-kb cDNA of one phage was subcloned into pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene, Inc.), generating plasmid pCR173; it was sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method (Sanger et al. 1977). Sequencing was facilitated by construction of nested deletions generated with exonuclease III (Henikoff 1984), resulting in a number of overlapping sequences. About two-thirds of the sequence was verified on both strands.

To screen for reactive center heterogeneity among M. saxicola α1PIs, 87 additional cDNA clones, and a 1 µl aliquot of each phage stock was grown overnight as a single plaque on a lawn of E. coli C600 cells; the plaques were transferred to nylon filters (Benton and Davis 1973) and hybridized to an end-labeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the reactive center region of pCR173 (nucleotides 1,147–1,166; see Fig. 2). The cDNA inserts in the nonhybridizing clones were amplified by asymmetric-PCR using primers corresponding to the vector/ insert junctions of λgt10; the single-stranded products were sequenced with a primer representing residues 1,093–1,112, which is just outside the reactive center. (See Fig. 2.) Oligonucleotides corresponding to newly identified reactive centers were hybridized to the nylon filter containing the collection of phage clones. This process was continued until all 87 clones were accounted for.

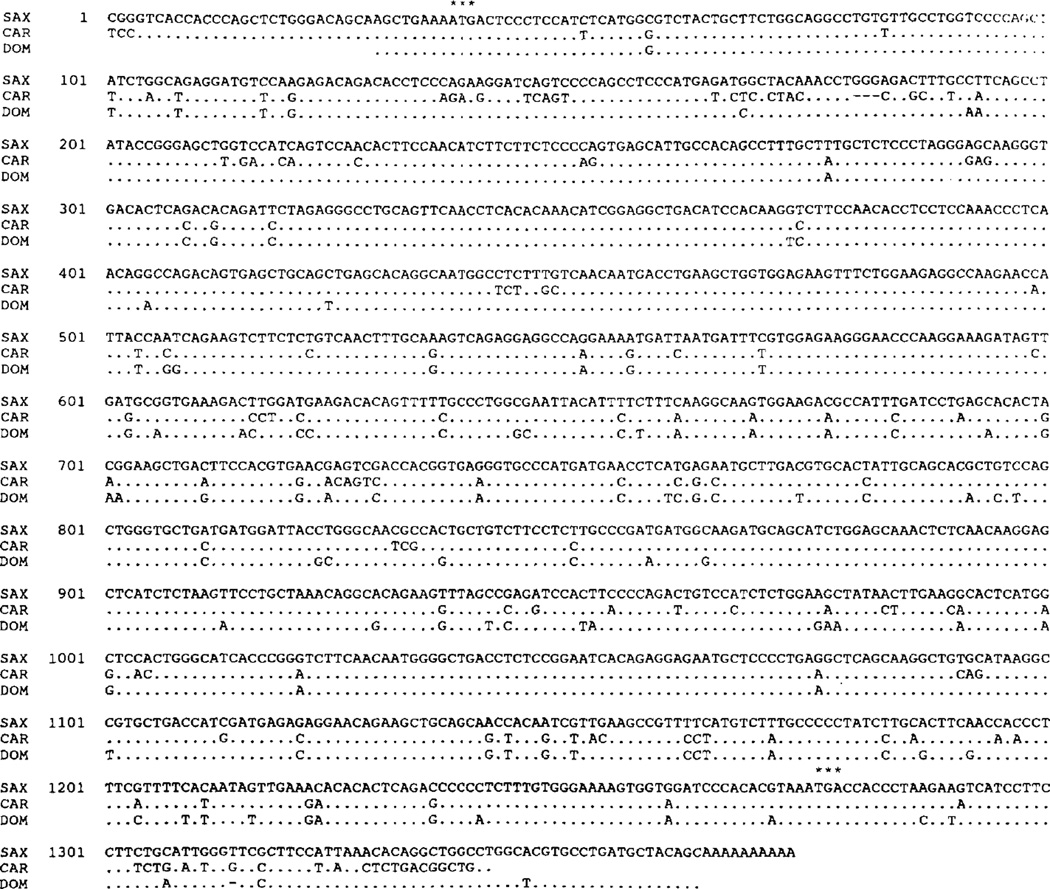

Fig. 2.

Sequences of α1PI cDNAs in Mus species. The sequence of the M. saxicola (SAX) α1PI cDNA is shown aligned with those of M. caroli (CAR; Latimer et al. 1990) and M. domesticus (DOM; Sifers et al. 1990). Numbering is based on the M. saxicola sequence. Differences relative to M. saxicola are indicated; identities are depicted by dots (.) and deletions by dashes (−). Asterisks (*) mark the translational initiation codon at nucleotides 37–39 and the termination codon at nucleotides 1276–1278.

Computer analysis of mammalian α1PIs was done using the sequence analysis software package of the Genetics Computer Group (Devereux et al. 1984). Synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates (KS and KA, respectively) were calculated using a program developed by Li et al. (1985); this program was provided by Dr. W.-H. Li. Phylogenetic trees were constructed from distance matrices and were based upon KS values; branch lengths were determined by the method of Fitch and Margoliash (1967), as described by Li (1981).

