Abstract

Background

The key pathophysiology of human acquired heart failure is impaired calcium transient, which is initiated at dyads consisting ryanodine receptors (RyR) at sarcoplasmic reticulum apposing CaV1.2 channels at t-tubules. Sympathetic tone regulates myocardial calcium transients through β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) mediated phosphorylation of dyadic proteins. Phosphorylated-RyRs (P-RyR) have increased calcium sensitivity and open probability, amplifying calcium transient at a cost of receptor instability. Given that BIN1 (Bridging Integrator 1) organizes t-tubule microfolds and facilitates CaV1.2 delivery, we explored whether β-AR regulated RyRs are also affected by BIN1.

Methods and Results

Isolated adult mouse hearts or cardiomyocytes were perfused for 5 min with β-AR agonist isoproterenol (1µmol/L) or blockers CGP+ICI (baseline). Using biochemistry and super-resolution fluorescent imaging, we identified that BIN1 clusters P-RyR and CaV1.2. Acute β-AR activation increases coimmunoprecipitation between P-RyR and cardiac spliced BIN1+13+17 (with exons 13 and 17). Isoproterenol redistributes BIN1 to t-tubules, recruiting P-RyRs and improving the calcium transient. In cardiac specific Bin1 heterozygotes (Bin1 HT) mice, isoproterenol fails to concentrate BIN1 to t-tubules, impairing P-RyR recruitment. The resultant accumulation of uncoupled P-RyRs increases the incidence of spontaneous calcium release. In human hearts with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy, we find that BIN1 is also 50% reduced, with diminished P-RyR association with BIN1.

Conclusions

Upon β-AR activation, reorganization of BIN1-induced microdomains recruits P-RyR into dyads, increasing the calcium transient while preserving electrical stability. When BIN1 is reduced as in human acquired heart failure, acute stress impairs microdomain formation, limiting contractility and promoting arrhythmias.

Keywords: cardiomyocyte, dyad, ryanodine receptor, BIN1-microdomain, β-adrenergic system

Introduction

Heart failure is the major cardiac syndrome in the United States, and is a developing epidemic already affecting six million Americans1. The pathological hallmark of HF is a weakened calcium transient2, diminishing contractility3. Normal calcium transient initiates at t-tubules, which are sarcolemmal invaginations enriched with L-type calcium channels (LTCC) containing the pore-forming subunit CaV1.2. LTCCs collect at t-tubule membrane to be in close physical proximity to ryanodine receptors (RyRs) at junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (jSR) membrane, forming LTCC-RyR dyads that facilitate calcium-induced-calcium-release (CICR)4. In failing hearts, gross t-tubule network remodeling occurs and is associated with asynchronous CICR2, 5–7, diminishing calcium transients and impairing contractility. It is not well understood how LTCCs and RyRs physically proximate with each other in healthy heart for efficient CICR, and how such membrane subdomains are altered in heart failure.

Heart failure is a systemic syndrome associated with neurohormonal dysregulation. During heart failure progression, sympathetic tone elevation and abnormal β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) signaling contribute to worsening of cardiac contractile function and electrical instability. In healthy cardiomyocytes, β-AR signals primarily through protein kinase A (PKA), which subsequently phosphorylates both LTCCs8, 9 and RyRs10. Phosphorylation of RyR at its primary PKA target site, Serine 2808 (Ser2808), increases calcium sensitivity and open probability of the receptor11, improving CICR gain yet also contributing to pathologic RyR leak. In heart failure, chronic elevation of sympathetic tone may contribute to hyper-phosphorylated RyRs, and elevation in phosphorylated RyR (P-RyR) at PKA site Ser2808 is associated with calcium overload, impaired contractility and increased arrhythmia10–14. The functional significance of PKA-mediated RyR-Ser2808 phosphorylation has been mechanistically linked to heart failure pathophysiology10–15. In addition, chronic neurohormonal dysregulation is also associated with activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), and the resultant CaMKII-mediated hyper-phosphorylation of RyR at Serine 2814 (Ser2814) also has an important role in heart failure progression15, 16. The mechanisms of RyR phosphorylation in heart failure-related calcium dysregulation remains incompletely understood.

We previously identified that the membrane scaffolding protein bridging integrator 1 (BIN1) facilitates microtubule-dependent LTCC trafficking to T-tubules17, and shapes actin-dependent T-tubule membrane microdomains to regulate ionic flux18. The current study suggests a critical role of BIN1 in β-AR regulated CICR and LTCC-RyR coupling at dyads. We find that five minutes of β-AR activation reorganizes P-RyR association with LTCC-enriched BIN1 microdomains, facilitating EC coupling. Our findings indicate that, in addition to LTCC regulation, BIN1-induced microdomains may regulate the localization of RyR and its hyper-active phosphorylated state at the dyads. The observed BIN1-based regulation of P-RyR is translatable to diseased human hearts. It has been reported that BIN1 is transcriptionally decreased in human and animal models of acquired heart failure7, 19, 20, which also recovers during myocardium recovery19. Here we further identify that in human acquired heart failure with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy, reduced BIN1 results in less association with P-RyR. Thus, when BIN1 is reduced, impaired cardiac contractility20, increased ventricular arrhythmias18, and impaired β-AR response18, can result.

Calcium regulatory and microdomain generating proteins such as BIN117, 18 which decrease with acquired heart failure7, 20 and recover with heart recovery19, are interesting for better understanding the altered organization within failing cardiomyocytes. BIN1 organized microdomains are potential targets for optimizing macromolecular coupling and improving heart function.

Methods

Experimental Animals

All mouse procedures were reviewed and approved by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Cardiac specific Bin1 heterozygotes (Bin1 HT: Bin1flox/+; Myh6-cre+) deleted mice were generated by crossing Bin1flox mice21 with Myh6-cre+22 mice as previously described18. Both male and female young adult mice (10–12 weeks) were used in the study. Each biochemical experimental repeat used sex-matched Bin1 HT and WT mice from the same litter with five to six mice per group. Each cellular experiment represents cardiomyocytes isolated from three to four mice per group.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies used for coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblotting include mouse anti-total RyR (tRyR, Abcam); rabbit anti-RyR-phospho Serine 2808 and anti-RyR-phospho Serine 2814 (Badrilla), rabbit anti-CaV1.2 (Alomone Labs), rabbit anti-β1AR and anti-β2AR (Abcam), mouse anti-BIN1 BAR domain (2F11, Abcam), recombinant monoclonal anti-BIN1 exon 13 (Sarcotein Diagnostics), rabbit anti-BIN1-SH3 (Abcam), rabbit anti-Actin (Sigma). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma unless indicated otherwise.

Coimmunoprecipitation of BIN1 and P-RyR from heart lysates

For coimmunoprecipitation, adult mouse hearts were perfused with normal tyrode buffer (mmol/L: 136 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 5.5 Glucose, 5 HEPES, pH=7.4), containing either 300 nmol/L CGP-20712A and 50 nmol/L ICI 118,551, or 1 µmol/L isoproterenol (ISO) for 5 min. Hearts were homogenized and subsequently solubilized in lysis buffer (mmol/L: 50 Tris pH 8.5, 5 EDTA, 150 NaCl, 10 KCl, 0.75% Triton X-100, 5 NaF, 5 β-glycerophosphate, 1 NaVO3) supplemented with proteinase inhibitors tablet (Roche) for 2 hours at 4 °C. After centrifugation, heart lysate supernatant (3 mg) was incubated with 5 µg appropriate antibodies including mouse anti-GST (IgG control) overnight at 4°C. Samples were incubated with dynabeads (Life technologies) for 30 min at room temperature and washed and eluted in 2× sample buffer.

