Abstract

Purpose of review

Major advances in our understanding of the genetic basis of neuroblastoma and the role somatic alterations play in driving tumor growth have led to improvements in risk-stratified therapy and have provided the rationale for targeted therapies. In this review, we highlight current risk-based treatment approaches and discuss the opportunities and challenges of translating recent genomic discoveries into the clinic.

Recent Findings

Significant progress in the treatment of neuroblastoma has been realized using risk-based treatment strategies. Outcome has improved for all patients, including those classified as high-risk, although survival remains poor for this cohort. Integration of whole-genome DNA copy number and comprehensive molecular profiles into neuroblastoma classification systems will allow more precise prognostication and refined treatment assignment. Promising treatments that include targeted systemic radiotherapy, pathway-targeted small molecules, and therapy targeted at cell surface molecules are being evaluated in clinical trials, and recent genomic discoveries in relapsed tumor samples have led to the identification of new actionable mutations.

Summary

The integration of refined treatment stratification based on whole-genome profiles with therapeutics that target the molecular drivers of malignant behavior in neuroblastoma has the potential to dramatically improve survival with decreased toxicity.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, risk classification, molecular profile, targeted therapy, immunotherapy

Introduction

Neuroblastoma is noteworthy for its broad range of clinical behavior and variable response to treatment.1 Tailored treatment approaches, based on a combination of clinical, histologic, and genetic prognostic factors have led to significant improvements in survival. However, outcome remains poor for patients classified as high-risk, with <50% achieving long-term survival.1 High-risk survivors are at risk for significant treatment-related adverse events including subsequent malignancies,2 emphasizing the critical need for more effective, less toxic treatments. In this review, we discuss recent progress in our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of the etiology and pathobiology of neuroblastoma. We also highlight “omic” profiles that offer more precise prognostic information than established classifiers, and new genomic discoveries that provide the rationale for evaluating targeted therapeutics.

Genetic Epidemiology of Neuroblastoma

Insight regarding the genetic etiology of neuroblastoma was first provided through linkage studies conducted in rare familial neuroblastoma cases. Inherited mutations in PHOX2B and ALK have been identified in these pedigrees, although disease penetrance is incomplete.3 In sporadic cases, these familial predisposition genes do not play a causative role in the vast majority of patients. Rather, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have led to the identification of common genetic variants that contribute to disease susceptibility. Interestingly, many of the susceptibility variants are associated with tumor phenotype. DUSP12, HSD17B12 and DDX4-IL31RA are associated with susceptibility to low-risk neuroblastoma, whereas single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) within or upstream of CASC15 and CASC14, BARD1, LMO1, HACE1 and LIN28B as well as a common copy-number variation (CNV) at 1q21 within NBPF23 have been shown to be highly enriched in the cohort of patients with clinically aggressive, high-risk disease.4 Further, two rare germline TP53 variants have also been associated with neuroblastoma.5 Many of these SNPs influence gene expression, and functional studies have shown that LMO1, BARD1, and LIN28 promote neuroblastoma growth.6–8 In contrast, tumor suppressor activity is associated with a short isoform of the long noncoding RNA, CASC15 (CASC15-S).9.

Common genetic variants also contribute to the higher prevalence of high-risk disease and worse outcome observed in African American children with neuroblastoma compared to Caucasians.10 Ongoing deep sequencing studies in patients with mixed lineage will lead to a deeper understanding of the genetic factors contributing to the etiology of this cancer and the disparities in survival.

