Abstract

Introduction

We report a phase I trial of photodynamic therapy (PDT) of carcinoma-insitu (CIS) and microinvasive cancer (MIC) of the central airways with the photosensitizer (PS) 2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH). HPPH has the advantage of minimal general phototoxicity over the commonly used PS porfimer sodium (Photofrin®).

Methods

The objectives of this study were 1) to determine the maximally tolerated light dose at a fixed PS dose and 2) to gain initial insight into the effectiveness of this treatment approach. Seventeen patients with 21 CIS/MIC lesions were treated with HPPH with light dose escalation starting from 75 J/cm2 to 85, 95,125, and 150 J/cm2 respectively. Follow-up bronchoscopy for response assessment was done at one and six months, respectively.

Results

The rate of pathological complete response (CR) was 82.4% (14/17 evaluable lesions; 14 patients) at one-month and 72.7% (8/11 lesions; 8 patients) at 6 months. Only 4 patients developed mild skin erythema. One of the three patients in 150 J/cm2 light dose group experienced a serious adverse event. This patient had respiratory distress due to mucus plugging, which precipitated cardiac ischemia. Two additional patients treated subsequently at this light dose had no adverse events. The third sixth patient in this dose group was not recruited and the study was terminated because of delays in HPPH supply. However, given the observed serious adverse event, it is recommended that the light dose not exceed 125J/cm2.

Conclusions

PDT with HPPH can be safely used for the treatment of CIS/MIC of the airways, with potential effectiveness comparable to that reported for porfimer sodium in earlier studies.

Keywords: lung cancer, photodynamic therapy, carcinoma in situ, bronchoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality with a low five-year survival of approximately 15%. Such poor outcomes are attributed to the largely advanced stages at detection. Considerable effort to develop screening strategies for lung cancer in its early, treatable stages is ongoing1. Detection of early stage central carcinoma-in-situ (CIS) and microinvasive carcinoma (MIC) is important, as these are treatable with excellent prognosis. CIS/MIC is identified by bronchoscopic examination of the proximal central airways frequently enhanced by techniques like autofluorescence bronchoscopy and narrow band imaging. Surgical resection, external beam radiation and bronchoscopic ablative techniques can be used to treat CIS/MIC. Superficial airway cancers treated by formal surgical resection may result in significant loss of lung function from their usual central location and frequent multicentricity. A substantial proportion of these patients also have significant cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities, which preclude surgical resection. Therefore advanced bronchoscopic techniques like photodynamic therapy (PDT), electrocautery, argon plasma coagulation (APC), cryotherapy and laser are usually chosen to treat CIS/MIC2.

PDT is light activation of a tumor-localized photosensitizer (PS) to generate cytotoxic reactive oxygen species, predominantly singlet oxygen, to kill tumors3. The photosensitizer porfimer sodium (Photofrin®), has US regulatory approval for the treatment of early and late stage endobronchial cancer, among other indications4–6. Porfimer sodium is the most commonly used PS for treatment of early stage bronchogenic carcinoma and is one of the most extensively studied agents in this setting7–9. While PDT using porfimer sodium for early stage lung cancer is generally considered safe, it is associated with skin phototoxicity, with reported incidence of sunburn ranging from 13–41% when treating CIS/MIC8. Patients’ failure to avoid sunlight and other sources of bright light for 6 weeks contributes to this problem. A number of second-generation PS are effective for early endobronchial disease PDT9–11 but are not available in United States. One such chlorin-based second-generation PS, 2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH), developed at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) has much lower risks of phototoxicity and requires sunlight precautions of only 7–10 days12. HPPH also has deeper tissue penetration because it absorbs light strongly at 665 nm as compared to 630 nm for porfimer sodium. We aimed 1) to study the maximally tolerated light dose at a fixed PS dose and 2) to gain initial insight into the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a single institution, phase 1 dose finding, open label, non-comparative study of HPPH-PDT in patients with bronchogenic CIS, or bronchogenic MIC. The trial (NCI-2010-02114) was carried out at RPCI between August 2004 and April 2013. HPPH was used at a fixed, previously determined systemic dose of 4 mg/m2,7, 13–15. The study followed a conventional 3+3 dose escalation scheme, designed to determine the maximally tolerated light dose (MTD)16. Three patients were evaluated at each light dose cohort. If none of the patients developed a dose-limited toxicity (DLT), the light dose was escalated to the next higher level. DLTs were defined as grade 3 or higher systemic toxicity or grade 3 or higher normal tissue toxicity that was probably or definitely related to PDT. If one of the three patients experienced a DLT, 3 more patients were recruited at that dose level. Further dose escalation proceeded only if none of the three additional patients had any DLT. The protocol indicated that if ≥2 patients in any group had DLT then dose escalation would be stopped. MTD was defined to be the highest PDT light dose, which resulted in no more than 2 instances of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) among 6 patients.

