SUMMARY

PG0162, annotated as an extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor in Porphyromonas gingivalis, is composed of 193 amino acids. As previously reported, the PG0162-deficient mutant, P. gingivalis FLL350 showed significant reduction in gingipain activity compared to the parental strain. Because this ECF sigma factor could be involved in the virulence regulation in P. gingivalis, its genetic properties were further characterized. A 5’-RACE analysis showed that the start of transcription of the PG0162 gene occurred from a guanine (G) residue 69 nucleotides upstream of the ATG translation initiation codon. The function of PG0162 as a sigma factor was confirmed in a run-off in vitro transcription assay using the purified rPG0162 and RNAP core enzyme from E.coli with the PG0162 promoter as template. Since an appropriate PG0162 inducing environmental signal is unknown, a strain overexpressing the PG0162 gene designated P. gingivalis FLL391 was created. Compared to the wild-type strain, transcriptome analysis of P. gingivalis FLL391 showed that approximately 24% of the genome displayed altered gene expression (260 upregulated genes; 286 downregulated genes). Two other ECF sigma factors (PG0985 and PG1660) were upregulated more than 2 fold. The autoregulation of PG0162 was confirmed with the binding of the rPG0162 protein to the PG0162 promoter in electrophoretic mobility shift assay. In addition, the rPG0162 protein also showed the ability to bind to the promoter region of two genes (PG0521 and PG1167) that were most upregulated in P. gingivalis FLL391. Taken together, our data suggest that PG0162 is a sigma factor that may play an important role in the virulence regulatory network in P. gingivalis.

Keywords: ECF sigma factor, Virulence, Periodontitis, Sigma 24

Introduction

In the United States, over 64.7 million people are affected by periodontitis, a chronic infection-induced inflammatory condition involving the tissues supporting the teeth (Eke et al., 2012). Porphyromonas gingivalis, a black-pigmented anaerobic bacterium is recognized as a significant etiological agent involved in the initiation and progression of periodontal diseases and is associated with other inflammatory systemic diseases including cardiovascular diseases and rheumatoid arthritis (Detert et al., 2010; Inaba & Amano, 2010). In the harsh microenvironment of the periodontal pocket, the survival and growth of P. gingivalis require the activation of a (an) protective/adaptive mechanism(s) that must be rapidly modulated (Henry et al., 2012; Kolenbrander, 2000). The modulation of adaptive responses is intricately associated with gene regulation involving diverse molecular events at the transcriptional, translational and post-translational levels.

Multiple signaling pathways will enable bacteria to alter their gene expression in response to environmental signals. One type of response mechanism is facilitated by extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor, which is the largest group of alternative sigma factors and plays a key role in adaption to environmental conditions (Helmann, 2002). ECF sigma factors act in response to environmental signal stress by binding the core RNA polymerase complex and initiating the transcription of a limited set of genes required for growth and survival of the bacteria (Helmann, 2002).

ECF sigma factors are the smallest σ70 family proteins and contain only two (σ2 and σ4) of the four conserved regions compared to the primary sigma factor (Mascher, 2013). The gene coding for ECF sigma factor usually form an operon with its anti-sigma factor encoding gene. The ECF sigma factor is regulated by its cognate anti-sigma factor protein, which is localized to the cytoplasmic membrane with direct binding of the ECF sigma factor, resulting in sequestration and inhibition of sigma factor activity (Ho & Ellermeier, 2012). Under environmental signal stress conditions, the ECF sigma factor is released from the cognate anti-sigma factor and competitively binds to the RNA polymerase core enzyme, resulting in transcription initiation of the stimulus-responsive gene(s), including its own operon in most cases. The anti-sigma factors are regulated by the mechanism of intra-membrane proteolysis (Ho & Ellermeier, 2012), or by phosphorylation dependent response regulator (Francez-Charlot et al., 2009).

ECF sigma factors have been reported to be involved in virulence regulation in pathogenic bacteria including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis (Hahn et al., 2005; Le et al., 2010; Llamas et al., 2009; Shaw et al., 2008; Wood & Ohman, 2009). The P. gingivalis W83 genome encodes eight sigma factors, six of which belong to the ECF sigma factor subfamily (PG0162, PG0214, PG0985, PG1318, PG1660, and PG1827 [SigH]) (Nelson et al., 2003; Yanamandra et al., 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated a role for several of the ECF sigma factors for survival of P. gingivalis in the presence of oxygen, hydrogen peroxide, and thiol-induced stress (Dou et al., 2010; Yanamandra et al., 2012). In addition, its function as a positive regulator of hemin uptake and virulence regulation in this bacterium is documented (Yanamandra et al., 2012). The PGN_0274 mutant in P. gingivalis ATCC33277 showed increased biofilm production compared to the wild-type in a recent study (Onozawa, 2015). There is still however a gap in our comprehensive understanding of the functional role of many of these ECF sigma factors in the response of P. gingivalis to environmental stress. Our earlier report demonstrated that the P. gingivalis PG0162-deficient mutant designated FLL350 showed decreased gingipain, hemagglutination and hemolytic activities, and also showed a similar sensitivity to H2O2 compared the parent strain (Dou et al., 2010). The regulatory role of PG0162 in virulence observed in this study appeared to be occurring at the post-transcriptional level (Dou et al., 2010). Bioinformatics analysis revealed that this protein has a 26% homology to sigma W (σ-24) from E. coli. Further, PG0162 is missing a putative cognate anti-sigma factor in contrast to the other ECF sigma factors in the P. gingivalis genome (Nelson et al., 2003). Taken together, it is likely that PG0162 may be involved in a unique and complex regulatory network/mechanism. In this report, we have further characterized PG0162. As a transcriptional regulator with DNA promoter binding properties, we have demonstrated its sigma factor function and its regulatory profile in P. gingivalis.

Methods and Materials

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. gingivalis strains were cultured as described previously (Dou et al., 2010). In brief, P. gingivalis was grown in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with yeast extract (0.5%), hemin (5 µg/ml), vitamin K (0.5 µg/ml), and DL-cysteine (0.1%). The bacterial cells were incubated in an anaerobic chamber in 10% H2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2 at 37 °C. Erythromycin and tetracycline were used at concentrations of 10 µg/ml and 0.3 µg/ml respectively.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strains and plasmids | Relevant characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. gingivalis | ||

| W83 | Wild-type | Dou et al. (2010) |

| FLL350 | ΔPG0162::ermF | Dou et al. (2010) |

| FLL391 | W83 carrying pT-COW-0162 | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| FLL386 | BL21 with pET0162 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pT-COW | Shuttle vector, Apr, tetQ, tet | Gardner et al. (1996) |

| pT-COW-0162 | Apr, tetQ, tet, PG0162 | This study |

| pET102-TOPO | Expression vector, Apr, His tag | Life Science Inc |

| pET0162 | pET102-based PG0162 expressing plasmid | This study |

Bioinformatics analysis

The secondary and tertiary structure prediction and modelling of the protein were performed using the Modeller software package (Eswar et al., 2007) and I-Tasser online software (zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER). The models were validated using the WHATIF program (Vriend, 1990). The amino acids sequence blast was used NCBI online protein blast tools (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Expression of PG0162 in P. gingivalis