Somatic Mutations

Amplification of MYCN is the most common somatic alteration in neuroblastoma. Although this oncogene was first discovered more than 30 years ago, MYCN status remains a powerful biomarker for treatment stratification today. Next-generation sequencing has revealed a relative paucity of other genomic aberrations in neuroblastoma tumors.11,12 ALK amplification and activating mutations of the ALK tyrosine kinase receptor occur in approximately 14% of all sporadic neuroblastoma, with the most frequent mutations at F1174 and R1275.13 ATRX mutations have been identified in <10% of cases, although nearly half of adolescents and young adults with neuroblastoma bear somatic mutations in this gene.14 Other recurrent mutations that occur at low frequency include heterozygous missense PTPN11 mutations12 and truncating mutations of the TIAM1 gene.11 Rare mutations in MYCN have been detected in MYCN-nonamplified tumors, and mutations in ARID1A and ARID1B have also been reported.15 Although few actionable mutations are detected at the time of diagnosis, recent studies indicate that the frequency of RAS-MAPK pathway mutations is higher in relapsed neuroblastoma, suggesting that treatments targeting this pathway may be effective in relapsed or refractory disease.16

Risk Classification

Children with neuroblastoma have received risk-based treatment for decades. To create a uniform, international pre-treatment classification algorithm, the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Task Force analyzed data collected on more than 8,800 patients and 36 prognostic factors.17 Although implementation of this system in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) and International Society of Paediatric Oncology Europe Neuroblastoma (SIOPEN)1 will facilitate comparison of risk-based clinical trials, the limitations of this algorithm are well recognized. Clinical and histologic risk criteria are merely surrogates for underlying tumor biology. Further, the individual genomic prognostic markers (MYCN and 11q status) in the INRG system were identified more than 30 years ago, before comprehensive approaches for whole genome analysis were developed. The next generation INRG Classification System is expected to be based on more current and perhaps more therapeutically applicable whole-genome and molecular biomarkers. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Current and Future INRG Classification System Variables

| INRG Classification System | INRG Classification System II | |

|---|---|---|

| INRG Stage | Tumor Genomics | DNA copy number |

| Age | mRNA expression | |

| Histological category | miRNA expression | |

| Grade of tumour differentiation | Prognostic molecular biomarkers | |

| MYCN | Therapy-specific predictive biomarkers | |

| 11q aberrations | Germline genotype | |

| DNA Ploidy | Early response to therapy | |

Genomic DNA Profiling

Whole-genome DNA copy number analyses have demonstrated that the overall genomic pattern adds significant prognostic information to conventional risk algorithms.18 Whole chromosome duplications without segmental aberrations are predictive of a favorable outcome, while inferior survival is observed in patients with tumors with segmental aberrations. The number of chromosome breakpoints is also prognostic of outcome; the presence of >7 segmental aberrations is associated with clinically aggressive disease.19

Expression Signatures

Microarray-based technologies have been used to analyze the neuroblastoma transcriptome, and a number of RNA-based signatures have been shown to have predictive power independent of conventional prognostic variables (reviewed in20). Biology-driven approaches have been used to generate a 62-hypoxia gene prognostic signature,21 and a classifier that includes genes detected in tumor-associated inflammatory cells22. Other studies have demonstrated the prognostic value of expression profiling of miRNA, other noncoding RNAs, and epigenetic modifiers.20,23 Despite the promise of these studies, molecular signatures have not been widely integrated into risk classification systems, in part due to the requirement for high-quality RNA for microarray-based assays. Digital technologies that accurately quantify gene expression using RNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissues mitigate this limitation and are more suitable clinical use.24

Advances in Risk-Stratified Therapy

An overview of the current treatment approach for non-high-risk and high-risk patients is highlighted below. Integration of molecular profiles and genomic markers that are reflective of tumor biology into future classification systems will allow more precise prognostication and refined treatment assignment.

Non-High Risk Disease

Over the past decade, efforts have been made to safely reduce therapy for patients at lower risk of relapse. Subsets of very young children have been shown to have a survival rate ≥95% without therapy.25 Outcomes for patients with localized disease (INSS 1 and 2; INRG L1) are excellent with surgery alone, provided that the tumors have no unfavorable features.26 Patients with tumors that are unresectable at diagnosis (INRGSS L2 or INSS 3 tumors) have historically been treated with systemic therapy, and the intensity of therapy has been successfully reduced in children with tumors with all favorable features.27 Further reductions in therapy are being evaluated in both European (NCT01728155) and North American trials (NCT02176967).