Results

α1PI Gene Copy Number in Mus Species

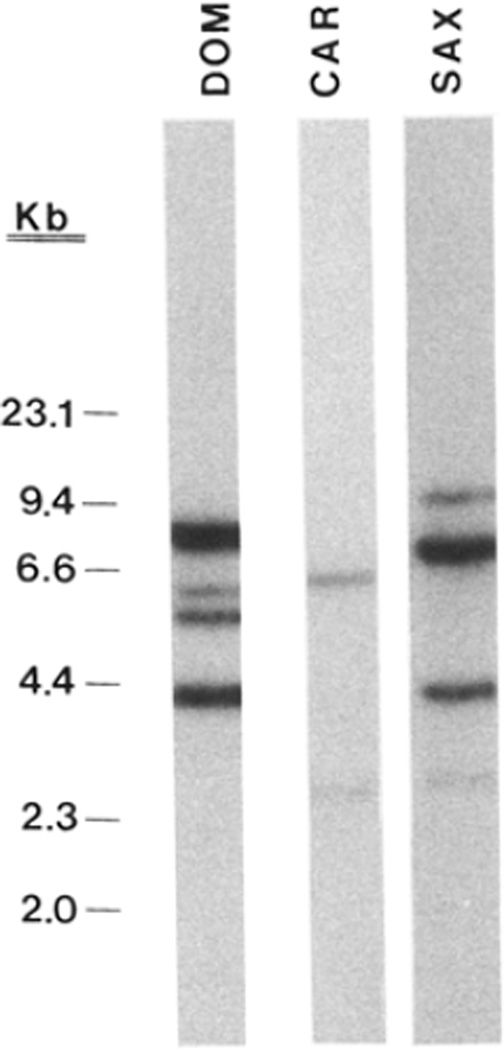

Previous studies indicated that the number of functional α1PI genes varies among mammalian species; inbred strains of M. domesticus contain five genes (Hill et al. 1985; Boriello and Krauter 1990, 1991) while M. caroli, rats, sheep, and primates contain only one (Kurachi et al. 1981; Rosenberg et al. 1984; Berger and Baumann 1985; Latimer et al. 1987; Rheaume et al. 1988; Brown et al. 1989; Chao et al. 1990). To obtain a rough estimate of α1PI gene copy number in the species M. saxicola, which is derived from a lineage that separated early in Mus evolution (Tseng-Crank and Berger 1987; Jouvin-Marche et al. 1988), genomic DNAs were digested with EcoRI and analyzed by Southern blotting. The probe, a 503-bp PstI cDNA fragment (see Materials and Methods), spans a single EcoRI site within the M. domesticus and M. caroli α1PI genes and should hybridize to two DNA fragments totaling a length of about 9 kb (Rheaume et al. 1988; Latimer et al. 1990). As seen in Fig. 1, M. domesticus and M. saxicola exhibited four to six relatively intense bands that represent a total of about 22–35 kb of DNA. In contrast, M. caroli contains two light-intensity bands that represent a total of about 9 kb of DNA. Since it is known that M. domesticus contains five α1PI genes (Hill et al. 1985; Krauter et al. 1986; Boriello and Krauter 1990, 1991), and M. caroli contains only one (Latimer et al. 1990), we estimate that there are approximately three to five genes in M. saxicola. The presence of multiple α1PI genes in both M. domesticus and M. saxicola, which separated from each other 9–10 Mya (Tseng-Crank and Berger 1987; Jouvin-Marche et al. 1988), suggests that amplification of the gene may have occurred early in the evolution of the Mus genus, leading to the fixation of multigene families in separate species.

Fig. 1.

Southern blot analysis of α1PI genes in Mus species. Liver DNA (10 µg) from each of several species was digested with EcoRI, and resulting fragments were fractionated on agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to 32P-labeled α1-PI-specific probe. (See Materials and Methods.) The lanes are M. domesticus strain C57BL/6J (DOM); M. caroli (CAR); M. saxicola (SAX). Each lane contains DNA from a single animal; all were run on the same blot. Size markers are HindIII fragments of λ DNA, and are indicated to the left.

Sequence Analysis of α1PI cDNAs from M. saxicola

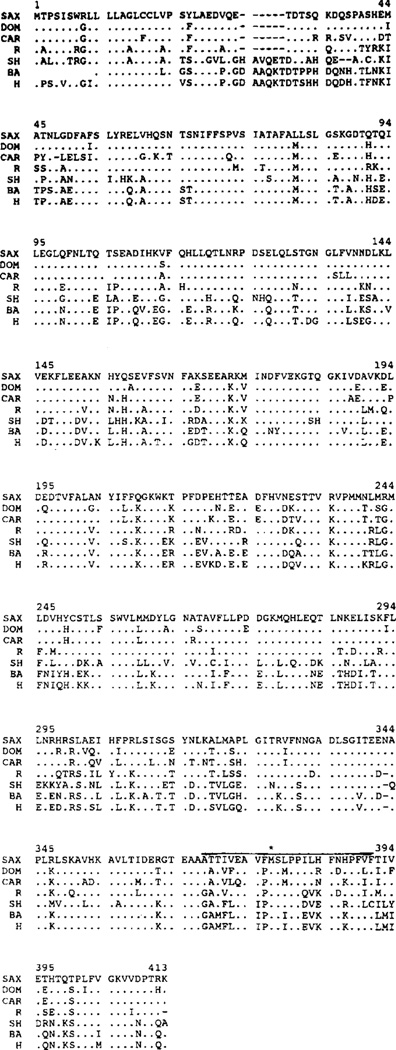

To verify and extend the conclusions drawn from Southern blot analysis, we conducted a more detailed analysis of the α1PI gene family in M. saxicola. A cDNA library was prepared from M. saxicola liver mRNA and screened for α1PI clones; plasmid pCR173, containing a 1.4-kb α1PI cDNA, was isolated and sequenced (Fig. 2). Alignment with the sequences from other Mus species (Sifers et al. 1990; Latimer et al. 1990) indicated 91% identity between M. domesticus and M. caroli, 92% identity between M. domesticus and M. saxicola, and 88% identity between M. caroli and M. saxicola. The amino acid sequences for seven mammalian α1PIs are compared in Fig. 3. Among the Mus sequences, there is 85% identity between M. domesticus and M. caroli, 85% between M. domesticus and M. saxicola, and 81% between M. caroli and M. saxicola; similarities (Gribskov and Burgess 1986) are 92%, 93%, and 89%, respectively, indicating that about half of the amino acid substitutions are chemically conservative. It was rather surprising to find that the Mus α1PI mRNAs are equally divergent from one another. The M. saxicola lineage separated from the others about 8–10 Mya, while the M. domesticus and M. caroli lineages diverged about 4–6 Mya (Tseng-Crank and Berger 1987; Jouvin-Marche et al. 1988); thus, one would have expected the M. domesticus and M. caroli sequences to be more closely related to each other than either is to M. saxicola. The near-equal extents of divergence among the three species indicate that their α1PI genes radiated from a common ancestor at about the same time.

