Abstract

Introduction

Questions remain regarding nodal evaluation and upstaging between thoracotomy (open) and Video Assisted Thoracic Surgery (VATS) approaches to lobectomy for early stage lung cancer. Potential differences in nodal staging based on operative approach remains as the final significant barrier to widespread adoption of VATS lobectomy. The current study examines differences in nodal staging between open and VATS lobectomy.

Methods

The National Cancer Data Base was queried for lung cancer patients with clinical stage ≤T2N0M0 who underwent lobectomy in 2010-2011. Propensity score matching was performed to compare rate of nodal upstaging in VATS vs. open approaches. Additional sub-group analysis was performed to assess whether or not rates of upstaging differed by specific clinical settings.

Results

A total of 16,983lobectomies were analyzed; 4935 (29.1%) were performed via VATS. Nodal upstaging was more frequent in the open group (12.8 vs. 10.3%; p<0.001). In 4,437 matched pairs, nodal upstaging remained more common for open approaches. For a sub-group of patients whose number of lymph nodes examined was ≥7, propensity matching revealed that nodal upstaging remained more common following open vs. VATS (14.0 vs. 12.1%; p=0.03). However, for patients who were treated in an Academic/Research Facility, the difference in nodal upstaging was no longer significant between an open vs. VATS approach (12.2 vs. 10.5%, p=0.08).

Conclusions

Nodal upstaging was more frequently observed with thoracotomy compared to VATS for early stage lung cancer. However, nodal upstaging appears to be impacted by facility type, which may represent a surrogate for minimally invasive expertise.

Keywords: Lung cancer surgery, Lobectomy, Staging

Introduction

The surgical approach for lung cancer treatment has traditionally been via a thoracotomy. However, due to the increased morbidity of open chest surgery, especially in lung cancer patients who often have multiple medical comorbidities, minimally invasive options are frequently utilized. Over the past two decades, video assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) has been increasingly used as a minimally invasive approach for lung cancer surgery, with excellent morbidity and mortality rates.1-4 Short-term advantages of VATS over thoracotomy are well documented: fewer complications, less pain, improved lung function, shorter recovery period and lower acute care costs.3,5-12 VATS is particularly beneficial in the elderly (>70 years), with fewer complications and shorter hospital stay compared to thoracotomy.5

The long-term efficacy of VATS versus thoracotomy (open) approaches for lung cancer surgery is uncertain. Survival following surgery for node-negative lung cancer is associated with the number of lymph nodes (LN) evaluated.13,14 Higher numbers of lymph nodes resected provide more complete staging and reduce the likelihood of missing metastatic lymph nodes. Research has demonstrated that variability exists in lymph node assessment with VATS compared to thoracotomy.15 A critical study from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) General Thoracic Surgery Database (GTSD) found that an open approach identified a greater number of occult lymph node metastases compared to VATS.16 Two recent studies also demonstrated superior lymph node staging with thoracotomy compared to VATS.17,18 Incomplete lymph node evaluation with VATS could compromise survival by leaving residual cancer and limiting staging data, thus impacting optimal treatment based on accurate staging.

In light of the potential differences in completeness of nodal staging and safety of VATS compared to thoracotomy, a critical gap exists regarding the optimal surgical approach (open vs. VATS) for early stage lung cancer treatment with respect to long-term survival. The current study was designed to examine differences in nodal staging between open and VATS lobectomy in a large, national, generalizable dataset.

Methods

Data Collection and Definition of Study Variables

The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB), an oncology outcomes database maintained by the American Cancer Society and the American College of Surgeons, represents approximately 70% of newly diagnosed cancer cases within the United States and is comprised of over 30 million historical records collected from more than 1500 Commission on Cancer –accredited facilities. The NCDB Participant Use File 2011 was queried for non-small cell lung cancer patients with clinical stage ≤T2N0M0 who underwent lobectomy in 2010-2011.

All lung cancers were staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th Edition of Lung Cancer Staging guidelines.19,20 Surgical approach (VATS vs. open) was defined on an intention-to-treat basis, thus thoracoscopic cases converted to open were classified as VATS. The facility type was determined by Commission on Cancer program accreditation level and was based on types of services provided and case volume.21 Community cancer programs treat 100-500 cancer cases per year, comprehensive community cancer programs treat > 500 cancer cases, and academic or research programs (including National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers) treat > 500 cancer cases, in addition to providing postgraduate medical education.

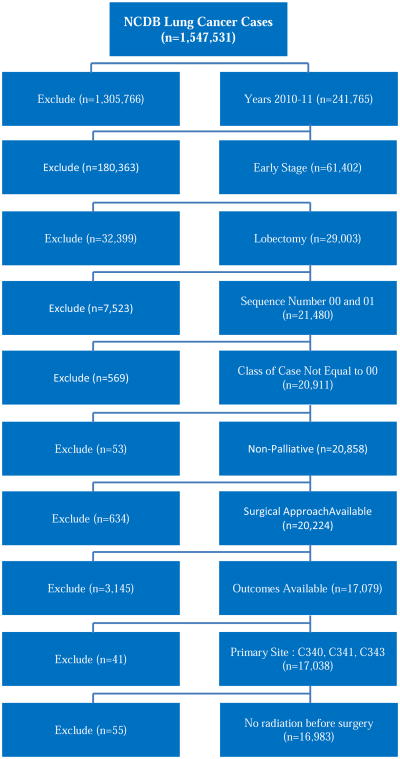

Primary outcome variables of interest included thirty-day mortality, number of regional lymph nodes (LN) examined, regional LN positivity, AJCC pathologic nodal status (N stage), readmission within 30 days of surgical discharge, status of surgical margins, and length of surgical inpatient stay. Long-term survival data after 2006 is not available in the NCDB PUF 2011, and thus not available to be included within our analysis. Cases with unknown surgical approach, concomitant cancer diagnoses, palliative care, preoperative radiation, or missing primary outcome variables were excluded from the data set. After all inclusion and exclusion criteria were met, 16,983 cases remained available for analysis (Figure 1). Approval for the study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board of Emory University.

