SUMMARY

SETTING

Few studies have shown the operational feasibility, safety, tolerability, or outcomes of multi-drug-resistant latent tuberculous infection (MDR LTBI) treatment. After two simultaneous multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) outbreaks in Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, infected contacts were offered a 12-month fluoroquinolone (FQ) based MDR LTBI treatment regimen.

DESIGN

Between January 2009 and February 2012, 119 contacts of MDR-TB patients were followed using a prospective observational study design. After MDR-TB disease was excluded, 12 months of daily FQ-based preventive treatment of MDR LTBI was provided by directly observed therapy.

RESULTS

Among the 119 infected contacts, 15 refused, while 104 began treatment for MDR LTBI. Of the 104 who initiated treatment, 93 (89%) completed treatment, while 4 contacts discontinued due to adverse effects. None of the 104 contacts who undertook MDR LTBI treatment of any duration developed MDR-TB disease; however, 3 of 15 contacts who refused and 15 unidentified contacts developed MDR-TB disease.

CONCLUSION

Providing treatment for MDR LTBI can be accomplished in a resource-limited setting, and contributed to preventing MDR-TB disease. The Chuuk TB program implemented treatment of MDR LTBI with an 89% completion rate. The MDR LTBI regimens were safe and well tolerated, and no TB cases occurred among persons treated for MDR LTBI.

Keywords: multidrug-resistant TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, TB prevention

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), defined as TB caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to at least isoniazid (INH) and rifampin (RMP), threatens communities throughout the world. MDR-TB prevalence is increasing, with some countries reporting over 20% MDR-TB among new TB cases.1 To compound the situation, only 48% of individuals with MDR-TB receive adequate treatment by international standards. Worldwide, MDR-TB mortality remains high, as 11–20% of treated individuals and 25–40% of untreated individuals die of the disease.2–5

Although MDR-TB strains of M. tuberculosis were thought to be less transmissible,5,6 person-to-person transmission resulting in primary MDR-TB disease in contacts has been well demonstrated.7,8 Rapid identification, isolation, and appropriate treatment of patients with infectious MDR-TB is essential to cure disease and interrupt further transmission. However, the appropriate management of infected MDR-TB contacts is less clear. INH and RMP, the standard treatment for drug-susceptible latent tuberculous infection (LTBI), are likely ineffective against MDR-TB strains.

To prevent progression to TB disease, several experts recommend that persons with LTBI undergo treatment based on the susceptibility results of the source case.9–11 Fluoroquinolones (FQs) are highly effective against drug-resistant M. tuberculosis and are often recommended in combination with other medications.9 However, some FQ-based combination MDR LTBI treatment regimens have been poorly tolerated.11–13 Furthermore, animal studies have suggested adverse effects on bone and cartilage development, resulting in a reluctance to use FQs in pediatric patients.14 MDR-TB experts have suggested that the benefits of using FQs outweigh the risks when treating pediatric MDR-TB patients or treating MDR-TB contacts for LTBI (MDR LTBI).15,16 As studies reporting MDR-TB outcomes have focused on TB disease,17–19 previous articles have highlighted the need for studies to demonstrate tolerability, feasibility, safety and efficacy of treatment for MDR LTBI.20

We describe our experience in providing MDR LTBI treatment following two simultaneous MDR-TB outbreaks in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). Our study followed the treatment of contacts with LTBI after exposure to infectious MDR-TB patients. The purpose of the study was to describe the tolerability and safety of the FQ-based regimens, to examine the operational feasibility of LTBI treatment in a resource-poor setting, and to observe whether treatment lowered the risk of progression to TB disease.

