Abstract

Interleukin-33 (IL-33) is a cytokine that belongs to the interleukin-1 family and has been shown to be associated with mucosal inflammation. The aim of this study was to determine the serum level of IL-33 in children with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) and to correlate the level with the disease progression. In this cross sectional prospective study, we enrolled 50 children with IBD from KAUH, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia and 34 healthy control subjects between June 2012 and December 2012. Serum IL-33 was assessed by ELISA and CRP by immunonephelometric assay. Results from our study showed 32 CD and 18 UC patients included. The median age was 13.5 years for CD patients, 11.9 years for UC patients and 11.2 years for controls. Females constituted 53%, 66.7% and 59% of CD, UC and control subjects respectively. The median serum IL-33 in UC patients of 55.5 pg/mL was significantly higher than the median IL-33 level of 41 pg/mL in the healthy control (P=0.04) but no significant difference was found between the median IL-33 level in the sera of CD and the control group (P=0.7). A higher median IL-33 level was also found in active disease (P=0.03). In our cohort, the serum level of IL-33 was positively correlated with hs-CRP (r=0.48, P < 0.001). To conclude, our results support that serum IL-33 level is increased in children with UC as compared with control. Serum level is correlated with the disease activity; therefore it could be used as a potential biomarker for monitoring the severity of the disease in children with UC.

Keywords: IL-33, ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s disease (CD), children, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a group of chronic relapsing remitting inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. It comprises of ulcerative colitis (UC) that affect solely the mucosa of the colon and rectum and Crohn’s disease (CD) that may involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract, and is associated with discontinuous transmural lesions of the gut wall. Both are characterized by overall epithelial barrier dysfunction and unrelenting leakiness consequential from dysregulated immune responses. Several recent studies have predicted significant increase in IL-33 expression in the inflamed mucosa of 1BD patients in comparison to healthy controls, more predominantly in UC.

The pathogenesis of 1BD was open after the discovery of Interleukin-33 (IL-33) in 2005, recognized with abundant and pragmatic immunomodulating effect of this cytokine in diversity of cells. In the current era, Interleukin-33 (IL-33) is an illustrated member of the IL-1-family of cytokines, and it is a ligand of the ST2 receptor. Schmitz et al. established that NF-HEV is a member of the IL-1 cytokine superfamily and shared several molecular properties with IL-1a⁄b (IL-1F1/IL-1F2), IL-1Ra (IL-1F3), and IL-18 (IL-1F4). At this time, we have little comprehension about its authentic role except that it may perhaps help in controlling the specialized phenotype of HEV. However, its presence is also established in antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. Moreover, IL-33 mRNA expression levels have been shown in different tissue and organs including spleens and the central nervous system. It has been suggested that IL-33 is released through cell necrosis; it is bioactive and triggers inflammation in an autocrine or paracrine manner. It could be a novel target for the treatment of a variety of diseases; many earlier studies have demonstrated that IL-33 perhaps encompasses a pleiotropic role in diverse diseases. Recent works have demonstrated the role of IL-33 in chronic autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases.

Consequently, the effects of IL-33 could be either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory depending on the severity and condition of disease. The present studies are suggestive of IL-33 as distinctively unrestrained during cellular death due to necrosis and considered to be coupled with tissue damage during infection or trauma. Considering these properties, IL-33 has been predicted to alert the immune system of any endogenous danger after infection or trauma or in intracrine way it acts as a negative regulator of NFκB gene transcription. This led to numerous studies exploring its immunomodulatory function. In addition to this, involvement of IL-33 was shown in the modulation of inflammation, since it can prop up inflammatory and fibrotic disorders of gastrointestinal tract, rheumatic and airway inflammatory diseases and anaphylactic shock. Signaling in the course of ST2 emerge to be triggered through the cytoplasmic Toll-interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain of IL-1 accessory protein (IL-1 RAcP). This eventually leads to recruitment of the adaptor protein MyD88 and activation of NF-kB through TRAF6, IRAK1/4 and MAP kinases. Therefore, IL-33 appears to be a cytokine with dual role, through activation of the ST2L receptor complex as well as an intracellular nuclear factor with transcriptional regulatory properties.

