Abstract

Neutropenia after orthotopic liver transplantation (LT) is relatively common but the factors associated with its development remain elusive. We assessed possible predictors of neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] less than or equal to 1000/mm3) within the first year of LT in a cohort of 304 patients at a tertiary medical center between 1999 and 2009 using time-dependent survival analysis to identify risk factors for neutropenia. In addition, we analyzed neutropenia as a predictor of the clinical outcomes of death, blood stream infection (BSI), invasive fungal infection (IFI), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease and graft rejection within the first year of LT. Of the 304 LT recipients, 73 (24%) developed neutropenia, 5 (7%) of whom had grade 4 neutropenia (ANC less than 500/mm3). The following were independent predictors for neutropenia: Child-Turcotte-Pugh score (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.02, 1.28; p=0.02), BSI (HR 2.89; 95% CI 1.64, 5.11; p=<0.001), CMV disease (HR 4.28; 95% CI 1.55, 11.8; p=0.005), baseline tacrolimus trough level (HR 1.02; 95% CI 1.01, 1.03; p=0.007) and later era LT (2004–2009 versus 1999–2003) (HR 2.28; 95% CI 1.43, 3.65; p=<0.001). Moreover, neutropenia was found to be an independent predictor for mortality within the first year of LT (HR 3.76; 95% CI 1.84, 7.68; p= <0.001).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that neutropenia within a year after LT is not unusual and is an important predictor of mortality.

Keywords: liver transplantation, neutropenia, valganciclovir, mortality

Introduction

Neutropenia is a serious complication after solid organ transplantation (SOT). The degree and duration of neutropenia contribute to one’s risk of post-SOT infection (1). Advances in immunosuppressive strategies after SOT have led to remarkable improvements in short and long term graft survival (2). However, neutropenia as a consequence of immunosuppressive regimens has recently become more recognized (3, 4). Several medications commonly used post-SOT have been linked to the development of neutropenia, including mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), azathioprine (AZA), antithymocyte globulin for induction (ATG), valganciclovir (VGAN), trimethoprim – sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) and sirolimus (4–7).

Few studies, however, have examined other risks for or outcomes associated with neutropenia after SOT (3, 4, 8). One small study found that body mass index, Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score and baseline leukocyte count were associated with the development of leukopenia and/or neutropenia after orthotopic liver transplantation (LT) (8).

Occurrence of neutropenia usually results in reducing or changing the immunosuppressive regimen which, in turn, might affect graft survival (9, 10). In support of this, data from a large administrative database revealed that the incidence of neutropenia post-renal transplant was 14.5% and was associated with an increased risk of allograft loss and death (11).

The objective of this study was to characterize the incidence and predictors of neutropenia within the first year of LT. Furthermore, we analyzed the relationships between the development of neutropenia within the first year after LT and the clinical outcomes of rejection, infection and death.

