Abstract

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is the primary etiological agent responsible for cervical cancer in women. Although in total 16 high-risk HPV strains have been identified so far. Currently available commercial vaccines are designed by targeting mainly HPV16 and HPV18 viral strains as these are the most common strains associated with cervical cancer. Because of the high level of antigenic specificity of HPV capsid antigens, the currently available vaccines are not suitable to provide cross-protection from all other high-risk HPV strains. Due to increasing reports of cervical cancer cases from other HPV high-risk strains other than HPV16 and 18, it is crucial to design vaccine that generate reasonable CD8+ T-cell responses for possibly all the high-risk strains. With this aim, we have developed a computational workflow to identify conserved cross-clade CD8+ T-cell HPV vaccine candidates by considering E1, E2, E6 and E7 proteins from all the high-risk HPV strains. We have identified a set of 14 immunogenic conserved peptide fragments that are supposed to provide protection against infection from any of the high-risk HPV strains across globe.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-015-0352-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: HPV, Epitope, Cytotoxic, T lymphocytes, Cervical cancer, Vaccine

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common malignant cancer in terms of incidence and mortality rates in women worldwide after breast cancer (Pisani et al. 1993; Collins et al. 2006; Jemal et al. 2011; Senapathy et al. 2011; Torre et al. 2015). Human papilloma virus (HPV) is considered as the major etiological agent for cervical cancer which is responsible for over 265,700 total women deaths per year with around 527,600 new cases every year (Torre et al. 2015). It is estimated that about 80 % of women could acquire a HPV infection in their lifetime (Baseman and Koutsky 2005). On an average, every woman who dies due to cervical cancer loses about 26 years of life which is considerably greater than the average years of life lost to breast cancer (19.2 years) (Herzog and Wright 2007; Pandhi and Sonthalia 2011). Till now over 200 types of HPV strains have been sequenced (Bernard et al. 2010; Meiring et al. 2012; McLaughlin-Drubin 2015; Supindham et al. 2015), among them 16 are known to be high-risk virus strains (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 69, 73, and 82) (Muñoz et al. 2003; Markowitz et al. 2007; Sumalee et al. 2008; Meijer et al. 2009; Dames et al. 2014) with oncogenic HPV DNAs detected in 99 % of the cervical cancers (Dunne et al. 2007). High-risk HPV strains are in most of the cases identified as main etiological agents in cervical, anal, and other genital cancers, among them about 70 % of cervical cancers worldwide are only due to HPV strains 16 and 18 (Dunne et al. 2007). For the primary prevention of cervical cancer, HPV vaccines are widely used as an important added tool (Ault et al. 2004; Fife et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2012). Prophylactic and the therapeutic formulation are the two strategies for cervical cancer vaccine candidates. Recently, FDA approved a vaccine named ‘Gardasil 9’ that protects females between the ages of 9–26 against nine HPV strains. More specifically, the first generation of Gardasil vaccine was capable to provide protections against four HPV strains (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, and HPV-18) while the latest approved version of Gardasil vaccine (Gardasil 9) provides protection against five additional high-risk HPV strains (HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58) responsible for almost 20 % of cervical cancers worldwide (Braaten and Laufer 2008; Petrosky et al. 2015). Gardasil and Cervarix are prophylactic vaccines and offer no therapeutic benefit for persons already infected with HPV (Wain 2010; Pandhi and Sonthalia 2011). Most of the vaccine candidates that can be used as therapeutic vaccines include immunogenic fragments from early proteins (targets for cellular immunity) for the resolution of precancerous lesions and cervical cancer (Huh and Roden 2008). The protection offered by current vaccines is primarily against HPV types (16 and 18), although cross-protection for other high-risk HPV strains cannot be neglected. The identification of highly conserved cross-clade epitopes suitable for therapeutic intervention is clearly a crucial prerequisite for epitope-based vaccines development and for diagnostic tests to distinguish infection from high or low risk HPV strains. Cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) cross-reactivity is alleged to play an essential role in generating immune responses (Frankild et al. 2008; Petrova et al. 2012). HPV-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes immune responses can be detected in all untreated cervical cancer patients (Eiben et al. 2002; Valdespino et al. 2005). In animal models, cell-mediated immunity is considered to be an important mechanism for abolition of subclinical or neoplasic virus-infected cells, particularly CTL which lyses tumor cells in an antigen-specific manner (Chen et al. 1991; Feltkamp et al. 1993; De Bruijn et al. 1998; Torres-Poveda et al. 2014). Instead of individual epitopes, the use of the full-length protein with a great amount of immunogenic peptides may have a better chance to induce specific CTLs, as shown previously (Strobel et al. 2000; Adams et al. 2003; Bet et al. 2015) but the protection from all high-risk HPV strains from single vaccination will still be a question. Selection of immunogenic consensus conserved epitopes from the proteins of all HPV high-risk strains may provide an experimental basis for designing of universal HPV T-cell vaccines. In the present work, we identified conserved consensus immunogenic CD8+ T-cell epitopes from the proteome of all high-risk HPV strains and proposed a peptide pool with the ability to show immunogenic responses against all the known high-risk HPV strains.