Figure 1. Summary of patient selection using exclusion criteria.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

All data are presented as mean values with standard deviations or as counts with percentages. All data are complete except where noted within the text or footnotes of tables. Descriptive statistics for each variable were reported. All statistical tests were two-sided, with the alpha threshold of significance set at 0.05. The univariate association of each covariate with surgical approach and the categorical outcomes was assessed using the chi-square test for categorical covariates and ANOVA for numerical covariates. The univariate association of each covariate with inpatient stay was assessed using ANOVA for categorical covariates and Pearson correlation for numerical covariates.

To reduce the treatment selection bias, a propensity score matching method was implemented. The propensity scores were estimated through a logistic regression model that predicts surgical approach by all baseline covariates of interest in this study: facility type, sex, race, insurance, income, education, urban/rural, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, year of diagnosis, primary site, histology, grade, age, and tumor size (cm). Cases from the two surgical groups were matched without replacement to each other based on the propensity scores using a greedy matching algorithm.22 The balance of covariates between the two treatment groups after matching was evaluated by calculating the standardized differences with a value < 0.10 as criteria of sufficient balance23 (See Appendix 1 for propensity score distribution and balance check after matching). The outcomes were then compared between treatment groups using the matched sample. In order to assess differences and account for the matched design, McNemar's test was used for 2 level categorical outcomes, Bowker's test of symmetry was used for more than 2 level categorical outcomes, and a paired t-test was used for numerical outcomes.

Subgroup analyses were conducted separately for patients treated in academic/research program facility and for those with ≥7 regional lymph nodes examined. The same propensity score matching as described above was implemented to balance baseline covariates between two treatment groups, and the outcomes were compared in the matched sample (See Appendix 2 and 3). All statistical analysis were conducted using SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC) and SAS macros developed by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource at the Winship Cancer Institute.24

Results

A total of 16,983 lobectomies were analyzed; 4,935 (29.1%) were performed via VATS. Descriptive statistics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1. Females comprised 54.4% of the study cohort, and the average age was 66.7 (±10.1) years. Approximately half (50.7%) of all patients had a Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score of ≥1. Adenocarcinoma was the most common type of NSCLC resected (10,300 cases; 60.6%). Mean tumor size was 2.85 (±2.38) cm; 408 cases (2.4%) were associated with positive surgical margins. The mean number of lymph nodes (LN) examined was 9.67 (±7.2), and LN upstaging occurred in a total of 2,049 (12.1%) patients. Thirty-day mortality occurred in 315 patients (1.9%) and mean postoperative length of stay was 7.0 (±6.2) days. A total of 746 (4.4%) of patients had an unplanned readmission within 30 days of surgery.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable | N=16,983 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Demographics | |||

|

| |||

| Sex | Female | 9,253 | 54.5 |

|

| |||

| Age, years (Mean, SD) | 66.7 | ±10.1 | |

|

| |||

| Race | White | 14,854 | 88.2 |

|

| |||

| Charlson/Deyo Comorbidity Score | 0 | 8,373 | 49.3 |

| 1 | 6,130 | 36.1 | |

| 2+ | 2,480 | 14.6 | |

|

| |||

| Operative Variables | |||

|

| |||

| Surgical Approacha | Thoracotomy (Open) | 12,048 | 70.9 |

| VATS | 4,935 | 29.1 | |

|

| |||

| Facility Type | Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | 5,777 | 34.0 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 9,947 | 58.6 | |

| Community Cancer Program/Other | 1,259 | 7.4 | |

|

| |||

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma | 10.300 | 60.6 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4,359 | 25.7 | |

| Other or unknown | 2,324 | 13.7 | |

|

| |||

| Tumor Size, cm (Mean, SD)b | 2.85 | ±2.38 | |

|

| |||

| Surgical Margin Positive | 408 | 2.4 | |

|

| |||

| Number of Regional LN Examined (Mean, SD) | 9.67 | ±7.2 | |

|

| |||

| Number of Regional LN Examined | 0-3 | 2,562 | 15.1 |

| 4-6 | 3,978 | 23.4 | |

| 7-9 | 3,614 | 21.3 | |

| >9 | 6,829 | 40.2 | |

|

| |||

| AJCC Pathologic N Stage | 0 | 14,934 | 87.9 |

| 1 | 1,387 | 8.2 | |

| 2 | 662 | 3.9 | |

|

| |||

| Surgical Outcomes | |||

|

| |||

| 30-day Mortality | 315 | 1.9 | |

|

| |||

| Postoperative Length of Stay, Days (Mean, SD) | 7.0 | ±6.2 | |

|

| |||

| Unplanned 30-day Readmission | 746 | 4.4 | |

VATS (Video-assisted thoracic surgery)

SD (standard deviation)

LN (Lymph node)

Following intention-to-treat, cohort includes VATS cases converted to open lobectomy

Tumor size missing in 24 patients

Demographics and outcomes based on surgical approach are summarized in Table 2. Mean age (66.6 vs. 66.8 years), race (white 88.2 vs. 88.3%), and underlying comorbidity (Charlson/Deyo score of 0; 49.3 vs. 49.4%) were similar between open and VATS (p>0.1 for all variables). VATS was more likely to be performed in an Academic/Research or Comprehensive Community Cancer Program (45.1 and 50% of all VATS, respectively). Open approach was associated with larger tumors (mean 2.9 vs. 2.7 cm). There was no difference in the rate of positive surgical margins between the two cohorts. VATS was more likely to result in a greater number of regional LN examined (≥9 LN 43.7 vs. 38.8%; p<0.001), however, nodal upstaging was more frequent in the open group (12.8 vs. 10.3%; p<.001). While the open approach resulted in longer length of hospital stay (mean 7.4 vs. 6.1 days) and greater 30-day mortality (2.1 vs. 1.3%) than VATS (all p<.001), VATS was more likely to lead to unplanned 30-day readmission (6.95 vs. 5.9%; p=0.014).

