Abstract

Animals and plants are increasingly threatened by emerging fungal and oomycete diseases. Amongst oomycetes, Saprolegnia species cause population declines in aquatic animals, especially fish and amphibians, resulting in significant perturbation in biodiversity, ecological balance and food security. Due to the prohibition of several chemical control agents, novel sustainable measures are required to control Saprolegnia infections in aquaculture. Previously, fungal community analysis by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) revealed that the Ascomycota, specifically the genus Microdochium, was an abundant fungal phylum associated with salmon eggs from a commercial fish farm. Here, phylogenetic analyses showed that most fungal isolates obtained from salmon eggs were closely related to Microdochium lycopodinum/Microdochium phragmitis and Trichoderma viride species. Phylogenetic and quantitative PCR analyses showed both a quantitative and qualitative difference in Trichoderma population between diseased and healthy salmon eggs, which was not the case for the Microdochium population. In vitro antagonistic activity of the fungi against Saprolegnia diclina was isolate-dependent; for most Trichoderma isolates, the typical mycoparasitic coiling around and/or formation of papilla-like structures on S. diclina hyphae were observed. These results suggest that among the fungal community associated with salmon eggs, Trichoderma species may play a role in Saprolegnia suppression in aquaculture.

Keywords: salmon, Saprolegniosis, Microdochium, Trichoderma

1. Introduction

Saprolegniosis, caused by Saprolegnia species, results in tremendous losses in wild and cultured fish species including salmonids such as salmon and trout, and non-salmonids such as tilapia, catfish, carp, and eel [1]. The typical symptoms of Saprolegniosis are white or grey fungal-like hyphal mats on fish or their eggs [2]. Yield losses of 10% to more than 50% have been reported in eggs and young fish [1,3,4].

To control Saprolegniosis, formalin is now commonly applied but is expected to be banned soon due to adverse effects on the environment [1]. A limited number of chemical and non-chemical alternative treatments have been tested to control Saprolegniosis, including hydrogen peroxide, sea water flushes and ultraviolet irradiation, but none of these are as effective as the banned malachite green [1]. Also, no vaccine is currently available to control this disease [1,5].

Bacterial genera such as Bacillus, Enterococcus and Lactobacillus have been shown to reduce specific diseases in aquaculture and several of these beneficial bacteria are being commercialized [6,7,8,9,10]. As a sustainable measure to combat Saprolegniosis, the bacterial genera Aeromonas, Frondihabitans and Pseudomonas have been proposed [1,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Alike the probiotic bacteria, several beneficial fungi and/or their bioactive compounds are applied to control diseases. These fungal species are isolated either randomly or systematically [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Amongst commercialized fungi, Aspergillus oryzae, Coniothyrium minitans, Phlebiopsis gigantea and Trichoderma (teleomorph Hypocrea [26]) spp., are able to suppress diseases and promote the growth of various hosts, mainly terrestrial crops and some animals such as cattle [27,28,29,30]. For fish, Trichoderma viride enhanced body weight and reduced mortality of Nile tilapia exposed to Saprolegnia sp. [31]. The commercial product HetroNex, containing Trichoderma viride and Trichoderma harzianum, has been developed to control fungal and oomycete diseases caused by Fusarium, Lagenidium and Saprolegnia in aquaculture ponds of fish, prawn and shrimp [32].

In a fungal diversity study of the marine sponge Dragmacidon reticulatum, Trichoderma represented one of the most abundant genera among the isolated fungi [33]. To date, however, still little is known about the fungal community in aquaculture or aquatic environments [18,34]. Previously, we showed by clone library analyses that the oomycete community associated with Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) and healthy salmon eggs from a commercial fish hatchery were dominated by Saprolegnia with no difference in the number and pathogenicity of the Saprolegnia isolates present in either diseased or healthy salmon egg batches [18]. Based on terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis and clone library sequencing, also no obvious differences were observed in the fungal community composition between the diseased and healthy salmon egg batches [18]. The clone library consisted of 209 fungal clones, the majority of which belonged to the Ascomycota. More specifically, 139 clones were classified as Microdochium (teleomorph Monographella) [18,35,36]. To elucidate the role of fungi in the protection of salmon eggs against Saprolegniosis, we isolated and (phylogenetically) characterized fungi from diseased and healthy salmon eggs. Their abundance in diseased and healthy salmon egg batches and their activity against Saprolegnia diclina were investigated here.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Isolation of Fungi from Diseased and Healthy Salmon Eggs

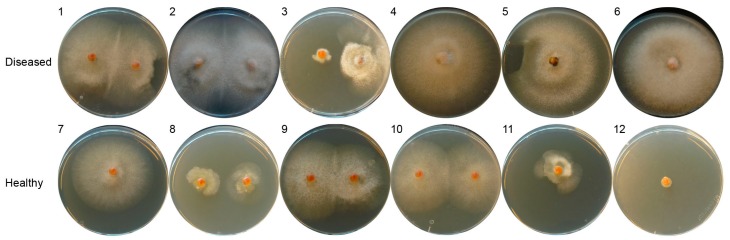

Previously, Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) and healthy salmon eggs and their corresponding incubation water were sampled from a commercial fish farm (N = 6 for diseased eggs and N = 6 for healthy eggs) [18]. Per sample, one or two salmon eggs were placed on potato dextrose agar to allow fungal outgrowth (Figure 1). We obtained and purified 20 fungal isolates in total and by ITS sequencing identified three different genera, Microdochium, Trichoderma (both Ascomycota) and Mortierella (Zygomycota). Microdochium and Mortierella were the most represented genera in our previous clone library sequence analysis. Interestingly, Trichoderma was not detected in the previous analysis, probably due to the limited number of sequenced clones, the specificity of the primers or the efficiency of the PCR reaction [18]. The two Mortierella isolates (BLAST identity of 100% in Genbank database) were isolated from only one healthy salmon egg sample. Here we aimed at comparing isolates obtained from multiple replicate samples of diseased and healthy eggs. Therefore, we focused on the Ascomycota isolates for the subsequent analyses described below.

Figure 1.

Isolation of salmon egg-associated fungi and oomycetes on potato dextrose agar plates. One or two salmon eggs from a Saprolegnia-infected batch (diseased, replicate No. 1–6) or a healthy batch (replicate No. 7–12) were placed onto the agar plates to allow fungal outgrowth.