The ragA promoter which was reported as a putative strong promoter in P. gingivalis (Nishikawa & Yoshimura, 2001), was amplified by using the primers RagA-P_F (containing BamHI restriction site), and RagA-P_R (Table 2). The coding region of PG0162 was PCR amplified by using the primers PG0162-Rag_F, and PG0162-Rag_R containing a BamHI restriction site. The amplified PG0162 was then fused to the ragA promoter by PCR using the RagA-P_F and PG0162-Rag_R as primers. The fused fragment was digested by BamHI, and ligated to the BamHI digested pT-COW plasmid (Gardner et al., 1996). The recombinant plasmid (pT-COW-0162) was recovered from E. coli DH5α, and then used to electroporate P. gingivalis W83 by using Bio-Rad the electroporation instrument at 2.5 V and resistance of 800 Ω (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Isogenic strains of P. gingivalis carrying the pT-COW-0162 recombined plasmid were selected on BHI agar containing tetracycline.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Overexpress of PG0162 | |

| Rag-A-P_F | TCGGATCCTTGCAGAAATTTCTGCATTTGTGGT |

| Rag-A-P_R | CAGTCAGCTTGTGGAAACTGCTCATAGACTTTTCTTTTGCGTTAAACTT |

| PG0162-rag_F | ATGAGCAGTTTCCACAAGCTGACTGA |

| PG0162-rag_R | TCGGATCCCTAAGCCGACATGCCCATCA |

| Overexpression of PG0162 in E. coli | |

| PG0162_ET_F | CACCATGAGCAGTTTCCACAAGCT |

| PG0162_ET_R | AGCCGACATGCCCATCATTTTGC |

| For In vitro transcription | |

| PG0162_pro_F | GATAAGCAGTTGCTTCTGTTTGT |

| PG0162_pro_R | CTGTATAAAGGCTGACCAATTCAT |

| For EMSA | |

| PG0162_EMSA_F | GCGTTGAGCACCGAGTACGTTTA |

| PG0162_EMSA_R | GAAACTGCTCATAGGAGAATCCTCTTT |

| PG0521_EMSA_F | CCTGCCATTCTGACAGCGAATA |

| PG0521_EMSA_R | GCTTGGTTTGTTATTGTTAGTTGATTGT |

| PG1167_EMSA_F | GATAGAAGTAAGGATTCCCCCCT |

| PG1167_EMSA_R | GAAAAGCGGAACGAAAGGGTCGT |

| PG0985_EMSA_F | GCTCTTGCTTCTTGTTGAAGTTAA |

| PG0985_EMSA_R | CCCCTGTATATATGAAGATGCAAAA |

| PG1660_EMSA_F | GTATCGTTGGTTACCCTCTTCAAGA |

| PG1660_EMSA_R | GGTTACACGGACATACCACCTG |

| PG1661_EMSA_F | GGTGAGATCTTTCGTCAAACTTA |

| PG1661_EMSA_R | TCTGCAAGACTAAGGCTGAAAAA |

| Real-time Quantitative PCR | |

| PG0985_Realtime_F | CGAGGAGGCTGAGGATGCCA |

| PG0985_Realtime_R | GCCTTTCGGATCAGGTTCAGGCA |

| PG1660_Realtime_F | CGAAGATCTCGAACCGTCCGGA |

| PG1660_Realtime_R | GTGCGAAGTCGGTGGAGCTTGA |

| PG1828_Realtime_F | GACTGCCAATCGGGATGATGCA |

| PG1828_Realtime_R | GGATCGATAACCGTTTGTGAGCGA |

| PG1317_Realtime_F | GCCTTCGGTAGCATTGTGGCCTA |

| PG1317_Realtime_R | GTGTCCTCGCTCCATCTGGTGT |

| PG1221_Realtime_F | GCAACTGGACGAAACGAAAGAGCT |

| PG1221_Realtime_R | CCTCTTGTTGCTGCTACCGAACT |

| PG1545_Realtime_F | CACGGTAAGCACCTGAAGACCT |

| PG1545_Realtime_R | GGACGGAACTGAGTGAAATAGAGAT |

| PG0245_Realtime_F | CATGCTGGACGAAGGAGACTTCT |

| PG0245_Realtime_R | CATTCGTCGTGCCATACTCGGAT |

| 16S_Realtime_F | CGAGAGCCTGAACCAGCCAAGT |

| 16S_Realtime_R | GATAACGCTCGCATCCTCCGTATTA |

| PG0162_realtime_F | CCACAAGCTGACTGATGATGAAT |

| PG0162_realtime_R | GAAGCGTATGGATCACCTTGATA |

| For RACE | |

| Outer primer | GCTGATGGCGATGAATGAACACTG |

| PG0162_prom_R | GAAACTGCTCATAGGAGAATCCTCTTT |

Note: BamHI enzyme recognition sequence was underlined in primers.

Overexpression and purification of the recombinant PG0162 (rPG0162) protein

The PG0162 coding region was amplified by PCR and then ligated to an expression vector pET102/D-TOPO (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA). The primers used as listed in Table 2. The recombinant plasmid designated pET0162, was then transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA). Overexpression of pET0162 was induced by 1 mM of isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16 °C. The recombinant protein (rPG0162) carrying a His6 tag at the C-terminal was purified from E. coli cell lysate using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) beads (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot

SDS-PAGE of both the induced and purified rPG0162 was analyzed as previously reported (Olango et al., 2003). The separated proteins were transferred to Bio-Trace nitrocellulose membrane (Pall Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI) using a Semi-Dry Trans-blot apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 15 V for 30 min. The blots were probed with primary antibody against the His-tag (mouse; 1:1000 dilution), and the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse; 1:1000 dilution) was horseradish peroxidase conjugated (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). Immunoreactive proteins were detected using the Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus Kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA).

In vitro Transcription

In vitro transcription assays were performed using the E. coli RNA Polymerase Core enzyme (Epicentre, Madison, WI) and the purified rPG0162 protein. The DNA fragment containing the promoter region of the PG0162 gene was used as a template. The reaction mix which contained 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM DTT, 0.01% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM each of NTP mix, ∼1 mCi [α-32P]-ATP (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) was incubated at 37 °C for 2 hr. Samples were analyzed on a denaturing urea polyacrylamide gel and quantified using the phosphor imaging system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

RNA isolation and cDNA systhesis

For RNA isolation, the cells were grown to OD600 of 0.8∼1.0 and collected by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. Total RNA was isolated from P. gingivalis culture using the SV Total RNA Isolation kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by using the High Fidelity cDNA synthesis kit according to manufacturer’s protocol (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

RNA Ligase Mediated Rapid Amplification of cDNA End (5’ RLM-RACE) assay

The transcription start site (TSS) of PG0162 was determined by 5’-RACE using the First Choice RLM-RACE kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Primers used for the nested PCR are listed in Table 2. The PCR fragment was ligated to the pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA) then transformed into E. coli Top10 competent cells. The inserts were confirmed by PCR and sequencing using the M13 reverse primer (Eton Bioscience, San Diego, CA).