Cardiomyocyte isolation and immunofluorescence labeling

Ventricular myocytes were isolated as previously described18 and maintained in perfusion buffer for 2 hours, allowing cell attachment to laminin-coated coverslips or 35 mm glass bottom dishes. Cardiomyocytes were treated with either 300 nmol/L CGP-20712A and 50 nmol/L ICI 118,551 or 1 µmol/L isoproterenol for 5 min, followed by fixation in methanol at −20 °C for 5 min and immunofluorescent labeling as previously described18. The primary antibodies used are mouse anti-BIN1-BAR (1:50), rabbit anti-RyR-phospho Serine-2808 (1:200), mouse anti-tRyR (1:100), and rabbit anti-CaV1.2 (1:100). For STORM imaging, freshly made oxygen-scavenging buffer (10 mmol/L cysteamine, 0.5 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 40 µg/mL catalase, 10% glucose in 50 mmol/L Tris with 10 mmol/L NaCl) was used to enable photoswitching according to methods described previously23.

Spinning disc confocal and super resolution STORM imaging

All images were collected using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope with a 100 × objective with 1.49 numerical aperture total internal reflection fluorescent (TIRF) objective and NIS Elements software with STORM module. Confocal Z-stacks at Z-step increment of 0.25 µm were collected using a spinning-disc confocal unit (Yokogawa CSU10) and captured by a high resolution ORCA-Flash 4.0 digital CMOS camera. The STORM images (signals within 500nm Z-depth from the coverslips) were acquired using lasers (488, 561 from a self-contained 4 line laser module with AOTF) and captured by a high speed iXon DU897 Ultra EMCCD camera. Fresh STORM imaging buffer was exchanged every hour to maintain photoswitching properties. The STORM module was used to obtain and analyze the images to generate 3-dimensional (3D) projections of BIN1/P-RyR and BIN1/CaV1.2 images at nanoscale resolution.

3D-STORM image rendering

The native 3D-STORM images are displayed using the Gaussian rendering algorithm available in Nikon Elements software and 3-dimensional stacks of 3D-STORM images (2 channels per acquisition, either BIN1 and CaV1.2 or BIN1 and P-RyR) in tiff format were obtained at a z-spacing of 10 nm for a depth of 500 nm. The stacks were then converted to 2-dimensional bmp images with ImageJ and then imported individually as different planes at the same z-spacing into AutoCAD 2016 (Autodesk). The signal in each plane was then manually traced, then the tracings were autonomously rendered as a vector-based 3D object. A CaV1.2 object was then combined with the BIN1 and RyR objects using BIN1 as the common reference, and each assigned a different semi-transparent color to visualize relative 3-dimensional positioning of the proteins.

Calcium transient measurement

Freshly isolated cardiomyocytes were loaded with 10 µmol/L Cal-520-AM (AAT Bioquest) in 0.4% pluronic F-127 in normal tyrode buffer for 30 min. Cells were washed 3 times in buffer containing 1mmol/L probenecid before placing in the imaging chamber with or without 1 µmol/L ISO for 5 minutes. Cells were then paced with field stimulator (Ionflux) at 1 Hz. Calcium fluorescence was imaged with a spinning disc confocal microscope and images were collected at 67 fps. The fluorescence intensity was analyzed using Nikon Element software. Cells with at least 5 rhythmic calcium transients induced before any spontaneous calcium release were used for calculation of peak calcium transient amplitude. All cells were used in calculation of the percent incidence of spontaneous calcium release.

Signal processing and statistical analyses

Image J was used for fluorescence intensity profile and t-tubule peak intensity analysis. Briefly, an XY frame image was selected at similar focal plane of cardiomyocytes, and a same sized rectangular box was placed at 2 µm below the longitudinal edge to include five representative t-tubules while avoiding interference from sarcolemma, intracellular peri-nuclear area, and intercalated discs. Fluorescent signal within each boxed area was collapsed along the short axis to generate fluorescent profile. The collapsed signals from four t-tubules were then averaged with background subtracted for analysis of t-tubule peak intensity. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS and Stata. Given 5 or 6 hearts in each group for biochemical experiments, we performed Friedman's two-way nonparametric ANOVA in conjunction with the RANK procedure. Use of the blocking variable tested the treatment and genotype effect, as well as gene × treatment interaction effect. For fluorescence intensity data, we first applied square root transformation to normalize the distribution. A Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) model with exchangeable covariance matrix was then used to adjust for correlation among cardiomyocytes from the same heart. Gene × treatment interaction was initially modeled into all the analysis, but was excluded from the final GEE model when it failed to achieve statistical significance. For the comparison of frequency of spontaneous calcium release (SCR), the GEE model with the logit link function was used for the binary response, and ‘heart’ was used as the cluster factor to take the correlation into account. Mann Whitney test was used to compare difference between failing and non-failing human hearts.

Human Studies

De-identified human heart lysates from non-failure and ischemic heart failure patients were obtained from the Cedars-Sinai Heart Institute (CSHI) Biobank, which stores plasma as well as tissue and lysates from heart explants acquired under informed consent using a protocol approved by institutional review board from the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Office of Research Compliance.