Materials and methods

Sequence retrieval

Complete proteome of all the 16 high-risk HPV strains was retrieved from UniProt Knowledgebase (Apweiler et al. 2004). Amino acid sequences of four HPV proteins E1, E2, E6 and E7 were extracted from all the selected proteomes. Subsequently, four sequence datasets were manually prepared for each of the proteins from 16 high-risk HPV strains.

Conservancy analysis

For conservancy analysis, sequence datasets were first individually aligned using ClustalW software. The substitution model was set to BLOSUM, since the mentioned substitution matrix is based on amino acid pairs in blocks of aligned protein segments, hence performs better in alignments and homology searches compared to those based on accepted mutations in closely related groups (Henikoff and Henikoff 1992). Conservancy of the amino acids of HPV strains among the aligned sequences of datasets was estimated by Shannon entropy function using protein variability server (PVS). Shannon entropy analysis (Shannon 1948) is one of the most sensitive tools to estimate the diversity of a system. For a multiple protein sequence alignment, the Shannon entropy (H) for every position is calculated as follows

where Pi is the fraction of residues of amino acid type i and M is the number of amino acid types.

Consequently, consensus sequences were created for individual conserved fragments within Shannon entropy threshold 2 from corresponding aligned sequence datasets (Gupta et al. 2012). The consensus sequences were further used for the identification of MHC binders.

Prediction of MHC binders

The most selective step in the presentation of antigenic peptides to T-cell receptor (TCR) is the binding of the peptide to the MHC molecule (Yewdell and Bennink 1999). NetMHC 3.2 server was used to predict binding of peptides to a number of different HLA alleles using artificial neural networks (ANNs) and weight matrices. Position specific scoring matrices (PSSMs)-based SYFPEITHI (Rammensee et al. 1999) method was employed for the prediction of binding peptides of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I. NetMHC 3.2 predicts epitopes with length ranging from 8 to 11 amino acids. Only epitopes with IC50 value below 500 nM were considered as the potential epitopes in ANNs-based prediction from the consensus fragments for four protein datasets. As the epitopes were predicted from the consensus sequences of conserved protein fragments, these epitopes were again realigned with E1, E2, E6 and E7 proteins of all high-risk HPV strains. Only those epitopes were kept for subsequent analyses which were 100 % identical to their respective proteins. Further, we performed common allele matrix analysis (Gupta et al. 2010) to discard those epitopes whose allelic response is coverd by more efficient epitopes from the same high-risk HPV strain.

Prediction of non-human homologous immunogenic peptide fragments

All the overlapping epitopes (9 mer) were merged to design the potential immunogenic peptide fragments for CD8+ response from each of the protein datasets. A number of immunogenic peptides may fail to raise a T-cell response if they are recognized as self peptides due to significant similarity exists between the antigenic peptides and proteins of host organism. For this, the final sets of potential immunogenic peptide fragments were checked for their similarities with annotated human proteins using offline BLAST similarity search.

Population coverage analysis

Population coverage analysis plays a significant role in the epitope-based vaccine designing because of the highly polymorphic nature of the MHC molecules (Reche and Reinherz 2003; Stern and Wiley 1994). Population coverage of newly identified immunogenic peptide fragments were individually analyzed using population coverage tool available at IEDB web server. The tool calculates the response of individuals set of peptide fragments with known MHC- I restrictions on the basis of maximum HLA binding alleles. The average projected population coverage of class I epitopes for the populations distributed in various human populations (ethnicities) was estimated.

Results

The E1, E2, E6 and E7 protein sequences from all high-risk HPV strains were collected from UniProtKB and aligned using multiple sequence alignment software clustalW. The multiple alignment files for all the four protein data sets with conserved regions are shown in Supplementary File 1. The conserved fragments within aligned strains of sequence datasets were analyzed by PVS with variability threshold (H) ≤ 2.0. Typically, positions with H ≥ 2.0 are considered variable, whereas those with H ≤ 1 are consider highly conserved (Litwin and Jores 1992). Additionally the positions with H ≤ 2 and H > 1 are also considered as conserved regions (Gupta et al. 2009, 2011). The default cutoff value (H = 1) was too strict, resulting in fewer and smaller targets for the following analysis so the cutoff threshold value was set as 2.0 in the present analysis to identify reasonable conserved fragments with length ≥9 amino acid residues. The consensus sequences of all the conserved regions with length ≥9 amino acids in four datasets of E1, E2, E6 and E7 proteins from high-risk HPV strains are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Conserved protein fragments from E1, E2, E6 and E7 protein datasets from all high-risk HPV strains

| HPV protein | Conserved fragment number | Start position | End position | Sequence with nine or more consecutive conserved residues filtered from protein variability server |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | E1-1 | 2 | 12 | MADPEGTDGEG |

