Abstract

C1q-binding ability may indicate the clinical relevance of de novo donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies (DSA). This study investigated the incidence and risk factors for the appearance of C1q-binding de novo DSA and their long-term impact. Using Luminex Single Antigen Flow Bead assays, 346 pretransplant nonsensitized kidney recipients were screened at 2 and 5 years after transplantation for de novo DSA, which was followed when positive by a C1q Luminex assay. At 2 and 5 years, 12 (3.5%) and eight (2.5%) patients, respectively, had C1q-binding de novo DSA. De novo DSA mean fluorescence intensity >6237 and >10,000 at 2 and 5 years, respectively, predicted C1q binding. HLA mismatches and cyclosporine A were independently associated with increased risk of C1q-binding de novo DSA. When de novo DSA were analyzed at 2 years, the 5-year death-censored graft survival was similar between patients with C1q-nonbinding de novo DSA and those without de novo DSA, but was lower for patients with C1q-binding de novo DSA (P=0.003). When de novo DSA were analyzed at 2 and 5 years, the 10-year death-censored graft survival was lower for patients with C1q-nonbinding de novo DSA detected at both 2 and 5 years (P<0.001) and for patients with C1q-binding de novo DSA (P=0.002) than for patients without de novo DSA. These results were partially confirmed in two validation cohorts. In conclusion, C1q-binding de novo DSA are associated with graft loss occurring quickly after their appearance. However, the long-term persistence of C1q-nonbinding de novo DSA could lead to lower graft survival.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, de novo donor specific antibodies, C1q, complement, graft survival

The humoral arm of the immune system is accountable for most of the decline in kidney allograft function, leading to graft loss.1–3 Donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) identified before transplantation in patients already sensitized are associated with early antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) and poorer graft survival.4,5 Alternatively, de novo DSAs (dnDSAs) emerge after transplantation in 13%–27% of previously nonsensitized recipients when detected with current highly sensitive single-antigen flow beads (SAFB) assays.6,7 They mostly appear during the first year7 but also up to 10 years later.8,9 Most dnDSA are anti–class II.6,8 The putative risk factors are young recipient age, HLA mismatches, deceased donor, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor–based immunosuppression and nonadherence to treatment.6,8–10 dnDSA are associated with acute and chronic antibody-mediated renal lesions,6,7,9,11,12 chronic graft dysfunction,6 and lower graft survival.6–9

Because a fraction of dnDSA-positive patients escape rejection or graft dysfunction,9,13 the current challenge is to identify clinically relevant dnDSAs in order to better stratify the individual immunologic risk. Several proposed approaches rely on serum dnDSA SAFB mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) strength,14,15 IgG subclass analysis,16 or complement-binding ability.17,18 DSAs are deleterious via different pathways, but complement C4d deposition in peritubular capillaries reflects the central role of complement in AMR endothelial cell aggression. Because C1q is the complement classic pathway’s first protagonist, C1q-binding ability could be a hallmark for clinically relevant serum dnDSA. Very little is known about C1q-binding (C1q+) dnDSA incidence, and no risk factors for their appearance have been reported. There is no consensus about the correlation between dnDSA SAFB MFI levels and C1q-binding ability.15,17 Until recently, the prognostic value of C1q+ dnDSA had been assessed in only two studies,15,19 but a large, recently held study showed that C1q+ dnDSA conferred a higher risk of kidney allograft loss than C1q− dnDSA. However, that study described neither the kinetics of DSA ability to bind C1q over time nor the long-term effect of both C1q+ and C1q− dnDSA.20

Our objectives were to describe the kinetics of C1q-binding ability of dnDSA at 2 and 5 years after transplantation, the risk factors associated with their appearance, and the long-term effect of both C1q+ and C1q− dnDSA in a population of pretransplant nonsensitized kidney recipients.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

This study included 346 recipients. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All were non-HLA–sensitized before transplantation and received a deceased-donor primary transplant. At 2 years after transplantation, 20 (6%) had experienced at least one borderline rejection episode, 43 (12%) had at least one biopsy-proven T cell–mediated rejection episode, and five (1.4%) had a clinical acute AMR episode. Mean follow-up duration (±SD) was 109±34 months.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n=346)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 47±13 |

| Women/men | 93/253 (27/73) |

| Nephropathy | |

| Diabetes | 15 (4) |

| IgA | 44 (13) |

| Other glomerular | 87 (25) |

| Interstitial | 44 (13) |

| Vascular | 30 (9) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 58 (17) |

| Other hereditary | 41 (12) |

| Unknown | 22 (6) |

| Other | 5 (1) |

| Time on waiting list (mo) | 20±18 |

| Dialysis duration (mo) | 31±31 |

| Hemodialysis/peritoneal dialysis | 317 (94)/20 (6) |

| Primary transplant | 346 (100) |

| Deceased donor | 346 (100) |

| Donor age (yr) | 42±14 |

| Extended-criteria donor (%) | 72 (22) |

| Total ischemia time (h) | 18±8 |

| No. of HLA A-B-DR-DQ mismatches | 2.6±1.3 |

| No. of HLA DQ mismatches | 0.5±0.6 |

| Delayed graft function | 79 (23) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs at day 0 (n=346) | |

| Induction: Daclizumab/antithymocyte globulins/no | 212 (61)/47 (14)/87 (25) |

| Drug 1: Cyclosporine A/tacrolimus/sirolimus/belatacept | 229 (67)/111 (32)/3 (1)/1 (0) |

| Drug 2: MMF/azathioprine/everolimus/FTY | 312 (91)/30 (9)/1 (0)/1 (0) |

| Steroids | 346 (100) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs at year 2 (n=342) | |

| Drug 1: Cyclosporine A/tacrolimus/sirolimus/belatacept | 169 (49)/164 (48)/8 (2)/1 (1) |

| Drug 2: MMF/azathioprine | 296 (90)/32 (10) |

| Steroids | 174 (51) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs at year 5 (n=316) | |

| Drug 1: Cyclosporine A/ Tacrolimus/ mTOR inhibitors/ Belatacept | 143 (45)/159 (50)/13 (4)/1 (1) |

| Drug 2: MMF/Azathioprine/ 0 | 263 (83)/38 (12)/15 (5) |

| Steroids | 137 (40) |

Unless otherwise noted, values are the number (percentage) of patients. Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD. MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; FTY, FTY720; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