Results

BIN1 regulates β-AR dependent phosphorylation of RyR at Ser2808

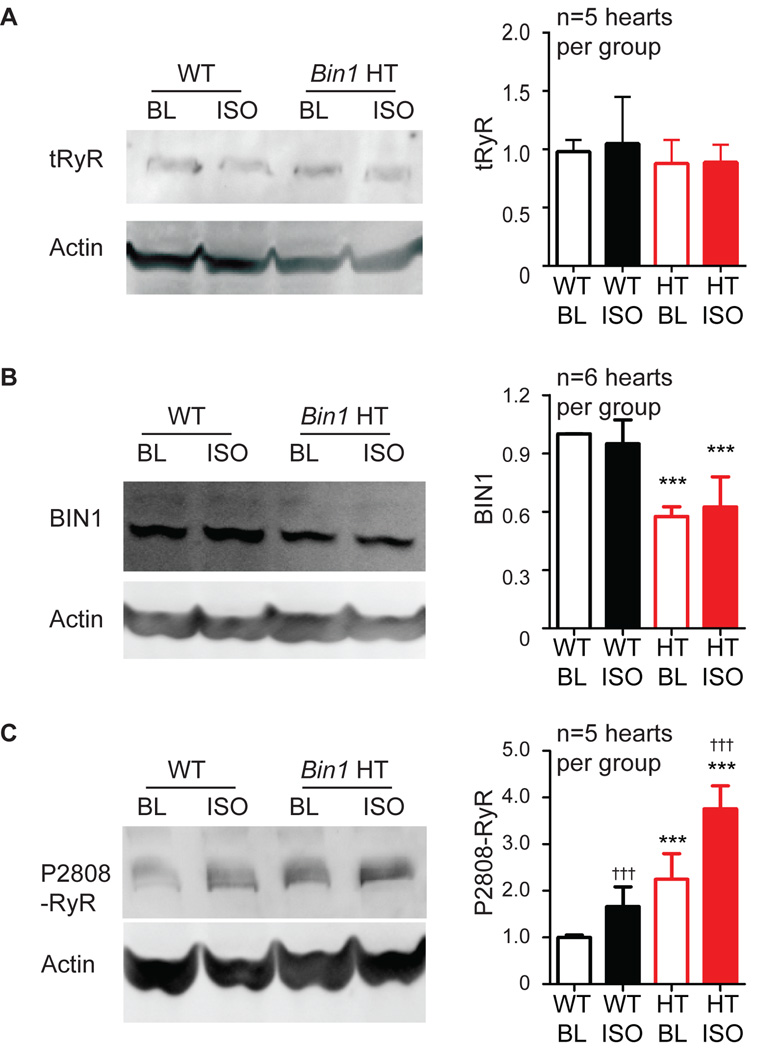

To assess whether BIN1 regulates β-AR induced RyR phosphorylation, we first examined, in both WT and cardiac specific heterozygous Bin1-deleted adult mouse hearts (Bin1 HT, Bin1flox/+; Myh6-Cre+), the effect of acute β-AR activation on RyR expression and phosphorylation at the primary PKA targeted residue Ser2808 (P2808-RyR). Young adult mouse hearts were isolated and retrograde perfused in vitro with physiological buffer. Acute sympathetic activation was induced by including the β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO, 1 µmol/L) for five minutes in the perfusate. Basal sympathetic tone (baseline) was assessed by including β-AR antagonists (CGP-20712A + ICI 118,551). In Bin1 HT hearts, without sympathetic activation, tRyR content is the same (Figure 1A), however cardiac BIN1 is 50% decreased (Figure 1B) and P2808-RyR is significantly increased (Figure 1C). Five minutes of β-AR activation does not alter tRyR or BIN1 content in either WT or Bin1 HT hearts (Figures 1A and 1B), yet is sufficient to increase P-RyR in both genotypes (Figure 1C). No significant gene × treatment interaction effect was observed. These data indicate that both a reduction in BIN1 and ISO-induced β-AR signaling increase phosphorylation of RyRs at PKA-targeted Ser2808 in the heart. The increase in basal phosphorylation of RyR at Ser2808 is not due to changes in β-AR density in Bin1 HT hearts (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of RyR is increased in Bin1 HT hearts, particularly after acute β-AR stimulation. Western blot of tRyR (A), BIN1 (B) and P2808-RyR (C) in whole heart lysates from WT and Bin1 HT hearts at basal tone with endogenous β-AR auto-activity blocked with antagonists (ICI+CGP) or with acute β-AR activation after 5 min 1 µmol/L isoproterenol (ISO) treatment. *** indicates p<0.001 between genotypes; ††† indicates p<0.001 after ISO.

ISO treatment can also activate CaMKII24 which will phosphorylate Ser281425 and, although less likely25, may contribute to P2808-RyR26. Using Ser2814 phosphorylation as a readout, we found that P2814-RyR is neither altered in Bin1 HT hearts at baseline (with β-AR blockers) nor changed in response to 5 min ISO perfusion (Figure S2). Lack of changes in P2814-RyR suggests, with five minutes of ISO, CaMKII may not have time to activate yet. Lack of changes in P2814-RyR indicates that elevated P2808-RyR is primarily due to β-AR activated, PKA mediated phosphorylation at Ser2808.

BIN1 organizes LTCCs and P2808-RyRs at dyads

To explore the role of BIN1 in regulation of phosphorylated receptors, we studied the intracellular distribution of P-RyR relative to BIN1-microdomains in wild type adult mouse cardiomyocytes using super-resolution STORM imaging. STORM is a microscopy technique based on stochastic switching of single-molecule fluorescence signal using fluorescent probes that can switch between fluorescent and dark states (“blinking events”). By taking sufficient acquisitions to capture enough blinking events of individual fluorophores, the center of each fluorophore signal can then be resolved mathematically. In combination with the thin illumination method using lasers delivered at the incident angle slightly smaller than the critical TIRF angle to reduce out-of-focus fluorescence background27, the resultant spatial resolution of each fluorophore within around 600 nm of the focal plane can be accurately reduced to 20 nm at X-Y axis23. The astigmatism method using an astigmatic lens with improved correction of axial chromatic aberration allows us to acquire 3D multicolor STORM image with Z-depth of 800 nm around a focal plane at Z-resolution of 50 nm23.

As indicated in the cartoon in Figure 2A, cell surfaces at the glass coverslip edge were subjected to STORM imaging. Black arrows indicate the cell surface Z-grooves19 lined with t-tubule openings. The two-dimensional (2D) STORM image of BIN1 (red) and P-RyR (green) (Figure 2A) indicates that, near the surface of the cell, P-RyR signal distributes along Z-lines with enrichment at BIN1 clusters. Furthermore, 3D-STORM imaging of single dyads at sub-sarcolemma t-tubules (Figure 2B) reveals that P-RyR clusters (green) are enriched at BIN1-induced basket-like microfolds18 (red). Consistent with previous results17, CaV1.2 channels (blue) cluster at the center of these BIN1 microfolds (Figure 2B, right panels). To understand the three dimensional spatial organization of dyad proteins, microdomain rendering of STORM images of P-RyR/BIN1/CaV1.2 was generated. Images were combined into three channels using BIN1 signal as a common reference point. As seen in Figure 2C, the BIN1 (red) basket-like structures appear to bridge the dyadic cleft, spanning between CaV1.2 channels (blue) at T-tubule membrane and P-RyRs (green) at jSR membrane.

Figure 2.

P2808-RyR is enriched at BIN1-organized dyadic microdomains. (A) 2D-STORM images image of P2808-RyR and BIN1 in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Cartoon identifies the imaged area relative to the whole cardiomyocyte with surface attached to a glass coverslip. Scale bar: 500 nm. (B) 3D-STORM images of P2808-RyR with BIN1 (left two panels) or BIN1 with CaV1.2 (right two panels) in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. (C) 3D-STORM microdomain rendering of P2808-RyR /BIN1/CaV1.2 at dyads. (D) P2808-RyR co-immunoprecipitates with BIN1+13+17. IP: mouse anti BIN1 exon 13; IB: rabbit anti P2808-RyR and BIN1-SH3.

β-AR activation increases BIN1 interaction with P2808-RyR

Based on the suggestion of P-RyR interaction with BIN1 by STORM imaging, we next used biochemical coimmunoprecipitation to test the relationship. Using a recombinant monoclonal antibody against cardiac BIN1 exon 13, we found that P-RyR co-immunoprecipitates with BIN1+13+17 (Figure 2D). Of note, BIN1+13+17 is the BIN1 isoform organizing cardiac T-tubule microdomains18. In WT hearts, ISO treatment does not affect total RyR or total BIN1 protein expression (Figure 1A and 1B), yet the higher amount of ISO-induced P-RyR (Figure 1C) results in higher P-RyR coimmunoprecipitation with BIN1+13+17 (Figure 2D), indicating receptor phosphorylation enhances its binding affinity with BIN1. We then asked whether ISO-enhanced interaction between BIN1 and P-RyR could be altered in hearts with BIN1 deficiency. In Bin1 HT hearts, less BIN1 is associated with less coimmunoprecipitation of P-RyR at baseline and after acute β-AR activation with ISO. In contrast to WT hearts, acute ISO-induced increase in RyR phosphorylation in Bin1 HT hearts (Figure 1C) is not associated with a concomitant increase in P-RyR coimmunoprecipitation with BIN1 (Figure 2D). These results suggest that P-RyR is attracted to BIN1. Once BIN1 is saturated such as in Bin1 HT hearts, no further clustering with P-RyR is possible.

