Abstract

Background

Preferred or dominant limb is often subjectively defined by self-report. The purpose was to objectively classify preferred landing leg during landing in athletes previously injured and uninjured.

Methods

Subjects with history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (n=101) and uninjured controls (n=57) participated. Three trials of a drop vertical jump were collected. Leg dominance was defined as the leg used to kick a ball while landing leg preference was calculated as the leg which landed first during landing trials. Limb symmetry index was also calculated during a single leg hop battery. The distribution of subjects that landed first on their uninvolved or dominant leg, respectively, was statistically compared. Limb symmetry from the single leg hop tests were compared within each subgroup.

Findings

The distribution of preferred landing leg to uninvolved limb for injured (71%) and dominant limb for controls (63%) was not statistically different between groups (p=0.29). Limb symmetry was decreased in injured subjects that preferred to land on their uninvolved limb compared to their involved limb during single leg (p<0.001), triple (p<0.001), cross-over (p<0.001), and timed hops (p=0.007). Differences in limb symmetry were not statistically different in controls (p>0.05).

Interpretation

The leg that first contacts the ground during landing may be a useful strategy to classify preferred landing leg. 29% of injured subjects preferred to land on their involved leg which may relate to improved confidence and readiness to return to sport as improved limb symmetry were present during hop tests.

Keywords: Preferred landing leg, dominant limb, landing biomechanics, limb asymmetries, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, drop vertical jump

1. INTRODUCTION

Identification of dominant limb with athletic activity is often subjectively defined by self-report. For example, several research groups determine leg dominance by asking the subject which leg they would prefer to use to kick a ball as far as possible.1-5 However, the operational definition of ‘dominant’ may vary within this question as either the stance leg or the kicking leg.1,6 Another approach may involve individually matching an injured side to a specific control’s same side.5 However, in larger prospective studies with multiple investigative groups involved in injury surveillance, group allocation may change and result in unbalanced cohorts. Therefore, it is often difficult to match injured and uninjured cohorts across multiple sports when examining side-to-side asymmetries.

Lower extremity biomechanics have been examined on the preferred landing leg during a variety of tasks.7 Direct comparisons with a preferred leg (leg chosen to land on the majority of the trials) may be used to determine side-to-side asymmetries. Asymmetries in injured athletes are typically observed early in the rehabilitation process and may persist following return to sport. For example, in young, active individuals following primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (ACLR), greater quadriceps femoris muscle strength side-to-side asymmetries at the time of return to sport are associated with worse performance on measures of function and performance, and asymmetrical landing strategies during a bilateral landing task.8,9 Importantly, side-to-side asymmetries during landing may relate to increased risk of re-injury after primary, unilateral ACLR.10 A common task used to identify altered biomechanics involves a bilateral drop vertical jump (DVJ) maneuver.11 Subjects are instructed to drop off a box simultaneously with both limbs, land bipedally and immediately perform a maximum vertical jump. Subtle side-to-side timing differences in landing have been previously utilized to identify a preferred landing side in uninjured and injured athletes.12 Specifically, patients following unilateral ACLR tend to lead with their uninvolved limb, which may offer a unique methodology to identify and match a control subject’s preferred limb.12 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to objectively classify the preferred landing leg during a bipedal landing task in athletes previously injured and uninjured. We hypothesized that a similar distribution would be observed among an injured cohort landing first on their uninvolved limb compared to the preferred leg in an uninjured cohort. Furthermore, a secondary purpose was to determine if limb asymmetries, during single leg hops would be observed within ACLR and control groups based on group allocation.

2. METHODS

2.1 Subjects

One hundred fifty-eight subjects were included in this study from an ongoing prospective study that has been previously described.10 Subjects following unilateral ACLR and return to sport (ACLR n=101, female=63.4%) and uninjured control subjects (CTRL n=57, female=73.7) participated. Subject demographics (Table 1) were not statistically different between groups. ACLR subjects did not follow a standardized rehabilitation and was not controlled in this study. Informed written consent was obtained from each subject/parent in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board. Dominant leg was defined in the current study as the leg the subject would use to kick a ball as far as possible. The uninvolved leg was defined in the ACLR group as side that was not surgically repaired.