dnDSA at 2 Years after Transplantation

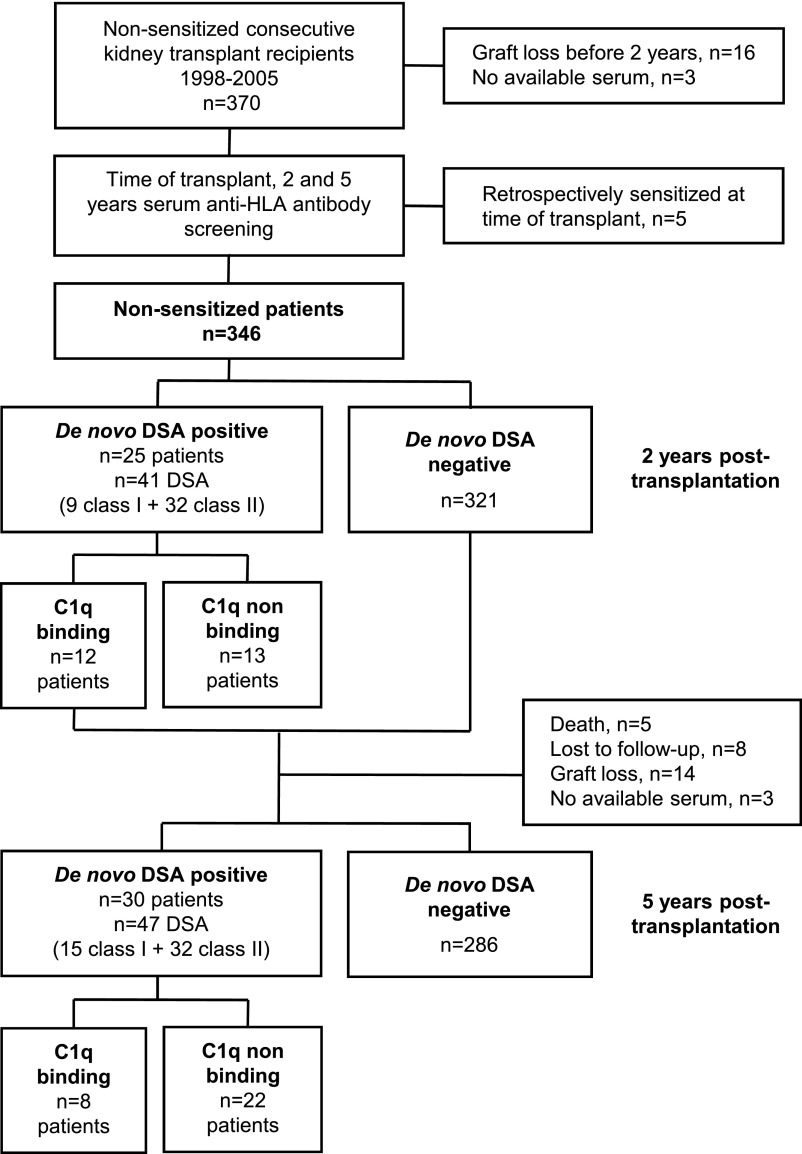

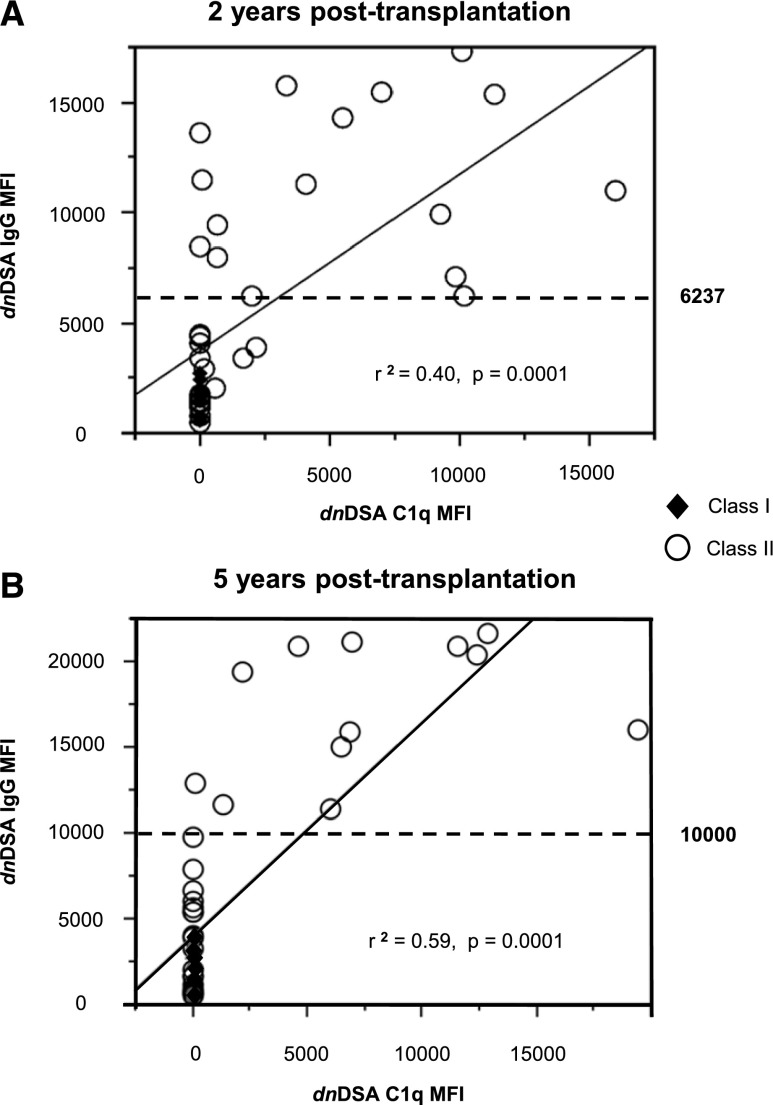

At 2 years after transplantation (Figure 1), 25 (7%) patients had a total of 41 dnDSAs (average, 1.6 dnDSAs per patient). Among them, six (1.7%), 21 (6%), and two (0.6%) had class I, class II, and class I+II dnDSAs, whose median (range) MFIs were 1500 (565–2703) and 5538 (516–17348) for class I and class II, respectively. Twelve (3.5%) patients had C1q+ dnDSAs (average, 1.5 C1q+ dnDSAs per patient). Two patients with both C1q+ and C1q− dnDSAs were classified as C1q+ dnDSA patients. Among the 41 dnDSAs, 18 (43%) were C1q+—all class II (three anti-DR and 15 anti-DQ). The 23 C1q− dnDSAs targeted both class I and class II antigens (six anti-A, one anti-B, 2 anti-Cw, five anti-DR, eight anti-DQ, and one anti-DP). dnDSA MFI was correlated with C1q binding ability (r2=0.40; P<0.001) (Figure 2A). A receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis (result not shown) showed that a dnDSA MFI threshold of 6237 predicted the presence of C1q+ dnDSA with sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of 78%, 91%, 87.5%, and 84%, respectively (area under curve, 0.91). Four patients had C1q+ dnDSAs with an SAFB IgG MFI<6237. Serum pretreatment with EDTA revealed an SAFB IgG MFI far above this threshold in all four patients (Table 2). EDTA pretreatment was not performed for the other sera. No class I dnDSA was C1q+, but class I dnDSA MFI was <6237.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. Patient distribution according to the presence of dnDSAs and C1q-binding dnDSA (C1q+ dnDSA), as well as the number of dnDSAs. dnDSAs were screened at 2 and 5 years after transplantation in 346 and 316 patients, respectively. Two patients at 2 years and one patient at 5 years after transplantation had both C1q+ and C1q− dnDSA.

Figure 2.

Correlation between IgG MFI and C1q MFI of dnDSAs. Class I (diamonds) and class II (circles) dnDSAs detected at 2 (A) and 5 (B) years after transplantation. Solid lines represent correlation between IgG MFI and C1q assay MFI. Dashed lines represent the MFI threshold predictive of C1q binding, as determined by a receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis at 2 years after transplantation. The threshold was obvious at 5 years after transplantation.

Table 2.

Effect of serum preincubation with EDTA on MFI of C1q-binding dnDSA: evidence for a prozone phenomenon in low MFI DSAs found to be C1q+ DSAs

| Patient No. | Target Antigen | SAFB (MFI) | SAFB-EDTA (MFI) | C1q-Binding assay (MFI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DR53 | 2049 | 10,739 | 565 |

| 2 | DQ7 | 2964 | 8414 | 177 |

| 3 | DQ7 | 3435 | 6464 | 1650 |

| 4 | DQ α chain | 3878 | 6748 | 2182 |

dnDSA at 2 Years after Transplantation and Clinical Outcome at 5 Years

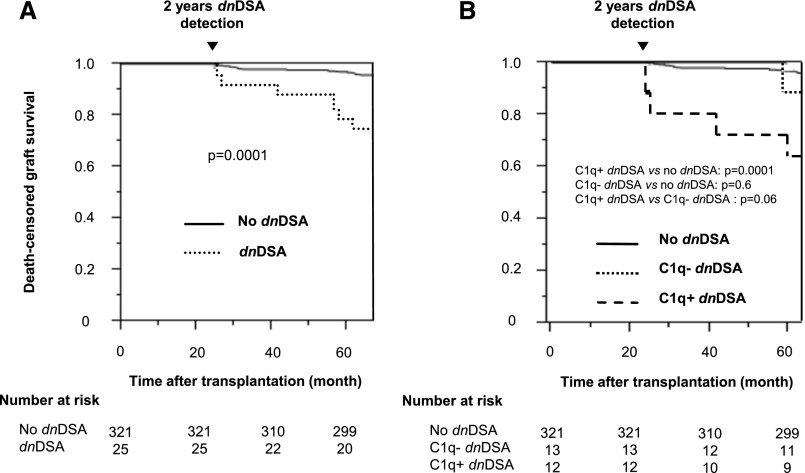

Acute AMR occurred in seven additional patients after 2 years, none of whom had dnDSA at 2 years. The eGFR at 1, 2, and 5 years after transplantation was similar between patients without dnDSA, with C1q+ or C1q− dnDSA (Supplemental Table 1). Patients with dnDSAs at 2 years had a poorer 5-year death-censored graft survival than those without dnDSAs (P<0.001) (Figure 3A), with no difference between class I and class II (result not shown). The 5-year death-censored graft survival rate was lower in patients with C1q+ dnDSAs than in those without dnDSAs (67% and 97%, respectively; P<0.001) but was similar between patients with C1q− dnDSA (92%) and without dnDSA (P=0.6) (Figure 3B). The five patients who died between 2 and 5 years were all in the no dnDSA group (P=0.8).