The primary objective of this study was to establish the safety profile of this treatment approach. The secondary objective was to gain some preliminary insight into the treatment response, as determined pathologically by biopsy at 1 month, where possible at 6 months, and by clinical follow-up for adverse events and for continued surveillance per the guidelines of our screening program. Written informed consents were obtained from all patients, and all protocol-related procedures were approved by the RPCI Institutional Review Board and overseen by the RPCI Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Patient selection

At RPCI, a screening program for high-risk patients was initiated in 1998 and has been ongoing17–19. It involves bimodality screening with low dose non-contrast enhanced spiral CT chest and autofluorescence bronchoscopy (AFB) in selected high-risk patients. This high-risk patient population includes patients with previously treated head and neck, lung and aerodigestive tract cancers with no evidence of disease for >1 year. It also included patients with a smoking history of >20 packs/year plus additional risk factors like asbestosis, COPD with a FEV1 <70% of predicted, or first degree relative with lung cancer. Some additional patients had autofluorescence examination of airway while undergoing bronchoscopy for clinically suspicious separate lung lesions. From this cohort, patients with detectable CIS/MIC were recruited for the current study. Patients diagnosed with CIS/MIC at outside institutions were also referred to us for treatment. Patient eligibility criteria included: biopsy confirmed CIS or MIC, defined as lesions radiographically occult and not definable by conventional CT of the chest; age at least 18 years; male or female using medically acceptable birth control; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score 0–2; no contraindications for bronchoscopy; patients with underlying lung disease judged by the treating clinician to be able to withstand mucous/debris at the site of treatment.

Patient exclusion criteria included: porphyria or hypersensitivity to porphyrins or porphyrin-like agents; impaired hepatic alkaline phosphatase or SGOT >3 times the upper normal limits; minimal impairment of renal function (total serum bilirubin >3 mg/dl, serum creatinine > 3 mg/dl); WBC <4000, platelet count <100,000, prothrombin time exceeding 1.5 times the upper normal limit. After one patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) suffered a DLT, evidence of worsening pulmonary symptoms or COPD exacerbation (worsening dyspnea from baseline, fevers, increase amount of sputum or increased purulence/change in color of sputum), that would preclude multiple bronchoscopies, and myocardial infarction or unstable angina in the previous 6 months were added as exclusion criteria.

Ten lung and 3 head and neck cancer patients had prior treatments (Table 1). However, none of the patients had received any chemotherapy or radiation within the 6 months prior to enrollment in this trial. The patients were diagnosed with airway CIS/MIC by our autofluorescence bronchoscopy surveillance or were referred from outside facilities. The Lam classification was used to classify areas seen on bronchoscopic evaluation into class I, II and III under both autofluorescent and white lights20. Briefly, class I indicates normal findings, class II suggests possible abnormality (inflammation on white light exam or slight brownish indistinct area under autofluorescent light) and class III indicates highly suspicious area (thickened, nodular or polypoid area under white light and brown or brownish-red area under autofluorescent light). The patients underwent endobronchial biopsies of abnormal areas (class II or III) under autofluorescence bronchoscopy guidance at RPCI to define the extent of airway abnormality. Repeat biopsies were performed on all referred patients, for internal confirmation of CIS or MIC. The detailed pre-treatment evaluation included history and physical examination, performance status assessment, evaluation of co-morbidities and laboratory studies (baseline electrocardiogram, complete blood count, prothrombin and partial thromboplastin time and serum chemistry). If a recent Chest CT was not available then one was performed to exclude local extension and whole body Positron emission tomogram (PET) scans were performed as needed to exclude local extensions or distal metastases. The radial balloon problem endobronchial ultrasound became available at our facility in 2012 and was used to evaluate the last two patients. Individuals with multi-centric lesions defined as >1 separate lesion per site or at different sites were included in this study.

