Abstract

Long gaps between active replication origins probably occur frequently during chromosome replication, but little is known about how cells cope with them. To address this issue, we deleted replication origins from S. cerevisiae chromosome III to create chromosomes with long interorigin gaps and identified mutations that destabilize them [originless fragment maintenance (Ofm) mutations]. ofm6-1 is an allele of HST3, a sirtuin that deacetylates histone H3K56Ac. Hst3p and Hst4p are closely related, but hst4Δ does not cause an Ofm phenotype. Expressing HST4 under the control of the HST3 promoter suppressed the Ofm phenotype of hst3Δ, indicating Hst4p, when expressed at the appropriate levels and/or at the correct time, can fully substitute for Hst3p in maintenance of ORIΔ chromosomes. H3K56Ac is the Hst3p substrate critical for chromosome maintenance. H3K56Ac-containing nucleosomes are preferentially assembled into chromatin behind replication forks. Deletion of the H3K56 acetylase and downstream chromatin assembly factors suppressed the Ofm phenotype of hst3, indicating that persistence of H3K56Ac-containing chromatin is deleterious for the maintenance of ORIΔ chromosomes, and experiments with synchronous cultures showed that it is replication of H3K56Ac-containing chromatin that causes chromosome loss. This work shows that while normal chromosomes can tolerate hyperacetylation of H3K56Ac, deacetylation of histone H3K56Ac by Hst3p is required for stable maintenance of a chromosome with a long interorigin gap. The Ofm phenotype is the first report of a chromosome instability phenotype of an hst3 single mutant.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00438-015-1105-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: SNP analysis, Genome stability, DNA replication, Histone H3 K56 acetylation, Sirtuin

Introduction

The long, linear DNA molecules of eukaryotic chromosomes are replicated from multiple replication origins. In most eukaryotes, replication origins are inefficient, initiating replication in fewer than 30 % of cell cycles (Tuduri et al. 2010). Although regions of chromosomes replicate during reproducible times during S phase, initiation at individual origins is thought to be stochastic (Bechhoefer and Rhind 2012). These factors lead to the presence of long gaps between some active replication origins in most S phases. It is not known how cells cope with these long interorigin gaps. We created a derivative of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome III from which we deleted the five most active replication origins (the 174-kb 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment, see schematic diagram in Fig. 1), creating a long interorigin gap (Dershowitz et al. 2007). Even though the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment is duplicated and segregated properly in >99 % of cell divisions, it is sensitive to subtle perturbations in DNA replication, checkpoint surveillance, and chromatin structure (Theis et al. 2010). This sensitivity is likely created because replication initiates infrequently on this chromosome, causing replication forks to traverse much longer distances than normal. The maximum gap between origins mapped in S. cerevisiae is 90 kb, significantly below the gap size predicted for randomly distributed origins in intergenic regions. This finding suggests that the origin distribution has been at least in part determined to reduce the interorigin gaps to minimize the consequences of irreversible fork stalling (Newman et al. 2013). The ORI-deletion chromosome, creating a long unnatural gap between known origins, is a unique tool for uncovering pathways contributing to chromosome stability because the problems causing instability of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment are likely to be experienced by wild-type chromosomes during the course of normal DNA replication when adjacent replication origins fail to initiate or converging forks stall between adjacent origins. To elucidate the mechanism(s) responsible for maintenance of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment, we identified mutants that selectively destabilized it, but had little or no effect on the stability of the 0ORIΔ-ΔR fragment, which we named originless fragment maintenance (Ofm) mutants (Theis et al. 2007). In the study reported here, we demonstrate that ofm6-1 is an allele of HST3, and show that the persistence during S phase of the acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 normally removed by Hst3p and Hstp4 causes chromosome loss, likely by inhibition of replication fork movement.

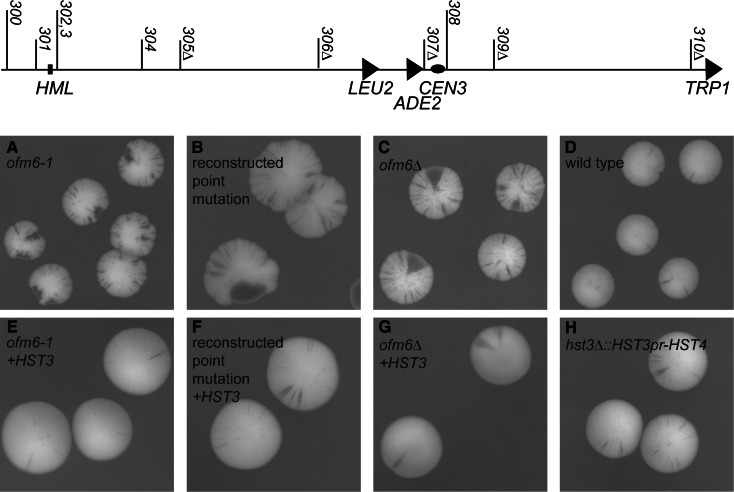

Fig. 1.

Ofm phenotype and complementation test. A schematic drawing of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment of chromosome III is shown at the top. The positions of ARS elements are indicated by numbers above the line, with three digit numbers (e.g., 301) indicating dormant origins still present on the fragment and three digit numbers followed by a “triangle” symbol (e.g., 305Δ) indicating origin deletions. The arrows on the line represent the three selectable markers LEU2, ADE2 and TRP1; the latter marks the position of the chromosome fragmentation that removed the right arm of the chromosome distal to the ARS310 deletion. This fragment was introduced into both the wild-type (YKN15) and the ofm6-1 mutant (YJT417) by chromoduction. After selection, chromoductants were plated for single colonies on medium containing limiting adenine, and incubated for 5 days at 30 °C. Panels a, b and c show colonies from three different hst3 strains: the original ofm6-1 isolate (YJT417), the reconstructed point mutant (YIC257) and the hst3Δ::kanMX mutant (YIC247), respectively. Panel d shows colony-sectoring phenotypes of the wild-type strain. Loss events are visualized as red sectors in white colonies. A complementation test was done by introducing the HST3 gene into each of these mutants. A plasmid carrying the HST3 ORF under the control of its own promoter was integrated into the non-essential YGL119 W ORF by two-step gene replacement. Note that the HST3 gene complements the colony-sectoring phenotype of all mutants: e ofm6-1 (YIC275) f reconstructed point mutant (YIC271) and g hst3Δ (YIC273). Panel d shows the colony-sectoring phenotypes of a strain carrying the HST4 ORF integrated in the HST3 locus so that HST4 expression is regulated by the HST3 promoter plus the 3′ UTR (hst3::HST3pr-HST4)

Hst3p is a histone deacetylase (HDAC) that, together with the related HDAC encoded by HST4, removes acetyl groups from lysine 56 (K56) in the core domain of histone H3 (Celic et al. 2006; Maas et al. 2006). Hst3p and Hst4p belong to the family of NAD+-dependent HDACs called sirtuins, which are found in virtually all organisms. Budding yeast contain five sirtuins, Hst1p through Hst4p, and Sir2p, the founding member of the family (Brachmann et al. 1995). HST3 and HST4 have been implicated in maintenance of genome integrity in S. cerevisiae by the observation that simultaneous deletion of HST3 and HST4 causes defects in cell cycle progression, chromosome loss, spontaneous DNA damage, including gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs), base substitutions, small insertions and deletions, as well as acute sensitivity to genotoxic agents, and thermosensitivity. These phenotypes are all caused by constitutive H3 K56 acetylation (Celic et al. 2006; Kadyrova et al. 2013; Maas et al. 2006).