METHODS

FSM is an independent country located in the Western Pacific that is affiliated with the United States by a Compact of Free Association. Chuuk is the largest of the FSM states, with a population of 55 000. In 2007, TB incidence in Chuuk was 127 cases per 100 000 population, 30-fold higher than the US rate (4.4/ 100 000).21 The first documented MDR-TB case in Chuuk was reported in December 2007. By June 2008, without access to second-line anti-tuberculosis medications, a total of five cases of MDR-TB had been diagnosed and four had died. In July 2008, an investigation found evidence of two MDR-TB outbreaks with ongoing transmission among household contacts.22

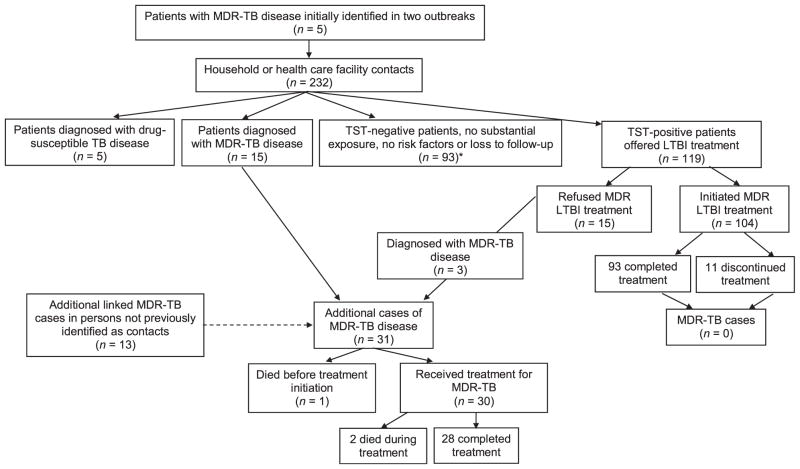

From patient and family interviews, the investigation identified 232 household or health care facility contacts (Figure 1). Household contacts were defined as persons who had spent at least one night in the same household as an infectious MDR-TB patient. Health care facility contacts were defined as either having provided direct health care services or having performed a medical procedure on a MDR-TB patient. LTBI among these contacts was diagnosed using the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST) using ≥ 5 mm as cut-off. Excluding 20 contacts who were subsequently diagnosed with TB disease, 119 MDR-TB contacts had evidence of LTBI and were offered treatment with FQ-based regimens.23

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of screening and results of investigation, Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012. MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant TB; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test: LTBI = latent tuberculous infection.

All contacts were carefully evaluated using symptom review, clinical examination, and chest X-ray (CXR) before initiating treatment. Contacts were offered treatment with one of four FQ-based regimens tailored to the contact’s age and the source-case isolate drug susceptibility testing (DST) result. The regimens were those recommended by the MDR-TB Expert Network (Table 1). Health care workers exposed to multiple MDR-TB patients were included in the five-drug resistant group. Treatment for MDR LTBI was given by daily directly observed therapy (DOT) for 12 months. In some villages, weekend doses were self-administered. Monthly compensation (US$5) was provided to contacts who completed 90% of expected doses.

Table 1.

Treatment regimens for MDR LTBI, Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012*

| Source patient isolate | MDR LTBI treatment regimen |

|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis resistant to INH, RMP and ETH | Adults aged >12 years: MFX 400 mg by mouth daily and EMB 15 mg/kg by mouth daily for 12 months Children aged ≤12 years: LVX 20 mg/kg by mouth daily and EMB 15 mg/kg by mouth daily for 12 months |

| M. tuberculosis resistant to INH, RMP, PZA, EMB and SM | Adults aged >12 years: MFX 400 mg by mouth daily for 12 months Children aged ≤12 years: LVX 20 mg/kg by mouth daily and ETH 20 mg/kg by mouth daily for 12 months |

Regimens were recommended by the MDR-TB Expert Network, a group of US national TB experts who convene every 2 months to offer expert opinion on the treatment and management of challenging drug-resistant cases.

MDR=multidrug-resistant; LTBI=latent tuberculous infection; INH=isoniazid; RMP=rifampin; ETH=ethionamide; MFX=moxifloxacin; EMB=ethambutol; LVX= levofloxacin; PZA = pyrazinamide; SM = streptomycin.

This study presents a prospective observational cohort design following MDR-TB contacts from January 2009 to February 2012. Study participants provided written informed consent for data collection. Demographic information, history of TB exposure, clinical data (weight, TB symptom screening, bacille Calmette-Guérin status, comorbidities) and CXR findings were abstracted onto data collection forms. For contacts aged ≥18 years, baseline comorbidities were assessed by measuring random glucose to detect diabetes mellitus (DM),24 serum hepatic aminotransferase levels and rapid testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection using oral specimens. For contacts aged <18 years, parents or guardians were interviewed to determine a history of HIV infection or DM. No baseline laboratory tests were performed for contacts aged <18 years.