TABLE 1.

Patient/lesion characteristics

| Patients (N=17)/lesions (N=21) | |

|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 65 (47 – 81) |

| Male/female | 12/5 |

| Race | |

| White | 16 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Lesion type | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma in situ | 20 |

| Invasive squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (lesion under-staged) |

| Lesion location | |

| Trachea | 4 |

| Right main stem bronchus | 3 |

| Left main stem bronchus | 2 |

| Right upper lobe | 1 |

| Left upper lobe | 4 |

| Right middle lobe | 4 |

| Right lower lobe | 2 |

| Right bronchus intermedius | 1 |

| Number of lesions/patient | |

| One lesion | 13 |

| Two lesions | 4 |

| Prior treatment | |

| Surgery | 8 |

| Radiation | 6 |

| Chemotherapy | 6 |

| PDT | 2 |

Photodynamic therapy

HPPH was administered in an outpatient setting by intravenous infusion 44–50 hours before light delivery and vital signs were monitored for 15 min after infusion. Laser light treatment occurred in the Ambulatory Surgery Center under monitored deep sedation or general anesthesia to allow precise delivery of light to the target area. Each lesion was illuminated by a treatment fiber was positioned in the airway adjacent to the index lesion. A tunable dye laser delivered light of 665 ± 3 nm using optical diffuser fibers of 1.0 – 2.5 cm diffuser length. The irradiance was 300 – 400 mW/cm2 and the light dose was escalated starting from 75 J/cm2 to 85, 95, 125 and 150 J/cm2 respectively. The treatment field included the visible lesion and an approximate 5-mm margin around the lesion. Each lesion was treated to the desired light dose level determined in the protocol. Some patients had 2 qualifying lesions that were treated with 2 separate light treatments at the same light dose. Following treatment, patients were monitored in the Ambulatory Center by a physician and hospitalized for two days until they underwent a repeat bronchoscopy for endoscopic removal of post PDT debris and mucus plugs. All patients were instructed to avoid exposure to sunlight or bright indoor light for at least 7 days by wearing protective clothing and sunglasses provided by the RPCI PDT Center. They were also advised to expose small areas of skin to sunlight on Day 8 for 10 minutes to detect any remaining photosensitivity.

Patient follow-up

Whenever possible, patients were evaluated approximately 1 week, 1 month and 6 months after treatment to assess PDT-related toxicities and clinical responses. Biopsies for treatment responses were taken at 1 and 6 month visits. Thereafter, patients were examined at 3–6 months intervals at the discretion of the physician so long as they participated in the lung cancer screening program.

Patient Assessments

Safety

Patients were monitored for systemic toxicity during HPPH administration, laser treatment and each follow-up visit. The occurrence of adverse events (AEs) during the first 30 days post-treatment was recorded using the revised NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0. At each clinic visit, patients were examined for local normal tissue toxicity, performance status, pain level and skin phototoxicity. All AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) were documented as to onset and resolution date, classification of intensity, relationship to treatment, action taken and outcome. AEs and SAEs were recorded as per MedDRA coding (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities).

Response

Since CIS/MIC lesions do not usually cause any significant narrowing of airway lumen, visual assessment of partial responses is unreliable. Therefore, responses were assessed using only pathology of the lesions at follow-up bronchoscopy. Tumor and lesion response to therapy was graded as follows:

Complete response (CR): absence of malignant cells on follow-up endobronchial biopsies.

No response (NR): persistence of CIS/MIC on follow-up endobronchial biopsies.

RESULTS

Details of patient and lesion characteristics are shown in Table 1. Seventeen patients were enrolled. Thirteen patients had one lesion treated, while 4 patients had two distinct lesions treated with the same light dose. All lesions except one were CIS/MIC and none had been treated previously. The lesions were examined under autofluorescent light and white light during bronchoscopy and all lesions were found to be class II or III under both lights. The lesions were predominantly hyperplastic (14/21), few were nodular (6/21) and only one lesion was polypoidal, which is similar distribution to what has been reported previously21, 22. Although autofluorescent light examination helps in determining the extent of the lesion, the lesions tend to be irregular, involving carinas and circumference of the bronchial tree to various degrees, which makes it challenging to determine the exact dimensions by bronchoscopy. We used the laser fiber, which was slightly longer than the dimensions of the lesions to cover the entire abnormal area. Almost all lesions were smaller than 2 cm in length as the length of laser fiber used was 1 cm in 11 lesions, 1.5 cm in 3 lesions, 2 cm in 6 lesions and 2.5 cm in 1 lesion. One lesion in the 150 J/cm2 light dose cohort appeared to have been invasive carcinoma as revealed during subsequent bronchoscopy by radial balloon probe endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) showing cartilage invasion.