Hence, the aim of this study was to assess the expression of serum IL-33 in children with UC and CD and to correlate the serum level with the disease activity.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

In this cross sectional prospective study, we enrolled 50 children and adolescents with clinical diagnosis of IBD seen at the Paediatric Gastroenterology Clinic at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, and 34 healthy control subjects during the period from June 2012 through December 2012. A written informed consent was obtained from the children’s parents or guardians before enrollment. The diagnosis of UC and CD was based on the international criteria established by the working groups of the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) depending on a combination of clinical, laboratory, imaging, endoscopic, and histopathology features. The extent of the disease in UC patients was classified based on Montreal classification into distal colitis (mucosal changes limited to the rectum and sigmoid), left sided colitis (mucosal changes up to the splenic flexure), or extensive colitis (mucosal changes beyond the splenic flexure). The disease phenotype in CD was classified according to Vienna classification into small bowel disease (L1), isolated colonic disease (L2) and ileocolonic disease (L3). For UC patients Mayo UC endoscopic score was used for assessment of mucosal inflammation.

Clinical disease activity was assessed using the abbreviated Pediatric Crohn’s Activity Index (abbrPCDAI) for patients with CD. A cut-off score of < 10 in the abbrPCDAI define remission. For patients with UC, Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) was used to assess the disease activity. A score of < 10 denotes disease remission.

Clinical data for IBD patients were obtained retrospectively from their medical records. The control group comprised of healthy children and adolescents who had no history of chronic illness including immune mediated disorders. The study was approved by the Bioethical and Research Committee at Faculty of Medicine at King Abdulaziz University, and the study was conducted according to the principles of Helsinki Declaration.

Preparation of patient’s samples

Blood samples were collected from patients and controls in EDTA tube that was stored in -80 until processed. Sera were separated by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes.

Measurement of IL-33 by ELISA

Serum samples were assessed by ELISA. The ELISA method was established according to the commercial kit protocol (DuoSet ELISA development system; R&D; USA). ELISA plate was coated with 100 µl of diluted capture antibody and was sealed and incubated overnight at room temperature. Then the antibody was removed and the plate was washed with washing buffer and then 300 µl of the reagent diluents was added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Then 100 µl of serum samples and standard were added and the plate was covered with adhesive strip and incubated for 2 hours. The plate was washed many times and this was followed by addition of 100 µl of detection antibody to each well and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After incubation 100 µl of working dilution conjugate (streptavidin-HRP) was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours. Substrate was added for color development. Finally, stop solution was added for blocking the development of color and the plate was analyzed using the ELISA reader. Calculation of results was done using standard curve which was plotted to determine the regression analysis.

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) method

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was measured by an immunonephelometric assay on a BN II analyzer (SIEMENS, Marburg, Germany) using SIEMENS kit for hs CRP assay. This assay is based on particle-enhanced immunonephelometry and it enables the measurement of CRP concentrations as low as 0.175 mg/l. The assay was based on the measurement of polystyrene particles coated with monoclonal antibodies specific to human CRP that aggregate when mixed with samples containing human CRP. The intensity of the scattered light is proportional to the concentration of the relevant protein in the sample. However, a blood sample was collected and serum was separated and diluted at 1:20 by N diluents’. Siemens control sera was used as recommended by the manufacturer. Results were calculated using the standard curve that is automatically plotted using a standard sample obtained from the manufacturer, as described in the manufacturer insert.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19 software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, III). Data were expressed as the percentage of the total for categorical variables, as the mean with standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed continuous variables. Data with parametric distribution were analyzed by Student’s t test or the Mann-Whitney U test with non parametric distribution. Correlations between each variable were evaluated using Spearman rank-order correlation test. All statistical analyses utilized a 0.05 level of significance.

