Abstract

Network meta-analysis expands the scope of a conventional pairwise meta-analysis to simultaneously compare multiple treatments, synthesizing both direct and indirect information and thus strengthening inference. Since most of trials only compare two treatments, a typical data set in a network meta-analysis managed as a trial-by-treatment matrix is extremely sparse, like an incomplete block structure with significant missing data. Zhang et al. proposed an arm-based method accounting for correlations among different treatments within the same trial and assuming that absent arms are missing at random. However, in randomized controlled trials, nonignorable missingness or missingness not at random may occur due to deliberate choices of treatments at the design stage. In addition, those undertaking a network metaanalysis may selectively choose treatments to include in the analysis, which may also lead to missingness not at random. In this paper, we extend our previous work to incorporate missingness not at random using selection models. The proposed method is then applied to two network meta-analyses and evaluated through extensive simulation studies. We also provide comprehensive comparisons of a commonly used contrast-based method and the arm-based method via simulations in a technical appendix under missing completely at random and missing at random.

Keywords: Network meta-analysis, Bayesian hierarchical models, nonignorable missingness, selection models

1 Introduction

Network meta-analysis (NMA, also called mixed or multiple treatment comparisons), a metaanalytic statistical method, expands the scope of a conventional pairwise meta-analysis to simultaneously compare multiple treatments by synthesizing both direct and indirect information. NMA has two major roles. First, it enables us to obtain simultaneous inference regarding all treatments of interest, typically to select the best one or subset. With rapid growth in the number of potential treatments for a given condition, doctors and patients often want to know their population-averaged treatment-specific effects and their relative ranks in terms of safety and efficacy. Second, inference regarding the relative effect of two treatments can be strengthened by borrowing information from indirect comparisons. In the simplest case, one may be interested in comparing two treatments A and B. Direct evidence can only be obtained from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of A versus B, while indirect evidence can be obtained from RCTs of either A or B versus a common comparator C.1 By combining the two sources of information as a weighted average using appropriate statistical methods, more precise estimates of treatment effects than those produced by standard pairwise meta-analysis can be obtained.2 In summary, NMA provides simultaneous comparisons of multiple treatments and more precise treatment effect estimates.3

Commonly, only a subset of treatments of interest (say, two or three) is compared in each trial in an NMA, so that a typical data structure expressed as a trial-by-treatment matrix is extremely sparse. For example, a recent NMA4 published in The Lancet comprised 117 RCTs to compare 12 new-generation antidepressants, where 114 RCTs were two-arm trials and the other 3 RCTs were three-arm trials, leading to an incomplete block structure with significant missing data. Currently, popular contrast-based (CB) NMA statistical methods5–8 only model the observed data, while a recent arm-based (AB) method proposed by Zhang et al.9 assumes only a missing at random (MAR) mechanism and imputes missing components using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms. Thus, CB methods are essentially the classic “available case analysis” for missing data, which may lead to problems when the data are not missing completely at random (MCAR), or when correlations among variables are high.10 Furthermore, they can produce estimated covariance matrices that are implausible, such as estimating correlations outside of the range from −1.0 to 1.0.10,11 The AB method does not bear such risks. In addition, simulation results in the Gaussian data context12 and real data analyses for binary outcomes9 have shown that the effect size estimates by this AB method have smaller biases and narrower credible intervals (CIs) than those provided by CB methods in some cases.

In addition, the AB and CB methods involve different random effect assumptions. Shuster et al.13 distinguished between two random effect assumptions for meta-analysis: studies at random (SR), and effects at random (ER). SR assumes that the studies are independently chosen from a conceptual urn containing a large number of studies, while ER assumes that the effects in each study are randomly drawn from a conceptual urn, but the studies are fixed. ER makes several assumptions that are difficult to verify empirically; e.g., that the distribution of the random effects under ER is independent of study design and baseline risk (where the baseline varies across trials and can be either placebo or active treatments). The AB method requires an SR-type assumption, while the CB method instead requires the ER assumption.