Ten patients had experienced prior lung cancer and 3 patients had had prior head and neck cancer; all had received prior treatment. Eight patients had prior surgical resections: 5 had a lobectomy, 1 had two lobectomies and 2 had pneumonectomy. Six patients had received chemotherapy and six had received radiation therapy. Three patients (total three lesions) had CIS/MIC in the field of prior lung radiation, two patients (three lesions) had prior radiation treatment to the contralateral lung and one patient (one lesion) had history of radiation to the head and neck area. Two patients had received prior porfimer sodium PDT to different CIS lesions several months before enrollment in this trial. Four patients had no previous cancer or prior treatment.

All patients had a history of tobacco abuse and most of them had significant comorbidities. Nine patients had known cardiac disease including coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure. Thirteen patients had COPD (6 documented as severe and two on oxygen), and two additional patients had loss of lung function due to prior treatment (two separate lobectomies in one patient and another with lobectomy and radiation therapy). Only one patient had normal pulmonary function tests.

Adverse events

Grade 1 and 2 bronchial secretion retention (mucous plugs), an expected side effect in bronchial PDT and removed by planned bronchoscopy, occurred in 12 patients distributed over all light dose cohorts Grade 1 and 2 pain or cough occurred rarely. Four patients experienced grade 1 erythema and 1 patient experienced slight photophobia. Likely unrelated events included a patient developing myocardial infarction two months after treatment and another patient with history of stroke, atrial fibrillation and polycythemia vera having a cerebrovascular accident one months after treatment. This was attributed to significant underlying risk factors and hypercoagulable state.

The only possibly PDT related serious adverse event (SAE) and DLT, a myocardial infarction and pneumothorax, occurred in the highest light dose cohort (150 J/cm2) in a patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who had 3 areas of CIS and had uneventful diagnostic autofluorescence bronchoscopy. The patient developed COPD exacerbation prior to PDT therapy but did not share his worsening symptoms with the investigators to avoid delay in PDT treatment. During PDT bronchoscopy thick mucopurulent secretions were seen in the airway. Since the patient had already received systemic HPPH, the investigators decided to treat him, but only one area of CIS (right middle lobe opening) was treated. In spite of this precaution, the patient developed significant mucus plugging of his right main stem and developed chest pain, and troponin-I elevation to 2.6 ng/ml after several hours. This delayed his bronchoscopy for removal of mucus plugs and he required emergent intubation. A right-sided pneumothorax was attributed to intrinsic positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) and pulmonary hyperinflation during resuscitation. The patient improved after removal of the mucus plug with bronchoscopy. Cardiac catheterization revealed 80% stenosis of the right coronary artery with probable insufficient flow reserve during times of respiratory failure. He had complete recovery to his baseline status and was discharged home. This SAE prompted the addition of evidence of recent exacerbation of chronic pulmonary disease (worsening dyspnea from baseline, fevers, increase purulence or change in color of sputum) and evidence of unstable angina or recent myocardial infarction (previous six months) to the study exclusion criteria. Because of this DLT, we added 3 more patients to this light dose cohort. Unfortunately only two more patients (a total of 5 patients at this dose group) could be recruited due to interruption in HPPH supply. Thus, although no more DLTs occurred, an MTD could not be firmly established. Accordingly, a light dose of 125 J/cm2 appears prudent for future HPPH PDT of endobronchial CIS/MIC.