Table 2. Demographics and Outcomes by Operative Approach.

| Operative Approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Open N=12,048 | VATS N=4,935 | |||

|

| ||||

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | P-value | |

| Patient Demographics | ||||

|

| ||||

| Sex | Female | 6,476 (53.8) | 2,777 (56.3) | 0.003* |

|

| ||||

| Age, years (Mean, SD) | 66.6 (±10.2) | 66.9 (±9.9) | 0.157 | |

|

| ||||

| Race | White | 10,540 (88.2) | 4,314 (88.3) | 0.839 |

|

| ||||

| Charlson/Deyo Comorbidity Score | 0 | 5,935 (49.3) | 2,438 (49.4) | 0.281 |

| 1 | 4,322 (35.9) | 1,808 (36.6) | ||

| 2+ | 1,791 (14.9) | 689 (14.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| Operative Variables | ||||

|

| ||||

| Facility Type | Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | 3,551 (29.5) | 2,226 (45.1) | <0.001* |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 7,478 (62.1) | 2,469 (50.0) | ||

| Community Cancer Program/Other | 1,019 (8.5) | 240 (4.9) | ||

|

| ||||

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma | 7,164 (59.5) | 3,136 (63.6) | <0.001* |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 3,187 (26.5) | 1,172 (23.8) | ||

| Other | ||||

|

| ||||

| Tumor Size, cm (Mean, SD) | 2.92 (±2.5) | 2.67 (2.0) | <0.001* | |

|

| ||||

| Surgical Margin Positive | 293 (2.4) | 115 (2.33) | 0.694 | |

|

| ||||

| Number of Regional LN Examined (Mean, SD) | 9.44 (±7.2) | 10.42 (±8.14) | <0.001* | |

|

| ||||

| Number of Regional LN Examined | 0-3 | 1,876 (15.6) | 686 (13.9) | <0.001* |

| 4-6 | 2,884 (23.9) | 1,094 (22.2) | ||

| 7-9 | 2,616 (21.7) | 998 (20.2) | ||

| >9 | 4,672 (38.8) | 2,157 (43.7) | ||

|

| ||||

| AJCC Pathologic N Stage | 0 | 10,506 (87.2) | 4,428 (89.7) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 | 1,542 (12.8) | 507 (10.3) | ||

|

| ||||

| Surgical Outcomes | ||||

|

| ||||

| 30-day Mortality | 251 (2.1) | 64 (1.3) | <0.001* | |

|

| ||||

| Postoperative Length of Stay, Days (Mean, SD) | 7.35 (±SD) | 6.13 (±SD) | <0.001* | |

|

| ||||

| Unplanned 30-day Readmission | 716 (5.9) | 343 (6.95) | 0.014* | |

VATS (Video-assisted thoracic surgery)

SD (standard deviation)

LN (Lymph Node)

Significant

Following intention-to-treat, cohort includes VATS cases converted to open lobectomy

Results from the propensity-matched sample are shown in the Table 3. In 4,437 matched pairs, VATS remained associated with greater number of regional LN examined (mean 10.3 vs. 9.7; p<0.001). Nodal upstaging remained more common for open approaches (11.9 vs. 10.1%; p=0.008). Upstaging with thoracotomy compared to VATS was more common at N1, but not N2, nodal stations. Similar to the results in univariate analysis, VATS was associated with a shorter length of hospitalization by 1.0 days (p<0.001), yet still was more likely to result in unplanned 30-day readmission (5.4 vs. 3.6%; p<0.001). After matching, differences in 30-day mortality dissipated.

Table 3. Postoperative outcomes in propensity-matcheda sample.

| Outcome, n (%) | Surgical Approach: Open N=4437 | Surgical Approach: VATSb N=4437 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Lymph Nodes Examined (%) | <.001* | ||

| 0-3 | 636 (14.3) | 621 (14.0) | |

| 4-6 | 1054 (23.8) | 991 (22.3) | |

| 7-9 | 1004 (22.6) | 898 (20.3) | |

| >9 | 1743 (39.3) | 1927 (43.3) | |

| Number Lymph nodes examined (mean ± SD) | 9.7 (±7.2) | 10.3 (±7.7) | <.001* |

| Total Nodal Upstaging (%) | 529 (11.9) | 450 (10.1) | 0.008* |

| N1 upstaging | 357 (8.0) | 307 (6.9) | 0.046* |

| N2 upstaging | 172 (3.9) | 143 (3.2) | 0.098 |

| Surgical Margins Positive (%) | 93 (2.1) | 107 (2.4) | 0.322 |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 69 (1.6) | 61 (1.4) | 0.483 |

| Postoperative Length of Stay, days (mean, SD) | 7.2 (±6.4) | 6.2 (±5.8) | <0.001* |

| Unplanned 30-day Hospital Readmission (%) | 158 (3.6) | 240 (5.4) | <0.001* |

VATS (Video-assisted thoracic surgery)

SD (standard deviation)

significant

The following covariates have been balanced between the two groups: facility type, sex, race, insurance, income, education, urban/rural, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, year of diagnosis, primary site, histology, grade, age, and tumor size (cm)

Following intention-to-treat, cohort includes VATS cases converted to open lobectomy

For a sub-group of patients whose number of lymph nodes examined was ≥7 (Table 4), propensity matching (n=2825 per group) revealed that nodal upstaging remained more common following open vs. VATS (14.0 vs 12.1%; p=0.03). However, for patients who were treated in an Academic/Research Program Facility (Table 5), the difference in nodal upstaging during VATS vs open lobectomy was no longer significant (10.5 vs. 12.2%, p=0.08; n=2008 per group). This subgroup analysis also revealed that the risk of unplanned 30-day readmission was no longer statistically different between the VATS vs. open cohorts. It is possible that the difference may become significant in a larger study cohort.

Table 4. Postoperative outcomes in propensity-matcheda sample where number of lymph nodes examined ≥7.

| Outcome, n (%) | Surgical Approach: Open N=2825 | Surgical Approach: VATSb N=2825 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lymph nodes examined (%) | 0.027* | ||

| 7-9 | 977 (34.6) | 898 (31.8) | |

| >9 | 1,848 (65.4) | 1,927 (68.2) | |

| Number lymph nodes examined (mean ± SD) | 13.34 (±7.0) | 13.95 (±7.4) | 0.001* |

| Total Nodal Upstaging (%) | 396 (14.0) | 341 (12.1) | 0.031* |

| N1 upstaging | 257 (9.1) | 222 (7.9) | 0.106 |

| N2 upstaging | 139 (4.9) | 119 (4.21) | 0.214 |

| Surgical Margins Positive (%) | 65 (2.3) | 63 (2.2) | 0.859 |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 43 (1.5) | 39 (1.4) | 0.659 |

| Postoperative Length of Stay, days (mean, SD) | 7.24 (±6.6) | 6.03 (±5.8) | <0.001* |

| Unplanned 30-day Hospital Readmission (%) | 115 (4.1) | 148 (5.24) | 0.08 |

VATS (Video-assisted thoracic surgery)