Community workers recruited from communities affected by the MDR-TB outbreaks underwent training in performing DOT and assessing for adverse effects. For each contact, a monthly summary of DOT adherence and adverse-effect data were collected by the TB program. Contacts were evaluated by a clinician at 3-month intervals, with CXR performed at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after initiation of treatment. If indicated, sputum samples or gastric aspirates were collected in the treatment or post-treatment monitoring period.

Treatment completion was defined as taking 80% of doses under DOT (292/365 doses) within 15 months.25,26 Treatment interruption was defined as missing medications for >2 consecutive weeks. Discontinued treatment was defined as >2 months of consecutively missed doses. The occurrence of adverse effects was reported as person-months, as individualized adverse effect data were recorded monthly for each of the 12 months. Routine blood testing was not required for contacts who did not report adverse effects.

Data were entered into Epi-Info 3.5 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA). Bivariate analyses for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables were performed using SAS 9.2 (Statistical Analysis Software Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to demonstrate differences in treatment outcomes; ORs that excluded the 1.0 null value in their 95% confidence interval (CI) were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA, before the study was undertaken. The FSM Department of Health approved the protocol and deferred IRB approval to CDC.

RESULTS

Of the 119 contacts with MDR LTBI, 104 (87%) initiated treatment and 15 (13%) refused treatment or discontinued treatment within 2 weeks. The median age of those who began treatment was 24 years (range 1–62) (Table 2). The 15 contacts who refused were older (median age 32 years), but were otherwise similar to those who initiated treatment. Of the 104 contacts who began treatment, none was reported to be HIV-infected.

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of infected contacts who initiated treatment for LTBI, by source MDR-TB patient, Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012

| Demographic characteristic | Source MDR-TB case

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 104) n (%) |

Resistant to five drugs (n = 63) n (%) |

Resistant to three drugs (n = 41) n (%) |

|

| Age, years | |||

| <5 | 6 (6) | 4 (6) | 2 (5) |

| 5–11 | 20 (19) | 10 (16) | 10 (24) |

| 12–17 | 17 (16) | 6 (9) | 11 (27) |

| 18–25 | 17 (16) | 10 (16) | 7 (17) |

| 26–40 | 14 (14) | 9 (15) | 5 (12) |

| 41–55 | 17 (16) | 14 (22) | 3 (7) |

| >55 | 13 (12) | 10 (16) | 3 (7) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 48 (47) | 28 (44) | 20 (49) |

| Female | 56 (53) | 35 (56) | 21 (51) |

| HIV infection* | |||

| Adults tested | 61 (55) | 29 (47) | 15 (37) |

| Pediatric (assessed by patient history) | 43 (45) | 34 (53) | 26 (63) |

| Diabetes mellitus† | |||

| Adults testing positive | 9 (9) | 7 (11) | 2 (5) |

No individuals tested positive for HIV.

Diabetes mellitus screening using random glucose. Values ≥200 mg/dl indicated diabetes mellitus.26

LTBI =latent tuberculous infection; MDR-TB =multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; HIV =human immunodeficiency virus.

Because of the known increased risk of progression from infection to TB disease in patients with DM, all adults were screened using random glucose levels. Nine of the 61 adult contacts reported a history of DM, and the remaining 52 adult contacts had random blood glucose levels that were not indicative of DM (<200 mg/dl) at baseline screening. None of the children had DM according to medical history.

DOT workers compiled missed doses and adverse effect occurrences in their monthly reports for each contact. Over the 12-month treatment regimen, the 104 contacts had the opportunity to report adverse effects during 1248 person-months (p-m). The number of monthly reports available for abstraction was 1038 (83%). Table 3 shows the outcomes of contacts who began treatment for LTBI by regimen and age. Overall, 93 (89%) of the 104 contacts completed LTBI treatment. Of 26 contacts aged <12 years, 25 (96%) completed treatment.