Material and Methods

Patient Population

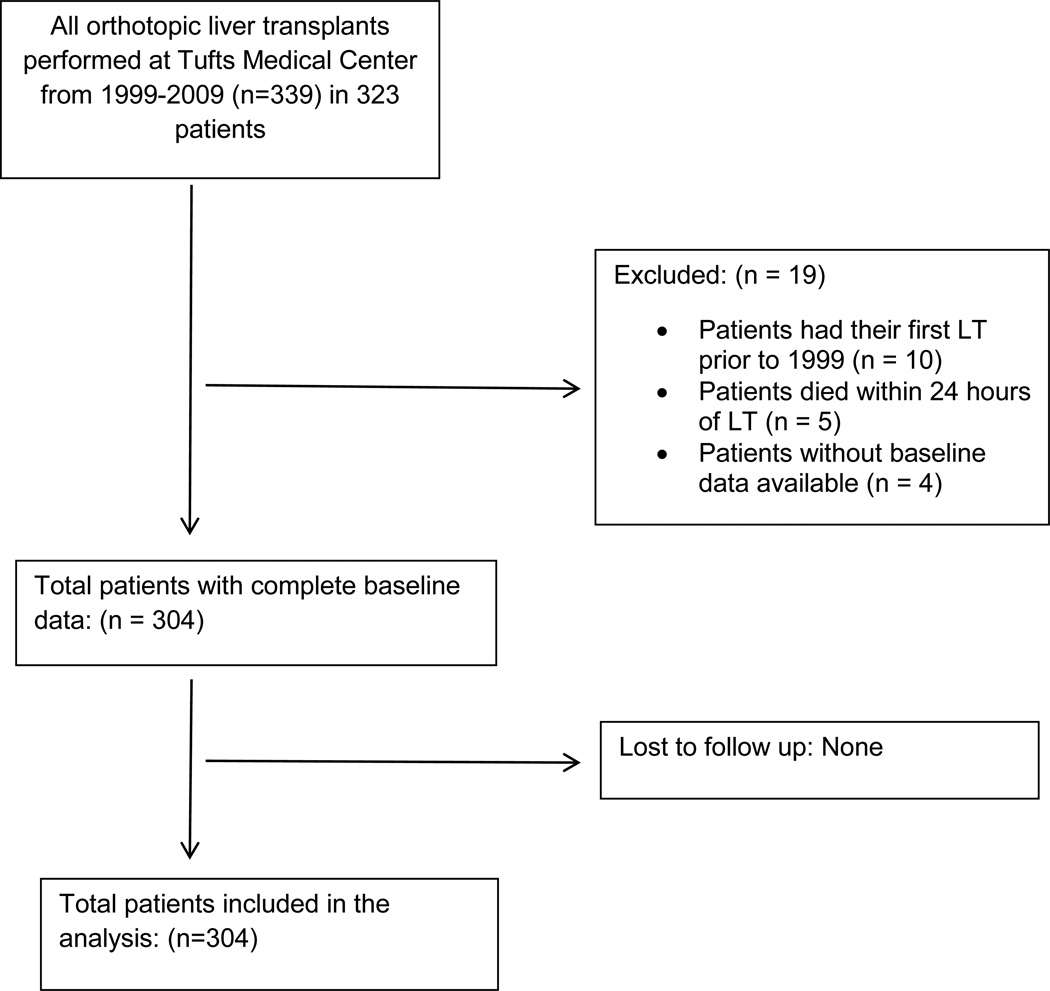

Data from consecutive adult and pediatric patients who underwent LT at Tufts Medical Center from January 1, 1999 – December 31, 2009 were reviewed, including demographics, comorbidities, etiology of underlying liver disease, immunosuppressive regimens, Cytomegalovirus (CMV) prophylaxis and complete pre-transplant baseline laboratory values. Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was recorded from routine follow-up visits for the first year after LT. Occurrence of the following events was captured during the first year after LT: CMV disease, blood stream infection (BSI), invasive fungal infection (IFI), rejection and death. Patients were eligible for inclusion in our study if they met the following criteria: survival of at least 24 hours after LT, availability of a complete data set of pre-defined variables including baseline laboratory values at least 24 hours prior to LT, and post-LT minimum follow-up time of one year or time to death if before one year. Patients whose first LT was prior to 1999 were excluded from this study (Figure 1). Patients with multiple LTs within the study period had their data censored at the time of the second LT.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of inclusion criteria for study population

Definitions

Neutropenia

Grades of neutropenia were defined using the National Cancer Institute Toxicity Criteria: ANC value: 1500–2000/mm3 (grade 1), 1000–1499/mm3 (grade 2), 500–999/mm3 (grade 3) and <500/mm3 (grade 4) (12). Neutropenia was defined as ANC ≤ 1000 mm3 within the first year post-LT. Our institution followed a standard approach to managing neutropenia in our LT recipients. First the dose of TMP-SMX was reduced or an alternate prophylaxis was instituted. If neutropenia persisted, the MMF dose was reduced and GCSF was administered. Finally, if the ANC did not recover, discontinuation of VGAN and replacement with CMVIG was considered.

Severity of Liver Disease

Severity of liver disease was described using laboratory-derived MELD scores. We did not include exception points. Patients who were designated Status 1 for acute fulminant hepatic failure were assigned a MELD score equal to the highest value among our patients (13).

Portal Hypertension

Severity of cirrhosis and portal hypertension were described using Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) scores. Pre-LT status of encephalopathy and ascites and serum albumin, total bilirubin and international normalized ratio (INR) laboratory values closest to but preceding the time of LT were used (14).

Liver Transplant Era

Due to a definitive shift in immunosuppression protocols at our institution (from azathioprine [AZA] to mycophenolate mofetil [MMF]) and in CMV prophylaxis (ganciclovir and CMVIG to VGAN), the early LT era is defined as 1999–2003 whereas the late LT era was from 2004–2009.

Donor Risk Index

The donor risk index (DRI) was calculated according to the method of Feng using a model that incorporates donor age, race, height, cause of death, donation after cardiac death, use of split or partial grafts, location of donor relative to the recipient and cold ischemic time (15).