DNA microarray

DNA microarray gene expression analyses were performed using the Roche NimbleGen customer arrays (100910_CW_P_ging_w83_expr_HX12) according to the standard NimbleGen procedure (NimbleGen Arrays User’s Guide: Gene Expression Analysis v5.1) as previous reported previously (Dou et al., 2014) .

Real-time quantitative PCR

The primers for real-time PCR assay were listed in Table 2. Amplification was performed with the SYBR Green kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and real-time fluorescence was detected using the Cepheid Smart Cycler real-time PCR apparatus (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). PCR amplifications were performed as follows: 95 °C for 15 min; 94 °C for 15 sec, 54 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 30 sec; 40 cycles. Each measurement was performed in triplicate. The 16S rDNA was used as an internal control to normalize the variation due to differences in reverse transcription efficiency, and the ΔΔCT method was used to analyze the data as described elsewhere (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

DNA fragments carrying the promoter region of the candidate genes were PCR amplified from P. gingivalis W83 genomic DNA and then labeled with biotin using the Biotin 3’ end DNA labeling kit (Thermo Scientific/Pierce Bio, Rockfold, IL). The EMSA was performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Thermo Scientific/Pierce Bio, Rockfold, IL). In brief, 0.5, 1, 2 or 5 pmol of the purified rPG0162 was mixed with 10 fmol of biotin-labeled DNA and binding buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT; pH7.5), incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The samples were resolved in 5% of polyacrylamide non-denaturing gel and analyzed using the Chemiluminescence nucleic acid detection kit (Thermo Scientific/Pierce Bio, Rockfold, IL).

PG0162 target promoter motif prediction

The promoter region of genes up- or downregulated were analyzed by using the online promoter prediction software (fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html), the online Scope software (genie.dartmouth.edu/scope), and the sequence logo was generated using the online Weblogo (weblogo.berkeley.edu) software.

Results

PG0162 encodes for a DNA binding protein

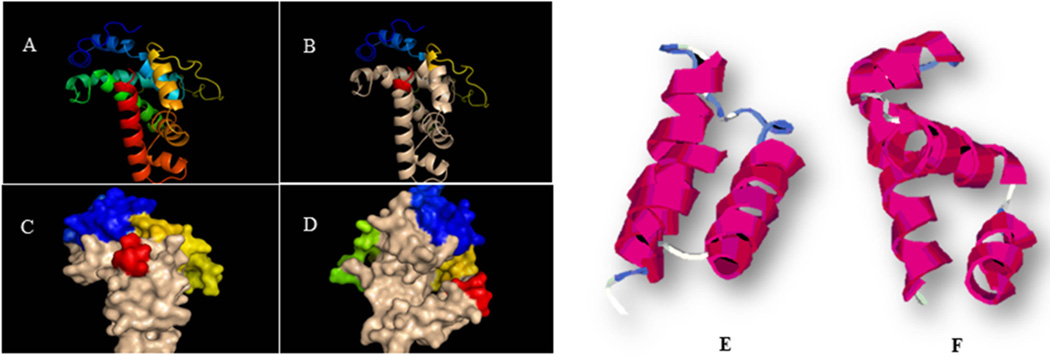

PG0162 is 582 bp in length and is predicted to code for a 193 amino acids protein annotated as an ECF sigma factor, or sigma 24 (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome). Protein modeling shows that the PG0162 protein has sigma 70 subdomains at the amino acid positions 35–93 and 132–187 respectively (Fig. 1B). The subdomain at position 35–93 represents sigma factor subdomain-2, in contrast to subdomain-4 identified at amino acid position 132–187. Subdomain-4 carries a helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain, while subdomain-2 contains three helical domains (Fig. 1E, F).

Fig. 1.

The secondary and tertiary structure prediction of PG0162. (A) Model of PG0162. Blue – N terminal end loop and helix, Red – C terminal end helix, Sky Blue and Green – most conserved sigma −70 domain 2, Brown & orange - sigma −70 promoter interacting SR-4 domain. (B) Sigma 70 domain identified in PG0162 (Position 35–93; 132–187, tan color). (C) Surface model of PG0162. (D) Surface model of PG0162, 90° rotation. (E) Secondary structure of sigma 70 subdomain-2. (F) Secondary structure of sigma 70 subdomain-4.

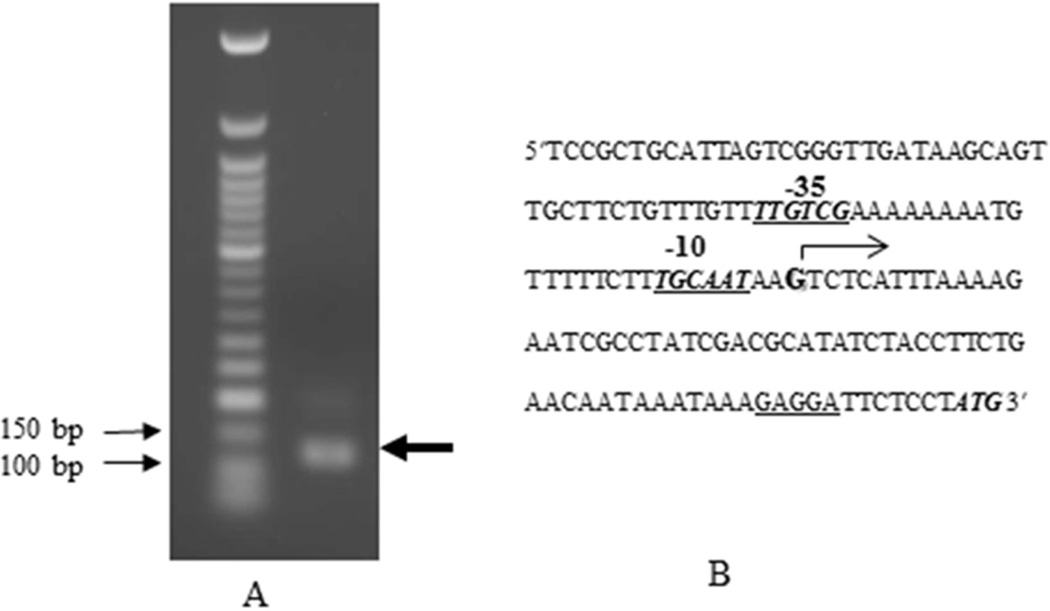

Transcription start site mapping of PG0162 gene

The TSS of PG0162 was determined using RLM-RACE. As shown in Fig. 2(A), a 120-bp-length DNA fragment was PCR amplified. A guanine (G) residue 69-nt upstream of the annotated translation start codon (ATG) was identified as the TSS by nucleotide sequencing (Fig. 2B). Sequences predicted to represent −35 element (5’-TTGTCG-3’), −10 element (5'-TGCAAT-3') and ribosome binding site (5'-GAGGA-3') were observed upstream of the predicted translation start codon (ATG) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

5′ RLM-RACE showed that the transcription of PG0162 start from a guanine which is located 69 nt upstream of the translation start codon. (A) PCR amplification of PG0162 promoter region was showed about 120 bp. (B) Promoter region of PG0162. The transcription start site G is bold shadowed; the translation start codon ATG is bold italic; the −35 and −10 elements were bolded, italic and underlined; the ribosome binding site GAGGA was underlined.