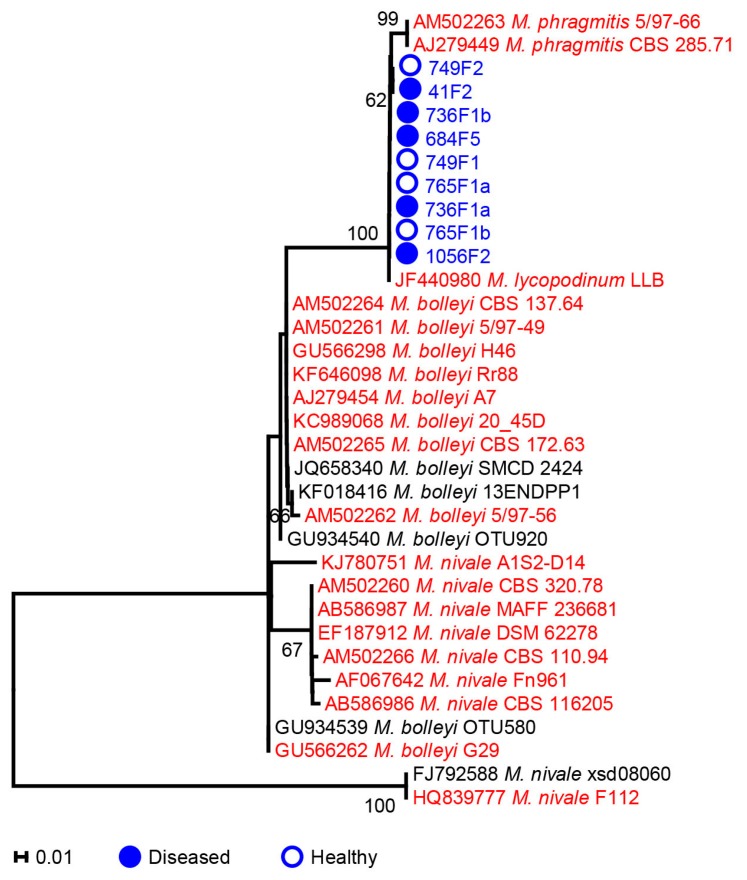

2.2. Microdochium

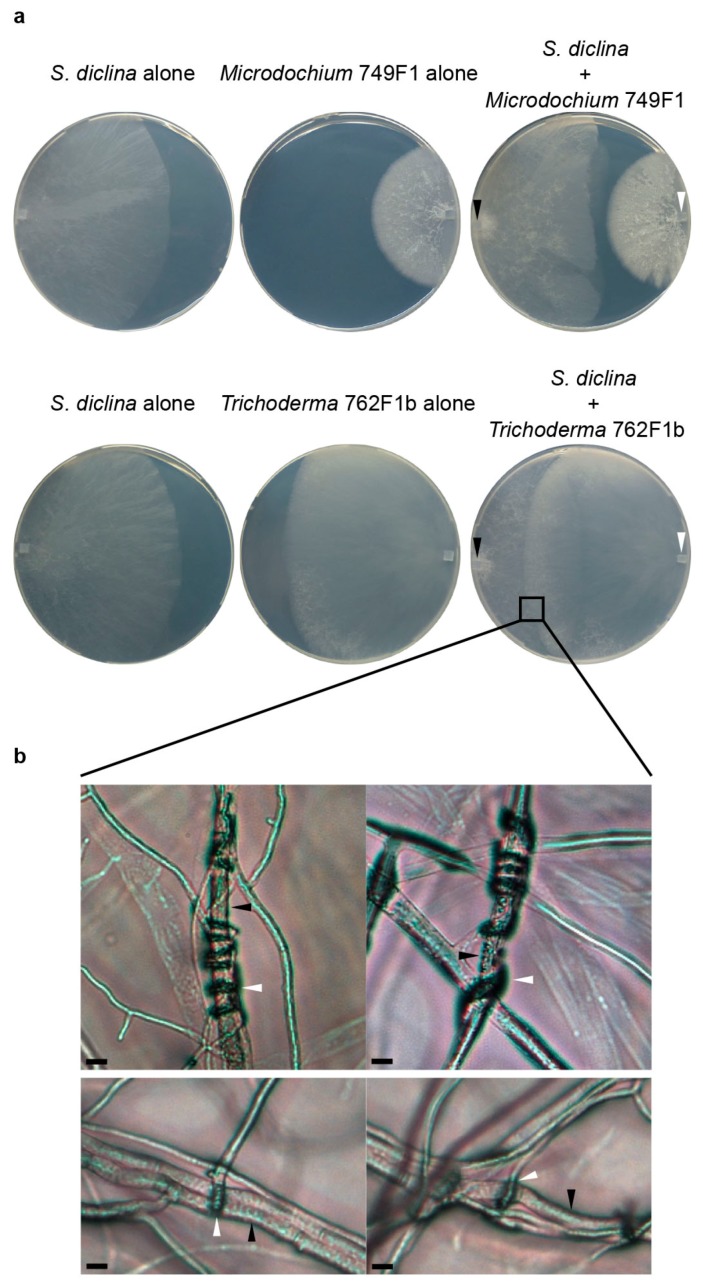

Microdochium species are known as snow molds, and some are pathogenic to plants [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Microdochium nivale and Microdochium majus are two of the main causative agents of Fusarium head blight [42], whereas Microdochium lycopodinum and Microdochium phragmitis were isolated from plants without causing disease [45,46]. M. phragmitis was endophytic in common reed and was more present in flooded habitats than the closely related Microdochium bolleyi [45]. Some Microdochium species were antagonistic to the plant pathogen Verticillium dahliae [47]. Amongst our nine Microdochium isolates, five were isolated from diseased and four from healthy salmon eggs (Table 1). The origin of our Microdochium isolates was possibly from the catchment area, which was the water source for the salmon egg incubators [18]. Based on the phylogenetic analyses of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, all the nine Microdochium isolates are closely related to M. lycopodinum and M. phragmitis, and no distinct separation is observed between isolates from diseased or healthy salmon eggs (Figure 2). Quantitative PCR using M. lycopodinum/M. phragmitis specific primers showed and confirmed that M. lycopodinum/M. phragmitis was detected in equal amounts in total DNA samples obtained from diseased and healthy salmon egg samples (Figure 3). One Microdochium isolate (749F1) inhibited the hyphal growth of Saprolegnia diclina on 1/5th strength potato dextrose agar (1/5PDA) (Table 1, Figure 4a) suggesting the secretion of enzymes or other bioactive metabolites.

Table 1.

In vitro activity of Microdochium or Trichoderma isolates against hyphal growth of Saprolegnia diclina 1152F4. The fungal isolates were retrieved from Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) or healthy salmon egg samples.

| Genus | Strain No. | Salmon Egg Sample | Activity of Culture Filtrate | Dual Culture Assay on 1/5PDA | Hyphal Interaction with S. diclina Microscopically |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microdochium | 41F2 | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed |

| 684F5 | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 736F1a | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 736F1b | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 1056F2 | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 765F1a | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 765F1b | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 749F1 | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Inhibitory | Not observed | |

| 749F2 | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Not observed | |

| Trichoderma | 684F1 | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Coiling, papilla-like structure |

| 1056F1 | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Papilla-like structure | |

| 1152F1 | Diseased | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Inconclusive | |

| 762F1a | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Coiling | |

| 762F1b | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Coiling | |

| 762F2 | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Papilla-like structure | |

| 764F1 | Healthy | Inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Papilla-like structure | |

| 764F2 | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Coiling, papilla-like structure | |

| 764F3 | Healthy | Not inhibitory | Not inhibitory | Coiling, papilla-like structure |

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of ITS rRNA sequences of nine Microdochium isolates from salmon eggs and reference strains. The phylogenetic analyses were conducted in Mega 5 using the Kimura 2-parameter method [48] to compute evolutionary distances. The bootstrap values indicated at the nodes are based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branch values lower than 50% are hidden. Closed and open circles indicate Microdochium isolates from Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) or healthy salmon egg samples, respectively. Red, blue and black colors indicate strains from terrestrial/plant, aquatic and unknown sources of isolation, respectively. The scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.01 nucleotide substitution per sequence position. Twenty-five ITS sequences of good quality and at least 550 bp of reference strains of Microdochium were downloaded from GenBank; their strain names are preceded by the accession numbers.