Immunosuppression

Most patients received an MMF-based induction and maintenance regimen that included MMF, a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus [FK] or cyclosporine [CSA]), and corticosteroids. The second most common induction and maintenance immunosuppressive regimen was an AZA-based regimen that included AZA, a calcineurin inhibitor (FK or CSA), and corticosteroids. Few patients received non-MMF, non-AZA-based immunosuppressive combinations with drugs such as sirolimus. Corticosteroids were tapered off 6 months after LT and AZA or MMF was continued for the entire first year after LT. Baseline immunosuppression was defined at the time of discharge from LT hospitalization as either MMF-based, AZA-based, or neither. Patients who were on hemodialysis pre-LT or who were anticipated to need hemodialysis after LT received ATG during induction in lieu of FK with the addition of FK a few days after LT. Baseline FK or CSA trough level was defined as the drug trough closest to the time of discharge from LT hospitalization but prior to development of the outcomes of neutropenia or mortality. Given the lack of established methods to directly compare FK levels to CSA levels, everyone on CSA (n=31) was set to an FK level of zero in the multivariable survival analysis. By one year after LT, doses of FK were adjusted to achieve a goal trough of 5 ng/mL and doses of CSA were adjusted to achieve a goal trough of 100–200 mcg/L. Methylprednisolone and ATG used for treatment of rejection were modeled as time-dependent variables.

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis

Our institution utilized universal prophylaxis. For CMV prophylaxis, from 1999 until 2003, all at risk patients received 90 days of oral ganciclovir (one gram three times daily or the appropriate dose adjusted for impaired renal function). CMV donor negative to recipient negative patients received 90 days of acyclovir. Any recipient who was CMV positive and/or received an organ from a CMV positive donor also received CMVIG monthly for the first 120 days after LT. After 2004, all patients received IV ganciclovir (5 mg/kg/24 hours or the appropriate dose adjusted for impaired renal function) until able to tolerate oral medications, which was usually within 2–3 days after LT. This was followed by 90 to 120 days (longer in high risk CMV donor positive/recipient negative patients) of oral valganciclovir (900 mg once daily or the appropriate dose adjusted for impaired renal function). CMVIG was not routinely used. Our standard Pneumocystis jiroveci (PCP) prophylaxis was TMP-SMX for 6 months. If the patient was intolerant to TMP-SMX, dapsone was used.

Cytomegalovirus Disease

CMV disease was defined as laboratory and/or pathological confirmation of the presence of CMV in a patient with clinical evidence of organ dysfunction (16).

Blood Stream Infection

BSI was defined as positive blood cultures. Bacteremia caused by common skin contaminants was considered significant if the same organism was isolated from two blood cultures in the presence of clinical signs of infection (17).

Invasive Fungal Infection

IFI was defined as identification of fungal or yeast species by culture or histological examination from a normally sterile site (18). Solitary sputum, urine or T-tube positive cultures were not considered an IFI.

Rejection

Acute rejection was defined by histological evidence of endotheliitis with expansion of portal tracts with mononuclear cells and infiltration and swelling of bile ducts (17).

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used to assess the associations between neutropenia and the outcomes of infection, rejection and death within the first year post-LT regardless of timing. Univariate survival models were generated and all variables with a p-value<0.10 were included in the multivariable models. Backward selection survival analysis was used to test the candidate variables, with a p<0.05 criterion for entry into the final multivariable neutropenia model. Given that there were only 39 deaths, a significance level of <0.005 was used for the mortality backwards selection model to ensure that 4 or fewer variables entered the model to avoid over fitting. In the first multivariable model, neutropenia was the outcome. The time-dependent covariates that may have occurred before neutropenia included rejection, treatment of rejection with ATG and/or methylprednisolone, BSI, CMV, and IFI. In all analyses, only the time to first rejection, first BSI, first CMV and first IFI episode were included. Data were censored at the end of the one-year study period or at the time of death if it occurred before one year. In the second multivariable model, mortality was the outcome, while neutropenia, rejection, treatment of rejection with ATG and/or methylprednisolone, BSI, CMV, and IFI were time-dependent covariates. In this mortality model, infections may have occurred either before or after the onset of neutropenia. Data were censored at end of the study period or at time of death.

In addition, we constructed univariate models assessing the association between the outcome of CMV, IFI, BSI or rejection and neutropenia treated as a time-dependent predictor. In these models, neutropenia occurred before any infections. Data were censored at time of death or end of the study period. All tests were two-sided and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform all analyses. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board at Tufts Medical Center.