SD (standard deviation)

significant

The following covariates have been balanced between the two groups: facility type, sex, race, insurance, income, education, urban/rural, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, year of diagnosis, primary site, histology, grade, age, and tumor size (cm)

Following intention-to-treat, cohort includes VATS cases converted to open lobectomy

Table 5. Postoperative outcomes in propensity-matcheda sample for Academic/Research programs.

| Outcome, n (%) | Surgical Approach: Open N=2008 | Surgical Approach: VATSb N=2008 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Lymph Nodes Examined (%) | 0.032 | ||

| 0-3 | 250 (12.5) | 207 (10.3) | |

| 4-6 | 403 (20.1) | 373 (18.6) | |

| 7-9 | 436 (21.7) | 405 (20.2) | |

| >9 | 919 (45.8) | 1,023 (51.0) | |

| Number Lymph nodes examined (mean ± SD) | 10.71 (±7.9) | 11.57 (±8.4) | <0.001* |

| Total Nodal Upstaging (%) | 245 (12.2) | 210 (10.5) | 0.084 |

| N1 upstaging | 170 (8.5) | 140 (7.0) | 0.077 |

| N2 upstaging | 75 (3.7) | 70 (3.5) | 0.671 |

| Surgical Margins Positive (%) | 37 (1.8) | 41 (2.0) | 0.651 |

| 30-day Mortality (%) | 29 (1.4) | 21 (1.1) | 0.258 |

| Postoperative Length of Stay, days (mean, SD) | 7.29 (±7.7) | 5.9 (±5.5) | <0.001* |

| Unplanned 30-day Hospital Readmission (%) | 68 (3.4) | 92 (4.6) | 0.255 |

VATS (Video-assisted thoracic surgery)

SD (standard deviation)

significant

The following covariates have been balanced between the two groups: facility type, sex, race, insurance, income, education, urban/rural, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, year of diagnosis, primary site, histology, grade, age, and tumor size (cm)

Following intention-to-treat, cohort includes VATS cases converted to open lobectomy

Discussion

Results from the current study differ somewhat from what has previously been published. Our propensity-matched analysis demonstrates that VATS actually yielded a higher mean number of overall lymph nodes examined compared to open thoracotomy (10.3 ± 7.7 vs. 9.7 ± 7.2; p<0.001). Although the current study is unable to extrapolate why a minimally invasive approach would lead to more lymph nodes examined, it is possible that more lymph nodes are fragmented during VATS than thoracotomy. More importantly, however, this result remained consistent on both sub-group analyses for ≥7 lymph nodes examined and academic/research programs, indicating that a minimally invasive approach does not limit the overall extent of lymph node dissection.

On the other hand, despite the greater number of lymph nodes removed during the VATS approach, our data show that overall nodal upstaging remained more common following an open approach (11.9 vs. 10.1%; p=0.008). It is possible that patients undergoing thoracotomy had larger, more central tumors. While tumor size is controlled for within the propensity model we present, unfortunately the centrality of the tumor is not obtainable from the data within the NCDB. Similar to the results from the STS GTSD study,16 our data also reveal that the rate of N1 upstaging remained significantly more common following open vs. VATS approach (8.0 vs. 6.9%; p=0.046) and there was no significant difference in the rate of N2 upstaging between the two cohorts. Similar results were noted on subgroup analysis for ≥7 lymph nodes examined; however, the difference between the two groups dissipated when analyzing academic/research programs only. These data may be indicative of differences in minimally invasive surgeon training and/or surgeon specialty at different types of centers.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality in men and women in the U.S., with an estimated 221,200 new cases and 158,040 deaths expected in 2015.25 The advanced stage at which the majority of lung cancers present accounts largely for the poor survival rate of approximately 15% at 5 years; chemotherapy and radiation provide only small improvements for advanced disease.26-29 However, resection of early stage lung cancer is associated with cure rates of 77-92%.30-32 To ensure appropriate surgical treatment of early stage NSCLC, an adequate lymphadenectomy is imperative to properly stage patients and guide adjuvant therapy.

Currently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that “N1 and N2 nodal resection and mapping should be a routine component of lung cancer resections – a minimum of three N2 stations sampled or complete lymph node dissection.”33 There are currently no quality metrics in existence that recommend a minimum number of lymph nodes which should be resected during surgery for NSCLC to allow for adequate staging and possible survival benefit. Further, it remains uncertain as how best to measure the extent of lymph node evaluation: number of nodes samples, lymph node stations evaluated, or lymph node weight. Multiple studies within the literature have failed to establish a survival benefit associated with the number of lymph nodes examined in VATS vs. open lobectomy for early stage lung cancer. In a retrospective propensity-matched analysis, Lee et al concluded that while thoracotomy resulted in a more thorough lymph node evaluation (14.3 vs. 11.3 lymph nodes; p=0.001), VATS lobectomy offered similar overall and disease-free survival rates.17 Merritt and colleagues echoed these findings in their retrospective, single-institution analysis of 129 clinical stage N0 NSCLC patients; they concluded that more nodes were evaluated in the open vs. VATS cohort, but there was no difference in 3-year survival.18

A retrospective, single-institution study from 201015 compared the adequacy of lymph node assessment between VATS (n=79) and open (n=464) approaches demonstrated that [1] fewer total number of lymph nodes were sampled with VATS compared with thoracotomy (7.4 ± 0.6 vs. 8.9 ± 0.2, respectively; p=0.029); [2] there was no difference in N1 sampling (5.2 ± 3.6 vs. 4.9 ± 4.2; p=0.592; and [3] fewer mediastinal (N2) nodes were sampled with VATS than with thoracotomy (2.5 ± 3.0 vs. 3.7 ± 3.3, respectively; p=0.004).