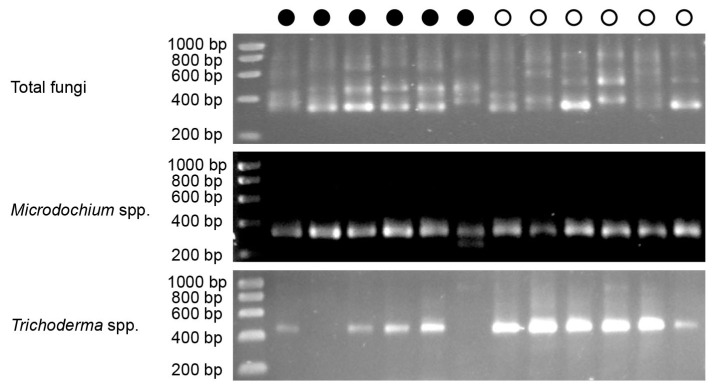

Figure 3.

Detection of total fungi, Microdochium and Trichoderma in salmon egg samples by quantitative PCR. Total fungal community was detected using ITS4-ITS9 primers, Microdochium lycopodinum/Microdochium phragmitis species were detected by MPF-MPR primers, and Trichoderma species were detected by ITS1TrF-ITS4TrR primers. The concentration of DNA template of each sample was normalized at 5 ± 1 ng·μL−1. Closed and open circles indicate DNA samples extracted from Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) or healthy samples, respectively. The lane on the left is the size marker and the band size (bp) is indicated next to each band.

Figure 4.

In vitro activities of Microdochium and Trichoderma isolates. (a) Dual culture of Microdochium isolate 749F1 or Trichoderma isolate 762F1b with Saprolegnia diclina 1152F4 on 1/5th strength potato dextrose agar (1/5PDA). S. diclina and the fungal isolates were pre-grown on 1/5PDA. A hyphal plug of S. diclina was inoculated on the left side of the fresh 1/5PDA and a hyphal plug of Microdochium isolate 749F1 or Trichoderma isolate 762F1b was inoculated on the right side. The dual cultures were incubated for six days at 20–25 °C. The black arrows indicate S. diclina plugs and the white arrows indicate Microdochium or Trichoderma plugs; (b) Microscopic pictures of the hyphal interaction between Trichoderma and S. diclina. The black arrows indicate hyphae of S. diclina. The white arrows indicate the coiling of Trichoderma hyphae around S. diclina hyphae (top pictures) or the formation of papilla-like structure of Trichoderma hyphae around S. diclina hyphae (bottom pictures). Scale bars represent 10 μm.

To date, not much is known about Microdochium in aquatic environments, aquaculture or aquatic animals [18]. Also not much is known about the bioactive compounds produced by Microdochium. Bhosale et al. (2011) reported that the active compound cyclosporine A, extracted from an estuarine M. nivale, has the potential to be applied pharmaceutically to control diseases caused by some dermatophytes and Aspergillus species in human and animals [49]; Santiago et al. (2012) reported that the extract of M. phragmitis, which was isolated from Antarctic angiosperms, showed cytotoxic activity against a human tumoral cell line [50]. Therefore, further experiments are needed to decipher the bioactive potential capacity of our Microdochium isolates, especially their interaction with pathogens from cold water environments, like Saprolegnia spp.

2.3. Trichoderma

Most Trichoderma species are applied in agriculture as biocontrol agents against various plant-associated bacterial, fungal and oomycete pathogens, such as Clavibacter, Fusarium and Phytophthora [26,51,52]. Trichoderma species are capable of producing a range of extracellular compounds to suppress plant pathogens, such as enzymes, fungicidal compounds and antibiotics; they can also promote plant growth via symbiotic association with plant hosts [26,51,53,54,55]. Trichoderma is commonly isolated from terrestrial environments, such as soil and wood [26], but also from aquatic environments like freshwater (drinking water) and marine water [33,56,57,58,59,60]. Marine Trichoderma atroviride and Trichoderma asperelloides suppressed disease caused by Rhizoctonia solani on beans and enhanced defence responses against pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae pv. Lachrimans on cucumber seedlings [57]. Some other marine-derived Trichoderma strains were capable of producing antagonistic compounds against cancer, diabetes, cancer cell lines or pathogenic Staphylococcus epidermidis; such compounds include tandyukisins from Trichoderma harzianum OUPS-111D-4, pyridones from Trichoderma sp. MF106, and trichoketides from Trichoderma sp. TPU1237 [58,61,62].