Results

Patients

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 339 LTs were performed during the study period in 323 patients. Of these, 304 patients were included in our analysis. Patients were excluded according to criteria described in our methods and as depicted in Figure 1. In our cohort of 304 patients, nine were Status 1 for etiologies related to acute liver failure. Six of these 9 were transplanted for fulminant hepatic failure secondary to toxin ingestion. Some patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and a few patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis as reasons for transplant were not concurrently classified as having cirrhosis.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

|

Characteristic |

Overall population (N=304) (%) |

Neutropenia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=73) (% of overall population) |

No (N=231) (% of overall population) |

P value | ||

| Age at LT (mean years +/− std dev) | 49.3 +/− 13.6 | 49.5 +/− 12.7 | 49.1 +/− 15.1 | 0.55 |

| Male | 205 (67) | 45 (15) | 160 (53) | 0.23 |

| White race | 261 (86) | 61 (20) | 200 (66) | 0.52 |

| Late transplant era: 2004–2009 (versus 1999–2003) | 112 (37) | 39 (13) | 73 (24) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 52 (17) | 9 (3) | 43 (14) | 0.21 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 76 (25) | 17 (6) | 59 (19) | 0.70 |

| Pre-LT baseline eGFR mL/min/1.73 m2, median (IQR)* | 85 (49–103) | 75 (41–100) | 88 (54–105) | 0.05 |

| Underlying Liver Disease | ||||

| Viral hepatitis | 121 (40) | 27 (9) | 94 (31) | 0.57 |

| Alcohol | 94 (1) | 24 (8) | 70 (23) | 0.68 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 76 (25) | 17 (6) | 59 (19) | 0.70 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 24 (8) | 8 (3) | 16 (5) | 0.27 |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 38 (13) | 7 (2) | 31 (10) | 0.39 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 12 (4) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | 0.95 |

| Cirrhosis | 265 (87) | 65 (21) | 200 (66) | 0.58 |

| Status 1 | 9 (3) | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.51 |

| MELD (mean +/− std dev) | 25 +/− 9 | 27 +/− 9 | 24 +/− 9 | 0.01 |

| CTP score (mean +/− std dev) | 9.7 +/− 2.1 | 10.1 +/− 1.9 | 9.6 +/− 2.1 | 0.05 |

| Pre-LT baseline WBC (mean +/− std dev) dev) | 5.93 +/− 3.27 | 5.41 +/− 3.14 | 6.16 +/− 3.50 | 0.10 |

| High risk CMV serology (D+/R−) | 68 (22) | 23(8) | 45(15) | 0.03 |

| Living related donor | 40 (13) | 7 (2) | 33(11) | 0.30 |

| ATG induction | 24 (8) | 10(3) | 14(5) | 0.04 |

| Valganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis | 170 (56) | 49 (16) | 121(40) | 0.03 |

| Ganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis | 132 (43) | 24(8) | 108(36) | 0.04 |

| Initial Immunosuppression Regimen | ||||

| MMF based | 221 (73) | 48 (16) | 173 (57) | 0.15 |

| AZA based | 37 (12) | 7 (2) | 30 (10) | 0.45 |

| Baseline trough drug level** | ||||

| Cyclosporine (mean +/− std dev), N=31 | 237 +/− 87 | 195 +/− 72 | 251 +/− 89 | 0.12 |

| Tacrolimus (median, IQR), N=267 | 8.9 (6.9–10.7) | 8.6 (6.4–10.4) | 9.0 (7.0–10.7) | 0.48 |

| Use of GCSF | 18 (6) | 18 (25) | 0 | N/A |

| Donor Risk Index (median, IQR) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.22 |

eGFR calculated using CKD-EPI equation (20).

Baseline trough level is defined at time of discharge from transplant hospitalization.

Abbreviations: LT, liver transplantation; std dev, standard deviation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; MELD, Model for End Stage Liver Disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; WBC, white blood cell; CMV, cytomegalovirus; D+/R−, CMV-positive donor/CMV-negative recipient; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil; AZA, azathioprine; GCSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor.

Characteristics of Neutropenia After Liver Transplantation

During the first year after LT, 73 of the 304 (24%) LT recipients developed neutropenia. Of these 73 patients, 17 (23%) developed grade 2 neutropenia (6% of total population), 51 (70%) developed grade 3 neutropenia (17% of total population) and 5 (7%) developed grade 4 neutropenia (2% of total population). The median time to the development of the first neutropenia was 74 days (IQR 27–138 days). The duration of neutropenia for the 71 patients (97%) on whom data was available was 3 days (IQR 1–112 days). A total of 18 patients with neutropenia were treated with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) in the first year of LT.

Predictors of Neutropenia

Univariate and multivariable predictors of neutropenia are summarized in Table 2. Late LT era (2004–2009), MELD score, CTP score, ATG for induction, baseline FK trough level, non-MMF and non-AZA-based baseline immunosuppression, valganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis, CMV disease and BSI were significant predictors of neutropenia in univariate analysis. IFI had a trend toward significance. Treatment for rejection with either ATG or methylprednisolone, baseline ANC and eGFR (both as continuous variables) and non-white race were not significant predictors. In the adjusted multivariable analysis, late LT era, CTP score, baseline FK trough level, CMV disease and BSI remained significant independent predictors of neutropenia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariable predictors for neutropenia in the first year after LT