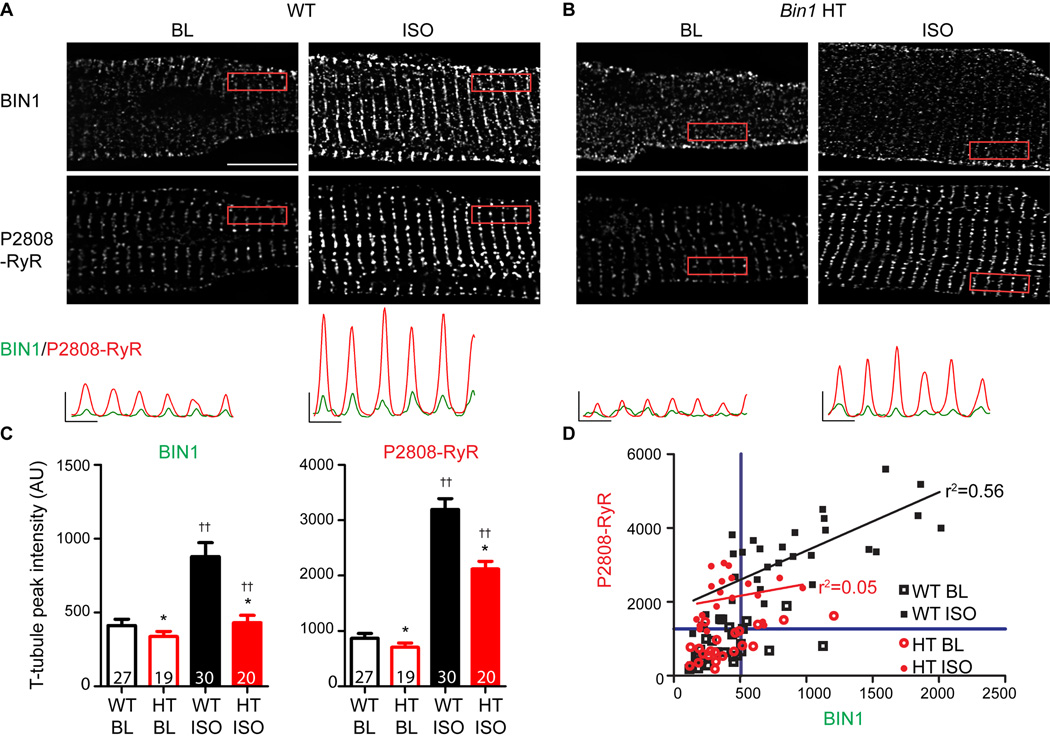

Origin of P2808-RyR recruited to BIN1-microdomains upon β-AR activation

To understand why Bin1 HT hearts lose ISO-enhanced interaction between BIN1 and P-RyR (Figure 2D), we used spinning disc confocal imaging to examine whether rapid intracellular redistribution of BIN1 and P-RyR can occur in response to β-AR stimulation. In isolated WT myocytes, both BIN1 and P-RyR follow a regular t-tubule/jSR distribution pattern, which is less apparent in Bin1 HT myocytes (Figure 3A–B, fluorescent profiles in the bottom panel). Strikingly, only in WT cardiomyocytes, 5 min ISO treatment doubles t-tubule BIN1 along with a significant increase in P-RyR at jSR membrane (Figure 3C), resulting in correlation between t-tubule BIN1 signal and jSR P-RyR (r2=0.56, p<0.001, black line in Figure 3D; baseline: r2=0.11, p=0.09, line not shown). In Bin1 HT myocytes (baseline: r2=0.23, p<0.05, line not shown), ISO fails to increase BIN1 at t-tubules, resulting in less P-RyR and a weak correlation with BIN1 (r2=0.05, p=0.32, red line).

Figure 3.

BIN1 recruits P2808-RyR to dyad upon β-AR stimulation. Representative confocal images of BIN1 (top) and P2808-RyR (bottom) labeling in WT (A) and Bin1 HT (B) cardiomyocytes at baseline (ICI+CGP) and after 5 min treatment with 1 µmol/L ISO. Scale bar: 10 µm. Fluorescent intensity profiles of boxed areas are included at the bottom for BIN1 (green) and P2808-RyR (red). (C) Average peak t-tubule intensity of BIN1 and P2808-RyR from the boxed areas in (A–B) after ISO treatment in WT and Bin1 HT myocytes. (D) Correlation between P2808-RyR intensity at jSR and t-tubule BIN1 intensity in WT and Bin1 HT cardiomyocytes. Blue lines define 75% quartile of both R2808-RyR and BIN1 signals in baseline WT cardiomyocytes. * indicates p<0.05 between genotypes; †† indicates p<0.01 after ISO.

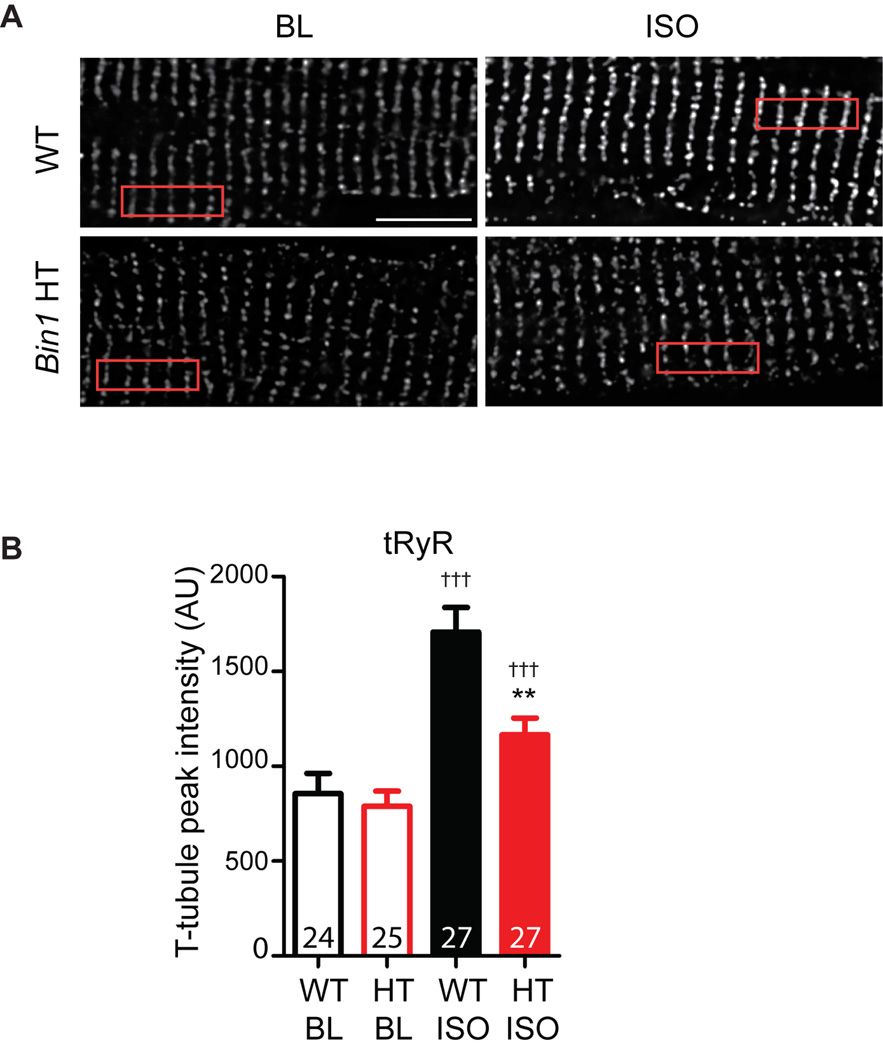

To further identify whether ISO-induced RyR phosphorylation results in recruitment of receptors from non-dyad membrane into BIN1-microdomains, we studied intracellular distribution of tRyR in both WT and Bin1 HT cardiomyocytes. In contrast to receptor phosphorylation level, tRyR protein expression remains unchanged after acute ISO treatment in both genotypes (Figure 1A). If no dynamic receptor movement occurs and ISO-increased P-RyR at t-tubules is solely contributed by phosphorylation of local de-phosphorylated receptors, intracellular distribution of tRyR should remain the same upon β-AR activation. However, consistent with more P-RyR at t-tubules (Figure 3), ISO also induces a significant increase in tRyR signal at t-tubules in WT cardiomyocytes, indicating rapid recruitment of more RyR protein into BIN1-microdomains upon β-AR activation (Figure 4A). Such an increase in tRyR at t-tubules becomes much less abundant in Bin1 HT cardiomyocytes (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Alteration in the intracellular distribution of tRyR upon β-AR stimulation. (A). Representative confocal images of tRyR (bottom) labeling in WT (left) and Bin1 HT (right) cardiomyocytes at baseline (ICI+CGP) and after 5 min treatment with 1 µmol/L ISO. Scale bar: 10 µm. (B). Average peak t-tubule intensity of tRyR from the boxed areas in (A) after ISO treatment in WT and Bin1 HT myocytes. ** indicates p<0.01 between genotypes; ††† indicates p<0.001 after ISO. Gene × treatment interaction term was identified as marginal significant (p=0.045) and remained in the final model.