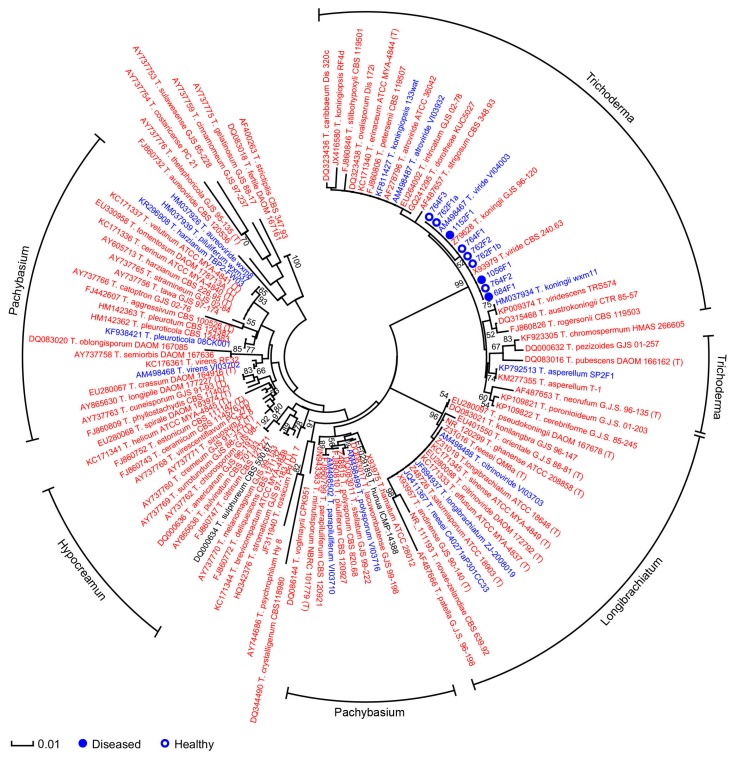

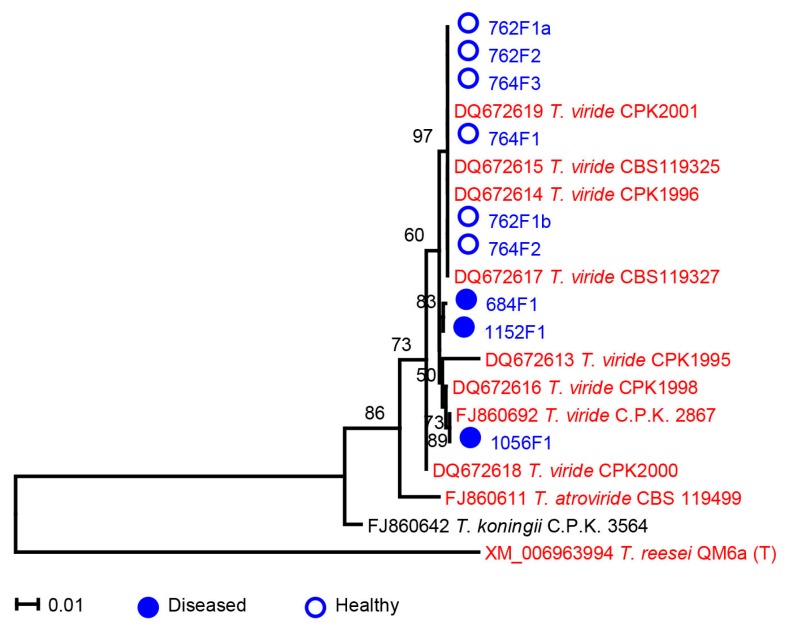

It was suggested that Trichoderma may have the potential to also control infectious diseases in aquaculture [63]. Among our nine Trichoderma isolates, three were isolated from diseased and six from healthy salmon eggs (Table 1). Quantitative PCR with Trichoderma-specific primers showed that Trichoderma was present in higher abundance in total DNA samples of healthy than of diseased salmon eggs (Figure 3), although some variation in results were observed between replicated PCR reactions on the same DNA samples (Supplementary Material, Figure S1). The total fungal community did not differ in abundance between healthy and diseased salmon eggs (Figure 3). Collectively, these results suggest that Trichoderma is more enriched in healthy salmon egg samples than in diseased salmon egg samples. Phylogenetic analyses based on ITS sequences showed that all nine Trichoderma isolates belonged to the Trichoderma section [64] and no apparent separation was observed between isolates from diseased or healthy salmon eggs based on ITS sequences (Figure 5). However, phylogeny based on sequences of the translation elongation factor 1 alpha (tef1) clearly separated the Trichoderma isolates from diseased and healthy salmon eggs (Figure 6). Our nine Trichoderma isolates and the Trichoderma viride reference strains [65,66] formed three clades of Trichoderma viride. These results suggest that next to a quantitative difference also a qualitative difference in Trichoderma populations from diseased and healthy salmon eggs.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of ITS rRNA sequences of nine Trichoderma isolates and reference strains. The phylogenetic analyses were conducted in Mega 5 using the Tamura 3-parameter method [70] to compute evolutionary distances. The bootstrap values indicated at the nodes are based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branch values lower than 50% are hidden. Closed and open circles indicate isolates from Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) or healthy samples, respectively. Red, blue and black colors indicate strains from terrestrial/plant, aquatic and unknown sources of isolation, respectively. The scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.01 nucleotide substitution per sequence position. Outer labels describe section names based on the list of species in ISTH website [64] and only sections contained at least five strains are indicated. 104 ITS sequences of good quality and at least 550 bp of reference strains of Trichoderma were downloaded from GenBank; their corresponding strain names are preceded by the accession numbers. Strain names followed by “(T)” indicate type strains.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of tef1 sequences of nine Trichoderma viride isolates and reference strains. The phylogenetic analyses were conducted in Mega 5 using the Tamura-Nei method [71] to compute evolutionary distances. The bootstrap values indicated at the nodes are based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branch values lower than 50% are hidden. Closed and open circles indicate isolates from Saprolegnia-infected (diseased) or healthy samples, respectively. Red, blue and black colors indicate strains from terrestrial/plant, aquatic and unknown sources of isolation, respectively. The scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.01 nucleotide substitution per sequence position. 11 sequences of good quality and at least 1200 bp of reference strains of Trichoderma were downloaded from GenBank; their strain names are preceded by the accession numbers. Strain name followed by “(T)” indicates type strain.

In terms of extracellular activity, we observed that the culture filtrate of only one Trichoderma isolate showed inhibition of hyphal growth of S. diclina (Table 1). Dual culture assays did not show inhibition of hyphal growth of S. diclina by any of the Trichoderma isolates tested (Table 1, Figure 4a). However, the hyphae of most Trichoderma isolates coiled around or produced a papilla-like structure on the hyphae of S. diclina (Table 1 and Figure 4b) [26]. The coiling and papilla-like structures suggest attachment of Trichoderma hyphae to S. diclina hyphae. Coiling is required for mycoparasitism but not all coiling leads to mycoparasitism [26,54,55,67]. The formation of papilla-like structures in the interaction with S. diclina could indicate the start of mycoparasitic invasion by Trichoderma; these structures have been shown to induce hyphal breakdown of various hosts [26,54,55,68,69].

Even though Trichoderma species are commonly considered beneficial fungi, some Trichoderma strains, including T. harzianum, Trichoderma koningii, Trichoderma longibrachiatum, Trichoderma pseudokoningii and Trichoderma viride, maybe pathogenic to human [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Some marine Trichoderma were associated to contaminated mussels and some were even toxic to aquatic animals, such as Artemia larvae [25,88]. Therefore, evaluations of the adverse effects of our Trichoderma isolates on the environment and humans are needed.

Previous work by Abdelhamid et al. (2007) indicated that T. viride can enhance body weight and reduce mortality of Nile tilapia treated with Saprolegnia sp. [31]. Our isolates belong to the T. viride clade and are, to our knowledge, the first characterized Trichoderma from salmon eggs. Collectively, our results pointed to both quantitative and qualitative differences in Trichoderma population between diseased and healthy salmon eggs. These analyses suggest a potential role of Trichoderma species in the protection of salmon eggs from S. diclina. Hence, our Trichoderma isolates and/or their metabolites, especially isolate 764F1 and its bioactive compounds, may have the potential to be applied in aquaculture. To this end, in vivo experiments should be conducted to determine the beneficial effects of our Trichoderma isolates in controlling Saprolegniosis and other aquaculture diseases.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of Microdochium and Trichoderma Isolates

Fungal isolation from salmon eggs was described previously by Liu et al. [18]. DNA isolation, internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rRNA sequencing and phylogenetic analyses of fungal isolates were conducted as described by Liu et al. [18]. For Trichoderma isolates, additional phylogenetic analysis was conducted with translation elongation factor 1 alpha (tef1) sequences. The tef1 gene was amplified by primer set EF1-728F [89] and TEF1LLErev [90]. The evolutionary distances of the phylogenetic trees were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter method [48] for Microdochium ITS sequences, Tamura 3-parameter method [70] for Trichoderma ITS sequences and Tamura-Nei method [71] for tef1 sequences.