| Characteristic | Univariate | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age at transplant (in decades) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.83 | -- | -- |

| Male gender | 0.75 (0.47, 1.20) | 0.23 | -- | -- |

| White race | 0.80 (0.43, 1.48) | 0.48 | -- | -- |

| Late Era LT (2004–2009) | 2.18 (1.38, 3.45) | 0.001 | 2.28 (1.43, 3.65) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 0.66 (0.33, 1.32) | 0.24 | -- | -- |

| eGFR at pre-LT baseline* | 0.995 (0.990,1.001) | 0.13 | -- | -- |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.90 (0.52, 1.55) | 0.70 | -- | -- |

| Underlying Liver Disease | ||||

| Viral hepatitis | 0.85 (0.53, 1.35) | 0.48 | -- | -- |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.84 (0.49, 1.45) | 0.54 | -- | -- |

| Alcohol | 1.12 (0.69, 1.83) | 0.64 | -- | -- |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1.45 (0.70, 3.03) | 0.32 | -- | -- |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 0.73 (0.34, 1.60) | 0.44 | -- | -- |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1.39 (0.44, 4.42) | 0.58 | -- | -- |

| Status 1 | 1.44 (0.66, 3.14) | 0.36 | -- | -- |

| MELD score | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 0.008 | -- | -- |

| CTP score | 1.14 (1.02, 1.30) | 0.02 | 1.15 (1.03, 1.30) | 0.02 |

| DRI | 1.28 (0.70, 2.31) | 0.43 | -- | -- |

| Pre-LT baseline ANC | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 0.19 | -- | -- |

| Pre-LT baseline WBC | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) | 0.13 | -- | -- |

| Living related donor | 0.66 (0.30, 1.44) | 0.30 | -- | -- |

| ATG for induction | 2.60 (1.33, 5.07) | 0.005 | -- | -- |

| Valganciclovir for CMV prophylaxis | 1.64 (1.00, 2.65) | 0.05 | -- | -- |

| Initial Immunosuppression | ||||

| MMF-based (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| AZA-based | 0.89 (0.40, 1.96) | 0.77 | -- | -- |

| Neither | 2.21 (1.27, 3.84) | 0.005 | -- | -- |

| Tacrolimus baseline trough level** | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 0.007 |

| ATG for rejection | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 0.20 | -- | -- |

| Methylprednisolone for rejection | 0.99 (0.90, 1.10) | 0.85 | -- | -- |

| Rejection | 0.86 (0.51, 1.47) | 0.59 | -- | -- |

| Invasive fungal infection | 1.91 (0.91, 4.02) | 0.09 | -- | -- |

| Blood stream infection | 2.78 (1.58, 4.89) | <0.001 | 2.89 (1.63, 5.11) | <0.001 |

| CMV disease | 5.36 (1.99, 14.42) | <0.001 | 4.28 (1.55, 11.81) | 0.005 |

eGFR calculated using CKD-EPI equation (20).

Baseline trough level is defined at time of discharge from transplant hospitalization.

The following variables were treated as time-dependent covariates: rejection, IFI, BSI, CMV disease, ATG for rejection, methylprednisolone for rejection. All variables with a p-value ≤ 0.10 on univariate testing were entered into the multivariable model.

Abbreviations: LT, liver transplantation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MELD, Model for End Stage Liver Disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; DRI, Donor Risk Index; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; WBC, white blood cell; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil; AZA, azathioprine.

Grades of Neutropenia

We also examined different ANC cutoffs for the definition of the neutropenia outcome. When ANC<750/mm3 and ANC<500/mm3 were used as the neutropenia outcomes, the results of the neutropenia and mortality multivariable models were similar (data not shown).

Mortality

Univariate analysis showed that the development of neutropenia was a significant predictor of mortality in the first year after LT (HR 6.27 95% CI 3.19, 12.34; p<0.001). In the multivariable model, neutropenia remained a significant predictor of mortality (HR 3.76; 95% CI 1.84, 7.68; p<0.001). Other independent predictors included BSI (HR 4.96 95% CI 2.49, 9.89; p<0.001), and CMV disease (HR 5.65; 95%CI 1.99, 16.04; p=0.001). In this model, BSI and CMV disease events may have occurred either before or after the onset of neutropenia. DRI, MELD score, CTP score, Status 1, administration of GCSF, baseline trough levels of CSA or FK, treatment of rejection with methylprednisolone and/or ATG, baseline MMF-based versus AZA-based immunosuppression, and IFI were not significant predictors in the final multivariable mortality model.

