Abstract

Microglia are resident macrophages of the CNS that are essential for phagocytosis of apoptotic neurons and weak synapses during development. We show that RagA and Lamtor4, two components of the Rag-Ragulator complex, are essential regulators of lysosomes in microglia. In zebrafish lacking RagA function, microglia exhibit an expanded lysosomal compartment but are unable to properly digest apoptotic neuronal debris. Previous biochemical studies have placed the Rag-Ragulator complex upstream of mTORC1 activation in response to cellular nutrient availability. Nonetheless, RagA and mTOR mutant zebrafish have distinct phenotypes, indicating that the Rag-Ragulator complex has functions independent of mTOR signaling. Our analysis reveals an essential role of the Rag-Ragulator complex in proper lysosome function and phagocytic flux in microglia.

Introduction

Maintenance of homeostasis in the central nervous system (CNS) is a critical challenge that metazoans face during development and disease. During development, some neurons have to be eliminated through apoptosis and cleared, while maintaining the health of neighboring neurons. Similarly, pruning of weak synapses is essential to remove inappropriate connections between neurons. A different challenge arises after infection, injury, or the onset of neurodegenerative disease, when clearance of pathogens and debris must occur while maintaining the integrity of surrounding healthy cells.

Microglia are specialized phagocytic cells that monitor the health of the CNS and maintain homeostasis. They are involved in debris and pathogen clearance, synapse remodeling and other processes in the CNS (Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008, Schafer et al., 2012). Microglia are highly dynamic cells that exhibit different responses to various perturbations in the CNS, for example by promoting healing after injury or by triggering an immune response after infection (Ransohoff and Perry, 2009). Microglia are also implicated in numerous CNS pathologies (Ransohoff and El Khoury, 2015). First, impaired microglial function may disrupt maintenance of homeostasis, thus causing or contributing to disease (Zhan et al., 2014). Second, microglia may promote inflammation that causes or exacerbates pathology in response to stimuli such as Aβ protein in Alzheimer disease or an infectious agent (Heppner et al., 2015 and Aguzzi et al., 2013). Increased understanding of microglial biology and function will elucidate their many roles in health and disease, and suggest how these activities may be harnessed therapeutically. It may be possible to manipulate microglia for therapeutic purposes, for example by enhancing phagocytosis to increase the clearance of Aβ protein in Alzheimer disease (Demattos et al., 2012). Despite the interest in microglia in CNS homeostasis, disease, and possible therapies, much remains unknown about the mechanisms that govern the phagocytic activity of microglia. Phagocytosis is the process in which a cell engulfs and degrades a particle. Phagocytosis is often described in the context of immune defense, and in some cells it is also involved in nutrient acquisition (Flannagan et al., 2012). The phagocytic cell entraps the particle in an intracellular vesicle called the phagosome. Fusion of the phagosome with an acidic lysosome forms the phagolysosome and allows lysosomal digestive enzymes to degrade the particle (Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008). Autophagy is a related process in which organelles and other cellular constituents are recycled via fusion of an autophagosome with a lysosome (Mizushima et al., 2008). In addition to their essential roles in the degradative processes of phagocytosis and autophagy, lysosomes are also central to a wide range of cellular activities such as plasma membrane repair (Reddy et al., 2015), cholesterol homeostasis (Lange et al., 1998), and apoptosis (Ivanova et al., 2008). Lysosomes are therefore crucial regulators of cellular homeostasis, and their dysfunction has been implicated in diseases including lysosome storage disorders (Platt et al., 2012) and neurodegenerative diseases (Zhang, 2009 and Ballabio and Giselmann, 2009).

Recent evidence also points to lysosomes as an assembly point for regulators of diverse cellular processes and pathways (Settembre et al., 2013). For example, mTORC1 is a master regulator that couples multiple cues such as nutrient availability and growth factor levels to cell growth (Laplante and Sabatini, 2015). High levels of lysosomal amino acids and other stimuli recruit mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface, where it is activated by Rheb (Long et al., 2005). The Rag-Ragulator complex is central to the recruitment and activation of mTORC1 at the lysosome (Sancak et al, 2010). Rag proteins are GTPases that function as heterodimers of either RagA or RagB with either RagC or Rag D (Sekiguchi et al., 2001). The Ragulator is a recently-discovered complex that functions as a scaffold for tethering Rag GTPases to the lysosome, as well as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that promotes Rag activity (Bar-Peled et al., 2012). The Rag-Ragulator complex thus links cellular nutrient levels to mTORC1 activation on the lysosomal surface.

Despite strong evidence that Rag-Ragulator activity is connected to the mTORC1 pathway, in vivo experiments have shown that mTORC1 can be activated in MEFs extracted from RagA knockout mice (Efeyan et al., 2014), as well as cardiomyocytes lacking both RagA and RagB (Kim et al., 2014). These studies provide evidence that mTORC1 can be active in the absence of the Rag function, but the mechanisms and prevalence of Rag-independent activation of mTORC1 is unclear. Recent evidence also suggests that Rag GTPases have functions that are independent of mTOR signaling: cardiomyocytes lacking RagA and RagB have defects in lysosomal function and acidification while retaining normal mTORC1 activity (Kim et al., 2014). It is not known whether the mTOR-independent functions of Rag signaling involve the Ragulator complex, and it is unclear how widespread these functions might be.

Through a forward genetic screen for microglia mutants, we identified rraga and lamtor4, which encodes a protein in the Ragulator complex, as genes essential for microglia development. In rraga mutants, microglia numbers are reduced, and those remaining exhibit an expanded lysosomal compartment. Despite the expansion of lysosomal organelles, microglia in rraga mutants are unable to digest neuronal debris. Furthermore, we show that the defects in rraga mutants are distinct from the defects in mtor mutants and that mTORC1 is active in rraga mutants. Our results indicate that the Rag-Ragulator complex acts independently of mTOR to regulate lysosomal activity in microglia.

Results

The Rag-Ragulator Complex is Required for Microglia Development

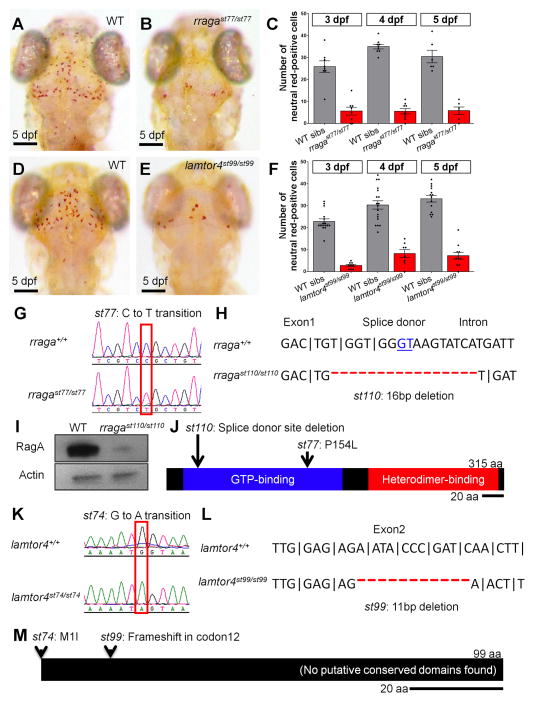

Starting with two parallel genetic screens for mutants with abnormalities in myelinating glia and microglia, we identified st77 and st74 as mutations that produce similar phenotypes in the CNS, including a reduction in the number of neutral red-stained microglia (Fig. 1A–C; Supp. Fig. 1E, F). Neutral red is a vital dye that accumulates in the lysosomes of microglia in living zebrafish larvae (Herbomel et al., 2001), and neutral red staining has been used to identify zebrafish mutants with abnormal microglia in our laboratory and others (e.g. Shiau et al. 2013; Rossi et al. 2015). Genetic mapping revealed that st77 and st74 define two different genes on chromosomes 14 and 4, respectively. High-resolution mapping and positional cloning identified the mutated genes as rraga and lamtor4, which encode RagA and Lamtor4, components of the Rag-Ragulator complex (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Mutational analysis demonstrates that rraga and lamtor4 are essential for microglia development.