HST3 is controlled both at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. The protein is targeted for degradation after the phosphorylation of a multisite degron, and its turnover is increased in response to replication stress in a RAD53-dependent manner (Delgoshaie et al. 2014; Edenberg et al. 2014).

Histone proteins form the cores of nucleosomes, the fundamental units of chromatin. They undergo a variety of posttranslational modifications including phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation and acetylation. These modifications regulate several aspects of chromosome dynamics. Acetylation, in particular, occurs both on newly synthesized histone proteins, where it regulates nucleosome assembly and DNA repair, and on nucleosome-incorporated histones, where it regulates chromatin condensation, heterochromatin silencing and gene expression (reviewed by Shahbazian and Grunstein 2007). Acetyl groups are added to ε-amino groups of lysines by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and removed by HDACs.

Acetylation was first observed within the N-terminal tails of the four histone proteins (Shahbazian and Grunstein 2007). However, at least two acetylation sites within the core domains of histones H3 and H4, lysine 56 in histone H3 (H3 K56) (Hyland et al. 2005; Masumoto et al. 2005; Ozdemir et al. 2005) and lysine 91 in histone H4 (Ye et al. 2005) are known. H3 K56 acetylation is found in Drosophila, mouse, rat and human cells (Das et al. 2009; Tjeertes et al. 2009; Xie et al. 2009; Yuan et al. 2009).

In S. cerevisiae, H3K56 acetylation occurs on newly synthesized H3 before its incorporation into chromatin by both replication-coupled and replication-independent mechanisms and is removed from nucleosomes during G2 and M phases (Masumoto et al. 2005). The H3K56Ac modification increases the efficiency of nucleosome assembly on DNA by increasing the binding affinities of the CAF-1 and Rtt106p chromatin assembly factors for histone H3 during DNA replication (Li et al. 2008), and is also important for the replication-independent turnover of nucleosomes (Kaplan et al. 2008).

A gene interaction analysis showed that HST3 interacts with genes of an epistasis group that promotes genome stability and with deletions that perturb DNA replication. The hst3 mutation showed positive genetic interactions with members of this epistasis group, including asf1Δ, rtt109Δ, rtt101Δ, mms1Δ and mms22Δ (Collins et al. 2007; Pan et al. 2006). The RTT109-encoded acetyltransferase is the predominant HAT for H3 K56 (Driscoll et al. 2007; Han et al. 2007; Tsubota et al. 2007). Rtt109p has been shown to form separate complexes with two histone chaperones Vps75p and Asf1p. ASF1 deletion, but not VPS75 deletion, completely abolishes H3 K56 acetylation in vivo (Tsubota et al. 2007). Rtt101p is a cullin that assembles a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that preferentially binds and ubiquitinates histone H3 acetylated on lysine 56. Mms1p and Mms22p are adaptor proteins for substrate binding. Moreover, this ubiquitination weakens the Asf1 and H3–H4 interaction facilitating the transfer of the histone heterodimer to other histone chaperones, CAF-1 and Rtt106p, for nucleosome assembly (Han et al. 2013; Zaidi et al. 2008).

In this study, we found Hst3p in two separate screens for maintenance of originless chromosomes showing a link between chromosome stability—in particular DNA replication progression—and H3 K56 acetylation. Our evidence also showed that, despite difference in amino acid sequence and timing of expression, the closely related homolog HST4 can complement the hst3 mutation. We confirmed that the cycling of the H3K56Ac modification between G2/M and S phase is crucial for proper chromosome maintenance, and that the presence of H3K56Ac ahead of replication forks causes ORI∆ chromosome loss.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. All YKN10 and YKN15 derivatives are isogenic with YPH499 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989); the chromosome fragment donor strains are in the CF4-16B background (Dershowitz et al. 2007); the BY4741-derived strains are related to S288C (Brachmann et al. 1998). The strains used for ofm6-1 linkage analysis were YJT371, harboring the ofm6-1 mutation and BY4741 derivatives, each carrying a kanMX-marked deletion (Table S2). Deletions of both copies of the genes encoding histone H3 and histone H4 were introduced into the YPH499 background by crossing MSY421 (provided by MM Smith, Univ. of Virginia) to YJT3. The sole source of histones H3 and H4 in this hht1Δ hhf1Δ, hht2Δ hhf2Δ strain(YIC335) is the plasmid, pMS329 (HHT1-HHF1-CEN4-URA3) (Megee et al. 1990). Several strains were constructed by introducing PCR products carrying kanMX-marked deletions amplified from the Open Biosystems systematic deletion collection by transformation. 5ORIΔ-ΔR and 0ORIΔ-ΔR fragments were introduced into yeast strains by chromoduction as described by Theis et al. (2007).

Plasmids constructed for this study include the ofm6-1 point mutation rescue plasmid, the HST3::URA3 plasmid used for integration of HST3 into the intergenic region adjacent to the YGL119 W ORF, the hst3Δ::HST3pr-HST4 construct used for expressing Hst4p under the control of Hst3p regulatory sequences, and the TRP1 CEN6 plasmids expressing the histone H3 K56R and K56Q alleles used in plasmid shuffle experiments. Details of constructs are available upon request.

Loss rate determinations

Fluctuation analyses were performed as described previously (Dershowitz and Newlon 1993). For the half-sectored colony assay, cells were plated on color assay medium and incubated for 5 days at 30 °C. Approximately 1000 total colonies were analyzed for each time point. Loss rates were calculated as the fraction of half-sectored colonies obtained in at least 4 independent experiments.

Cell synchronization and FACS analysis

MATa cells (1 × 107cells/ml) were incubated for 3 h at 25 °C with 5–10 nM Nle-12 α-factor (Raths et al. 1988) (a gift from F. Naider, College of Staten Island, The City Univ. of New York), then released from G1 arrest by washing out α-factor and transferring the cell suspension to fresh YPD containing 0.1 mg/ml protease (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell cycle progression was monitored by Flow Cytometry with a LSR II four laser bench top Immunocytometry System (BD Biosciences) as described (Paulovich and Hartwell 1995).

Microarray analysis

The Affymetrix GeneChip®S. cerevisiae Tiling 1.0R Array was used in this study. The probes on the array are 25-mer oligonucleotides tiled at an average resolution of 5 base pairs. This array design was previously used to locate SNPs and deletion breakpoints in the yeast genome (Gresham et al. 2006). DNA was isolated using QIAGEN Genomic-tip 500G according to the manufacturers protocol. DNA (10 μg) was digested to 50-bp fragments using 1U of DNase I (Amersham) and end-labeled with biotin using the GeneChip Double-Stranded DNA Terminal Labeling kit (Affymetrix). The biotin-labeled DNA was hybridized to the array for 16 h at 45 °C using a GeneChip Hybridization Oven 640. Washing and staining with Streptavidin–phycoerythrin were performed using the GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 and the FS450_0001 Fluidics Protocol. Images were acquired using the Affymetrix Scanner 3000 7G. The microarray data were analyzed using the SNPScanner algorithm as previously described (Gresham et al. 2006). We detected mutations in the mutant strain by comparing SNPs detected in the ofm6-1 strain with SNPs detected in the isogenic wild-type strain. This was necessary as the wild-type strain used in this study differed substantially in sequence content from the S288C reference genome. We employed the identical heuristic cutoffs used to minimize false-positive SNP detection as described by Gresham et al. (2006).

Analysis of replication intermediates

Analysis was performed as previously described (Theis and Newlon 2001).

Results

Classical genetic and genome-wide approaches to identify the ofm6-1 mutation

Our initial goal in this study was to identify the gene harboring the recessive ofm6-1 mutation (Theis et al. 2007). Ofm mutations were identified using a visual screen based on colony sectoring. The strains used for these screens are partially disomic for chromosome III, carrying a wild-type balancer chromosome III and the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment of chromosome III (Dershowitz et al. 2007), introduced by chromoduction (Ji et al. 1993). This chromosome fragment is genetically marked in a way that allows both its selection and the visualization of its loss in a colony-sectoring assay. Losses of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment are visualized as red sectors in a white colony (Fig. 1).