Nonignorable missingness, or missingness not at random (MNAR), caused by deliberate choices of treatments at the trial design stage or selective choices during the process of systematic review and meta-analysis, is a thorny situation for NMA. For example, clinicians often select treatments that appear to be more effective based on previous RCTs or their own personal medical experience,14 which may cause a higher probability of missingness for relatively ineffective treatments. Another situation that can result in nonignorable missingness of treatments is when meta-analysts selectively choose the evidence to be synthesized. For example, some NMAs exclude placebo or no treatment groups from consideration because meta-analysts believe that placebo or no treatment trials may vary over time, or are set in favorable conditions to appease regulatory authorities.15 Other NMAs may include only treatments available in a particular location or time period, or those of perceived dose relevance, or certain specific competing treatments in the case of industry submissions to health technology assessment bodies.15,16 In these cases, simply ignoring missingness (as the CB methods do) or considering all missing data to be MAR (as the standard AB method9 does) may lead to bias.10

The purpose of this paper is to develop methods to incorporate nonignorable missingness. The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. We present our proposed method in Section 2, apply it to the smoking cessation and prevention of pain on injection with Propofol data sets in Section 3, and evaluate its performance through simulation studies in Section 4. Finally, we close with a discussion of our results, several contentious issues, and a few avenues for future research in Section 5. Appendix 1 provides a comprehensive comparison of the AB method in Zhang et al.9 and the CB method in Lu and Ades8 for binary data under MCAR and MAR mechanisms.

2 Statistical method incorporating nonignorable missingness

Nonignorable missingness is inevitable when clinicians selectively include treatments in trials or meta-analysts selectively choose treatments in an NMA. Unfortunately, one can never tell from the data at hand whether the missing treatments are MAR or MNAR.10 The fundamental difficulty is that potential “lurking variables” controlling the missingness are unobserved, and thus we can never rule out MNAR. Rather than trying to test whether the missingness is MAR, we develop a novel method using sensitivity analysis to incorporate nonignorable missingness. Note that even if an assumption of MAR seems reasonable, it is worthwhile to investigate how the results may change under nonignorable missingness.

Suppose an NMA comprises I RCTs to compare K treatments of interest. Let i = 1, 2, …, I index the trials and k = 1, …, K index the treatments. Let Si be the set of treatments that are compared in the i-th trial and Ci be its cardinality. Trials with Ci ≥ 3 are called “multi-arm” trials, in contrast to Ci = 2 for “two-arm” trials. In this paper, we only focus on the binary data case, but our method can be easily extended to other types of data. We let yobsi = (yik, nik), k ∈ Si and ymisi = (yik, nik), k ∉ Si denote the observed data and missing data from the i-th trial, where nik is the total number of subjects and yik is the number of responses for the k-th treatment in the i-th trial. The corresponding probability of response is denoted by pik. Then we let Yobs = (yobs1, …, yobsI) and Ymis = (ymis1, …, ymisI) denote the full collections of the observed and missing data.

Let R be a corresponding I × K indicator matrix of missingness with (i, k)-entry rik, where rik = 0 if yik is observed and rik = 1 if yik is missing. (Yobs, Ymis, R) and (Yobs, R) denote the complete and observed data, respectively. The practical implication of MNAR is that the likelihood requires an explicit model for R. Selection models, introduced by Heckman,17 provides a way to do this. Here, we factor the joint distribution of the complete data and the missingness indicators into a marginal density for the complete data and a conditional density for the missingness indicators given the complete data, i.e., f(Yobs, Ymis, R|θ, α) = f(Yobs, Ymis|θ, α) f(R|Yobs, Ymis, θ, α), where θ is the set of parameters of interest and α is the set of parameters for the missingness mechanism. This factorization can usually be simplified to f(Yobs, Ymis, R|θ, α) = f(Yobs, Ymis|θ) f(R|Yobs, Ymis, α), if Yobs, Ymis|θ is conditionally independent of α, and R|Yobs, Ymis, α is conditionally independent of θ, which is usually reasonable in practice. We further call f(Yobs, Ymis|θ) the model of interest (MOI) and f(R|Yobs, Ymis, α) the model of missingness (MOM).18 We first separately specify MOI and MOM, and then combine them into a single joint statistical model.

