Abstract

Specialists of developing countries are facing the epidemic growth of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). From 2011 to 2013, I, as a Korean volunteer doctor, had been working in a local primary healthcare center in Bangladesh, assessing rates of NCDs. Proportion of patients with NCDs was increased from 74.96% in 1999 to 83.05% in 2012, particularly due to the spreading of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, and tuberculosis. To succeed in medical mission in developing countries, volunteer doctors have to take measures for preventing chronic diseases along with proper treatment.

Keywords: Volunteers, Developing Countries, Noncommunicable Disease

Graphical Abstract

Many developing countries, including Bangladesh, nowadays confront continuous growth of chronic noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) (1). The epidemic creates challenges for volunteer doctors from high-income countries, who are taking part in international medical missions in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (2). To successfully accomplish medical missions in LMIC, it is crucial to be aware of local medical issues and needs. Healthcare professionals from South Korea are increasingly concerned of global health issues, and many Korean doctors volunteer to serve abroad, which is often realized in the form of short medical missions (one or two weeks). I herein report on my experience of working as a volunteer doctor in Bangladesh for more than 2 years to learn the challenges faced by local medical brigades and find solutions in the management of chronic diseases.

KOREAN VOLUNTEER DOCTOR IN BANGLADESH

Bangladesh-Korea Friendship Hospital is a governmental primary healthcare center in Savar at the outskirts of Dhaka. It was built by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) in 1998 and donated to the Bangladesh government. Since then, KOICA has dispatched physicians specialized in internal medicine every 2 years. The hospital is a 2-story building equipped with 30 beds with specialists of internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics/gynecology, and orthopedic surgery. After local adaptation training, I worked in the hospital from July 2011 to November 2013. The average number of patients referred to me during this period was 206.4 per month and 17.7 per day. I reviewed medical records of patients with communicable diseases (CDs) and NCDs diagnosed in August 2011 - August 2012 to analyze the dynamics of the diseases. Records of out-patient lists, recorded by previous Korean doctors on mission in 1999, were also reviewed.

NCDs ARE A SERIOUS DISEASE BURDEN FOR BANGLADESH

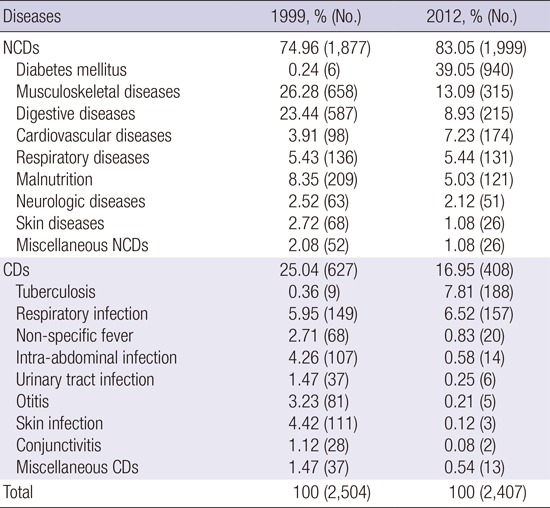

Between 1999 and 2012, proportion of patients with NCDs referred to Korean volunteer doctors increased from 75% to 83%, whereas that of patients with CDs decreased from 25% to 17% (Table 1). In Bangladesh, NCDs are the main causes of mortality (3). NCDs account for 59% of all deaths in Bangladesh (4). In terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), NCDs, including injuries, account for 61% of the total disease burden (5). The underlying causes are modifiable risk factors that are common for all countries (6): tobacco use, inadequate consumption of fruits and vegetables, and physical inactivity. The following rates of risk factors are recorded in Bangladesh: tobacco use in rural males - 52%, urban males - 41%, in rural females - 29%, urban females - 17%; fruits and vegetables consumption among adults - 3.2 and 1.7 per day, respectively; physical inactivity among adults - 35% in males and 64% in females (7).