| E1-2 | 21 | 31 | VEAIVEKKTGD | |

| E1-3 | 33 | 41 | ISDDEDENA | |

| E1-4 | 66 | 76 | ETAQALFNAQE | |

| E1-5 | 135 | 146 | PDSGYGNTEVET | |

| E1-6 | 241 | 257 | ELVRPFKSDKTTCTDWV | |

| E1-7 | 265 | 278 | PSVAEGLKTLIKPY | |

| E1-8 | 291 | 307 | WGVIILMLIRFKCGKNR | |

| E1-9 | 312 | 321 | KLLSTLLNVP | |

| E1-10 | 324 | 334 | CMLIEPPKLRS | |

| E1-11 | 336 | 352 | AAALYWYRTGISNISEV | |

| E1-12 | 362 | 373 | RQTVLQHSFDDS | |

| E1-13 | 375 | 388 | FDLSEMVQWAFDND | |

| E1-14 | 406 | 447 | NSNAAAFLKSNCQAKYVKDCATMCRHYKRAQKRQMSMSQWIK | |

| E1-15 | 455 | 474 | DGGDWRPIVQFLRYQGVEFI | |

| E1-16 | 483 | 516 | FLKGTPKKNCIVIYGPANTGKSYFGMSLIHFLQG | |

| E1-17 | 535 | 545 | DAKIAMLDDAT | |

| E1-18 | 555 | 572 | YMRNALDGNPISIDRKHR | |

| E1-19 | 574 | 590 | LVQLKCPPLLITSNINP | |

| E1-20 | 595 | 606 | RWPYLHSRLTVF | |

| E1-21 | 624 | 642 | INDKNWKSFFSRTWSRLDL | |

| E1-22 | 645 | 653 | EEEDKENDG | |

| E2 | E2-1 | 7 | 26 | METLSQRLNVCQDKILDHYE |

| E2-2 | 45 | 54 | ECAIFYKARE | |

| E2-3 | 77 | 89 | QAIELQMALESLN | |

| E2-4 | 110 | 118 | TEPKKCFKK | |

| E2-5 | 204 | 212 | CPESVSSTS | |

| E2-6 | 305 | 314 | TTPIVHLKGD | |

| E6 | E6-1 | 14 | 23 | ERPRKLHDLC |

| E6-2 | 25 | 33 | ALETSLHDI | |

| E6-3 | 76 | 86 | FYSKISEYRHY | |

| E6-4 | 113 | 127 | CQKPLCPEEKQRHLD | |

| E6-5 | 129 | 137 | KKRFHNIAG | |

| E7 | E7-1 | 6 | 15 | PTLQDIVLDL |

| E7-2 | 95 | 103 | LQQLLMGTL |

To generate immunological responses against any pathogen, the binding of antigenic peptide from pathogen and its binding affinity to MHC molecules is one of the crucial steps (Roomp et al. 2010). Using NetMHC 3.2 server, we predicted a total of 65 unique epitopes from the consensus sequences dataset of E1 protein. Likewise, 8 from E2, 5 from E6 and 2 unique epitopes from E7 protein consensus sequence datasets were predicted by the server with either strong or weak binding affinity (Supplementary Table 1–4). As epitopes were predicted from the consensus conserved peptide fragments of protein datasets through NetMHC 3.2 server, there are chances that some of the epitopes may not show 100 % identity with any of the protein in the datasets due to presence of consensus amino acid residues substituted during conservancy analysis. To verify this, epitopes were realigned with the primary protein datasets of E1, E2, E6 and E7 proteins collected for various high-risk HPV strains. Those epitopes which were not completely mapped with any of the primary protein sequences of high-risk HPV strains were filtered out. In this process, 16 epitopes from E1, 2 from E2, 2 from E6 and both the epitopes from E7 datasets were discarded. To predict the long immunogenic peptide fragments, all the overlapping epitopes were merged (Table 2). In total, 15 immunogenic conserved peptide fragments were identified, of which 11 fragments were from E1, 3 from E2 and 1 fragment was from E6 protein dataset of high-risk HPV strains.

Table 2.

Immunogenic peptide fragments identified from selected protein datasets of high-risk HPV strains

| HPV protein fragment | Immunogenic peptide sequence | HLA alleles targeted | High-risk HPV strains mapped | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein name | Immunogenic peptide fragment | |||

| E1 | E1-F1 | DSGYGNTEV | HLA-A6802 | 16, 31, 33, 58, 73 |

| E1-F2 | LVRPFKSDK | HLA-A0301,HLA-A3001 | 33, 58 | |

| E1-F3 | CMLIEPPKL | HLA-A0201,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0212,HLA-A0216,HLA-A0219,HLA-A0250 | 45, 59 | |

| E1-F4 | ALYWYRTGISNISEV | HLA-A0201,HLA-A0202,HLA-A0203,HLA-A0206,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0212,HLA-A0216,HLA-A0250,HLA-A2301,HLA-A2403,HLA-A6802 | 16, 18, 39, 45, 68 | |

| E1-F5 | DLSEMVQWAFD | HLA-A0203,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0216,HLA-A0219,HLA-A0250,HLA-B4501 | 18, 33, 35 | |

