Abstract

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli is an important etiological agent of avian colibacillosis, which manifests as respiratory, hematogenous, meningitic, and enteric infections in poultry. It is also a potential zoonotic threat to human health. The diverse genomes of APEC strains largely hinder disease prevention and control measures. In the current study, pyrosequencing was used to analyze and characterize APEC strain ACN001 (= CCTCC 2015182T = DSMZ 29979T), which was isolated from the liver of a diseased chicken in China in 2010. Strain ACN001 belongs to extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli phylogenetic group B1, and was highly virulent in chicken and mouse models. Whole genome analysis showed that it consists of six different plasmids along with a circular chromosome of 4,936,576 bp, comprising 4,794 protein-coding genes, 108 RNA genes, and 51 pseudogenes, with an average G + C content of 50.56 %. As well as 237 coding sequences, we identified 39 insertion sequences, 12 predicated genomic islands, 8 prophage-related sequences, and 2 clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats regions on the chromosome, suggesting the possible occurrence of horizontal gene transfer in this strain. In addition, most of the virulence and antibiotic resistance genes were located on the plasmids, which would assist in the distribution of pathogenicity and multidrug resistance elements among E. coli populations. Together, the information provided here on APEC isolate ACN001 will assist in future study of APEC strains, and aid in the development of control measures.

Keywords: APEC, Colibacillosis, Genome sequencing, Chromosome, Plasmid

Introduction

The group known as extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC), including uropathogenic E. coli, neonatal-meningitis E. coli, and avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC), encompasses E. coli strains that cause severe extraintestinal systemic infections such as septicemia, meningitis, and pyelonephritis in both humans and animals. In the veterinary field, APEC mainly causes avian colisepticemia, a widespread infectious disease that leads to significant economic losses in the poultry industry [1, 2]. It has also been widely reported to represent a zoonotic risk, with the potential for spread between animals and humans [3]. However, an incomplete understanding of the genetic features, as well as the genome diversity and frequent occurrence of horizontal gene transfer in APEC, has made it very difficult to carry out pathogenesis studies aimed at preventing APEC infections [4]. Therefore, it is important to explore any useful features within APEC genomes.

Here, we report the full genome sequence and preliminary functional annotation of virulent APEC strain ACN001 (= CCTCC 2015182T = DSMZ 29979T), which was isolated from a chicken suffering from avian colibacillosis. The study aimed to characterize the genomic features of strain ACN001 to provide information that will drive further study of APEC to better control its spread.

Organism information

Classification and features

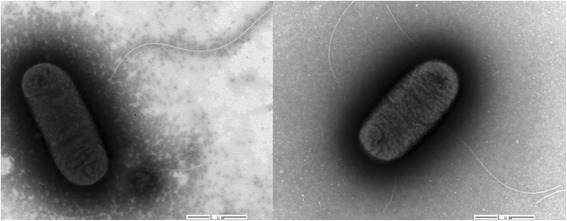

APEC is a Gram-negative, aerobic and facultatively anaerobic, non-spore forming, short to medium rod-shaped bacterium, which belongs to the Escherichia genus of the family Enterobacteriaceae (Table 1). It is an etiologic agent of avian colibacillosis, which mainly causes systemic extraintestinal diseases in poultry, including respiratory, hematogenous, meningitic, and enteric infections [5]. Based on previous chicken and mouse models infection studies, APEC strain ACN001 is a highly virulent field isolate, with a length of 1–2 μm and a diameter of 0.5–0.8 μm. It is a mesophile that can grow at temperatures of 10–45 °C, with optimum growth from 37–42 °C (Table 1). It is motile by the means of peritrichous flagella (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Classification and general features of APEC strain ACN001

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [24] | |

| Phylum Proteobacteria | TAS [25] | ||

| Class Gammaproteobacteria | TAS [26, 27] | ||

| Order ‘Enterobacteriales’ | TAS [26, 27] | ||

| Family Enterobacteriaceae | TAS [28] | ||

| Genus Escherichia | TAS [29, 30] | ||

| Species Escherichia coli | TAS [29, 30] | ||

| Gram stain | Negative | TAS [31] | |

| Cell shape | Rod | TAS [31] | |

| Motility | Motile | TAS [31] | |

| Sporulation | None-sporeforming | TAS [31] | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | TAS [31] | |

| Optimum temperature | 37 °C | TAS [31] | |

| pH range; Optimum | 5.5–8.0; 7.0 | TAS [31] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Host-associated | TAS [1, 32] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity range | Not reported | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobe and facultative anaerobe | TAS [31, 33] |

| Carbon source | Carbohdrates, salicin, sorbitol, mannitol, indole, peptides | TAS [34] | |

| Energy metabolism | Chemo-organotrophic | TAS [33] | |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Parasitism | TAS [1, 32] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Pathogenic | TAS [1, 32] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | China | NAS |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | 2010 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported |

aEvidence codes - TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence); IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay. These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [35]