Figure 3.

Death-censored graft survival according to the presence of dnDSAs detected at 2 years after transplantation. (A) Patients with and without dnDSAs. (B) Patients with C1q+ dnDSAs, C1q− dnDSAs, and without dnDSAs.

dnDSA at 5 Years after Transplantation

At 5 years after transplantation (Figure 1), 316 patients were alive with a functioning graft and an available serum sample. Among them, 30 (9.3%) had a total of 47 dnDSAs (average, 1.6 dnDSAs per patient). Overall, 12 (3.7%), 22 (6.9%), and four (1.2%) patients had class I, class II, and class I+II dnDSAs, whose median (range) MFIs were 1322 (566–3970) and 5959 (533–21599) for class I and class II, respectively. Only 8 (2.5%) patients had C1q+ dnDSAs (average, 1.5 dnDSAs per patient), one of whom had C1q+ and C1q− class II dnDSA. Among the 47 dnDSAs, 12 (25.5%) were C1q+, all against HLA-DQ. The 35 C1q− dnDSA targeted both class I and class II antigens (anti-A, seven; anti-B, four; anti-Cw, four; anti-DR, seven; anti-DQ, 12; anti-DP, one). DnDSA MFI was correlated with C1q binding ability (r2=0.59; P<0.001) (Figure 2B). All C1q+ and all C1q− dnDSAs displayed an SAFB MFI >10,000 and <10,000, respectively. No class I dnDSA was C1q+, but all class I dnDSA MFI values were <10,000.

Evolution of dnDSA between 2 and 5 Years after Transplantation

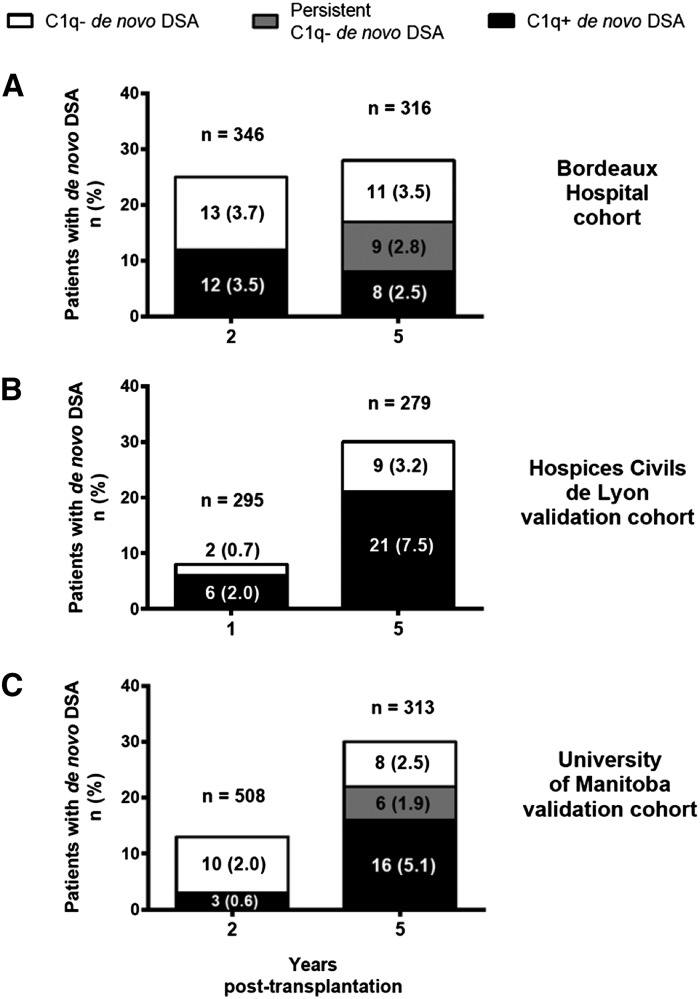

Among the 321 patients without dnDSA at 2 years after transplantation, 283 (88%) still had no dnDSAs at 5 years, but 11 (3%) and two (1%) developed C1q− and C1q+ dnDSAs in between, respectively (Figure 4A, Table 3). Among the 13 C1q− dnDSA patients at 2 years, none became C1q+ at 5 years, nine (69%) remained C1q−, and 3 (23%) no longer had dnDSAs. Among the 12 C1q+ dnDSA patients at 2 years, six (50%) remained C1q+ at 5 years while two (17%) became C1q−.

Figure 4.

Patients with C1q−/C1q+ dnDSAs at 1 or 2 and 5 years after transplantation. (A) Patients from the original Bordeaux Hospital cohort. (B and C) Patients from the external validation cohorts. Numbers at risk at the time of dnDSA detection are shown above the histogram bars. Patients with C1q− (white bars) and C1q+ (black bars) dnDSA detected at 2 or 5 years after transplantation (except in the Hospices Civils de Lyon Cohort: detection at 1 or 5 years). C1q− dnDSAs were considered persistent (gray bars) if detected at both 2 and 5 years after transplantation. There was no persistent C1q− dnDSA (i.e. detected both at 1 and 5 years after transplantation) in the Hospices Civils de Lyon cohort.

Table 3.

Evolution of dnDSAs 2–5 years after transplantation in the three cohorts

| Variable | DSAs Detected at 5 yr after Transplantation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No dnDSA | C1q− dnDSA | C1q+ dnDSA | Graft Loss/ Death/ Lost to Follow-up/ No Serum | |

| Bordeaux Hospital (n=346) | ||||

| DSAs detected at 2 yr after transplantation (n) | 286 | 22 | 8 | 30 |

| No dnDSA (n=321) | 283 (88) | 11 (3) | 2 (1) | 25 (8) |

| C1q− dnDSA (n=13) | 3 (23) | 9 (69) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| C1q+ dnDSA (n=12) | 0 | 2 (17) | 6 (50) | 4 (33) |

| Hospices Civils de Lyon (n=295) | ||||

| DSAs detected at 1 yr after transplantation (n) | 249 | 9 | 21 | 16 |

| No dnDSA (n=287) | 247 (86) | 9 (3) | 16 (6) | 15 (5) |

| C1q− dnDSA (n=2) | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 |

| C1q+ dnDSA (n=6) | 1 (17) | 0 | 4 (66) | 1 (17) |

| University of Manitoba (n=508) | ||||

| DSAs detected at 2 yr after transplantation (n) | 285 | 15 | 16 | 192 |

| No dnDSA (n=495) | 285 (58) | 8 (1.5) | 13 (2.5) | 189 (38) |

| C1q− dnDSA (n=10) | 0 | 6 (60) | 1 (10) | 3 (30) |

| C1q+ dnDSA (n=3) | 0 | 1 (33) | 2 (67) | 0 |

Unless otherwise noted, values are the number (percentage).

dnDSA at 2 and 5 Years after Transplantation and Graft Survival

Three patient groups were constituted to analyze the long-term effect of C1q+ and C1q− dnDSAs: patients without dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years (n=308), patients with only C1q− dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years (n=24), and patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years (n=14). The latter group included two patients with C1q+ then C1q− dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years, respectively (Table 3).