| E1-F6 | NSNAAAFLKSNCQAKYVKDCATMCRHYKRAQKRQMSMSQWIK | HLA-A0201, HLA-A0202,HLA-A0203,HLA-A0206,HLA-A2402,HLA-A3201,HLA-B1501,HLA-B1503,HLA-B2705,HLA-A0301,HLA-A1101,HLA-A6801,HLA-B1503,HLA-A3001,HLA-B0702,HLA-B0801,HLA-B1517,HLA-B5801,HLA-A3101,HLA-A3301,HLA-A2301,HLA-A2403,HLA-A3002,HLA-A6801 | 39, 59, 16, 68, 45, 31, 35, 52, 69, 39, 51, 82, 18 | |

| E1-F7 | WRPIVQFLRYQGVEFI | HLA-B2705,HLA-B3501, HLA-B5301,HLA-A0203,HLA-A0206,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0216,HLA-A0250, HLA-B1503 | 18, 39, 45, 58, 68, 56, 59 | |

| E1-F8 | PKKNCIVIYGPANTGKSYFGMSLIHFL | HLA-A0201,HLA-A0202,HLA-A0206,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0216,HLA-A6802,HLA-A6901,HLA-B3901,HLA-A2301,HLA-A2402, HLA-A2403,HLA-A2902,HLA-B1501,HLA-A0203,HLA-A3001,HLA-A3201,HLA-B1517,HLA-B5801,HLA-B1503,HLA-A2603,HLA-B1502,HLA-B3501,HLA-B1503 | 18, 58, 31, 33, 52, 59, 45, 39 | |

| E1-F9 | VQLKCPPLLITSNI | HLA-B5301,HLA-A0203,HLA-A0201,HLA-A0206,HLA-B1503,HLA-B3901,HLA-B4801 | 16, 31, 33, 35, 51 | |

| E1-F10 | RWPYLHSRLTVF | HLA-A0202,HLA-A0203,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0250,HLA-B0801,HLA-B1501,HLA-B1502,HLA-B1503,HLA-B1517,HLA-B3501,HLA-B5401,HLA-A2402,HLA-A2403 | 31, 33, 52, 58, 68 | |

| E1-F11 | KNWKSFFSRTWSRL | HLA-A2301,HLA-A2403,HLA-A1101,HLA-A3101,HLA-A3301,HLA-A6801,HLA-B1503,HLA-A3101 | 16, 31, 33, 35, 52, 58 | |

| E2 | E2-F1 | ETLSQRLNVCQDKI | HLA-A0202,HLA-A0203,HLA-A0212,HLA-A0219,HLA-A6802,HLA-A6901 | 16, 31 |

| E2-F2 | ECAIFYKAR | HLA-A6801 | 69 | |

| E2-F3 | QAIELQMALESL | HLA-A0202,HLA-A0211,HLA-A0219,HLA-A0250,HLA-B4002,HLA-A0206,HLA-A6802,HLA-A6901,HLA-B3501,HLA-B3901 | 39, 59, 68 | |

| E6 | E6-F1 | FYSKISEYRHY | HLA-A2602,HLA-B1503,HLA-B1517,HLA-A2403,HLA-A3101,HLA-A3301,HLA-A6801 | 16, 33, 35, 52, 58 |