Results

This study includes 50 patients with IBD (32 CD and 18 UC) and 34 control subjects. The median age was 13.5 years (range 1.3-16.4 years) for CD patients, 11.9 years (range, 5-18.3 years) for UC patients and 11.2 years (2.8-17.1 years) for controls. Females constituted 53%, 66.7% and 59% of CD patients, UC patients and controls respectively. Clinical and demographic characteristics for both CD and UC patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with Crohn’s disease (n=32)

| Patient’s parameters | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 11.57±3.96 |

| Male: Female ratio | 1:1.13 |

| Disease localization (CD), n (%) | |

| Ileal | 7 (21.9) |

| Colonic | 9 (28.1) |

| Ileocolonic | 16 (50) |

| Disease behavior, n (%) | |

| Inflammatory | 26 (81.3) |

| Stricturing | 4 (12.5) |

| Penetrating | 2 (6.3) |

| Perianal disease modifier | 8 (25) |

| Biological treatment, n (%) | 12 (37.5) |

Table 2.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with ulcerative colitis (n=18)

| Patient’s parameters | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 11.09±3.9 |

| Male: Female ratio | 1:2 |

| Disease localization, n (%) | |

| Proctitis | 2 (11.1) |

| Left sided colitis | 3 (16.7) |

| Extended colitis | 12 (66.7) |

| Pancolitis | 1 (5.6) |

| Mayo score, n (%) | |

| Score 2 | 6 (33.3) |

| Score 3 | 12 (66.7) |

| Biological treatment, n (%) | 5 (27.8) |

IL-33 levels in sera of IBD patients and controls

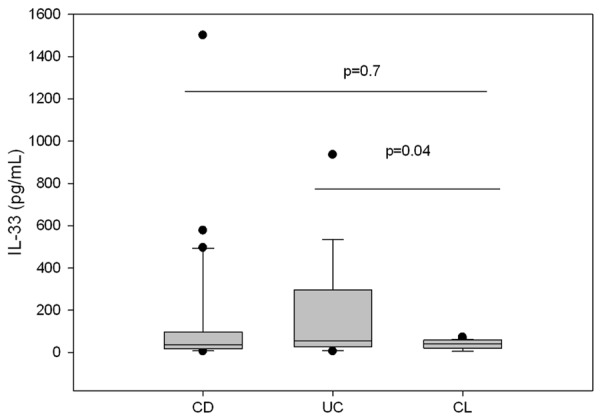

The median serum IL-33 in UC patients of 55.5 pg/mL (range, 5.5-935 pg/mL) was significantly higher than the median IL-33 level of 41 pg/mL (range, 5.5-72 pg/mL) in the healthy control (U=200.5, P=0.04) using Mann-Whitney test but no significant difference was found between the median IL-33 level in the sera of CD of 37.9 pg/mL (range, 5.5-1500 pg/mL) as compared to the median IL-33 of 41 pg/mL (range, 5.5-72 pg/mL) in the control group (U=514.5, P=0.7) Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Median values of serum IL-33 in pediatric patients with CD, UC and controls.

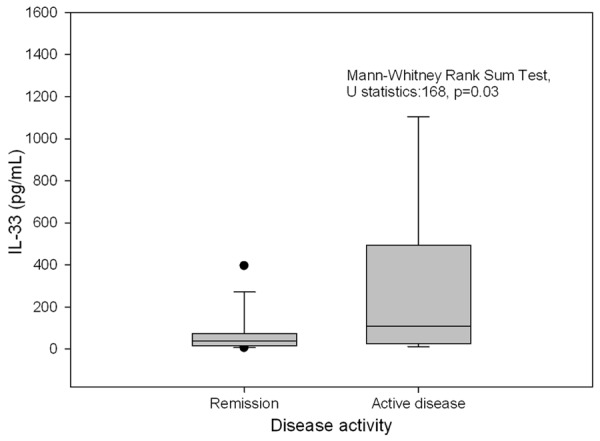

IL-33 levels in relation to clinical disease activity

The median IL-33 levels were compared between IBD group with activity indices less than 10 for either abbrPCDAI or PUCAI and groups with higher activity indices indicating clinically active disease. The median IL-33 level in sera of patients with flare up (n=16) of 110 pg/mL (range, 27.5-493.8 pg/mL) was significantly higher than the median IL-33 level of 39 pg/mL (range, 17.2-73.2 pg/mL) in patients in remission (n=34), U=168, P=0.03 Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Median IL-33 levels in pediatric IBD patients in relation to disease activity.