3.2. Culture Filtrate Activity of Microdochium and Trichoderma Isolates

One agar plug of each Microdochium and Trichoderma isolate was pregrown in 6 mL 1/5th strength potato dextrose broth (1/5PDB, Difco™, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for one week at 20–25 °C. Each culture was lyophilized, the pellet dissolved in 6 mL fresh 1/5PDB and filter-sterilized through a 0.2 μm filter (Whatman™, Freiburg, Germany). 1 mL culture filtrate solution was added into a well of 24 well suspension culture plate (Greiner bio-one, Cellstar®, Frickenhausen, Germany) and one agar plug of Saprolegnia diclina 1152F4 was added into each well. After incubation at 14–15 °C for four days the effect of the culture filtrates on hyphal growth of S. diclina was determined.

3.3. Dual Culture Assay

One agar plug of each of the Microdochium or Trichoderma isolates and one agar plug of S. diclina were placed at two opposite sides of 1/5th strength potato dextrose agar (1/5PDA). After incubation for 6 days at 20–25 °C, inhibition of hyphal growth of S. diclina was determined and plates were stored for one to two months at 4 °C until microscopic analyses were performed. Hyphal interactions were observed under a Nikon 90i epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments Europe BV, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with brightfield settings and accomplished with Nikon NIS-elements.

3.4. Quantification of Total Fungi, Microdochium and Trichoderma in Salmon Egg Incubation Water

DNA extraction from salmon egg samples and storage was described in Liu et al. [18]. All DNA samples were thawed on ice and normalized to 5 ± 1 ng·μL−1. To quantify total fungi in the water samples, ITS rRNA genes were amplified with ITS4 [91] and ITS9 [92] primers in 12 μL volumes, each consisted of 5 μL of DNA template, 5.8 μL BIOLINE 2x SensiFAST SYBR No-ROX mix, 0.1 μL ITS4 primer (10 mM), 0.1 μL ITS9 primer (10 mM) and 1 μL BSA (0.1 mg·mL−1). The quantitative PCR program consisted of 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 30 s, 82 °C for 15 s. To quantify Microdochium lycopodinum/Microdochium phragmitis in the water samples, MPF (5′-AAGGTACCCGAAAGGGTGCTGG-3′) and MPR (5′-GAATTACTGCGCTCAGAGTACGT-3′) primers were designed and firstly the accuracy was verified by PCR using the genomic DNA isolated from M. phragmitis CBS 285.71 and Microdochium nivale var. nivale CBS 110.94 as template (Supplementary Material, Figure S2). The quantitative PCR program consisted of 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 30 s, 82 °C for 15 s. To quantify Trichoderma in the water samples, Trichoderma specific genes were amplified with ITS1TrF and ITS4TrR primers [93] and QIAGEN Rotor-Gene® SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix 2x was used. The quantitative PCR program consisted of 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, 45 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 51 °C for 10 s, 72 °C for 20 s, 82 °C for 10 s. Genomic DNA of Trichoderma isolates 1152F1 and 762F1b, and Microdochium isolates 736F1a and 749F1 was isolated with PowerSoil® DNA isolation kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Dilution series of DNA of each strain was prepared at 5, 5 × 10−1, 5 × 10−2, 5 × 10−3, 5 × 10−4, 5 × 10−5, 5 × 10−6, 5 × 10−7 ng·μL−1 and used as standards (Supplementary Material, Figure S3).

3.5. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

All DNA sequences have been deposited in GenBank. The accession numbers for the internal transcribed spacer sequences of Trichoderma, Microdochium and Mortierella are KU202214-22, KU202223-31 and KU202232-33, respectively. The accession numbers for the sequences of translation elongation factor 1 alpha of Trichoderma isolates are KU202234-42.

4. Conclusions

Aquaculture has become one of the fastest developing animal food sectors [94], partly due to regulations to protect wild fish populations from overfishing and the increased demand for fish products [1]. To support this increase in food demand, aquaculture production is gradually intensifying, but effective and sustainable strategies are needed to suppress emerging diseases including Saprolegniosis. Very few studies have demonstrated the beneficial activity of fungi against aquatic pathogens [31,95]. Our study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish correlations between the frequency/occurrence of indigenous fungal communities (Trichoderma and Microdochium species) and the health status of salmon eggs in a commercial hatchery. Our study is also the first to assess the diversity among Trichoderma and Microdochium isolates from aquaculture samples. The traditional plate assays provided informative results showing the potential antagonistic activity of our Trichoderma isolates obtained from salmon eggs against the pathogen Saprolegnia diclina. These results demonstrated the basic characters of our Trichoderma isolates, which provide a good starting point for future analyses on the molecular basis of Trichoderma-Saprolegnia interactions. Further in vitro and in vivo tests are needed to confirm their beneficial protective activity in situ. The role of Trichoderma in Saprolegnia disease suppression is especially interesting, since Trichoderma was shown to be more abundant in healthy salmon eggs than in diseased ones and showed a mycoparasitic interaction with Saprolegnia. Our study provides a framework to isolate and monitor putative protective fungi in Saprolegnia control and possibly other emerging diseases in aquaculture.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by SAPRO (Sustainable Approaches to Reduce Oomycete (Saprolegnia) Infections in Aquaculture, 238550), a Marie Curie Initial Training Network funded by the European Commission under Framework Program 7; ParaFishControl (Advanced Tools and Research Strategies for Parasite Control in European farmed fish, 634429), a Research and Innovation action funded by the European Commission under HORIZON 2020. The funds for covering the costs to publish in open access are received from ParaFishControl. We thank Klaas Bouwmeester (Wageningen University) for his help with microscopic work. We thank Emilia Hannula, Rosalinde M. Keijzer, Saskia Gerards, Agata Pijl (NIOO-KNAW) and Johnny Soares (Agronomic Institute—IAC, Brazil) for their advices in quantitative PCR. This manuscript is publication number 6010 of Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW).