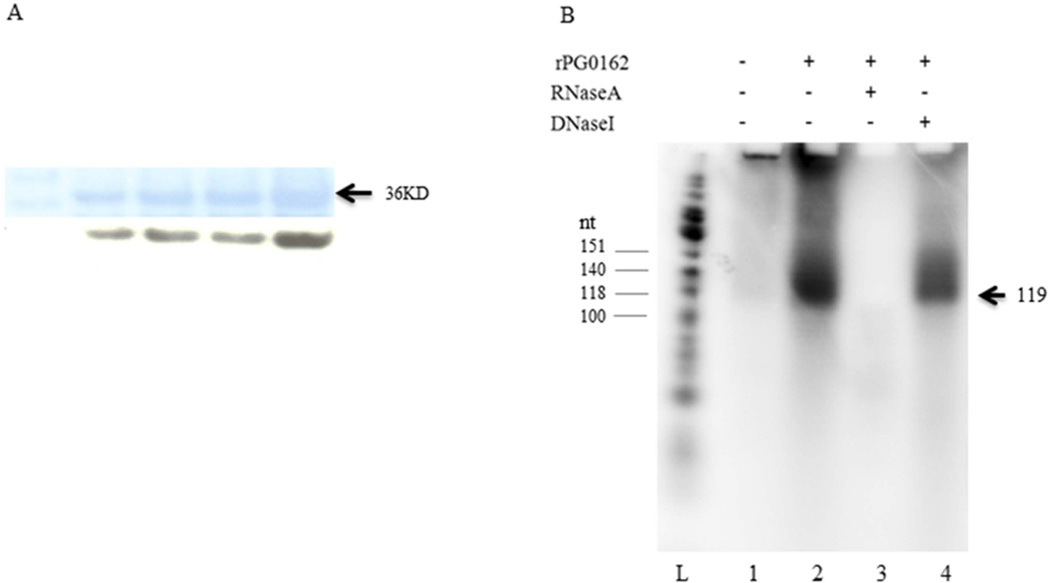

In vitro transcription of PG0162

Many ECF sigma factors are able to recognize their own promoter resulting in autoregulation of their own gene expression (Huang et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2012). To test if rPG0162 can start its own gene transcription, a 175-base-pair (−56 to +119) DNA fragment carrying the promoter region of the PG0162 gene was used as a template in in vitro run-off transcription reconstitution assays (Fig. 3A). The rPG0162 protein was purified from E. coli and confirmed by using anti-His tag antibody in western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). Because the PG0162 gene is transcribed from the guanine 69 nucleotides upstream of translation start codon ATG, the length of RNA product is predicted to be 119 nucleotides. As shown in Fig. 3(B) with the E. coli core RNAP, rPG0162 could activate the PG0162 promoter in vitro, resulting in a significant transcript (∼119 nt) (lanes 2 and 4, Fig. 3B). In the control experiment when the rPG0162 protein was omitted or in the presence of RNaseA, there were no transcription products generated (lanes 1 and 3, Fig. 3B), indicating that P. gingivalis PG0162 ECF sigma factor is autoregulated and could initiate transcription from its own promoter. Hence, our results infer two mechanisms by which PG0162 could operate, either through PG0162 protein initiating transcription of a set of genes (or) directly at the transcription level through autoregulation. However, the specific conditions when these two mechanisms operate are yet to be explored.

Fig. 3.

In vitro transcription analysis of PG0162. (A) Western blot of rPG0162. (B) In vitro transcription product analysis. L: φX174 DNA/HinfI Dephosphorylated Marker; Lane 1: no rPG0162; Lane 2: with rPG0162; Lane 3: RNaseA was added; Lane 4: DNaseI was added.

Creation of in vivo PG0162 overexpression strain P. gingivalis FLL391

The sensitivity of the PG0162-deficient mutant of P. gingivalis to several environmental signals including hydrogen peroxide, oxygen, NaCl, alcohol, low and high pH, were similar to the wild-type (data not shown). Overexpression of ECF sigma factor usually results in the expression of the sigma factor-dependent genes in the absence of the inducing signal (Llamas et al., 2008; Beare et al., 2003; Llamas et al., 2006). Since an appropriate PG0162 inducing environmental signal is unknown, an isogenic strain overexpressing the PG0162 gene was created. The PG0162 encoding region was fused to the ragA promoter and then ligated to pT-COW as described above. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into the P. gingivalis wild-type strain by electroporation and the chimera strains were selected on BHI agar plates with 0.3 µg/ml of tetracycline. Plasmid DNA from randomly chosen tetracycline resistant P. gingivalis colonies were subjected to PCR and sequencing analyses for confirmation of the correct construct. One of the PG0162 overexpression isogenic strain designated P. gingivalis FLL391 was randomly chosen and used for further studies (Table 1). Using quantitative real-time PCR the expression level of the PG0162 gene was increased 1.89 ± 0.77 fold in FLL391 compared to the wild-type strain.

Genes regulated by the P. gingivalis PG0162 ECF sigma factor

To identify the genes that might be regulated by the sigma factor PG0162, total RNA from P. gingivalis FLL391 cells was isolated and subjected to cDNA microarray analysis. The fold change of gene expression was cutoff of 1.5. As listed in Table 3 and Supplemental Table 1 and 2, approximately 260 genes including 88 genes encoding hypothetical proteins were upregulated more than 1.5 fold in P. gingivalis FLL391; In contrast, 286 genes including 97 genes of unknown function were downregulated more than 1.5 fold in FLL391 compared to the wild-type strain (Table 3; Supplemental Table 1&2).