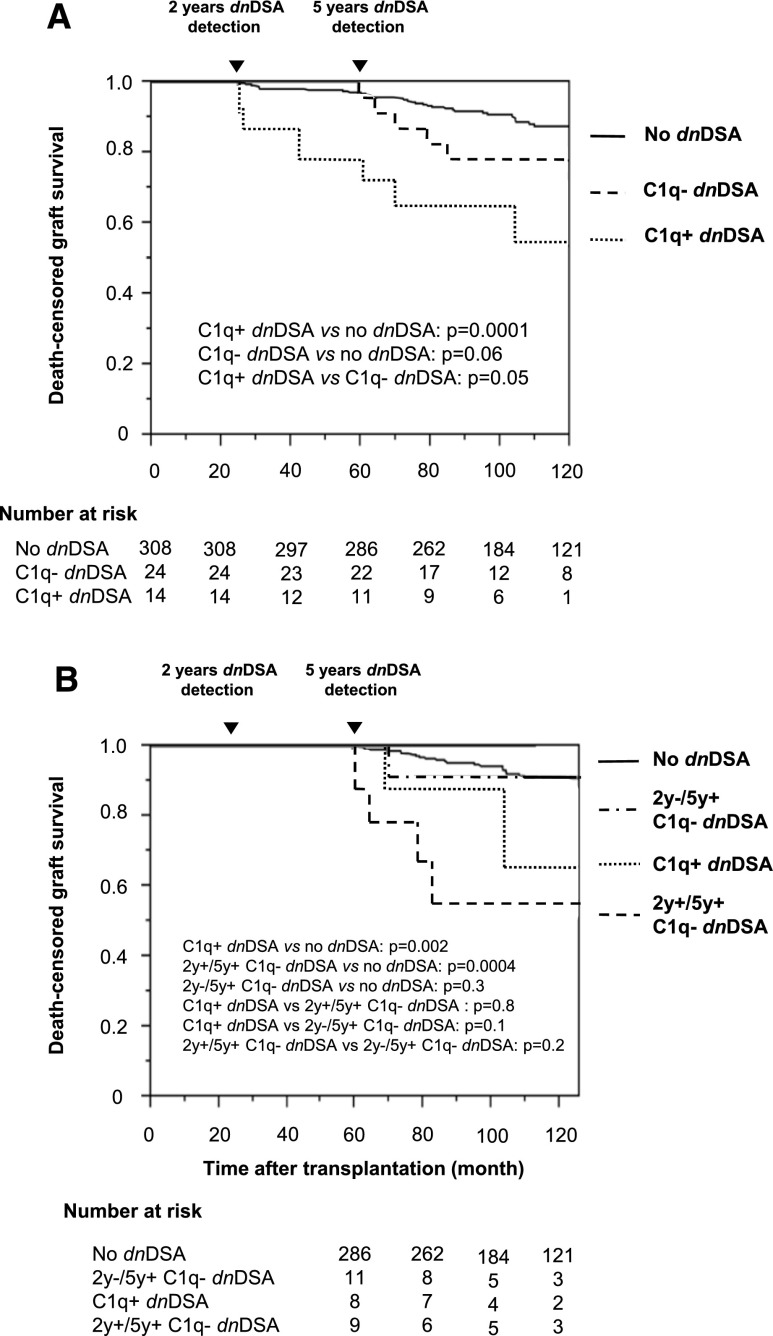

After 5 years, patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years still had a lower graft survival rate than C1q− dnDSA patients (P=0.05) (Figure 5A). However, long-term death-censored graft survival rate was lower in patients with C1q+ or C1q− dnDSAs than in those without dnDSAs. The difference in death-censored graft survival between patients with C1q− dnDSAs and those without dnDSAs appeared after 5 years, suggesting that prolonged exposure to C1q− dnDSAs also accelerated graft loss. The dnDSA number and dnDSA MFI sum were less efficient than C1q-binding ability for classifying the risk of graft loss (result not shown).

Figure 5.

Death-censored graft survival according to the presence of dnDSAs detected at 2 and 5 years after transplantation. (A) Patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years, with only C1q− dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years, and without dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years. (B) Patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years, C1q− dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years (2 years+/5 years+), no dnDSAs at 2 years, and C1q− dnDSAs at 5 years (2 years−/5 years+), and without dnDSA at 2 and 5 years.

dnDSA at 5 Years after Transplantation and Graft Survival

To analyze the long-term effect of C1q− dnDSAs, we compared the long-term death-censored graft survival rate between patients with C1q− dnDSAs at 5 years (n=22) and those with C1q+ dnDSAs (n=8) or no dnDSAs (n=286) at 5 years. We divided the C1q− dnDSA group into three subgroups: patients with no dnDSAs at 2 years and C1q− dnDSAs at 5 years (2 years−/5 years+ C1q− dnDSA; n=11), patients with C1q− dnDSAs at both 2 and 5 years (2 years+/5 years+ C1q− dnDSA; n=9), and patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 years and C1q− dnDSAs at 5 years (n=2). No graft loss occurred in the latter small group. Patients with 2 years−/5 years+ C1q− dnDSAs had the same graft survival rate as patients with no dnDSAs (P=0.3) (Figure 5B). In contrast, patients with 2 years+/5 years+ C1q− dnDSAs had a lower death-censored graft survival rate than those without dnDSAs (P<0.001) and had the same long-term outcome as patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 5 years (P=0.8). Twelve patients died after 5 years post-transplantation: Eleven had no dnDSAs and one had C1q− dnDSAs (P=0.9).

Histology of Graft Failure

Among the 51 patients who lost their graft during follow-up, 46 had a "for cause" graft biopsy (Table 4). Median time between transplantation and biopsy was similar between patients without dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years (n=34), patients with only C1q− dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years (n=5), and patients with C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years (n=7) (P=0.4). Mean Banff scores were similar between the groups. Chronic AMR was the leading cause of graft loss in patients with C1q− or C1q+ dnDSAs, whereas interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy and isolated transplant glomerulopathy predominated in the no-dnDSA group.

Table 4.

Histologic analysis of graft failure

| Variable | No dnDSAs (n=34) | C1q− dnDSAs (n=5) | C1q+ dnDSAs (n=7) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median time between transplant and biopsy (d) | 2032 (154–4115) | 2073 (1026–4471) | 1528 (373–3241) | 0.4 |

| Median time between biopsy and graft loss (d) | 319 (0–1747) | 49 (42–939) | 396 (248–841) | 0.4 |

| Banff scores | ||||

| i | 1.02±0.67 | 1.20±0.44 | 1.28±1.11 | 0.8 |

| t | 0.56±0.79 | 0.40±0.90 | 0.14±0.38 | 0.4 |

| g | 0.21±0.60 | 0.20±0.45 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.6 |

| ptc | 0.13±0.34 | 0.40±0.89 | 0.57±0.79 | 0.2 |

| v | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 1.0 |

| ci | 2.12±0.65 | 2.00±0.71 | 1.85±0.69 | 0.6 |

| ct | 2.06±0.66 | 2.20±0.84 | 1.71±0.76 | 0.4 |

| cv | 1.03±0.89 | 1.16±1.14 | 1.00±0.70 | 0.6 |

| cg | 0.94±1.22 | 1.40±1.14 | 1.71±1.11 | 0.2 |

| C4d>0, n (%) | 5 (23) | 1 (20) | 2 (29) | 0.5 |

| Banff diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic AMRa | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 6 (86) | 0.001 |

| Suspicious AMRb | 6 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy | 20 (59) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | |

| Transplant glomerulopathy | 8 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| AMR characteristics, n (%) | ||||

| C4d+ AMR | 1 (20) | 2 (33) | ||

| C4d− AMR | 4 (80) | 4 (67) |

Median values are expressed with minimum and maximum in parentheses. Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD.

Biopsies showing histologic evidence of chronic tissue injury (cg>0, cv>0) and dnDSA were considered as chronic AMR, even if evidence of current/recent antibody interaction with vascular endothelium (C4d>0 or g+ptc≥2) was absent.

Biopsies showing both histologic evidence of acute (g>0, ptc>0, v>0) or chronic (cg>0, cv>0) tissue injury and evidence of current/recent antibody interaction with vascular endothelium (C4d>0 or g+ptc≥2), but no dnDSA, were designated as suspicious AMR.