TABLE 1.

Subject Demographics

| ACLR (n=101) | CTRL (n=57) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 167.3 (11.2) | 166.5 (8.8) | 0.7 |

| Mass (kg) | 65.6 (15.1) | 61.4 (11.9) | 0.1 |

| Age (yrs) | 16.7 (3.0) | 17.2 (2.5) | 0.4 |

|

Post Surgery

(months) |

8.3 (2.5) | - | - |

Mean (SD) demographics for ACLR and CTRL groups.

2.2 Procedures

Subjects performed three DVJ trials (Figure 1) from a 31cm box and landed on two force platforms (1200Hz, AMTI, Watertown, MA). Each subject dropped down from the box with the standardized instructions to leave the box with both feet at the same time, immediately when hitting the ground, jump up as high as possible towards a suspended target positioned overhead. Subjects also completed a single leg hop battery.13 Four single-leg hop tests were performed, including three hop tests for distance, single hop, triple hop, and triple crossover hop; and a 6-meter timed hop. For each test, a practice trial and two measurement trials were performed on each limb, tested in a random order. The averages of two measurement trials for each limb were used to calculate limb symmetry index (involved or non-dominant score divided by uninvolved or dominant score *100% for the distance measures and uninvolved or dominant time divided by the involved or non-dominant time *100% for the timed hop). A limb symmetry index of less than 100 indicates deficits in the involved or non-dominant limb.

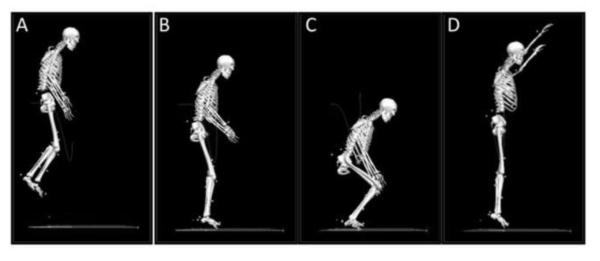

Figure 1.

Example of drop vertical jump (DVJ). A) Leave 31cm box with both feet at the same time. B) Initial contact was calculated for each limb. C) Subject was instructed to perform a maximum vertical jump as soon as they hit the ground. D) Toe off prior to maximum vertical jump.

2.3 Data Analysis

Initial ground contact for both limbs during the DVJ was calculated (Matlab, MathWorks, Natick, MA) as the time that the unfiltered vertical ground reaction force first exceeded 10N. The side that made initial contact first, during the majority of the trials, was operationally defined as the preferred leg. When timing was equal (exact same frame number identified when vertical ground reaction force first exceeded 10N), the side that had the larger magnitude of vertical ground reaction force at initial contact was defined as preferred. The absolute time difference between the initial contact for each leg was calculated and compared between ACLR and CTRL groups.

The distribution of ACLR and CTRL that landed first on their uninvolved or dominant, respectively, was statistically compared with chi-square analysis. One-way ANOVA (p<0.05) was used to determine if differences existed in initial contact timing between ACLR and CTRL. Within the ACLR group, subjects were dichotomized into those that preferred to land on their uninvolved limb first compared to those that preferred to land on their involved limb first. Likewise, CTRL subjects were dichotomized into groups based on their preference to land first on dominant leg compared to non-dominant leg. Limb symmetry indices from the single leg hop tests were statistically compared within the ACLR and CTRL subgroups (ANOVA p<0.05).