Responses

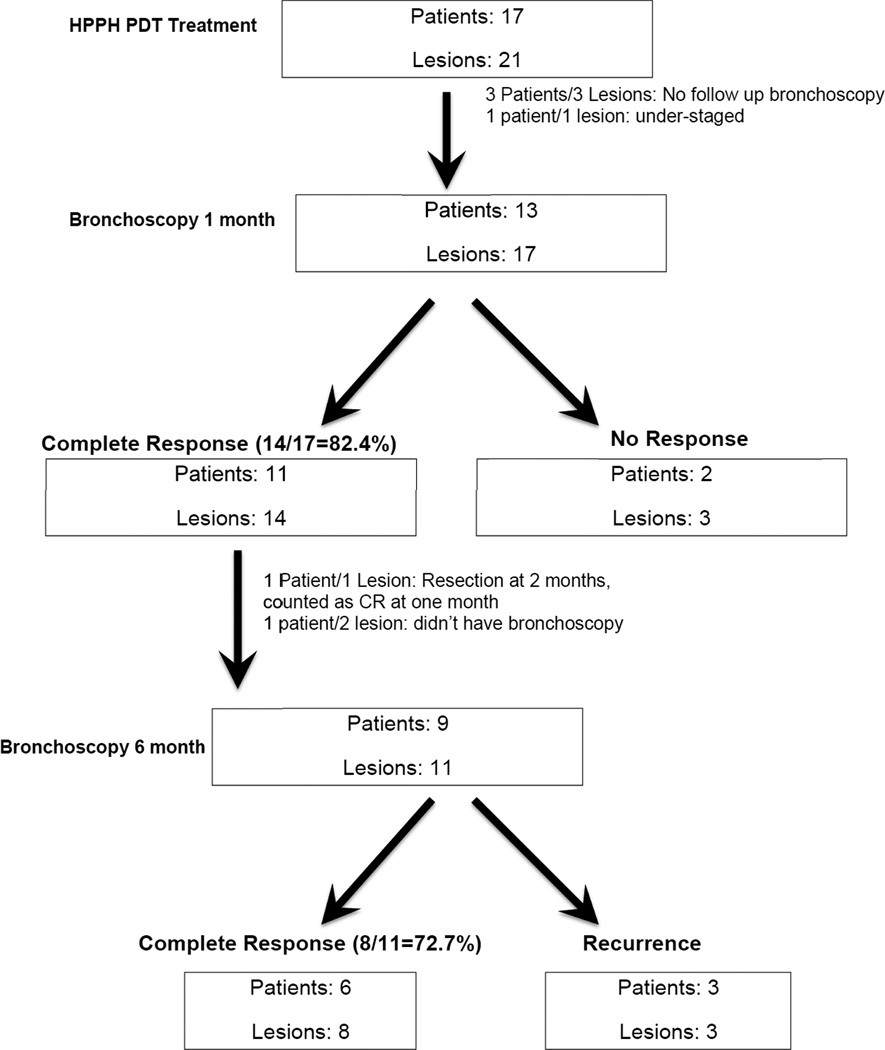

Lesion responses by light dose are presented in Table 2. A total of 21 lesions in 17 patients were treated and 14 patients/18 lesions had follow-up bronchoscopic evaluation after one month. Three patients (with one treated lesion each) didn’t have bronchoscopy at one month. One of these patients decided not to have follow-up bronchoscopy at 1 month due to initiation of chemotherapy for lung cancer not related to the CIS lesion, another suffered a stroke, the third patient was unable to withstand repeat bronchoscopy (this patient had SAE at 150 J/cm2). Of the 18 lesions, 17 were CIS and 1 was invasive carcinoma (determined retrospectively). Among the 17 CIS/MIC lesions, 13 achieved biopsy proven CR at 1-month post treatment. One patient was judged to have invasive cancer based on endobronchial biopsy at the 1-month follow-up. Upon lobectomy two months later, no cancer was detected. This patient was also considered a CR, thus bringing the CR rate for CIS to 14/17 or 82.4% at one month (Figure 1). CR occurred in all light dose cohorts and no light dose response was apparent in these small samples.

TABLE 2.

Lesion responses by treatment light dose (1 month post treatment)

| Light dose (J/cm2) | No. of lesions (responses) |

|---|---|

| 75 | 5 (3 CR, 2 NR) |

| 85 | 3 (2 CR, 1 not eval.) |

| 95 | 4 (3 CR, 1 not eval.) |

| 125 | 4 (3 CR, 1 NR) |

| 150 | 5 (3 CR, 1 NR#, 1 not eval.) |

Lesion was invasive carcinoma and was under-staged prior to treatment

CR indicates complete response and NR indicates no response

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing overall treatment response to HPPH PDT.

