Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the expression status of Dual-Specificity Phosphatase 5 Pseudogene 1 (DUSP5P1) and its clinical relevance in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) was performed to detect the status of DUSP5P1 expression in 89 patients with de novo AML and 24 normal controls. The level of DUSP5P1 expression was significantly up-regulated in AML compared to controls (P=0.031). The patients with high expression of DUSP5P1 had higher percentage of blasts in bone marrow (BM) than those without high expression (P=0.027). The occurrence rate of DUSP5P1 high expression was significantly higher in M1 (2/8, 25%) and M2 subtypes (9/33, 27%) than in M3 subtype (0/17, 0%) (P=0.034). At the same time, the frequency of DUSP5P1 high expression in patients with intermediate (13/53, 24%) and poor karyotypes (5/11, 45%) was significantly higher than that in patients with favorable karyotype (0/21, 0%) (P=0.003). Meanwhile, DUSP5P1 high-expressed patients had significantly shorter overall survival (OS) than those with low expression (median 4.5 vs. 10.5 months, respectively, P=0.038). Our findings indicated that high expression of DUSP5P1 may identify high-risk AML patients and is associated with poor prognosis in AML.

Keywords: Pseudogene, DUSP5P1, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), prognostic

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the most common acute leukemia in adults, is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of undifferentiated blast cells in the peripheral blood and bone marrow [1,2]. Cytogenetic abnormalities have general been considered to be the most crucial independent prognostic parameter in AML, besides, gene mutations also constitute the key events in AML pathogenesis [3,4]. Further research into the role of the underlying genetic and epigenetic description of the malignant cells may provide us more possiblility to deeply understand the mechanism of leukemogenesis in AML, as well as offering important prognostic information and highlighting potential therapeutic targets [5].

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways constitute a evolutionarily conserved family of signaling modules by cells which transduce extracellular signals into intracellular responses that control multiple cellular processes [6,7]. Three main MAPK signaling cascades have been characterized in mammals, including ERKs, JNKs, and p38MAPKs [8]. The extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) pathway, one of the most studied MAPK pathways, lies downstream of the cellular protooncogene Ras and has been implicated in numerous cellular activities including cell proliferation, differentiation and survival [9,10]. Meanwhile, abnormalities in the regulation of this pathway can result in uncontrolled proliferation and initiation of cancer [11,12]. Furthermore, the MAPK/ERK pathway also plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of various hematological malignancies [13,14].

DUSPs, also known as MAPK phosphatases (MKPs), constitute a distinct family of proteins that mediate spatiotemporal aspects of MAPK pathways [15,16], which have been shown to play an important role in sustaining proliferation in a large percentage of myeloid leukemias [8,17]. DUSP5, belongs to the DUSPs family, is a nuclear phosphatase that targets and anchors MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase) 1/2, but not other MAPK kinases [18], and acts as a negative feedback regulator of the MAPK pathway which might led to signals promoting or inhibiting cell growth and survival [19]. Recently, it also has been proposed to be a tumor suppressor in several cancers including hematopoietic malignancies [20,21].

Pseudogenes are sequences typically characterized by close similarities to one or more paralogous genes, yet lost the ability to produce functional protein mostly due to mutation or aberrant duplication [22,23]. However, recent evidences support that they can serve as the raw and processed materials for the exaptation of novel functions, particularly in relation to the regulation of parental gene expression [24]. To date, there are four DUSP5-related pseudogenes have been identified in the human genome including DUSP5P1, DUSP5P2, DSUP5Psi3 and DSUP5Psi4 [21]. DUSP5P1 is located on human chromosomal band 1q42, with high homology to DUSP5 [21]. Although DUSP5P1 over-expression has been observed in some cancer cell lines including Hodgkin’s lymphoma cell lines, hematopoietic tumor cell lines, neuroblastoma cell lines and Ewing sarcoma cell lines [21], its expression status and biological function have remained largely uncharacterized in AML. In our study, real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) was used to measure the DUSP5P1 expression in AML patients and normal controls. We investigated the expression status of DUSP5P1 and the clinical relevance in AML patients.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated People’s Hospital of Jiangsu University. The bone marrows derived from 113 samples, including 89 de novo AML diagnosed at the Affiliated People’ Hospital of Jiangsu University and 24 normal controls, were obtained after written informed consent. French-America-British (FAB) and World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (blast ≥20%) were used to approach the diagnosis and classification of AML patients [25,26]. Karyotypes were analyzed by traditional R-banding method. Karyotype risk in AML was classified according to the reported study [27]. The main clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patient cohort were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation between DUSP5P1 expression and patients parameters