A more recent study from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) General Thoracic Surgery Database (GTSD) sought to determine the frequency of nodal metastases identified in clinically node-negative tumors by open (n=7,137) and VATS (n=1,024) approaches.16 The authors report that nodal upstaging was observed in 14.3% of open cases compared to 11.6% of VATS (p < .001). Upstaging from N0 to N1 (hilar and peribronchial) was more common in the open group compared to VATS (9.3 vs. 6.7%; p<.001); however, upstaging from N0 to N2 (mediastinal) was not different (open-5.0% and VATS-4.9%; p=0.52). In propensity-matched adjustment, hilar (N1) upstaging remained less common for VATS (6.8 vs. 9%, p=0.002). The study concluded that lower rates of N1 upstaging in the VATS group may indicate variability in the completeness of hilar and peribronchial lymph node dissection. Moreover, they note that the difference in upstaging disappeared when controlling for surgeons who perform the majority of their cases using VATS.

There are numerous additional studies that demonstrate similar survival rates for VATS vs. open approaches for NSCLC. A 2009 meta-analysis comparing 21 studies investigating surgical outcomes following VATS vs. open lobectomy for early stage NSCLC concluded there was no difference in locoregional recurrence based on operative approach, but also reported that VATS appears to result in reduced systemic recurrence and improved 5-year mortality rates.12 Three more recent series also concluded that there was no difference in long-term survival following VATS vs. open thoracotomy for lobectomy in NSCLC patients.34-36

On a final interesting note, we found that the rate of unplanned 30-day readmission was higher for patients following VATS compared to open lobectomy. This result has not been previously published from studies utilizing smaller, academic center-focused or single institution retrospective datasets. In this study, within the subgroup analysis controlling for academic/research center type, the difference in readmission rate was no longer significant (Table 5). These results demonstrate that in a sample more generalizable to a national population, surgical outcomes may differ significantly across center type, and serve to support the hypothesis that center type is a marker for differences in surgeon practice resulting in superior patient outcomes.

We acknowledge that the current study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective analysis of a de-identified dataset. While we utilized propensity-score matching with the goal of eliminating potential known confounding variables between the two groups, this study cannot account for unmeasured confounding. Second, the lack of long-term survival data for our cohort limits the ability to conclude whether or not the differences in nodal upstaging directly impacts overall patient survival. Third, the NCDB lacks clinical details on patients such as pulmonary function tests, specific medical comorbidities beyond comorbidity scoring, specific nodal stations examined, and centrality of tumor. Fourth, we do not have preoperative staging data on patients within the cohort. It is likely that certain patients underwent endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS), mediastinoscopy and/or PET scan that influenced preoperative clinical staging. Lastly, the database does not contain information on surgeon specialty training or the volume of VATS and open lobectomies at specific institutions.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the current study utilizes a large generalizable national dataset that contains detailed treatment and staging data. As data are updated in the NCDB, long-term survival data will be available within our study cohort and future investigations will focus on the relationship between lymph node upstaging and overall survival.

Conclusions

From these national data, nodal upstaging was more frequently observed with open thoracotomy compared to VATS for early stage lung cancer, even when a similar number of lymph nodes had been examined. However, nodal upstaging appears to be impacted by facility type, which may represent a surrogate for minimally invasive expertise. Standardized quality assurance of lymph node staging during VATS lobectomy is needed with the goal of eliminating differences in staging when compared to an open approach. An analysis of long-term survival between VATS and thoracotomy approaches to lobectomy for early stage lung cancer remains a critical unmet need in determining optima treatment for NSCLC, to ensure that minimally invasive approaches provide equivalent tumor control compared to open approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/NCI under award number P30CA138292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The data used in the study are derived from a de-identified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology used, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

Appendix 1

Balance Check in Matched Sample Based on Surgical Approach.

| Surgical Approach | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Covariate | Level | Statistics | Open N=4437 | Minimally Invasive N=4437 |

P-value* | Standardized Difference |

| Facility Type | Community Cancer Program/Other | N (Col%) | 208 (4.69) | 208 (4.69) | 0.999 | 0.000 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | N (Col%) | 2223 (50.1) | 2221 (50.06) | 0.001 | ||

| Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | N (Col%) | 2006 (45.21) | 2008 (45.26) | 0.001 | ||

| Sex | Male | N (Col%) | 1962 (44.22) | 1933 (43.57) | 0.535 | 0.013 |

| Female | N (Col%) | 2475 (55.78) | 2504 (56.43) | 0.013 | ||

| Race: White | No | N (Col%) | 511 (11.52) | 530 (11.95) | 0.531 | 0.013 |

| Yes | N (Col%) | 3926 (88.48) | 3907 (88.05) | 0.013 | ||

| Insurance | Not Insured | N (Col%) | 89 (2.01) | 90 (2.03) | 0.965 | 0.002 |

| Private Insurance | N (Col%) | 1506 (33.94) | 1517 (34.19) | 0.005 | ||

| Govt. Insurance | N (Col%) | 2842 (64.05) | 2830 (63.78) | 0.006 | ||

| Income | < $30,000 | N (Col%) | 554 (12.49) | 544 (12.26) | 0.798 | 0.007 |

| $30,000 - $34,999 | N (Col%) | 732 (16.5) | 751 (16.93) | 0.011 | ||

| $35,000 - $45,999 | N (Col%) | 1179 (26.57) | 1207 (27.2) | 0.014 | ||

| $46,000 + | N (Col%) | 1972 (44.44) | 1935 (43.61) | 0.017 | ||

| Education | >=29% | N (Col%) | 645 (14.54) | 652 (14.69) | 0.917 | 0.004 |

| 20-28.9% | N (Col%) | 973 (21.93) | 963 (21.7) | 0.005 | ||

| 14-19.9% | N (Col%) | 1112 (25.06) | 1137 (25.63) | 0.013 | ||

| < 14% | N (Col%) | 1707 (38.47) | 1685 (37.98) | 0.010 | ||

| Urban/Rural | Metro Area | N (Col%) | 3761 (84.76) | 3729 (84.04) | 0.271 | 0.020 |

| Urban | N (Col%) | 615 (13.86) | 629 (14.18) | 0.009 | ||

| Rural | N (Col%) | 61 (1.37) | 79 (1.78) | 0.033 | ||

| Charlson/Deyo Score | 0 | N (Col%) | 2182 (49.18) | 2172 (48.95) | 0.977 | 0.005 |

| 1 | N (Col%) | 1621 (36.53) | 1629 (36.71) | 0.004 | ||

| 2+ | N (Col%) | 634 (14.29) | 636 (14.33) | 0.001 | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | 2010 | N (Col%) | 1935 (43.61) | 1969 (44.38) | 0.467 | 0.015 |