Fig. 3.

Amino acid sequences for mammalian α1PIs. The sequence of the α1PI of M. saxicola (SAX) is shown aligned with those of M. domesticus (DOM; Sifers et al. 1990), M. caroli (CAR; Latimer et al. 1990), rat (R; Chao et al. 1990), sheep (SH; Brown et al. 1989), baboon (BA; Kurachi et al. 1981), and human (H; Rosenberg et al. 1984). Numbering is based on M. saxicola. Identities are indicated by dots (.) and deletions by dashes (−). The reactive center is overlined. An asterisk (*) marks the P1 amino acid at residue 377.

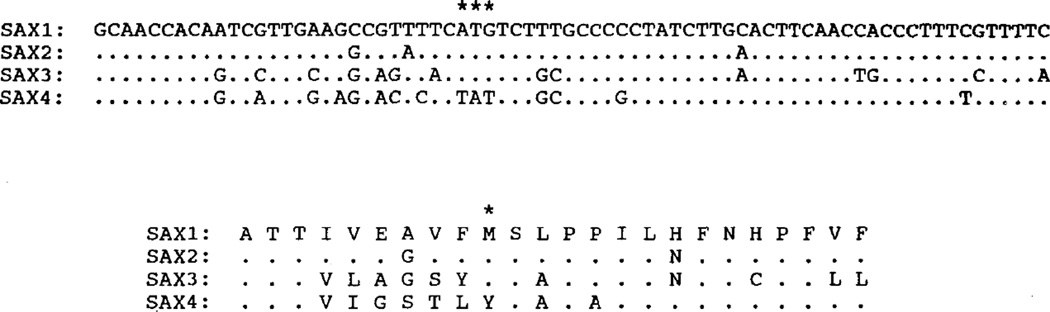

The reactive center regions of a number of α1PI clones from the cDNA library were sequenced. It was expected that this region would be hypervariable among the α1PI genes within M. saxicola, so the number of distinct reactive center sequences should be an indicator of the size of the family in this species. Indeed, this type of analysis was used to define α1PI gene copy number in M. domesticus (Boriello and Krauter 1990). An oligonucleotide corresponding to the reactive center section of pCR173 (nucleotides 1,147–1,166; see Fig. 2) was hybridized to a filter containing 87 α1PI cDNA phage clones. Only 31 of the 87 clones hybridized to this oligonucleotide; in contrast, all of the clones hybridized to an oligonucleotide corresponding to a region just 5’ to the reactive center. This suggests that the M. saxicola mRNAs are particularly divergent within their reactive centers. In a control experiment, an oligonucleotide corresponding to the reactive center region of the M. caroli α1PI mRNA hybridized to all α1PI-specific cDNA phage clones isolated from a M. caroli library. Thus, as expected for a species with a single α1PI gene, M. caroli does not show reactive center heterogeneity.

One of the M. saxicola clones that did not hybridize to the reactive center oligonucleotide of pCR173 was chosen for further analysis. PCR amplification, followed by direct sequencing, led to identification of a distinct reactive center in this clone. An oligonucleotide corresponding to this region was found to hybridize to 13 clones, none of which hybridized to the first oligonucleotide. Through additional cycles of oligonucleotide hybridization and PCR amplification/sequencing of nonhybridizing clones, we identified two more reactive center sequences: the third corresponded to 38 clones while the fourth corresponded to five clones. Thus, based upon reactive center sequences, we could classify the 87 cDNAs of M. saxicola into four groups (Fig. 4), indicating the existence of at least four α1PI genes in this species. This is consistent with conclusions drawn from the Southern blot experiments. (See Fig. 1.) The four mRNAs are currently being sequenced in their entirety. Partial sequences obtained thus far (R. Goodwin, unpublished) indicate that the M. saxicola gene family, like that in M. domesticus (Boriello and Krauter 1991), exhibits a high degree of sequence divergence within the reactive center region.

Fig. 4.

Sequences of the reactive centers of M. saxicola α1PIs. The four reactive center regions deduced from analysis of 87 cDNA clones (see text) are aligned in the upper panel, with asterisks (*) indicating the codon that corresponds to the P1 amino acid. Amino acid sequences for the reactive centers are aligned in the lower panel, with the P1 amino acid indicated by an asterisk. Sequence differences are highlighted; identities are indicated by dots (.).

Origin of the Murine α1PI Gene Family

We used the extent of synonymous substitution to more accurately determine the evolutionary relationships among the various α1PI mRNAs. Since synonymous base substitutions within the coding regions of mRNAs do not affect amino acid sequences, they are generally considered to be selectively neutral, and accumulate at a constant rate over time. Thus, the number of synonymous changes between two sequences is a measure of the time since they shared a common ancestor (Kimura 1977; Jukes and King 1979; Li et al. 1985). Nonsynonymous substitutions, on the other hand, change amino acid sequences and are subject to selective constraints upon protein function (Kimura 1977; Li et al. 1985).

We determined the numbers of both synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions in pairwise comparisons of representative α1PI mRNA coding regions of eight mammalian species, including four within the genus Mus. Using a computer program developed by Li et al. (1985), we calculated KS (the number of synonymous changes per synonymous site) and KA (the number of nonsynonymous changes per nonsynonymous site) for each pairwise comparison among the α1PI sequences (Table 1). The mean KA/KS ratio for the 28 comparisons was 0.37 ± 0.14. It was not surprising to find that KS > KA, since synonymous substitutions are well tolerated, while nonsynonymous changes are under purifying selection (Kimura 1977; Jukes and King 1979; Li et al. 1985). Indeed, the KA/KS ratios for 34 different mRNAs in a variety of mammalian species, as tabulated by Li et al. (1985), averaged 0.22 ± 0.12, and ranged from 0.030 to 0.47; this wide range primarily reflects large variations in rates of evolution at nonsynonymous sites (Li et al. 1985).