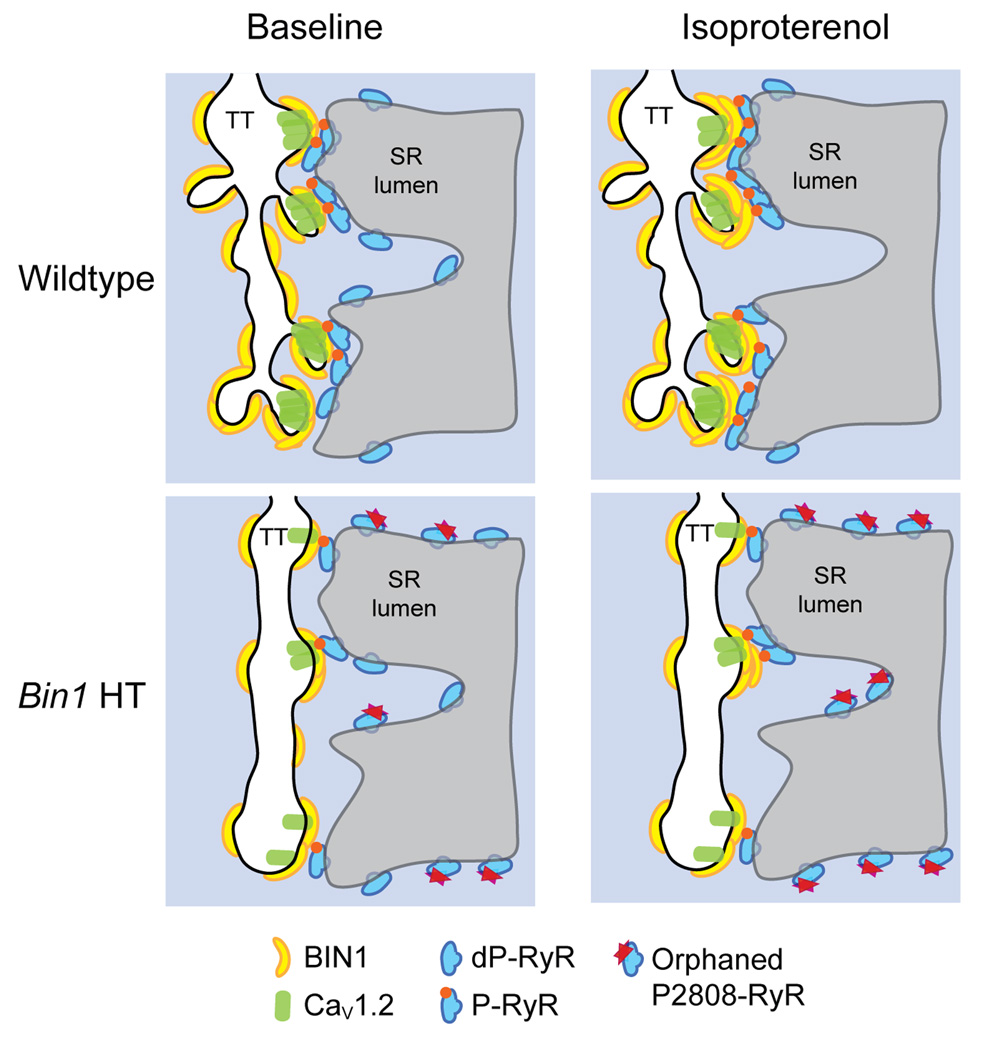

In summary, we identify that acute β-AR activation redistributes BIN1 to t-tubules, recruiting P2808-RyR from non-jSR membrane to BIN1-microdomains. When BIN1 is deficient, fewer BIN1-microdomains at t-tubules can be formed upon β-AR stimulation, resulting in the accumulation of uncoupled P-RyRs outside of dyads.

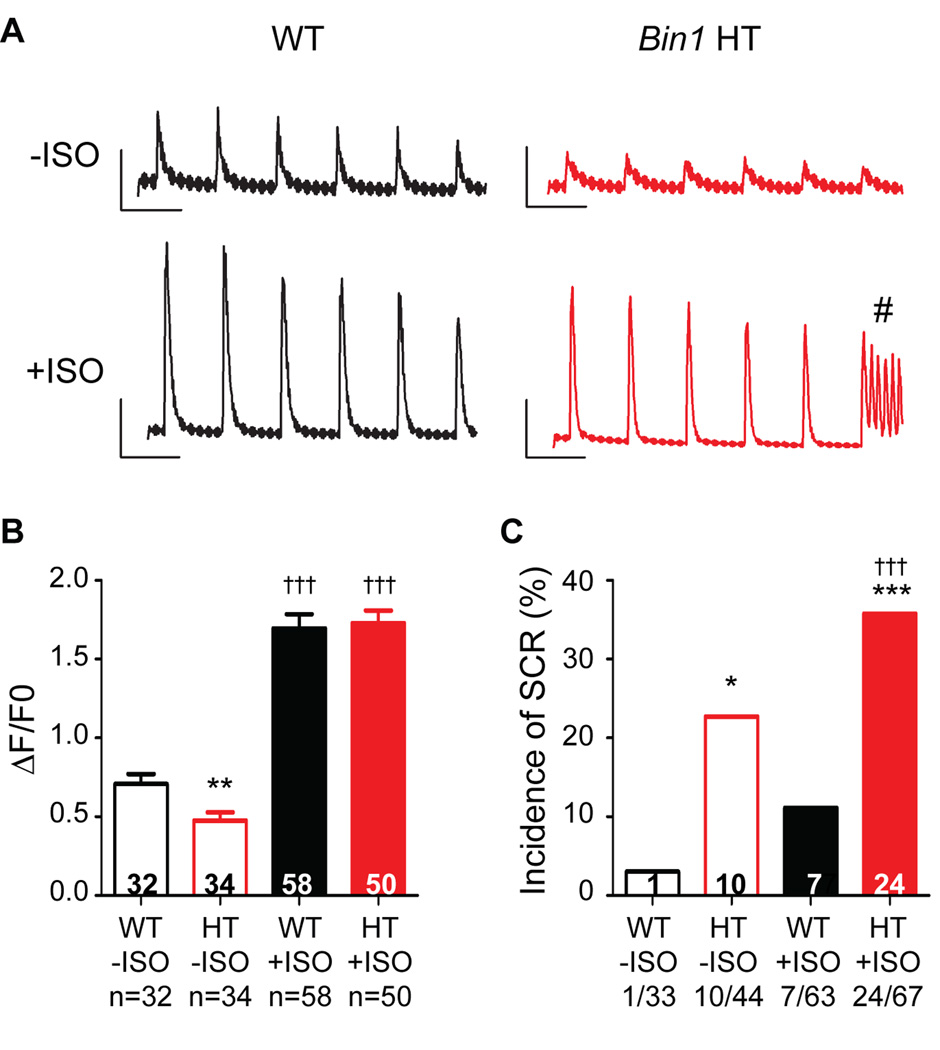

BIN1 deficiency leads to increased spontaneous calcium release

Calcium transients in response to ISO were examined in both WT and Bin1 HT cardiomyocytes. Bin1 HT cells have a significant reduction in calcium transient peak amplitude at baseline (Figure 5A–B), which is in part a result of impaired CaV1.2 channel trafficking to T-tubules17, 20. Reduced calcium transient can be rescued to WT levels after acute ISO treatment (Figure 5B), which also significantly increases incidence of SCR (Figure 5C). These data indicate that, in WT cardiomyocytes, β-AR stimulation concentrates BIN1-microdomains to recruit P-RyRs, increasing CICR gain while preserving electrical stability. In the case of Bin1 HT myocytes, impaired BIN1-microdomain fails to recruit all P-RyR into dyads, resulting in P-RyR accumulation elsewhere with a consequence of elevated orphaned leaky receptors (schematic in Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Isoproterenol (ISO) induced spontaneous calcium release (SCR) is increased in Bin1 HT cardiomyocytes. (A) Representative calcium transients from WT and Bin1 HT myocytes with field stimulation at 1 Hz in the presence and absence of ISO. # indicates SCR. (B) Peak amplitude of calcium transient in both WT and Bin1 HT cardiomyocytes with or without ISO. (C) The incidence of SCR is higher in Bin1 HT cells, particularly after ISO treatment. *, **, *** indicate p<0.05, p<0.01, or p<0.001 between genotypes; ††† indicates p<0.001 after ISO.