We could not use the classical approach of complementation with a wild-type plasmid library to identify the mutation because, as we learned in our attempt to complement the ofm14-1 mutation, the frequency of missegregation of the fragment, which produces white, non-sectoring colonies, was much greater than the probability of finding a complementing plasmid (Theis et al. 2007). Moreover, the ofm6-1 strain was insensitive to UV and to several drugs [methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), hydroxyurea (HU), phleomycin and camptothecin] tested to identify a secondary phenotype for complementation; therefore, we pursued a different strategy. We searched genome wide for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), using a high-density Affymetrix yeast tiling microarray (Gresham et al. 2006). The ofm6-1 mutant was compared to its wild-type parent, YKN10, to reveal SNPs unique to the ofm6-1 mutant. A total of 244 candidate SNPs were identified in the mutant and were distributed as follows: 142 in ORFs, 43 in intergenic regions, 48 in repeated sequences (retrotransposons, Y′ elements, long terminal repeats, rDNA, ARS elements and telomeres) and 11 in introns and dubious ORFs.

Classical genetic mapping allowed us to reduce the number of candidate mutations that could account for the ofm6-1 phenotype, as crosses to strains carrying mutations in genes involved in DNA replication revealed that ofm6-1 is on chromosome XV (Table S2).

From our screen of the S. cerevisiae viable deletion collection for new Ofm mutants (Theis et al. 2010), we knew that strains carrying deletions of three adjacent ORFs near CEN15, YOR024 W, HST3 and BUB3 showed a colony-sectoring phenotype. In the microarray analysis, we found that a SNP mapped at chromosome XV coordinate 378826, which is located in the HST3 ORF (Figure S1), moreover, there were no SNPs in either BUB3 or YOR024 W in the ofm6-1 mutant strain (Figure S2). Nucleotide sequence analysis of the HST3 gene recovered from the ofm6-1 strain confirmed the presence of the predicted SNP, which changes the Trp206 codon (UGG) into a stop codon (UAG).

ofm6-1 is an allele of HST3

To confirm that ofm6-1 is an allele of HST3, we reconstructed the point mutation in a wild-type strain. This strain had a phenotype indistinguishable from that of the original ofm6-1 mutant (Fig. 1a, b), confirming that the mutation identified in hst3 caused the sectoring phenotype in the ofm6-1 mutant.

We also moved the hst3Δ::kanMX deletion into the wild-type YKN15 strain background by one-step gene replacement. The resulting strain showed a colony-sectoring phenotype and a loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment (1.2 ± 0.3 × 10−2) comparable to the original ofm6-1 mutant (Theis et al. 2007), confirming the strong Ofm phenotype observed in the SGA strain background (Fig. 1c). We showed that the HST3 wild-type gene, either on a plasmid or integrated into an ectopic locus in the genome, complemented ofm6-1, the reconstituted point mutant, and the ORF deletion (Fig. 1d–f). Finally, we found elevated H3K56Ac levels persisting in the G2 phase of the cell cycle in both ofm6-1 and hst3Δ mutants (Figure S3), as others have previously shown (Celic et al. 2006).

Although the hst4Δ mutation alone does not cause an Ofm phenotype (data not shown), we were unable to isolate hst3Δhst4Δ double mutant chromoductants carrying the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment, suggesting that Hst4p also contributes to maintenance of this fragment.

Hst4p can substitute for Hst3p

HST3 and HST4 sequences are 26 % identical and 42 % similar overall, with 40 % identity in the core deacetylase domain (Brachmann et al. 1995). Hst3p differs from Hst4p in having a C-terminal extension of 107 amino acids. Expression patterns of Hst3p and Hst4p also differ, with maximal Hst3p expression occurring during G2/M and maximal Hst4p expression during M/G1 (Maas et al. 2006). To determine whether differences between Hst3p and Hst4p proteins or differences in their expression profiles account for the observation that hst3 mutations, but not hst4 mutations cause an Ofm phenotype, we tested whether the HST4 ORF could complement the hst3 colony-sectoring phenotype when placed under the control of HST3 regulatory sequences by constructing strains in which Hst4p is expressed under control of both its normal regulatory sequences at its endogenous locus and the HST3 upstream and downstream regulatory elements at the HST3 locus. Four independent strains carrying the ORF swap showed a colony-sectoring phenotype comparable to a wild-type strain, indicating that expression of HST4 from the HST3 locus complements the hst3Δ colony-sectoring phenotype (Fig. 1d, h). We conclude that the two proteins are interchangeable and that Hst4p can fully substitute for its homolog Hst3p in the maintenance of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment. This result indicates that either the timing or level of expression of Hst3p is responsible for its predominant role in 5ORIΔ-ΔR chromosome maintenance, not its differences in amino acid sequence from Hst4p.

Role of the RTT109-MMS22 acetylation pathway in the maintenance 5ORIΔ-ΔR chromosome

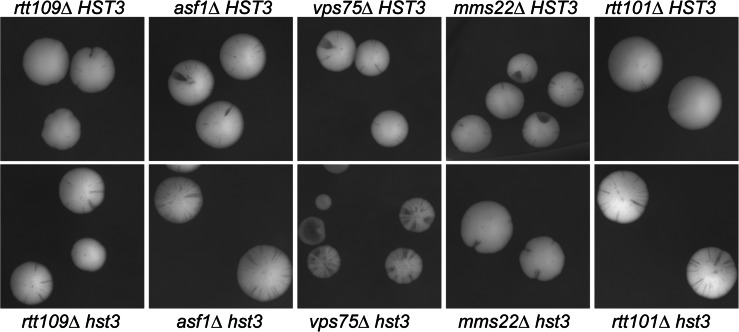

To address a possible role for the RTT109-MMS22 pathway (Collins et al. 2007) in 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment maintenance, we determined the colony-sectoring phenotype of strains carrying deletions of genes in this pathway, both singly and in combination with an hst3 allele. Analysis of the colony-sectoring phenotype showed that none of the single mutations tested caused an increase in the loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment (Fig. 2). However, deletion of ASF1 or RTT109, which are both required to acetylate H3K56, suppressed the colony-sectoring phenotype of hst3 strains, while deletion of VPS75, which encodes another histone chaperone that interacts with Rtt109p, did not.

Fig. 2.

Deletion of components of the Rtt109p acetylation pathway suppresses the hst3 colony-sectoring phenotype. The panels show colony-sectoring phenotypes of strains carrying rtt109Δ, asf1Δ, vps75Δ, mms22Δ and rtt101Δ in both HST3 (top panels strains YIC263, YIC290, YIC302, YIC304, YIC266) and hst3 strains (bottom panels strains YIC260, YIC296, YIC301, YIC306, YIC264)

Rtt101p, Mms1p and Mms22p form a complex that preferentially ubiquitinates K56-acetylated histone H3, which facilitates the incorporation of H3K65Ac-containing nucleosomes into chromatin behind the replication fork. Deletion of RTT101 or MMS1 decreases the amount of H3K56Ac in chromatin (Han et al. 2013). Deletion of either RTT101 or MMS22 suppressed the hst3 phenotype, suggesting that the persistence of H3K56Ac in chromatin causes the Ofm phenotype.

While others have shown that lack of Rtt101 suppresses the temperature- and DNA damage-sensitive phenotypes of the double hst3hst4 mutant, we directly evaluated a chromosome loss phenotype to show that the same suppression occurs in the hst3 mutant.