3. RESULTS

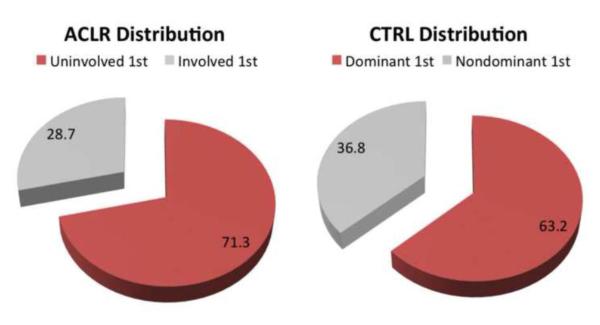

Absolute initial contact timing differences between landing sides were not statistically different between groups (p=0.19). Specifically, ACLR had a difference of 7.4 (SD 5.1) milliseconds compared to 6.3 (SD 4.9) milliseconds in the CTRL group. 71.3% of ACLR subjects preferred to land with initial contact on their uninvolved limb during a DVJ task (Figure 2). In comparison, 63.2% of CTRL subjects preferred to land on their dominant limb first. The distribution of preferred landing leg to uninvolved limb for ACLR and dominant limb for CTRL was not statistically different between groups (p=0.29).

Figure 2.

Distribution of ACLR group and CTRL group that landed first on their uninvolved compared to involved limb and dominant compared to nondominant limb, respectively.

Within the ACLR cohort, limb symmetry indices during all four single leg hop tests were significantly different between ACLR subjects that preferred to initially land on their uninvolved limb compared to their involved limb during the DVJ trials. Specifically, limb symmetry was decreased in ACLR subjects that preferred to land on their uninvolved limb (UN, n=72) compared to their involved limb (IN, n=29), respectively, during the single leg hop (IN: 102.5 (7.4), UN: 93.7 (6.5), p<0.001), triple hop (IN: 101.7 (6.3), UN: 94.1 (6.8), p<0.001), cross-over hop (IN: 102.5 (10.6), UN: 94.0 (6.6), p<0.001), and timed hop (IN: 100.6 (10.2), UN: 95.6 (7.3), p=0.007) tests. The time post surgery was not different between the ACLR groups that preferred to land with initial contact on their uninvolved limb (8.3 months) compared to involved limb (8.2 months, p=0.87). 52.5% of the ACLR subjects injured their previously determined dominant limb (based on which side they would use to kick a ball). The distribution of dominant compared to non-dominant injured side was not statistically different (p=0.66) between the ACLR groups that preferred to land with initial contact on their uninvolved limb compared to involved limb. Additionally, there were no differences (p=whether the injured side was classified as dominant compared to nondominant based on which leg they would kick a ball with

In the CTRL group, limb symmetry indices on the single leg hop tests were not statistically different between those that preferred to land on their dominant (D, n=36) versus non-dominant (ND, n=21) limb, respectively (single leg hop, D: 98.9 (5.6), ND: 100.5 (4.6), p=0.27; triple hop, D: 98.1 (5.0), ND: 100.3 ± 4.2, p=0.09; cross-over hop, D: 99.7 (4.9), ND: 99.0 (6.8), p=0.66; timed hop, D: 98.4 (6.3), ND: 99.1 (5.6), p=0.73).

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to objectively classify the preferred landing leg during a DVJ in athletes with and without an ACLR at the time of return to sport. The majority of uninjured athletes landed first on their dominant limb approximately 6 milliseconds before their non-dominant limb. Similarly, a majority of subjects in the ACLR group landed approximately 7 milliseconds earlier on their uninvolved limb compared to the involved limb. The subtle timing differences between ACLR and CTRL were not statistically different. The results indicate that matching injured and uninjured cohorts can be accomplished by examining subtle landing differences between sides. Specifically, this approach may benefit larger prospective studies with multiple investigative groups and unbalanced cohorts. Bilateral landing tasks, compared to unilateral landings, offer a unique paradigm in patients following an injury, as a loading preference may exist. For instance, side-to-side differences exist during bilateral drop vertical jump and stop jump in subjects following ACLR.12,14,15