Risk Factors for dnDSA

Univariate analysis identified only HLA A-B-DR-DQ mismatches and HLA-DQ mismatches as risk factors for dnDSA appearance (A-B-DR-DQ: odds ratio, 1.30 [95% confidence interval, 1.01 to 1.68], P=0.04; DQ: odds ratio, 2.39 [95% confidence interval, 1.31 to 4.40], P=0.004, other data not shown).

Univariate then multivariate analyses also identified HLA A-B-DR-DQ mismatches, HLA-DQ mismatches, and cyclosporine-based immunosuppressive regimens as independent risk factors for C1q+ dnDSA appearance (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk factors for appearance of de novo C1q-binding DSA

| Variable | No C1q+ dnDSAs | C1q+ dnDSA | Odds Ratio Univariate Analysis (95% CI) | P Value | Odds Ratio Multivariate Analysis (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.06 | |||||

| Female | 92 (27.7) | 1 (7.1) | 1 | |||

| Male | 240 (72.3) | 13 (92.9) | 4.98 (0.97 to 91.12) | |||

| Recipient age (yr) | 47.5±12.6 | 41.4±14.4 | 0.12 (0.01 to 1.40) | 0.09 | ||

| Time on dialysis (mo) | 31.3±31.2 | 34.7±29.1 | 2.27 (0.01 to 73.62) | 0.7 | ||

| Extended-criteria donor | 0.5 | |||||

| No | 252 (78.7) | 10 (71.4) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 68 (21.3) | 4 (28.6) | 1.48 (0.39 to 4.58) | |||

| No. of HLA A-B-DR-DQ mismatches | 2.5±1.3 | 3.9±1.1 | 2.22 (1.45 to 3.59) | 0.0002 | 2.19 (1.37 to 3.72) | 0.001 |

| No. of HLA DQ mismatches | 0.5±0.5 | 1.1±0.6 | 6.14 (2.35 to 17.49) | 0.0002 | 4.08 (1.37 to 13.31) | 0.01 |

| Cold ischemia time (h) | 18.5±7.8 | 16.5±10.3 | 0.27 (0.01 to 3.85) | 0.4 | ||

| Induction | 0.9 | |||||

| No induction | 84 (25.3) | 3 (21.4) | 1 | |||

| Daclizumab | 203 (61.1) | 9 (64.3) | 1.24 (0.36 to 5.69) | |||

| Antithymocyte globulins | 45 (13.6) | 2 (14.3) | 1.24 (1.16 to 7.77) | |||

| Tacrolimus versus cyclosporine A at transplantation | 110 (33.3) | 1 (7.1) | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | |

| 217 (65.8) | 12 (85.7) | 6.08 (1.17 to 111.48) | 7.62 (1.34 to 145.20) | 0.02 | ||

| MMF versus azathioprine at transplantation | 299 (90.6) | 13 (92.8) | 1 | 0.8 | ||

| 29 (8.8) | 1 (7.1) | 0.79 (0.04 to 4.20) | ||||

| Delayed graft function | 0.4 | |||||

| No | 253 (76.7) | 12 (85.7) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 77 (23.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0.54 (0.08 to 2.06) | |||

| Tacrolimus versus cyclosporine A at 2 yr | 160 (48.6) | 4 (30.8) | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| 161 (48.9) | 8 (61.5) | 1.98 (0.61 to 7.56) | ||||

| MMF versus azathioprine at 2 yr | 284 (90.4) | 12 (85.7) | 1 | 0.6 | ||

| 30 (9.6) | 2 (14.3) | 1.57 (0.23 to 6.15) | ||||

| Steroid withdrawal at 2 yr | 0.5 | |||||

| No | 168 (51.8) | 6 (42.9) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 156 (48.2) | 8 (57.1) | 1.44 (0.48 to 4.44) | |||

| Borderline rejection before 2 yr | 0.2 | |||||

| No | 312 (94.0) | 14 (100) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 20 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 0.01 (0.00 to 2.40) | |||

| TCMR before 2 yr | 0.8 | |||||

| No | 291 (87.6) | 12 (85.7) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 41 (12.3) | 2 (14.3) | 1.18 (0.18 to 4.54) | |||

| Acute clinical AMR before 2 yr | 0.2 | |||||

| No | 328 (99%) | 13 (93%) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 4 (1%) | 1 (7%) | 6.30 (0.31 to 46.56) |

Unless otherwise noted, values are the number (percentage). Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD. MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; TCMR, T cell–mediated rejection; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

External Validation Cohorts

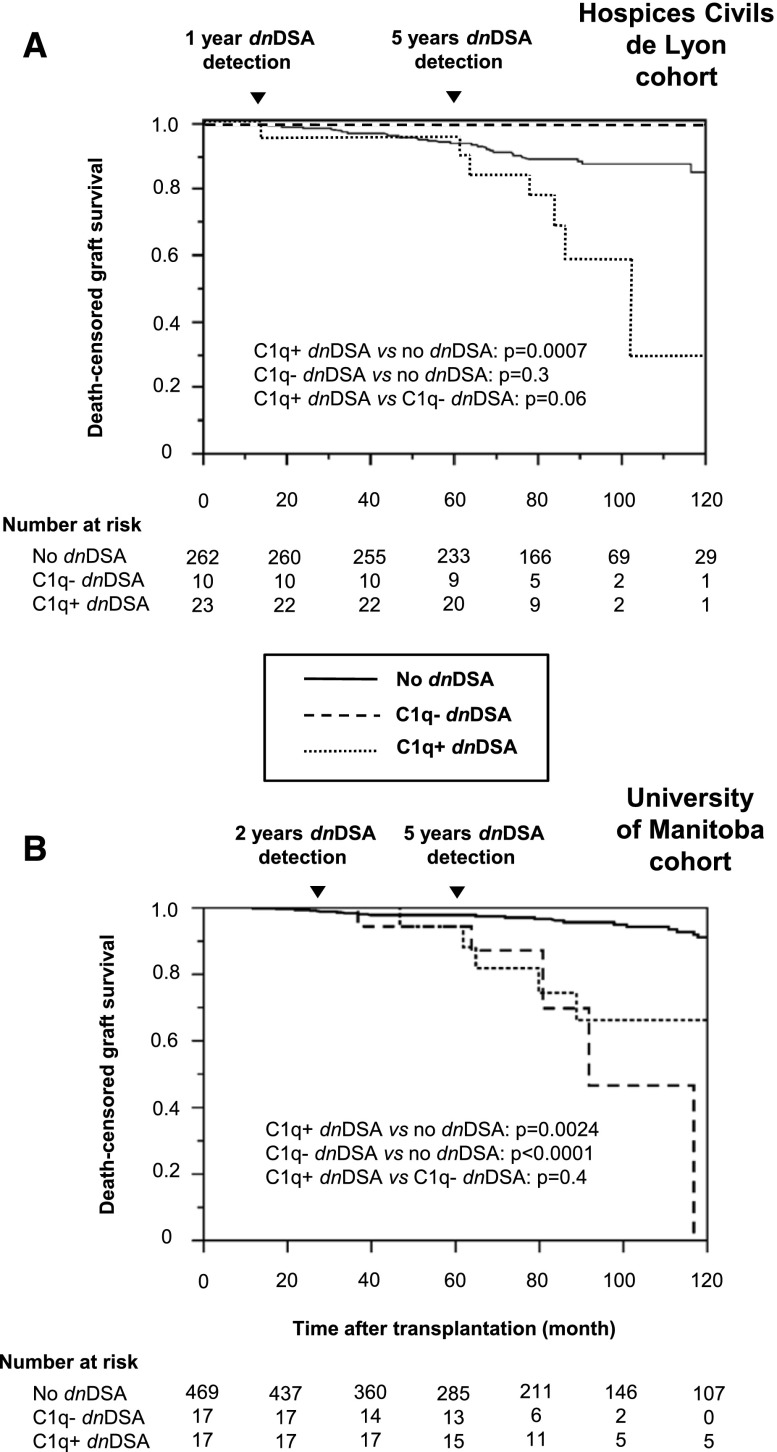

A first validation cohort originated from Hospices Civils de Lyon. Evolution of dnDSAs between 1 and 5 years is shown in Table 3 and Figure 4B. Because only two and six patients had C1q− and C1q+ dnDSAs at 1 year, respectively, analyzing the 5-year death-censored graft survival according to the 1-year C1q+/− dnDSA status was impossible. With most dnDSAs occurring at 5 years, we confirmed that shortly after the occurrence of C1q+ dnDSAs, death-censored graft survival rate was significantly lower than in patients with no dnDSAs or with only C1q− dnDSAs (Figure 6A). Death-censored graft survival rates in patients with C1q− dnDSAs were not lower than in patients with no dnDSAs, but no patient in this cohort had persistent C1q- dnDSAs at either 1 or 5 years.