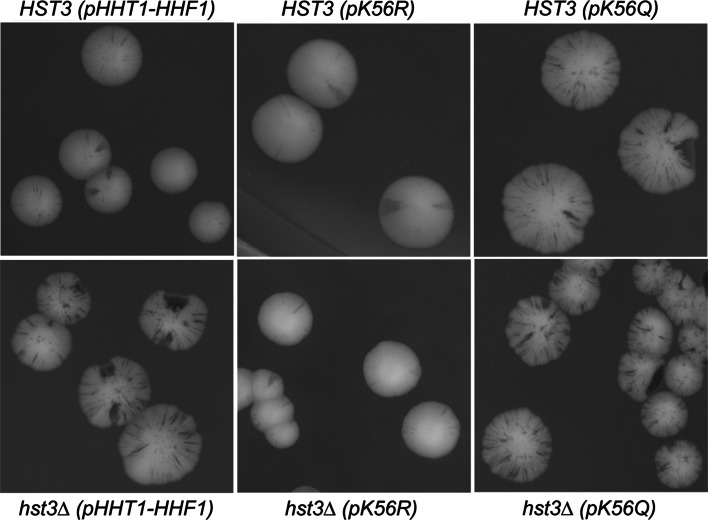

H3K56Ac is the Hst3p substrate critical for 5ORIΔ-ΔR chromosome maintenance

The fact that rtt109, asf1, rtt101 and mms22 deletions suppressed the hst3 sectoring phenotype suggests that H3K56Ac is a relevant Hst3p substrate for 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment maintenance. However, it is possible that acetylation of a different, as yet unknown, Rtt109p target contributes to this phenotype. To directly test the relevance of H3 K56 deacetylation in 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment stability, we constructed a set of yeast strains expressing derivatives of histone H3 in which K56 was changed either to glutamine (K56Q) or arginine (K56R) as the sole source of histone H3, and then we followed 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment stability by monitoring the colony-sectoring phenotype in both HST3 and hst3Δ strains. If H3K56Ac is the critical Hst3p substrate for 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment stability, then the strains expressing only H3K56Q, which mimics constitutive acetylation, should recapitulate the hst3Δ Ofm phenotype in the HST3 strain. In addition, H3K56Q expression should not exacerbate the hst3 phenotype, because H3 K56Q mimics constitutive acetylation. On the other hand, the instability of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment should be suppressed in hst3 strains expressing only H3 K56R, which cannot be acetylated. In addition, the phenotype of the HST3 strain should not be affected by this substitution, because we have shown that rtt109Δ strains, which lack the HAT, do not exhibit an elevated colony-sectoring phenotype (Fig. 2). The results validated the expectations. Only the plasmid expressing H3 K56Q caused a strong colony-sectoring phenotype in an HST3 strain (Fig. 3b). Similarly, strong sectoring phenotypes were apparent in hst3Δ transformants expressing either the wild-type histone H3 or the H3 K56Q allele (Fig. 3d, e). Expression of the K56R allele suppressed the colony-sectoring phenotype of the hst3Δ strain, but it had no effect in a wild-type HST3 strain (Fig. 3c, f). These results indicate that Hst3p deacetylation of H3K56Ac is crucial for 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment stability. They also exclude mechanisms dependent on other deacetylase target(s) or deacetylase-independent activities of Hst3p.

Fig. 3.

H3K56Ac is the critical target of HST3 deacetylase. All the strains shown carry deletions of both copies of the genes encoding histones H3 and H4 (hht1Δ-hhf1Δ and hht2Δ-hhf2Δ). The sole source of histones H3 and H4 in these strains is a plasmid carrying wild-type histone genes pHHT1-HHF1 (strains YIC335, YIC349), a plasmid carrying an H3 K56R substitution phht2K56R-HHF2 (YIC339, YIC351), or a plasmid carrying an H3 K56Q substitution phht2K56Q-HHF2 (YIC345, YIC350). The top row shows colonies of a wild-type HST3 strain transformed with each of the plasmids. The bottom row shows colonies of the hst3Δ strains transformed with each of the plasmids

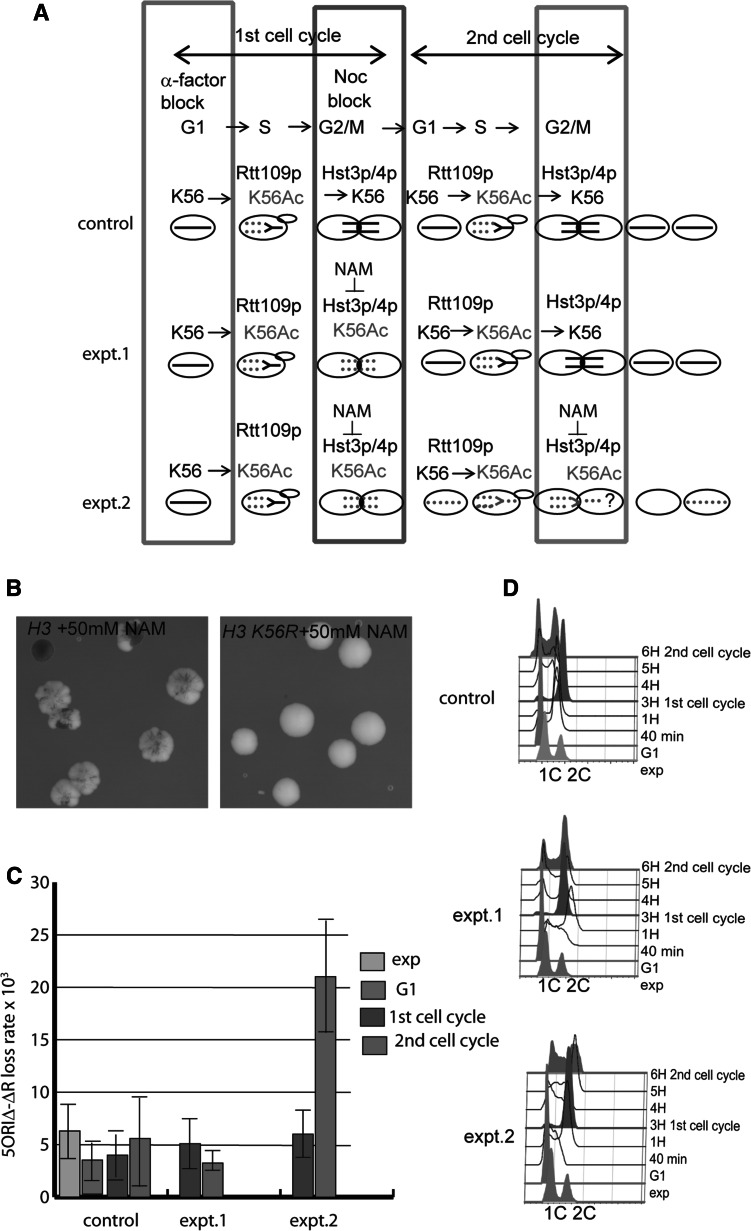

The presence of H3K56Ac in the second cell cycle following inhibition of sirtuins causes 5ORIΔ-ΔR chromosome destabilization

To determine at what point in the cell cycle failure to deacylate H3K56Ac causes the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment to become unstable, we made use of a potent non-competitive sirtuin inhibitor, nicotinamide (NAM) (Bitterman et al. 2002), to temporarily inactivate sirtuins, including Hst3p and Hst4p, in a wild-type strain. We found that 50 mM NAM is sufficient to destabilize the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in an HST3 background (Fig. 4b), and that it causes H3 K56 hyperacetylation levels comparable to hst3Δ mutants, as shown by Western blotting using a specific anti-H3K56Ac antibody (Figure S3). Moreover, we showed that 50 mM NAM did not cause increased sectoring in the strain expressing H3K56R as the sole source of histone H3, demonstrating that Hst3p and Hst4p are the crucial targets of NAM inhibition in 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment maintenance (Fig. 4b). This finding is consistent with the observation that Hst3p and Hst4p are the HDACs for H3K56Ac and that other single or multiple sirtuin deletions do not affect H3K56Ac levels (Celic et al. 2006).