Eleven lesions in nine patients with previous CR could be re-evaluated with autofluorescence bronchoscopy and endobronchial biopsy at 6 months. Of these, 8 lesions in 6 patients were still CR and 3 single lesions in 3 separate patients had recurred thus bringing the CR to 72.7% (8/11) at 6 months in this evaluable group. Four patients with a total of five lesions opted for longer follow-up and had serial autofluorescent bronchoscopies for additional 1, 2, 2 and 5 years, respectively, and remained in CR. Management of Patients with No response (NR)

Three patients had NR (had remaining CIS on endobronchial biopsy) at one month. One of these was thought have been under-staged based on radial EBUS. Of the remaining 2 patients with 3 lesions who had NR at 1-month bronchoscopy, one patient had PDT with porfimer sodium to two separate lesions three months subsequent to HPPH PDT and decided not to do any further bronchoscopies and was lost to follow-up. Another patient with CIS in the left upper lobe apico-posterior segment with no response to HPPH was treated with porfimer sodium and had complete response.

Of the three patients who had recurred at 6 months, one was lost to follow-up and 2 were treated with porfimer sodium but did not have follow-up bronchoscopies to determine response due to underlying cardiopulmonary issues and patient preference.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that HPPH is safe and has favorable toxicity profile when compared to historical controls of porfimer sodium. It is also the first to evaluate its use for bronchogenic CIS/MIC. In this small cohort of patients we observed a promising CR rate of 82.4% and 72.7% of evaluable lesions at one and six month, respectively. This is within the range of response rates obtained by other studies with porfimer sodium4, 6, 8, 9, 23. All patients were smokers, four of the patients had multiple lesions and several patients had history of lung cancer. This is not unusual as a recent report describes a rate of 34.4% for multiple primary lung cancers in their cohort treated with PDT for CIS/MIC24.

Based on this and several other studies, an HPPH dose of 4 mg/m2 appears effective13–15. A 2-day drug/light interval was allowed in this trial. In more recently initiated studies the drug/light interval has been reduced to ~24 hours based on pharmacokinetic studies25 yielding at least comparable effectiveness14, 15. Although a maximally tolerated light dose could not be firmly established, the one SAE/DLT that occurred at 150 J/cm2 suggests that the light dose should not exceed 125 J/cm2. The absence of any discernible light dose dependence of treatment responses is reminiscent of studies in early esophageal13 and oral14 cancer and again suggests that PS uptake and retention in the cancerous lesion may be the dominant determinant of response. HPPH retention may be deficient in some lesions as has been shown in recent studies of lung and oral cancers26. Additional clinical studies will have to determine whether even lower light doses might be effective. Patient selection must be restricted to patients who can withstand repeated bronchoscopies, allowing for removal of PDT-induced debris and mucous plugs. These develop almost universally after PDT, regardless of the photosensitizer used7. Failure of timely debris removal may lead to serious consequences, as encountered in one patient with severe COPD who suffered a myocardial infarction shortly after treatment. No SAEs occurred in any of the other patients. Slight pain and/or cough were observed rarely and general photosensitivity was negligible. This shows that patients with CIS/MIC of airway can be treated with HPPH with significantly less concern of photosensitivity as compared to porfimer sodium, where a much higher rate of photosensitivity and skin burns (13–41% when treating CIS/MIC) has been historically reported8. All patients needed sunlight precautions for 7–10 days only as compared to 4–6 weeks needed for the most commonly used and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved porfimer sodium (Photofrin®). The HPPH supply is expected to resume soon for additional clinical trials. HPPH is currently being prepared under commercial manufacturing practices and a new Investigational New Drug (IND) application will be submitted shortly to the FDA.