Figure 6.

Death-censored graft survival according to the presence of C1q+/C1q− dnDSAs detected at 2 and/or 5 years post-transplantation in the two external validation cohorts. (A) Hospices Civils de Lyon. (B) University of Manitoba.

A second validation cohort originated from the University of Manitoba (Figure 4C, Table 3). Again, because only three patients presented C1q+ dnDSAs at 2 years, analyzing the 5-year death-censored graft survival rate according to the 2-year C1q+/− dnDSA status was impossible. This cohort confirmed that long-term death-censored graft survival rate was lower in patients with C1q+ or C1q− dnDSAs than in those without dnDSA (Figure 6B). Of note, graft losses in the C1q+ group were delayed compared with the original Bordeaux cohort, as was the occurrence of C1q+ dnDSA. Finally, because only six patients had C1q− dnDSAs at both 2 and 5 years, we could not confirm whether patients with persistent C1q− dnDSAs detected at both 2 and 5 years had a lower graft survival rate (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The association between dnDSA and lower graft survival rate reported in previous studies led to the proposal of introducing dnDSAs as an immunologic marker for post-transplant follow-up. The present study confirms that C1q+ dnDSA is a valuable tool associated with early graft loss but suggests that long-term exposure to C1q− dnDSA is similarly associated with graft failure.

In our study, the incidence of dnDSAs (7% at 2 years and 9% at 5 years after transplantation) was lower than previously reported,6,7 possibly because we performed antibody screening less frequently. However, the proportion of C1q+ dnDSAs was consistent with other studies.15,19 As previously described,15,17,18,21 we observed a correlation between DSA MFIs and their ability to bind C1q. We defined an MFI threshold that predicted C1q binding with very good sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values. Nevertheless, the value of this observation is hampered by weak correlation coefficients because some dnDSAs with high MFI do not bind complement. The latter scenario could be due to the IgG isotype or to changes in the glycosylation status of the Fc fragment.22 Low MFI DSAs were previously found to be C1q+,20 and this also occurred in four patients in our study. For these four patients, the explanation was a complement interference phenomenon due to the accumulation on the beads of activated C3 and C4, dose-dependently hindering the binding of the fluorescent anti-IgG conjugate to the serum HLA antibody.23 Chelating bivalent cations with EDTA to block complement activation restored the detection of anti-HLA antibodies.24,25 Therefore, in the absence of EDTA, the SAFB assay underestimated the MFI strength of these C1q+ dnDSAs in these four patients. This finding raises the hypothesis that the EDTA-treated SAFB assay could be better correlated with the C1q assay than the classic IgG SAFB assay. However, our study is insufficiently powered to answer this question. If this hypothesis is true, DSA detection with serum EDTA pretreatment may improve the accuracy of IgG SAFB testing to predict graft loss in the future.

We also noticed that class I dnDSAs had a lower MFI than did class IIs and were all C1q−. It is unknown whether class I dnDSAs do not bind C1q because they intrinsically cannot or because of an insufficient serum concentration reflected by a low SAFB MFI. Previous studies reporting both class I and class II C1q+ antibodies, either preformed or de novo,17,19–21 strongly support the latter hypothesis.

The major findings of the present study are related to the long-term follow-up of our patients. The availability of two sera at 2 and 5 years after transplantation for each patient allowed us to monitor the evolution of dnDSAs and compare graft survival according to the duration of exposure to C1q+ or C1q− dnDSAs. We first confirm the widely reported negative effect of dnDSAs on graft survival.6–9,20 We also confirm previous results showing a poorer medium-term graft survival in patients with C1q+ dnDSAs compared with those with no dnDSAs or C1q− dnDSAs.15,19,20 Of note, we also observed in the original cohort that patients with C1q− dnDSAs at 2 and 5 years had the same 10-year graft survival rates as those with C1q+ dnDSAs, whereas C1q− dnDSAs detected only at 2 or 5 years had no significant effect on graft survival. Thus, a long exposure (here for at least 3 years) to C1q− dnDSA could also be associated with graft loss. Using the Lyon validation cohort, we confirm that medium-term death-censored graft survival rate is lower in patients developing C1q+ dnDSAs than in patients without dnDSAs or with C1q− dnDSAs. Using the Manitoba validation cohort, we confirm that after 5 years, both patients with C1q+ or C1q− dnDSAs at 2 or 5 years have a lower graft survival than those without dnDSAs. However, none of these two cohorts contained enough patients with C1q− dnDSAs at both 2 and 5 years to confirm definitively that long-term exposure to C1q− dnDSAs is also associated with graft failure.

From a mechanistic point of view, this difference in effect over time between C1q+ and C1q− dnDSAs suggests that two processes underlie chronic antibody-mediated graft injuries and graft loss initiated by DSA deposition.26 On the one hand, as C1q is the complement classic pathway’s first protagonist, the ability of DSA to bind C1q in vitro should determine its ability to activate the complement cascade in vivo,27 before membrane attack complex formation and subsequent lysis of renal endothelial cells, which lead relatively quickly to graft loss. On the other hand, C1q− dnDSAs could cause long-term graft loss independently of complement activation by inducing persistent microcirculation inflammation and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity,28,29 or by direct activation of endothelial cell survival and proliferation.30

The association between complement-binding ability and time to graft loss in patients with DSA could also have a therapeutic effect. The anti-C5 antibody eculizumab is a promising tool that inhibits complement membrane-attack complex formation and reduces early clinical AMR.31 Our findings suggest that DSA+ patients treated with eculizumab could have a better medium-term, but not long-term, graft survival.

We were unable to confirm whether more acute clinical AMR occurs in patients with C1q+ dnDSAs.7,12 This could be due to the absence in our center of early protocol graft biopsies, which usually show subclinical AMR in patients with preformed DSA.32,33 Loupy et al. reported that patients with C1q+ DSAs had more microcirculation inflammation and C4d deposition than those with C1q− DSAs or no DSAs in 1-year protocol biopsies. This association could fade over time because our late biopsies exhibited a high incidence of interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and transplant glomerulopathy, without any difference in microcirculation inflammation or C4d deposition between patients with C1q+, C1q−, or no dnDSAs. Nevertheless, we found that AMR was the leading cause of graft loss both in patients with C1q− and C1q+ dnDSAs, whereas mostly interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy and isolated transplant glomerulopathy were found in the last biopsy before graft loss in patients without dnDSA. These results are in line with the negative effect of both C1q− and C1q+ dnDSAs on graft outcome.

Finally, we found two independent risk factors for C1q+ dnDSA appearance. The first was the number of HLA A-B-DR-DQ mismatches (and the number of DQ mismatches alone), which is widely recognized as a risk factor for dnDSA appearance.6,8–10 The second is the cyclosporine A (versus tacrolimus)-based immunosuppressive regimen started at the time of transplantation. Our results thus suggest that tacrolimus could more strongly inhibit the humoral alloresponse. This could partly explain the better efficacy observed with tacrolimus after kidney transplantation in some previous reports.34,35 Other items classically associated with sensitization may be lacking in our analysis, but blood transfusions are not associated with the appearance of dnDSAs,36 nonadherence is difficult to measure reliably,37 and no post-transplantation pregnancy occurred during the follow-up.

In conclusion, this 10-year follow-up study shows that both C1q+ and C1q− dnDSAs are associated with graft loss and that a longer exposure to C1q− than to C1q+ dnDSAs is possibly needed to induce graft failure.