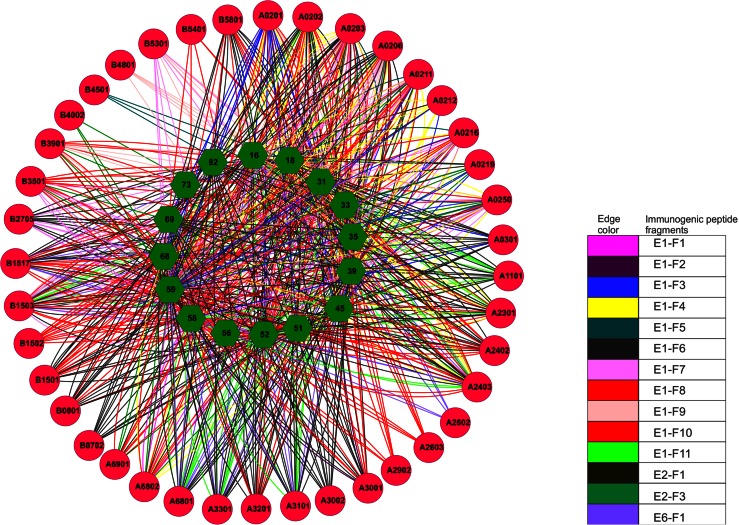

To further identify the minimal set of immunogenic peptide fragment datasets to target all the high-risk HPV strains, we discarded those peptide fragments where the targeted HLA alleles and high-risk HPV strains were the subsets of other highly efficient peptide fragments shown in Table 2. In this process, immunogenic peptide sequence ECAIFYKAR (Table 2: E2-F2) from the high-risk HPV strain 69 was filtered out as it can be considered the subset of immunogenic fragment E1-F6 which is also present in type 69 HPV strain and also target the same allele besides its affinity with other alleles. Thus, in total, we have identified a peptide pool of 14 sequences that might be effective to generate immunogenic responses against any of the high-risk HPV strains. The interaction map of immunogenic peptide fragments, their HLA allelic responses and their presence in various HPV high-risk strains are shown in Fig. 1. To discard peptide fragments that can be recognized as self protein for the immune system we performed BLAST screening of all the 14 immunogenic peptides with entire human proteome. None of the peptide was similar to human proteome. We finally performed the population coverage analysis of generated immunogenic peptide pool using population coverage analysis tool available at IEDB server (http://tools.immuneepitope.org/tools/population). The percentage population coverage of the immunogenic peptide pool generated from the current analysis in various ethnicities is shown in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the interaction network of immunogenic peptide fragments, High-risk HPV strains which contributed for the formation of these fragments and MHC class I alleles are shown. Edges with different colors represent various immunogenic peptide fragments as shown in figure legends. High-risk HPV strains are shown in green hexagon in the inner circle and HLA alleles on the outer circle with red color. From the figure it is clear that few alleles (e.g. A2602, A2603, A2902, A3002, B0702, B1502, B4002, B4501, B4801, B5401) are targeted by only one immunogenic peptide fragments, while majority of HLA alleles (A0201, A0202, A0203, A0206, A0211, A0212, A0216, A0219, A0250, A0301, A1101, A2301, A2402, A2403, A3001, A3101, A3201, A3301, A6801, A6802, A6901, B0801, B1501, B1503, B1517, B2705, B3501, B3901, B5301, B5801) are targeted by most of the immunogenic peptides selected in this study

Table 3.

Population coverage analysis for immunogenic peptide pooled in various ethnicities

| High-risk HPV strain | Percentage population coverage in various ethnicities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia (%) | Europe (%) | North Africa (%) | North America (%) | North-East Asia (%) | Oceania (%) | South America (%) | South-East Asia (%) | South-West Asia (%) | Sub-Saharan Africa (%) | |

| TYPE 16 | 81.24 | 94.35 | 63.21 | 95.17 | 69.98 | 88.73 | 53.15 | 86.72 | 79.18 | 85.14 |

| TYPE 18 | 65.40 | 74.28 | 50.63 | 91.46 | 60.15 | 76.33 | 53.56 | 73.07 | 64.57 | 76.17 |

| TYPE 31 | 81.33 | 95.31 | 65.99 | 96.89 | 76.13 | 91.12 | 54.37 | 89.97 | 81.73 | 86.83 |

| TYPE 33 | 80.85 | 92.30 | 64.35 | 95.03 | 74.60 | 91.06 | 53.76 | 89.76 | 80.19 | 83.36 |

| TYPE 35 | 81.24 | 94.15 | 62.30 | 95.14 | 69.90 | 88.73 | 52.88 | 86.69 | 78.19 | 82.91 |

| TYPE 39 | 81.29 | 95.30 | 65.99 | 95.88 | 71.40 | 89.45 | 54.17 | 87.99 | 81.60 | 86.83 |

| TYPE 45 | 81.29 | 95.30 | 65.99 | 95.88 | 71.40 | 89.45 | 54.17 | 87.99 | 81.60 | 86.83 |

| TYPE 51 | 81.24 | 94.04 | 56.96 | 95.04 | 68.92 | 88.73 | 48.71 | 86.55 | 77.50 | 79.99 |

| TYPE 52 | 81.29 | 95.30 | 65.99 | 95.88 | 74.42 | 89.58 | 54.17 | 88.72 | 81.51 | 86.83 |

| TYPE 56 | 0.49 | 17.12 | 8.63 | 40.71 | 18.50 | 2.56 | 8.86 | 14.30 | 15.98 | 23.50 |

| TYPE 58 | 80.85 | 92.75 | 59.07 | 95.17 | 74.34 | 89.51 | 53.56 | 88.50 | 79.96 | 80.90 |

| TYPE 59 | 81.29 | 95.30 | 65.99 | 95.88 | 71.40 | 89.45 | 54.17 | 87.99 | 81.60 | 86.83 |

| TYPE 68 | 81.29 | 95.30 | 65.99 | 95.88 | 73.51 | 89.58 | 54.17 | 88.47 | 81.60 | 86.83 |

| TYPE 69 | 80.40 | 93.85 | 55.85 | 93.45 | 65.25 | 86.26 | 44.60 | 83.12 | 77.29 | 79.75 |

| TYPE 73 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 9.82 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.63 | 14.68 |

| TYPE 82 | 80.40 | 93.85 | 55.85 | 93.45 | 65.25 | 86.26 | 44.60 | 83.12 | 77.29 | 79.75 |

Discussion

In the post-genomic era, strategies of vaccine development have progressed dramatically from traditional Pasteur’s principles of isolating, inactivating and injecting the causative agent of an infectious disease, to reverse vaccinology that initiates from in silico analysis of the genome information (Akhoon et al. 2011). In silico works have attracted considerable attention of experimental biologists for rapid screening and identification of probable vaccine candidates (Sakib et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2013; Hasan et al. 2013; Oany et al. 2014). The availability of fully sequenced proteome from high-risk HPV strains provide an opportunity for computer-aided screening of reliable peptide-based therapeutic vaccines candidates among billions of possible immune-active peptides.