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes in FLL391

| Gene Code | Annotation | Fold-change (FLL391 vs W83) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulator, TCS | |||

| Upregulated | |||

| PG0142 | SpoOJ regulator protein | 1.5 | 0.000382808 |

| PG0396 | Crp/FNR family transcriptional regulator | 1.5 | 1.51E-10 |

| PG0543 | transcriptional regulator, putative | 2.0 | 5.65E-07 |

| PG0594 | RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor | 1.8 | 6.82E-14 |

| PG0985 | ECF subfamily RNA polymerase sigma factor | 5.4 | 1.14E-16 |

| PG1432 | sensor histidine kinase | 1.8 | 1.97E-06 |

| PG1501 | TetR family transcriptional regulator | 1.9 | 6.68E-09 |

| PG1660 | ECF subfamily RNA polymerase sigma factor | 2.4 | 0.147397 |

| Downregulated | |||

| PG0997 | transcriptional regulator, putative | −2.0 | 3.43E-10 |

| Transporter | |||

| Upregulated | |||

| PG0065 | RND family efflux transporter MFP subunit | 1.5 | 2.14E-08 |

| PG0192 | cationic outer membrane protein OmpH | 1.9 | 3.14E-08 |

| PG0193 | cationic outer membrane protein OmpH | 1.8 | 2.86E-08 |

| PG0321 | arginine/ornithine transport system ATPase | 2.0 | 7.36E-16 |

| PG0322 | serine/threonine transporter | 1.5 | 2.35E-13 |

| PG0381 | potassium/proton antiporter | 1.5 | 9.39E-05 |

| PG0436 | capsular polysaccharide transport protein, putative | 1.7 | 1.06E-12 |

| PG0437 | BexD/CtrA/VexA family polysaccharide export protein | 2.1 | 8.98E-15 |

| PG0538 | outer membrane efflux protein | 1.8 | 6.20E-14 |

| PG0539 | RND family efflux transporter MFP subunit | 1.5 | 2.08E-11 |

| PG0762 | trigger factor, putative | 1.9 | 7.24E-07 |

| PG0782 | MotA/TolQ/ExbB proton channel family protein | 1.6 | 9.94E-07 |

| PG1446 | MATE efflux family protein | 1.5 | 0.0224061 |

| PG1663 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 4.9 | 9.52E-17 |

| PG1664 | ABC transporter, permease protein, putative | 3.7 | 1.13E-12 |

| PG1665 | ABC transporter, permease protein, putative | 2.7 | 1.40E-13 |

| PG1666 | RND family efflux transporter MFP subunit | 3.0 | 2.08E-19 |

| PG1667 | outer membrane efflux protein | 2.4 | 1.54E-18 |

| Downregulated | |||

| PG0462 | transporter, putative | −1.7 | 2.40E-15 |

| PG0646 | iron compound ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | −2.2 | 2.56E-09 |

| PG0647 | iron compound ABC transporter, permease protein | −1.7 | 7.85E-11 |

| PG0671 | iron compound ABC transporter, permease protein | −1.7 | 6.29E-10 |

| PG0683 | ABC transporter, permease protein, putative | −1.6 | 3.66E-05 |

| PG0684 | ABC transporter, permease protein, putative | −1.8 | 8.01E-07 |

| PG0685 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | −1.9 | 7.45E-11 |

| PG1043 | ferrous iron transport protein B | −1.6 | 3.45E-05 |

| PG1173 | YkgG family protein | −1.7 | 1.47E-05 |

| PG1225 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | −1.6 | 4.85E-09 |

| PG1760 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | −1.6 | 6.10E-13 |

| PG1792 | sodium/hydrogen antiporter | −2.2 | 1.26E-24 |

| PG1946 | ABC 3 transporter family protein | −1.6 | 4.53E-10 |

| PG2218 | potassium transporter peripheral membrane component | −1.8 | 6.77E-07 |

| PG2219 | potassium uptake protein TrkH | −1.6 | 6.60E-08 |

| stress related protein | |||

| Upregulated | |||

| PG0045 | heat shock protein 90 | 1.8 | 0.00241996 |

| PG0090 | Dps family protein | 2.2 | 9.43547E-08 |

| PG0165 | heat shock protein 15 | 2.3 | 5.37866E-13 |

| PG0521 | co-chaperonin GroES | 2.3 | 1.38821E-05 |

| PG1208 | molecular chaperone DnaK | 1.7 | 0.00125706 |

| Downregulated | |||

| PG0034 | thioredoxin | −1.7 | 2.65088E-06 |

| PG0245 | universal stress protein | −2.7 | 6.34711E-18 |

| PG0674 | indolepyruvate oxidoreductase subunit B | −1.8 | 1.85595E-09 |

| PG0675 | indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, alpha subunit | −1.7 | 1.94856E-12 |

| PG1058 | OmpA family protein | −1.6 | 3.17886E-15 |

| PG1221 | short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family oxidoreductase | −2.1 | 4.91002E-11 |

| PG1545 | superoxide dismutase, Fe-Mn | −2.7 | 0.000957244 |

| PG2069 | short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family oxidoreductase | −1.6 | 9.94896E-16 |

Two ECF sigma factor encoding genes (PG0985 and PG1660) were upregulated 5.4 and 2.3 fold respectively in FLL391 (Table 3). There were several genes (PG0142, PG0396, PG0543, and PG1501) that encoded transcriptional regulator that were also upregulated (Table 3). Only 5 stress related genes were upregulated. Taken together, these results indicate that the differentially expressed genes in FLL391 might be regulated by PG0162 through a complex regulatory network.

Confirmation of the DNA microarray data by real-time quantitative PCR

To confirm the DNA microarray data, seven of the most highly modulated genes (PG0245, PG0985, PG1221, PG1317, PG1545, PG1660, and PG1828) were selected to further study their expression profile in strain FLL391. Using specific oligonucleotide primers in real-time PCR analysis, the PG0245, PG1221, and PG1545 genes were downregulated more than 2 fold, in contrast to PG0985, PG1317, PG1660, and PG1828 which were all upregulated more than 2 fold in FLL391 compared to the wild-type strain (Table 4).