CONCISE METHODS

Patients

The 370 consecutive nonsensitized patients who received a deceased-donor kidney allograft at Bordeaux University Hospital from January 1998 to December 2005 were eligible for this retrospective study. Because dnDSAs were retrospectively screened at 2 and 5 years after transplantation, we excluded the 16 recipients who died with a functioning graft or lost their graft before 2 years, as well as the three patients without serum collected at 2 and 5 years (Figure 1). Demographic data, immunosuppressive regimens, biopsy-proven acute rejection, serum creatinine, patient and graft survival, and other clinical data were obtained from our electronic medical database. Patients were followed until June 2012. The local institutional review board approved the study, and each patient provided informed consent.

Two external validation cohorts originated from the Hospices Civils de Lyon, Hôpital Edouard Herriot (Lyon, France), and University of Manitoba (Winnipeg, Canada). The 295 patients from the Hospices Civils de Lyon underwent transplantation between 2000 and 2009. Their characteristics are shown in Supplemental Table 2. Sera were available at 1 (instead of 2) and 5 years after transplantation. The characteristics of the 508 patients from the Canadian cohort have been previously reported.9 Sera were available at 2 and 5 years after transplantation.

Anti-HLA Antibody Screening

For the Bordeaux cohort, serum samples obtained before and 2 and 5 years after transplantation were screened for HLA class I and II antibodies using the LABScreen Mixed flow beads assay (ref LSM12; One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA). We excluded another five recipients who had preformed anti-HLA antibodies retrospectively detected by Luminex on the pretransplant sera (Figure 1) because until April 2005 the routine detection of anti-HLA antibodies relied on a slightly less sensitive ELISA (One Lambda). When the result of the post-transplant screening assay was positive, antibody specificities were determined using the class I and/or II SAFB assays (ref LS1A04 and LS2A01, respectively; One Lambda). Tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For the SAFB assays, the MFI results were normalized using the baseline formula proposed by the HLA Fusion 2.0 software (One Lambda), as described previously.38 The threshold for positivity was set at a baseline MFI value of 500. DSA antigenic targets were identified by comparing the donor-recipient mismatched HLA to the antibody profile for each patient's sample. DNA typing of the C (LabType SSO; One Lambda) and DPB1 (Olerup SSP-PCR; Bionobis, Guyancourt, France) loci was additionally performed for donors and recipients when the recipient was sensitized against Cw or DP antigens.

For the external validation cohorts, pre- and post-transplant sera were first analyzed using flow bead screening assays. For the positive post-transplant sera, antibody specificities were determined using the class I and/or II SAFB assays (One Lambda and Immucor [Norcross, GA] for the Manitoba and Lyon validation cohorts, respectively).

C1q-Binding Assay

For the Bordeaux cohort, sera containing dnDSAs underwent further testing using a C1q SAFB assay with a protocol slightly modified from Lachmann et al.18 After heat inactivation at 56°C for 30 minutes and centrifugation, serum (18 µl) was spiked with 4 µl of human C1q (4 µg; Quidel, San Diego, CA) and incubated with 2 µl class I or class II SAFB for 20 minutes at room temperature. A biotinylated monoclonal anti-human C1q antibody (clone 3R9/2, Quidel) was added (30 µl of a 1:30 dilution) and incubated for 20 minutes. Beads were washed twice with the washing buffer from the SAFB kit and resuspended in 100 µl PE-conjugated polyclonal anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Beckman-Coulter, San Jose, CA) for a 20-minute incubation period. Beads were washed twice and resuspended in 80 µl PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, South Logan, UT). Data were acquired using a Luminex 100 analyzer.

For the external validation cohorts, the C1q-binding ability of dnDSAs was analyzed with the SAFB assay (C1qScreen; One Lambda) performed at the University of Manitoba for the Canadian cohort and at Bordeaux University Hospital for the Lyon cohort.

Serum Preincubation with EDTA to Investigate a Complement Interference Phenomenon

Sera containing C1q+ dnDSA, which had an MFI in SAFB assay below the threshold predicting C1q binding, were retested with the SAFB assay after preincubation with EDTA to disrupt C1, as previously reported.23,24

Graft Outcome

The eGFR was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula at 1, 2, and 5 years after transplantation. "For cause" allograft biopsies were performed when serum creatinine rose by more than 20% compared with previous measurements or when increased levels of proteinuria were detected. Protocol biopsies were not performed in our center. The last biopsy specimen available before graft loss was retrospectively analyzed by the same pathologist according to the most recent Banff classification.39,40 All acute rejections were biopsy proven and classified in the same manner. Graft loss was defined as return to dialysis.

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons between the groups were performed using conventional statistics for matched data: the McNemar chi-squared or Fisher test for qualitative variables, t test, or Wilcoxon rank-test were used when appropriate. Graft survival and patient survival were analyzed with the Kaplan–Meier method, and group differences were assessed by the log-rank test. The variables potentially associated with the occurrence of dnDSAs or C1q+ dnDSAs were subjected to univariate analysis. Risk factors with P<0.05 were included in a multivariate model. Analyses were performed with JMP.10, version 2012 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Rio for her help as a nurse coordinator in Bordeaux and Daniel Sperandio, Fathia M'Raiagh, and Aurélien Meunier for their help in collecting clinical and immunologic data from the Hospices Civils de Lyon.