(A–F) Comparison of microglia numbers in rragast77/st77 mutants, lamtor4st99/st99 mutants, and wildtype siblings. (A, B, D, E) Neutral red stained larvae of the indicated genotypes at 5 dpf. Dorsal views, scale bar = 50 μm. (C, F) Quantification of neutral red stained microglia in rraga (C) and lamtor4 (F) mutants at 3 dpf, 4 dpf and 5 dpf. (G–J) Molecular analysis of mutations in rraga. (G) Sequence chromatograms show point mutation in rragast77 mutation. (H) Sequence deleted in rragast110 mutation, showing exon-intron boundary and deleted splice donor. (I) Immunoblot showing pronounced reduction of RagA protein in rragast77/st77 mutants at 5 dpf. Actin is shown as a loading control. (J) Schematic of RagA protein, showing conserved domains and positions of the mutant lesions. (K–M) Molecular analysis of mutations in lamtor4. (K) Sequence chromatograms show point mutation in lamtor4st74 mutation, which changes the ATG initiation codon to ATA. (L) Sequence deleted in lamtor4st99 mutation, showing the reading frame in wildtype and the alteration caused by the 11 bp deletion in the mutation. (M) Schematic of the Lamtor4 protein, showing positions of the mutant lesions. Larvae shown in A, B, D, and E were genotyped by PCR after photography.

The st77 allele introduces a C to T transition in rraga (Fig. 1G, J), which changes a conserved proline residue to a leucine in the RagA protein. To confirm that rraga is the disrupted gene, we used TALE nucleases to generate st110, a 16 bp deletion at the exon1-intron1 boundary of rraga (Fig. 1H, J). There is a similar reduction in neutral red-stained microglia in rragast110/st110 and rragast77/st110 mutants (Supp. Fig. 1A–D), indicating that both mutations cause a loss of rraga function and that they fail to complement. Immunoblots showed that RagA protein levels are greatly reduced in rragast110/st110 mutants (Fig. 1I); a small amount of RagA was detected, likely due to maternal contribution (see Supp. Fig. 2A). These results demonstrate that the rraga gene is essential for microglia development.

Mapping and sequencing studies showed that the st74 allele introduces a G to A transition in the first codon of lamtor4, abolishing the translational initiation codon (Fig. 1K, M). To confirm that lamtor4 is the disrupted gene, we used TALE nucleases to create an additional mutation, st99, which is an 11 bp deletion predicted to eliminate lamtor4 function (Fig. 1L, M). There is a similar reduction in neutral red-stained microglia in lamtor4st99/st99 and lamtor4st74/st99 (Fig. 1D–F; Supp. Fig. 1E–H), indicating that both mutations cause a loss of lamtor4 function and that they fail to complement.

Thus our mutational analysis indicates that RagA and Lamtor4, a component of the Rag-associated Ragulator complex, are both essential for microglia development.

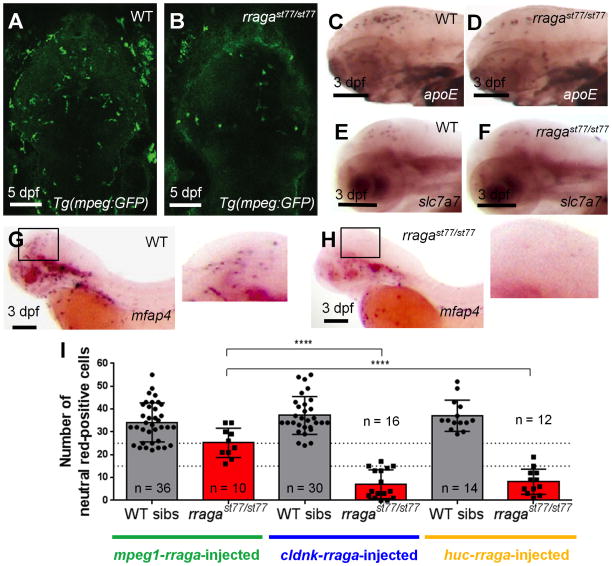

RagA is Autonomously Required in Microglia

To investigate the cellular basis of Rag-Ragulator action in microglial development, we examined the stage and cell-autonomy of rraga function. In zebrafish, microglia begin to differentiate at approximately 2.5 days post fertilization (dpf) from primitive macrophages that have entered the brain at earlier stages (Herbomel et al., 2001). At 3 dpf and continuing through 5 dpf, the number of neutral red positive cells was reduced in both rragast77/st77 and lamtor4st99/st99 mutants (Fig. 1A–F). At 5 dpf, the number of microglia assayed by neutral red staining ranged from 25–45 in wildtype siblings, and 0–15 in rragast77/st77 and lamtor4st99/st99 mutants (Fig. 1C, F). In addition, we examined other markers of microglia, including the mpeg1:EGFP transgenic reporter (Fig. 2A, B); apoe, which is a specific marker of microglia in zebrafish (Fig. 2C, D); and slc7a7, which defines a restricted sub-population of macrophages and is necessary for microglia formation (Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008, Ellett et al., 2011, Rossi et al., 2015) (Fig. 2E, F). These markers all revealed a reduction in microglial numbers in rragast77/st77 mutants. In addition, the markers showed that some of the microglia remaining in the mutants had an abnormal morphology that contrasts with the process-bearing microglia in wildtype (e.g., Fig. 1B, 1D, 2B). There were also fewer cells expressing the macrophage marker mfap4 (Zakrzewska et al., 2010) in the brains of rragast77/st77 mutants at 3 dpf (Fig 2G, H). These data show that rraga is essential for an early step in microglia development. In the mutants, microglia are reduced in number but not completely absent, and the remaining microglia have abnormal morphology.

Figure 2. rraga acts autonomously at an early stage of microglia development.

(A–B) Reduction of microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants detected by imaging the mpeg1:EGFP transgene in living wildtype (A) and mutant (B) larvae at 5dpf. Dorsal views, anterior to the top. (C–H) Analysis of other microglia and macrophage markers reveals reduction of microglia at 3 dpf. Probes for apoe (C, D), slc7a7 (E, F), and mfap4 (G, H) were detected by whole mount in situ hybridization. Boxes in G and H show region magnified in the corresponding insets. Lateral views, anterior to the left. (I) Quantification of neutral red stained microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants after transient expression of the wildtype rraga coding sequence under control of regulatory sequences from mpeg1, cldnk, and huc. Only mpeg1-rraga, which drives expression in macrophages and microglia, significantly rescued microglia in the mutants. Dotted line at 15 and 25 shows weak and strong rescue, respectively. ****, P ≤ 0.0001. All scale bars are 50μm. All larvae shown were genotyped by PCR after photography (A–H) or after visually scoring neutral red phenotypes (I).

In situ hybridization indicated that rraga is widely expressed (Supp. Fig. 2B) and maternally provided (Supp. Fig. 2A), so we adopted a cell-type specific expression approach to assess the cell autonomy of rraga function. We expressed the wildtype rraga coding sequence in macrophages/microglia, oligodendrocytes, or neurons using regulatory sequences from mpeg1, claudink, and huc, respectively (Shiau et al., 2013, Muenzel et al., 2012). We determined which of these constructs could rescue microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants in transient Tol2 transgenic experiments: constructs were injected into mutants and wildtype siblings, then scored by neutral red staining at 5 dpf. Because some microglia are present in rragast77/st77 mutants, an individual mutant was scored as rescued if it had 15 or more neutral-red stained microglia. Expression of wildtype rraga under the control of mpeg1 sequences rescued all injected mutants (n=10), whereas expression in oligodendrocytes or neurons produced little evidence of rescue (Fig. 2I). In summary, our marker studies and transgenic rescue experiments indicate that rraga acts cell-autonomously at an early stage of microglia development.