Other Complications of Neutropenia

Table 3 shows infectious and rejection outcomes during the first year after LT among the overall population stratified by occurrence of neutropenia regardless of timing of events. Most BSI occurred within 2 months before or after the onset of neutropenia (data not shown). In the first year post-LT when infectious outcomes were restricted to events that occurred after the onset of neutropenia, there was a significant association between neutropenia and increased risk of BSI (HR 3.75; 95% CI 2.03, 6.94; p=<0.001). However, there was no significant association between neutropenia and risk of IFI (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.16, 2.95; p= 0.61), CMV disease (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.40, 2.79; p= 0.91) or rejection (HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.52, 2.16; p= 0.85).

Table 3.

Outcomes in overall population in the first year after LT

| Outcome | Overall population (N= 304) (%) |

Neutropenia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=73) (% of overall population) |

No (N= 231) (% of overall population) |

P value | ||

| Blood stream infection | 68 (22) | 29 (9) | 39 (13) | <0.001 |

| Invasive fungal infection | 33 (11) | 10 (3) | 23 (8) | 0.37 |

| CMV disease | 28 (9) | 10 (3) | 18 (6) | 0.13 |

| Rejection | 120 (39) | 28 (9) | 92 (30) | 0.82 |

| Death | 39 (13) | 17 (6) | 22 (7) | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that neutropenia is a common problem following LT, occurring in almost one quarter of our total population. We identified five factors independently associated with the development of neutropenia after LT: late era transplantation, baseline FK trough level, CTP scores, BSI, and CMV disease. BSI and CMV disease are novel predictors. While it is widely accepted that neutropenia in any host is a risk factor for the development of serious invasive infections including BSI and invasive viral and fungal infections, we are unaware of other studies showing the relationship between these invasive infections and the subsequent development of neutropenia as shown in our time-dependent survival analysis.

Using FK levels, modeled as a continuous variable from trough levels collected at the time of discharge from first transplant surgery hospitalization, we found that higher levels were a significant univariate and multivariable predictor for subsequent neutropenia within the first year of LT. Other studies have also found a relationship between the occurrence of neutropenia and exposure to FK as a categorical variable at time of discharge or at baseline compared to CSA (3, 11). Our study adds to this relationship between FK and neutropenia by finding higher serum FK levels to be an independent predictor for neutropenia. This association might be explained by the increase in MMF bioavailability that results from its pharmacokinetic interaction with FK. One could postulate that this increase in bone marrow MMF exposure in patients with higher FK levels could lead to an association with increased neutropenia (3). Although our study did not include MMF drug levels, future investigations of the interactions among MMF levels, FK levels, and neutropenia should be considered.

We also found an association between having a later era transplant (after 2004) compared with a transplant during the earlier era (1999–2003) and the development of neutropenia. There have been a number of management practices which have changed over time. Prior to 2004, 37 of the 192 patients were on AZA (16%) compared to 118 (62%) on MMF. In the later era, none were on AZA (0%) versus 103 of 112 patients (93%) who were on MMF. Regardless, use of AZA or MMF did not show an independent relationship to neutropenia. Another known difference in management in the later era was use of valganciclovir for 3 to 6 months instead of oral ganciclovir for 3 months plus CMVIG. VGAN exposure did demonstrate a trend towards significance as a predictor for neutropenia, but did not enter the final multivariable model. Although we do not have a definitive explanation for the different risk of neutropenia in the two eras, there is the possibility it is related to the later era use of more intense overall immunosuppressive regimens, the transplantation of more severely ill patients, or the use of marginal donors requiring more intense immunosuppression. In support of this hypothesis, the median MELD score in our study was lower during the early era (21, [IQR: 15–29]) compared to the later era (28, [IQR: 25–31]), p = <0.0001. Also, the median DRI was lower during the early era (1.2, [IQR: 0.9–1.6]) compared to the later era (1.5, [IQR: 1.0–1.6]), p=0.12.

Although it has previously been shown that black race is known to be associated with neutropenia, our study did not find such a relationship between race and neutropenia. However the majority of the LT patients in our study where white (85%) which might have obscured a relationship between black race and neutropenia after LT.

A novel and important finding of our study was the increased risk of death during the first year after LT in patients who developed neutropenia. The increased risk of death in the neutropenia group was independent of other risk factors of mortality including BSI and CMV. One prior study showed that neutropenia was associated with increased mortality after renal transplantation (11). To our knowledge, no studies have looked at this association in LT patients. Both methylprednisolone and ATG were individual significant univariate predictors of death although they were not associated with an increased risk of neutropenia. Baseline FK trough level was also a significant univariate predictor for death. However, none of these immunosuppression variables entered the final multivariable mortality model. Approximately half of the mortality events occurred within two weeks of the time of onset of neutropenia. The relationship between neutropenia and adverse outcomes may not have a direct cause and effect, but rather, neutropenia may be serving as a marker for other factors that more directly contribute mortality.