| Patient’s parameters | Status of DUSP5P1 expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Low (n=70) | High (n=19) | P | |

| Sex, male/female | 39/31 | 11/8 | 1.000 |

| Median age, years (range) | 55 (10-87) | 62 (29-85) | 0.226 |

| Median hemoglobin, g/L (range) | 78 (34-138) | 71 (32-100) | 0.262 |

| Median WBC, ×109/L (range) | 10.3 (0.3-528.0) | 25.9 (1.5-92.8) | 0.224 |

| Median platelets, ×109/L (range) | 32.5 (3-264) | 42 (7-110) | 0.467 |

| BM blasts, % (range) | 42.5 (1.0-97.5) | 69.5 (1.0-109) | 0.027 |

| FAB | 0.099 | ||

| M1 | 6 | 2 | |

| M2 | 24 | 9 | |

| M3 | 17 | 0 | |

| M4 | 15 | 7 | |

| M5 | 7 | 1 | |

| M6 | 1 | 0 | |

| WHO | 0.092 | ||

| AML with t(8;21) | 4 | 0 | |

| APL with t(15;17) | 17 | 0 | |

| AML without maturation | 6 | 2 | |

| AML with maturation | 20 | 9 | |

| Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | 15 | 7 | |

| Acute monoblastic and monocytic leukemia | 6 | 1 | |

| Acute erythroid leukemia | 1 | 0 | |

| No data | 1 | 0 | |

| Karyotype classification | 0.003 | ||

| Favorable | 21 | 0 | |

| Intermediate | 40 | 13 | |

| Poor | 6 | 5 | |

| No data | 3 | 1 | |

| Karyotype | 0.011 | ||

| Normal | 34 | 11 | |

| t(8;21) | 4 | 0 | |

| t(15;17) | 17 | 0 | |

| Complex | 4 | 5 | |

| Others | 8 | 2 | |

| No data | 3 | 1 | |

| Gene Mutation* | |||

| C/EBPA (+/-) | 7/59 | 3/14 | 0.420 |

| NPM1 (+/-) | 8/56 | 0/15 | 0.341 |

| FLT3 ITD (+/-) | 10/54 | 1/14 | 0.680 |

| C-KIT (+/-) | 0/64 | 1/14 | 0.190 |

| CR (+/-) | 39/29 | 9/10 | 0.449 |

WBC, white blood cells; FAB, French-American-British classification; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; CR, complete remission;

percentage was equal to the number of mutated patients divided by total cases in each group.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and real-time quantitative PCR

The bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMNCs) were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. Total RNA was isolated by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

cDNA was generated by using 2 μg of total RNA in a total volume of 40 μL including random hexamers 10 μM, dNTPs 10 mM each, RNase inhibitor (RNAsin) 80 units, and MMLV reverse transcriptase (MBI Fermentas, Hanover, USA) 200 units. The reverse transcription system was incubated for 10 min at 25°C, 60 min at 42°C, and then stored at -20°C.

DUSP5P1 was amplified using the primers 5’-GTGCTGAACTAGGGGAGCTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-AGATGGTGGGTGAACAGGAG-3’ (reverse) with expected products of 548 bp. Real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) was carried out for all sample in a final reaction volume of 20 μL, consisting of 0.25 μM of primers, 10 μL SYBR Premix Ex Taq II, 0.4 μL 50×ROX (TaKaRa, Japan) and 50 ng of cDNA. RQ-PCR was performed on Step One Plus (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Amplification was carried out at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 5 s, 62°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, and an fluorescence collection step at 81°C for 30 s, then followed by a melting program at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 60 s, 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 15 s. Negative and positive controls were involved in all assays. The specificity of RQ-PCR products was certified by melting curves and DNA sequencing. The housekeeping gene (ABL) was used to calculate the abundance of DUSP5P1 mRNA. Relative DUSP5P1 expression values were achieved according to the following equation: NDUSP5P1=(EDUSP5P1)ΔCT (DUSP5P1control-sample)÷(EABL)ΔCT ABL (control-sample)×1000‰. The parameter efficiency (E) derived from the formula E=10(-1/slope) (the slope referred to CT versus cDNA concentration plot).