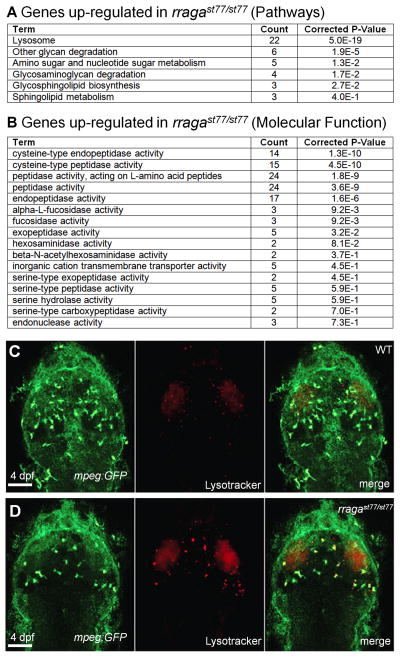

Abnormal accumulation of lysosomal organelles in microglia of rragast77/st77 mutants

In order to investigate the pathways that are disrupted in the absence of RagA, we employed RNA sequencing to identify changes in the transcriptome of rragast77/st77 mutants. To prepare RNA for sequencing, we used neutral red staining to distinguish rragast77/st77 mutants and wildtype siblings at 5 dpf, and isolated RNA from four pools of siblings, each of which contained 10 wildtype or 10 mutant larvae (WT: n=2 pools, mutant: n=2 pools). We used the Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing system to obtain 50-nt paired-end reads (>20 million reads per sample) and the Tuxedo Suite pipeline (Trapnell et al., 2012) for data analysis. Using a cut-off of >1.5-fold difference of FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) values (averaged from the duplicate pools), we identified 208 genes that were up-regulated and 41 genes down-regulated in the rragast77/st77 mutants. Functional annotation with DAVID Bioinformatic Resources revealed that the most significantly up-regulated genes were related to lysosomal activity (Fig. 3A, 3B). In order to determine if lysosomes are dysregulated in microglia, we utilized Lysotracker Red to examine lysosomal number and morphology in 4 dpf larvae in vivo. The rragast77/st77 mutants had markedly enlarged lysosomes in microglia, as indicated by comparison of Lysotracker Red staining and the Tg(mpeg1:EGFP) reporter in 4 dpf rragast77/st77 mutants and wildtype siblings (Fig. 3C, D). Thus the combination of RNA sequencing and cellular studies indicated that lysosomal compartment is increased in microglia of rragast77/st77 mutants.

Figure 3. Dysregulated lysosomal activity in microglia of rragast77/st77 mutants.

(A–B) Analysis of RNA sequencing data revealed that genes associated with lysosomal activity are significantly upregulated genes in rragast77/st77 mutants at 5 dpf. Using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resources, genes showing at least a 1.5-fold upregulation were classified accord (A) Kegg Pathway terms and (B) molecular functions (GOTERM_MF_FAT). (C–D) Visualization of Lysotracker Red and Tg(mpeg1:EGFP) in wildtype (C, n = 4) and rragast77/st77 mutants (D, n = 4) reveals that lysosomes are increased in microglia in the mutants. Larvae shown in C and D were genotyped by PCR after photography.

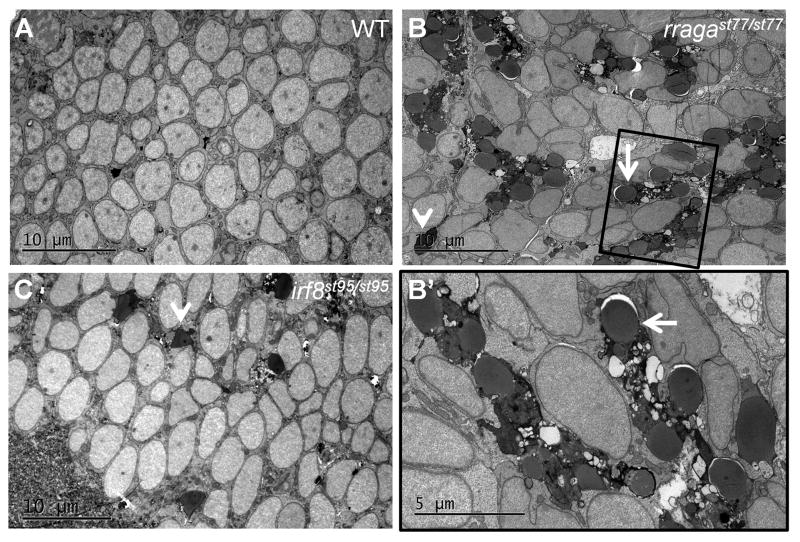

To further explore the expanded lysosomes in microglia, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in rragast77/st77 mutants (Fig. 4; Supp. Fig. 4). Microglia in the dorsal midbrain of rragast77/st77 mutants had an extremely abnormal morphology, with abundant, electron-dense vaculolar structures that we hypothesized to be phagolysosomes filled with undigested debris within microglial cells (Fig. 4B, B′). In addition, rragast77/st77 mutants also had an excess of unengulfed apoptotic neurons interspersed among other cells in the CNS (Fig. 4B arrowhead). To compare the rragast77/st77 mutants with abnormal microglia with a different mutant that lacks microglia, we also analyzed irf8st95/st95 mutant larvae, in which microglia are absent (Shiau et al., 2015). As expected, the irf8st95/st95 mutants had unengulfed apoptotic neurons but lacked the abnormal vacuole-laden microglia characteristic of rragast77/st77 mutants (Fig. 4C). To further characterize the apoptotic neurons in these mutants, we performed acridine orange staining, which marks apoptotic cells in live larvae. Both rragast77/st77 and irf8st95/st95 mutants had excess undigested cellular debris (Supp. Fig. 3), but rragast77/st77 mutants had in addition larger clusters of debris within microglial cells. Thus, both ultrastructural analysis and acridine orange staining suggested that the microglia present in rragast77/st77 mutants accumulate large numbers of vacuolar organelles containing apoptotic neuronal debris. In addition, the undigested vacuolar debris in rragast77/st77 mutant microglia suggested that lysosomal function is impaired in rragast77/st77 mutants.

Figure 4. Abnormal vacuolar organelles in microglia and uncleared apoptotic neurons in rragast77/st77 mutants.

Transmission electron micrographs of the dorsal midbrain of (A) WT, (B, B′) rragast77/st77, and (C) irf8st95/st95 larvae at 4 dpf. Boxed region in B is shown at higher magnification in B′. Microglia in the rragast77/st77 mutants have a striking accumulation of vacuolar organelles that appear to contain undigested material (white arrows). Microglia were absent in the irf8 mutant. In both mutants uncleared corpses of apoptotic neurons are present (white arrowheads). These phenotypes were also evident in mutants stained with acridine orange (Supp. Fig. 3). Toluidene blue stained sections of the same larvae are shown in Supp. Fig 4. Larvae were genotyped by PCR from tail biopsies collected immediately prior to fixation.

RagA is Essential for Microglia to Digest Apoptotic Neurons

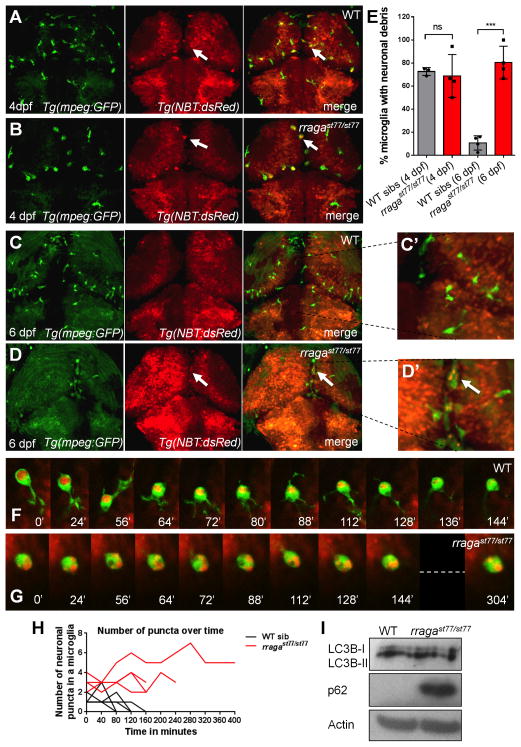

To test the hypothesis that microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants are able to engulf apoptotic neurons but unable to digest them properly, we analyzed mutants containing different transgenic reporters for neurons and microglia. As in previous studies (Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008), we used Tg(mpeg:GFP) and Tg(nbt:dsRed) to mark microglia and neurons, respectively. At 4 dpf, microglia contained neuronal debris in both wildtype and rragast77/st77 mutants, indicating that rragast77/st77 mutant microglia are able to engulf neuronal material (Fig. 5A, B, E). By 6 dpf, most of the microglia wildtype larvae had digested the neuronal material they engulfed (Fig. 5C, C′, D, D′), but a majority of microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants still contained undigested neuronal material (Fig. 5D, E). To directly analyze digestion of neuronal debris in microglia, we performed time-lapse imaging of wildtype and mutant larvae bearing the two transgenes at 4–4.5 dpf. In wildtype larvae, microglia were continuously engulfing and digesting neuronal material, and neuronal debris appeared to be digested two to three hours after engulfment (Fig. 6F, H). In contrast, microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants did not digest engulfed neuronal material in the same time frame (Fig. 6G, H).