Table 1.

Number of substitutions per synonymous site and per nonsynonymous site among mammalian α1 PI mRNAsa

| DB6 | DC | Car | Sax | R | Sh | Ba | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB6 | — | 0.041 (0.009) |

0.082 (0.010) |

0.075 (0.009) |

0.12 (0.012) |

0.25 (0.019) |

0.22 (0.018) |

0.22 (0.017) |

| DC | 0.13 (0.032) |

— | 0.086 (0.014) |

0.12 (0.017) |

0.16 (0.019) |

0.28 (0.028) |

0.26 (0.022) |

0.26 (0.022) |

| Car | 0.15 (0.026) |

0.14 (0.035) |

— | 0.11 (0.011) |

0.15 (0.014) |

0.26 (0.020) |

0.24 (0.018) |

0.23 (0.018) |

| Sax | 0.13 (0.02) |

0.17 (0.038) |

0.16 (0.027) |

— | 0.12 (0.012) |

0.23 (0.012) |

0.23 (0.012) |

0.23 (0.012) |

| R | 0.32 (0.041) |

0.32 (0.058) |

0.36 (0.045) |

0.26 (0.036) |

— | 0.22 (0.017) |

0.19 (0.016) |

0.19 (0.016) |

| Sh | 0.92 (0.10) |

1.06 (0.28) |

0.89 (0.099) |

0.91 (0.10) |

0.86 (0.092) |

— | 0.18 (0.015) |

0.18 (0.015) |

| Ba | 0.82 (0.093) |

0.83 (0.13) |

0.71 (0.081) |

0.70 (0.079) |

0.83 (0.093) |

0.62 (0.073) |

— | 0.038 (0.006) |

| H | 0.85 (0.096) |

0.76 (0.12) |

0.76 (0.089) |

0.72 (0.082) |

0.85 (0.095) |

0.58 (0.067) |

0.11 (0.021) |

— |

Values for KS (below diagonal) and KA (above diagonal), in substitutions per site, were determined using a computer program developed by Li et al. (1985); standard errors are given in parentheses. The following species were analyzed: Mus domesticus inbred strains C57BL/6 (DB6) and BALB/c (DC); Mus caroli (Car); Mus saxicola (Sax); rat (R); sheep (Sh); baboon (Ba); and human (h). All sequences were from the literature (Rosenberg et al. 1984; Kurachi et al. 1981; Brown et al. 1989; Chao et al. 1990; Hill et al. 1984; Sifers et al. 1990; Latimer et al. 1990), except that for M. saxicola, which was determined in the present work (Fig. 1). Comparisons were made for the entire coding region (428 codons, see Fig. 2); for strain BALB/c, they were made for the C-terminal 213 codons, since only that region of the mRNA has been sequenced (Hill et al. 1984)

The KS values obtained from the six pairwise comparisons among the four murine α1PI mRNAs were very similar (Table 1). This is clearly distinct from what is predicted based upon the phylogeny of the species themselves: M. saxicola separated from M. domesticus and M. caroli about 8–10 Mya; M. caroli separated from M. domesticus about 4–6 Mya (Tseng-Crank and Berger 1987; Jouvin-Marche et al. 1988); the two M. domesticus inbred strains were established in laboratory colonies less than a century ago (Festing 1989). Indeed, other genes that have been analyzed in these species, including RP2 and Odc, have diverged in concert with the species themselves (Chaudhuri et al. 1991; Johannes and Berger 1993).

