Abstract

Objective

To understand young women’s reasons for accepting or declining fertility preservation following cancer diagnosis to aid in the development of theory regarding decision making in this context.

Design

Qualitative descriptive.

Setting

Participants’ homes or other private location.

Participants

Twenty-seven young women (mean age = 29 years) diagnosed with cancer and eligible for fertility preservation.

Methods

Recruitment was conducted via the Internet and in fertility centers. Participants completed demographic questionnaires and in-depth semi-structured interviews. Tenets of grounded theory guided an inductive and deductive analysis.

Results

Young women’s reasons for deciding whether to undergo fertility preservation were linked to four theoretical dimensions: Cognitive Appraisals, Emotional Responses, Moral Judgments, and Decision Partners. Women who declined fertility preservation described more reasons in the Cognitive Appraisals dimension, including financial cost and human risks, than women who accepted. In the Emotional Responses dimension, most women who accepted fertility preservation reported a strong desire for biological motherhood, whereas women who declined tended to report a strong desire for surviving cancer. Three participants who declined reported reasons linked to the Moral Judgments dimension, and the majority were influenced by Decision Partners, including husbands, boyfriends, parents, and clinicians.

Conclusion

The primary reason upon which many but not all participants based decisions related to fertility preservation was whether the immediate emphasis of care should be placed on surviving cancer or securing options for future biological motherhood. Nurses and other clinicians should base education and counseling on the four theoretical dimensions to effectively support young women with cancer.

Keywords: decision making, oncofertility, preference formation, qualitative research, survivorship, theory development

Increasing survival rates after cancer treatment have expanded the focus of care to include survivorship issues and quality of life concerns (American Cancer Society, 2014). For example, fertility preservation (defined as egg, embryo, or ovarian tissue cryopreservation) for young women with cancer who are at-risk for fertility loss has gained wide acceptance, and egg and embryo cryopreservation are now considered standards in clinical practice (Loren et al., 2013; Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, 2013). Egg and embryo cryopreservation are typically performed in conjunction with ovarian stimulation prior to the onset of cancer treatment (Kasum, Beketić-Orešković, Peddi, Orešković, & Johnson, 2014; Trudgen & Ayensu-Coker, 2014). Ovarian tissue cryopreservation is an experimental option that when performed within a research protocol can be appropriate for young women who urgently need to undergo chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment (Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2014). Worldwide, the number of fertility centers offering fertility preservation to young women with cancer is expanding (Ory et al., 2014).

In the United States, the number of women who delay pregnancy and childbearing until they are in their thirties and forties is increasing (Hamilton, Martin, Osterman, & Curtin, 2014), and as a result, many young women diagnosed with cancer have neither begun nor completed childbearing. In some cases, young women diagnosed with cancer have not fully considered whether they want to have children. In such situations, there is a critical need for nurses and other clinicians to provide effective education and support for these young women. The body of research on the underlying reasons why young women accept or decline fertility preservation, such as associated financial costs incurred during treatment, is small but expanding. However, the accumulating evidence is often conflicted or confounded by extraneous factors and is typically void of the explicit theoretical underpinnings that are needed to examine the phenomena of decision making within this specific context. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to provide insight into the reasons why young women accept or decline fertility preservation following cancer diagnosis in order to contribute to theoretical knowledge in this area.

Background

Limited research is available about the complex decisions young women with cancer make about fertility preservation, as interest in fertility and pregnancy among these women did not occur until the early 1990s. During this time, reports of survival rates for young women with cancer began to show that those who experienced naturally occurring pregnancies post-cancer had the same prognosis as young women who did not experience pregnancy (Danforth, 1991). Then, in a groundbreaking study published in 2004, Partridge and colleagues found that of the 657 young women surveyed who survived breast cancer, an overwhelming majority (73%) indicated they were concerned about loss of fertility. Many women in this study who voiced concern about their fertility wanted children or more children. However, 36% of the women reported they did not want children in the future or were unsure about future childbearing because they thought a future pregnancy would increase the risk of cancer recurrence, a concern that was also expressed by other young cancer survivors (Avis, Crawford, & Manuel, 2004; Connell, Patterson, & Newman, 2006; Klock, Zhang, & Kazer, 2010). Some cancer survivors who did not want to become pregnant also expressed feelings of selfishness about having children when their own lifespans could be compromised (Connell et al., 2006), or they indicated that financial cost associated with fertility preservation was a barrier (Kim et al., 2013; Klock et al., 2010; Mersereau et al., 2013).