Figure 6.

Cartoon of the proposed model of BIN1 dependent recruitment of P2808-RyR to dyads during acute stress.

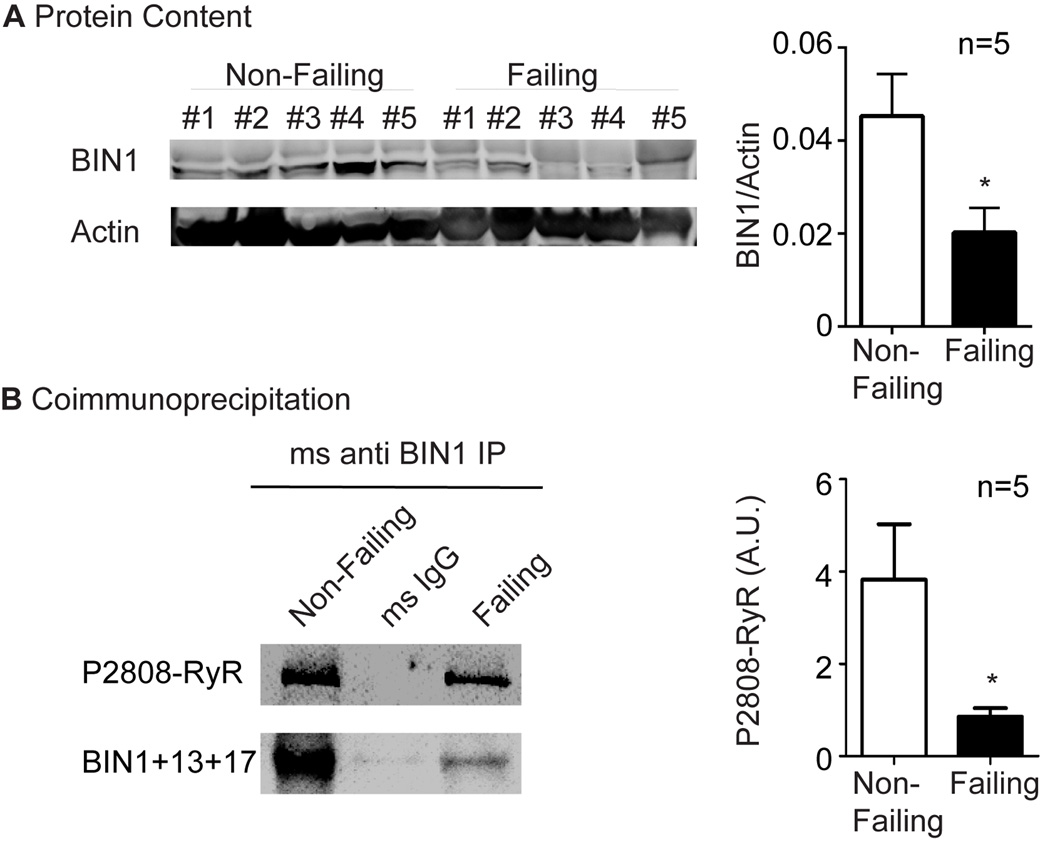

In human ischemic heart failure, BIN1 is reduced as is clustering with P2808-RyR

To explore whether BIN1-based regulation of P-RyR in mouse hearts is translatable to human disease, we examined the protein expression of cardiac BIN1 and its interaction with P-RyR in lysates from non-failing human hearts (acquired from patients who died from non-cardiac cause) as well as human hearts with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy (acquired on transplant). In the hearts with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy, there was a 50% reduction in BIN1 protein in human (Figure 7A), consistent with previous reports20. Furthermore, as indicated in Figure 7B, interaction between cardiac BIN1+13+17 and P-RyR was confirmed by positive coimmunoprecipitation. This experiment was repeated in all the non-failing and failing hearts and the quantitative data are included in the bar graph on the right side of Figure 7B, which indicates that coimmunoprecipitation of P2808-RyR is significantly diminished when BIN1 is reduced (n=5, p<0.05). Thus, in human hearts with ischemic cardiomyopathy, reduced BIN1+13+17 strongly correlates with a failure of P-RyR to organize at BIN1 induced T-tubule microdomains. The resultant accumulation of orphaned leaky P-RyR receptors outside of T-tubule dyads can contribute to heart failure progression, impairing contractility and promoting arrhythmias in patients with acquired heart failure.

Figure 7.

BIN1 is reduced in human acquired heart failure, resulting in decreased association with P2808-RyR. (A) Western blot of BIN1 in heart lysates from patients with either non-failing hearts or hearts with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy. (B) P2808-RyR co-immunoprecipitates with BIN1+13+17. IP: anti BIN1 exon 13; IB: rabbit anti P2808-RyR and BIN1-SH3. * indicates p<0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we find that ryanodine receptors can traffic in and out of dyads within a time scale of minutes. Fast movement of RyRs is regulated by BIN1-organized microdomains, which in turn are regulated by β-AR signaling. By organizing t-tubule microfolds18 to localize CaV1.217 with RyR channels (Figure 2), BIN1 serves as an important scaffold for dynamic microdomain regulation and calcium transient development.

Dynamic protein movement in and out of dyads

Dyads are the functional calcium releasing units underlying CICR. Up to 50% of t-tubule surface area is engaged in dyadic junction with jSR28. It is known that T-tubule remodeling5–7 occurs in diseased states such as heart failure, and with heart failure the dyad uncouples2, 29. At the jSR side of the dyad, RyRs form clusters ranging 10–300 RyR in size30, with relatively large distances of 0.6–1 µm between clusters31. Recent evidence also supports that the arrangement of RyRs in the dyad is neither uniform nor static32. Physiological conditions such as Mg2+ concentration and receptor phosphorylation can completely change the positioning of RyR tetramers within the dyad on a time scale of minutes32. The heterogeneity of the cluster size, large inter-cluster distance, dynamic arrangement of RyR tetramer as well as coupled gating33, all point to dynamic dyad regulation. Our data identify for the first time that RyRs can move into dyads after just 5 minutes of β-AR stimulation. Such a rapid receptor movement is mediated by enrichment of BIN1-organized microdomains at t-tubules. It remains unidentified how BIN1 rapidly accumulates at t-tubules to generate microdomains within 5 minutes of ISO stimulation. Interestingly, BIN1 is a membrane scaffolding protein with binding affinity to plasma membrane phospholipids34, which is known to be altered by acute β-AR stimulation in as short as 1–3 minutes35. The potential role of cardiac t-tubule membrane lipid species in BIN1-microdomain formation awaits future studies.

The dynamic feature of dyadic proteins is important for physiological stress response when P-RyRs are recruited to BIN1-microdomains for coupling with Cav1.2 channels, inducing synchronized release with increased CICR gain during stress. When BIN1 is transcriptionally reduced as in heart failure, impaired BIN1-microdomain prevents movement of P-RyR into dyads for efficient CICR (Figure 6).