However, risk assessment is more complex in patients with favorable clinical features and tumors that are found to have unfavorable genomics or histology. Unlike patients with localized resectable tumors with favorable features, patients with diploid tumors or tumors with unfavorable histology have EFS rates of only 61–75% following surgery alone.26,28 Similarly, patients with localized unresectable disease whose tumors have segmental chromosome aberrations or unfavorable histology have an increased risk of relapse following moderate intensity systemic therapy.29,30 Therapy has not been reduced for infants with Stage M diploid neuroblastoma, as EFS for these patients was just 71% with moderate intensity therapy.27

High Risk Disease

Modern-era therapy for high-risk neuroblastoma has been intensified during the past decade and includes surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and immunotherapy. This multi-modality treatment is currently delivered to children >18 months of age at diagnosis who have metastatic or unresectable disease with MYCN amplification or unfavorable histology, and to children of any age with unresectable or metastatic disease in the presence of MYCN amplification. Induction consists of cycles of multi-agent chemotherapy and primary tumor resection.1 Initial therapy is followed by an augmented consolidation consisting of high dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue (ASCR) and external beam radiation. While ASCR has been shown to improve EFS in large, randomized trials, OS has not improved in patients enrolled on ASCR-containing regimens.31,32 This highlights the need to develop treatments that will improve survival for patients with high-risk disease, and to refine our approach to treatment assignment so that maximally intensive myeloablative therapy is only delivered to those most likely to derive benefit.

Upon recovery from ASCR, external beam radiotherapy is administered. High rates of disease site control have been reported following radiation to the primary tumor bed and sites of persistent metastatic disease (5 year site-specific control rates of 84% and 74%, respectively).33 Among patients with relapsed disease, recurrence in bony sites present at diagnosis and treated with radiation was less frequent than recurrence in sites not radiated (16% vs 25%).34 Rates of toxicity to viscerae are low following modern-era radiotherapy, however radiation may be linked to bone changes and second malignancies in survivors of high-risk disease.2,35 Identification of markers of radiation responsiveness in neuroblastoma tumors may be helpful in radiation-related decision-making in the future.

Post-consolidation therapy is designed to treat minimal residual disease, and includes administration of dinutuximab, a chimeric antibody directed against the cell surface ganglioside GD2. A randomized COG trial showed improved survival in patients assigned to receive dinutuximab in combination with cytokines (granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor and interleukin-2) and the differentiating agent isotretinoin than in those randomized to isotretinoin alone (2-year EFS 66% versus 46%; 2-year OS 86% versus 75%).36 Strategies to optimize administration of adjuvants that enhance the activity of dinutuximab are being studied in Europe (NCT01704716). Toxicities associated with this post-consolidation regimen are non-trivial; patients frequently experience pain, allergic reactions, blood pressure changes, and fevers. Analysis of the relationship between anti-glycan antibodies and the incidence of allergic reactions is in progress, as are studies to identify Fcγ Receptor, Killer Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR), and KIR ligand polymorphisms associated with the efficacy of GD2-directed therapy.37 In addition, because high levels of the immunosuppressive NKp30c isoform and its ligand B7-H6 have been associated with unfavorable outcomes in children with neuroblastoma,38 studies of the relationship between NKp30 isoform patterns and outcome following immunotherapy are ongoing.

Relapsed Disease

Disease recurrence continues to present a major therapeutic challenge. Approximately 50% of children with high-risk disease will relapse, and 5-year OS among those who relapse is only 8%.39 Several approaches to targeted therapy for relapsed neuroblastoma have been explored, including targeted systemic radiotherapy, pathway-targeted small molecules, and therapy targeted at cell surface molecules.