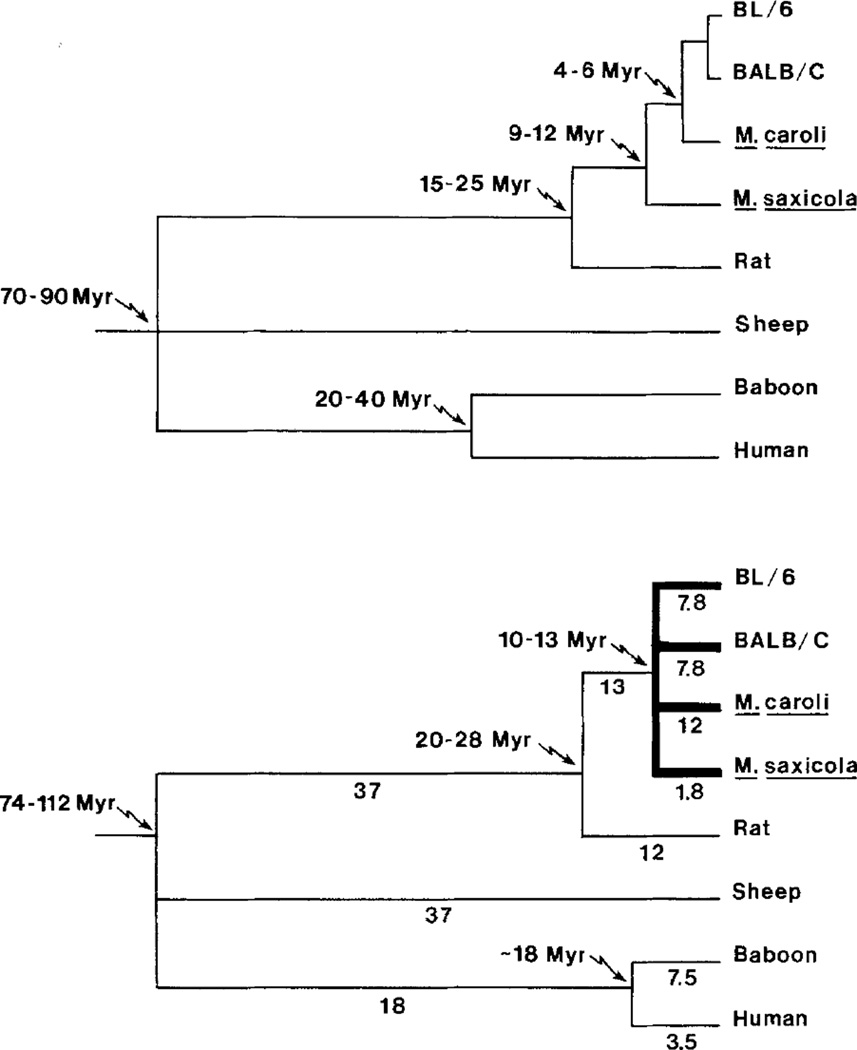

To determine when the α1PI multigene family arose, we utilized the KS values in Table 1 to calculate the separation times for the various mRNAs. Evolutionary rates of 6.5 × 10−9 changes/site/year for rodent lineages, and 3.0 × 10−9 changes/site/ year for sheep and primate lineages were assumed in these calculations; these represent average rates derived from analysis of a number of mammalian genes (Li et al. 1987). The divergence times are presented in Table 2, and the corresponding phylogeny is shown in the lower panel of Fig. 5. Separation of the rat, sheep, and primate sequences parallels divergence of the species themselves, indicating that these mRNAs are products of a single allelic α1PI gene that is evolving in a conventional fashion. In contrast, the four Mus sequences radiated from a common ancestor about 10–13 Mya (Fig. 5), which is the approximate time of formation of the first lineages leading to existing Mus species (Tseng-Crank and Berger 1987; Jouvin-Marche et al. 1988); as mentioned above, this pattern of mRNA divergence does not parallel Mus phylogeny. The results, in total, suggest that amplification of the α1PI gene occurred prior to the time of formation of the first species lineages of the Mus genus; existing murine species have fixed various members of this primordial family.

Table 2.

Divergence times among mammalian α1PI mRNAsa

| Species pair | Divergence time |

|---|---|

| DB6 vs DC | 10.0 |

| vs Car | 11.5 |

| vs Sax | 10.0 |

| vs R | 24.6 |

| vs Sh | 96.8 |

| vs Ba | 86.3 |

| vs H | 89.5 |

| DC vs Car | 10.8 |

| vs Sax | 13.1 |

| vs R | 24.6 |

| vs Sh | 112 |

| vs Ba | 87.4 |

| vs H | 80.0 |

| Car vs Sax | 12.3 |

| vs R | 27.7 |

| vs Sh | 93.7 |

| vs Ba | 74.7 |

| vs H | 80.0 |

| Sax vs R | 20.0 |

| vs Sh | 95.8 |

| vs Ba | 73.7 |

| vs H | 75.8 |

| R vs Sh | 90.5 |

| vs Ba | 87.4 |

| vs H | 89.5 |

| Sh vs Ba | 103 |

| vs H | 96.7 |

| Ba vs H | 18.3 |

The species are listed in Table 1. For each species pair, the divergence time (in Myr) was calculated from the equation td = KS/(r1+ r2) where td is the divergence time, KS is the fractional number of synonymous substitutions (in changes/site) as taken from Table 1, and r1 and r2 are evolutionary rates (in changes/ site/year) for lineages leading to the two species. The evolutionary rate used for rodent lineages was 6.5 × 10−9 while that used for sheep and primate lineages was 3.0 × 10−9 (Li et al. 1987)

Fig. 5.

Phylogeny of mammalian α1PI mRNAs. The evolutionary relationships among mammalian species are shown in the upper panel, along with estimated times of divergence as determined primarily from the fossil record (Li et al. 1985; Tseng-Crank and Berger 1987; Britten 1986; Jouvin-Marche et al. 1988). BL/6 and BALB/C represent inbred strains C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ, respectively, of M. domesticus. The phylogeny of α1PI mRNAs is shown in the lower panel, and is based upon the synonymous substitution rates in Table 1; branch lengths (in changes/100 sites) are indicated. The thick line highlights the relationships among mRNAs of Mus species. (See text for details.)

Rapid Evolution of the α1PI Reactive Center Specifically Within the Mus Genus

Several studies have shown that the reactive centers of serine proteinase inhibitors, including α1PI, have been subjected to a positive Darwinian selection that has accelerated the rate of evolution of this region of the protein (Hill et al. 1984; Hill and Hastie 1987; Laskowski et al. 1987; Boriello and Krauter 1990, 1991). However, analyses to date have not indicated whether this phenomenon has occurred in all mammalian lineages. To determine if rapid reactive center evolution is taxon-specific to any degree, we measured the extents of divergence in this region among eight species for which appropriate sequence data are available.

The coding regions of the α1PI mRNAs were divided into two domains: domain 1 spans the region between codons 367 and 387, and includes the reactive center (Boriello and Krauter 1990, 1991); domain 2 includes the 366 N-terminal codons. (See Fig. 2.) For each of the 28 pairwise comparisons among the eight mammalian species, the KAs for domains 1 and 2 (termed KA1 and KA2, respectively) were calculated and expressed relative to the KS for domain 2 (termed KS2). The ratio KA1/KS2 measures the rate of amino acid replacement in the reactive center relative to the overall neutral rate of α1PI mRNA evolution. A ratio <1 would indicate that the amino acid replacement rate is less than the neutral rate, suggesting a selection against amino acid substitutions in the reactive center region. Conversely, a ratio >1 would indicate that the amino acid replacement rate exceeds the overall neutral rate; such would be consistent with the existence of a positive, or diversifying, selection. Table 3 shows that the KA1/KS2 ratios for mammalian α1PIs averaged 0.79 ± 0.49. Interestingly, the average ratio for murine species was much higher than for the other mammalian species. While the ratios for Mus sequences averaged 1.48 ± 0.40, those for rat, sheep, and primate sequences averaged 0.27 ± 0.068 (Table 3). The reactive centers of human and baboon are, in fact, identical (Fig. 3, Table 3). Thus, within the genus Mus, the α1PI reactive center has accumulated amino acid replacements more rapidly than have other regions of the inhibitor. This has not occurred in other mammalian species, indicating that the phenomenon is taxon-specific. The fact that KA1/KS2 > 1 for all comparisons among the murine species suggests the existence of a positive selection pressure driving the accumulation of amino acid replacements in the reactive center region.