Table 4.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of differentially expressed genes in FLL391

| Gene | Annotation | Fold-change (FLL391/W83) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR | DNA microarray | ||

| PG0245 | universal stress protein | −5.08±0.02 | −2.73 |

| PG0985 | ECF subfamily RNA polymerase sigma factor | 15.05±0.88 | 5.4 |

| PG1221 | short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family oxidoreductase | −2.55±0.14 | −2.11 |

| PG1317 | hypothetical protein PG1317 | 2.84±0.38 | 2.09 |

| PG1545 (sodB) | superoxide dismutase, Fe-Mn | −3.53±0.07 | −2.71 |

| PG1660 | ECF subfamily RNA polymerase sigma factor | 18.72±1.63 | 2.35 |

| PG1828 | putative lipoprotein | 3.07±0.23 | 2.34 |

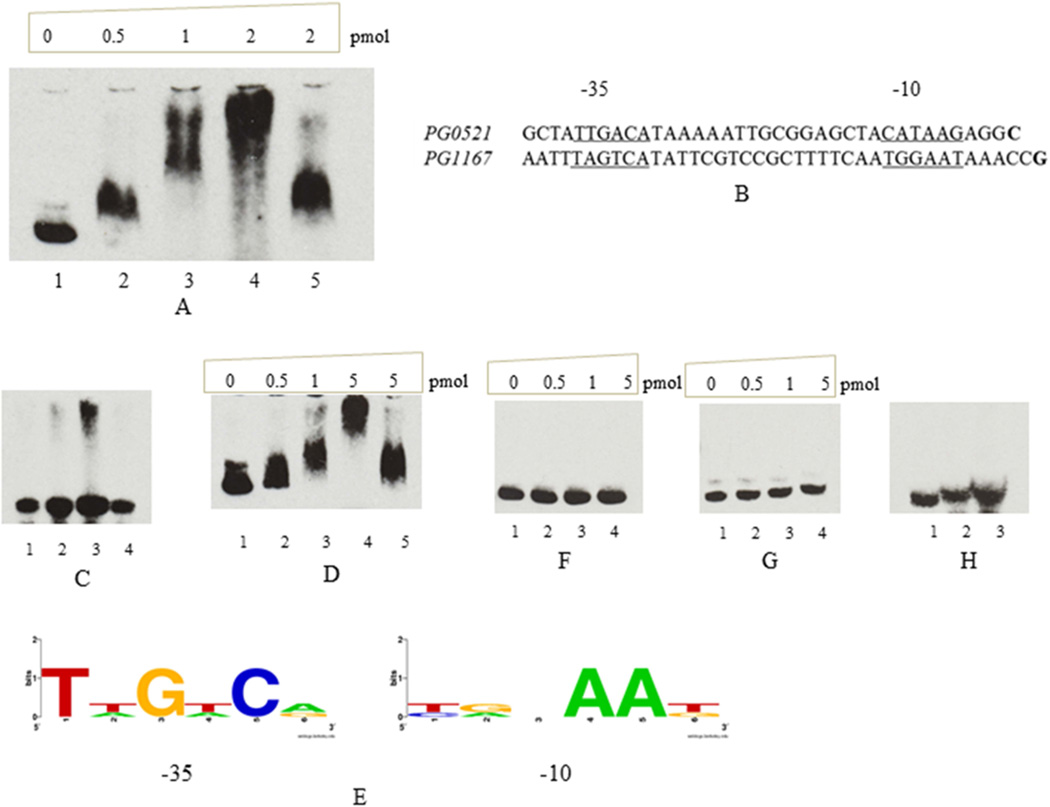

rPG0162 binding to promoter region of PG0162

Most ECF sigma factors were known to autoregulate their own expression (Helmann, 2002; Mascher, 2013). We have used EMSA, a gel mobility shift assay, in order to determine the protein-DNA interaction. The purified rPG0162 was used in this assay to determine its ability to bind to the promoter region of PG0162. A 0.26 kb DNA fragment spanning from 188 bp upstream to 80 bp downstream of the TSS and including the putative −35 and −10 elements of the PG0162 promoter region was PCR amplified, purified, and biotin labelled. In Fig. 4(A), the EMSA results showed that the retardation of the 0.26 kb fragment carrying the PG0162 promoter region was concentration dependent in the presence of the rPG0162 protein.

Fig. 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showed that rPG0162 could bind to the 10 fmol of promoter of PG0162, PG0521, and PG1167. (A) rPG0162 bind to PG0162 promoter. Lane 1, no protein; Lane 2, 0.5 pmol of rPG0162; Lane 3, 1 pmol of rPG0162; Lane 4, 2 pmol of rPG0162; Lane 5, 2 pmol of rPG0162 plus unlabeled PG0162. (B) Promoter regions of PG0521 and PG1167, the −35 and −10 elements were underlined; the putative transcription start site were bolded. (C) rPG0162 could bind to promoter of PG0521. Lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 0.5 pmol of rPG0162; lane 3, 1 pmol of rPG0162; lane 4, 1 pmol of rPG0162 and non-labeled PG0521. (D) rPG0162 could bind to promoter of PG1167. Lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 0.5 pmol of rPG0162; lane 3, 1 pmol of rPG0162; lane 4, 5 pmol of rPG0162; lane 5, 5 pmol of rPG0162 and non-labeled PG1167 promoter DNA. (E) Logo of −35 and −10 consensus motifs recognized by PG0162. (F) rPG0162 did not bind to promoter of PG0985. (G) rPG0162 did not bind to promoter of PG1660. F and G: Lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 0.5 pmol of rPG0162; lane 3, 1 pmol of rPG0162; lane 4, 5 pmol of rPG0162. (H) rPG0162 did not bind to promoter of PG1661. Lane 1, no protein; lane 2, 0.5 pmol of rPG0162; lane 3, 1 pmol of rPG0162.

PG0162 may regulate PG0521 (groES) and PG1167

The PG0521 (groES), and PG1167 was upregulated 2.3 and 2.5 fold respectively in P. gingivalis FLL391. In silico analysis of the promoter region of PG0521 reveal sequences representing the −35 (5′-TTGACA-3′) and −10 (5′-CATAAG-3′) elements. Similarly, the “-35” and “-10” element sequences of PG1167 are represented by “5′-TAGTCA-3′”, and “5′-TGGAAT-3′” respectively (Fig. 4B). The 140-bp promoter region of PG0521 and 182-bp promoter region of PG1167 were PCR amplified and labelled by Biotin. The EMSA results showed that rPG0162 could bind to the promoter regions of these two genes resulting in significant retardation compared to the negative control (Fig. 4C, D). Collectively, the consensus promoter motif analysis showed that PG0162 may recognize −35 (TT(A)GA(T)Cn) and −10 (T(C)A(G)nAAT(G)) consensus elements of the regulated genes (Fig. 4E).

PG0985 and PG1660, two other ECF sigma factors, were also upregulated more than 2 fold in P. gingivalis FLL391 (Table 3). In addition, a gene cluster from PG1662 to PG1665 which also appears to part of the same transcriptional unit was upregulated in FLL391 (Table 3). To evaluate whether PG0162 was involved in regulation of these genes, their promoter regions were PCR amplified, purified and biotin labelled. The EMSA results showed that rPG0162 could not bind to any of these three promoters (Fig. 4F, G, H). Taken together, it is likely that some genes upregulated in P. gingivalis FLL391 are not directly regulated by PG0162 via binding to its promoter region.