Gene mutation detection

NPM1 and C-KIT mutations were detected by high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA) as reported previously [28]. Briefly, genomic DNA samples were amplified using gene-specific primers. Then, mutation scanning was conducted for PCR products using HRMA with the LightScannerTM platform (Idaho Technology Inc, Salt Lake City, Utah). To confirm the results of HRMA, all positive samples were detected using direct DNA sequencing. C/EBPA mutations and FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) were directly DNA sequenced [29,30].

Statistical analysis

All statistics were analyzed with the SPSS 18.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Pearson Chi-square analysis or Fisher exact test was employed to compare the difference of categorical variables between patients groups. At the same time, Kruskal-Wallis test (multiple groups) and Mann-Whitney U-test (two groups) were executed to compare the distinction of continuous variables between patients groups and controls. The correlation between DUSP5P1 expression and the clinical hematologic parameters was analyzed with Spearman’s rank correlation. Overall survival (OS) was estimated following the Kaplan-Meier method. For all analyses, a two-tailed P value of 0.05 or less was considered as statistically significant.

Results

DUSP5P1 expression in AML

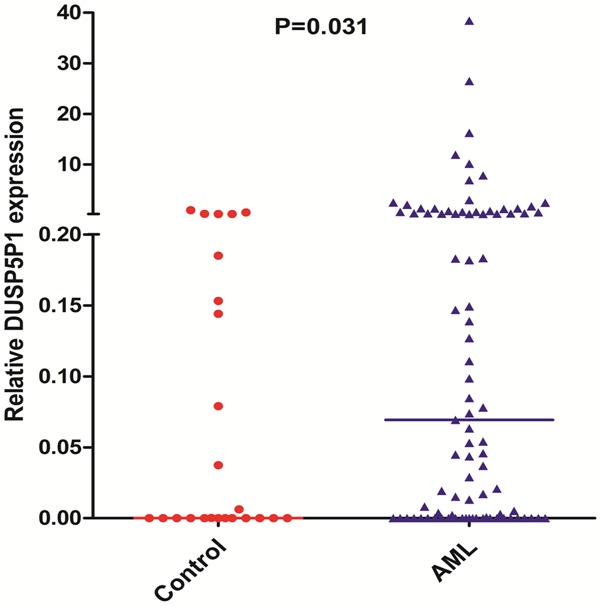

We evaluated the level of DUSP5P1 expression in AML patients and normal controls. DUSP5P1 expression in AML (0-809.80, median 0.6930) increased significantly compared to controls (0-1.00, median 0.0013) (P=0.031, Figure 1). A NDUSP5P1 ratio equal to or above 0.798 (determined as the mean plus 3 SD) was selected to distinguish DUSP5P1 expression in AML according to NDUSP5P1 ratio of all controls. Then this cohort of 89 AML patients was divided into two groups: low DUSP5P1 expression (<0.798) and high DUSP5P1 expression (≥0.798).

Figure 1.

Relative expression levels of DUSP5P1 in AML and controls.

Association of DUSP5P1 expression with clinical and laboratory characteristics in AML

There was no significant difference in sex, age, hemoglobin, white blood cells, platelet count and gene mutations between these two groups (Table 1). However, DUSP5P1 high-expressed patients had significantly higher percentage of blasts in bone marrow (BM) than low-expressed patients (P=0.027) (Table 1). Moreover, among AML subtypes of M1/M2/M3, the occurrence rate of DUSP5P1 high expression was significant higher in M1 (2/8, 25%) and M2 subtypes (9/33, 27%) than in M3 subtype (0/17, 0%) (P=0.034). According to karyotype classification, the patients with intermediate (13/53, 24%) and poor karyotypes (5/11, 45%) had significant higher frequency of DUSP5P1 high expression than patients with favorable karyotype (0/21, 0%) (P=0.003).