Fig. 4.

H3 K56 Hyperacetylation and DNA replication. a The top row shows an outline of the experiment with arrows indicating progression to consecutive steps of the cell cycle, G1, S and G2/M. This experiment was done with a HST3 strain (YKN15). The three schematic drawings below represent the H3 K56 acetylation patterns expected in the three experimental conditions tested. A single chromosome is shown as an example. Solid black lines indicate chromatin with non-acetylated H3 K56; dotted red lines indicate chromatin with acetylated H3 K56. Colored boxes indicate the points at which samples were taken for plating (Panel c) and FACS analysis (Panel d). In the control experiment, H3 K56 is acetylated by Rtt109p and incorporated into chromatin during S phase; the H3 K56 acetyl groups are removed by Hst3p and Hst4p activity in G2, M and the following G1 so chromosomes begin the second cell cycle with unacetylated H3 K56 in chromatin. In experimental condition #1 the NAM treatment was present during the first cell division and removed when cells were released from nocodazole. The results suggest that H3 K56 was deacetylated before entry into the second S phase. In experimental condition #2 NAM was present for the whole time course. b Effect of 50 mM NAM on a strain carrying wild-type histone H3 genes (YJT503) and a strain expressing an H3 K56R substitution (YIC339) as the sole source of histone H3. c 5ORIΔ-ΔR loss rate determined as the fraction of half-sectored colonies. Cells in the control culture were synchronized with α-factor, then released into medium containing nocodazole and incubated for 3 h. Samples were collected from the exponentially growing culture (exp), at the α-factor block (G1), at the nocodazole block (1st cell cycle) and 3 h after nocodazole release (2nd cell cycle). The two experimental cultures were released from the α-factor block into medium containing nocodazole +50 mM NAM for 3 h (1st cell cycle). The nocodazole block was removed by washing the cells and resuspending them in YPD (expt. #1) or YPD containing 50 mM NAM (expt. #2); samples were collected after 3 h (2nd cell cycle). Samples from each time point were diluted and plated. Plates were incubated for 5 days at 30 °C and scored for half-sectored colonies. Loss rates were calculated as the fraction of half-sectored colonies. The graph shows mean ± SD, calculated from at least 4 different replicas. d FACS analysis

We followed cells treated with NAM during two consecutive cell cycles, and monitored the loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment as the proportion of half-sectored colonies, which result from chromosome loss events occurring in the first division of a cell that forms a colony. In control experiment, we showed that neither α-factor synchronization nor nocodazole treatment caused instability of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment relative to the untreated culture (Fig. 4c, control).

In the experimental cultures, we expected to see no increase in the loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment during the first cell division following treatment with NAM because cells accumulate H3K56Ac only in newly assembled chromatin behind the replication fork. However, we expected a dramatic increase in the loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment during the second cell division, because cells had to replicate chromatin marked with H3 K56Ac during the second S phase. Indeed that was the result (Fig. 4).

Experimental cultures were treated with NAM either for the 1st cell cycle (expt. 1) or both 1st and 2nd cell cycle (expt. 2). We expected to see an increase in loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in the second division of both experimental conditions; however, only when cultures were left in the presence of NAM during both cell cycles did they show a significant increase in the loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment 2.1 ± 0.5 × 10−2 (Fig. 4c, experiment 2). A likely explanation is that expression of Hst4p as cells recovered from the nocodazole block and during the subsequent G1 (Maas et al. 2006) allowed deacetylation of H3 K56Ac in the absence of NAM in experiment 1. Overall, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that H3K56Ac is detrimental for the maintenance of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment only when cells enter S phase in the presence of H3K56Ac-containing chromatin, and indicate that is replication of H3K56Ac-containing chromatin that causes chromosome loss.

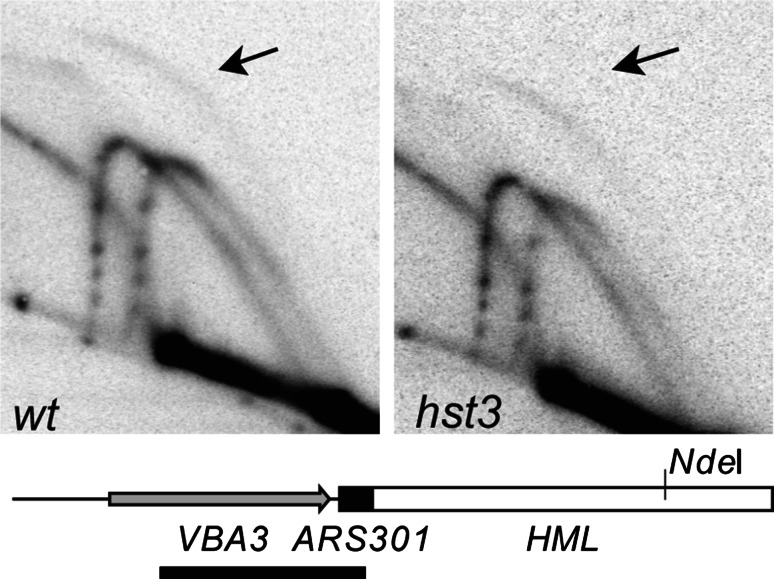

DNA replication initiation is not impaired on the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in the hst3 mutant

Our previous analysis of the stabilities of various ORIΔ derivatives of chromosome III in the ofm6-1 mutant suggested that this hst3 allele causes a fork progression rather than an initiation defect during 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment replication (Theis et al. 2007). We showed that initiation at efficient replicators, ARS305 and ARS315 on the balancer chromosome III, and ARS1421, was unaffected in the hst3 mutant. Moreover, we could not detect a decrease in mitotic stability of a plasmid carrying multiple ARS elements relative to a plasmid a single copy of ARS1 indicating that replication initiation at ARS1 is not affected. We used a restriction-site polymorphism present near ARS301 to distinguish the replication intermediates arising from ARS301 on the balancer chromosome III from those arising from ARS301 on the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment. We found bubble-shaped intermediates arising from the fragment but not from the balancer chromosome III, indicating that ARS301 fires only in the 5ORIΔ-ΔR chromosome (Theis et al. 2007). However, we had not tested the possibility that activation of the dormant origins, still present on the left arm of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment, is defective in an hst3 strain. To this end, we tested ARS301 activity on the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in the hst3 mutant (Fig. 5). The presence of bubble-shaped intermediates in the pattern arising from the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment and not in the pattern from the balancer chromosome III confirmed that DNA replication initiates at ARS301 on the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in both hst3Δ and HST3 strains. To compare the relative intensities of the bubble arcs in the pattern from HST3 and hst3Δ strains, we calculated the ratio of signal in the bubble arc to signal in the ascending portion of the Y-arc produced by the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in each strain. In the gel in Fig. 5, the ratio was 0.52 in the wild-type HST3 strain and 0.9 in the hst3Δ mutant. In a second experiment, we obtained similar values, 0.75 in the wild-type HST3 strain and 0.62 in the hst3Δ mutant. We conclude that initiation at the dormant origins present on the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment is not defective in the hst3Δ strain. Together with our previous analysis of efficient origins, these data indicate that replication initiation at the canonical ARS elements analyzed is not affected by the hst3Δ mutation, although the 2D gel technique we used may not be sensitive enough to detect a subtle defect. We conclude that hst3∆ primarily causes a fork progression defect. We cannot rule out the possibility that this fork progression defect represents a failure to activate dormant origins that have not been identified by the canonical ARS assay yet would rescue the replication of natural chromosomes in the case of double fork-stall events.