Another important finding of our study was the increased risk of BSI that occurred after neutropenia in the first year after LT. The majority of first BSI (78%) events occurred at a median time of 31 days (IQR 9–153 days) while patients were still receiving TMP-SMX prophylaxis. This suggests that development of BSI was not related to discontinuation of PCP prophylaxis.

We used MELD scores as a continuous variable to define severity of liver disease, and also included Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) scores as a continuous variable to evaluate the relationship between cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension and the outcomes of neutropenia and mortality. In patients with cirrhosis, leukopenia was found to be a predictor of death or LT after adjusting for CTP scores (19). Residual hypersplenism after LT in patients with pre-LT portal hypertension could also contribute to a lower WBC after LT, however other factors in our study also independently contributed to the risk for neutropenia. Although CTP score was associated with increased mortality on univariate analysis, it was not an independent predictor of death unlike neutropenia itself, which had an independent association with increased mortality.

Our study has several strengths including the use of survival models employing time-dependent covariates. This method allowed us to more precisely study the association between the occurrence of neutropenia and mortality in relation to other time-varying events such as rejection, rejection treatment (ATG and/or pulse steroids) and several types of invasive infections. We also evaluated maintenance level of FK or CSA at the time of discharge from transplant surgery, in addition to several other important potential confounding variables as potential predictors of neutropenia and death. Knowledge of each patient’s calcineurin inhibitor level, rather than simply the type of immunosuppressive regimen, provides enhanced information on the impact of the degree of immunosuppression from these medications on patient outcomes and survival. To further support our findings on the relationship between potential predictors of post-LT neutropenia and our outcomes, we used the grades of neutropenia severity as cut offs for our definition of neutropenia. When the cut off was changed to an ANC of either 750/mm3 (grade 3) or 500/mm3 (grade 4), similar results were obtained, although CTP score was no longer statistically significant. This is likely due to the reduced number of neutropenia outcomes with each definition and reduced power to detect differences. The risk associated with CMV disease increased with lower ANC, which could affect clinical practice and CMV screening and/or preemptive treatment protocols. The median duration of neutropenia was 3 days with a range of 1 to 112 days. It is notable that despite this relatively short duration of neutropenia, the impact of neutropenia remained associated with poor outcomes. Though we cannot determine a causal relationship between neutropenia and infection or mortality from our analysis, neutropenia may be serving as a marker for unknown or unmeasured confounders for these adverse outcomes.

Despite these strengths in methods and statistical analysis, there are some limitations worthy of noting. This is a single center study, and it is retrospective over a 10-year time span, during which surgical technique, clinical management, and immunosuppressive regimens of LT recipients have evolved. Since our study was designed to predict neutropenia specifically in LT recipients, the results may not be generalizable to other types of SOT, transplant patient populations using different medications, or transplant centers that employ two-drug or one-drug immunosuppressive regimens compared to our three-drug standard regimen with maintenance goal FK troughs of 5 ng/mL and goal CSA troughs of 100–200 mcg/L. We also did not model FK and CSA levels or renal dysfunction at the time of development of neutropenia, both of which could be important potential confounders. We know that higher immunosuppression might lead to an increase in neutropenia and more renal dysfunction, which is associated with post-transplant infection and mortality (19). In order to model calcineurin inhibitor levels and renal function as time-dependent variables, one would need to collect frequent measurements of both variables for the entire study period which would be logistically difficult, especially in the outpatient setting. Two previous studies of neutropenia in renal transplantation were also not able to examine these confounders in a time-dependent manner (3, 11). We did, however, examine baseline creatinine and eGFR (Table 2) as continuous variables and they did not differ between neutropenic and non-neutropenic patients. When neutropenia was investigated as a potential predictor of the outcomes of death, rejection, and different infections, neutropenia was treated as a time-dependent covariate with respect to timing after LT, but not duration of occurrence. This is a limitation that could have an impact on the relationship between neutropenia and different outcomes after LT.

In conclusion, we found that neutropenia is common within the first year after LT and is associated with later era transplantation, baseline FK trough level, CTP scores, as well as BSI and CMV disease. Patients who developed neutropenia are at increased risk of death and BSI in the first year after LT. Future studies should be directed toward measures to prevent or promptly treat neutropenia in this population to determine if this improves the associated adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank and acknowledge the help of our transplant surgery coordinator, Karen Curreri, RN, as well as our infectious disease study coordinators: Lauren Verra, BS, Lauren Nadkarni, BS, and Abigail Benudis, BS.

Financial Support

Funding for this research project was supported by the National Institutes of Health Training Grants: 5T32 AI007329-19 (N.N), 5T32 AI055412-05 (N.N), K23 DK083504 (J.C) and the Ministry of Higher Education in Saudi Arabia (B.A).