| 2011 | N (Col%) | 2502 (56.39) | 2468 (55.62) | 0.015 | ||

| Primary Site | C341 Left: Upper lobe, lung; Lingula; Apex; Pancoast tumor | N (Col%) | 1082 (24.39) | 1083 (24.41) | 0.880 | 0.001 |

| C342: Middle lobe, lung (Right lung only) | N (Col%) | 311 (7.01) | 308 (6.94) | 0.003 | ||

| C343 Right: Lower lobe, lung; Base | N (Col%) | 795 (17.92) | 798 (17.99) | 0.002 | ||

| C343 Left: Lower lobe, lung; Base | N (Col%) | 685 (15.44) | 662 (14.92) | 0.014 | ||

| C348: Overlapping lesion of lung | N (Col%) | 29 (0.65) | 20 (0.45) | 0.027 | ||

| C349: Lung, NOS; Bronchus, NOS | N (Col%) | 37 (0.83) | 39 (0.88) | 0.005 | ||

| C341 Right: Upper lobe, lung; Lingula; Apex; Pancoast tumor | N (Col%) | 1498 (33.76) | 1527 (34.42) | 0.014 | ||

| Histology | Adenocarcinomas | N (Col%) | 2848 (64.19) | 2834 (63.87) | 0.900 | 0.007 |

| Adenosquamous carcinomas | N (Col%) | 108 (2.43) | 94 (2.12) | 0.021 | ||

| Large cell carcinomas | N (Col%) | 92 (2.07) | 100 (2.25) | 0.012 | ||

| Other tumors, including but not restricted to, spindle cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoidmalignanci | N (Col%) | 287 (6.47) | 293 (6.6) | 0.005 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinomas | N (Col%) | 1038 (23.39) | 1055 (23.78) | 0.009 | ||

| Unknown histology | N (Col%) | 64 (1.44) | 61 (1.37) | 0.006 | ||

| Grade | 1 | N (Col%) | 830 (18.71) | 833 (18.77) | 0.968 | 0.002 |

| 2 | N (Col%) | 2035 (45.86) | 2008 (45.26) | 0.012 | ||

| 3 | N (Col%) | 1287 (29.01) | 1315 (29.64) | 0.014 | ||

| 4 | N (Col%) | 40 (0.9) | 41 (0.92) | 0.002 | ||

| Unknown, high grade dysplasia | N (Col%) | 245 (5.52) | 240 (5.41) | 0.005 | ||

| Patient Age | Mean (Std) | 66.9 (10.02) | 66.86 (9.93) | 0.856 | 0.004 | |

| Size of Tumor (cm) | Mean (Std) | 2.73 (1.75) | 2.67 (1.82) | 0.121 | 0.033 | |

The parametric p value is calculated by ANOVA for numerical covariates and Chi-Square test for categorical covariates.

Appendix 2

Balance Check of Matched Sample Based on Surgical Approach and Academic Program Only.

| Surgical Approach | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Covariate | Level | Statistics | Open N=2008 | Minimally Invasive N=2008 |

P-value* | Standardized Difference |

| Sex | Male | N (Col%) | 885 (44.07) | 861 (42.88) | 0.445 | 0.024 |

| Female | N (Col%) | 1123 (55.93) | 1147 (57.12) | 0.024 | ||

| Race: White | No | N (Col%) | 307 (15.29) | 308 (15.34) | 0.965 | 0.001 |

| Yes | N (Col%) | 1701 (84.71) | 1700 (84.66) | 0.001 | ||

| Insurance | Not Insured | N (Col%) | 26 (1.29) | 34 (1.69) | 0.566 | 0.033 |

| Private Insurance | N (Col%) | 708 (35.26) | 698 (34.76) | 0.010 | ||

| Govt. Insurance | N (Col%) | 1274 (63.45) | 1276 (63.55) | 0.002 | ||

| Income | < $30,000 | N (Col%) | 285 (14.19) | 269 (13.4) | 0.766 | 0.023 |

| $30,000 - $34,999 | N (Col%) | 338 (16.83) | 332 (16.53) | 0.008 | ||

| $35,000 - $45,999 | N (Col%) | 489 (24.35) | 514 (25.6) | 0.029 | ||

| $46,000 + | N (Col%) | 896 (44.62) | 893 (44.47) | 0.003 | ||

| Education | >=29% | N (Col%) | 310 (15.44) | 307 (15.29) | 0.994 | 0.004 |

| 20-28.9% | N (Col%) | 425 (21.17) | 420 (20.92) | 0.006 | ||

| 14-19.9% | N (Col%) | 506 (25.2) | 512 (25.5) | 0.007 | ||

| < 14% | N (Col%) | 767 (38.2) | 769 (38.3) | 0.002 | ||

| Urban/Rural | Metro Area | N (Col%) | 1710 (85.16) | 1704 (84.86) | 0.962 | 0.008 |

| Urban | N (Col%) | 275 (13.7) | 280 (13.94) | 0.007 | ||

| Rural | N (Col%) | 23 (1.15) | 24 (1.2) | 0.005 | ||

| Charlson/Deyo Score | 0 | N (Col%) | 1014 (50.5) | 1023 (50.95) | 0.960 | 0.009 |

| 1 | N (Col%) | 706 (35.16) | 700 (34.86) | 0.006 | ||

| 2+ | N (Col%) | 288 (14.34) | 285 (14.19) | 0.004 | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | 2010 | N (Col%) | 882 (43.92) | 899 (44.77) | 0.589 | 0.017 |

| 2011 | N (Col%) | 1126 (56.08) | 1109 (55.23) | 0.017 | ||

| Primary Site | C341 Left: Upper lobe, lung; Lingula; Apex; Pancoast tumor | N (Col%) | 508 (25.3) | 494 (24.6) | 0.706 | 0.016 |

| C342: Middle lobe, lung (Right lung only) | N (Col%) | 129 (6.42) | 125 (6.23) | 0.008 | ||

| C343 Right: Lower lobe, lung; Base | N (Col%) | 351 (17.48) | 341 (16.98) | 0.013 | ||

| C343 Left: Lower lobe, lung; Base | N (Col%) | 249 (12.4) | 280 (13.94) | 0.046 | ||