Microdomain-based regulation of LTCC and RyR channels

We previously identified that BIN1 facilitates microtubule-dependent targeted delivery of LTCCs to t-tubules17. Together with the current discovery that BIN1 attracts hyper-active phosphorylated RyRs into the same microdomain, these data indicate that BIN1 serves as a protein bridge important to the maintenance of LTCC-RyR couplons at the dyads. Meanwhile, by creating diffusion resistant microfolds at t-tubule membrane18, BIN1 creates an electrically stable microenvironment with concentrated dyadic proteins for optimized EC coupling. The super-resolution 3D-STORM imaging and microdomain rendering (Figure 2) provide for the first time direct visualization into the spatial organization of BIN1-microdomains at the dyads, in which the membrane sculpting BIN1 creates “basket” like structures both holding LTCC clusters while protruding into RyR tetramers. In doing so, BIN1-microdomains are also likely to change the relative stoichiometry of LTCC channels to RyRs at the dyads, maximizing EC coupling gain.

Whether and how RyR function is regulated at BIN1-microdomains remain unclear, as well as the potential involvement of other membrane scaffolding proteins such as caveolin-3 and junctophilin-2. Caveoline-3 organizes caveolae microdomains distributed along sarcolemma and t-tubule membrane, which compartmentalizes LTCC channels with β-ARs36. Given that cellular distribution of caveoline-3 is altered in cardiomyocytes with BIN1 deficiency37, a potential interaction between caveolae and BIN1-microdomains may exist, facilitating coordinated channel regulation during acute stress. Junctophilin-2, on the other hand, is a t-tubule/jSR junctional protein which has been shown to maintain junctional membrane structure and interact with RyR, regulating EC coupling38. It is possible that BIN1 and junctophilin-2 may work together to ensure LTCC-RyR stoichiometry optimal for EC coupling. Whether the same or distinct populations of RyR receptors are involved in regulations by BIN1 and junctophilin-2 remains unclear. Future studies will be interesting to resolve how these microdomains are coordinated to control dyad function in normal and stressed hearts.

Regulation of RyR macromolecular complex

Ryanodine receptors exist as homotetromers. Each monomer consists of a C-terminal transmembrane pore domain and a very large cytoplasmic domain containing various modulatory binding sites39, 40. Calsequestrin, triadin, and junctin are known regulators of RyR via luminal calcium41. The large cytoplasmic domain of RyR serves as the platform for binding of various modulators including calstabin42, PKA and mAKAP (muscle A kinase anchoring protein), phosphatases PP1 and PP2A10, 11, as well as calmodulin43 and CaMKII25, constituting a macromolecular signaling complex for efficient temporal and spatial regulation of RyR function. These modulators alter the biophysical properties of RyR either through regulation of receptor phosphorylation / dephosphorylation, or via stabilization of the closed state of RyR as in the case of calstabin.

Our study suggests BIN1 as an additional, membrane deformation, component of the macromolecular complex. It remains uncertain whether BIN1 binds to the large cytosolic domain of RyR directly or indirectly through other molecules in the complex. The atomic resolution of RyR structure solved recently40 can provide much insight into how BIN1 interacts within RyR macromolecular complex39. Furthermore, the interaction between BIN1 and RyR is increased after receptor phosphorylation (Figure 2), similar to the known binding preference of BIN1 to negatively charged phospholipids. The enrichment of positively charged residues within the BAR domain of BIN1 may explain its preferential binding to negatively charged lipids and proteins, with quick response to β-AR signaling.

Distribution of phosphorylated RyR – implication in human heart failure

The biophysical properties of RyR can be altered through phosphorylation at different residues, which when hyper-phosphorylated contributes to heart failure progression. Phosphorylation of RyRs at the primary PKA site Ser2808 increases open probability and calcium sensitivity10, 14, and is essential for β-AR-mediated regulation13, 14. Phosphorylation at a nearby Ser2814 by CaMKII25 is essential for positive force frequency relationship44, and is considered to mediate sustained contractile response45 when β-AR is chronically stimulated46. In the current study, using P2808-RyR which is consistently hyper-phosphorylated upon 5 min of β-AR activation, we focused on the acute movement of phosphorylated receptors to BIN1-microdomains. Given the preferential binding of BIN1 to negatively charged receptors, it is likely that BIN1 also attracts P2814-RyR when CaMKII is activated with chronic β-AR stimulation.

Although extensively studied with regard to the role of RyR hyper-phosphorylation in heart failure pathophysiology15, 47, results from the current study introduce a new perspective that subcellular localization of phosphorylated RyRs may also matter. When BIN1 is reduced with fewer phosphorylated RyRs associated (Figure 7), as occurs in human acquired heart failure, P-RyR localization into dyads will be impaired, limiting efficient CICR. Outside of the dyads, accumulation of uncoupled receptors not only fails to improve CICR gain, but also forms leaky receptor clusters contributing to spontaneous calcium release and arrhythmias (Figure 5). Reduced BIN1 with altered RyR distribution therefore likely contributes to the pathophysiology of heart failure progression.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the membrane deformation protein BIN1 organizes t-tubule microdomains to support interaction between dyadic proteins. These BIN1 - microdomains are dynamic, reorganizing in response to acute stress, altering myocardial function. Reduced BIN1 with impaired microdomain-formation also likely contributes to EC uncoupling and electrical instability in failing hearts. The current study is limited to the acute stress response in isolated mouse hearts and cardiomyocytes without systemic sympathetic innervation. The results provide important understandings of the dynamic nature of the dyadic proteins, while with limited assessment of chronic pathological changes during heart failure progression. The human data (Figure 7) suggest that our findings may be applicable to patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy, but future studies in well controlled in vivo mouse models of ischemic heart failure are necessary to better elucidate the biology of chronic BIN1-microdomain regulation of dyad function and EC coupling.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspectives.

Heart failure is the fastest growing cardiovascular disorder affecting over six million Americans, with 600,000 new cases per year and 50,000–100,000 who are in end-stage disease refractory to medical therapy. Acquired heart failure, usually due to ischemic cardiomyopathy, is the most common form of heart failure in the United States. For ischemic cardiomyopathy, just as with other acquired dilated cardiomyopathy, it is well understood that impaired sarcomeric dyad function leads to diminished calcium transients which decreases contractility, contributing to the heart failure progression. The dyad is coupling between t-tubule L-type calcium channels (LTCC) with nearby sarcoplasmic membrane ryanodine receptors (RyR2). The mechanisms by which dyad function is negatively affected in heart failure remain incompletely understood. Here we report that dynamic movement of RyR2 into dyads for LTCC-RyR2 complex formation is under the control of membrane microdomains organized by a particular cytoskeleton and membrane scaffolding protein bridging integrator 1 (BIN1), which helps to maintain excitation-contraction coupling during adrenergic stress. In acquired human heart failure, BIN1 is reduced and orphaned phosphorylated RyR2s accumulate outside of dyads, lessening contractility and increasing arrhythmogenesis. The results suggest that interventions which preserve BIN1 organized t-tubule microdomains could be of therapeutic benefit to improve cardiac function and lessen arrhythmia in millions of patients with failing hearts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robin M. Shaw for helpful advice and providing access to de-identified heart lysates from human samples stored within the CSHI Biobank, Tara Hitzeman for technical support, and Sarcotein Diagnostics for the recombinant anti-BIN1 exon 13 antibody.