Fig. 5.

Activity of dormant origin ARS301 in hst3 mutant. Genomic DNA was prepared from hst3Δ (YIC281) and wild-type (YJT503) strains. After NdeI digestion, replication intermediates were separated by 2D electrophoresis, blotted and probed with a fragment containing VBA3 and ARS301, indicated by the black bar below the diagram of the NdeI fragment containing ARS301. The fragment from the balancer chromosome III is 4.8 kb; the extra NdeI site present on the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment shortens the ARS301 fragment to 4.1 kb. The ARS301 probe also hybridized to a 7.1-kb NdeI fragment on chromosome XI containing the VBA5 gene. The arrows point to the bubble-shaped intermediates arising from the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment

Discussion

This work showed that the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase encoded by HST3 plays an important role in maintenance of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment of S. cerevisiae chromosome III. These results suggest that Hst3p is important for the replication of wild-type chromosomes that have long gaps between replication origins that result from stochastic initiation events. While others have shown the production of gross chromosomal rearrangements and other spontaneous mutations in hst3hst4 double mutants, we explored more directly how DNA replication is affected in hst3 mutants and we established a link between replication of a long interorigin gap and H3 K56 acetylation.

Identification of ofm6-1 as an allele of HST3 required a combination of approaches: a genome-wide analysis of SNPs present in the mutant and not in the wild-type parent, a genome-wide screening of the yeast viable deletion collection for new Ofm mutants (Theis et al. 2010) and classical genetic analysis. Using these approaches, we identified a single base-pair change that creates a nonsense codon in the HST3 open reading frame as the ofm6-1 mutation. The Ofm phenotype is the first report of a chromosome instability phenotype of an hst3 single mutant.

We showed, for the first time, that despite substantial difference in amino acid sequence and likely differences in the regulation of protein stability (Delgoshaie et al. 2014; Edenberg et al. 2014), Hst4p could fully substitute for HST3p when expressed under the HST3 promoter. This result indicates that either the timing or level of expression of Hst3p is important for 5ORIΔ-ΔR chromosome maintenance, not differences in amino acid sequence between Hst3p and Hst4p.

Moreover, using strains expressing derivatives of histone H3 in which K56 was changed either to glutamine (K56Q) or arginine (K56R) as the sole source of histone H3, and then following 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment stability in both HST3 and hst3Δ strains we showed that H3K56Ac is the Hst3p substrate critical for chromosome maintenance.

It has been shown that H3K56 acetyl groups are transiently present in chromatin, being incorporated in new nucleosomes following the passage of the replication fork and removed prior to the next S phase (Masumoto et al. 2005). The removal of acetyl groups on H3K56 is important because constitutive H3 K56 hyperacetylation, as in the hst3Δ hst4Δ double mutant, causes defects in cell cycle progression, increased chromosome loss, increased spontaneous DNA damage, acute sensitivity to genotoxic agents, and thermosensitivity (Celic et al. 2006; Maas et al. 2006; Thaminy et al. 2007). Following cells during two consecutive cell cycles and monitoring the chromosome loss in the presence of NAM, a non-competitive sirtuin inhibitor, we showed a dramatic increase in the loss rate of the 5ORIΔ-fragment during the second cell division. These data confirm the importance of removing the H3K56Ac mark from chromatin before cells enter into the following cell cycle, as it appears that the presence of H3K56Ac on chromatin when cells enter S phase is detrimental for chromosome maintenance.

We confirmed that components of the H3 K56 acetylation pathway are involved in chromosome maintenance as shown by our findings that deletion of any one of the genes, RTT109, RTT101, MMS22, or ASF1, suppressed the hst3Δ Ofm phenotype. The problems caused by inappropriate H3K56 acetylation in the hst3 mutant can be alleviated in two ways. The first way is preventing H3K56 acetylation, either by deleting the acetyltransferase, Rtt109p, or by deleting the chaperone required for Rtt109p activity, Asf1p. The second way is by preventing H3K56Ac from being incorporated into chromatin by deleting a component of the Rtt101p-Mms1p-Mms22p ubiquitin ligase responsible for releasing the H3K56Ac-H4 histone heterodimer from the Rtt109p/Asf1p complex and transferring it to other chaperones, CAF1 and Rtt106p, for deposition into chromatin (Han et al. 2013; Zaidi et al. 2008).

It is not clear how the acetylation of H3K56 contributes to the chromosome loss phenotype. We propose that, in the absence of Hst3p, which is expressed earlier in the cell cycle and at higher levels than Hst4p (Maas et al. 2006), residual H3K56Ac is left on chromatin after Hst4p is degraded during mitosis, causing chromosomes to enter the next cell cycle with H3K56Ac remaining in their chromatin. The 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment may be particularly vulnerable to retention of this mark because at least a fraction of 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragments are late replicating for two reasons. First, our single molecule analysis of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragments indicates that replication initiates at only one or two places in each molecule in wild-type cells, causing replication forks to traverse longer-than-normal distances, thereby delaying completion of replication (Wang et al. manuscript in preparation). Second, a fraction of 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragments probably initiate replication later than most chromosomes, as we have shown that ‘dormant’ replicators on the left end of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment are activated in about 50 % of the population (Dershowitz et al. 2007), and these replicators appear to be programmed to initiate late (Santocanale et al. 1999). Thus, one explanation for the instability of the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment in hst3 mutants is that in a small fraction of cells the fragment is extremely late replicating and enters the next cell cycle carrying the H3 K56Ac mark; the presence of this mark perturbs the replication of the fragment in the subsequent S phase by causing a replication fork progression defect. While there are almost certainly other late replicating regions of the genome, including the tandem array of rDNA genes (Dulev et al. 2009; Pasero et al. 2002), chromosomes with a normal complement of replicators are less sensitive than the 5ORIΔ-ΔR fragment to the replisome perturbation caused by H3K56Ac because forks from adjacent replicators are available to replicate regions adjacent to stalled or collapsed forks.

A key question is why forks stall and chromosomes are lost when replication forks have to move through chromatin carrying the H3K56Ac mark. Recent work suggests two possibilities. The first is based on the previous observation that abnormal persistence of the H3K56Ac mark affects replisome stability or movement (Celic et al. 2008). Overexpression of RFC1, which encodes a subunit of the complex that loads PCNA, the Polδ and Polε processivity factor, suppresses the temperature‐sensitive growth defect and the sensitivity to genotoxic agents of the hst3 hst4 double mutant. The high levels of H3 K56Ac are not altered in the strains overexpressing RFC1, indicating that increasing the levels of Rfc1p allows cells to survive in the presence of H3 K56 hyperacetylation. Moreover, mutant derivatives of replisome components, including a truncated derivative of DNA Polε encoded by pol2‐11 and epitope‐tagged derivatives of PCNA and Cdc45p that support growth of HST3 HST4 strains, are lethal in combination with hst3Δ hst4Δ, providing further evidence that replisomes are stressed in hst3 hst4 strains. Transient treatment of hst3hst4 strains with low levels of MMS, an alkylating agent that alkylates adenine to 3-methyl adenine, which blocks DNA polymerases, or hydroxyurea, which inhibits ribonucleotide reductase and starves cells for deoxynucleotides for DNA synthesis, causes loss of viability and delays in completion of S phase (Simoneau et al. 2015). Cells activate the DNA damage response (DDR), which normally stabilizes replisomes and delays cell cycle progression (Labib and De Piccoli 2011) and die with incompletely replicated chromosomes, implying that impeding replication during a single S phase is sufficient to kill the double mutant.