Only preliminary insights into treatment response can be gleaned from this study, which was limited by the low patient numbers despite its long duration. Low patient accrual was due to the low yield of detection of CIS/MIC in the central airways, which has been similarly reported in other, studies27. The rate of squamous cell cancer which tends to be central has been declining, especially in men28. This makes it challenging to recruit patients who qualify for the study and are willing to enroll. Long-term evaluation is also problematic in this patient population, i.e. it is difficult to perform frequent bronchoscopies on these high-risk patients, many of whom tend to have multiple comorbidities and may not be willing to get additional bronchoscopic procedures. Although some patients did have longer follow up bronchoscopies and did not show any long term adverse sequele in the airway, it would have been ideal to have longer follow up bronchoscopic surveillance in a higher number of patients to confidently confirm the absence of any long term airway complications. These are extremely infrequent with PDT and none have been reported in studies where long-term follow up was done24, 29. The small sample size precludes us from making any conclusion about the HPPH PDT response rate based on lesion being nodular, hyperplastic or polypoidal. An additional confounding factor in studies of CIS/MIC is that it is very difficult to evaluate the depth of invasion, even with high-resolution computed tomography and PET imaging, recommended in prior studies. Thus, under-staging can occur. Radial balloon probe EBUS has been shown to be helpful in determining if there is deeper invasion into the cartilage as deeper invasion is thought to be associated with poor response to PDT30, 31.

One of the latest PDT trials for CIS/MIC utilized Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to look at depth of invasion22. Although using autofluorescence bronchoscopy to determine the superficial extent of lesions was a strength of our study, we didn’t have radial balloon probe EBUS for the first 15 cases, which would have otherwise enhanced the precision of lesion assessment. PDT studies using porfimer sodium have suggested that treating CIS/MIC lesions with longitudinal length >1 cm had less chance of CR as they tend to have deeper invasion5, 6. This perception of lack of efficacy of PDT of CIS/MIC >1 cm and cartilage invasion may however not be true for all PS agents. In the clinical trial of treatment of CIS with the PS mono-L-aspartyl chlorine e6 (talaporfin sodium, NPe6) which has an absorption band at 664 nm similar to HPPH, the authors reported good efficacy of NPe6 for lesions > 1 cm and with cartilage invasion22. In that trial, the large polypoid or nodular lesions were first debulked with electrocautery prior to PDT and the tumor depth was studied with Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT). In spite of these limitations, the data presented above support consideration of a phase 2 clinical trial of HPPH in early CIS/MIC of lung with the aim to recruit more patients and attempt longer duration of follow-up bronchoscopy. Involving multiple centers could help with increasing patient recruitment. Furthermore, the evolution of modern bronchoscopic technique like optical coherence tomography and radial probe EBUS along with autofluorescence bronchoscopy could help in determining the size and depth of the tumor in a much better fashion than the technology available when this clinical trial was initiated.

CONCLUSION

PDT with HPPH can be safely used for the treatment of CIS/MIC of the airways, with potential effectiveness comparable to porfimer sodium and much shorter need for light precaution and much lower incidence of skin photosensitivity as compared to skin photosensitivity reported with Photofrin in the prior studies.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants PO155791 (to BWH) and Roswell Park Cancer Institute Support Grant P30CA16056

Abbreviations

- PDT

Photodynamic Therapy

- PS

Photosensitizer

- HPPH

2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2 devinyl Pyropheophorbide-a