Targeted radiotherapy

Approximately 90% of neuroblastoma tumors take up radioactive meta-iodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG). This norepinephrine analog has been extensively studied in relapsed and refractory disease.1 Radiation sensitizers including irinotecan and vorinostat may augment response to 131I-MIBG and are being evaluated in a randomized trial (NCT02035137), and 131I-MIBG is being evaluated in a frontline COG pilot trial (NCT01175356). 131I-MIBG will be studied in Europe in combination with Busulfan/Melphalan ASCR in patients with suboptimal responses to initial therapy, and will be evaluated in COG as part of induction. While tumor norepinephrine transporter (NET) expression appears to correlate with MIBG avidity,40 the relationship between NET expression and response to therapy is unknown. Analysis of NET expression and other potential markers of sensitivity to 131I-MIBG will be important as trials proceed.

Pathway Targeted Therapy

Relatively few somatic mutations have been detected in primary neuroblastoma tumors at the time of diagnosis,11,12 though the frequency of mutations is higher at relapse.41 Activating mutations in the Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) are observed in 8% of neuroblastomas at diagnosis,13 but may be detected more frequently at relapse.42 Inhibitors of ALK kinase activity have been developed, including the ALK/MET inhibitor crizotinib. A study of crizotinib in combination with chemotherapy is underway (NCT01606878), as are early phase trials of next-generation ALK inhibitors (NCT01742286 and NCT02097810). Other kinase inhibitors are also in development. Detection of an increased number of RAS-MAPK mutations in tumors at relapse16 has increased interest in inhibitors of signaling molecules in this pathway. Several MEK inhibitors are being evaluated, and a pediatric trial of trametinib (NCT02124772) has recently begun.

Amplification of MYCN remains the most common somatic alteration in neuroblastoma tumors, and multiple approaches to alteration of MYCN expression have been explored. Aurora A kinase modulates stability of the MYCN protein and activity of the Aurora A kinase inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237) was seen in preclinical models.43,44 This agent is being evaluated in combination with chemotherapy in an ongoing trial (NCT01601535). Components of the PI3K/AKT pathway have also been shown to modulate the stability of the MYCN protein and are candidates for further study (reviewed in45). In addition, downstream targets of MYCN are being evaluated. Ornithine decarboxylase 1 (ODC1) is a MYC target gene, and ODC1 is a key regulator of polyamine synthesis within cells. An inhibitor of ODC1, α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), increases tumor-free survival in preclinical neuroblastoma models.46 This agent is being evaluated in combination with chemotherapy in an early phase trial (NCT02030964).

Cell Surface Molecules as Targets for Therapy

The most successful strategy for targeting of cell surface molecules has been ganglioside-directed therapy. In addition to the chimeric antibody dinutuximab, other anti-GD2 antibodies have been developed, including murine and humanized antibodies.(reviewed in47) GD2-directed antibodies are being studied with cytokines, cellular immune effectors, other immune modulators, and chemotherapeutics (NCT01757626, NCT00877110, NCT00911560, NCT01711554, NCT01767194). An alternative approach to GD2-directed neuroblastoma therapy makes use of effector lymphocytes modified to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). The presence of a GD2-specific extracellular single-chain variable fragment allows for major histocompatibility complex-independent tumor antigen recognition and T cell stimulation. Activity of GD2 CARs has been reported in preclinical models, and initial clinical studies have demonstrated the safety of this approach (reviewed in48). Additional GD2 CAR studies are underway (NCT01822652, NCT02107963) or in development. Other cell surface antigens provide alternative targets for CAR T cell therapy for neuroblastoma, including the adhesion molecule CD171 (L1-CAM).49 Evaluation of additional cell surface targets is an active area of research.(reviewed in50)

Conclusion

Correlative science has been an integral part of neuroblastoma trials for decades, and significant progress in our understanding of the epidemiology and pathobiology of this disease has been gained through the use of well-annotated biobank samples. However, a substantial gap exists between the discovery of molecular drivers of malignant behavior and our ability to translate this knowledge into less toxic, more effective therapy. As we look to the future, it is clear that alterations in DNA sequence in tumor cells alone will not provide all of the information we need to improve outcomes. Instead, we must also take into account data generated through expression profiling, epigenetic analyses, proteomic studies, and host germline alterations to understand and predict the behavior of this malignancy in a comprehensive way. Furthermore, we must develop robust predictive biomarkers to identify patients who will benefit most from components of modern neuroblastoma therapy. Use of a larger number of prognostic factors and biomarkers will provide rationale for therapy tailored to ever-smaller subsets of patients. However, experience suggests that rational therapies cannot be assumed to be effective without being tested in prospectively studies. Design of new-era clinical trials for very small groups of children with neuroblastoma represents the next frontier in investigation.