Interestingly, deletion of CTF4 suppressed both the temperature sensitivity and HU sensitivity of the hst3Δ hst4Δ double mutant (Celic et al. 2008). Ctf4p functions in both chromosome segregation and DNA replication (Gambus et al. 2006; Lengronne et al. 2006; Spencer et al. 1990). It is a component of the replisome that couples Polα to the MCM helicase on the lagging strand through its interaction with GINS, and the Ctf4 WD40 domain interacts with several fragments of Mms22p in a two-hybrid interaction (Gambus et al. 2006). Replisomes frequently pause at discrete natural pause sites (Ivessa et al. 2003) or sites of DNA damage. Under these conditions of replicative stress, the S phase checkpoint is activated, and the presence of H3K56Ac appears to promote the recruitment of the Rtt101p/Mms1p/Mms22p ubiquitin ligase via the interaction of the Mms22 protein with Ctf4p trimer. Ubiquitination of either Ctf4p or some other component of the replisome results in uncoupling the helicase from Polα, leading to regions of single-stranded DNA and inactivating the replisome (Gambus et al. 2009; Tanaka et al. 2009). If loss of the 5ORI∆ fragment in the hst3 mutant is caused by destabilization of stalled replisomes, we would predict that deletion of ctf4 would suppress the hst3 mutation.

The second possibility is based on the finding that (Simoneau et al. 2015; Wurtele et al. 2012) point mutations in two other histones that reduce levels of H4K14Ac or H3K79Me reduced both the temperature sensitivity and MMS sensitivity of the hst3hst4 double mutant without reducing H3K56Ac levels (Simoneau et al. 2015). These modifications are abundant in yeast chromatin, and deletion of the genes encoding proteins that catalyze these modifications also partially suppressed the phenotypes of the hst3∆hst4∆ mutant. The H3K79Me modification contributes to the activation of the DDR kinase, Rad53p, in the double mutant by recruiting Rad9p to chromatin, where it mediates the activation of Rad53p. A rad9∆ mutation partially suppressed the phenotype of the hst3∆hst4∆ mutant. In contrast to this result, we have found that a rad9∆ causes increased loss of the 5ORI∆ chromosome, and have also argued that DNA damage is unlikely to cause the loss of this chromosome (Theis et al. 2010). Examining the phenotypes expressing H4k14R or H3K79R would provide a further test of this idea.

Overall, the surprising stability of the ORI∆ chromosome shows that even though origin distribution tends to be even throughout the genome to minimize fork collapse, cells can tolerate long interorigin gaps. However, those chromosomes become more sensitive to perturbation of the replication machinery, limiting licensing factors, DNA checkpoints and, as we show proper turnover of histone acetylation.

Electronic supplementary material

Figure S1 Identification of a point mutation in HST3 using tiling microarray data and the SNPScanner algorithm. The likelihood that each nucleotide site is polymorphic, as compared with the S288c reference genome, was computed and compared for wildtype (green) and ofm6-1 mutant (yellow). A mutation was predicted at nucleotide 378,826 (yellow arrow) and confirmed by Sanger sequencing analysis (TIFF 1406 kb)

Figure S2 Unique mutations are not detected in the ofm6-1 mutant (yellow) in BUB3 or IRC12/YOR024W (TIFF 1717 kb)

Figure S3 Panel A Wild type (strain name), ofm6-1, hst3 and cdc15 were synchronized with alpha factor and release into nocodazole. Samples were collected at the alpha factor block (G1 cells), after 40 minutes after the block release (S phase cells) and at the nocodazole block (G2 cells). Cell cycle progression was monitored by FACS. Protein were extracted and run on an SDS-page gel, the blots were probed with both anti-H3 antibody and anti H3 K56 Ac. As expected in the wild type backgrond the H3 K56 acetyl signal is low, almost blank in G1 blocked cells, it gets incorporated during DNA synthesis and removed in G2. In the two hst3 isolates ofm6-1 and hst3Δ the H3K56 Ac signal remain strong in G2, suggesting that the acetyl group is not removed in the mutant. Panel B Wild type (strain name), rtt109Δ and ofm6-1 mutant were synchronized with alpha factor and release into nocodazole with and without nicodinammide. Samples were collected at the alpha factor block (alpha), after 40 minutes after the block release (40 minutes) and at the nocodazole block (100 minutes). Cell cycle progression was monitored by FACS. Treatment of the wild type with NAM causes accumulation of the h3 K56 acetylation in nocodazole blocked cells, suggesting it is recapitulating an hst3 phenotype (TIFF 7341 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Boeke, M.M. Smith and D. Allis for providing plasmids, Dana Stein at the NJMS Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory for assistance with FACS analysis, Tongsheng Wang and Donna Storton for their assistance with the microarray processing, and Ann Dershowitz for fluctuation analysis. We thank also Drs. Michael Newlon, Vivian Bellofatto, Katsunori Sugimoto, Karl Drlica and all the members of the Newlon lab for helpful discussions of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grant GM 35679 to C.S.N.