Table 3.

Divergence of the reactive center region of α1PI mRNAsa

| DB6 | DC | Car | Sax | R | Sh | Ba | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DB6 | — | 0.21 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| DC | 1.20 | — | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.35 |

| Car | 1.00 | 1.39 | — | 0.63 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.33 |

| Sax | 1.54 | 2.17 | 1.56 | — | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| R | 0.68 | 1.24 | 0.78 | 1.12 | — | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| Sh | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.33 | — | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| Ba | 0.55 | 0.90 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.19 | — | 0.38 |

| H | 0.53 | 0.95 | 0.38 | 0.77 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.00 | — |

The species are listed in Table 1. For each species pair, the following values were calculated: KA1, the fractional number of nonsynonymous substitutions in domain 1 (the reactive center region, i.e., codons 367–387); KS2, the fractional number of synonymous substitutions in domain 2 (codons 1–366); and KA2, the fractional number of nonsynonymous substitutions in domain 2. The KA1/KS2 ratios are shown below the diagonal, while the KA2/KS2 ratios are shown above the diagonal

The KA2/KS2 ratios, reflecting the amino acid replacement rate throughout most of the α1PI molecule relative to the neutral rate, averaged 0.35 ± 0.095 among the eight mammalian species (Table 3). The mean ratios were 0.45 ± 0.14 among Mus species and 0.29 ± 0.063 among the others. Thus, most of the amino acid coding region is under negative selection and does not show an overall high rate of accumulation of nonsynonymous substitutions, as does the reactive center.

Discussion

Earlier studies had shown that inbred strains of M. domesticus contain five α1PI genes (Hill et al. 1985; Krauter et al. 1986; Borriello and Krauter 1990, 1991). In contrast, only a single gene exists in the murine species M. caroli, as well as in rats, sheep, and primates (Rosenberg et al. 1984; Kurachi et al. 1981; Brown et al. 1989; Chao et al. 1990; Berger and Baumann 1985; Latimer et al. 1987). Thus, at some time during evolution of the Mus genus, α1PI gene amplification occurred, and led to fixation of a gene family in M. domesticus. Southern blotting experiments (Fig. 1) indicate that M. saxicola, like M. domesticus, contains multiple α1PI genes. Sequence analysis of the reactive center regions of cDNA clones corresponding to α1PI mRNAs of M. saxicola led to the identification of four distinct genes in this species (Fig. 4). It is thus clear that a family of genes has been fixed in at least two distantly related Mus species.

Two scenarios might explain the presence of α1PI multigene families in both M. domesticus and M. saxicola. It is possible that amplification of the α1PI gene occurred several times during evolution of the Mus genus, and thus the gene families present in existing species arose independently. Alternatively, α1PI gene amplification may have predated Mus speciation, occurring prior to formation of lineages leading to existing Mus species; subsequent evolution of the genus could have resulted in a multigene family in some species (e.g., M. domesticus and M. saxicola), but not in others (e.g., M. caroli). This second possibility is consistent with the phylogeny of the α1PI mRNAs (Fig. 5), which indicates that the mRNAs in different murine species diverged from a common ancestor before separation of the first lineages leading to current Mus species. This suggests that α1PI gene amplification did occur prior to Mus speciation, so existing species contain what are essentially evolutionary remnants of this primordial gene family.

If, in fact, an α1PI gene family was already present in the pre-Mus population, then how did interspecies variations in gene copy number originate? Perhaps the progenitor Mus population was polymorphic with regard to the number of α1PI genes; during speciation different haplotypes from this population were fixed. Gene copy number polymorphisms do exist within species (Takenaka et al. 1991; Zhu et al. 1991), presumably resulting from unequal crossover events during replication. According to this model, species lineages leading to M. domesticus and M. saxicola derived from ancestors with multiple genes, while the lineage leading to M. caroli derived from ancestors having a single gene. However, it is also possible that all existing Mus species are derived from progenitors containing multiple α1PI genes. Species-specific modifications of gene copy number may have occurred within particular lineages following their isolation. Thus, M. domesticus and M. saxicola retained the gene family inherited from this population, while M. caroli lost all but one gene.

Several studies have demonstrated that the reactive centers of serine proteinase inhibitors have evolved at an accelerated rate, driven by a positive Darwinian selection (Hill et al. 1984; Hill and Hastie 1987; Laskowski et al. 1987; Boriello and Krauter 1990). Such a mode of evolution was initially demonstrated for α1PI and Spi-2 genes; the latter encode α1-antichymotrypsin in the human, contrapsin in the mouse, and a serine proteinase inhibitor of unknown specificity in the rat (Hill et al., 1984; Hill and Hastie 1987). More recently, Yoon et al. (1987) have identified two members of a novel growth-hormone-regulated serine proteinase inhibitor family that show a high number of amino acid replacements within their reactive centers. Borriello and Krauter (1990, 1991) have shown that the reactive centers of the five α1PIs in C57BL/6 mice are extensively diverged; this also appears to be the case for the α1PI gene family members of M. saxicola (Fig. 4). The present study indicates that rapid evolution of the reactive centers of mammalian α1PIs is taxon-specific, having occurred in mice, but not in rats, sheep, or primates. However, the phenomenon may not be unique to the Mus genus. Suzuki et al. (1991) have pointed out that rabbit and guinea pig α1PIs, which are also encoded by small multigene families, show extensive divergence within their reactive centers. Thus, it is likely that both α1PI gene amplification, as well as acceleration of the amino acid substitution rate within reactive centers, occurred in several distinct mammalian lineages. An interesting correlation exists between the presence of multiple α1PI genes and the occurrence of rapid reactive center divergence (Suzuki et al. 1991); the only exception to this is M. caroli (Latimer et al. 1987; Table 3). It may be that gene amplification and rapid reactive center divergence are coupled—i.e., formation of gene families is a prerequisite to increasing the reactive center’s amino acid substitution rate.