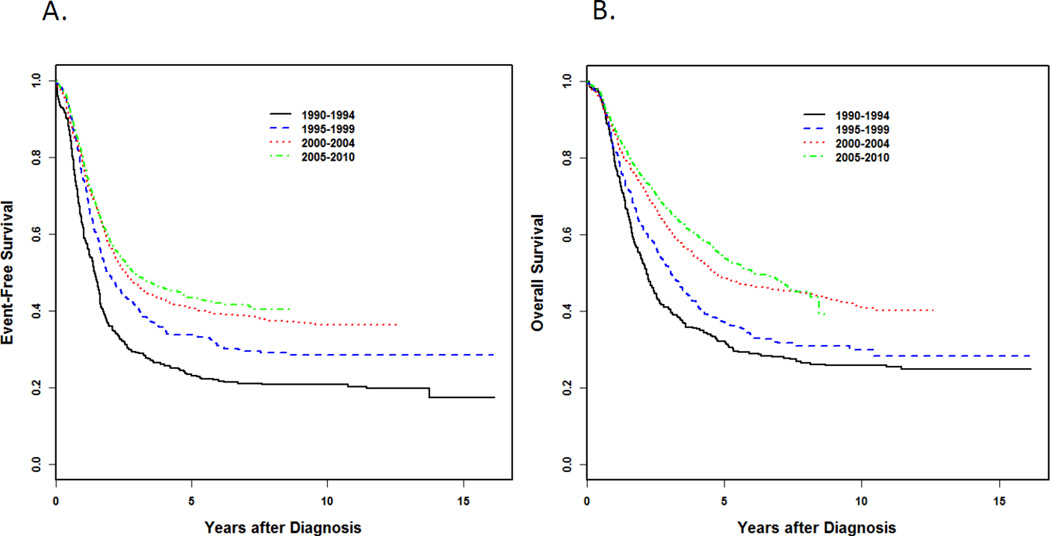

Figure 1.

Probability of event-free survival (EFS) (A) and overall survival (OS) (B) among 3,352 Children's Oncology Group (COG) patients with high-risk neuroblastoma diagnosed between 1990 and 2010 according to era. 356 patients were diagnosed between 1990 and 1994; 497 were diagnosed from 1995 to 1999; 1,105 were diagnosed from 2000 to 2004, and 1,484 were diagnosed from 2005 to 2010. (Data provided by the COG Statistics and Data Center.)

(Reused with permission. © 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved. Pinto NR, et al.: J Clin Oncol. 2015 Aug 24. pii: JCO.2014.59.4648. [Epub ahead of print])

Key Points.

Risk-based treatment has led to improved survival for patients with neuroblastoma, but survival for high-risk patients remains poor.

The prognostic criteria integrated into current risk classification systems have significant limitations, and more robust predictive biomarkers are needed to identify patients who will benefit most from components of modern neuroblastoma therapy.

Significant progress in our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of the etiology and pathobiology of neuroblastoma has been gained through the use of well-annotated biobank samples.

A substantial gap remains between the discovery of molecular drivers of malignant behavior and our ability to translate this knowledge into less toxic, more effective therapy.