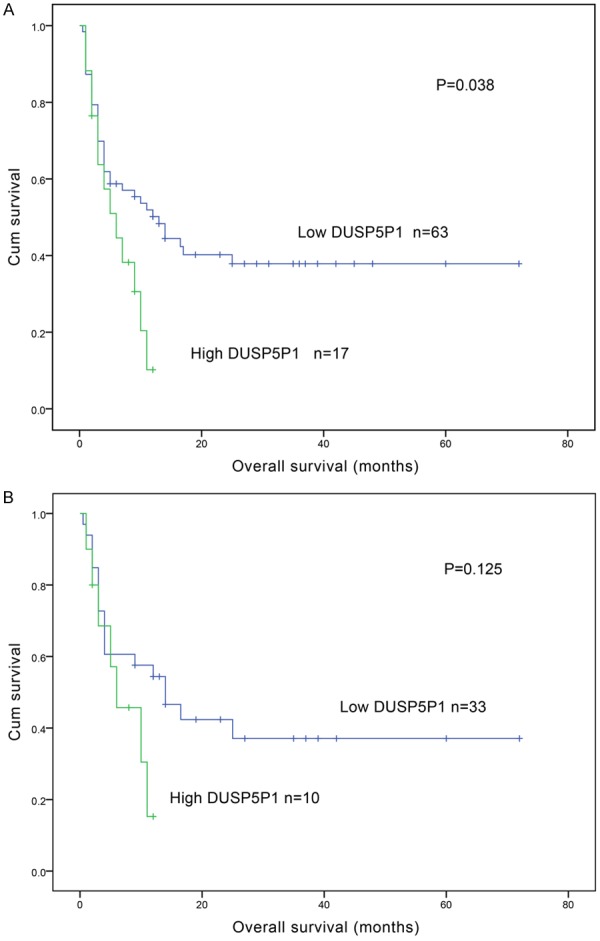

Impact of DUAP5P1 expression on outcome of AML patients

There was no significant difference between DUSP5P1 high-expressed patients and DUSP5P1 low-expressed patients in the rates of complete remission (CR) after induction therapy (P=0.449) (Table 1). However, DUSP5P1 high-expressed patients had significant shorter overall survival (OS) than those with low expression (median 4.5 versus 10.5 months, respectively, P=0.038) (Figure 2A). While, among cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML) patients, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no significant difference between cases with and without high DUSP5P1 expression (median 5.5 versus 12 months, respectively, P=0.125) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

A. Survival analysis of DUSP5P1 expression levels with overall survival of AML patients; B. Overall survival of cytogenetically normal patients.

Discussion

Traditionally, pseudogenes, regarded as ‘junk DNA’, are sequence either not transcribed or not translated into functional proteins [22,31]. However, in recent studies it is indicated that many pseudogenes are transcribed and have lots of effects on DNA, RNA and protein in both health and disease, especially in cancer [31]. In various studies, some pseudogenes expression can influence its parental genes’ expression, including downregulation and upregulation [21,32]. Meanwhile, pseudogene also has been studied to present differential expression in cancer tissues, suggesting that it may act as a biomarker for specific cancers [33]. DUSP5P1 is one pseudogene of DUSP5 in the human genome. Staege Martin S et al. have observed that DUSP5P1 is high-expressed while DUSP5 is low-expressed in HL cell lines, which implies that DUSP5P1 may down-regulate its parental gene (DUSP5) expression [21]. The pattern of DUSP5P1 expression in AML and its clinical significance, however, still remains unknown.

In the present study, we show for the first time that DUSP5P1 expression in AML increased significantly compared to controls. This result was consistent with the observations in HL cell lines [21]. At same time, no significant association is observed between DUSP5P1 high expressions with clinical parameters except for percentage of BM blasts. DUSP5, as the real gene of DUSP5P1, can negative feedback regulate MAPK/ERK pathway. Moreover, down-regulated MAPK/ERK activation can suppress proliferation and induces the apoptosis of AML blasts [34]. Inhibition of DUSP5 (probably due to DUSP5P1 expression) might result in enhanced activation of the ERK pathway and subsequent increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of AML blasts. Interestingly, downregulation of DUSP5 expression also be found in gastric cancer by promoter CpG island hypermethylation and its methylation may act as a valuable epigenetic biomarker to predict the clinical outcome for GC patients [20]. To the best of our knowledge, an corroborate relationship between promoter hypermethylation and its pseudogene (DUSP5P1) expression for DUSP5 in AML has not been documented in the any literature. Whether hypermethylation of the DUSP5 promoter is correlated with DUSP5P1 expression and affects the clinical outcome for AML should be further investigated. In the future, more cases should be investigated to further determine its clinical significance in AML.