We extracted high-risk HPV proteome for 8 HPV specific proteins designated as E- (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6 and E7) or L-type (L1 and L2) according to their expression in early or late differentiation stage of the epithelium (Burd 2003; Rautava and Syrjänen 2012). The early secretary proteins expressed during early differentiating stage of epithelium development in all the 16 high-risk HPV strains. Since the E5 protein of HPV has previously been reported as inducer of down-regulation of MHC class I, we ignored E5 protein in the current analysis. Moreover, E2–E5 region has been shown to be lost when the episomal HPV DNA integrates into host chromosome; using E2–E5 proteins as vaccine candidates may be futile. However, since E1 and E2 are expressed in higher levels than E6 and E7 early in the progress of an HPV infection, it may be assumed that these proteins may considered as good targets for vaccine designing to treat early stages of disease (Burd 2003). Therefore, E2 protein was included for epitope-based vaccine designing in the present study along with E1, E6 and E7 protein. Based on our computational workflow, we generated a pool of 14 peptide fragments with length varying from 9 to 43 amino acid residues to provide immunogenic responses against all the high-risk HPV strains. The hallmark of the immune system is its ability to recognize and distinguish between self and non-self. T-cells do this task by recognizing peptides that are bound to MHC receptors. Epitopes are usually thought to be derived from non-self protein antigen that interacts with antibodies or T-cell receptors, thereby activating an immune response. Epitopes are usually thought to be derived from non-self protein antigen that interacts with antibodies or T-cell receptors, thereby activating an immune response. Also the antigen–antibody interaction is reversible, therefore, weak interactions often lead to cross-reactivity of antigens. The main reasons of cross-reactivity are either the homologous proteins that are conserved throughout the development and expressed by both the infectious agent and the host or the viral proteins that share short regions of amino acid sequence similarity with a non-homologous host protein. Therefore, to exclude the epitopes those are conserved between the pathogen and the host, we performed sequence alignment of the selected pool of 14 immunogenic peptides with entire human proteome. We did not observe similarity between any of the selected immunogenic peptide fragments with human proteome, we also discarded epitopes showing weak interactions with HLA alleles. Thus we believe that all the 14 sequences together will form the best peptide pool to generated immunogenic responses against any of the high-risk HPV strains infection.

Population coverage analysis for a given set of immunogenic peptides is important to determine their efficacy as the frequency of expression of their targeted HLA alleles varies across ethnicities. With the population coverage analysis, we concluded that least immunogenic response is shown by HPV strain 73 followed by strain 56 in almost all the ethnicities. Thus, the data indicate that the generated peptide fragments pool will provide very weak protection against HPV Type 73 and 56. The best response is shown by North American population for all the HPV high-risk strains based on the HLA alleles frequency data. Overall, we proposed the pool of 14 immunogenic peptide fragments with length ranging from 9 to 43 amino acid residues to provide the protection against all the HPV high-risk strains except Type 73 and 56 in all the ethnicities.

Conclusion

Immunoinformatics has changed the paradigm of ancient vaccinology since it is recently emerged as a critical field for accelerating immunology research (Baloria et al. 2012). Moreover, the immunoinformatics techniques applied to T-cells have advanced to a greater degree than those dealing with B-cells. Indeed, it is now a common practice to identify the vaccine candidates using in silico approaches before being subjected to in vitro confirmatory studies (Gupta et al. 2009; Ranjbar et al. 2015). The major objective of our study was to identify an immunogenic peptide pool containing epitopes that can be effective against all the high-risk HPV strains circulating globally. Some cross-protections were already observed in case of previously identified vaccines. Such as, Cervarix vaccine which was initially designed by targeting HPV 16 and 18 strains but later found to provide additional cross-protections against HPV 31, 33 and 45 strains. However, most of the high-risk HPV strains were evolved by accumulating random mutations in the epitopes recognizing regions and therefore many of the high-risk strains are not effectively targeted by available HPV vaccines. Therefore, we used the consensus epitopes extracted from highly conserved regions of E1, E2, E6 and E7 proteins from all the high-risk HPV strains identified so far. The vaccine formulated by the proposed peptide pool can alert the body’s immune system to generate immunization memory cells upon injecting. Subsequently, as these are MHC class I epitopes, the proteasomal degradation machineries can degrade the whole vaccine and release these conserved epitopes in host. Furthermore, because of the conserved nature of the epitopes the immune system will be trained to recognize these epitopes in case of HPV infection by any high-risk strains and thus can provide the cross-protection. Using the computational workflow presented in this manuscript, we identified 14 conserved immunogenic peptide fragments from 4 early proteins (E1, E2, E6 and E7) of 16 high-risk HPV types providing CD8+ responses which can be validated experimentally for the designing of an universal vaccine against all the high-risk HPV strains.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

KPS, BAA, SKG acknowledge financial support from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) India network project GENESIS (BSC0121) and INDEPTH (BSC0111), NV and VB was financially supported by Society for Biological Research & Rural Development, India.

Abbreviations

- HPV

Human papilloma virus

- CTL

Cytotoxic T-cell

- PVS

Protein variability server

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- PSSMs

Position specific scoring matrices

- ANN

Artificial neural network

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Krishna P. Singh and Neeraj Verma have contributed equally to this article.