Figure 5. Accumulation of undigested neuronal material in microglia of In rragast77/st77 mutants.

(A–D, G, H) Confocal images of living larvae bearing transgenes that label neurons Tg(nbt:DsRed) and microglia Tg(mpeg1:EGFP). In wildtype (A, C) and rragast77/st77 mutant (B, D) larvae, arrows indicate microglia that contain neuronal material. In wildtype larvae, more microglia contain neuronal material at 4 dpf (A, E) than at 6 dpf (C, C′, E), whereas most microglia in mutants contained neuronal material at both 4 dpf and 6 dpf (B, D, D′, E). Each point in E represents the data from one larva. (F, G) Frames from timelapse movies of WT (F) and rragast77/st77 (G) mutant larvae starting at 4 dpf, with timepoints indicated in minutes. (H) Quantification of the number of neuronal puncta inside microglia in timelapse movies of wildtype and rragast77/st77 mutant larvae. Each line represents a single microglia (WT: n = 4 cells from 3 larvae; mutant: n = 4 cells from 3 larvae). (I) Immunoblot blot of whole-animal protein lysates at 5 dpf shows normal LC3-I to LC3-II conversion, but an accumulation of p62 in rragast77/st77 mutants. Actin is shown as a loading control. All larvae shown in A–H were genotyped by PCR after photography. Larvae analyzed in the immunoblot (I) were genotyped as described in Experimental Procedures.

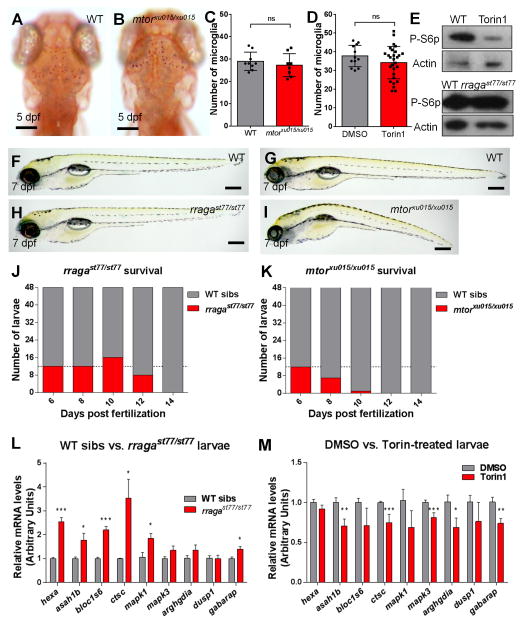

Figure 6. Distinct phenotypes of mtorxu015/xu015 and rragast77/st77 mutants.

(A–B) Images of living neutral red stained (A) WT and (B) mtor mutant larvae at 5 dpf. Dorsal views, anterior to the top. (C, D) There was no significant reduction of the number of microglia at 5 dpf in mtor mutants or wildtype animals treated with the mTOR inhibitor Torin1. (E) Immunoblots blots of 5 dpf whole animal protein lysates showing reduction of phospho-S6p levels after Torin1 treatment compared to control DMSO treatment. The level of phospho-S6p was similar in rragast77/st77 mutants and their wildtype siblings. Actin is shown as a loading control. (F–I) Lateral views of living larvae at 7 dpf, showing normal morphology of rragast77/st77 mutant (G) and abnormal morphology of mtorxu015/xu015 mutant (H), compared to their wildtype siblings (F and G, respectively). (J, K) Analysis of survival of (J) rragast77/st77 and (K) mtorxu015/xu015 mutants. Progeny of intercross of heterozygotes were raised, and 48 animals were genotyped by PCR for the mutant lesions at the indicated time points. Very few mtorxu015/xu015 mutants survived to 10 dpf, but most rragast77/st77 mutants survived to 12 dpf. For a homozygous viable mutation, 12 mutants would be expected at each time point on average (dotted lines). (L) Quantitative RTPCR of whole-animal RNA samples at 5 dpf showed an increase in expression of some target genes of the lysosomal transcription factor TFEB in rragast77/st77 mutants relative to their wildtype siblings. (M) Similar quantitative RTPCR did not detect any increased expression of the genes analyzed in mtorxu015/xu015 mutants, and many were significantly reduced. Error bars show s.e.m. of samples analyzed in triplicate. Statistical significance determined by a two-tailed t-test (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.005). All scale bars are 50μm. All larvae analyzed in A–C and E–J were genotyped by PCR. rragast77/st77 mutants analyzed in the immunoblot (E) were genotyped as described in Experimental Procedures. rraga mutants analyzed by RT-PCR were identified by neutral red staining prior to RNA isolation.

Functional lysosomes are essential for the proper progression of phagocytosis and autophagy. To further examine the possibility that rragast77/st77 mutants are able to initiate but not complete the degradation of material in lysosomes, we examined LC3 cleavage, which occurs with the formation of the phagosome or autophagosome, and p62 protein levels, which decline as phagosome substrates are degraded (Bjørkøy et al., 2009). In immunoblots of 5 dpf larvae lysates, LC3B was processed similarly in wildtype and rragast77/st77 mutants, indicating that the formation of phagosomes or autophagosmes are similar in wildtype and rragast77/st77 mutants (Fig. 5I). In contrast, p62 accumulates to much higher levels in rragast77/st77 mutants than wildtype, indicating that RagA is essential for lysosomal degradation of phagocytic or autophagy substrates (Fig. 5F). In summary, our analysis indicates that RagA is essential for normal lysosomal activity, such that lysosomal organelles accumulate at high levels in microglia of rragast77/st77 mutants but are nonetheless unable to digest engulfed debris.

Mutational Analysis Defines Distinct Functions for the Rag-Ragulator Complex and mTOR In Vivo

In light of previous evidence that the Rag-Ragulator complex functions in the activation of the mTORC1 pathway (Sancak and Sabatini, 2009), we wanted to determine if defective mTOR signaling caused the defects we observed in the absence of RagA and Lamtor4 function. Therefore we compared the phenotypes caused by mutations in rragast77/st77 and mtorxu015/xu015, using the previously identified mtorxu015 insertional allele (Ding et al., 2011). This analysis revealed several differences in the mutant phenotypes (Fig. 6). At 5 dpf, mtorxu015/xu015 mutants did not exhibit the reduction in microglia characteristic of rragast77/st77 and lamtor4st99/st99 mutants (Fig. 6A–C). In addition, microglia were present in normal numbers in wildtype larvae treated with Torin1 (Thoreen et al., 2009), a potent and specific inhibitor of mTOR signaling (Fig 6D). As reported in a previous study (Ding et al., 2011), we found that the mtorxu015/xu015 mutants had abnormal overall morphology at 7 dpf, and that only a few homozyogous mutants survived at 10 dpf (Fig. 6G, I, K). In contrast, rragast77/st77 mutants had normal morphology at 7 dpf and survived until 12–13 dpf (Fig 6F, H, J). In addition, rragast77/st77 mutants had apparently normal levels of phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 (Fig. 6E), which is decreased in the absence of mTOR signaling (Kim et al., 2014).