As more young women with cancer become aware of fertility preservation, the effect of clinical counseling (Bastings et al., 2014; Goodman, Balthazar, Kim, & Mersereau, 2012; King et al., 2008) on their decisions, including processes related to the exchange of information with clinicians, is being examined (Balthazar et al., 2012; Jukkala, Azuero, McNees, Bates, & Meneses, 2010). In a poignant example, Peddie et al. (2012) explored factors that affected decisions regarding fertility preservation for women and men. They found that women declined this option because their clinicians often stressed the urgent need for cancer treatment. We and other investigators found that young women’s decisions about fertility preservation were influenced by lack of clinician encouragement, lack of information, and low referral rates for fertility counseling (Hershberger, Finnegan, Altfeld, Lake, & Hirshfeld-Cytron, 2013; Hill et al., 2012; Mersereau et al., 2013; Peate et al., 2011; Thewes et al., 2005).

Kim and colleagues (2013) further explored the reasons why American women accepted fertility preservation, and the most reported were desire for future children and the wishes of the women’s partners. Among those women who declined fertility preservation, the top reasons were lack of desire for future children, financial costs, and length of time needed for treatment. Yet Peate and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that neither having a definite desire for more children nor being in a committed relationship predicted Australian women’s intentions to pursue fertility preservation. The various social, political, and cultural contexts that occur in the countries where these studies were completed add to the difficulty in understanding why young women chose fertility preservation.

Although findings from these studies are helpful to identify why young women choose fertility preservation, most investigators have not linked findings to theoretical constructs. Recently, scientists and scholars specializing in decision making have suggested that more explicit use of theoretical frameworks can help to understand decision-making processes and to interpret data (Bekker, 2009; Durand, Stiel, Boivin, & Elwyn, 2008; Pieterse, de Vries, Kunneman, Stiggelbout, & Feldman-Stewart, 2013). In a recent review, Hershberger and Pierce (2010) derived three main theoretical dimensions, Cognitive Appraisals, Emotional Responses, and Moral Judgments, related to the reasons young women and their partners choose to use preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). Similar to decisions regarding fertility preservation options of egg, embryo, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation, women and their partners often struggle to reach decisions about the use of PGD (Hershberger et al., 2012). In this study, we used the previously identified theoretical framework related to PGD to help understand young women’s reasons to accept or decline fertility preservation following cancer diagnosis.

Methods

Design

We used a descriptive, qualitative design (Sandelowski, 2000a, 2010) guided by grounded theory and the constant comparison approach (Charmaz, 2006). Prior to the initiation of the study, Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Michigan.

Sample Recruitment

Young women (N = 27) were recruited from two clinics (n = 7) and the Internet (n = 20). Multiple strategies were used to recruit participants, including the development of a study website and the placement of advertisements on websites such as Planet Cancer. Potential participants were informed of the study through brochures and by trained clinicians. To be eligible, young women had to meet the following inclusion criteria: English speaking, between 18 and 42 years of age, diagnosed with cancer, eligible for fertility preservation, made a decision about whether to accept or decline fertility preservation within the past 18 months, and willing and able to talk or write about their decision-making experience. The age requirement of 18–42 years correlated with the typical age requirement for young women to undergo fertility preservation treatment in clinical (Klock et al., 2010) and physiologic research (Rienzi et al., 2010) settings.

Data Collection Procedures

After participants provided written informed consent, they self-reported socio-demographic information, such as age and relationship status, on a 12-item questionnaire that was developed specifically for the study. Each participant completed the questionnaire prior to the onset of the qualitative interview to facilitate the integration of individual responses into the interview. The principal investigator (first author) conducted all qualitative interviews that began with the primary research question: Please think out loud (or write) about your decision-making experience surrounding fertility preservation. The in-depth interviews were completed based on participant preference by phone (n = 21) or by email (n = 6). The digitally-recorded phone interviews lasted 34–114 minutes (M = 58.9 minutes) and occurred at the participant’s home or other quiet, private location (e.g., her mother’s home). The phone interviews were transcribed verbatim and audio-checked for accuracy, and any errors, which were few, were corrected.

The email interviews were asynchronous. The first author emailed each of the participants the primary research question and after receiving the participant’s response would email additional interview questions and probes. The back-and-forth email cycles ranged from 2–6 asynchronous cycles per participant (M = 3.8 cycles). Details about the email procedures and equivalences between the phone and email interviews have been reported (Hershberger & Kavanaugh, 2012, April). In addition, the interviews yielded rich qualitative data about the overall decision-making processes of the participants (Hershberger, Finnegan, Pierce, & Scoccia, 2013) and how they processed information regarding fertility preservation (Hershberger, Finnegan, Altfeld et al., 2013). At completion of the interview, each participant was given a $25 gift card to a national or on-line department store.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the demographic data obtained from the responses to the 12-item questionnaires by generating means and frequencies to describe the sample. Then, to examine differences between women who accepted and women who declined fertility preservation, t-tests and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables were used respectively. We began analysis as we collected the qualitative interview data based on the tenets of grounded theory and the constant comparison approach (Charmaz, 2006). As the interviews were completed, we read them several times to gain an overall understanding and then entered them into NVivo 8 software to assist with data management and analysis. Coding of the data ensued, and the first author completed incident coding (Charmaz, 2006). As an incident (i.e., a phrase, sentence, or paragraph that provides insight) was identified in the interviews, inductive codes that described the data were assigned to each incident and grouped into emergent sub-categories. When appropriate, the descriptive codes and sub-categories were grouped (deductively) into categories that were consistent with the three dimensions (Cognitive Appraisals, Emotional Responses, Moral Judgments) of our guiding theory. Codes and sub-categories that were not consistent with the theory were assigned to emergent categories.