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron micrograph of APEC strain ACN001 (= CCTCC 2015182T = DSMZ 29979T). Strain ACN001 is a short to medium rod-shaped bacterium with a length of 1–2 μm and a diameter of 0.5–0.8 μm. It moves via peritrichous flagella. The magnification rate is 20,000×. The scale bar indicates 1 μm

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of ACN001 was compared with those of other E. coli strains available from the GenBank database using BLAST with default settings [6]. The APEC strain ACN001 16S rRNA gene shared an average nucleotide identity of 99.61 % with the corresponding regions of published strains, including E. coli UMNK88 (GenBank accession no. CP002729.1, 100 %), E. coli 12009 (AP010958.1, 100 %), E. coli BL21(DE3) (CP001509.3, 100 %), E. coliATCC 8739 (CP000946.1, 100 %), E. coli APEC O78 (CP004009.1, 100 %), E. coli IAI39 (CU928164.2, 99 %), E. coli UMN026 (CU928163.2, 99 %), E. coli K12substr. MG1655 (U00096.3, 99 %), E. coli K12substr. DH10B (CP000948.1, 99 %), E. coli K12substr. W3110 (AP009048.1, 99 %), E. coli APEC O1 (CP000468.1, 99 %), E. coli CFT073 (AE014075.1, 99 %), and E. coli UTI89 (CP000243.1, 99 %).

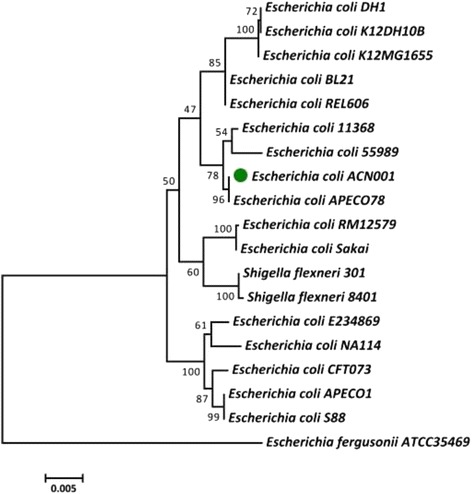

ExPEC strains can be divided into different E. coli Collection Reference phylogroups (A, B1, B2, D and E) according to the sequences of housekeeping genes (e.g., adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) [7, 8]. We constructed a phylogenetic tree based on the aligned gene sequences using a maximum likelihood approach and MEGA (version 5), with 1,000 randomly selected bootstrap replicates [7] (Fig. 2). ACN001 belonged to phylogenetic group B1, and was located on the same branch as APEC O78, another highly virulent group B1 strain [7]. Genes from the following strains were used to construct the phylogenetic tree: E. coli DH1 (GenBank accession no. NC_017625), E. coli K12 DH10B (NC_010473), E. coli K12 MG1655 (NC_000913), E. coli BL21 (NC_012947), E. coli REL606 (NC_012967), E. coli 11368 (NC_013361), E. coli 55989 (NC_011748), E. coli APEC O78 (NC_020163), E. coli RM12579 (NC_017656), E. coli Sakai (NC_002695), Shigella flexneri 301 (NC_004337), Shigella flexneri 8401 (NC_008258), E. coli E234869 (NC_011601), E. coli NA114 (NC_017644), E. coli CFT073 (NC_004431), E. coli APEC O1 (NC_008563), E. coli S88 (NC_011742). Escherichia fergusoniiATCC35469 (NC_011740) was used as an out-group.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of ACN001 relative to other strains within the Enterobacteriaceae family. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on seven housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) according to the aligned gene sequences using maximum likelihoods derived from MEGA software version 5. The scale bar represents the divergence time of different strains. Escherichia fergusonii (ATCC35469) was used as an out-group