Discussion

ECF sigma factors have been recognized and belong to one of the largest and most diverse class of regulators to facilitate signal transduction in response to environmental cues in bacteria (Kazmierczak et al., 2005). This response implies that environmental signals can modulate the expression of specific genes and hence contribute to microbial pathogenesis. Several reports have documented the role of ECF sigma factors in the pathogenic process including RpoE in Haemophilus influenzae, Vibrio cholerae, V. harveyi, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Craig et al., 2002; Kovacikova & Skorupski, 2002; Osborne & Coombes, 2009; Rattanama et al., 2012); SigmaE, SigmaC, SigmaH, and SigmaL in M. tuberculosis (Hahn et al., 2005; Manganelli et al., 2001; Mehra et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2004); AlgU, PvdS, Pum3, and FpvI in P. aeruginosa (Llamas et al., 2009; Potvin et al., 2008); ECF sigma factors in P. syringae (Thakur et al., 2013), and HrpL in Erwinia amylovora (Wei & Beer, 1995). The unique PG0162 in P. gingivalis is annotated as an ECF sigma factor with conserved sigma factor 70 subdomains. Its impact on the pathogenic process in P. gingivalis is implied by its ability to cause the reduction of gingipain, hemagglutination and hemolytic activities in the PG0162-deficient mutant, FLL350 (Dou et al., 2010). Furthermore, with the ability of PG0162 to regulate whether directly or indirectly, the expression of the sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase genes in P. gingivalis FLL391 supports the hypothesis of its involvement in the virulence of P. gingivalis. The sialidase and O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase in P. gingivalis are important to the maturation of gingipains, and infection in an animal model (Aruni et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012).

In this study, the PG0162 ECF sigma factor function(s) including its autoregulation was confirmed by its ability to interact with the RNA core polymerase from E. coli, the binding and initiation of transcription from its promoter. Other genes (PG0521 and PG1167) that were highly upregulated in the isogenic strain overexpressing the PG0162 gene showed a similar transcription initiation profile. The interrogation of the promoter regions from the PG0162, PG0521 and PG1167 genes revealed a −35 and −10 consensus motif sequence. The −35 promoter element recognized by PG0162 is different from the traditionally −35 element (TTGACA) in gram-negative bacteria (Harley & Reynolds, 1987; Shimada et al., 2014) and the consensus promoter motif recognized by the P. gingivalis PG1827 ECF sigma factor previously reported (Yanamandra et al., 2012).

Usually the alternative sigma factors are regulated at the transcriptional, translational, and/or post-translational levels. In most cases, the ECF sigma factor is regulated by its cognate anti-sigma factor protein, which is encoded by a downstream gene on the same transcriptional unit. Bioinformatics analyses have shown that because PG0162 is on a single gene transcriptional unit and is missing any downstream putative anti-sigma factor component would support the hypothesis that PG0162 is an orphan sigma factor. Currently, it is unknown whether an anti-sigma factor protein could regulate PG0162, or other transduction mechanisms including a two-component system(s). Secondary structure predictions showed that the P. gingivalis ECF sigma factor PG0162 and PG1660 have similar subdomains which could indicate that these two sigma factors may share some function relatedness. Because PG1660 was upregulated in the P. gingivalis FLL391 isogenic strain, we cannot yet rule out the likelihood that the PG1660 cognate anti-sigma factor protein could also regulate PG0162. This is under further investigation in laboratory.

An isogenic mutant strain of P. gingivalis defective of PG0162 did not show any sensitivity to multiple environmental stress signals including temperature, pH, oxidative stress and metal ions. This could suggest that the ECF sigma factor PG0162 may not be adapted to the transduction of these signals. Because overexpression of ECF sigma factors usually results in the expression of the sigma-dependent genes in the absence of the inducing signal (Beare et al., 2003; Llamas et al., 2006; Llamas et al., 2008), our study of the transcription profile P. gingivalis FLL391 have indicated multiple genes that could be directly or indirectly regulated by PG0162. While several virulence related genes were modulated, other genes involved in transport were upregulated. For example, the upregulation of the ABC transporter system from PG1662 to PG1667 downstream of ECF sigma factor PG1660 gene in FLL391 was consistent to the assumption that PG0162 function could affect specific transportation system(s) that is vital for its environmental adaptation. Several of the pathways most highly upregulated involve ppGpp and selenocysteine biosynthesis and autoinducer biosynthesis through homocysteine synthesis (Table 5). Together, the resultant components of these pathways are vital to reestablish homeostasis following environmental stress.

Table 5.

Highly modulated pathways in FLL391

| Highly downregulated | Highly upregulated | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carbohydrate biosynthesis | Transfer RNA charging pathways |

| 2 | GDP mannose production | Serine biosynthesis |

| 3 | Cysteine tRNA synthesis | Chorismate pathway, serine and tryptophan synthesis |

| 4 | Aerobic respiration | Cell structure synthesis |

| 5 | Fatty acid beta oxidation | ppGpp biosynthesis |

| 6 | Protein degradation | Glutamate degradation |

| 7 | Nitrate reduction dissimilatory pathway | Ammonia oxidation |

| 8 | Glycogen degradation | Selenocysteine biosynthesis |

| 9 | Aromatic compound biosynthesis | Coenzyme A biosynthesis |

| 10 | Tryptophan biosynthesis | Autoinducer biosynthesis through homocysteine synthesis |

Other ECF sigma factors and transcriptional regulators were upregulated in P. gingivalis FLL391 thus indicating that the PG0162 ECF sigma factor could be part of a complex regulatory signaling network in P. gingivalis. Crosstalks among bacterial regulatory networks have been shown to have important physiological consequences that is vital for microbial survival/pathogenesis (Gupta et al., 2014; Coggan & Wolfgang, 2012). While it is not yet confirmed we cannot rule out the likelihood of crosstalk between the PG0162 ECF sigma factor and the different regulatory networks.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the sigma factor function properties of PG0162 in P. gingivalis. It is likely that PG0162 may be involved in a unique and complex regulatory network in response an environmental signal(s) that needs to be clarified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Public Health Services Grants R56DE13664, DE019730, DE019730 04S1, DE022508, DE022724 from NIDCR (to H.M.F).