The current findings indicate that a small proportion of ACLR subjects that preferred to land initially on their involved limb had improved single leg hop symmetry indices compared to ACLR subjects that landed first on their uninvolved limb. This likely indicates greater confidence in the surgically repaired side. The single leg hop battery symmetry values in ACLR were comparable to previous literature.16 Additionally, the use of preferred landing leg may be a useful screening component during return to sport testing. The screening component should be further developed and may be beneficial as relatively inexpensive timing mats could be used with a double leg task that my be advantageous over single leg maximal effort hops.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The leg that first contacts the ground during the majority of landings may be a useful strategy to classify leg preference. Interestingly, approximately 29% of ACLR, at time of return to sport, preferred to land on their involved leg compared to their uninvolved leg. This finding may relate to improved confidence and readiness to return to sport as improved limb symmetry indices were also present during the four hop tests. The allocation of leg dominance, obtained via questionnaire, may not relate to landing leg preference as approximately 37% of uninjured athletes preferred to land initially on their non-dominant leg. Furthermore, this indicates that matching injured and uninjured cohorts based on preferred landing leg may be an appropriate methodology when examining side-to-side asymmetries.

Highlights.

71% of subjects with history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction preferred to land on their uninvolved leg.

29% of subject with history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction that landed first on involved leg had improved limb symmetry during hop tests battery.

Absolute initial contact timing differences between landing sides were not statistically different between subjects with history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and uninjured control subjects.

Methodology used in this brief report may be appropriate to identify landing leg preference in future studies with injured and uninjured cohorts.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by support from the National Institutes of Health grant F32-AR055844 and the National Football League Charities Medical Research Grants 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest for each author of this study

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Valgus knee motion during landing in high school female and male basketball players. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003;35(10):1745–1750. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000089346.85744.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison EL, Duenkel N, Dunlop R, Russell G. Evaluation of single-leg standing following anterior cruciate ligament surgery and rehabilitation. Phys. Ther. 1994;74(3):245–252. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shultz SJ, Perrin DH, Adams MJ, Arnold BL, Gansneder BM, Granata KP. Neuromuscular Response Characteristics in Men and Women After Knee Perturbation in a Single-Leg, Weight-Bearing Stance. J. Athl. Train. 2001;36(1):37–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lephart SM, Ferris CM, Riemann BL, Myers JB, Fu FH. Gender differences in strength and lower extremity kinematics during landing. Clin. Orthop. 2002;(401):162–169. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ireland ML, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT, Davis IM. Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2003;33(11):671–676. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2003.33.11.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colby SM, Hintermeister RA, Torry MR, Steadman JR. Lower limb stability with ACL impairment. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1999;29(8):444–451. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.8.444. discussion 452-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard JS, Fazio MA, Mattacola CG, Uhl TL, Jacobs CA. Structure, sex, and strength and knee and hip kinematics during landing. J. Athl. Train. 2011;46(4):376–385. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.4.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt LC, Paterno MV, Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Strength Asymmetry and Landing Mechanics at Return to Sport after ACL Reconstruction. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmitt LC, Paterno MV, Hewett TE. The impact of quadriceps femoris strength asymmetry on functional performance at return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012;42(9):750–759. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical Measures of Neuromuscular Control and Valgus Loading of the Knee Predict Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Athletes: A Prospective Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2005;33(4):492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Effects of sex on compensatory landing strategies upon return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2011;41(8):553–559. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mangine RE. Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am. J. Sports Med. 1991;19(5):513–518. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler RJ, Dai B, Garrett WE, Queen RM. Changes in landing mechanics in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction when wearing an extension constraint knee brace. Sports Health. 2014;6(3):203–209. doi: 10.1177/1941738114524910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterno MV, Ford KR, Myer GD, Heyl R, Hewett TE. Limb asymmetries in landing and jumping 2 years following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2007;17(4):258–262. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31804c77ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams GN, Snyder-Mackler L, Barrance PJ, Axe MJ, Buchanan TS. Neuromuscular function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autologous semitendinosus-gracilis graft. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2005;15(2):170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]