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

APEC strain ACN001 was selected for whole genome sequencing at the Chinese National Human Genome Center in Shanghai, China, because of its high virulence and potential zoonotic risk. Sequence assembly and annotation were completed in December 2012, and the complete genome sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number CP007442. A summary of the project information and its association with “Minimum Information about a Genome Sequence” [9] are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genome sequencing project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | 454 Titanium paired-end library (800-bp insert size) |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454-GS-FLX-Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 23.58× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | GeneMark, Glimmer |

| Locus tag | J444 | |

| GenBank ID | CP007442 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | 09-July-2015 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA234088 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source Material Identifier | CCTCC 2015182 |

| Project relevance | Pathogenic bacterium, biotechnological |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

APEC strain ACN001 was cultivated on LB medium as previously described [1]. High quality genomic DNA for sequencing was extracted using a cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method, and the concentration and purity were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The complete genome of APEC strain ACN001 was sequenced using the Roche 454 GS-FLX platform (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Each library fragment had an average size of 800 bp, yielding 215,687 reads corresponding to approximately 166.3 Mb, and providing 23.58-fold coverage of the genome. The reads were assembled into 245 contigs using Newbler version 2.3 (454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT), including 195 large contigs that were > 500 bp. Sequence data from APEC strains O1 and O78, which showed a high level of similarity to the ACN001 draft sequences, was used as a reference for the finishing process. All large contigs were analyzed using Cytoscape software version 2.8.2 to determine their relative positions. Gap closure between large contigs was completed by sequencing potential neighboring contigs using an ABI 3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment in the subsequent finishing process. Possible misassemblies were corrected by sub-cloning and sequencing bridging PCR fragments. A total of 217 additional amplification reactions were performed to close all gaps and improve the quality of the sequences. The error rate of the final ACN001 genome sequence was less than 10−5.

Genome annotation

The complete ACN001 genome sequence was analysed using Glimmer 3.0 [10, 11] and GeneMark [12, 13] for gene prediction, the tRNAscan-SE tool for tRNA identification [14], and RNAmmer [15] for ribosomal RNA identification. The predicted protein-coding genes were translated into amino acid sequences and annotated using the NCBI and UniProt non-redundant sequence databases [16], the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database [17], and, subsequently, the Cluster of Orthologous Genes database [18] to identify the specific protein products and their functional categories. Additional gene analysis and miscellaneous features were predicted using TMHMM [19], SignalP [20], and the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology server databases [21]. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat elements were detected using CRT [22] and PILER-CR [23].

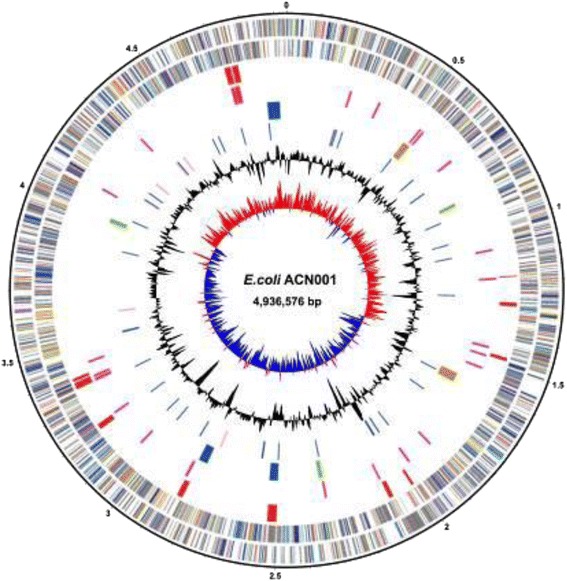

Genome properties

The complete genome of ACN001 comprises one circular chromosome of 4.9 Mb in size (4,936,576 bp, Fig. 3) and six plasmids: pACN001-A (60,043 bp), pACN001-B (168,543 bp), pACN001-C (5,784 bp), pACN001-D (6,747 bp), pACN001-E (6,822 bp) and pACN001-F (92,447 bp) (Fig. 4 and Table 3), with an average G + C content of 50.56 % (Table 4). A total of 5,253 genes were predicted in the genome, of which 4,794 coded for proteins, 108 were RNA-related, and 51 were pseudogenes. A total of 3,630 (69.11 %) of the protein-coding genes were assigned specific functions, with hypothetical functions assigned to the remaining genes. The genome properties are presented in Tables 3 and 4, and Figs. 3 and 4. The COG functional categories are listed in Table 5.

Fig. 3.

Graphical map of the APEC strain ACN001 chromosome. Circular representation of the ACN001 chromosome displaying relevant genomic features. From outside to the center: genes on the forward strand (colored by COG category), genes on the reverse strand (colored by COG category), insertion sequences (ISs), genomic islands (GIs), prophage sequences, RNAs, GC content and GC skew

Fig. 4.