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/17/1/140/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Yiying Liu, Christin Zachow, Irene de Bruijn and Jos M. Raaijmakers. Performed the experiments: Yiying Liu. Analyzed the data: Yiying Liu, Christin Zachow, Irene de Bruijn. Created figures: Yiying Liu, Irene de Bruijn. Wrote the paper: Yiying Liu, Irene de Bruijn, Jos M. Raaijmakers. Contributed to phylogenetic analyses, microscopic observation and quantitative PCR design: Christin Zachow. Designed M. lycopodinum/M. phragmitis specific primers: Yiying Liu, Irene de Bruijn. Contributed to review of the manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bruno D., van West P., Beakes G. Saprolegnia and other oomycetes. In: Woo P., Bruno D., editors. Fish Diseases and Disorders, Viral, Bacterial and Fungal Infections. Volume 3. CABI; Wallingford, UK: 2011. pp. 669–720. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van West P. Saprolegnia parasitica, an oomycete pathogen with a fishy appetite: New challenges for an old problem. Mycologist. 2006;20:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mycol.2006.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatai K., Hoshiai G. Mass mortality in cultured coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) due to Saprolegnia parasitica coker. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:532–536. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatai K., Hoshiai G.-I. Characteristics of two Saprolegnia species isolated from coho salmon with Saprolegniosis. J. Aquat. Anim. Health. 1993;5:115–118. doi: 10.1577/1548-8667(1993)005<0115:COTSSI>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van den Berg A.H., McLaggan D., Diéguez-Uribeondo J., van West P. The impact of the water moulds Saprolegnia diclina and Saprolegnia parasitica on natural ecosystems and the aquaculture industry. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2013;27:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fbr.2013.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irianto A., Austin B. Probiotics in aquaculture. J. Fish Dis. 2002;25:633–642. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2002.00422.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang C.I., Liu W.Y. An evaluation of two probiotic bacterial strains, Enterococcus faecium SF68 and Bacillus toyoi, for reducing edwardsiellosis in cultured European eel, Anguilla anguilla L. J. Fish Dis. 2002;25:311–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2002.00365.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taoka Y., Maeda H., Jo J.-Y., Jeon M.-J., Bai S.C., Lee W.-J., Yuge K., Koshio S. Growth, stress tolerance and non-specific immune response of Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus to probiotics in a closed recirculating system. Fish. Sci. 2006;72:310–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-2906.2006.01152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatesoupe F.-J. Updating the importance of lactic acid bacteria in fish farming: Natural occurrence and probiotic treatments. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;14:107–114. doi: 10.1159/000106089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lara-Flores M., Olvera-Novoa M.A., Guzmán-Méndez B.E., López-Madrid W. Use of the bacteria Streptococcus faecium and Lactobacillus acidophilus, and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as growth promoters in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Aquaculture. 2003;216:193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00277-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatai K., Willoughby L.G. Saprolegnia parasitica from rainbow trout inhibited by the bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens. Bull. Eur. Ass. Fish Pathol. 1988;8:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bly J.E., Quiniou S.M.A., Lawson L.A., Clem L.W. Inhibition of Saprolegnia pathogenic for fish by Pseudomonas fluorescens. J. Fish Dis. 1997;20:35–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.1997.d01-104.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussein M.M.A., Hatai K. In vitro inhibition of Saprolegnia by bacteria isolated from lesions of salmonids with saprolegniasis. Fish Pathol. 2001;36:73–78. doi: 10.3147/jsfp.36.73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lategan M.J., Gibson L.F. Antagonistic activity of Aeromonas media strain A199 against Saprolegnia sp., an opportunistic pathogen of the eel, Anguilla australis Richardson. J. Fish Dis. 2003;26:147–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2003.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lategan M.J., Torpy F.R., Gibson L.F. Biocontrol of saprolegniosis in silver perch Bidyanus bidyanus (Mitchell) by Aeromonas media strain A199. Aquaculture. 2004;235:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2003.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lategan M.J., Torpy F.R., Gibson L.F. Control of saprolegniosis in the eel Anguilla australis Richardson, by Aeromonas media strain A199. Aquaculture. 2004;240:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carbajal-González M.T., Fregeneda-Grandes J.M., Suárez-Ramos S., Rodríguez-Cadenas F., Aller-Gancedo J.M. Bacterial skin flora variation and in vitro inhibitory activity against Saprolegnia parasitica in brown and rainbow trout. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2011;96:125–135. doi: 10.3354/dao02391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y., de Bruijn I., Jack A.L.H., Drynan K., van den Berg A.H., Thoen E., Sandoval-Sierra V., Skaar I., van West P., Dieguez-Uribeondo J., et al. Deciphering microbial landscapes of fish eggs to mitigate emerging diseases. ISME J. 2014;8:2002–2014. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell W.A. A new species of Coniothyrium parasitic on sclerotia. Mycologia. 1947;39:190–195. doi: 10.2307/3755006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandys-Winsch C., Whipps J.M., Gerlagh M., Kruse M. World distribution of the sclerotial mycoparasite Coniothyrium minitans. Mycol. Res. 1993;97:1175–1178. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)81280-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vargas Gil S., Pastor S., March G.J. Quantitative isolation of biocontrol agents Trichoderma spp., Gliocladium spp. and actinomycetes from soil with culture media. Microbiol. Res. 2009;164:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasa P., Modugapalem H., Battini K. Isolation, screening, and molecular characterization of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria isolates of Azotobacter and Trichoderma and their beneficial activities. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015;6:360–363. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.160006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez L.L.M.A., Aganon C.P., Juico P.P. Isolation of Trichoderma species from carabao manure and evaluation of its beneficial uses. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2014;3:190–199. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulaw T.B., Druzhinina I.S., Kubicek C.P., Atanasova L. Novel endophytic Trichoderma spp. isolated from healthy Coffea arabica roots are capable of controlling coffee Tracheomycosis. Diversity. 2013;5:750–766. doi: 10.3390/d5040750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallenave-Namont C., Pouchus Y.F., Robiou du Pont T., Lassus P., Verbist J.F. Toxigenic saprophytic fungi in marine shellfish farming areas. Mycopathologia. 2000;149:21–25. doi: 10.1023/A:1007259810190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Druzhinina I.S., Seidl-Seiboth V., Herrera-Estrella A., Horwitz B.A., Kenerley C.M., Monte E., Mukherjee P.K., Zeilinger S., Grigoriev I.V., Kubicek C.P. Trichoderma: The genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolken W.A.M., Tramper J., van der Werf M.J. What can spores do for us? Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:338–345. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Vrije T., Antoine N., Buitelaar R.M., Bruckner S., Dissevelt M., Durand A., Gerlagh M., Jones E.E., Luth P., Oostra J., et al. The fungal biocontrol agent Coniothyrium minitans: Production by solid-state fermentation, application and marketing. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001;56:58–68. doi: 10.1007/s002530100678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kmet V., Flint H.J., Wallace R.J. Probiotics and manipulation of rumen development and function. Arch. Anim. Nutri. 1993;44:1–10. doi: 10.1080/17450399309386053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.BioZyme, Inc. [(accessed on 4 December 2015)]. Available online: http://vitaferm.com/products/amaferm-digest-more/

- 31.Abdelhamid A.M., Shabana Y.M., Gomaa S.S.A. Aquatic Fungi and Fish Production in Egypt, II—In Vivo Studies. [(accessed on 4 December 2015)]. Available online: http://en.engormix.com/MA-aquaculture/articles/aquatic-fungi-fish-production-t460/MYC-p0.htm.