This study was funded by Bordeaux University Hospital (AOI 2008) and the Fédération Nationale d'Aide aux Insuffisants Rénaux d’Aquitaine.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014040326/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Einecke G, Sis B, Reeve J, Mengel M, Campbell PM, Hidalgo LG, Kaplan B, Halloran PF: Antibody-mediated microcirculation injury is the major cause of late kidney transplant failure. Am J Transplant 9: 2520–2531, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaston RS, Cecka JM, Kasiske BL, Fieberg AM, Leduc R, Cosio FC, Gourishankar S, Grande J, Halloran P, Hunsicker L, Mannon R, Rush D, Matas AJ: Evidence for antibody-mediated injury as a major determinant of late kidney allograft failure. Transplantation 90: 68–74, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, Reeve J, Einecke G, Sis B, Hidalgo LG, Famulski K, Matas A, Halloran PF: Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: The dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant 12: 388–399, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Hill GS, Andrade J, Nochy D, Antoine C, Gautreau C, Charron D, Glotz D, Suberbielle-Boissel C: Preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies predict outcome in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1398–1406, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloor JM, Winters JL, Cornell LD, Fix LA, DeGoey SR, Knauer RM, Cosio FG, Gandhi MJ, Kremers W, Stegall MD: Baseline donor-specific antibody levels and outcomes in positive crossmatch kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 10: 582–589, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ntokou I-SA, Iniotaki AG, Kontou EN, Darema MN, Apostolaki MD, Kostakis AG, Boletis JN: Long-term follow up for anti-HLA donor specific antibodies postrenal transplantation: High immunogenicity of HLA class II graft molecules. Transpl Int 24: 1084–1093, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper JE, Gralla J, Cagle L, Goldberg R, Chan L, Wiseman AC: Inferior kidney allograft outcomes in patients with de novo donor-specific antibodies are due to acute rejection episodes. Transplantation 91: 1103–1109, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everly MJ, Rebellato LM, Haisch CE, Ozawa M, Parker K, Briley KP, Catrou PG, Bolin P, Kendrick WT, Kendrick SA, Harland RC, Terasaki PI: Incidence and impact of de novo donor-specific alloantibody in primary renal allografts. Transplantation 95: 410–417, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiebe C, Gibson IWI, Blydt-Hansen TDT, Karpinski M, Ho J, Storsley LJL, Goldberg A, Birk PEP, Rush DND, Nickerson PWP: Evolution and clinical pathologic correlations of de novo donor-specific HLA antibody post kidney transplant. Am J Transplant 12: 1157–1167, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liefeldt L, Brakemeier S, Glander P, Waiser J, Lachmann N, Schönemann C, Zukunft B, Illigens P, Schmidt D, Wu K, Rudolph B, Neumayer HH, Budde K: Donor-specific HLA antibodies in a cohort comparing everolimus with cyclosporine after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 12: 1192–1198, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Kort H, Willicombe M, Brookes P, Dominy KM, Santos-Nunez E, Galliford JW, Chan K, Taube D, McLean AG, Cook HT, Roufosse C: Microcirculation inflammation associates with outcome in renal transplant patients with de novo donor-specific antibodies. Am J Transplant 13: 485–492, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caro-Oleas JL, González-Escribano MF, Gentil-Govantes MÁ, Acevedo MJ, González-Roncero FM, Blanco GB, Núñez-Roldán A: Clinical relevance of anti-HLA donor-specific antibodies detected by Luminex assay in the development of rejection after renal transplantation. Transplantation 94: 338–344, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartel G, Regele H, Wahrmann M, Huttary N, Exner M, Hörl WH, Böhmig GA: Posttransplant HLA alloreactivity in stable kidney transplant recipients-incidences and impact on long-term allograft outcomes. Am J Transplant 8: 2652–2660, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizutani K, Terasaki P, Hamdani E, Esquenazi V, Rosen A, Miller J, Ozawa M: The importance of anti-HLA-specific antibody strength in monitoring kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant 7: 1027–1031, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freitas MCS, Rebellato LM, Ozawa M, Nguyen A, Sasaki N, Everly M, Briley KP, Haisch CE, Bolin P, Parker K, Kendrick WT, Kendrick SA, Harland RC, Terasaki PI: The role of immunoglobulin-G subclasses and C1q in de novo HLA-DQ donor-specific antibody kidney transplantation outcomes. Transplantation 95: 1113–1119, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hönger G, Hopfer H, Arnold M-L, Spriewald BM, Schaub S, Amico P: Pretransplant IgG subclasses of donor-specific human leukocyte antigen antibodies and development of antibody-mediated rejection. Transplantation 92: 41–47, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen G, Sequeira F, Tyan DB: Novel C1q assay reveals a clinically relevant subset of human leukocyte antigen antibodies independent of immunoglobulin G strength on single antigen beads. Hum Immunol 72: 849–858, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lachmann N, Todorova K, Schulze H, Schönemann C: Systematic comparison of four cell- and Luminex-based methods for assessment of complement-activating HLA antibodies. Transplantation 95: 694–700, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yabu JM, Higgins JP, Chen G, Sequeira F, Busque S, Tyan DB: C1q-fixing human leukocyte antigen antibodies are specific for predicting transplant glomerulopathy and late graft failure after kidney transplantation. Transplantation 91: 342–347, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loupy A, Lefaucheur C, Vernerey D, Prugger C, Duong van Huyen JP, Mooney N, Suberbielle C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Méjean A, Desgrandchamps F, Anglicheau D, Nochy D, Charron D, Empana J-P, Delahousse M, Legendre C, Glotz D, Hill GS, Zeevi A, Jouven X: Complement-binding anti-HLA antibodies and kidney-allograft survival. N Engl J Med 369: 1215–1226, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otten HG, Verhaar MC, Borst HPE, Hené RJ, van Zuilen AD: Pretransplant donor-specific HLA class-I and -II antibodies are associated with an increased risk for kidney graft failure. Am J Transplant 12: 1618–1623, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anthony RM, Nimmerjahn F: The role of differential IgG glycosylation in the interaction of antibodies with FcγRs in vivo. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 16: 7–14, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Visentin J, Vigata M, Daburon S, Contin-Bordes C, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Dromer C, Billes M-A, Neau-Cransac M, Guidicelli G, Taupin J-L: Deciphering complement interference in anti-human leukocyte antigen antibody detection with flow beads assays. Transplantation 98: 625–631, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnaidt M, Weinstock C, Jurisic M, Schmid-Horch B, Ender A, Wernet D: HLA antibody specification using single-antigen beads—a technical solution for the prozone effect. Transplantation 92: 510–515, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guidicelli G, Anies G, Bachelet T, Dubois V, Moreau J-F, Merville P, Couzi L, Taupin J-L: The complement interference phenomenon as a cause for sharp fluctuations of serum anti-HLA antibody strength in kidney transplant patients. Transpl Immunol 29: 17–21, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stegall MD, Chedid MF, Cornell LD: The role of complement in antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 670–678, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Friec G, Kemper C: Complement: Coming full circle. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 57: 393–407, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirohashi T, Chase CM, Della Pelle P, Sebastian D, Alessandrini A, Madsen JC, Russell PS, Colvin RB: A novel pathway of chronic allograft rejection mediated by NK cells and alloantibody. Am J Transplant 12: 313–321, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hidalgo LG, Sis B, Sellares J, Campbell PM, Mengel M, Einecke G, Chang J, Halloran PF: NK cell transcripts and NK cells in kidney biopsies from patients with donor-specific antibodies: Evidence for NK cell involvement in antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 10: 1812–1822, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Reed EF: Effect of antibodies on endothelium. Am J Transplant 9: 2459–2465, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stegall MD, Diwan T, Raghavaiah S, Cornell LD, Burns J, Dean PG, Cosio FG, Gandhi MJ, Kremers W, Gloor JM: Terminal complement inhibition decreases antibody-mediated rejection in sensitized renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 11: 2405–2413, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haas M, Montgomery RA, Segev DL, Rahman MH, Racusen LC, Bagnasco SM, Simpkins CE, Warren DS, Lepley D, Zachary AA, Kraus ES: Subclinical acute antibody-mediated rejection in positive crossmatch renal allografts. Am J Transplant 7: 576–585, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loupy A, Suberbielle-Boissel C, Hill GS, Lefaucheur C, Anglicheau D, Zuber J, Martinez F, Thervet E, Méjean A, Charron D, Duong van Huyen JP, Bruneval P, Legendre C, Nochy D: Outcome of subclinical antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplant recipients with preformed donor-specific antibodies. Am J Transplant 9: 2561–2570, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster AC, Woodroffe RC, Taylor RS, Chapman JR, Craig JC: Tacrolimus versus ciclosporin as primary immunosuppression for kidney transplant recipients: Meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomised trial data. BMJ 331: 810, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, Vítko S, Nashan B, Gürkan A, Margreiter R, Hugo C, Grinyó JM, Frei U, Vanrenterghem Y, Daloze P, Halloran PF, ELITE-Symphony Study : Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 357: 2562–2575, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scornik JC, Guerra G, Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Dragun D, Meier-Kriesche HU: Value of posttransplant antibody tests in the evaluation of patients with renal graft dysfunction. Am J Transplant 7: 1808–1814, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fine RN, Becker Y, De Geest S, Eisen H, Ettenger R, Evans R, Rudow DL, McKay D, Neu A, Nevins T, Reyes J, Wray J, Dobbels F: Nonadherence consensus conference summary report. Am J Transplant 9: 35–41, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couzi L, Araujo C, Guidicelli G, Bachelet T, Moreau K, Morel D, Robert G, Wallerand H, Moreau J-F, Taupin J-L, Merville P: Interpretation of positive flow cytometric crossmatch in the era of the single-antigen bead assay. Transplantation 91: 527–535, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sis B, Mengel M, Haas M, Colvin RB, Halloran PF, Racusen LC, Solez K, Baldwin WM, 3rd, Bracamonte ER, Broecker V, Cosio F, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg C, Einecke G, Gloor J, Glotz D, Kraus E, Legendre C, Liapis H, Mannon RB, Nankivell BJ, Nickeleit V, Papadimitriou JC, Randhawa P, Regele H, Renaudin K, Rodriguez ER, Seron D, Seshan S, Suthanthiran M, Wasowska BA, Zachary A, Zeevi A: Banff ’09 meeting report: Antibody mediated graft deterioration and implementation of Banff working groups. Am J Transplant 10: 464–471, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas M, Sis B, Racusen LC, Solez K, Glotz D, Colvin RB, Castro MCR, David DSR, David-Neto E, Bagnasco SM, Cendales LC, Cornell LD, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Farver CF, Farris AB, 3rd, Gibson IW, Kraus E, Liapis H, Loupy A, Nickeleit V, Randhawa P, Rodriguez ER, Rush D, Smith RN, Tan CD, Wallace WD, Mengel M, Banff meeting report writing committee : Banff 2013 meeting report: Inclusion of c4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection and antibody-associated arterial lesions. Am J Transplant 14: 272–283, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.