The difference in the rates of complete remission (CR) between patients with and without high expression of DUSP5P1 was not found due to the small size of samples. An interesting finding in this study was that high expression of DUSP5P1 was significantly associated with unfavorable overall survival in AML patients, indicating that upregulated DUSP5P1 expression might be an adverse prognostic factor in AML. Our study further demonstrated that high expression of DUSP5P1 occurred less frequently in patients of FAB-M3 subtype than in other subtype. At the same time, high expression of DUSP5P1 was more frequent in intermediate and poor karyotypes group. AML M3 in the FAB system (currently konwn as acute promyelocytic leukemia or PML-RARA in the WHO classification ) is characterized by the translocation t(15;17) and is regarded as a particular type of AML [35], both by the clinical characteristics and by the better survival rates than other subtypes [36,37]. In addition, cytogenetics provides a key point in the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of AML [27,38]. Risk stratification-into favorable, intermediate, or poor cytogenetic prognosis group-can then be allowed according to the cytogenetic profile of the patient [27]. Complex karyotypes (two or more unrelated abnormalities), monosomy of chromosome 5, monosomy of chromosome 7, translocations involving the 11q23 locus and all deletions were stratified into the poor cytogenetic prognosis. The intermediate prognosis group included normal karyotype and trisomies of chromosomes 4, 8 and 21. The translocations t(15;17), t(8;21) and inversion (16)/t(16;16) have the favorable impact on prognosis [27,39]. Moreover, the survival curves of patients with poor and intermediate prognosis cytogenetics were grouped together with the similar poor prognosis according to the reported study [39]. Taken together, we found downregulation expression of DUSP5P1 in patients of FAB-M3 subtype related to favorable prognosis and up-regulation expression of DUSP5P1 in patients both of poor and intermediate group related to poor prognosis in AML. Whether there is a functional connection between DUSP5P1 expression and outcome of AML patients or whether this is only a coincidence requires further investigations.