Table 3.

Treatment completion rate for MDR-TB contacts by age and regimen, Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012

| Patients who started treatment n |

Patients who completed treatment n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| <5 | 6 | 6 (100) |

| 5–11 | 20 | 19 (95) |

| 12–17 | 17 | 17 (100) |

| 18–25 | 17 | 14 (82) |

| 26–40 | 14 | 11 (73) |

| 41–55 | 17 | 15 (88) |

| >55 | 13 | 11 (85) |

| Total | 104 | 93 (89) |

| Treatment regimen | ||

| MFX only | 46 | 36 (83) |

| MFX + EMB | 24 | 21 (88) |

| LVX only* | 5 | 5 (100) |

| LVX + EMB | 17 | 16 (94) |

| LVX + ETH | 12 | 12 (100) |

| Total | 104 | 93 (89) |

Four patients who began treatment with MFX alone received <6 months of MFX before completing the remainder of treatment with LVX only. These four patients are included in the LVX only group.

MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; MFX = moxifloxacin; EMB = ethambutol; LVX = levofloxacin; ETH = ethionamide.

Of the 93 contacts who completed treatment over 1 year, the median number of missed doses was 3.5. Five of the 93 patients experienced interruptions (>30 days) in treatment—one due to pregnancy, and four due to adverse effects. After clinical evaluation, all five were able to restart and complete treatment within 15 months. For the four adult contacts who interrupted treatment due to adverse effects, substituting levofloxacin (LVX) 500 mg daily for moxifloxacin (MFX) 400 mg daily resulted in treatment completion.

Among the 11 contacts (11%) who initiated but did not complete LTBI treatment, five contacts on MFX-based regimens discontinued for personal reasons, such as travel for extended periods of time and emigration. Another two women discontinued treatment after becoming pregnant, and declined to reinitiate. The remaining four contacts discontinued due to adverse effects. Three health care workers on MFX monotherapy discontinued treatment, two due to nausea or other gastrointestinal disturbances, and one with muscle and joint pain. The fourth discontinuation occurred in an 8-year-old child after symptoms of hepatitis were noted; serum hepatic aminotransferase levels were elevated. Acute hepatitis A was confirmed by serologic testing, but the patient did not resume LTBI treatment after the hepatitis resolved.

No serious adverse events, defined as hospitalization or irreversible morbidity, were attributed to the 12-month FQ-based regimens in either the adult or pediatric contacts. Fifty-six (53%) contacts reported at least one adverse effect during MDR LTBI treatment. Only 16 contacts (15%) reported adverse effects more than three times during the 12-month treatment period. Overall, adverse effects were reported during 15% (159/1038) of p-m.

Table 4 shows the frequency of each reported adverse effect. Nausea was the most common, reported by 35 contacts during 112 p-m. In addition, dizziness/headache, fatigue and muscle/joint pain (72, 22, and 21 p-m, respectively) were reported. These adverse effects were primarily reported by contacts taking FQ monotherapy (Table 5). Excluding children aged <12 years (none of whom were on MFX-based regimens), the odds of reporting any adverse effects over the course of treatment were 3.8 times higher (95%CI 1.2–9.2) among contacts on MFX monotherapy compared to adults taking other regimens. Among adults only, the odds of reporting adverse effects at any point during the 12-month regimen were lower for those taking MFX and ethambutol (EMB) compared with contacts taking other regimens (OR 0.3, 95%CI 0.1–0.8). Completion rates for both groups were the same (83% vs. 88%, OR 1.9, 95%CI 0.5–7.7). When compared with other adult contacts, the odds of reporting adverse effects were significantly higher among health care workers (OR 5.5, 95%CI 1.8–17).

Table 4.

Adverse effects reported by contacts during MDR LTBI treatment, Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012

| Adverse effect | Adverse effects, number of contacts (n = 104)* n (%) |

Adverse effects, person-months (n = 1038)† n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 35 (33) | 112 (10.8) |

| Dizziness/headache | 26 (25) | 72 (6.9) |

| Fatigue | 16 (15) | 22 (2.1) |

| Muscle and joint pain | 10 (9) | 21 (2.0) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (8) | 10 (1.0) |

| Jaundice | 1 (1)‡ | 1 (0.1) |

This table includes all contacts who initiated treatment, including those who discontinued treatment.