This study was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources Grant Number UL1 RR025752, now the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Grant Number UL1 TR000073 (LLP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Dr. Snydman has been a consultant for CSL Behring, Merck, Genentech, Millenium, Genzyme, Massachusetts Biologic public Health Laboratories, Microbiotix and Boeringer-Ingelheim; has received grant support from Merck, Pfizer, Optimer, Cubist, Forrest, Replidyne, Astra Zeneca and Genentech; and has received honoraria from Merck, Cubist and Genentech.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Absolute neutrophil count

- ATG

Antithymocyte globulin

- AZA

Azathioprine

- BSI

Blood stream infection

- CTP

Child Turcotte Pugh

- CI

Confidence interval

- CSA

Cyclosporine

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CMVIG

Cytomegalovirus immune globulin

- DRI

Donor Risk Index

- eGFR

Estimated Glomerular filtration rate

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IQR

Interquartile range

- IFI

Invasive fungal infection

- LT

Liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End Stage Liver Disease

- MMF

Mycophenolate mofetil

- PCP

Pneumocystis jiroveci

- SOT

Solid organ transplantation

- FK

Tacrolimus

- TMP-SMX

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

- WBC

White blood cell

- VGAN

Valganciclovir

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All other authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

This study was presented at the 52nd Annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC), September 2012 in San Francisco, California.

Reference

- 1.Bodey GP, Buckley M, Sathe YS, Freireich EJ. Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Annals of internal medicine. 1966;64(2):328–340. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-64-2-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariharan S, Johnson CP, Bresnahan BA, Taranto SE, McIntosh MJ, Stablein D. Improved graft survival after renal transplantation in the United States, 1988 to 1996. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;342(9):605–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zafrani L, Truffaut L, Kreis H, Etienne D, Rafat C, Lechaton S, et al. Incidence, risk factors and clinical consequences of neutropenia following kidney transplantation: a retrospective study. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9(8):1816–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brum S, Nolasco F, Sousa J, Ferreira A, Possante M, Pinto JR, et al. Leukopenia in kidney transplant patients with the association of valganciclovir and mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation proceedings. 2008;40(3):752–754. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keisu M, Wiholm BE, Palmblad J. Trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole-associated blood dyscrasias. Ten years' experience of the Swedish spontaneous reporting system. Journal of internal medicine. 1990;228(4):353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan DC, Daller JA, Lake KD, Cibrik D, Del Castillo D. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin versus basiliximab in renal transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355(19):1967–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong JC, Kahan BD. Sirolimus-induced thrombocytopenia and leukopenia in renal transplant recipients: risk factors, incidence, progression, and management. Transplantation. 2000;69(10):2085–2090. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molina Perez E, Fernandez Castroagudin J, Seijo Rios S, Mera Calvino J, Tome Martinez de Rituerto S, Otero Anton E, et al. Valganciclovir-induced leukopenia in liver transplant recipients: influence of concomitant use of mycophenolate mofetil. Transplantation proceedings. 2009;41(3):1047–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knoll GA, MacDonald I, Khan A, Van Walraven C. Mycophenolate mofetil dose reduction and the risk of acute rejection after renal transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2003;14(9):2381–2386. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000079616.71891.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rerolle JP, Szelag JC, Le Meur Y. Unexpected rate of severe leucopenia with the association of mycophenolate mofetil and valganciclovir in kidney transplant recipients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2007;22(2):671–672. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurst FP, Belur P, Nee R, Agodoa LY, Patel P, Abbott KC, et al. Poor outcomes associated with neutropenia after kidney transplantation: analysis of United States Renal Data System. Transplantation. 2011;92(1):36–40. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821c1e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0. National Cancer Institute; 2009. May 28, [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2001;33(2):464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. The British journal of surgery. 1973;60(8):646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, DebRoy MA, et al. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2006;6(4):783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;34(8):1094–1097. doi: 10.1086/339329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz-Price LS, Slifkin M, Ruthazer R, Poutsiaka DD, Hadley S, Freeman R, et al. The clinical impact of ganciclovir prophylaxis on the occurrence of bacteremia in orthotopic liver transplant recipients. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;39(9):1293–1299. doi: 10.1086/425002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George MJ, Snydman DR, Werner BG, Griffith J, Falagas ME, Dougherty NN, et al. The independent role of cytomegalovirus as a risk factor for invasive fungal disease in orthotopic liver transplant recipients. Boston Center for Liver Transplantation CMVIG-Study Group. Cytogam, MedImmune, Inc. Gaithersburg, Maryland. The American journal of medicine. 1997;103(2):106–113. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qamar AA, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Burroughs AK, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical significance of abnormal hematologic indices in compensated cirrhosis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2009;7(6):689–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]