We also investigated target genes of TFEB, a transcriptional regulator of lysosome biogenesis and function (Settembre et al., 2011, Martina and Puertollano, 2013), in rragast77/st77 and mtorxu015/xu015 mutants. In support of our RNA sequencing results, rragast77/st77 mutants had significantly increased expression of many of the TFEB target genes tested, including hexa, asah1b, bloc1s6, ctsc, mapk1, and gabarap (Fig. 6L). In contrast with rragast77/st77 mutants, larvae treated with Torin1 from 1–5 dpf had slightly reduced expression of many of these genes, including asah1b, ctsc, and gabarap (Fig. 6M). In summary, our phenotypic studies indicate that the Rag-Ragulator complex has essential functions in microglia development and lysosome activity that are independent of mTOR activity.

Discussion

Our mutational analysis defines RagA and Lamtor4, two components of the lysosome-tethered Rag-Ragulator complex, as essential regulators of lysosome biogenesis and function in microglia. Much attention has focused on the role of the Rag-Ragulator complex in regulating mTOR activity (Sancak and Sabatini, 2009), but our analysis indicates that mutants lacking RagA and Lamtor4 share phenotypes that are distinct from mTOR mutants. In mutants lacking Rag-Ragulator function, abnormal lysosomal organelles accumulate, and microglia are unable to digest debris from apoptotic neurons. Clearance of apoptotic cells, protein aggregates, and other debris is disrupted in neurodegenerative disease and other CNS pathologies (Ransohoff and Perry, 2009). Our results define essential regulators of the phagocytic function of microglia in vivo and provide important insights into clearance of debris in the CNS. We demonstrate that the Rag-Ragulator complex is a central regulator of lysosomal activity that is essential for microglia to maintain homeostasis in the brain.

The Rag-Ragulator Complex Functions Independently of mTOR as a Central Regulator of Lysosomal Activity

The Rag-Ragulator complex is best known for its role in activating mTORC1 signaling in response to lysosomal amino acid levels. The Ragulator complex tethers Rag GTPases to the cytoplasmic surface of the lysosome and serves as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that activates Rag proteins as amino acids translocate through a v-ATPase in the lysosomal membrane (Zoncu et al., 2011). Activated Rag proteins recruit mTORC1 to the lysosome surface, where it is activated by Rheb (Sancak et al., 2008). In vivo studies also demonstrate a link between RagA activity and mTORC1 activity. In newborn mice expressing constitutively active RagA, mTORC1 signaling is also constitutively active, blocking the initiation of autophagy and causing perinatal lethality (Efeyan et al., 2013). In loss-of-function studies, however, mTORC1 was active in cells from RagA knockout mutant mice, indicating that Rag-independent mechanisms can also promote mTORC1 activity (Efeyan et al., 2014). Similarly, we also showed that mTORC1 signaling is apparently normal in rragast77/st77 mutant larvae (Fig. 6E). The mechanisms that activate mTOR in the absence of Rag-Ragulator activity remain to be elucidated, but there is evidence that Rheb can localize and activate mTOR at the lysosome in conditions when the Rag proteins are inactive (Demetriades et al. 2014).

Despite evidence connecting the Rag-Ragulator complex and mTORC1, our analysis and that of others (Kim et al., 2014) demonstrate that the Rag-Ragulator complex has functions independent of mTORC1. rragast77/st77 and lamtor4st99/st99 mutants had similar reduction in microglia number, whereas mtorxu015/xu015 mutants and Torin1-treated larvae had normal numbers of microglia and a distinct morphological phenotype at early larval stages (Fig. 6A–E). Thus, our analysis provides genetic evidence complementing previous biochemical studies that implicate Rag GTPases and the Ragulator complex in shared functions. However, our evidence also indicates that mTORC1 is not a downstream effector of RagA in the regulation of microglial lysosomes.

Our analysis extends an interesting study showing distinct functions for Rag GTPases and mTORC1 in the heart (Kim et al., 2014). Kim et al. demonstrated that Rag GTPases regulate lysosomal activity in cardiomyocytes and that loss of RagA and RagB specifically in cardiomyocytes causes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Kim et al., 2014). Furthermore, mTORC1 is active in fibroblasts obtained from RagA knockout mice (Efeyan et al., 2014). Thus, the combined results demonstrate that Rag GTPases have an essential, mTOR-independent function in lysosome regulation that encompasses specialized cell types as distinct as cardiomyocytes and microglia.

The Rag-Ragulator Complex is Essential for Lysosome Function in Different Cell Types

Our RagA and Lamtor4 mutants reveal novel roles of the Rag-Ragulator complex in microglia development. Zebrafish lacking RagA or Lamtor4 have a reduced number of microglia (Fig. 1A–F). In rragast77/st77 mutants, this reduction is evident with different markers of macrophages and microglia including neutral red staining, apoe, slc7a7, and mpeg1:gfp (Fig. 2A–F). At 3 dpf, the number of mfap4-expressing cells in the brain is reduced in rragast77/st77 mutants (Fig. 2G, H), indicating that RagA is important when primitive macrophages start differentiating as microglia. As they differentiate, microglia begin engulfing apoptotic neurons (Herbomel et al. 2001), and it is possible that impaired digestion of neuronal debris causes the death of microglia or reduces their proliferation. There is evidence that the lysosome is important for microglial migration (Dou et al., 2011), so it is also possible that defects in migration contribute to the reduction in microglia in mutants that lack RagA.

Although rraga mRNA is provided maternally and expressed widely in the embryo (Supp. Fig. 2A and 2B), the overall morphology of zygotic rragast77/st77 mutants is normal, and they typically survive to 12 dpf. Our analysis shows that RagA has a specific, autonomous function in microglia, but it is likely that RagA has essential functions in other cell types as well. While rragast77/st77 mutants did not survive to 14 dpf, other mutants lacking microglia are viable at this stage (Shiau et al., 2014). This suggests that the lethality of rragast77/st77 mutants is caused by lysosomal dysfunction in other cell types, including cardiomyocytes (Kim et al., 2014). Future studies are needed to characterize the function of the Rag-Ragulator in different cell types and determine the basis of the lethality of rraga mutations.

Lysosomes have wide-ranging cellular functions that are deployed in different ways in different cell types according to their physiological specializations (Settembre et al., 2013). Specialized phagocytic cell types such as macrophages and microglia have abundant lysosomes that are essential for these cells to carry out their functions in immunity and debris-clearance (Appelqvist et al., 2013). These immune cells are therefore highly dependent on proper lysosome function. In other cell types, such as muscle, lysosomal activity is required to recycle nutrients like glycogen (Nascimbeni et al., 2012). Lysosomal activity also increases during certain conditions, such as exercise and starvation, when a cell recycles its own organelles during autophagy (He et al., 2012). Thus, control of lysosome activity operates on multiple levels that are likely to vary in cells with different functions and physiological specializations. We propose that the Rag-Ragulator complex is a key regulator of lysosome biogenesis in many diverse cell types, and that their dysfunction will manifest as cell-type specific phenotypes in different stages or conditions.

Mechanism of Action of the Rag-Ragulator Complex

The Rag-Ragulator complex directly interacts with several proteins, including some that are integral parts of the lysosome, such as the v0 subunit of the v-ATPase (Zoncu et al., 2011), and others that are recruited to the lysosome under specific conditions, such as mTORC1 and the TFEB transcription factor (Martina et al., 2013). As discussed above, our analysis indicates that the Rag-Ragulator complex has an mTORC1-independent function in regulating microglial lysosomes, prompting us to consider the possible roles of TFEB and the v-ATPase.

The transcription factor TFEB controls the expression of genes in the CLEAR (Coordinated Lysosome Expression and Regulation) network, which regulates lysosome biogenesis and function (Palmieri et al., 2011). Our analysis indicates that expression of TFEB target genes was increased in rragast77/st77 mutants (Fig. 6K), contrasting with the normal or reduced expression of these genes in Torin1-treated larvae (Fig. 6L). Previous work with cultured cells showed that Rag heterodimers recruit TFEB to the lysosome, where it is inactivated and prevented from entering the nucleus in nutrient-rich conditions (Martina and Puertollano, 2013). Our finding that TFEB target genes are increased in rragast77/st77 mutants support and extends previous work (Kim et al., 2014) suggesting that mutation of RagA increases TFEB activity in vivo. Similar to our analysis of rraga mutant zebrafish, previous analysis of RagA/B mutant mouse embryonic fibroblasts revealed that TFEB activity was increased even though autophagic flux and lysosomal acidification were impaired in the absence of Rag function (Kim et al., 2014). Thus, TFEB may be activated by a feedback mechanism that expands the lysosomal compartment in response to the impaired digestion of neuronal debris in rragast77/st77 mutants. According this view, TFEB activation is a response to the lysosomal impairment in rragast77/st77 mutants, not the cause. Thus it seems likely that the Rag-Ragulator complex must control lysosomal activity through other effectors.