Table 1. Percentage of noncommunicable and communicable diseases in 1999 and 2012.

| Diseases | 1999, % (No.) | 2012, % (No.) |

|---|---|---|

| NCDs | 74.96 (1,877) | 83.05 (1,999) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.24 (6) | 39.05 (940) |

| Musculoskeletal diseases | 26.28 (658) | 13.09 (315) |

| Digestive diseases | 23.44 (587) | 8.93 (215) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 3.91 (98) | 7.23 (174) |

| Respiratory diseases | 5.43 (136) | 5.44 (131) |

| Malnutrition | 8.35 (209) | 5.03 (121) |

| Neurologic diseases | 2.52 (63) | 2.12 (51) |

| Skin diseases | 2.72 (68) | 1.08 (26) |

| Miscellaneous NCDs | 2.08 (52) | 1.08 (26) |

| CDs | 25.04 (627) | 16.95 (408) |

| Tuberculosis | 0.36 (9) | 7.81 (188) |

| Respiratory infection | 5.95 (149) | 6.52 (157) |

| Non-specific fever | 2.71 (68) | 0.83 (20) |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 4.26 (107) | 0.58 (14) |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.47 (37) | 0.25 (6) |

| Otitis | 3.23 (81) | 0.21 (5) |

| Skin infection | 4.42 (111) | 0.12 (3) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1.12 (28) | 0.08 (2) |

| Miscellaneous CDs | 1.47 (37) | 0.54 (13) |

| Total | 100 (2,504) | 100 (2,407) |

NCD, noncommunicable disease; CD, communicable disease.

Easy access to the hospital improved detection and referral rates of diabetes mellitus in Bangladesh-Korea Friendship Hospital. However, the lacks of diagnostic and therapeutic facilities, such as cardiac catheterization lab, are possibly responsible for the delayed diagnosis and inadequate treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Nearly 90% of Bangladeshis use solid fuel. Many patients suffer from chronic respiratory disease, which is caused by indoor air pollution due to burning of solid fuel and high tobacco use. There are many patients complaining of chronic myalgia and arthralgia; most of them are blue collar workers in the garment factories near the hospital.

Tuberculosis is the only CD which has increased significantly over the last decade. Bangladesh-Korea Friendship Hospital is one of the two governmental medical centers in Savar upazila, providing free anti-tuberculosis treatment under the Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) program. Many patients who cannot afford the cost of the treatment are referred to that hospital.

OBSTACLES TO MEDICAL MISSIONS FROM HIGH-INCOME COUNTRIES

Medical missions of high-income countries offering services to LMICs are intensifying globally (2). Simple surgical interventions and distribution of medicines for acute infectious disease are the main services, which are offered during the short missions. Some experts have raised concerns about unintended consequences of such short volunteer services (8,9,10,11,12,13,14). One of the issues is that patients with chronic NCDs often require sustainable and systematic interventions over a long period.

Although diagnostic and curative standards of NCDs are common worldwide, patients in LMICs are deprived of effective services due to socioeconomic and cultural factors (15). Chronic care of NCDs requires a clear understanding of the patients' values and their active involvement in the management. Foreign doctors are encountering numerous difficulties in the interaction with local patients and healthcare specialists. Unavailability of essential chronic care services hinders the overall management of NCDs (16). The lack of medical equipment, shortage of healthcare providers and weak referral system are among the factors lowering the efficiency of healthcare services.

Paucity of medical records and follow-up data negatively affect continuity of chronic care services. Preventive measures as essential components for controlling chronic diseases (17) are too often neglected. Education level of local patients is inadequate to realize consequences of poor lifestyle. Local health practitioners are also unaware of the importance of lifestyle modifications, and hospitals rarely employ screening tools. Many medical missions pay more attention to treating illnesses rather than preventing them, which is due to the lack of interest and intention to deliver preventative programs.

Inadequate financing is among the main barriers to proper healthcare services in LMICs. Costly repeated consultations for chronic conditions are unaffordable for poor households. Lack of finances is an impediment for regularly purchasing medicines, healthy nutritious food, and covering expenses for transportation.

Foreign doctors on medical mission confront language barriers, leading to poor communication throughout the management of chronic conditions. Many volunteers have little knowledge of the depth of poverty and are unaware of the limits of local medical facilities and healthcare system. Social and cultural factors and contradictions between indigenous and allopathic explanations of ill health question the efficacy of medical services rendered by foreign doctors.