Integration of refined treatment stratification based on whole-genome profiles with therapeutics that target the molecular drivers of malignant behavior in neuroblastoma has the potential to dramatically improve the survival of children with high-risk neuroblastoma.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported in part by the U10-CA98543 COG Group Chair’s grant; the St. Baldrick’s Foundation (SLC); Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation (SLC); the William Guy Forbeck Research Foundation (SLC); the Little Heroes Cancer Research Fund (SLC); The Children’s Neuroblastoma Cancer Foundation (SLC); The Neuroblastoma Children’s Cancer Foundation (SLC)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Susan L. Cohn: Equity ownership: United Therapeutics, Pfizer, Novartis United Therapeutics Advisory Board

References

- 1. Pinto NR, Applebaum MA, Volchenboum SL, et al. Advances in Risk Classification and Treatment Strategies for Neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4648. *This review provides an update of the advances in risk classification and stratified treatment approaches that have resulted from studies conducted by collaborative institutions and international cooperative groups. The significant progress in our understanding of the epidemiology and pathobiology of this disease gained through the use of well-annotated biobank samples collected by the cooperative groups is also highlighted.

- 2.Applebaum MA, Henderson TO, Lee SM, et al. Second malignancies in patients with neuroblastoma: the effects of risk-based therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:128–133. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devoto M, Specchia C, Laudenslager M, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis to identify genetic modifiers of ALK mutation penetrance in familial neuroblastoma. Hum Hered. 2011;71:135–139. doi: 10.1159/000324843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capasso M, Diskin SJ, Totaro F, et al. Replication of GWAS-identified neuroblastoma risk loci strengthens the role of BARD1 and affirms the cumulative effect of genetic variations on disease susceptibility. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:605–611. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diskin SJ, Capasso M, Diamond M, et al. Rare variants in TP53 and susceptibility to neuroblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju047. dju047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang K, Diskin SJ, Zhang H, et al. Integrative genomics identifies LMO1 as a neuroblastoma oncogene. Nature. 2011;469:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature09609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diskin SJ, Capasso M, Schnepp RW, et al. Common variation at 6q16 within HACE1 and LIN28B influences susceptibility to neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosse KR, Diskin SJ, Cole KA, et al. Common variation at BARD1 results in the expression of an oncogenic isoform that influences neuroblastoma susceptibility and oncogenicity. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2068–2078. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Russell MR, Penikis A, Oldridge DA, et al. CASC15-S Is a Tumor Suppressor lncRNA at the 6p22 Neuroblastoma Susceptibility Locus. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3155–3166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3613. *The authors report that the highly significant neuroblastoma susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) on chromosome 6p22 reside in CASC15, a long noncoding RNA. A short CASC15 isoform (CASC15-S) appears to mediate neural growth and differentiation, leading to tumor suppression.

- 10.Gamazon ER, Pinto N, Konkashbaev A, et al. Trans-population analysis of genetic mechanisms of ethnic disparities in neuroblastoma survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:302–309. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molenaar JJ, Koster J, Zwijnenburg DA, et al. Sequencing of neuroblastoma identifies chromothripsis and defects in neuritogenesis genes. Nature. 2012;483:589–593. doi: 10.1038/nature10910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pugh TJ, Morozova O, Attiyeh EF, et al. The genetic landscape of high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:279–284. doi: 10.1038/ng.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bresler SC, Weiser DA, Huwe PJ, et al. ALK mutations confer differential oncogenic activation and sensitivity to ALK inhibition therapy in neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:682–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.019. **A comprehensive genomic, biochemical, and computational analyses of ALK mutations across 1,596 diagnostic neuroblastoma samples. Oncogenic versus non-oncogenic mutations were identified, and the mutated variants showed differential in vitro crizotinib sensitivities. These findings have therapeutic implications regarding the selection of ALK-targeted therapy for specific mutations.

- 14.Cheung NK, Zhang J, Lu C, et al. Association of age at diagnosis and genetic mutations in patients with neuroblastoma. JAMA. 2012;307:1062–1071. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sausen M, Leary RJ, Jones S, et al. Integrated genomic analyses identify ARID1A and ARID1B alterations in the childhood cancer neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:12–17. doi: 10.1038/ng.2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eleveld TF, Oldridge DA, Bernard V, et al. Relapsed neuroblastomas show frequent RAS-MAPK pathway mutations. Nat Genet. 2015;47:864–871. doi: 10.1038/ng.3333. **Whole-genome sequencing of paired diagnostic and relapse neuroblastomas showed clonal evolution from the diagnostic tumor. The majority of mutations in relapsed tumors were predicted to activate the RAS-MAPK pathway and were sensitive to MEK inhibition. These findings highlight the potential clinical relevance of RAS-MAPK pathway mutations.