Contacts could report more than one adverse effect each month.

Laboratory-confirmed concomitant acute hepatitis A infection.

MDR = multidrug-resistant; LTBI = latent tuberculous infection.

Table 5.

Tolerability of treatment for infected contacts by age, person-months, Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012

| Regimen | Person-months n |

None n (%) |

Neurologic* n (%) |

Gastro-intestinal† n (%) |

Musculo-skeletal‡ n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects in adult contacts (18–49 years) | |||||

| Total | 578 | ||||

| MFX | 392 | 288 (73) | 24 (6) | 72 (18) | 8 (2) |

| LVX§ | 22 | 16 (73) | 3 (14) | 2 (9) | 1 (4) |

| MFX+EMB | 164 | 152 (94) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Adverse effects in pediatric contacts (0–17 years) | |||||

| Total | 460 | ||||

| MFX | 31 | 18 (58) | 3 (10) | 4 (13) | 1 (3) |

| LVX§ | 23 | 21 (91) | 0 | 2 (9) | 0 |

| MFX+EMB | 71 | 67 (94) | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (3) |

| LVX+EMB | 200 | 197 (99) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| LVX+ETH | 135 | 114 (84) | 2 (1) | 16 (13) | 3 (2) |

Includes headache, dizziness, or visual disturbances.

Includes nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or jaundice.

Includes tendon or joint pain, or generalized fatigue.

Four patients who began treatment with MFX only, received <6 months of MFX before completing the remainder of treatment with LVX only. These four patients are included in the LVX only group.

MFX = moxifloxacin; LVX = levofloxacin; EMB = ethambutol; ETH = ethionamide.

After 36 months of follow-up, none of the 104 contacts who completed MDR LTBI treatment developed TB disease. Among the 11 contacts who discontinued MDR LTBI treatment, none had progressed to TB disease at 36 months follow-up. Six of these contacts took their medications for more than 6 months.

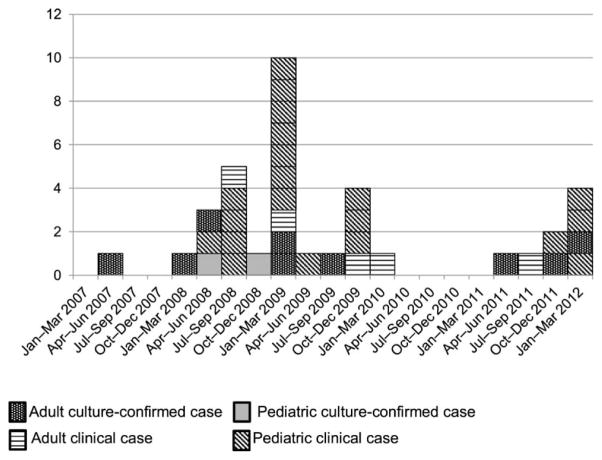

Among the 15 contacts who refused LTBI treatment, three (20%) developed MDR-TB disease (Figure 1). Fifteen contacts were diagnosed with MDR-TB disease before treatment for LTBI could be offered. A final 13 persons not initially identified as contacts or lost to follow-up were diagnosed with MDR-TB disease, resulting in a total of 31 additional patients since the initial July 2008 investigation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MDR-TB outbreak cases (n =36), Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia, 2009–2012. MDR-TB = multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

The experience of treating MDR LTBI in Chuuk adds important information to the sparse data on strategies to manage contacts exposed to patients with infectious MDR-TB. Management of MDR-TB contacts is challenging in any setting, but resource-poor settings must overcome even more challenges, as they often lack reliable diagnostic tools, laboratory services, and adequate facilities to provide treatment and expert consultation in the management of complicated patients.10,12 Despite substantial infrastructure challenges,27 the Chuuk State TB Program has demonstrated that treatment of contacts of patients with MDR-TB is feasible.