Reference

- Aruni W, Vanterpool E, Osbourne D, Roy F, Muthiah A, Dou Y, Fletcher HM. Sialidase and sialoglycoproteases can modulate virulence in Porphyromonas gingivalis . Infect. Immun. 2011;79:2779–2791. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00106-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare PA, For RJ, Martin LW, Lamont IL. Siderophore-mediated cell signalling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: divergent pathways regulate virulence factor production and siderophore receptor synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;47:195–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig JE, Nobbs A, High NJ. The extracytoplasmic sigma factor, final sigma(E), is required for intracellular survival of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in J774 macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:708–715. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.708-715.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggan KA, Wolfgang MC. Global regulatory pathways and cross-talk control Pseudomonas aeruginosa environmental lifestyle and virulence phenotype. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2012;14:47–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detert J, Pischon N, Burmester GR, Buttgereit F. The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:218. doi: 10.1186/ar3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Osbourne D, McKenzie R, Fletcher HM. Involvement of extracytoplasmic function sigma factors in virulence regulation in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;312:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Aruni W, Luo T, Roy F, Wang C, Fletcher HM. Involvement of PG2212 a Zinc-finger protein in the regulation of oxidative stress resistance in Porphyromonas gingivalis W83. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:4057–4070. doi: 10.1128/JB.01907-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91:914–920. doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswar N, Webb B, Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen MY, Pieper U, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Protein Sci Chapter 2. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0209s50. Unit 2.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francez-Charlot A, Frunzke J, Reichen C, Ebneter JZ, Gourion B, Vorholt JA. Sigma factor mimicry involved in regulation of general stress response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3467–3472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810291106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RG, Russell JB, Wilson DB, Wang GR, Shoemaker NB. Use of a modified Bacteroides Prevotella shuttle vector to transfer a reconstructed β-1,4-D-endoglucanase gene into Bacteroides uniformis and Prevotella ruminicola B14. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:196–202. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.196-202.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Gupta A, Kumar S, Mishra R, Singh C, Tripathi AK. Cross-talk between cognate and noncognate RpoE sigma factors and Zn2+-binding anti-sigma factors regulates photooxidative stress response in Azospirillum brasilense . Antioxid. Redox Signaling. 2014;20:42–59. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MY, Raman S, Anaya M, Husson RN. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor SigL regulates polyketide synthases and secreted or membrane proteins and is required for virulence. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7062–7071. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.7062-7071.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley CB, Reynolds RP. Analysis of E.coli promoter sequences. Nucl. Acids Res. 1987;15:2343–2361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmann JD. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv Microb Physiol. 2002;46:47–110. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(02)46002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LG, McKenzie RM, Robles A, Fletcher HM. Oxidative stress resistance in Porphyromonas gingivalis . Future Microbiol. 2012;7:497–512. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TD, Ellermeier CD. Extra cytoplasmic function sigma factor activation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Fredrick KL, Helmann JD. Promoter recognition by Bacillus subtilis sigmaW: autoregulation and partial overlap with the sigmaX regulon. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3765–3770. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3765-3770.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba H, Amano A. Roles of oral bacteria in cardiovascular diseases--from molecular mechanisms to clinical cases: Implication of periodontal diseases in development of systemic diseases. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;113:103–109. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09r23fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmierczak MJ, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. Alternative sigma factors and their roles in bacterial virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:527–543. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.4.527-543.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenbrander PE. Oral microbial communities: biofilms, interactions, and genetic systems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:413–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. The alternative sigma factor sigma(E) plays an important role in intestinal survival and virulence in Vibrio cholerae . Infect. Immun. 2002;70:5355–5362. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5355-5362.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le JA, Torelli R, Sanguinetti M, Giard JC, Hartke A, Auffray Y, Benachour A. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factor SigV plays a key role in the original model of lysozyme resistance and virulence of Enterococcus faecalis . PLoS One. 2010;5:e9658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Kurniyati Hu B, Bian J, Sun J, Zhang W, Liu J, Pan Y, Li C. Abrogation of neuraminidase reduces biofilm formation, capsule biosynthesis, and virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis . Infect. Immun. 2012;80:3–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05773-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li J, Wu Z, Pei H, Zhou J, Xiang H. Identification and characterization of the cognate anti-sigma factor and specific promoter elements of a T. tengcongensis ECF sigma factor. PloS One. 2012;7:e40885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas MA, Mooij MJ, Sparrius M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Ratledge C, Bitter W. Characterization of five novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa cell-surface signalling systems. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67:458–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas MA, Sparrius M, Kloet R, Jimenez CR, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C, Bitter W. The heterologous siderophores ferrioxamine B and ferrichrome activate signaling pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:1882–1891. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1882-1891.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas MA, van der SA, Chu BC, Sparrius M, Vogel HJ, Bitter W. A Novel extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor regulates virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000572. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganelli R, Voskuil MI, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor sigmaE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41:423–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascher T. Signaling diversity and evolution of extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013;16:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra S, Golden NA, Stuckey K, Didier PJ, Doyle LA, Russell-Lodrigue KE, Sugimoto C, Hasegawa A, Sivasubramani SK, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis stress response factor SigH is required for bacterial burden as well as immunopathology in primate lungs. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205:1203–1213. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KE, Fleischmann RD, DeBoy RT, Paulsen IT, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, et al. Complete genome sequence of the oral pathogenic Bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis strain W83. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5591–5601. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.18.5591-5601.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K, Yoshimura F. The response regulator FimR is essential for fimbrial production of the oral anaerobe Porphyromonas gingivalis . Anaerobe. 2001;7:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Olango GJ, Roy F, Sheets SM, Young MK, Fletcher HM. Gingipain RgpB is excreted as a proenzyme in the vimA-defective mutant Porphyromonas gingivalis FLL92. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3740–3747. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3740-3747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onozawa S, Onozawa S, Kikuchi Y, Shibayama K, Kokubu E, Nakayama M, Inoue T, Nakano K, et al. Role of extracytoplasmic function sigma factors in biofilm formation of Porphyromonas gingivalis . BMC. Oral Health. 2015;15:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-15-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SE, Coombes BK. RpoE fine tunes expression of a subset of SsrB-regulated virulence factors in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. BMC. Microbiol. 2009;9:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin E, Sanschagrin F, Levesque RC. Sigma factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:38–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattanama P, Thompson JR, Kongkerd N, Srinitiwarawong K, Vuddhakul V, Mekalanos JJ. Sigma E regulators control hemolytic activity and virulence in a shrimp pathogenic Vibrio harveyi . PLoS. One. 2012;7:e32523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw LN, Lindholm C, Prajsnar TK, Miller HK, Brown MC, Golonka E, Stewart GC, Tarkowski A, Potempa J. Identification and characterization of σs, a novel component of the Staphylococcus aureus stress and virulence responses. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Yamazaki Y, Tanaka K, Ishihama A. The whole set of constitutive promoters recognized by RNA polymerase RpoD holoenzyme of Escherichia coli . Plos. One. 2014;9:e90447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R, Converse PJ, Ko C, Tyagi S, Morrison NE, Bishai WR. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor sigC is required for lethality in mice and for the conditional expression of a defined gene set. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:25–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur PB, Vaughn-Diaz VL, Greenwald JW, Gross n D. C. Characterization of five ECF sigma factors in the genome of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a. PLoS. One. 2013;8:e58846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriend G. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graph. 1990;8:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei ZM, Beer SV. HrpL activates Erwinia amylovora hrp gene transcription and is a member of the ECF subfamily of sigma factors. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:6201–6210. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6201-6210.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood LF, Ohman DE. Use of cell wall stress to characterize σ22 (AlgT/U) activation by regulated proteolysis and its regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:183–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanamandra SS, Sarrafee SS, naya-Bergman C, Jones K, Lewis JP. Role of the Porphyromonas gingivalis extracytoplasmic function sigma factor, SigH. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:202–219. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.