A role for positive selection in driving rapid reactive center divergence is implied by the observation that the number of nonsynonymous substitutions within the α1PI reactive center exceeds the number of synonymous substitutions in other regions of the mRNA (Table 3). Thus, the reactive center may have been under a diversifying selection pressure that favored the accumulation of amino acid replacements. The effects of such replacements upon α1PI function are not known. Some of the changes occur at the P1 amino acid (see Fig. 3), which is a critical residue in the determination of target proteinase specificity (Travis and Salvesen 1983); thus, a possible consequence of reactive center divergence might have been alterations in the nature and/or number of proteinases recognized by the inhibitor. Another possibility relates to the observation that the reactive center forms a protruding loop that is highly susceptible to proteolytic attack (Kress and Catanese 1981; Huber and Carrell 1989; Stein et al. 1990). Perhaps divergence within the reactive center offers broadened protection against such attack. It is interesting to note that most of the amino acid replacements within the reactive center have occurred in the region that is N-terminal to the P1 residue (Fig. 4; Boriello and Krauter 1990); this subregion forms the major portion of the protruding loop (Huber and Carrell 1989; Stein et al. 1990).

Hill and Hastie (1987) have suggested that infectious parasites may have been important sources of selection upon the reactive center. These organisms secrete a wide variety of proteolytic enzymes, including serine proteinases, that are involved in invasion of the host and digestion of extracellular proteins within the bloodstream (Banyal et al. 1981; McKerrow et al. 1985; Rosenthal et al. 1989). Amplification of genes encoding proteinase inhibitors, along with acceleration of divergence within their reactive centers, may have provided an effective strategy for combating parasitic invasion. Thus, there may be an evolutionary “interplay” between proteolytic enzymes and proteinase inhibitors, resuliting in rapid coevolution of both classes of proteins (Neurath 1984; Creighton and Darby 1989). Regardless of the exact nature of the selective forces involved, the present study makes clear that such forces were exerted in a taxon-specific manner, driving the evolution of α1PI reactive centers in some, but not all, phylogenetic lineages.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. W.-H. Li for providing the computer program for determining synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions. This work was supported by a grant (DK33886) from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Banyal HS, Misra GC, Gupta CM, Dutta GP. Involvement of malarial proteases in the interaction between the parasite and host erythrocyte in Plasmodium knowlesi infections. J Parasitol. 1981;67:623–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton WD, Davis RW. Screening λgt recombinant clones by hybridization to single plaques in situ. Science. 1973;196:180–182. doi: 10.1126/science.322279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger FG, Baumann H. An evolutionary switch in tissue-specific gene expression: abundant expression of α1-antitrypsin in the kidney of a wild mouse species. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1160–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borriello F, Krauter KK. Reactive site polymorphism in the murine protease inhibitor gene family is delineated using a modification of the PCR reaction (PCR + 1) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5481–5487. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.18.5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borriello F, Krauter KK. Multiple murine α1-protease inhibitor genes show unusual evolutionary divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9417–9421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten RJ. Rates of DNA sequence evolution differ between taxonomic groups. Science. 1986;231:1393–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.3082006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WM, Dziegielewska KD, Foreman RC, Saunders NR, Wu Y. Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of sheep α1-antitrypsin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6398. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell RW, Pemberton PA, Boswell DR. The serpins: evolution and adaptation in a family of protease inhibitors. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:527–535. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrell R, Travis J. α1-antitrypsin and the serpins: variation and countervariation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1985;10:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chao S, Chai KX, Chao L, Chao J. Molecular cloning and primary structure of rat α1-antitrypsin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:323–329. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri AC, Barbour K, Berger FG. Evolution of messenger RNA structure and regulation in the genus Mus: the androgen-inducible RP2 mRNAs. Mol Biol Evol. 1991;8:641–653. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa RH, Grayson DR, Darnell JE. Multiple hepatocyteenriched nuclear factors function in the regulation of transthyretin and α1-antitrypsin genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1415–1425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton TE, Darby NJ. Functional evolutionary divergence of proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors. Trends Biochem Sci. 1989;14:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festing MFW. Inbred strains of mice. In: Lyon MF, Searle AG, editors. Genetic variants and strains of the laboratory mouse. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. pp. 636–648. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch WM, Margoliash E. Construction of phylogenetic trees. A method based on mutational distances as estimated from cytochrome c sequences is of general applicability. Science. 1967;155:279–284. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3760.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson DR, Costa RH, Xanthopoulas KG, Darnell JE. A cell-specific enhancer of the mouse α1-antitrypsin gene has multiple functional regions and corresponding protein-binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1055–1066. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.3.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribskov M, Burgess RR. Sigma factors for E. coli, B. subtilus, phage SPO1, and phage T4 are homologous proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6745–6763. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.16.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III creates targeted breakpoints for DNA sequencing. Gene. 1984;28:351–359. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RE, Hastie ND. Accelerated evolution in the reactive centre regions of serine protease inhibitors. Nature. 1987;326:96–99. doi: 10.1038/326096a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RE, Shaw PH, Barth RK, Hastie ND. A genetic locus closely linked to a protease inhibitor gene complex controls the level of multiple RNA transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:2114–2122. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RE, Shaw PH, Boyd PA, Baumann H, Hastie ND. Plasma protease inhibitors in mouse and man: divergence within the reactive centre regions. Nature. 