The first and second authors also completed an iterative and interpretative process in which qualitative codes and sub-categories were transformed into hierarchical constructs by the assignment of a quantitative numeric value (i.e., quantitizing) (Sandelowski, 2000b). The numeric value ranged from 1–5; 1 was assigned to each participant’s most important reason for accepting or declining fertility preservation based on our interpretation and analysis. Subsequent reasons were assigned values of 2–5. Limiting the hierarchical constructs to 5 versus an infinite number was consistent with the level of interpretation that the interview data provided. After the quantitizing process, we used constant comparison to guide the final analysis by all authors and to allow the existing theory to be refined, which enhanced theory development as described by Olshansky (1996) and Walker and Avant (2010).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Twenty-seven young adult women participated in the study. Fourteen declined egg, embryo, or ovarian tissue cryopreservation, and 13 accepted. The women were diagnosed with cancer on average five months (range: 1–16 months) prior to study participation. The most frequent diagnosis was breast cancer (n = 14), followed by Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 5), ovarian cancer (n = 4), and leukemia (n = 3). Other diagnoses included non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 1) and renal cancer (n = 1). One participant had two cancer types. Four of the women reported they were diagnosed previously with cancer and had received a second diagnosis of cancer within the past six months. The mean age of participants was 29 years (SD = 5.7), and participants ranged from 19–40 years of age. Further details about the sample characteristics overall and by comparison of the decision (accept or decline) are provided in Table 1. Notably, 100% of women who accepted fertility preservation did not have children, whereas only 79% of women who declined fertility preservation did not have children, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics Overall and by Decision about Fertility Preservation

| Overall N (%) |

Decline (N = 14; 51.9%) | Accept (N = 13; 48.1%) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; M ± SD) | 28.7 ± 5.66 | 29.6 ± 5.50 | 27.8 ± 5.90 | 0.419 |

| Range | (19–40) | |||

| Education (years)a | 0.369 | |||

| 12 | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 | |

| 13 | 2 (7.4%) | 0 | 2 (15.4%) | |

| 14 | 4 (14.8%) | 1 (7.1%) | 3 (23.1%) | |

| 15 | 2 (7.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| 16 | 5 (18.5%) | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| 17+ | 12 (44.4%) | 8 (57.1%) | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Income | 0.177 | |||

| Less than $30,000 | 5 (18.5%) | 1 (7.1%) | 4 (30.8%) | |

| $30,000 – $69,999 | 8 (29.6%) | 3 (21.4%) | 5 (38.5%) | |

| $70,000 – $99,999 | 6 (22.2%) | 4 (28.6%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| $100,000 or more | 8 (29.6%) | 6 (42.9%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Relationship status | 0.830 | |||

| Married | 12 (44.4%) | 7 (50.0%) | 5 (38.5%) | |

| Live with partner | 2 (7.4%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Single | 13 (48.1%) | 6 (42.9%) | 7 (53.8%) | |

| Already had children | 0.077 | |||

| No | 24 (88.9%) | 11 (78.6%) | 13 (100%) | |

| Yes | 3 (11.1%) | 3 (21.4%) | 0 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.341 | |||

| White | 21 (77.8%) | 10 (71.4%) | 11 (84.6%) | |

| African American | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (14.3%) | 0 | |

| Hispanic | 3 (11.1%) | 1 (7.1%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Mexican American | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 | |

| Employment statusb | 0.359 | |||

| Full-time | 16 (59.3%) | 9 (64.3%) | 7 (53.8%) | |

| Part-time | 2 (7.4%) | 0 | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Unemployed | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 0 | |

| Student | 9 (33.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Cancer typec | 0.257 | |||

| Breast cancer | 14 (51.9%) | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (38.5%) | |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 5 (18.5%) | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 4 (14.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Leukemia | 3 (11.1%) | 0 | 3 (23.1%) | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 (3.7%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Renal cancer | 1 (3.7%) | 0 | 1 (7.7%) |

Note.

p values derived from independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables except when Fisher’s exact tests were more appropriate given expected frequencies due to the small sample size.