Despite several statistically significant differences in reported adverse events between various regimens, the observed overall completion rate was excellent. Distinctions in tolerability may be intrinsic to various regimens, but more likely differ due to patient selection (pediatric vs. adult), variability in DOT worker reporting, and variations in cultural attributes among families exposed to MDR-TB.

Numerous factors contributed to the high rate of treatment completion in Chuuk. DOT workers were recruited from the affected communities and several trusted clinicians led community education efforts among community leaders, patients, and families.27 These outreach activities established confidence in the TB program and increased the acceptability of recommendations for treatment of MDR LTBI. Finally, compensation ($5/month) was provided to each contact who completed ≥90% of treatment, which possibly contributed to high rates of adherence with treatment.

With careful monitoring, treatment of MDR LTBI was safe and well tolerated. DOT workers were trained to recognize medication adverse effects during their daily interactions with patients. After 3 years of clinical follow-up, there was no evidence of serious adverse events from the various 12-month FQ-based regimens used to treat MDR LTBI.

Our prospective observational study design was intended to describe operational feasibility, tolerability, and treatment outcomes rather than efficacy. The study design did not allow a definitive statement to be made regarding efficacy for preventing progression to TB disease. However, after 3 years of monitoring, none of the contacts who completed MDR LTBI treatment regimens developed MDR-TB disease. Furthermore, the finding of 31 additional patients with MDR-TB disease among contacts who did not take treatment suggests an important protective benefit of treating MDR LTBI.

In a survey of 35 countries with >2% incident MDR-TB, only 11 had written policies on how to manage MDR-TB contacts and only three made an effort to treat contacts. The most commonly cited reason for not having policies was lack of data or guidance.28 Unfortunately, lack of data on MDR-TB disease transmission has led to continued skepticism about the need to treat MDR-TB contacts.20 Measurement of the efficacy of MDR LTBI treatment is needed and should be a priority for future research.

This study presents several limitations. The most important limitation was that the observational design did not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn regarding efficacy. Second, as four of five initial MDR-TB patients died, contact investigations were conducted through proxy interviews.22 Despite concerted efforts to find all possible contacts, 13 patients with significant exposure to infectious MDR-TB cases were not identified in the initial contact investigations, and later developed MDR-TB disease without being offered MDR LTBI treatment. It is likely that additional unidentified contacts did not develop MDR-TB disease despite not receiving MDR LTBI treatment. A proper estimation of efficacy would require knowing the total number of individuals within the Chuukese community who were exposed to, but did not develop, MDR-TB disease.

With aggressive case finding, effective isolation, and treatment of patients hospitalized with infectious MDR-TB,27 there was little risk of MDR-TB reinfection among contacts in Chuuk. Some of the apparent reported ineffectiveness of LTBI regimens in previous studies may be due to high rates of MDR-TB reinfection in high-burden settings.28,29

MDR-TB will continue to be a substantial public health problem, even with excellent DOT, uninterrupted supplies of second-line medications, quality laboratory facilities, and public health support. When new MDR-TB cases arise, the highest priority must be the rapid identification, isolation, and appropriate treatment of patients with infectious MDR-TB.30 However, after this priority has been addressed, the identification and treatment of infected contacts represent an important opportunity for preventing additional MDR-TB within communities.

The effort to treat MDR LTBI in Chuuk has proved feasible for the local TB program, tolerable and safe for contacts, and potentially life-saving for the broader community. The described success of this program may serve as guidance for other programs implementing MDR LTBI treatment activities, and may inform future guidelines and policies for the treatment of contacts of MDR-TB patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Chuukese patients for their continued resilience over the last 5 years. The Chuuk State TB Program is staffed by dedicated clinicians, DOT workers, and administrative staff who have worked tirelessly to keep their communities healthy. The political will and tireless support shown by the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) national government must also be mentioned. Many experts have contributed to this study; we would like to acknowledge in particular R Wada, M Ekiek, C Wassem, S Althomsons, M Bankowski, A Buff, E Desmond, M Haddad, K Ijaz, G Lin, A Loeffler, J Marar, K Powell, P Talboy, V Skilling, and C Ying.