References

- Adams M, Navabi H, Jasani B, Man S, Fiander A, Evan AS, Donningerc C, Mason M. Dendritic cell (DC) based therapy for cervical cancer: use of DC pulsed with tumour lysate and matured with a novel synthetic clinically non-toxic double stranded RNA analogue poly [I]:poly [C(12)U] (Ampligen R) Vaccine. 2003;21:787–790. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhoon BA, Slathia PS, Sharma P, Gupta SK, Verma V. In silico identification of novel protective VSG antigens expressed by Trypanosoma brucei and an effort for designing a highly immunogenic DNA vaccine using IL-12 as adjuvant. Microb Pathog. 2011;51:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apweiler R, Bairoch A, Wu CH, Barker WC, Boeckmann B, Ferro S, Gasteiger E, Huang H, Lopez R, Magrane M, Martin MJ, Natale DA, O’Donovan C, Redaschi N, Yeh LS. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D115–D119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ault KA, Giuliano AR, Edwards RP, Tamms G, Kim LL, Smith JF, Jansen KU, Allende M, Taddeo FJ, Skulsky D, Barr E. A phase I study to evaluate a human papillomavirus (HPV) type 18 L1 VLP vaccine. Vaccine. 2004;22:3004–3007. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloria U, Akhoon BA, Gupta SK, Sharma S, Verma V. In silico proteomic characterization of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) for the mapping of high affinity antigenic determinants against breast cancer. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1349–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0830-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseman JG, Koutsky LA. The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infections. In J Clin Virol. 2005;32:S16–S24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HU, Burk RD, Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, zur Hausen H, de Villiers EM. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology. 2010;401:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bet A, Maze EA, Bansal A, Sterrett S, Gross A, Graff-Dubois S, Samri A, Guihot A, Katlama C, Theodorou I, Mesnard JM, Moris A, Goepfert PA, Cardinaud S. The HIV-1 Antisense Protein (ASP) induces CD8 T cell responses during chronic infection. Retrovirolo. 2015;10:12–15. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braaten KP, Laufer MR. Human Papillomavirus (HPV), HPV-related disease, and the HPV vaccine. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1:2–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Thomas EK, Hu SL, Hellström I, Hellström KE. Human papillomavirus type 16 nucleoprotein E7 is a tumor rejection antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:110–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins Y, Einstein MH, Gostout BS, Herzog TJ, Massad LS, Rader JS, Wright J. Cervical cancer prevention in the era of prophylactic vaccines, a preview for gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:552–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dames DN, Blackman Elizabeth, Butler Raleigh, Taioli Emanuela, Eckstein Stacy, Devarajan Karthik. High-risk cervical human papillomavirus infections among human immunodeficiency virus-positive women in the Bahamas. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn ML, Schuurhuis DH, Vierboom MP, Vermeulen H, de Cock KA, Ooms ME, Ressing ME, Toebes M, Franken KL, Drijfhout JW, Ottenhoff TH, Offringa R, Melief CJ. Immunization with human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) oncoprotein-loaded dendritic cells as well as protein in adjuvant induces MHC class I-restricted protection to HPV16-induced tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:724–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813–819. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiben GL, Velders MP, Kast WM. The cell-mediated immune response to human papillomavirus-induced cervical cancer, implications for immunotherapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2002;86:113–148. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(02)86004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltkamp MC, Smits HL, Vierboom MP, Minnaar RP, de Jongh BM, Drijfhout JW, ter Schegget J, Melief CJ, Kast WM. Vaccination with cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-containing peptide protects against a tumor induced by human papillomavirus type 16-transformed cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2242–2249. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife KH, Wheeler CM, Koutsky LA, Barr E, Brown DR, Schiff MA, Kiviat NB, Jansen KU, Barber H, Smith JF, Tadesse A, Giacoletti K, Smith PR, Suhr G, Johnson DA. Dose-ranging studies of the safety and immunogenicity of human papillomavirus Type 11 and Type 16 virus-like particle candidate vaccines in young healthy women. Vaccine. 2004;22:2943–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankild S, de Boer RJ, Lund O, Nielsen M, Kesmir C. Amino acid similarity accounts for T cell cross-reactivity and for “holes” in the T cell repertoire. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Singh A, Srivastava M, Gupta SK, Akhoon BA. In silico DNA vaccine designing against human papillomavirus (HPV) causing cervical cancer. Vaccine. 2009;28:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Smita S, Sarangi AN, Srivastava M, Akhoon BA, Rahman Q, Gupta SK. In silico CD4 + T-cell epitope prediction and HLA distribution analysis for the potential proteins of Neisseria meningitidis Serogroup B—a clue for vaccine development. Vaccine. 2010;28:7092–7097. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Srivastava M, Akhoon BA, Smita S, Schmitz U, Wolkenhauer O, Vera J, Gupta SK. Identification of immunogenic consensus T-cell epitopes in globally distributed influenza-A H1N1 neuraminidase. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Srivastava M, Akhoon BA, Gupta SK, Grabe N. In silico accelerated identification of structurally conserved CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell epitopes in high-risk HPV types. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan MA, Hossain M, Alam MJ. A computational assay to design an epitope-based Peptide vaccine against saint louis encephalitis virus. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2013;7:347–355. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S13402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S, Henikoff JG. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog TJ, Wright JD. The impact of cervical cancer on quality of life-the components and means for management. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh WK, Roden RB. The future of vaccines for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:S48–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin S, Jores R. In: Theoretical and experimental insights into immunology. Perelson AS, Weisbuch G, editors. Berlin: Springer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Liu TY, Hussein WM, Toth I, Skwarczynski M. Advances in peptide-based human papillomavirus therapeutic vaccines. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12:1581–1592. doi: 10.2174/156802612802652402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;23:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin-Drubin ME. Human papillomaviruses and non-melanoma skin cancer. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:284–290. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer CJ, Heideman DA, Berkhof H, Snijders PJ. Prevention of cervical cancer: where immunology meets diagnostics. Immunol Lett. 2009;122:126–127. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiring TL, Salimo AT, Coetzee B, Maree HJ, Moodley J, Hitzeroth II, Freeborough MJ, Rybicki EP, Williamson AL. Next-generation sequencing of cervical DNA detects human papillomavirus types not detected by commercial kits. Virol J. 2012;9:164. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:518–527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oany AR, Emran AA, Jyoti TP. Design of an epitope-based peptide vaccine against spike protein of human coronavirus: an in silico approach. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;21:1139–1149. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S67861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandhi D, Sonthalia S. Human papilloma virus vaccines: current scenario. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2011;32:75–85. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.85409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Jr, Hariri S, Chesson H, Curtis CR, Saraiya M, Unger ER, Markowitz LE, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR. 2015;64:300–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova G, Ferrante A, Gorski J. Cross-reactivity of T cells and its role in the immune system. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32:349–372. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i4.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani P, Parkin DM, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from eighteen major cancers in 1985. Implications for prevention and projections of future burden. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:891–903. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanović S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar MM, Gupta SK, Ghorban K, Nabian S, Sazmand A, Taheri M, Esfandyari S, Taheri M. Designing and modeling of complex DNA vaccine based on tropomyosin protein of Boophilus genus tick. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;175:323–339. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1245-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautava J, Syrjänen S. Biology of human papillomavirus infections in head and neck carcinogenesis. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6(1):S3–S15. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reche PA, Reinherz EL. Sequence variability analysis of human class I and class II MHC molecules: functional and structural correlates of amino acid polymorphisms. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:623–641. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roomp K, Antes I, Lengauer T. Predicting MHC class I epitopes in large datasets. BMC Bioinform. 2010;17:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakib MS, Islam MR, Hasan AK, Nabi AH. Prediction of epitope-based peptides for the utility of vaccine development from fusion and glycoprotein of nipah virus using in silico approach. Adv Bioinform. 2014;2014:402492. doi: 10.1155/2014/402492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senapathy JG, Umadevi P, Kannika PS. The present scenario of cervical cancer control and HPV epidemiology in India: an outline. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1107–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon CE (1948) The mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J 27:379–423 and 623–656