One participant missing data on education.

Percentages do not sum to 100%; one individual was employed full-time and also a student.

Percentages do not sum to 100%; one individual had two types of cancer.

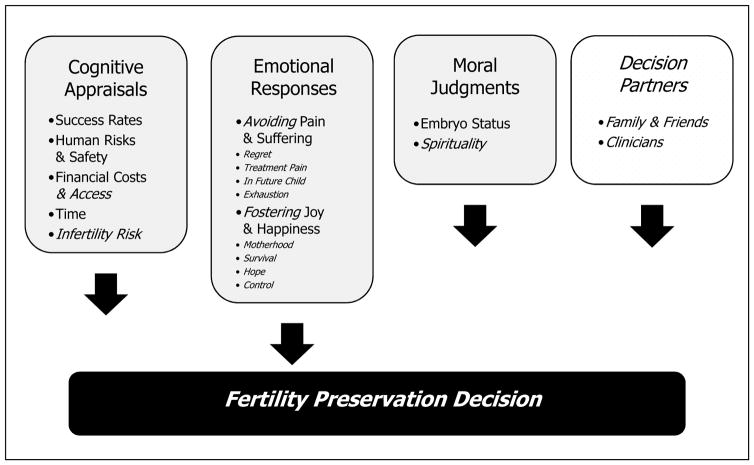

Theoretical Framework

The results indicated that the three dimensions within the PGD decision-making theory were applicable to young women’s decision making about fertility preservation following diagnosis of cancer. Our findings also demonstrated that young women’s decisions were influenced by another dimension, Decision Partners (e.g., husbands, boyfriends, mothers, parents, clinicians). Several of the categories within the three original dimensions were also clarified and refined. Figure 1 demonstrates the modified theoretical framework. In the illustrative quotes that follow, A indicates that a participant accepted fertility preservation, and D indicates that she declined.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework for Dimensions of Young Women’s Decision Making About Fertility Preservation1,2

1Framework modified from “Dimensions of Couples’ Decision Making in PGD” (Hershberger & Pierce, 2010)

2Framework modifications are noted in italics

Copyright © 2015 Fertility Decisions Research Group, reprinted with permission

Dimension 1: Cognitive Appraisals

Almost all of the participants described thinking about all of the categories (e.g., success rates, human risks and safety, financial costs and access) within the Cognitive Appraisals dimension as they reached their decisions about fertility preservation. This dimension included the most reported underlying reasons that we transformed into the top five hierarchical constructs across almost all of the accepting participants and all of the 14 declining participants. The category of Infertility Risk emerged as a new category that was not identified in prior theory development. Participants who declined fertility preservation described their top five underlying reasons in this dimension more frequently (n = 36 responses) than women who accepted fertility preservation (n = 17 responses). Of the 14 women who declined treatment, six reported categories within this dimension as the primary reason along with co-reasons (second to fifth) that affected their decisions that were most often in the categories of Financial Cost and Access, Success Rates, and Infertility Risk:

So the idea of taking a chance on a treatment that we don’t even know if it’s going to be effective … unless I knew for sure 100% I was going to be infertile and then 100% sure that it was going to work and do exactly what I wanted. I wasn’t going to spend my life saving and go bankrupt for it. (D)

What we decided was that we were going to forego the [egg] harvesting because it was too much; too much financially … in a short period of time, um, and too complicated for everything that we needed to do, in the time period that we had. (D)

Among the 13 women who accepted fertility preservation, only one woman (diagnosed with cancer a second time) described the main reasons for deciding to accept fertility preservation as the upcoming loss of her fertility due to a planned therapeutic oophorectomy and her perceived safety of the procedure. More often, young women who accepted fertility preservation described co-reasons (second to fifth) for their decisions, “You know, one of the things that I thought was really interesting, and could be challenging is that it’s very time intensive.”

The category of Time was described by the women as the length of time it takes to complete fertility preservation procedures and the length of time remaining before age-related infertility occurs. One participant who accepted was 34 and faced five years of tamoxifen treatment. She accepted because she would be almost 40 when the tamoxifen treatment ended and would therefore be at greater risk for infertility.

Regarding the category of Financial Costs and Access, because of the high out-of-pocket costs of fertility preservation, we probed participants on this topic. Participants who accepted fertility preservation and reported income less than $30,000 per year described receiving financial support through their religious communities and neighborhood fundraisers. One participant who accepted fertility preservation indicated parental support as a co-reason: “Mom and Dad have maxed out their plastic to help me to fulfill this dream” (see Dimension 4 below).