Graphical map of the large plasmids in APEC strain ACN001. Circular representation of ACN001 plasmids pACN001-A, B, and F displaying relevant features. From outside to the center: genes on the forward strand (colored by COG category), genes on the reverse strand (colored by COG category), GC content, GC skew. Order and size from left to right: pACN001-A, 60,043 bp; pACN001-B, 168,543 bp; pACN001-F, 92,447 bp

Table 3.

Summary of ACN001 genome: one chromosome and six plasmids

| Label | Size (Mb) | Topology | INSDC identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 4.9 | Circular | GenBank CP007442 |

| Plasmid pACN001-A | 0.06 | Circular | GenBank KC853434 |

| Plasmid pACN001-B | 0.17 | Circular | GenBank KC853435 |

| Plasmid pACN001-C | 0.006 | Circular | GenBank KC853436 |

| Plasmid pACN001-D | 0.007 | Circular | GenBank KC853437 |

| Plasmid pACN001-E | 0.007 | Circular | GenBank KC853438 |

| Plasmid pACN001-F | 0.09 | Circular | GenBank KC853439 |

INSDC International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration

Table 4.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of Totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 5,276,962 | 100.00 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 4,614,690 | 87.45 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,669,115 | 50.56 |

| Total genes | 5,253 | 100.00 |

| Protein coding genes | 4,794 | 91.26 |

| RNA genes | 108 | 2.06 |

| tRNA genes | 86 | 1.64 |

| rRNA genes | 22 | 0.42 |

| Pseudo genes | 51 | 0.97 |

| Genes with function prediction | 3,630 | 69.11 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3,203 | 60.97 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 4,463 | 84.96 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 424 | 8.07 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,124 | 21.40 |

| CRISPR repeats | 2 |

aTotal based on either the size of the genome in base pairs (bp) or the total number of genes in the annotated genome

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 177 | 3.37 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 2 | 0.04 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 205 | 3.90 | Transcription |

| L | 197 | 3.75 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 0 | 0.00 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 41 | 0.78 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.00 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 56 | 1.07 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 90 | 1.71 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 187 | 3.56 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 106 | 2.02 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.00 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.00 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 48 | 0.91 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 116 | 2.21 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 256 | 4.87 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 286 | 5.44 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 318 | 6.05 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 84 | 1.60 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 128 | 2.44 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 76 | 1.45 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 188 | 3.58 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 62 | 1.18 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 309 | 5.88 | General function prediction only |

| S | 332 | 6.32 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,993 | 37.94 | Not in COGs |

Insights from the genome sequence

APEC infection causes significant economic losses to the poultry industry. An incomplete understanding of the APEC genome complexity impedes the study of pathogenesis and subsequent development of control measures. Here, complete genome sequencing and annotation of APEC virulent isolate ACN001 was carried out, which identified 4,794 protein-coding genes, accounting for 91.26 % of the total number of genes (5,253 genes). Notably, preliminary sequence analysis revealed 39 insertion sequences (ISs), 12 predicated genomic islands (GIs), 8 prophage-related sequences and 2 CRISPR elements. These elements involved 237 coding sequences on the circular chromosome, indicating possible genetic crosstalk among E. coli populations. These elements might represent the genetic differences between ACN001 and other APEC strains, and reflect the potential interactions of this strain with the environment. Further comparative approaches will be applied to help to better elucidate the interrelationship of these traits with certain phenotypes, such as adaptability and pathogenicity.

Moreover, six plasmids were found in strain ACN001, including three large plasmids (pACN001-A, B, and F) and three small plasmids (pACN001-C, D, and E). Antibiotic resistance genes and the majority of the essential virulence genes were located on the three large plasmids, while only 8, 9 and 10 protein-coding genes with unknown functional annotations were found on plasmids pACN001-C, D, and E, respectively. The location of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes on plasmids in strain ACN001 may allow the propagation of multidrug resistance and virulence factors among E. coli populations in poultry.