- 17.Cohn SL, Pearson AD, London WB, et al. The International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system: an INRG Task Force report. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:289–297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Schleiermacher G, Michels E, et al. Overall genomic pattern is a predictor of outcome in neuroblastoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:1026–1033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schleiermacher G, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Ribeiro A, et al. Accumulation of segmental alterations determines progression in neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3122–3130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schleiermacher G, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Delattre O. Recent insights into the biology of neuroblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2249–2261. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fardin P, Barla A, Mosci S, et al. A biology-driven approach identifies the hypoxia gene signature as a predictor of the outcome of neuroblastoma patients. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:185. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asgharzadeh S, Salo JA, Ji L, et al. Clinical significance of tumor-associated inflammatory cells in metastatic neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3525–3532. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Preter K, Mestdagh P, Vermeulen J, et al. miRNA expression profiling enables risk stratification in archived and fresh neuroblastoma tumor samples. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7684–7692. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stricker TP, Morales La Madrid A, Chlenski A, et al. Validation of a prognostic multi-gene signature in high-risk neuroblastoma using the high throughput digital NanoString nCounter system. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.010. * This study validated the the prognostic significance of a 42-gene microarray signature using high throughput digital technology and formulin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) neuroblastoma tumor samples. Use of FFPE tissues in lieu of frozen tumor will facilitate the clinical use of molecular profiling data for treatment decisions.

- 25.Nuchtern JG, London WB, Barnewolt CE, et al. A prospective study of expectant observation as primary therapy for neuroblastoma in young infants: a Children's Oncology Group study. Ann Surg. 2012;256:573–580. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826cbbbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strother DR, London WB, Schmidt ML, et al. Outcome after surgery alone or with restricted use of chemotherapy for patients with low-risk neuroblastoma: results of Children's Oncology Group study P9641. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1842–1848. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker DL, Schmidt ML, Cohn SL, et al. Outcome after reduced chemotherapy for intermediate-risk neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1313–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Bernardi B, Mosseri V, Rubie H, et al. Treatment of localised resectable neuroblastoma. Results of the LNESG1 study by the SIOP Europe Neuroblastoma Group. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1027–1033. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schleiermacher G, Michon J, Ribeiro A, et al. Segmental chromosomal alterations lead to a higher risk of relapse in infants with MYCN-non-amplified localised unresectable/disseminated neuroblastoma (a SIOPEN collaborative study) Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1940–1948. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohler JA, Rubie H, Castel V, et al. Treatment of children over the age of one year with unresectable localised neuroblastoma without MYCN amplification: results of the SIOPEN study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3671–3679. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Long-term results for children with high-risk neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13-cis-retinoic acid: a children's oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8925. Errata June 10, 2014: 1862–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berthold F, Boos J, Burdach S, et al. Myeloablative megatherapy with autologous stem-cell rescue versus oral maintenance chemotherapy as consolidation treatment in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:649–658. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mazloom A, Louis CU, Nuchtern J, et al. Radiation therapy to the primary and postinduction chemotherapy MIBG-avid sites in high-risk neuroblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:858–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.07.019. *Site specific local control rates following radiation to the primary tumor bed and a limited number of sites of persistent metastatic disease were evaluated in this single instutition study. A systematic approach to external beam radiotherapy resulted in high site-specific disease control rates.

- 34. Polishchuk AL, Li R, Hill-Kayser C, et al. Likelihood of bone recurrence in prior sites of metastasis in patients with high-risk neuroblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:839–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.04.004. *This multi-center study of children with relapsed neuroblastoma evaluated sites of relapse in detail. The incidence of relapse in sites of disease present at diagnosis and treated with external beam radiation was lower than the incidence of relapse in sites that were not irradiated.