SOLUTIONS FOR SUCCESSFUL AND SUSTAINABLE MEDICAL MISSIONS

To be successful in tackling NCDs, long-term medical missions should prioritize preventive measures. I presented several options for modeling sustainable medical missions (18). Identifying and managing modifiable risk factors are initial key steps toward effective volunteer services. Professionals skilled in addressing community healthcare needs should be recruited to serve in the most vulnerable areas. It is also important to form a team with members from diverse specialist backgrounds capable of working with local community healthcare personnel. Such team should deliver cost-effective, affordable, and feasible services (19). Provision of medicines and technologies should be effectively organized alongside with intensive logistical planning, financial support, training personnel, and institutional support for practitioners. Properly handled individual medical records and arrangements for referrals are important components of long-term care for NCDs. Finally, volunteer specialists should receive extensive pre-departure training with courses of local language and cross-cultural communication.

Without proper preparation and collaboration, medical missions can be seen as self-serving (providing value for only foreign visitors without meeting the local community's needs), ineffective (providing temporary, short-term therapies that fail to address the root causes) and inappropriate (failing to follow current standards of healthcare delivery or public programs) (20). To succeed in a medical mission for LMICs, organizers of the work have to focus more on preventive strategies for NCDs and recruit skilled and experienced professionals capable of supporting local community health personnel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I express my gratitude to the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), Ministry of Foreign Affairs which implements and administers the grant aid and technical cooperation program of the Government of the Republic of Korea. KOICA runs the Korea Overseas Volunteers program. As a participant of this program, medical doctors have been working at a local primary healthcare center in Bangladesh from 1998 to 2015.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Dans A, Ng N, Varghese C, Tai ES, Firestone R, Bonita R. The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in southeast Asia: time for action. Lancet. 2011;377:680–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martiniuk AL, Manouchehrian M, Negin JA, Zwi AB. Brain Gains: a literature review of medical missions to low and middle-income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:134. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahsan Karar Z, Alam N, Kim Streatfield P. Epidemiological transition in rural Bangladesh, 1986-2006. Glob Health Action. 2009;2 doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles, Bangladesh. [accessed on 4 September 2015]. Available at http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/bgd_en.pdf.

- 5.Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global burden of diseases, Bangladesh. [accessed on 4 September 2015]. Available at https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/country_profiles/GBD/ihme_gbd_country_report_bangladesh.pdf.

- 6.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleich SN, Koehlmoos TL, Rashid M, Peters DH, Anderson G. Noncommunicable chronic disease in Bangladesh: overview of existing programs and priorities going forward. Health Policy. 2011;100:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop R, Litch JA. Medical tourism can do harm. BMJ. 2000;320:1017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lluberas G. Medical tourism. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001;12:63. doi: 10.1580/1080-6032(2001)012[0066:mt]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts M. A piece of my mind. Duffle bag medicine. JAMA. 2006;295:1491–1492. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Lassey AT, Danso K. Humanitarian ventures or 'fistula tourism?': the ethical perils of pelvic surgery in the developing world. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:559–562. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfberg AJ. Volunteering overseas--lessons from surgical brigades. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:443–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Tilburg CS. Attitudes toward medical aid to developing countries. Wilderness Environ Med. 1995;6:264–268. doi: 10.1580/1080-6032(1995)006[0264:atmatd]2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green T, Green H, Scandlyn J, Kestler A. Perceptions of short-term medical volunteer work: a qualitative study in Guatemala. Global Health. 2009;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendis S, Al Bashir I, Dissanayake L, Varghese C, Fadhil I, Marhe E, Sambo B, Mehta F, Elsayad H, Sow I, et al. Gaps in capacity in primary care in low-resource settings for implementation of essential noncommunicable disease interventions. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:584041. doi: 10.1155/2012/584041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goudge J, Gilson L, Russell S, Gumede T, Mills A. Affordability, availability and acceptability barriers to health care for the chronically ill: longitudinal case studies from South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher D, Ford N. Action on noncommunicable diseases: balancing priorities for prevention and care. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:547–547A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suchdev P, Ahrens K, Click E, Macklin L, Evangelista D, Graham E. A model for sustainable short-term international medical trips. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:317–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maher D, Ford N, Unwin N. Priorities for developing countries in the global response to non-communicable diseases. Global Health. 2012;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezruchka S. Medical tourism as medical harm to the third world: Why? For whom? Wilderness Environ Med. 2000;11:77–78. doi: 10.1580/1080-6032(2000)011[0077:mtamht]2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]