- 32.Neospark. [(accessed on 4 December 2015)]. Available online: http://www.neospark.com/hetronex-abtp.html.

- 33.Passarini M.R.Z., Santos C., Lima N., Berlinck R.G.S., Sette L.D. Filamentous fungi from the Atlantic marine sponge Dragmacidon reticulatum. Arch. Microbiol. 2013;195:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s00203-012-0854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dörr A.J.M., Elia A.C., Rodolfi M., Garzoli L., Picco A.M., D’Amen M., Scalici M. A model of co-occurrence: Segregation and aggregation patterns in the mycoflora of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii in Lake Trasimeno (central Italy) J. Limnol. 2012;71:135–143. doi: 10.4081/jlimnol.2012.e14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alford D.V. Pest and Disease Management Handbook. WILEY; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horst R.K. Westcott’s Plant Disease Handbook. Springer; Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook R.J. Fusarium diseases of wheat and other small grains in North America. In: Nelson P.E., Toussoun T.A., Cook R.J., editors. Fusarium Diseases, Biology, and Taxonomy. Pennsylvania State University Press; University Park, PA, USA: 1981. pp. 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson D.R., Rezanoor H.N., Parry D.W., Nicholson P. Evidence for differential host preference in Microdochium nivale var. majus and Microdochium nivale var. nivale. Plant Pathol. 2000;49:261–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.2000.00453.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong S.K., Kim W.G., Choi H.W., Lee S.Y. Identification of Microdochium bolleyi associated with basal rot of creeping bent grass in Korea. Mycobiology. 2008;36:77–80. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2008.36.2.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto N. Snow molds: A group of fungi that prevail under snow. Microbes Environ. 2009;24:14–20. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME09101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rapacz M., Ergon A., Hoglind M., Jorgensen M., Jurczyk B., Ostrem L., Rognli O.A., Tronsmo A.M. Overwintering of herbaceous plants in a changing climate. Still more questions than answers. Plant Sci. 2014;225:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X., Nicholson P. Community ecology of fungal pathogens causing wheat head blight. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009;47:83–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daamen R.A., Langerak C.J., Stol W. Surveys of cereal diseases and pests in the netherlands. 3. Monographella nivalis and Fusarium spp. in winter-wheat fields and seed lots. Neth. J. Plant Pathol. 1991;97:105–114. doi: 10.1007/BF01974274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Hashimi M.H., Perry D.A. Fungal antagonists of Gerlachia nivalis. J. Phytopathol. 1986;116:106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1986.tb00901.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ernst M., Neubert K., Mendgen K.W., Wirsel S.G.R. Niche differentiation of two sympatric species of Microdochium colonizing the roots of common reed. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaklitsch W., Voglmayr H. Phylogenetic relationships of five genera of Xylariales and Rosasphaeria gen. nov. (Hypocreales) Fungal Divers. 2012;52:75–98. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0104-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg G., Zachow C., Lottmann J., Gotz M., Costa R., Smalla K. Impact of plant species and site on rhizosphere-associated fungi antagonistic to Verticillium dahliae kleb. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4203–4213. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4203-4213.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhosale S.H., Patil K.B., Parameswaran P.S., Naik C.G., Jagtap T.G. Active pharmaceutical ingredient (api) from an estuarine fungus, Microdochium nivale (Fr.) J. Environ. Biol. 2011;32:653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santiago I.F., Alves T.M.A., Rabello A., Sales Junior P.A., Romanha A.J., Zani C.L., Rosa C.A., Rosa L.H. Leishmanicidal and antitumoral activities of endophytic fungi associated with the Antarctic angiosperms Deschampsia antarctica Desv. and Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. Extremophiles. 2012;16:95–103. doi: 10.1007/s00792-011-0409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schuster A., Schmoll M. Biology and biotechnology of Trichoderma. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;87:787–799. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2632-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verma M., Brar S.K., Tyagi R.D., Surampalli R.Y., Valero J.R. Antagonistic fungi, Trichoderma spp.: Panoply of biological control. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007;37:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2007.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schirmbӧck M., Lorito M., Wang Y.L., Hayes C.K., Arisanatac I., Scala F., Harman G.E., Kubicek C.P. Parallel formation and synergism of hydrolytic enzymes and peptaibol antibiotics, molecular mechanisms involved in the antagonistic action of Trichoderma harzianum against phytopathogenic fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994;60:4364–4370. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4364-4370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harman G.E. Multifunctional fungal plant symbionts: New tools to enhance plant growth and productivity. New Phytol. 2011;189:647–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harman G.E., Howell C.R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Lorito M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hageskal G., Vrålstad T., Knutsen A.K., Skaar I.D.A. Exploring the species diversity of Trichoderma in Norwegian drinking water systems by DNA barcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008;8:1178–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gal-Hemed I., Atanasova L., Komon-Zelazowska M., Druzhinina I.S., Viterbo A., Yarden O. Marine isolates of Trichoderma spp. As potential halotolerant agents of biological control for arid-zone agriculture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:5100–5109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00541-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu B., Oesker V., Wiese J., Schmaljohann R., Imhoff J.F. Two new antibiotic pyridones produced by a marine fungus, Trichoderma sp. strain MF106. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:1208–1219. doi: 10.3390/md12031208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou K., Zhang X., Zhang F., Li Z. Phylogenetically diverse cultivable fungal community and polyketide synthase (PKS), non-ribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) genes associated with the South China Sea sponges. Microb. Ecol. 2011;62:644–654. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9859-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miao L., Qian P.Y. Antagonistic antimicrobial activity of marine fungi and bacteria isolated from marine biofilm and seawaters of Hong Kong. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2005;38:231–238. doi: 10.3354/ame038231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamazaki H., Saito R., Takahashi O., Kirikoshi R., Toraiwa K., Iwasaki K., Izumikawa Y., Nakayama W., Namikoshi M. Trichoketides A and B, two new protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors from the marine-derived fungus Trichoderma sp. J. Antibiot. 2015;68:628–632. doi: 10.1038/ja.2015.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamada T., Umebayashi Y., Kawashima M., Sugiura Y., Kikuchi T., Tanaka R. Determination of the chemical structures of Tandyukisins B–D, isolated from a marine sponge-derived fungus. Mar. Drugs. 2015;13:3231–3240. doi: 10.3390/md13053231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Citarasu T. Natural antimicrobial compounds for use in aquaculture. In: Austin B., editor. Infectious Disease in Aquaculture. Woodhead Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2012. pp. 419–456. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Druzhinina I., Kopchinskiy A. International Subcommission on Trichoderma and Hypocrea Taxonomy. [(accessed on 4 December 2015)]. Available online: http://isth.info/