1984;311:175–177. doi: 10.1038/311175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber R, Carrell RW. Implications of the three-dimensional structure of α1-antitrypsin for structure and function of serpins. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8951–8966. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes GJ, Berger FG. Domains within the mammalian ornithine decarboxylase messenger RNA have evolved independently and episodically. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:555–567. doi: 10.1007/BF00556360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvin-Marche E, Cuddihy A, Butler S, Hansen J, Fitch WM, Rudikoff S. Molecular evolution of a single-copy gene: the immunoglobulin Cκ locus in wild mice. Mol Biol Evol. 1988;5:500–511. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes TH, King JL. Evolutionary nucleotide replacements in DNA. Nature. 1979;281:605–606. doi: 10.1038/281605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. Preponderance of synonymous changes as evidence for the neutral theory of molecular evolution. Nature. 1977;267:275–276. doi: 10.1038/267275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauter KK, Citron BA, Hsu M-T, Powell D, Darnell JE. Isolation and characterization of the α1-antitrypsin gene of mice. DNA. 1986;5:29–36. doi: 10.1089/dna.1986.5.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress LF, Catanese JJ. Identification of the cleavage sites resulting from enzymatic inactivation of human antithrombin III by Crotalus adamanteus proteinase II in the presence and absence of heparin. Biochemistry. 1981;20:7432–7438. doi: 10.1021/bi00529a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurachi K, Chandra T, Friezner-Degen SJ, White TT, Marchioro TL, Woo SL, Davie EW. Cloning and sequence of cDNA coding for α1-antitrypsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6826–6830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski M, Kato I, Kohr WJ, Park SJ, Tashiro M, Whatley HE. Positive Darwinian selection in evolution of protein inhibitors of serine proteases. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:545–553. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer JJ, Berger FG, Baumann H. Developmental expression, cellular localization, and testosterone regulation of α1 antitrypsin in Mus caroli kidney. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12641–12646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer JJ, Berger FG, Baumann H. Highly conserved upstream regions of the α1-antitrypsin gene in two mouse species govern liver-specific expression by different mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:760–769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-H. Simple method for constructing phylogenetic trees from distance matrices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:1085–1089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.2.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-H, Wu C-I, Luo C-C. A new method for estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous rates of nucleotide substitution considering the relative likelihood of nucleotide and codon changes. Mol Biol Evol. 1985;2:150–174. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-H, Tanimura M, Sharp PM. An evaluation of the molecular clock hypothesis using mammalian DNA sequences. J Mol Evol. 1987;25:330–342. doi: 10.1007/BF02603118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKerrow JH, Pino-Heiss S, Lindquist R, Werb Z. Purification and characterization of an elastinolytic proteinase secreted by cercariae of Schistosoma mansoni . J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3703–3707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaci P, Nicosia A, Cortese R. Two different liver-specific factors stimulate in vitro transcription from the human α1-antitrypsin promoter. EMBO J. 1988;7:2075–2087. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath H. Evolution of proteolytic enzymes. Science. 1984;224:350–357. doi: 10.1126/science.6369538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T. Multigene families and the evolution of complexity. J Mol Evol. 1991;33:34–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02100193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheaume C, Latimer JJ, Baumann H, Berger FG. Tissue-and species-specific regulation of murine α1 -antitrypsin gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15118–15121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Barr PJ, Najarian RC, Hallewell RA. Synthesis in yeast of a functional oxidation-resistant mutant of human α1-antitrypsin. Nature. 1984;312:77–80. doi: 10.1038/312077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PJ, McKerrow JH, Rasnick D, Leech JH. Plasmodium falciparum: inhibitors of lysosomal cysteine proteinases inhibit a trophozoite proteinase and block parasitic development. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;35:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampsell BM, Held WA. Variation in the major urinary protein multigene family in wild-derived mice. Genetics. 1985;109:549–568. doi: 10.1093/genetics/109.3.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifers RN, Carlson JA, Clift SM, DeMayo FJ, Bullock DW, Woo SLC. Tissue specific expression of the human alpha-1-antitrypsin gene in transgenic mice. Nuc Acids Res. 1987;15:1459–1475. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifers RN, Ledley FD, Reed-Fourquet L, Ledbetter DH, Ledbetter SA, Woo SLC. Complete cDNA sequence and chromosomal localization of mouse α1-antitrypsin. Genomics. 1990;6:100–104. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PE, Tewkesbury DA, Carrell RW. Ovalbumin and angiotensinogen lack serpin S-R conformational change. Biochem J. 1989;262:103–107. doi: 10.1042/bj2620103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PE, Leslie AGW, Finch JT, Turnell WG, McLaughlin PJ, Carrell RW. Crystal structure of ovalbumin as a model for the reactive centre of serpins. Nature. 1990;347:99–102. doi: 10.1038/347099a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Yoshida K, Sinohara H. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of cDNAs coding for guinea pig α1-antiproteinases S and F and contrapsin. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:928–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka A, Ueda S, Terao K, Takenaka O. Multiple α-globin genes in crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) Mol Biol Evol. 1991;8:320–326. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis J, Salvesen JS. Human plasma protease inhibitors. Ann Rev Biochem. 1983;52:655–709. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng-Crank J, Berger FG. Evolution of steroid-inducible RP2 mRNA expression in the mouse kidney. Genetics. 1987;116:593–599. doi: 10.1093/genetics/116.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AC, Carlson SS, White TJ. Biochemical evolution. Ann Rev Biochem. 1977;46:573–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.003041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J-B, Towle HC, Seelig S. Growth hormone induces two mRNA species of the serine protease inhibitor gene family in rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4284–4289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Vincek V, Figueroa F, Schönbach C, Klein J. Mhc-DRB genes of the pigtail macaque (Macaca nemestrina): implications for the evolution of human DRB genes. Mol Biol Evol. 1991;8:563–578. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]