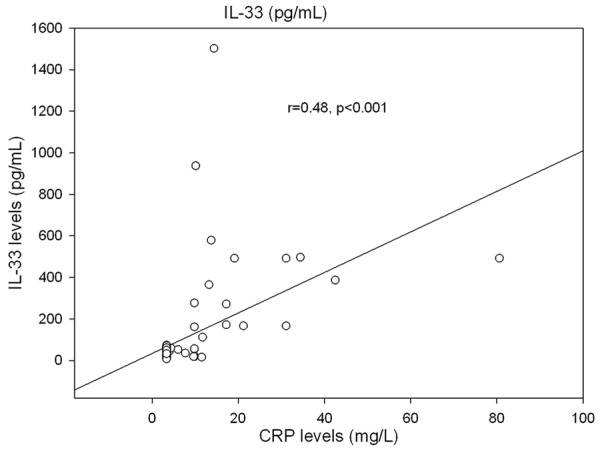

Correlation of the IL-33 level with CRP

The correlation of the serum level of IL-33 was also tested against CRP that was considered a marker of monitoring the disease activity in IBD patients. The serum level of IL-33 was positively correlated with the CRP level (r=0.48, P < 0.001) Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The correlation between IL-33 level and CRP in pediatric patients with IBD.

Effect of treatment with anti-TNF-alpha medications on the serum level of IL-33

On further examination of the effect of biological therapy with anti-TNF-alpha medications on serum IL-33 levels, we compare the IL-33 levels between two groups (a group who was treated with anti-TNF-alpha (n=17) and a group who did not receive treatment with anti-TNF-alpha medications (n=33). We did not find statistically significant difference between the two groups (median IL-33 level of 45 pg/mL vs. median IL-33 level of 51 pg/mL, U=261.5, P=0.69).

Discussion

In this prospective study of IBD with striking representation of patients of both CD and UC with distinct disease localization and varied disease behavior, suitably judged against healthy controls, we observed significant increase in serum IL-33 in patients of IBD in comparison with control group, nevertheless, this finding was highly pronounced more in favor of UC rather than CD. Recent reports indicates that throughout active UC, distinctive escalation of IL-33 was observed in intestinal epithelial cells as well as in infiltrating lamina propria mononuclear cells, which belongs to the monocyte/and B-cell families. Consistently, amplification of IL-33 serum concentrations were also observed in IBD patients compared to healthy controls of same age cohorts.

Our findings are supported by several studies reminiscent of up regulation of IL-33 mRNA expression in human biopsy specimens from untreated or active UC patients compared with healthy controls have been testified by several studies. Furthermore, it was reported that, in UC the major location for IL-33 expression was found in sub epithelial myofibroblasts (SEMFs) below the ulcerative lesion, but not observed in CD patients, indicative of the potential role for IL-33 in wound/ulcer healing, which may be different in UC compared with CD. Similarly, ST2 transcripts have been reported in mucosa samples from patients with active UC. The intestinal tissue expression of ST2 was significantly different in healthy mucosa compared with chronically inflamed IBD patients, in which ST2 was abundantly expressed in non-inflamed colon epithelium, while during chronic inflammation its expression was lost, reduced or redistributed.