Based on our analysis and that of others, we propose that the interaction between the Rag-Ragulator complex and the v-ATPase is critical for lysosomal activity in microglia. The Ragulator complex binds to the v-ATPase (Zoncu et al., 2011), which acidifies lysosomes and allows degradation of the material they contain. Previous work shows that lysosomes are slightly less acidified in the absence of Rag GTPases (Kim et al., 2014). Thus, impaired acidification could explain the debris-laden lysosomal organelles we observed in microglia of rragast77/st77 mutants, and increased TFEB activity could explain why these organelles accumulate (Fig. 3). It is also possible, however, that the interaction between the Rag-Ragulator complex and the v-ATPase is essential for the fusion between phagosomes containing neuronal debris and lysosomes. A previous study reported that the v0-ATPase a1 subunit, also found on lysosomal membranes, is important for the fusion of phagosomes and lysosomes to form the phagolysosomes that digest engulfed debris (Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008). In addition, analysis of Rag homologues Gtr1p and Gtp2p in yeast provides a precedent for a role of Rag GTPases in vesicular trafficking (Gao and Kaiser, 2006). Thus, interaction between the Rag-Ragulator complex and the v-ATPase may be essential for proper vesicular acidification, fusion, trafficking, or a combination of these.

Rag-Ragulator Complex and Lysosomal Diseases

Our analysis points to a key role of the Rag-Ragulator complex in lysosome function and activity in microglia. RNA-sequencing reveals an increased expression of lysosomal genes in rragast77/st77 mutants, including genes regulating the biosynthesis of lysosomes and genes encoding lysosomal enzymes (Fig. 3A–B). Lysotracker Red also reveals an expanded lysosomal compartment in microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants (Fig. 3C–D). Despite the increase in lysosomal gene expression and markers, microglia in rragast77/st77 mutants do not properly digest neuronal debris, indicating that the excess lysosomal organelles accumulating in the mutants are dysfunctional. The few microglia present in rragast77/st77 mutants are able to ingest but not digest debris from apoptotic neurons (Fig. 5). The engorged, dysfunctional lysosomes observed in rragast77/st77 mutant microglia are reminiscent of pathologies in patients with diseases of the CNS (Bae et al., 2014).

Lysosomes are critical for the function of phagocytic cells, but they also play essential roles in almost all other eukaryotic cells. Lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) are Mendelian hereditary diseases caused by improper lysosome function (Cox and Cachón-González, 2012). About two-thirds of LSDs affect the CNS (Meikle et al., 1999), underscoring the importance of lysosomes in CNS homeostasis, but other organs are also affected. For example, glycogen accumulation in cells of patients with Pompe disease cause impaired function in those organs, and a similar phenotype was observed in RagA/RagB double knock-out cardiomyocytes (Kim et al., 2014). The different manifestations of Rag loss-of-function in muscle and microglia reflect the different roles of lysosomes in recycling of nutrients such as glycogen in muscle (Nascimbeni et al., 2012, Kim et al., 2014), and clearing neuronal debris in microglia (Fig. 5).

In addition to the LSDs, microglial function is involved in many common CNS pathologies. For example, recovery after CNS injury hinges on the effective clearance of cellular debris by microglia (Bruce-Keller, 1999, Vargas and Barres, 2007). Furthermore, the abnormal accumulation of Aβ plaques and other proteins underlies the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative diseases (Heppner et al., 2015). Evidence implicates microglia in these diseases, both as drivers of neuroinflammation and also because their phagocytic activity and ability to maintain homeostasis is impaired in Alzheimer models. Further investigation is required to assess the timing and relative importance of impaired phagocytosis and abnormal inflammation in Alzheimer disease and other diseases. We analyzed zebrafish mutants in which phagocytic microglial cells have abnormal lysosome function, resulting in an accumulation of neuronal debris. Our mutants represent new models to investigate the pathological implications of debris-laden microglia and to investigate possible autonomous lysosomal defects in neurons and other cell types.

Protein complexes that assemble on the lysosome control diverse functions beyond lysosome integrity and function, and the lysosome is increasingly recognized as a signaling platform (Appleqvist et al., 2013, Settembre et al., 2013). Our mutational analysis has provided a new understanding of the role of the Rag-Ragulator complex in microglial lysosomes. In addition, the identification of Rag-Ragulator mutants provides an opportunity to dissect the roles of the lysosome in diverse cell types in vivo, which will elucidate pathophysiological processes and suggest avenues toward therapies for lysosomal disorders.

Experimental Procedures

Zebrafish Lines and Maintenance

All work with zebrafish was conducted with approval from the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Embryos and larvae were treated with 0.003% 1-phenyl-2-thiourea (PTU) to inhibit pigmentation, and anesthetized with 0.016% (w/v) Tricaine prior to experimental procedures. The mtorxu015 line was obtained from the Xu lab and genotyped by PCR as described (Ding et al., 2011). The transgenic lines Tg(mpeg1:eGFP) and Tg(NBT:dsRed) were previously described (Ellett et al., 2011, Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008).

ENU Mutagenesis Screen

Founder males were treated with N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) as described (Pogoda et al., 2006). As described in previous reports (Paavola et al., 2014, Shiau et al., 2013, Meireles et al., 2014), we used neutral red staining and in situ hybridization for mbp mRNA to conduct two parallel F3 genetic screens for mutants with abnormalities in microglia or myelinating glia, respectively.

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization on embryos and larvae was performed using standard methods (Thisse et al., 2004). Embryos were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated for at least 2h in 100% methanol, rehydrated in PBS, permeabilized with proteinase K, and incubated overnight with antisense riboprobes at 65°C. The probe was detected with an anti-digoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. Images were captured using the Zeiss AxioCam HRc camera with the AxioVision software. Probes for mfap4 and apoe were previously described (Zakrzewska et al., 2010, Shiau et al., 2013). Primers used to generate probes for rraga and slc7a7 are found in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Genetic mapping and molecular characterization of mutations

Mutant rragast77/st77 and lamtor4st74/st74 mutants were sorted from wildtype and heterozygous siblings based on lack of mbp expression in the central nervous system (CNS). The mutations were mapped by analyzing simple sequence length polymorphisms (SSLPs) using standard methods (Talbot and Schier, 1999), and subsequent high resolution mapping and sequencing studies identified the st77 lesion in rraga (NM_199714) and st74 lesion in lamtor4 (NM_001044950). The st77 lesion was genotyped by PCR amplification of genomic DNA (primers: forward 5′-TGGTTCAGGAGGATCAGAGAG-3′, reverse 5′-CAAAAGCAGACAATGCAAAAC-3′), followed by incubation with the restriction enzyme MspA1I, which cleaves the wildtype allele. The st74 lesion was genotyped by PCR (primers: forward 5′-TTTATCTGCACTGTCTAAAATGGT-3′, reverse 5′-CGCGAGTACTCCGTCTTCACTA-3′) followed by sequencing to detect the lesion.