- 35.Yu JI, Lim do H, Jung SH, et al. The effects of radiation therapy on height and spine MRI characteristics in children with neuroblastoma. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delgado DC, Hank JA, Kolesar J, et al. Genotypes of NK cell KIR receptors, their ligands, and Fcgamma receptors in the response of neuroblastoma patients to Hu14.18-IL2 immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9554–9561. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Semeraro M, Rusakiewicz S, Minard-Colin V, et al. Clinical impact of the NKp30/B7-H6 axis in high-risk neuroblastoma patients. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:283ra55. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2327. *This study evaluated the relative expression of isoforms of NKp30 in peripheral blood from children with neuroblastoma and assessed expression of the NKp30 ligand B7H6 in neuroblastoma cells. NKp30 isoform expression correlated with EFS in children with chemotherapy responsive disease appears to have prognostic and potentially therapeutic significance.

- 39.London WB, Castel V, Monclair T, et al. Clinical and biologic features predictive of survival after relapse of neuroblastoma: a report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group project. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3286–3292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubois SG, Geier E, Batra V, et al. Evaluation of Norepinephrine Transporter Expression and Metaiodobenzylguanidine Avidity in Neuroblastoma: A Report from the Children's Oncology Group. Int J Mol Imaging. 2012;2012:250834. doi: 10.1155/2012/250834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schramm A, Koster J, Assenov Y, et al. Mutational dynamics between primary and relapse neuroblastomas. Nat Genet. 2015;47:872–877. doi: 10.1038/ng.3349. **Integrated genomic profiling was performed in patients with neuroblastoma using tumor tissue from diagnois and relapse, as well as constitutional DNA. More mutations were seen at the time of relapse, and some of the recurrent events observed at relapse may represent therapeutic opportunities.

- 42. Schleiermacher G, Javanmardi N, Bernard V, et al. Emergence of new ALK mutations at relapse of neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2727–2734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0674. *This study of tumors obtained at diagnosis and at relapsed shows that subclonal ALK mutations can be present at diagnosis with later clonal expansion detectable at relapse. This finding has therapeutic significance due to the development of ALK-targeted agents.

- 43.Otto T, Horn S, Brockmann M, et al. Stabilization of N-Myc is a critical function of Aurora A in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maris JM, Morton CL, Gorlick R, et al. Initial testing of the aurora kinase A inhibitor MLN8237 by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:26–34. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustafson WC, Weiss WA. Myc proteins as therapeutic targets. Oncogene. 2010;29:1249–1259. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evageliou NF, Hogarty MD. Disrupting polyamine homeostasis as a therapeutic strategy for neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5956–5961. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dobrenkov K, Cheung NK. GD2-targeted immunotherapy and radioimmunotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:589–612. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.07.003. *This review provides an overview of GD2 directed monoclonal antibody therapy, GD2 vaccines, and GD2 directed immunocytokine constructs, and summarizes lessons learned from trials of anti-GD2 therapies conducted to date. Emerging GD2 targeted therapeutics are also discussed.

- 48.Heczey A, Louis CU. Advances in chimeric antigen receptor immunotherapy for neuroblastoma. Discov Med. 2013;16:287–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hong H, Stastny M, Brown C, et al. Diverse solid tumors expressing a restricted epitope of L1-CAM can be targeted by chimeric antigen receptor redirected T lymphocytes. J Immunother. 2014;37:93–104. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000018. *This study of the expression of the CE7R epitope of L1-CAM in tumor cell lines, primary tumor tissues, and normal tissues revealed that this epitope is widely expressed across multiple tumor types (including neuroblastoma) but has restricted expression in normal tissues outside of the central nervous system. This suggests that CE7-targeted therapy is likely to be well tolerated and have broad clincal applications.

- 50.Orentas RJ, Lee DW, Mackall C. Immunotherapy targets in pediatric cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:3. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]