- CIS

Carcinoma-in-situ

- MIC

Microinvasive carcinoma

- MTD

Maximal tolerated dose

- DLT

Dose limited toxicity

- CR

Complete response

- NR

No response

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors do not have any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Dhillon SS, Loewen G, Jayaprakash V, et al. Lung cancer screening update. Journal of carcinogenesis. 2013;12:2. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.106681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels JM, Sutedja TG. Detection and minimally invasive treatment of early squamous lung cancer. Therapeutic advances in medical oncology. 2013;5:235–248. doi: 10.1177/1758834013482345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simone CB, 2nd, Friedberg JS, Glatstein E, et al. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of thoracic disease. 2012;4:63–75. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.11.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corti L, Toniolo L, Boso C, et al. Long-term survival of patients treated with photodynamic therapy for carcinoma in situ and early non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2007;39:394–402. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda N, Usuda J, Kato H, et al. New aspects of photodynamic therapy for central type early stage lung cancer. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2011;43:749–754. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuse K, Fukuoka M, Kato H, et al. A prospective phase II study on photodynamic therapy with photofrin II for centrally located early-stage lung cancer. The Japan Lung Cancer Photodynamic Therapy Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:1852–1857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loewen GM, Pandey R, Bellnier D, et al. Endobronchial photodynamic therapy for lung cancer. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2006;38:364–370. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moghissi K, Dixon K. Is bronchoscopic photodynamic therapy a therapeutic option in lung cancer? The European respiratory journal. 2003;22:535–541. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00005203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Usuda J, Kato H, Okunaka T, et al. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) for lung cancers. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2006;1:489–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Usuda J, Tsutsui H, Honda H, et al. Photodynamic therapy for lung cancers based on novel photodynamic diagnosis using talaporfin sodium (NPe6) and autofluorescence bronchoscopy. Lung cancer. 2007;58:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato H, Furukawa K, Sato M, et al. Phase II clinical study of photodynamic therapy using mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 and diode laser for early superficial squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Lung cancer. 2003;42:103–111. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Nava H, et al. Mild skin photosensitivity in cancer patients following injection of Photochlor (2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a; HPPH) for photodynamic therapy. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2006;57:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nava HR, Allamaneni SS, Dougherty TJ, et al. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) using HPPH for the treatment of precancerous lesions associated with Barrett's esophagus. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2011;43:705–712. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigual N, Shafirstein G, Cooper MT, et al. Photodynamic therapy with 3-(1'-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide a for cancer of the oral cavity. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:6605–6613. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shafirstein G, Rigual NR, Arshad H, et al. Photodynamic Therapy with 3-(1'-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide a (HPPH) for Early Stage Cancer of the Larynx- Phase Ib Study. Head & neck. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hed.24003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y, Shih WJ. Statistical properties of the traditional algorithm-based designs for phase I cancer clinical trials. Biostatistics. 2001;2:203–215. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loewen G, Reid M, Tan D, et al. Bimodality lung cancer screening in high-risk patients: a preliminary report. Chest. 2004;125:163S–164S. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.5_suppl.163s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loewen G, Natarajan N, Tan D, et al. Autofluorescence bronchoscopy for lung cancer surveillance based on risk assessment. Thorax. 2007;62:335–340. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.068999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayaprakash V, Loewen GM, Dhillon SS, et al. Early Detection of Lung Cancer Using CT Scan and Bronchoscopy in a High Risk Population. Journal of Cancer Therapy. 2012;3:388–396. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam S, Kennedy T, Unger M, et al. Localization of bronchial intraepithelial neoplastic lesions by fluorescence bronchoscopy. Chest. 1998;113:696–702. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato H, Usuda J, Okunaka T, et al. Basic and clinical research on photodynamic therapy at Tokyo Medical University Hospital. Lasers in surgery and medicine. 2006;38:371–375. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usuda J, Ichinose S, Ishizumi T, et al. Outcome of photodynamic therapy using NPe6 for bronchogenic carcinomas in central airways >1.0 cm in diameter. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:2198–2204. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simone CB, 2nd, Cengel KA. Photodynamic therapy for lung cancer and malignant pleural mesothelioma. Seminars in oncology. 2014;41:820–830. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usuda J, Ichinose S, Ishizumi T, et al. Management of multiple primary lung cancer in patients with centrally located early cancer lesions. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2010;5:62–68. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c42287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Loewen GM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of the photodynamic therapy agent 2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a in cancer patients. Cancer research. 2003;63:1806–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tracy EC, Bowman MJ, Pandey RK, et al. Cell-type selective phototoxicity achieved with chlorophyll-a derived photosensitizers in a co-culture system of primary human tumor and normal lung cells. Photochemistry and photobiology. 2011;87:1405–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edell E, Lam S, Pass H, et al. Detection and localization of intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma using fluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy: an international, multicenter clinical trial. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2009;4:49–54. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181914506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devesa SS, Bray F, Vizcaino AP, et al. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: male:female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;117:294–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Endo C, Miyamoto A, Sakurada A, et al. Results of long-term follow-up of photodynamic therapy for roentgenographically occult bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. Chest. 2009;136:369–375. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurimoto N, Murayama M, Yoshioka S, et al. Assessment of usefulness of endobronchial ultrasonography in determination of depth of tracheobronchial tumor invasion. Chest. 1999;115:1500–1506. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.6.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi H, Sagawa M, Sato M, et al. A prospective evaluation of transbronchial ultrasonography for assessment of depth of invasion in early bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. Lung cancer. 2003;42:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]