- Sharma A, Arya DK, Sagar V, Bergmann R, Chhatwal GS, Johri AK. Identification of potential universal vaccine candidates against group A Streptococcus by using high throughput in silico and proteomics approach. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:336–346. doi: 10.1021/pr3005265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern LJ, Wiley DC. Antigenic peptide binding by class I and class II histocompatibility proteins. Structure. 1994;2:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel I, Berchtold S, Götze A, Schulze U, Schuler G, Steinkasserer A. Human dendritic cells transfected with either RNA or DNA encoding influenza matrix protein M1 differ in their ability to stimulate cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Gene Ther. 2000;7:2028–2035. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumalee S, Supaporn S, Jongkolnee S, Surapan K, Kobkul T, Anusorn B, Chaisuksunt V, Lekawanvijit S, Srisomboon J, Thorner PS. HPV genotyping in cervical cancer in Northern Thailand Adapting the linear array HPV assay for use on paraffin-embedded tissue. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:555–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supindham T, Chariyalertsak S, Utaipat U, Miura T, Ruanpeng D, Chotirosniramit N, Kosashunhanan N, Sugandhavesa P, Saokhieo P, Songsupa R, Siriaunkgul S, Wongthanee A. A high prevalence and genotype diversity of anal HPV infection among MSM in Northern Thailand. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Poveda K, Bahena-Román M, Madrid-González C, Burguete-García AI, Bermúdez-Morales VH, Peralta-Zaragoza O, Madrid-Marina V. Role of IL-10 and TGF-β1 in local immunosuppression in HPV-associated cervical neoplasia. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:753–763. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i4.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdespino V, Gorodezky C, Ortiz V, Kaufmann AM, Roman-Basaure E, Vazquez A, Berumen J. HPV16-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses are detected in all HPV16-positive cervical cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wain G. The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, HPV related diseases and cervical cancer in the post-reproductive years. Maturitas. 2010;65:205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.