The Chuuk State TB Program, US Department of Interior—Compact of Free Association (Washington DC, USA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA) and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (Saipan, FSM) all provided funds for travel of researchers to FSM during the outbreak investigation and during follow-up visits to complete the study. Only Chuuk State TB Program and the CDC contributed funds toward data collection, analysis and the preparation of the manuscript.

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the CDC.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orenstein EW, Basu S, Shah S, et al. Treatment outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:153–161. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falzon D, Gandhi N, Migliori GB, et al. Resistance to fluoroquinolones and second-line injectable drugs: impact on multidrug-resistant TB outcomes. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:156–168. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00134712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnston JC, Shahidi NC, Sadatsafavi M, Fitzgerald JM. Treatment outcomes of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2009;4:e6914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Soolingen D, Borgdorff MW, de Haas PE, et al. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in the Netherlands: a nationwide study from 1993 through 1997. JInfect Dis. 1999;180:726–736. doi: 10.1086/314930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandjean L, Crossa A, Gilman RH, et al. Tuberculosis in household contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients. Int JTuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1164–1169. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vella V, Racalbuto V, Guerra R, et al. Household contact investigation of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting. Int JTuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1170–1175. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iseman M. Treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. NEngl J Med. 1993;329:784–791. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309093291108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan ED, Iseman M. Current medical treatment for tuberculosis. BMJ. 2002;325:1282–1286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridzon R, Kent JH, Valway S, et al. Outbreak of drug-resistant tuberculosis with second-generation transmission in a high school in California. J Pediatr. 1997;131:863–868. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diel R, Loddenkemper R, Zellweger JP, et al. European Forum for TB Innovation. Old ideas to innovate tuberculosis control: preventive treatment to achieve elimination. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:785–801. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00205512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridzon R, Meader J, Maxwell R, et al. Asymptomatic hepatitis in persons who received alternative preventive therapy with pyrazinamide and ofloxacin. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1263–1264. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.6.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn DL, Hewlett D, Alfalla C, Peterson S, Opal SM. Limited tolerance of ofloxacin and pyrazinamide prophylaxis against tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1241. doi: 10.1056/nejm199404283301718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noel GJ, Bradley JS, Kauffman RE, et al. Comparative safety profile of levofloxacin in 2523 children with a focus on four specific musculoskeletal disorders. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:879–891. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3180cbd382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passannante MR, Gallagher CT, Reichman LB. Preventative therapy for contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Chest. 1994;106:431–434. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickwell SM. Positive PPD and chemoprophylaxis for tuberculosis infection. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1929–1934. 1937–1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freier G, Wright A, Nelson G, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in military recruits. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:760–762. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi N, Moll A, Sturm AW, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006;368:1575–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Deun A, Maug AK, Salim MA, et al. Short, highly effective, and inexpensive standardized treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:684–692. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0077OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Werf MJ, Langendam MW, Sandgren A, Manissero D. Lack of evidence to support policy development for management of contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients: two systematic reviews. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:288–296. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported TB in the United States, 2008: TB surveillance report. Atlanta, GA, USA: CDC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Two simultaneous outbreaks of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis – Federated States of Micronesia, 2007–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:253–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;41(RR-11):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Publication No. 09–4642. Bethesda, MD, USA: NIH; 2008. Diagnosis of diabetes. National Diabetes Information Clearninghouse. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menzies D, Dion MJ, Rabinovitch B, Mannix S, Brassard P, Schwartzman K. Treatment completion and costs of a randomized trial of rifampicin for 4 months versus isoniazid for 9 months. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:445–449. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-478OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seaworth B. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2002;16:73–105. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(03)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brostrom R, Fred D, Heetderks A, et al. Islands of hope: building local capacity to manage an outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the Pacific. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:14–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cain KP, Nelson LJ, Cegielski JP. Global policies and practices for managing persons exposed to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaaf HS, Gie RP, Kennedy M, Beyers N, Hesseling PB, Donald PR. Evaluation of young children in contact with multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis: a 30-month follow-up. Paediatrics. 2002;109:765–771. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor Z, Nolan CM, Blumberg HM. Controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Recommendations from the American Thoracic Society, CDC, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-12):1–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]