TALEN-targeting to create st110 and st99 mutations

The TAL Effector-Nucleotide Targeter 2.0 (Doyle et al., 2012, Cermak et al., 2011) webtool was used to design a pair of transcription activator-like effector nucleases to target the exon1-intron boundary of the rraga gene, and exonic regions of lamtor4. The Golden Gate cloning protocol for creating the TALEN plasmids was used (Sanjana et al., 2012). Plasmids were then transcribed using Sp6 mMessage mMachine Kit by Ambion. 400ng of mRNA were injected into 1-cell stage wildtype TL embryos, which were raised to adulthood. To identify founders carrying a null mutation in the germline, we cross injected fish to TLs and genotyped a subset of the progeny at 2–3 dpf. To genotype st110, genomic DNA was amplified by PCR (primers: forward 5′-GCAGCCGCACAAACTTTGATATT-3′ and reverse 5′-TGCAGTATGGCTTCCAGACACAA-3′) and incubated with BspH1, which cleaves the wildtype but not the mutant allele. Based on the disruption of the BspH1 restriction site, we identified founders and raised the remaining F1 progeny to adulthood. Sequencing identified an F1 heterozygous for 16-bp deletion, which was crossed to TL to establish a stock. Similar protocols were used to generate st99; the mutation was identified by PCR of genomic DNA (primers: forward 5′-TTTATCTGCACTGTCTAAAATGGT-3′, reverse 5′-CGCGAGTACTCCGTCTTCACTA-3′), followed by digestion with DpnII.

Immunoblots

Antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (RagA [4357], phospho-S6 ribosomal protein [5364], p62/SQSTM [5114] and Sigma-Aldrich (beta-Actin [A5316], LC3B [L7543]). Larvae were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer with DTT, phosphatase inhibitors and protease inhibitors and resolved on 4–12% NuPage® Bis-Tris Precast Gels (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies were used at a 1:1000 dilution and incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by detection HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies.

To genotype larvae from rraga mutant crosses, tail biopsies were collected from individual anesthetized larvae at 5 dpf. Biopsies from individual fish were placed directly into lysis buffer to prepare DNA, and the remaining portion of each corresponding sample was frozen immediately on dry ice. After genotyping the individuals by PCR and MspA1I digestion, wildtype and mutant pools (10 individuals in each pool) were homogenized as described above.

Confocal fluorescent imaging

Zebrafish embryos were mounted in 1.5% low melting point agarose in distilled water. Images were captured using a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal or Zeiss LSM confocal microscope. Objectives used were Plan-Neofluar 10x (numerical aperture 0.30) and 20x (numerical aperture 0.75).

RNA sequencing

Wildtype and rraga mutant larvae at 5 dpf were distinguished by neutral red staining and pooled for RNA isolation. Duplicate wildtype and mutant RNA samples (from 4 pools total) were provided to the Stanford Functional Genomics Facility, which prepared libraries and sequenced them with the Illumina Hi-Seq 2000 to obtain 50-nt paired ends reads. The numbers of reads obtained were: wildtype1-23078044, mutant1-28491733, wildtype2-26485359, mutant2-20836883. Sequencing data was analyzed using the Tuxedo Suite pipeline (Bowtie, Tophat, Cufflinks) as described (Trapnell et al., 2012), to obtain FPKM values.

Drug treatment and staining with LysoTracker and Acridine Orange

Larvae at 4 dpf were incubated in a 1:100 dilution of LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen) in embryo water at 28.5°C for 45 min to 1 hour, then washed twice with embryo water before live imaging. For Torin1 treatment, wildtype fish were incubated in 1uM Torin1 (Torcris Biosciences) in embryo water from 24 hpf to 5 dpf; fresh embryo medium and Torin1 were added daily. Living larvae at 4 dpf were stained with acridine orange as described (Peri and Nüsslein-Volhard, 2008).

Transmission Electron Microscopy and Toluidine Blue staining

TEM was performed as described (Lyons et al., 2008). Briefly, decapitated embryos were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4. The posterior portion of the larvae was used to isolate DNA for genotyping. For secondary fixation, samples were fixed in 2% osmium tetraoxide, 0.1M imidazole in 0.1M sodium cacodylate pH7.4, stained with saturated uranyl acetate and dehydrated in ethanol and acetone. Fixation and dehydration were accelerated using the PELCO 3470 Multirange Laboratory Microwave System (Pelco) at 15°C. Samples were then incubated in 50% Epon/50% acetone overnight, followed by 100% Epon for 4h at room temperature. Samples were then embedded in 100% Epon and baked for 48 h at 60°C. Blocks were sectioned using a Leica Ultramicrotome. Thick sections (500–1000μm) for Toluidine blue staining were collected on glass slides, stained at 60°C for 5 seconds and imaged with the Leica DM 2000 microscope using the Leica DFC290 HD camera and Leica Application Suite software. After the desired region of the brain was reached, we collected ultrathin sections for TEM analysis on copper grids, and stained them with uranyl acetate and Sato’s lead stain (1% lead citrate, 1% lead acetate, 1% lead nitrate). Sections were imaged on a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope.

Quantitative RTPCR

Total RNA were extracted from larvae at 5 dpf with the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen). Wildtype and rraga mutants were distinguished by neutral red staining. cDNA was transcribed with oligo dT primers using the Superscript III kit (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed with SsoAdvancedTM Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on the Bio-Rad CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System. Primers are listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

The Rag-Ragulator Complex is Essential for Microglia Development and Function

Rag GTPases have Functions independent of mTORC1

The Rag-Ragulator Complex is a Central Regulator of Lysosomal Activity

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ana M. Meireles, Celia E. Shiau, Daniel E. Lysko, John J. Perrino, Brandon J. Carter and Qianyi Lee for helpful discussions and technical advice, Tuky K. Reyes and Chenelle Hill for fish maintenance, and Beninio T. Gore and Xiaolei Xu for mtor mutant fish. K.S. and H.S. are supported by fellowships from A*STAR Singapore. W.S.T. is a Catherine R. Kennedy and Daniel L. Grossman Fellow in Human Biology. This work was supported by NIH grants R01NS050223 and R56HL125040 and NMSS grant RG-4756-A-3 to W.S.T.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