Dimension 2: Emotional Responses

In the Emotional Responses dimension, the majority of the participants who accepted (n = 12) and 11 of the participants who declined reported underlying reasons for their decisions within the two categories: Avoiding Pain and Suffering and Fostering Joy and Happiness. No new theoretical categories emerged; however, the constructs within the categories were clarified and revised to include specific sub-categories: Desire for Biological Motherhood, Hope, and Control. Many of the participants reported reasons for their decisions in this dimension, which demonstrated the overall importance of the dimension to the theoretical framework: “It - it was - it was difficult, it was frustrating, it was emotional” (D). Another participant (A) stated: “Emotional. I say this because, as a twenty-three year old newlywed facing two different cancer diagnoses and having to decide whether or not I may be able to have children in the future, how could it not be emotional?”

In the category of Fostering Joy and Happiness, eight participants who accepted fertility preservation reported desire for biological motherhood as the first reason for accepting fertility preservation. Three participants who accepted treatment reported desire for biological motherhood as second, third, or fifth reasons: “You know, I want to have kids, I hope so much one day that I can have kids, I want to have kids, I’ve always wanted to have kids, it’s not a question for me – ever.” Another participant noted the following:

I spoke with my doctor[s] and they said … that I wouldn’t be able to have kids in the future, so that really got to me because you know I kept all of my clothes from when I was little and you know, um, just little things that I’ve collected from you know, time to time, so that when I do have a kid, you know I have some stuff for my child.

In this category, participants who accepted fertility preservation also described co-reasons (second to fifth) of Hope: “So I think um, ya know, the idea of ya know, little frozen eggs and embryos waiting for me at the end of the road um, definitely gives me something to look forward to.” Two participants described how fertility preservation allowed them to maintain a sense of control following the cancer diagnosis: “I mean it [fertility preservation] is about, it’s about having a moment of control in all of it, I think.” Participants who accepted fertility preservation also placed a high emphasis on Avoiding Pain and Suffering and described a desire to avoid future regret as their primary reasons. Eight of the remaining participants who accepted fertility preservation also reported a desire to avoid future regret, although they rated this reason as third or fourth (n = 3) or fifth (n = 5). One participant explained how a desire to avoid regret played into her decision: “I told him [husband] that if we didn’t do it [fertility preservation], we might regret it, and that this was not a decision that we could take back in the future.”

Underlying reasons that aligned with the Emotional Responses dimension were also prominent among participants who declined fertility preservation. For five of these participants, the desire for biological motherhood was apparent, but they emphasized it less than participants who accepted. For example, two participants had children and described a more limited desire for motherhood, two felt motherhood could be achieved through adoption or foster parenting, and one described her strong desire to remain child free. On the other hand, participants who declined fertility preservation often reported a strong desire to survive cancer as their first or second reason (n = 5):

Well, they [clinicians] had told me, they had brought it up to me about deciding to do the preservation or not. And then, and when I found out, all I could think of was that I wanted my treatment started as soon as possible so that it wouldn’t spread. And they said, you know, even though it spreads … it does spread slowly, so you would have some time. But to me at that moment, I wanted to start [cancer] treatment as soon as possible.

Feeling mentally or physically exhausted and wanting to avoid transmission of the risk of cancer to a future child were consistent with the Avoiding Pain and Suffering category and were reported by five of the young women as co-reasons (ranked as third through fifth) for declining fertility preservation. One participant’s first reason for declining fertility preservation was a desire to avoid any future pain or stress: “And I like, pretty much immediately made the decision not to [undergo fertility preservation] because of the fact that I have to be poked and prodded again.”

Dimension 3: Moral Judgments

In this dimension, several participants reported moral reasons that affected their decisions. One described her concern about moral and ethical issues with freezing embryos as her first reason for declining: “I believe that life begins at conception and that life is sacred.” Two other participants also voiced concerns about embryo freezing as third and fifth reasons for declining. Among the participants who accepted fertility preservation, one voiced ethical concerns about freezing embryos, and she opted to freeze eggs only; another voiced concern about passing on a breast cancer gene mutation to her future child(ren) although she did not indicate that this thought significantly affected her decision.

Many of the participants indicated that moral or religious reasons did not affect their decisions: “No, it’s not really a factor at all. I would say religion had absolutely nothing to do with it,” one participant felt that God did not intend for her to be a mother, which was a co-reason (fourth) for her decision. The remaining participants alluded to the moral or religious aspects of their decision-making processes, but these were not in their top five reasons. One noted, “So I had faith, you know, God willing, it’s gonna work. Hopefully.” Based on these comments we added a category, Spirituality, and refined the original categories within this dimension of the theoretical framework.