| C348: Overlapping lesion of lung | N (Col%) | 8 (0.4) | 4 (0.2) | 0.037 | ||

| C349: Lung, NOS; Bronchus, NOS | N (Col%) | 18 (0.9) | 21 (1.05) | 0.015 | ||

| C341 Right: Upper lobe, lung; Lingula; Apex; Pancoast tumor | N (Col%) | 745 (37.1) | 743 (37) | 0.002 | ||

| Grade | 1 | N (Col%) | 390 (19.42) | 393 (19.57) | 0.990 | 0.004 |

| 2 | N (Col%) | 884 (44.02) | 891 (44.37) | 0.007 | ||

| 3 | N (Col%) | 595 (29.63) | 591 (29.43) | 0.004 | ||

| 4 | N (Col%) | 12 (0.6) | 13 (0.65) | 0.006 | ||

| Unknown, high grade dysplasia | N (Col%) | 127 (6.32) | 120 (5.98) | 0.015 | ||

| Patient Age | Mean (Std) | 66.29 (10.25) | 66.29 (10.06) | 0.994 | 0.000 | |

| Size of Tumor (cm) | Mean (Std) | 2.67 (1.78) | 2.62 (1.63) | 0.404 | 0.026 | |

The parametric p value is calculated by ANOVA for numerical covariates and Chi-Square test for categorical covariates.

Appendix 3

Balance Check of Matched Sample Based on Surgical Approach and LN 7.

| Surgical Approach | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Covariate | Level | Statistics | Open N=2825 | Minimally Invasive N=2825 |

P-value* | Standardized Difference |

| Facility Type | Community Cancer Program/Other | N (Col%) | 95 (3.36) | 113 (4) | 0.331 | 0.034 |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | N (Col%) | 1321 (46.76) | 1284 (45.45) | 0.026 | ||

| Academic/Research Program (Includes NCI) | N (Col%) | 1409 (49.88) | 1428 (50.55) | 0.013 | ||

| Sex | Male | N (Col%) | 1262 (44.67) | 1228 (43.47) | 0.362 | 0.024 |

| Female | N (Col%) | 1563 (55.33) | 1597 (56.53) | 0.024 | ||

| Race: White | No | N (Col%) | 353 (12.5) | 348 (12.32) | 0.840 | 0.005 |

| Yes | N (Col%) | 2472 (87.5) | 2477 (87.68) | 0.005 | ||

| Insurance | Not Insured | N (Col%) | 49 (1.73) | 57 (2.02) | 0.679 | 0.021 |

| Private Insurance | N (Col%) | 987 (34.94) | 970 (34.34) | 0.013 | ||

| Govt. Insurance | N (Col%) | 1789 (63.33) | 1798 (63.65) | 0.007 | ||

| Income | < $30,000 | N (Col%) | 339 (12) | 347 (12.28) | 0.834 | 0.009 |

| $30,000 - $34,999 | N (Col%) | 425 (15.04) | 445 (15.75) | 0.020 | ||

| $35,000 - $45,999 | N (Col%) | 792 (28.04) | 792 (28.04) | 0.000 | ||

| $46,000 + | N (Col%) | 1269 (44.92) | 1241 (43.93) | 0.020 | ||

| Education | >=29% | N (Col%) | 395 (13.98) | 414 (14.65) | 0.883 | 0.019 |

| 20-28.9% | N (Col%) | 601 (21.27) | 606 (21.45) | 0.004 | ||

| 14-19.9% | N (Col%) | 705 (24.96) | 701 (24.81) | 0.003 | ||

| < 14% | N (Col%) | 1124 (39.79) | 1104 (39.08) | 0.014 | ||

| Urban/Rural | Metro Area | N (Col%) | 2411 (85.35) | 2390 (84.6) | 0.737 | 0.021 |

| Urban | N (Col%) | 373 (13.2) | 392 (13.88) | 0.020 | ||

| Rural | N (Col%) | 41 (1.45) | 43 (1.52) | 0.006 | ||

| Charlson/Deyo Score | 0 | N (Col%) | 1445 (51.15) | 1436 (50.83) | 0.846 | 0.006 |

| 1 | N (Col%) | 997 (35.29) | 991 (35.08) | 0.004 | ||

| 2+ | N (Col%) | 383 (13.56) | 398 (14.09) | 0.015 | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | 2010 | N (Col%) | 1236 (43.75) | 1253 (44.35) | 0.649 | 0.012 |

| 2011 | N (Col%) | 1589 (56.25) | 1572 (55.65) | 0.012 | ||

| Primary Site | C341 Left: Upper lobe, lung; Lingula; Apex; Pancoast tumor | N (Col%) | 770 (27.26) | 749 (26.51) | 0.953 | 0.017 |

| C342: Middle lobe, lung (Right lung only) | N (Col%) | 136 (4.81) | 133 (4.71) | 0.005 | ||

| C343 Right: Lower lobe, lung; Base | N (Col%) | 511 (18.09) | 495 (17.52) | 0.015 | ||

| C343 Left: Lower lobe, lung; Base | N (Col%) | 403 (14.27) | 422 (14.94) | 0.019 | ||

| C348: Overlapping lesion of lung | N (Col%) | 17 (0.6) | 14 (0.5) | 0.014 | ||

| C349: Lung, NOS; Bronchus, NOS | N (Col%) | 22 (0.78) | 23 (0.81) | 0.004 | ||

| C341 Right: Upper lobe, lung; Lingula; Apex; Pancoast tumor | N (Col%) | 966 (34.19) | 989 (35.01) | 0.017 | ||

| Histology | Adenocarcinomas | N (Col%) | 1822 (64.5) | 1827 (64.67) | 0.920 | 0.004 |

| Adenosquamous carcinomas | N (Col%) | 61 (2.16) | 66 (2.34) | 0.012 | ||

| Large cell carcinomas | N (Col%) | 71 (2.51) | 67 (2.37) | 0.009 | ||

| Other tumors, including but not restricted to, spindle cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoidmalignanci | N (Col%) | 146 (5.17) | 152 (5.38) | 0.010 | ||

| Squamous cell carcinomas | N (Col%) | 695 (24.6) | 676 (23.93) | 0.016 | ||

| Unknown histology | N (Col%) | 30 (1.06) | 37 (1.31) | 0.023 | ||

| Grade | 1 | N (Col%) | 517 (18.3) | 519 (18.37) | 0.975 | 0.002 |

| 2 | N (Col%) | 1320 (46.73) | 1305 (46.19) | 0.011 | ||

| 3 | N (Col%) | 833 (29.49) | 836 (29.59) | 0.002 | ||

| 4 | N (Col%) | 31 (1.1) | 31 (1.1) | 0.000 | ||

| Unknown, high grade dysplasia | N (Col%) | 124 (4.39) | 134 (4.74) | 0.017 | ||

| Patient Age | Mean (Std) | 66.96 (9.89) | 66.89 (9.93) | 0.804 | 0.007 | |

| Size of Tumor (cm) | Mean (Std) | 2.82 (1.71) | 2.78 (2.04) | 0.455 | 0.020 | |

The parametric p value is calculated by ANOVA for numerical covariates and Chi-Square test for categorical covariates.