H.S. conducted the screen and molecular analysis of the lamtor4 mutations. K.S. performed molecular analysis of the rraga mutations. K.S. performed all phenotypic analysis and other studies. K.S. and W.S.T. analyzed results and wrote the manuscript with input from H.S.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguzzi A, Barres BA, Bennett ML. Microglia: Scapegoat, Saboteur, or Something Else? Science. 2013;339(6116):156–161. doi: 10.1126/science.1227901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelqvist H, Wäster P, Kågedal K, Öllinger K. The lysosome: from waste bag to potential therapeutic target. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2013;5(4):214–226. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae M, Patel N, Xu H, Lee M, Tominaga-Yamanaka K, Nath A, Haughey NJ. Activation of TRPML1 clears intraneuronal Aβ in preclinical models of HIV infection. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(34):11485–503. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0210-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio A, Gieselmann V. Lysosomal disorders: From storage to cellular damage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2009;1793(4):684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell. 2012;150(6):1196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ. Microglial–neuronal interactions in synaptic damage and recovery. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:191–201. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19991001)58:1<191::aid-jnr17>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørkøy G, Lamark T, Pankiv S, Øvervatn A, Brech A, Johansen T. Chapter 12 Monitoring Autophagic Degradation of p62/SQSTM1. In: BTM, editor. Enzymology Autophagy in Mammalian Systems, Part B. Vol. 452. Academic Press; 2009. pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cermak T, Doyle EL, Christian M, Wang L, Zhang Y, Schmidt C, Baller JA, Somia NJ, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert JD, Matthews SP, Miller G, Watts C. Diverse regulatory roles for lysosomal proteases in the immune response. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39(11):2955–2965. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMattos RB, Lu J, Tang Y, Racke MM, Delong CA, Tzaferis JA, Hutton ML. A plaque-specific antibody clears existing β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neuron. 2012;76:908–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriades C, Doumpas N, Teleman AA. Regulation of TORC1 in response to amino acid starvation via lysosomal recruitment of TSC2. Cell. 2014;156:786–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Sun X, Huang W, Hoage T, Redfield M, Kushwaha S, Xu X. Haploinsufficiency of target of rapamycin attenuates cardiomyopathies in adult zebrafish. Circulation research. 2011;109(6):658–69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Wu H, Li H, Qin S, Wang Y, Li J, Duan S. Microglial migration mediated by ATP-induced ATP release from lysosomes. Cell Research. 2012;22(6):1022–1033. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle EL, Booher NJ, Standage DS, Voytas DF, Brendel VP, VanDyk JK, Bogdanove AJ. TAL Effector-Nucleotide Targeter (TALE-NT) 2.0: tools for TAL effector design and target prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 doi: 10.1093/nar/gks608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellett F, Pase L, Hayman JW, Andrianopoulos A, Lieschke GJ. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood. 2011;117(4):e49–e56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Chang S, Gumper I, Snitkin H, Wolfson RL, Sabatini DM. Regulation of mTORC1 by the Rag GTPases is necessary for neonatal autophagy and survival. Nature. 2013;493(7434):679–83. doi: 10.1038/nature11745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efeyan A, Schweitzer LD, Bilate AM, Chang S, Kirak O, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM. RagA, but not RagB, is essential for embryonic development and adult mice. Dev Cell. 2014;29:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannagan RS, Jaumouillé V, Grinstein S. The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annual review of pathology. 2012;7:61–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Kaiser CA. A conserved GTPase-containing complex is required for intracellular sorting of the general amino-acid permease in yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(7):657–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science of Aging Knowledge Environment. 2002;2002(29) doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, Levine B. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2012;481(7382):511–515. doi: 10.1038/nature10758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner FL, Ransohoff RM, Becher B. Immune attack: the role of inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):358–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn3880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Zebrafish Early Macrophages Colonize Cephalic Mesenchyme and Developing Brain, Retina, and Epidermis through a M-CSF Receptor-Dependent Invasive Process. Developmental Biology. 2001;238(2):274–288. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova S, Repnik U, Boji L, Petelin A, Turk V, Turk B. Chapter Nine Lysosomes in Apoptosis. In: BTM, editor. Enzymology Programmed Cell Death, General Principles for Studying Cell Death, Part A. Vol. 442. Academic Press; 2008. pp. 183–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nature cell biology. 2008;10(8):935–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Park HW, Sciarretta S, Mo JS, Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Rag GTPases are cardioprotective by regulating lysosomal function. Nature communications. 2014;5(May):4241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange Y, Ye J, Steck TL. Circulation of Cholesterol between Lysosomes and the Plasma Membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(30):18915–18922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth Control and Disease. Cell. 2015;149(2):274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J. Rheb Binds and Regulates the mTOR Kinase. Current Biology. 2005;15(8):702–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons DA, Naylor SG, Mercurio S, Dominguez C, Talbot WS. KBP is essential for axonal structure, outgrowth and maintenance in zebrafish, providing insight into the cellular basis of Goldberg-Shprintzen syndrome. Development. 2008;135(3):599–609. doi: 10.1242/dev.012377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A, Cruz D, Asamoah N, Buxbaum A, Sohar I, Lobel P, Maxfield FR. Activation of Microglia Acidifies Lysosomes and Leads to Degradation of Alzheimer Amyloid Fibrils. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18(4):1490–1496. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-10-0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina Ja, Puertollano R. Rag GTPases mediate amino acid-dependent recruitment of TFEB and MITF to lysosomes. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;200(4):475–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201209135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle PJ, Hopwood JJ, Clague AE, Carey WF. Prevalence of Lysosomal Storage Disorders. JAMA. 1999;281(3):249–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meireles AM, Shiau CE, Guenther Ca, Sidik H, Kingsley DM, Talbot WS. The Phosphate Exporter xpr1b Is Required for Differentiation of Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Cell reports. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451(7182):1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenzel EJ, Schaefer K, Obirei B, Kremmer E, Burton EA, Kuscha V, Becker CG, Broesamle C, Williams A, Becker T. Claudin k is specifically expressed in cells that form myelin during development of the nervous system and regeneration of the optic nerve in adult zebrafish. Glia. 2012;60(2):253–270. doi: 10.1002/glia.21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimbeni AC, Fanin M, Masiero E, Angelini C, Sandri M. Impaired autophagy contributes to muscle atrophy in glycogen storage disease type II patients. Autophagy. 2012;8(11):1697–1700. doi: 10.4161/auto.21691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paavola KJ, Sidik H, Zuchero JB, Eckart M, Talbot WS. Type IV collagen is an activating ligand for the adhesion G protein – coupled receptor GPR126. 2014;7(338):1–10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri M, Impey S, Kang H, di Ronza A, Pelz C, Sardiello M, Ballabio A. Characterization of the CLEAR network reveals an integrated control of cellular clearance pathways. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20(19):3852–3866. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peri F, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Live imaging of neuronal degradation by microglia reveals a role for v0-ATPase a1 in phagosomal fusion in vivo. Cell. 2008;133(5):916–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt FM, Boland B, van der Spoel AC. Lysosomal storage disorders: The cellular impact of lysosomal dysfunction. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2012;199(5):723–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201208152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogoda HM, Sternheim N, Lyons DA, Diamond B, Hawkins TA, Woods IG, Talbot WS. A genetic screen identifies genes essential for development of myelinated axons in zebrafish. Developmental Biology. 2006;298(1):118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial Physiology: Unique Stimuli, Specialized Responses. Annual Review of Immunology. 2009;27(1):119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, El Khoury J. Microglia in Health and Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A, Caler EV, Andrews NW. Plasma Membrane Repair Is Mediated by Ca2+-Regulated Exocytosis of Lysosomes. Cell. 2015;106(2):157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F, Casano AM, Henke K, Richter K, Peri F. The SLC7A7 Transporter Identifies Microglial Precursors prior to Entry into the Brain. Cell reports. 2015;11(7):1008–17. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141(2):290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. Rag Proteins Regulate Amino Acid-Induced mTORC1 Signaling. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2009;37(Pt 1):289–290. doi: 10.1042/BST0370289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist Ra, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science (New York, NY) 2008;320(5882):1496–501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjana NE, Cong L, Zhou Y, Cunniff MM, Feng G, Zhang F. A transcription activator-like effector toolbox for genome engineering. Nature protocols. 2012;7(1):171–92. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, Stevens B. Microglia Sculpt Postnatal Neural Circuits in an Activity and Complement-Dependent Manner. Neuron. 2012;74(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, Arencibia MG, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Ballabio A. TFEB Links Autophagy to Lysosomal Biogenesis. Science (New York, NY) 2011;332(6036):1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C, Fraldi A, Medina DL, Ballabio A. Signals from the lysosome: a control centre for cellular clearance and energy metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(5):283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau CE, Kaufman Z, Meireles AM, Talbot WS. Differential requirement for irf8 in formation of embryonic and adult macrophages in zebrafish. PloS one. 2015;10(1):e0117513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau CE, Monk KR, Joo W, Talbot WS. An anti-inflammatory NOD-like receptor is required for microglia development. Cell reports. 2013;5(5):1342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Rochford CDP, Neumann H. Clearance of apoptotic neurons without inflammation by microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201(4):647–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot WS, Schier AF. Postional cloning of mutated zebrafish genes. The Zebrafish: Genetics and Genomics. In: Detrich HW III, Westerfield M, Zon LI, editors. Methods Cell Biol. Vol. 60. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 259–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Heyer V, Lux A, Alunni V, Degrave A, Seiliez I, Kirchner J, Parkhill JP, Thisse C. Spatial and temporal expression of the zebrafish genome by large-scale in situ hybridization screening. The Zebrafish: Genetics, Genomics and Informatics, 2nd ed. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;77:505–519. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)77027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreen CC, Kang Sa, Chang JW, Liu Q, Zhang J, Gao Y, Gray NS. An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284(12):8023–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900301200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature protocols. 2012;7(3):562–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ME, Barres BA. Why is Wallerian degeneration in the CNS so slow? Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2007;30:153–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrzewska A, Cui C, Stockhammer OW, Benard EL, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Macrophage-specific gene functions in Spi1-directed innate immunity. Blood. 2010;116(3):e1–e11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-262873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Paolicelli RC, Sforazzini F, Weinhard L, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Gross CT. Deficient neuron-microglia signaling results in impaired functional brain connectivity and social behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(3):400–406. doi: 10.1038/nn.3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Sheng R, Qin Z. The lysosome and neurodegenerative diseases. Structure and Function of Lysosomes. 2009:437–445. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 Senses Lysosomal Amino Acids Through an Inside-Out Mechanism That Requires the Vacuolar H+-ATPase. Science. 2011;334(6056):678–683. doi: 10.1126/science.1207056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.