Another key finding in our study was a link between the progression of the disease activity in both UC and CD with the serum levels of IL-33 on the basis of its analysis by the hs-CRP levels. This observation of serum levels of IL-33 in IBD patients has been supported by the results of recent studies which revealed in SAMP1/YitFc (SAMP) mice, an experimental model of DC ileitis , illustrated by an early Th1 immune response and Th2 cytokines dominated late and chronic phase of disease process. It is quite relevant that escalated serum levels of IL-33 in IBD patients replicate an active inflammatory condition and symbolize a prospective biomarker for the disease activity. In addition, we also observed that irrespective of biological therapy, there was no divergence in the serum levels of IL-33 among the IBD group throughout the phase of the assessment. A limitation of our study is that the numbers of patients and controls available for study were relatively small which could decrease the statistically significant relationship from the data.

In conclusion, serum IL-33 expression was increased in children with UC as compared with control. Therefore increased serum IL-33 level could be used for differentiating CD from UC in patients with indeterminate colitis. Serum level was positively correlated with the disease activity; therefore, it could be used as a potential biomarker for monitoring disease progression in children with UC.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Deanship for Scientific research at King Abdulaziz University for supporting the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Group for this work.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Söderholm JD, Olaison G, Peterson KH, Franzén LE, Lindmark T, Wirén M, Tagesson C, Sjödahl R. Augmented increase in tight junction permeability by luminal stimuli in the non-inflamed ileum of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2002;50:307–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gitter AH, Wullstein F, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Epithelial barrier defects in ulcerative colitis: characterization and quantification by electrophysiological imaging. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1320–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.29694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beltrán CJ, Núñez LE, Díaz-Jiménez D, Farfan N, Candia E, Heine C, López F, González MJ, Quera R, Hermoso MA. Characterization of the novel ST2/IL-33 system in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1097–107. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobori A, Yagi Y, Imaeda H, Ban H, Bamba S, Tsujikawa T, Saito Y, Fujiyama Y, Andoh A. Interleukin-33 expression is specifically enhanced in inflamed mucosa of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:999–1007. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastorelli L, Garg RR, Hoang SB, Spina L, Mattioli B, Scarpa M, Fiocchi C, Vecchi M, Pizarro TT. Epithelial-derived IL-33 and its receptor ST2 are dysregulated in ulcerative colitis and in experimental Th1/Th2 driven enteritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912678107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seidelin JB, Bjerrum JT, Coskun M, Widjaya B, Vainer B, Nielsen OH. IL-33 is upregulated in colonocytes of ulcerative colitis. Immunol Lett. 2010;128:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu J, Carver W. Effects of interleukin-33 on cardiac fibroblast gene expression and activity. Cytokine. 2012;58:368–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willems S, Hoefer I, Pasterkamp G. The role of the interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 (ST2) and Interleukin-33 pathway in cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk assessment. Minerva Med. 2012;103:513–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S, Ding L, Liu SS, Wang C, Leng RX, Chen GM, Fan YG, Pan HF, Ye DQ. IL-33: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Autoimmune Diseases. J Investig Med. 2012;60:1151–6. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31826d8fcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liew FY. IL-33: a Janus cytokine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(Suppl 2):i101–4. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu D, Jiang HR, Li Y, Pushparaj PN, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Leung BP, Mu R, Tay HK, McKenzie AN, McInnes IB, Melendez AJ, Liew FY. IL-33 exacerbates autoantibody-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2010;184:2620–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komai-Koma M, Gilchrist DS, McKenzie AN, Goodyear CS, Xu D, Liew FY. IL-33 activates B1 cells and exacerbates contact sensitivity. J Immunol. 2011;186:2584–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DE. The biological paths of IL-1 family members IL-18 and IL-33. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:383–92. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0810470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haraldsen G, Balogh J, Pollheimer J, Sponheim J, Küchler AM. Interleukin-33-cytokine of dual function or novel alarmin? Trends Immunol. 2009;30:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stolarski B, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Kewin P, Xu D, Liew FY. IL-33 exacerbates eosinophil-mediated airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;185:3472–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattler S, Smits HH, Xu D, Huang FP. The Evolutionary Role of the IL-33/ST2 System in Host Immune Defense. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2013;61:107–17. doi: 10.1007/s00005-012-0208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie Q, Wang SC, Zhong J, Li J. Therapeutic potential of IL-33 in rheumatoid arthritis: A comment about the article by Talabot-Ayer D, et al,“Distinct serum and synovial fluid interleukin (IL)-33 levels in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis”, Joint Bone Spine 2012;79:32-7. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;80:116–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin H, Li XY, Liu T, Yuan BH, Zhang BB, Hu SL, Gu HB, Jin XB, Zhu JY. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of soluble ST2 attenuates ovalbumininduced allergic asthma in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;170:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YH, Park CS, Lim DH, Ahn SH, Son BK, Kim JH, Jang TY. Beneficial effect of anti-interleukin-33 on the murine model of allergic inflammation of the lower airway. J Asthma. 2012;49:738–43. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.702841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komai-Koma M, Brombacher F, Pushparaj PN, Arendse B, McSharry C, Alexander J, Chaudhuri R, Thomson NC, McKenzie AN, McInnes I, Liew FY, Xu D. Interleukin-33 amplifies IgE synthesis and triggers mast cell degranulation via interleukin-4 in naive mice. Allergy. 2012;67:1118–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oboki K, Ohno T, Kajiwara N, Arae K, Morita H, Ishii A, Nambu A, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Matsumoto K, Sudo K, Okumura K, Saito H, Nakae S. IL-33 is a crucial amplifier of innate rather than acquired immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18581–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groβ P, Doser K, Falk W, Obermeier F, Hofmann C. IL-33 attenuates development and perpetuation of chronic intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1900–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IBD Working Group of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis--the Porto criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000163736.30261.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; Colitis Foundation of America. Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, Dubinsky MC, Glickman JN, Gold BD, Griffiths AM, Jevon GP, Higuchi LM, Hyams JS, Kirschner BS, Kugathasan S, Baldassano RN, Russo PA. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:653–74. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805563f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D’Haens G, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Jewell DP, Rachmilewitz D, Sachar DB, Sandborn WJ, Sutherland LR. A simple classification of Crohn’s disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8–15. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Present D, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shepanski MA, Markowitz JE, Mamula P, Hurd LB, Baldassano RN. Is an abbreviated Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index better than the original? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:68–72. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, Hyams J, de Bruijne J, Uusoue K, Walters TD, Zachos M, Mamula P, Beaton DE, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:423–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ledue TB, Weiner DL, Sipe JD, Poulin SE, Collins MF, Rifai N. Analytical evaluation of particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assays for C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A and mannose-binding protein in human serum. Ann Clin Biochem. 1998;35:745–53. doi: 10.1177/000456329803500607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastorelli L, De Salvo C, Cominelli MA, Vecchi M, Pizarro TT. Novel cytokine signaling pathways in inflammatory bowel disease: insight into the dichotomous functions of IL-33 during chronic intestinal inflammation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4:311–23. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11410770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sponheim J, Pollheimer J, Olsen T, Balogh J, Hammarström C, Loos T, Kasprzycka M, Sørensen DR, Nilsen HR, Küchler AM, Vatn MH, Haraldsen G. Inflammatory bowel disease-associated interleukin-33 is preferentially expressed in ulceration-associated myofibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2804–15. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunawardena CK, Zijlstra RT, Beltranena E. Characterization of the nutritional value of airclassified protein and starch fractions of field pea and zero-tannin faba bean in grower pigs. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:660–70. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bamias G, Martin C, Mishina M, Ross WG, Rivera-Nieves J, Marini M, Cominelli F. Proinflammatory effects of TH2 cytokines in a murine model of chronic small intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:654–66. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rivera-Nieves J, Bamias G, Vidrich A, Marini M, Pizarro TT, McDuffie MJ, Moskaluk CA, Cohn SM, Cominelli F. Emergence of perianal fistulizing disease in the SAMP1/YitFc mouse, a spontaneous model of chronic ileitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:972–82. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]