Footnotes

Oral presentation: 41st Annual Meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association

Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McKenna RJ, Jr, Houck W, Fuller CB. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: experience with 1,100 cases. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006;81:421–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.078. discussion 5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onaitis MW, Petersen RP, Balderson SS, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is a safe and versatile procedure: experience with 500 consecutive patients. Annals of surgery. 2006;244:420–5. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234892.79056.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul S, Altorki NK, Sheng S, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: a propensity-matched analysis from the STS database. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2010;139:366–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson SJ, Herndon JE, 2nd, D'Amico TA, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: report of CALGB 39802--a prospective, multi-institution feasibility study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:4993–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattaneo SM, Park BJ, Wilton AS, et al. Use of video-assisted thoracic surgery for lobectomy in the elderly results in fewer complications. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2008;85:231–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.080. discussion 5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grogan EL, Jones DR. VATS lobectomy is better than open thoracotomy: what is the evidence for short-term outcomes? Thoracic surgery clinics. 2008;18:249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagahiro I, Andou A, Aoe M, Sano Y, Date H, Shimizu N. Pulmonary function, postoperative pain, and serum cytokine level after lobectomy: a comparison of VATS and conventional procedure. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001;72:362–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicastri DG, Wisnivesky JP, Litle VR, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy: report on safety, discharge independence, pain, and chemotherapy tolerance. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2008;135:642–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson SJ, Meyers BF, Gunnarsson CL, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy is less costly and morbid than open lobectomy: a retrospective multiinstitutional database analysis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2012;93:1027–32. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villamizar NR, Darrabie MD, Burfeind WR, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity compared with thoracotomy. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2009;138:419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitson BA, Groth SS, Duval SJ, Swanson SJ, Maddaus MA. Surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review of the video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus thoracotomy approaches to lobectomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2008;86:2008–16. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.009. discussion 16-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, McCaughan BC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:2553–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwig MS, Goodman M, Miller DL, Johnstone PA. Postoperative survival and the number of lymph nodes sampled during resection of node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128:1545–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varlotto JM, Recht A, Nikolov M, Flickinger JC, Decamp MM. Extent of lymphadenectomy and outcome for patients with stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:851–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denlinger CE, Fernandez F, Meyers BF, et al. Lymph node evaluation in video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy versus lobectomy by thoracotomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010;89:1730–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.02.094. discussion 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boffa DJ, Kosinski AS, Paul S, Mitchell JD, Onaitis M. Lymph node evaluation by open or video-assisted approaches in 11,500 anatomic lung cancer resections. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2012;94:347–53. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.059. discussion 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee PC, Nasar A, Port JL, et al. Long-term survival after lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer by video-assisted thoracic surgery versus thoracotomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;96:951–60. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.04.104. discussion 60-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merritt RE, Hoang CD, Shrager JB. Lymph node evaluation achieved by open lobectomy compared with thoracoscopic lobectomy for N0 lung cancer. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;96:1171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsim S, O'Dowd CA, Milroy R, Davidson S. Staging of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a review. Respiratory medicine. 2010;104:1767–74. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2007;2:706–14. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai K, van Dyk DA. Causal Inference With General Treatment Regimes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2004;99:854–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergstralh EJ, Kosanke JL. Computerized matching of cases to controls. Rochester, MN: Department of Health Science Research, Mayo Clinic; 1995. Apr, Report No.: 56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC. The relative ability of different propensity score methods to balance measured covariates between treated and untreated subjects in observational studies. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2009;29:661–77. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09341755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickleach D, Liu Y, Shrewsberry A, Ogan K, Kim S, Wang Z. SAS® Macros to Conduct Common Biostatistical Analyses and Generate Reports. SESUG 2013: The Proceedings of the SouthEast SAS Users Group; St. Pete Beach, FL. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah BR, Laupacis A, Hux JE, Austin PC. Propensity score methods gave similar results to traditional regression modeling in observational studies: a systematic review. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2005;58:550–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jett JR, Schild SE, Keith RL, Kesler KA. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, stage IIIB: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. (2nd) 2007;132:266S–76S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lester JF, Macbeth FR, Toy E, Coles B. Palliative radiotherapy regimens for non-small cell lung cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006:CD002143. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002143.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowell NP, O'Rourke NP. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004:CD002140. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002140.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Socinski MA, Crowell R, Hensing TE, et al. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, stage IV: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. (2nd) 2007;132:277S–89S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Libby DM, Pasmantier MW, Smith JP, Miettinen OS. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355:1763–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee PC, Korst RJ, Port JL, Kerem Y, Kansler AL, Altorki NK. Long-term survival and recurrence in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer 1 cm or less in size. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2006;132:1382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rami-Porta R, Ball D, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the T descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2007;2:593–602. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807a2f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekhon JS. Multivariate and Propensity Score Matching Software with Automated Balance Optimization: The Matching Package for R. J Stat Softw. 2011;42:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao C, Zhu ZH, Yan TD, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open thoracotomy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a propensity score analysis based on a multi-institutional registry. European journal of cardiothoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2013;44:849–54. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berry MF, D'Amico TA, Onaitis MW, Kelsey CR. Thoracoscopic approach to lobectomy for lung cancer does not compromise oncologic efficacy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2014;98:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higuchi M, Yaginuma H, Yonechi A, et al. Long-term outcomes after video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) lobectomy versus lobectomy via open thoracotomy for clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery. 2014;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.