Dimension 4: Decision Partners

Decision Partners emerged as a new dimension in the theoretical framework along with the categories of Family and Friends and Clinicians. In this dimension, 18 participants described 25 underlying reasons that involved decision partners. The reasons were related to whether they perceived support or advice from key decision partners (e.g., husbands, parents, physicians, communities) or the emphasis they placed on such advice. For instance, one participant reported that her main reason for accepting fertility preservation was trust in her clinician:

It was very clear like which options wouldn’t work [her physician discouraged ovarian tissue preservation] and which would work [physician recommended egg freezing] in my particular case, so I just kind of went along with the advice of my doctor.

For another participant, her primary reason for declining fertility preservation was lack of clinician communication and support:

So I think like the one thing I was kind of thinking of that I thought might have, would have helped, is if, you know, that maybe the doctors would have talked to me about it [fertility preservation] at a time when I was by myself.

The remaining 16 participants remarked on how support or lack of support from others, including communication barriers, served as co-reasons (second to fifth) for their decisions:

Yeah, well my boyfriend was definitely, um, he’s been my biggest support through this whole thing, and um, ya know, he knows first-hand how kind of obsessed I am with babies and family planning and ya know, everything like that. (A)

So her and I spoke about it, and I think that was also one of the more challenging factors about it, was that my mom was like adamant, you know, not to do that [fertility preservation] … and my mom and I got into a number of arguments, she thought that it was … a bad idea for me. (D)

Discussion

The reasons why young women decided to undergo fertility preservation or not are captured within the original three dimensions (Cognitive Appraisals, Emotional Responses, Moral Judgments) and a new fourth dimension (Decision Partners) of the theoretical framework. Although all four of the dimensions were important, many women delved deeply into their core values in the Emotional Responses dimension to determine whether the immediate emphasis of care should be placed on surviving cancer (declining) or securing options for future biological motherhood (accepting). Our findings did not suggest that women who declined fertility preservation were opposed to biological motherhood or that women who accepted did not want to survive cancer. Rather, the findings suggested a tension between these two choices, and the participants’ underlying reasons often aligned with one of the two. Our findings support previous studies in which women who accepted fertility preservation often described a desire for motherhood or future children (Kim et al., 2013; Partridge et al., 2004), and those who declined were often concerned with surviving cancer or minimizing cancer recurrence (Klock et al., 2010; Partridge et al., 2004).

It should be noted that for some young women, especially those who declined fertility preservation, major reasons emanated from the other three dimensions and not necessarily from the Emotional Responses dimension where the tension between surviving cancer and biological motherhood occurred. For instance, after finding out that fertility preservation involved the manipulation of gametes and embryos, one participant decided to decline; another declined because of financial reasons and the length of time needed to undergo fertility preservation, which would delay her cancer therapy. This response also illustrated how many participants who accepted or declined considered several factors within the various categories (e.g., success rates, embryo status, and clinician support) that emerged as co-reasons for their decisions. These important findings can help clinicians who care for the increasing number of individuals in unfamiliar, high-stakes, and uncertain health care situations to formulate preference-sensitive decisions that are personally relevant, informed, and meaningful (Epstein & Peters, 2009). Understanding young women’s reasons for their decisions is a first step. How these young women consider co-reasons as they make decisions remains largely unknown and is a needed area for future research.

Decision Partners emerged as a new dimension, and Family and Friends and Clinicians were two new categories within this dimension. Eighteen of the participants described reasons that were consistent with this dimension, and for many, support or lack of support or advice from family and friends served as a co-reasons for their decisions. Noteworthy is that two participants described how key decision partners, their clinicians, directly affected their decisions, which reflects the different types of shared decision making individuals prefer. In a study involving 111 women with breast cancer, Peate et al. (2011) found that a small percentage of young women (4%) preferred to leave decisions to their physicians. We did not seek to examine preferences regarding decision styles. However, given these findings, future research on preferred styles of shared decision-making could reveal important information to improve clinical counseling.

In general, egg, embryo, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation cost approximately $10,000 to $13,000 for initial treatment and an additional $300 to $600 for yearly storage fees (LIVESTRONG Foundation, n.d). Thus, we were surprised that four participants with income levels less than $30,000 accepted fertility preservation. However, these women described financial support from parents, boyfriends, and the community (e.g., religious and philanthropic groups) that offset their personal costs. Other investigators found that cost was a reason for declining treatment (Kim et al., 2013; Klock et al., 2010). Our findings extend this work and provide awareness about how low-income women navigate the financial challenges associated with fertility preservation. The findings also highlight the availability of other means of financial support when counseling young women. Because financing fertility preservation is often viewed as one of the few socially modifiable reasons that young women decline treatment, nurses should advocate for health care policies that mitigate financial challenges when young women are diagnosed with cancer.