- 65.Jaklitsch W.M., Samuels G.J., Dodd S.L., Lu B.S., Druzhinina I.S. Hypocrea rufa/Trichoderma viride: A reassessment, and description of five closely related species with and without warted conidia. Stud. Mycol. 2006;56:135–177. doi: 10.3114/sim.2006.56.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jaklitsch W.M. European species of Hypocrea part II: Species with hyaline ascospores. Fungal Divers. 2011;48:1–250. doi: 10.1007/s13225-011-0088-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu Z.X., Tombolini R., Woo S., Zeilinger S., Lorito M., Jansson J.K. In vivo study of Trichoderma-pathogen-plant interactions, using constitutive and inducible green fluorescent protein reporter systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:3073–3081. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.3073-3081.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chacón M.R., Rodríguez-Galán O., Benítez T., Sousa S., Rey M., Llobell A., Delgado-Jarana J. Microscopic and transcriptome analyses of early colonization of tomato roots by Trichoderma harzianum. Int. Microbiol. 2007;10:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rocha-Ramírez V., Omero C., Chet I., Horwitz B.A., Herrera-Estrella A. Trichoderma atroviride G-protein alpha-subunit gene tga1 is involved in mycoparasitic coiling and conidiation. Eukaryot. Cell. 2002;1:594–605. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.4.594-605.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G + C-content biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992;9:678–687. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tamura K., Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Miguel D., Gomez P., Gonzalez R., Garcia-Suarez J., Cuadros J.A., Banas M.H., Romanyk J., Burgaleta C. Nonfatal pulmonary Trichoderma viride infection in an adult patient with acute myeloid leukemia: Report of one case and review of the literature. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2005;53:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loeppky C.B., Sprouse R.F., Carlson J.V., Everett E.D. Trichoderma viride peritonitis. South. Med. J. 1983;76:798–799. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198306000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Escudero Gil M.R., Pino C.E., Munoz R. Pulmonary mycoma cause by Trichoderma viride. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 1976;67:673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacobs F., Byl B., Bourgeois N., Coremans-Pelseneer J., Florquin S., Depre G., van de Stadt J., Adler M., Gelin M., Thys J.P. Trichoderma viride infection in a liver transplant recipient. Mycoses. 1992;35:301–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1992.tb00880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rota S., Marchesi D., Farina C., de Bievre C. Trichoderma pseudokoningii peritonitis in automated peritoneal dialysis patient successfully treated by early catheter removal. Perit. Dial. Int. 2000;20:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guiserix J., Ramdane M., Finielz P., Michault A., Rajaonarivelo P. Trichoderma harzianum peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis. Nephron. 1996;74:473–474. doi: 10.1159/000189374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Campos-Herrero M., Bordes A., Perera A., Ruiz M., Fernández A. Trichoderma koningii peritonitis in a patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 1996;18:150–152. doi: 10.1016/0196-4399(96)83918-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tanis B.C., van der Pijl H., van Ogtrop M.L., Kibbelaar R.E., Chang P.C. Fatal fungal peritonitis by Trichoderma longibrachiatum complicating peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1995;10:114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Richter S., Cormican M.G., Pfaller M.A., Lee C.K., Gingrich R., Rinaldi M.G., Sutton D.A. Fatal disseminated Trichoderma longibrachiatum infection in an adult bone marrow transplant patient: Species identification and review of the literature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:1154–1160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1154-1160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gautheret A., Dromer F., Bourhis J.H., Andremont A. Trichoderma pseudokoningii as a cause of fatal infection in a bone marrow transplant recipient. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995;20:1063–1064. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chouaki T., Lavarde V., Lachaud L., Raccurt C.P., Hennequin C. Invasive infections due to Trichoderma species: Report of 2 cases, findings of in vitro susceptibility testing, and review of the literature. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35:1360–1367. doi: 10.1086/344270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guarro J., Antolín-Ayala M.I., Gené J., Gutiérrez-Calzada J., Nieves-Díez C., Ortoneda M. Fatal case of Trichoderma harzianum infection in a renal transplant recipient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:3751–3755. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3751-3755.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Seguin P., Degeilh B., Grulois I., Gacouin A., Maugendre S., Dufour T., Dupont B., Camus C. Successful treatment of a brain abscess due to Trichoderma longibrachiatum after surgical resection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1995;14:445–448. doi: 10.1007/BF02114902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Furukawa H., Kusne S., Sutton D.A., Manez R., Carrau R., Nichols L., Abu-Elmagd K., Skedros D., Todo S., Rinaldi M.G. Acute invasive sinusitis due to Trichoderma longibrachiatum in a liver and small bowel transplant recipient. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998;26:487–489. doi: 10.1086/516317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Munoz F.M., Demmler G.J., Travis W.R., Ogden A.K., Rossmann S.N., Rinaldi M.G. Trichoderma longibrachiatum infection in a pediatric patient with aplastic anemia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35:499–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.499-503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Myoken Y., Sugata T., Fujita Y., Asaoku H., Fujihara M., Mikami Y. Fatal necrotizing stomatitis due to Trichoderma longibrachiatum in a neutropenic patient with malignant lymphoma: A case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002;31:688–691. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marrouchi R., Benoit E., le Caer J.-P., Belayouni N., Belghith H., Molgó J., Kharrat R. Toxic C17-sphinganine analogue mycotoxin, contaminating Tunisian mussels, causes flaccid paralysis in rodents. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:4724. doi: 10.3390/md11124724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cortinas M.-N., Crous P.W., Wingfield B.D., Wingfield M.J. Multi-gene phylogenies and phenotypic characters distinguish two species within the Colletogloeopsis zuluensis complex associated with Eucalyptus stem cankers. Stud. Mycol. 2006;55:133–146. doi: 10.3114/sim.55.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nagy V., Seidl V., Szakacs G., Komofl-Zelazowska M., Kubicek C.P., Druzhinina I.S. Application of DNA bar codes for screening of industrially important fungi: The haplotype of Trichoderma harzianum sensu stricto indicates superior chitinase formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:7048–7058. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00995-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ihrmark K., Bödeker I.T.M., Cruz-Martinez K., Friberg H., Kubartova A., Schenck J., Strid Y., Stenlid J., Brandström-Durling M., Clemmenssen K.E., et al. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region—Evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012;82:666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meincke R., Weinert N., Radl V., Schloter M., Smalla K., Berg G. Development of a molecular approach to describe the composition of Trichoderma communities. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2010;80:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Food and Agriculture Organization . The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2014. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Rome, Italy: 2014. p. 223. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Woodhams D.C., Brandt H., Baumgartner S., Kielgast J., Küpfer E., Tobler U., Davis L.R., Schmidt B.R., Bel C., Hodel S., et al. Interacting symbionts and immunity in the amphibian skin mucosome predict disease risk and probiotic effectiveness. PLoS ONE. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.