Conclusion

This study presents the whole genome sequence of APEC strain ACN001, a chicken-derived isolate causing typical avian colibacillosis. The genome of ACN001 consists of a circular chromosome containing 4,794 protein-coding genes and 108 RNA genes, along with six plasmids with different features. We observed 39 ISs, 12 predicated GIs, 8 prophage-related sequences and 2 CRISPR elements on the chromosome, suggesting frequent genetic crosstalk, such as horizontal gene transfer, between ACN001 and other E. coli populations. Among the six plasmids identified in this strain, three large plasmids contained multiple antibiotic resistance and virulence genes, while the three small plasmids contained genes with unknown functional annotations. These plasmid-borne pathogenicity-associated features should be closely monitored to prevent further spread amongst the diverse E. coli populations, especially APEC. The genome sequencing and annotation of virulent APEC isolate ACN001 provides valuable genetic information for future study of the pathogenesis of APEC strains, which will help in the development of prevention and control measures.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 31030065, No.31472201, No.31502062), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Program No. 2662014BQ022).

Abbreviations

- APEC

Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli

- ExPEC

Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli

Footnotes

Xiangru Wang and Liuya Wei contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WXR and WLY carried out the molecular genetic studies, the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. WB and ZRX assisted with the sequence alignment. LCY and BDR participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. WXR, CHC, and TC conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Dho-Moulin M, Fairbrother JM. Avian pathogenic Escherichia coli (APEC) Vet Res. 1998;30:299–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo TA, Johnson JR. Extraintestinal isolates of Escherichia coli: identification and prospects for vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:45–54. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JR, Gajewski A, Lesse AJ, Russo TA. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli as a cause of invasive nonurinary infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5798–5802. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5798-5802.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lercher MJ, Pál C. Integration of horizontally transferred genes into regulatory interaction networks takes many million years. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:559–567. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellata M. Human and avian extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: infections, zoonotic risks, and antibiotic resistance trends. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2013;10:916–932. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon DM, Clermont O, Tolley H, Denamur E. Assigning Escherichia coli strains to phylogenetic groups: multi-locus sequence typing versus the PCR triplex method. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2484–2496. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1136–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4636–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.23.4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delcher AL, Bratke KA, Powers EC, Salzberg SL. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:673–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borodovsky M, Mills R, Besemer J, Lomsadze A. Prokaryotic gene prediction using GeneMark and GeneMark.hmm. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2003;Chapter4:Unit4.5. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0405s01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Besemer J, Borodovsky M. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:451–454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:0955–0964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt H-H, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consortium U. The universal protein resource (UniProt) in 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:142–148. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:480–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, et al. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyrløv Bendtsen J, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bland C, Ramsey TL, Sabree F, Lowe M, Brown K, Kyrpides NC, et al. CRISPR recognition tool (CRT): a tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edgar RC. PILER-CR: fast and accurate identification of CRISPR repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms. Proposal for the domains Archaea and Bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Phylum XIV. Proteobacteria phyl nov. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Stanley JT, Garrity GM, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second edition, Volume 2 (The Proteobacteria part B The Gammaproteobacteria) New York: Springer; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrity GM, Bell JA, Lilburn T. Class III. Gammaproteobacteria class. nov. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 2, Part B. Springer: New York; 2005. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams KP, Kelly DP. Proposal for a new class within the phylum Proteobacteria, Acidithiobacillia classis nov., with the type order Acidithiobacillales, and emended description of the class Gammaproteobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:2901–2906. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.049270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brenner DJ, Family I. Enterobacteriaceae Rahn 1937, Nom. fam. cons. Opin. 15, Jud. Com. 1958, 73; Ewing, Farmer, and Brenner 1980, 674; Judicial Commission 1981, 104. In: Krieg NR, Holt JG, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 1. The Williams & Wilkins Co: Baltimore; 1984. pp. 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Escherich T. Die Darmbakterien des Säuglings und ihre Beziehungen zur Physiologie der Verdauung. Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke; 1886. pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Editorial Board (for the Judicial Commission of the International Committee on Bacteriological Nomenclature) Opinion 26: designation of neotype strains (cultures) of type species of the bacterial genera Salmonella, Shigella, Arizona, Escherichia, Citrobacter and Proteus of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1963;13:35. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Welch RA. 3.3.3 The Genus Escherichia. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E, editors. The Prokaryotes. 3. Berlin: Springer; 2005. pp. 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ewers C, Li G, Wilking H, Kieβling S, Alt K, Antáo E-M, et al. Avian pathogenic, uropathogenic, and newborn meningitis-causing Escherichia coli: How closely related are they? Int J Med Microbiol. 2007;297:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheutz F, Strockbine NA. Genus I. Escherichia Castellani and Chalmers 1919. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Second edition, Volume 2 (The Proteobacteria) New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 607–624. [Google Scholar]

- 34.List of growth media used at the DSMZ. http://www.dsmz.de/.

- 35.Ashburner M, Ball C, Blake J, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry J, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]