In summary, our study has shown that the increased DUSP5P1 expression is a common event in AML patients. Moreover, high DUSP5P1 expression may serve as a prognostic factor in AML patients. The detection of DUSP5P1 expression may be helpful to the diagnosis and prognostic stratification in AML.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science foundation of China (81172592, 81270630), Science and Technology Special Project in Clinical Medicine of Jiangsu Province (BL2012056), 333 Project of Jiangsu Province (BRA2011085).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Estey E, Dohner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:1894–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubnitz JE. Childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0059-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, Carroll AJ, Edwards CG, Arthur DC, Pettenati MJ, Patil SR, Rao KW, Watson MS, Koduru PR, Moore JO, Stone RM, Mayer RJ, Feldman EJ, Davey FR, Schiffer CA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renneville A, Roumier C, Biggio V, Nibourel O, Boissel N, Fenaux P, Preudhomme C. Cooperating gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: a review of the literature. Leukemia. 2008;22:915–931. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway O’Brien E, Prideaux S, Chevassut T. The epigenetic landscape of acute myeloid leukemia. Adv Hematol. 2014;2014:103175. doi: 10.1155/2014/103175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson MJ, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang SH, Sharrocks AD, Whitmarsh AJ. Transcriptional regulation by the MAP kinase signaling cascades. Gene. 2003;320:3–21. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00816-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geest CR, Coffer PJ. MAPK signaling pathways in the regulation of hematopoiesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:237–250. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb MH, Hepler JE, Cheng M, Robbins D. The mitogen-activated protein kinases, ERK1 and ERK2. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaul YD, Seger R. The MEK/ERK cascade: from signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawrence MC, Jivan A, Shao C, Duan L, Goad D, Zaganjor E, Osborne J, McGlynn K, Stippec S, Earnest S, Chen W, Cobb MH. The roles of MAPKs in disease. Cell Res. 2008;18:436–442. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Herrera R. Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to treat cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:937–947. doi: 10.1038/nrc1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platanias LC. Map kinase signaling pathways and hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2003;101:4667–4679. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson DE. Src family kinases and the MEK/ERK pathway in the regulation of myeloid differentiation and myeloid leukemogenesis. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2008;48:98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farooq A, Zhou MM. Structure and regulation of MAPK phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2004;16:769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson RJ, Keyse SM. Diverse physiological functions for dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4607–4615. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milella M, Kornblau SM, Estrov Z, Carter BZ, Lapillonne H, Harris D, Konopleva M, Zhao S, Estey E, Andreeff M. Therapeutic targeting of the MEK/MAPK signal transduction module in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:851–859. doi: 10.1172/JCI12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyse SM. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovanen PE, Rosenwald A, Fu J, Hurt EM, Lam LT, Giltnane JM, Wright G, Staudt LM, Leonard WJ. Analysis of gamma c-family cytokine target genes. Identification of dual-specificity phosphatase 5 (DUSP5) as a regulator of mitogen-activated protein kinase activity in interleukin-2 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5205–5213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin SH, Park SY, Kang GH. Downregulation of dual-specificity phosphatase 5 in gastric cancer by promoter CpG island hypermethylation and its potential role in carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staege MS, Muller K, Kewitz S, Volkmer I, Mauz-Korholz C, Bernig T, Korholz D. Expression of dual-specificity phosphatase 5 pseudogene 1 (DUSP5P1) in tumor cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pink RC, Wicks K, Caley DP, Punch EK, Jacobs L, Carter DR. Pseudogenes: pseudo-functional or key regulators in health and disease? RNA. 2011;17:792–798. doi: 10.1261/rna.2658311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mighell AJ, Smith NR, Robinson PA, Markham AF. Vertebrate pseudogenes. FEBS Lett. 2000;468:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts TC, Morris KV. Not so pseudo anymore: pseudogenes as therapeutic targets. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:2023–2034. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019–5032. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, Sultan C. Proposed revised criteria for the classification of acute myeloid leukemia. A report of the French-American-British Cooperative Group. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:620–625. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, Paietta E, Willman CL, Head DR, Rowe JM, Forman SJ, Appelbaum FR. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96:4075–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian J, Lin J, Qian W, Ma JC, Qian SX, Li Y, Yang J, Li JY, Wang CZ, Chai HY, Chen XX, Deng ZQ. Overexpression of miR-378 is frequent and may affect treatment outcomes in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2013;37:765–768. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, Harrison G, Langabeer SE, Belton AA, Walker H, Wheatley K, Bowen DT, Burnett AK, Goldstone AH, Linch DC. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2001;98:1752–1759. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin LI, Chen CY, Lin DT, Tsay W, Tang JL, Yeh YC, Shen HL, Su FH, Yao M, Huang SY, Tien HF. Characterization of CEBPA mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: most patients with CEBPA mutations have biallelic mutations and show a distinct immunophenotype of the leukemic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1372–1379. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao-Jie L, Ai-Mei G, Li-Juan J, Jiang X. Pseudogene in cancer: real functions and promising signature. J Med Genet. 2015;52:17–24. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiefari E, Iiritano S, Paonessa F, Le Pera I, Arcidiacono B, Filocamo M, Foti D, Liebhaber SA, Brunetti A. Pseudogene-mediated posttranscriptional silencing of HMGA1 can result in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Commun. 2010;1:40. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmena L. Pseudogene redux with new biological significance. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1167:3–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0835-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lunghi P, Tabilio A, Dall’Aglio PP, Ridolo E, Carlo-Stella C, Pelicci PG, Bonati A. Downmodulation of ERK activity inhibits the proliferation and induces the apoptosis of primary acute myelogenous leukemia blasts. Leukemia. 2003;17:1783–1793. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warrell RP Jr, de The H, Wang ZY, Degos L. Acute promyelocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:177–189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307153290307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asou N, Adachi K, Tamura J, Kanamaru A, Kageyama S, Hiraoka A, Omoto E, Akiyama H, Tsubaki K, Saito K, Kuriyama K, Oh H, Kitano K, Miyawaki S, Takeyama K, Yamada O, Nishikawa K, Takahashi M, Matsuda S, Ohtake S, Suzushima H, Emi N, Ohno R. Analysis of prognostic factors in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and chemotherapy. Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:78–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiorns LR, Swansbury GJ, Mehta J, Min T, Dainton MG, Treleaven J, Powles RL, Catovsky D. Additional chromosome abnormalities confer worse prognosis in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:314–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.d01-2037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mrozek K, Marcucci G, Nicolet D, Maharry KS, Becker H, Whitman SP, Metzeler KH, Schwind S, Wu YZ, Kohlschmidt J, Pettenati MJ, Heerema NA, Block AW, Patil SR, Baer MR, Kolitz JE, Moore JO, Carroll AJ, Stone RM, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD. Prognostic significance of the European LeukemiaNet standardized system for reporting cytogenetic and molecular alterations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:4515–4523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Padilha SL, Souza EJ, Matos MC, Domino NR. Acute myeloid leukemia: survival analysis of patients at a university hospital of Parana. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2015;37:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bjhh.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]