Funding Sources: Dr. Fu is supported by American Heart Association (12SDG12080084) and Dr. Hong is supported by National Institute of Heart / National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI, R00-HL109075).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez AM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Lederer MR, Santana LF, Cannell MB, McCune SA, Altschuld RA, Lederer WJ. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 1997;276:800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perreault CL, Shannon RP, Komamura K, Vatner SF, Morgan JP. Abnormalities in intracellular calcium regulation and contractile function in myocardium from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:932–938. doi: 10.1172/JCI115674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez AM, Guatimosim S, Dilly KW, Vassort G, Lederer WJ. Heart failure after myocardial infarction: altered excitation-contraction coupling. Circulation. 2001;104:688–693. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.092285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He J, Conklin MW, Foell JD, Wolff MR, Haworth RA, Coronado R, Kamp TJ. Reduction in density of transverse tubules and L-type Ca(2+) channels in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldwell JL, Smith CE, Taylor RF, Kitmitto A, Eisner DA, Dibb KM, Trafford AW. Dependence of cardiac transverse tubules on the BAR domain protein amphiphysin II (BIN-1) Circ Res. 2014;115:986–996. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Phosphorylation sites required for regulation of cardiac calcium channels in the fight-or-flight response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:19621–19626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319421110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Basal and beta-adrenergic regulation of the cardiac calcium channel CaV1.2 requires phosphorylation of serine 1700. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16598–16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419129111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, Yang YM, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of ryanodine receptors: a novel role for leucine/isoleucine zippers. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:699–708. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiken S, Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, He KlKL, Prieto A, Becker E, Yi GhGH, Wang J, Burkhoff D, Marks AR. beta-adrenergic receptor blockers restore cardiac calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) structure and function in heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2843–2848. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Kushnir A, Reiken S, Meli AC, Wronska A, Dura M, Chen BX, Marks AR. Role of chronic ryanodine receptor phosphorylation in heart failure and beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4375–4387. doi: 10.1172/JCI37649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken S, Vest JA, Wronska A, Marks AR. Ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel PKA phosphorylation: a critical mediator of heart failure progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:511–518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510113103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx SO, Marks AR. Dysfunctional ryanodine receptors in the heart: new insights into complex cardiovascular diseases. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;58:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ather S, Respress JL, Li N, Wehrens XH. Alterations in ryanodine receptors and related proteins in heart failure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:2425–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong TT, Smyth JW, Gao D, Chu KY, Vogan JM, Fong TS, Jensen BC, Colecraft HM, Shaw RM. BIN1 localizes the L-type calcium channel to cardiac T-tubules. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong T, Yang H, Zhang SS, Cho HC, Kalashnikova M, Sun B, Zhang H, Bhargava A, Grabe M, Olgin J, Gorelik J, Marban E, Jan LY, Shaw RM. Cardiac BIN1 folds T-tubule membrane, controlling ion flux and limiting arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2014;20:624–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.3543. Epub 2014 May 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyon AR, Nikolaev VO, Miragoli M, Sikkel MB, Paur H, Benard L, Hulot JS, Kohlbrenner E, Hajjar RJ, Peters NS, Korchev YE, Macleod KT, Harding SE, Gorelik J. Plasticity of surface structures and beta(2)-adrenergic receptor localization in failing ventricular cardiomyocytes during recovery from heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:357–365. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong TT, Smyth JW, Chu KY, Vogan JM, Fong TS, Jensen BC, Fang K, Halushka MK, Russell SD, Colecraft H, Hoopes CW, Ocorr K, Chi NC, Shaw RM. BIN1 is reduced and Cav1.2 trafficking is impaired in human failing cardiomyocytes. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:812–820. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang MY, Boulden J, Sutanto-Ward E, Duhadaway JB, Soler AP, Muller AJ, Prendergast GC. Bin1 ablation in mammary gland delays tissue remodeling and drives cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:100–107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA, Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang B, Wang W, Bates M, Zhuang X. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. Science. 2008;319:810–813. doi: 10.1126/science.1153529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimm M, Ling H, Brown JH. Crossing signals: relationships between beta-adrenergic stimulation and CaMKII activation. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1296–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken SR, Marks AR. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res. 2004;94:e61–e70. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125626.33738.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez P, Bhogal MS, Colyer J. Stoichiometric phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptor on serine 2809 by calmodulin-dependent kinase II and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38593–38600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C301180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tokunaga M, Imamoto N, Sakata-Sogawa K. Highly inclined thin illumination enables clear single-molecule imaging in cells. Nat Methods. 2008;5:159–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page E, Surdyk-Droske M. Distribution, surface density, and membrane area of diadic junctional contacts between plasma membrane and terminal cisterns in mammalian ventricle. Circ Res. 1979;45:260–267. doi: 10.1161/01.res.45.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bito V, Heinzel FR, Biesmans L, Antoons G, Sipido KR. Crosstalk between L-type Ca2+ channels and the sarcoplasmic reticulum: alterations during cardiac remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:315–324. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Comparative ultrastructure of Ca2+ release units in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;853:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soeller C, Crossman D, Gilbert R, Cannell MB. Analysis of ryanodine receptor clusters in rat and human cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14958–14963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703016104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asghari P, Scriven DR, Sanatani S, Gandhi SK, Campbell AI, Moore ED. Nonuniform and variable arrangements of ryanodine receptors within mammalian ventricular couplons. Circ Res. 2014;115:252–262. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marx SO, Gaburjakova J, Gaburjakova M, Henrikson C, Ondrias K, Marks AR. Coupled gating between cardiac calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors) Circ Res. 2001;88:1151–1158. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee E, Marcucci M, Daniell L, Pypaert M, Weisz OA, Ochoa GC, Farsad K, Wenk MR, De Camilli P. Amphiphysin 2 (Bin1) and T-tubule biogenesis in muscle. Science. 2002;297:1193–1196. doi: 10.1126/science.1071362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edes I, Solaro RJ, Kranias EG. Changes in phosphoinositide turnover in isolated guinea pig hearts stimulated with isoproterenol. Circ Res. 1989;65:989–996. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balijepalli RC, Foell JD, Hall DD, Hell JW, Kamp TJ. Localization of cardiac L-type Ca(2+) channels to a caveolar macromolecular signaling complex is required for beta(2)-adrenergic regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7500–7505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503465103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laury-Kleintop LD, Mulgrew JR, Heletz I, Nedelcoviciu RA, Chang MY, Harris DM, Koch WJ, Schneider MD, Muller AJ, Prendergast GC. Cardiac-Specific Disruption of Bin1 in Mice Enables a Model of Stress- and Age-Associated Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Cell Biol. 2015;116:2541–2551. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beavers DL, Landstrom AP, Chiang DY, Wehrens XH. Emerging roles of junctophilin-2 in the heart and implications for cardiac diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:198–205. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santulli G, Marks AR. Essential Roles of Intracellular Calcium Release Channels in Muscle, Brain, Metabolism, and Aging. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2015;8:206–222. doi: 10.2174/1874467208666150507105105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zalk R, Clarke OB, des Georges A, Grassucci RA, Reiken S, Mancia F, Hendrickson WA, Frank J, Marks AR. Structure of a mammalian ryanodine receptor. Nature. 2015;517:44–49. doi: 10.1038/nature13950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gyorke I, Hester N, Jones LR, Gyorke S. The role of calsequestrin, triadin, and junctin in conferring cardiac ryanodine receptor responsiveness to luminal calcium. Biophys J. 2004;86:2121–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74271-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Timerman AP, Jayaraman T, Wiederrecht G, Onoue H, Marks AR, Fleischer S. The ryanodine receptor from canine heart sarcoplasmic reticulum is associated with a novel FK-506 binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198:701–706. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamaguchi N, Xu L, Pasek DA, Evans KE and Meissner G. Molecular basis of calmodulin binding to cardiac muscle Ca(2+) release channel (ryanodine receptor) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23480–23486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kushnir A, Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Reiken S, Marks AR. Role of CaMKIIdelta phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in the force frequency relationship and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10274–10279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang W, Zhu W, Wang S, Yang D, Crow MT, Xiao RP, Cheng H. Sustained beta1-adrenergic stimulation modulates cardiac contractility by Ca2+/calmodulin kinase signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2004;95:798–806. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145361.50017.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimm M, Ling H, Willeford A, Pereira L, Gray CB, Erickson JR, Sarma S, Respress JL, Wehrens XH, Bers DM, Brown JH. CaMKIIdelta mediates beta-adrenergic effects on RyR2 phosphorylation and SR Ca(2+) leak and the pathophysiological response to chronic beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;85:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Houser SR. Role of RyR2 phosphorylation in heart failure and arrhythmias: protein kinase A-mediated hyperphosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor at serine 2808 does not alter cardiac contractility or cause heart failure and arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2014;114:1320–1327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300569. discussion 1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.