Four women who declined treatment reported that the mental and physical energy needed to engage in fertility preservation treatment was beyond their capability, and this reason emerged as a co-reason in the Emotional Responses dimension. Klock and colleagues (2010) also reported that women who declined fertility preservation felt emotionally overwhelmed, and other investigators found that women who were undergoing treatment for infertility dropped out of care because of psychological or emotional burden (Domar, Smith, Conboy, Iannone, & Alper, 2010). Nurse clinicians and scientists are in key positions to affect the care of young women with cancer by the design, implementation, and evaluation of strategies to alleviate mental and physical burden. The use of an interdisciplinary team and members from other specialty areas, such as oncology, in an efficient systems approach can likely minimize this burden.

Limitations

Our sample was well educated, primarily White, and the predominant cancer was breast (n = 14). The lack of racial, ethnic, and educational diversity may have limited our findings; however, the sample also included two African American, one Mexican American, and three Hispanic women, and nine were college students. Our study did not include specific information about the participants’ medical stages of cancer (i.e., Stage I, Stage II), which may also limit the findings. However, our related research has shown that how patients perceive the severity of the disease or condition affects decision making more so than prescribed medical labels (e.g., Stage I, Stage II) (Hershberger et al., 2012). Nevertheless, these data provide insight into understanding decisions about fertility preservation in a sample with nearly equal distribution of women who accepted (n = 13) and who declined (n = 14). Our additional focus on delineating theoretical underpinnings provides a much needed foundation that can guide future research, especially development of quantitative survey instruments and decision support tools.

Practice Implications and Conclusions

Young women who are diagnosed with cancer often have little experience in interfacing with clinicians and the health care system. A cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming for many young women and the added complexity of deciding about future fertility can be challenging. An important finding was the significance of clinical decision partners, a role that nurses are well-positioned to fill. Nurses and other clinicians who are aware of the reasons that influence young women’s decisions about fertility preservation can use this information to assist them and to guide clinical counseling and education. For example, nurses may use hypothetical scenarios based on our results as exemplars or discussion points. In our prior research, we found that women wanted to know what others in their situations had decided and their reasons (Hershberger, Finnegan, Altfeld et al., 2013). Nurses and other clinicians can serve as key decision partners by playing active roles in the education and assistance of young women in their decision-making processes.

The number of young women diagnosed with cancer is climbing and so is the complexity that surrounds making a decision about preserving fertility prior to undergoing cancer therapy. In this study, diverse reasons that aligned with our modified decision-making framework emerged as young women considered fertility preservation. Nurses and other clinicians who are aware of young women’s underlying reasons and the tensions between these reasons can provide more tailored education and support during the decision-making process.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (K12 HD055892) and by the University of Michigan Office of the Vice President for Research. The authors thank Mary Rothring Richardson for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer treatment and survivorship facts & figures 2014–2015. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2014. Retreived from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042801.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Psychosocial problems among younger women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(5):295–308. doi: 10.1002/pon.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar U, Deal AM, Fritz MA, Kondapalli LA, Kim JY, Mersereau JE. The current fertility preservation consultation model: Are we adequately informing cancer patients of their options? Human Reproduction. 2012;27(8):2413–2419. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastings L, Baysal Ö, Beerendonk CC, IntHout J, Traas MA, Verhaak CM, Nelen WL. Deciding about fertility preservation after specialist counselling. Human Reproduction. 2014;29(8):1721–1729. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker HL. Using decision-making theory to inform clinical practice. In: Edwards A, Elwyn G, editors. Shared decision-making in health care--achieving evidence-based patient choice. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Connell S, Patterson C, Newman B. A qualitative analysis of reproductive issues raised by young Australian women with breast cancer. Health Care for Women International. 2006;27(1):94–110. doi: 10.1080/07399330500377580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danforth DN., Jr How subsequent pregnancy affects outcome in women with a prior breast cancer. Oncology. 1991;5(11):23–30. discussion 30-21, 35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domar AD, Smith K, Conboy L, Iannone M, Alper M. A prospective investigation into the reasons why insured United States patients drop out of in vitro fertilization treatment. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;94(4):1457–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand MA, Stiel M, Boivin J, Elwyn G. Where is the theory? Evaluating the theoretical frameworks described in decision support technologies. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;71(1):125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: Exploring patients’ preferences. Journal of the American Medical Associaiton. 2009;302(2):195–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LR, Balthazar U, Kim J, Mersereau JE. Trends of socioeconomic disparities in referral patterns for fertility preservation consultation. Human Reproduction. 2012;27(7):2076–2081. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MHS, Curtin SC. Births: Preliminary data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2014;63(2):1–20. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr63/nvsr63_02.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE, Finnegan L, Altfeld S, Lake S, Hirshfeld-Cytron J. Toward theoretical understanding of the fertility preservation decision-making process: Examining information processing among young women with cancer. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 2013;27(4):257–275. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.27.4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE, Finnegan L, Pierce PF, Scoccia B. The decision-making process of young adult women with cancer who considered fertility cryopreservation. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2013;42(1):59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE, Gallo AM, Kavanaugh K, Olshansky E, Schwartz A, Tur-Kaspa I. The decision-making process of genetically at-risk couples considering preimplantation genetic diagnosis: Initial findings from a grounded theory study. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;74(10):1536–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE, Kavanaugh K. E-mail interviewing methods: Procedures, equivalency, and appropriateness in two qualitative studies. Paper presented at the Midwest Nursing Research Society Annual Research Conference; Dearborn, MI. 2012. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger PE, Pierce PF. Conceptualizing couples’ decision making in PGD: Emerging cognitive, emotional, and moral dimensions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KA, Nadler T, Mandel R, Burlein-Hall S, Librach C, Glass K, Warner E. Experience of young women diagnosed with breast cancer who undergo fertility preservation consultation. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2012;12(2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukkala AM, Azuero A, McNees P, Bates GW, Meneses K. Self-assessed knowledge of treatment and fertility preservation in young women with breast cancer. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;94(6):2396–2398. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasum M, Beketić-Orešković L, Peddi PF, Orešković S, Johnson RH. Fertility after breast cancer treatment. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2014;173:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Deal AM, Balthazar U, Kondapalli LA, Gracia C, Mersereau JE. Fertility preservation consultation for women with cancer: Are we helping patients make high-quality decisions? Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2013;27(1):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King L, Quinn GP, Vadaparampil ST, Gwede CK, Miree CA, Wilson C, Perrin K. Oncology nurses’ perceptions of barriers to discussion of fertility preservation with patients with cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12(3):467–476. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klock SC, Zhang JX, Kazer RR. Fertility preservation for female cancer patients: Early clinical experience. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;94(1):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIVESTRONG Foundation. Fertility preservation options for women. Austin, TX: Author; n.d. Retrieved from http://www.livestrong.org/we-can-help/fertility-services/fertility-preservation-options-for-women/ [Google Scholar]

- Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, Brennan L, Magdalinski AJ, Partridge AH, Oktay K. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(19):2500–2510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersereau JE, Goodman LR, Deal AM, Gorman JR, Whitcomb BW, Su HI. To preserve or not to preserve: How difficult is the decision about fertility preservation? Cancer. 2013;119(22):4044–4050. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky E. Theoretical issues in building a grounded theory: Application of an example of a program of research in infertility. Qualitative Health Research. 1996;6(3):394–405. doi: 10.1177/104973239600600307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ory SJ, Devroey P, Banker M, Brinsden P, Buster J, Fiadjoe M, Sullivan E. International Federation of Fertility Societies Surveillance 2013: Preface and conclusions. Fertility and Sterility. 2014;101(6):1582–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge AH, Gelber S, Peppercorn J, Sampson E, Knudsen K, Laufer M, Winer EP. Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(20):4174–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peate M, Meiser B, Friedlander M, Zorbas H, Rovelli S, Sansom-Daly U, Hickey M. It’s now or never: Fertility-related knowledge, decision-making preferences, and treatment intentions in young women with breast cancer--an Australian fertility decision aid collaborative group study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(13):1670–1677. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peddie VL, Porter MA, Barbour R, Culligan D, MacDonald G, King D, Bhattacharya S. Factors affecting decision making about fertility preservation after cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;119(9):1049–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AH, de Vries M, Kunneman M, Stiggelbout AM, Feldman-Stewart D. Theory-informed design of values clarification methods: A cognitive psychological perspective on patient health-related decision making. Social Science and Medicine. 2013;77:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation: A committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility. 2014;101(5):1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Mature oocyte cryopreservation: A guideline. Fertility and Sterility. 2013;99(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rienzi L, Romano S, Albricci L, Maggiulli R, Capalbo A, Baroni E, Ubaldi F. Embryo development of fresh ‘versus’ vitrified metaphase II oocytes after ICSI: A prospective randomized sibling-oocyte study. Human Reproduction. 2010;25(1):66–73. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health. 2000a;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Research in Nursing and Health. 2000b;23(3):246–255. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200006)23:3<246::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing and Health. 2010;33(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/nur.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thewes B, Meiser B, Taylor A, Phillips KA, Pendlebury S, Capp A, Friedlander ML. Fertility- and menopause-related information needs of younger women with a diagnosis of early breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(22):5155–5165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudgen K, Ayensu-Coker L. Fertility preservation and reproductive health in the pediatric, adolescent, and young adult female cancer patient. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;26(5):372–380. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LO, Avant KO. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 5. Upper Saddle River: NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]