References

- Bechhoefer J, Rhind N. Replication timing and its emergence from stochastic processes. Trends Genet. 2012;28:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitterman KJ, Anderson RM, Cohen HY, Latorre-Esteves M, Sinclair DA. Inhibition of silencing and accelerated aging by nicotinamide, a putative negative regulator of yeast sir2 and human SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45099–45107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Sherman JM, Devine SE, Cameron EE, Pillus L, Boeke JD. The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2888–2902. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.23.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celic I, Masumoto H, Griffith WP, Meluh P, Cotter RJ, Boeke JD, Verreault A. The sirtuins Hst3p and Hst4p preserve genome integrity by controlling histone H3 lysine 56 deacetylation. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1280–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celic I, Verreault A, Boeke JD. Histone H3 K56 hyperacetylation perturbs replisomes and causes DNA damage. Genetics. 2008;179:1769–1784. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SR, et al. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature. 2007;446:806–810. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature. 2009;459:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature07861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgoshaie N, et al. Regulation of the histone deacetylase Hst3 by cyclin-dependent kinases and the ubiquitin ligase SCFCdc4. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:13186–13196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dershowitz A, Newlon CS. The effect on chromosome stability of deleting replication origins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:391–398. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.1.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dershowitz A, Snyder M, Sbia M, Skurnick JH, Ong LY, Newlon CS. Linear derivatives of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome III can be maintained in the absence of autonomously replicating sequence elements. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4652–4663. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01246-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll R, Hudson A, Jackson SP. Yeast Rtt109 promotes genome stability by acetylating histone H3 on lysine 56. Science. 2007;315:649–652. doi: 10.1126/science.1135862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulev S, de Renty C, Mehta R, Minkov I, Schwob E, Strunnikov A. Essential global role of CDC14 in DNA synthesis revealed by chromosome underreplication unrecognized by checkpoints in cdc14 mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14466–14471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900190106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg ER, Vashisht AA, Topacio BR, Wohlschlegel JA, Toczyski DP. Hst3 is turned over by a replication stress-responsive SCF(Cdc4) phospho-degron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5962–5967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315325111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambus A, Jones RC, Sanchez-Diaz A, Kanemaki M, van Deursen F, Edmondson RD, Labib K. GINS maintains association of Cdc45 with MCM in replisome progression complexes at eukaryotic DNA replication forks. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:358–366. doi: 10.1038/ncb1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambus A, et al. A key role for Ctf4 in coupling the MCM2-7 helicase to DNA polymerase alpha within the eukaryotic replisome. EMBO J. 2009;28:2992–3004. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham D, Ruderfer DM, Pratt SC, Schacherer J, Dunham MJ, Botstein D, Kruglyak L. Genome-wide detection of polymorphisms at nucleotide resolution with a single DNA microarray. Science. 2006;311:1932–1936. doi: 10.1126/science.1123726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhou H, Horazdovsky B, Zhang K, Xu RM, Zhang Z. Rtt109 acetylates histone H3 lysine 56 and functions in DNA replication. Science. 2007;315:653–655. doi: 10.1126/science.1133234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhang H, Zhang H, Wang Z, Zhou H, Zhang Z. A Cul4 E3 ubiquitin ligase regulates histone hand-off during nucleosome assembly. Cell. 2013;155:817–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland EM, Cosgrove MS, Molina H, Wang D, Pandey A, Cottee RJ, Boeke JD. Insights into the role of histone H3 and histone H4 core modifiable residues in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10060–10070. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.10060-10070.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa AS, Lenzmeier BA, Bessler JB, Goudsouzian LK, Schnakenberg SL, Zakian VA. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Moore DP, Blomberg MA, Braiterman LT, Voytas DF, Natsoulis G, Boeke JD. Hotspots for unselected Ty1 transposition events on yeast chromosome III are near tRNA genes and LTR sequences. Cell. 1993;73:1007–1018. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90278-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrova LY, et al. A reversible histone H3 acetylation cooperates with mismatch repair and replicative polymerases in maintaining genome stability. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan T, et al. Cell cycle- and chaperone-mediated regulation of H3K56ac incorporation in yeast. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib K, De Piccoli G. Surviving chromosome replication: the many roles of the S-phase checkpoint pathway. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:3554–3561. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengronne A, McIntyre G, Katou Y, Kanoh Y, Hopfner KP, Shirahige K, Uhlmann F. Establishment of sister chromatid cohesion at the S. cerevisiae replication fork. Mol Cell. 2006;23:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhou H, Wurtele H, Davies B, Horazdovsky B, Verreault A, Zhang Z. Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell. 2008;134:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas NL, Miller KM, DeFazio LG, Toczyski DP. Cell cycle and checkpoint regulation of histone H3 K56 acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4. Mol Cell. 2006;23:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto H, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Verreault A. A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response. Nature. 2005;436:294–298. doi: 10.1038/nature03714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megee PC, Morgan BA, Mittman BA, Smith MM. Genetic analysis of histone H4: essential role of lysines subject to reversible acetylation. Science. 1990;247:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.2106160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman TJ, Mamun MA, Nieduszynski CA, Blow JJ. Replisome stall events have shaped the distribution of replication origins in the genomes of yeasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:9705–9718. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir A, Spicuglia A, Lasonder E, Vermeulen M, Campsteijn C, Stunnenberg HG, Logie C. Characterization of lysine 56 of histone H3 as an acetylation site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25949–25952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Ye P, Yuan DS, Wang X, Bader JS, Boeke JD. A DNA integrity network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2006;124:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasero P, Bensimon A, Schwob E. Single-molecule analysis reveals clustering and epigenetic regulation of replication origins at the yeast rDNA locus. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2479–2484. doi: 10.1101/gad.232902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulovich AG, Hartwell LH. A checkpoint regulates the rate of progression through S phase in S. cerevisiae in response to DNA damage. Cell. 1995;82:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raths SK, Naider F, Becker JM. Peptide analogues compete with the binding of alpha-factor to its receptor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17333–17341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santocanale C, Sharma K, Diffley JF. Activation of dormant origins of DNA replication in budding yeast. Genes development. 1999;13:2360–2364. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian MD, Grunstein M. Functions of site-specific histone acetylation and deacetylation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:75–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.162114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoneau A, et al. Interplay between histone H3 lysine 56 deacetylation and chromatin modifiers in response to DNA damage. Genetics. 2015;200:185–205. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.175919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer F, Gerring SL, Connelly C, Hieter P. Mitotic chromosome transmission fidelity mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1990;124:237–249. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, et al. Ctf4 coordinates the progression of helicase and DNA polymerase alpha. Genes Cells. 2009;14:807–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaminy S, Newcomb B, Kim J, Gatbonton T, Foss E, Simon J, Bedalov A. Hst3 is regulated by Mec1-dependent proteolysis and controls the S phase checkpoint and sister chromatid cohesion by deacetylating histone H3 at lysine 56. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37805–37814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis JF, Newlon CS. Two compound replication origins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae contain redundant origin recognition complex binding sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2790–2801. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2790-2801.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis JF, et al. Identification of mutations that decrease the stability of a fragment of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome III lacking efficient replicators. Genetics. 2007;177:1445–1458. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.074690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis JF, et al. The DNA damage response pathway contributes to the stability of chromosome III derivatives lacking efficient replicators. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjeertes JV, Miller KM, Jackson SP. Screen for DNA-damage-responsive histone modifications identifies H3K9Ac and H3K56Ac in human cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:1878–1889. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubota JV, et al. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is catalyzed by histone chaperone-dependent complexes. Mol Cell. 2007;25:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuduri S, Tourriere H, Pasero P. Defining replication origin efficiency using DNA fiber assays. Chromosome Res. 2010;18:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s10577-009-9098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele H, et al. Histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation and the response to DNA replication fork damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:154–172. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05415-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, et al. Histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation is linked to the core transcriptional network in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell. 2009;33:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, et al. Histone H4 lysine 91 acetylation a core domain modification associated with chromatin assembly. Mol Cell. 2005;18:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Pu M, Zhang Z, Lou Z. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is important for genomic stability in mammals. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1747–1753. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi IW, et al. Rtt101 and Mms1 in budding yeast form a CUL4(DDB1)-like ubiquitin ligase that promotes replication through damaged DNA. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1034–1040. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Identification of a point mutation in HST3 using tiling microarray data and the SNPScanner algorithm. The likelihood that each nucleotide site is polymorphic, as compared with the S288c reference genome, was computed and compared for wildtype (green) and ofm6-1 mutant (yellow). A mutation was predicted at nucleotide 378,826 (yellow arrow) and confirmed by Sanger sequencing analysis (TIFF 1406 kb)

Figure S2 Unique mutations are not detected in the ofm6-1 mutant (yellow) in BUB3 or IRC12/YOR024W (TIFF 1717 kb)

Figure S3 Panel A Wild type (strain name), ofm6-1, hst3 and cdc15 were synchronized with alpha factor and release into nocodazole. Samples were collected at the alpha factor block (G1 cells), after 40 minutes after the block release (S phase cells) and at the nocodazole block (G2 cells). Cell cycle progression was monitored by FACS. Protein were extracted and run on an SDS-page gel, the blots were probed with both anti-H3 antibody and anti H3 K56 Ac. As expected in the wild type backgrond the H3 K56 acetyl signal is low, almost blank in G1 blocked cells, it gets incorporated during DNA synthesis and removed in G2. In the two hst3 isolates ofm6-1 and hst3Δ the H3K56 Ac signal remain strong in G2, suggesting that the acetyl group is not removed in the mutant. Panel B Wild type (strain name), rtt109Δ and ofm6-1 mutant were synchronized with alpha factor and release into nocodazole with and without nicodinammide. Samples were collected at the alpha factor block (alpha), after 40 minutes after the block release (40 minutes) and at the nocodazole block (100 minutes). Cell cycle progression was monitored by FACS. Treatment of the wild type with NAM causes accumulation of the h3 K56 acetylation in nocodazole blocked cells, suggesting it is recapitulating an hst3 phenotype (TIFF 7341 kb)