2.1 Various MOIs

Following Zhang et al.,9 multivariate generalized linear mixed models (MGLMMs) are often used for the MOI. The number of responses yik is assumed to have an independent binomial distribution with probability pik, i.e., yik ~ Bin(nik, pik), while pik on a transformed scale, i.e., g(pik), is assumed to have a multivariate normal distribution. Here, g() is some appropriate link function; we prefer the probit link Φ−1() because it enables a closed form for the population-averaged event rate,9 while the canonical logit link does not. Thus, the model is parameterized as follows

| (1) |

where μk is the fixed effect and νik is the random effect for the k-th treatment in the i-th trial, and (νi1, … νiK) is a vector of all random effects in the i-th trial with covariance matrix Σk.

A possible factorization of ΣK is ΣK = diag(σ1, …, σK) × ΩK × diag(σ1, …, σK), where ΩK is a positive definite correlation matrix, and diag(σ1, …, σK) is a diagonal matrix with k-th entry σk representing the standard deviation for the random effects νik. In (1), the trial-level heterogeneity in response to treatment k is captured by σk, and the within-trial dependence among treatments is captured by ΩK. Zhang et al.9 show the population-averaged event rate can be calculated as , where Φ() is the cumulative density function, and ϕ() is the probability density function for the standard normal distribution. As such, marginal effect measures can then be calculated, including the relative risk, RRkl = π;k/πl, risk difference, RDkl = πk − πl, and odds ratio, .

Various MOIs can be proposed according to (1). The simplest model can be specified as Φ−1(pik) = μk + νi with νi ~ N(0, σ2) accounting for heterogeneity across trials. In this case, random effects for different treatments within the same trial are perfectly correlated (a correlation coefficient of 1); we refer to this model as MOI i. MOI i can be extended to allow heterogeneous variances, i.e., Φ−1(pik) = μk + νik with ; this is MOI ii. This model assumes that random effects for different treatments within the same trial are uncorrelated. Another way to extend MOI i is Φ−1(pik) = μk + νik where (νi1, νi2, …, νiK) has an exchangeable correlation matrix with the same correlation parameter ρ and the same variance parameter σ2; we call this model MOI iii. A more general model is Φ−1(pik) = μk + νik with (νi1, νi2, …, νiK) being an exchangeable correlation matrix with the same correlation parameter ρ but different variance parameters for different treatments; this is MOI iv. Finally, the most general model assumes an arbitrary unstructured covariance matrix ΣK, where variances of different treatments are different, and correlations between different pairs of treatments are also different; this is model MOI v. In general, MOI i is simple but may not be practical in most cases, whereas there may not be enough information contained in the data to accurately estimate all the parameters in MOI v when the number of treatments K is large and the number of studies I is small. The exchangeable correlation models MOI iii and MOI iv appear to offer sensible yet practical alternatives.

Since improper prior distributions may lead to improper posteriors in some complex models,19–22 we select minimally informative but proper priors. Specifically, we chose N(0, 1000) priors for μk in all models, Gamma(1, 1) priors for the precisions τ = 1/σ2 in MOI i and in MOI ii (corresponding to a 95% Bayesian CI for variance parameters ranging from 0.27 to 39.5), and U(0, 5) priors for σ and σk and U(0.0001,1) for ρ in MOI iii and MOI iv. A vague Wishart prior is chosen for the precision matrix in the unstructured model MOI v, i.e., , where n=K is the degrees of freedom and V is a known K×K matrix with diagonal elements equal to 0.1 and off-diagonal elements equal to 0.005. It turns out that the above prior corresponds to a 95% Bayesian CI for the variance parameters ranging from 0.02 to 98.93, and a 95% Bayesian CI for the correlation parameters ranging from −1.00 to 1.00 (i.e., fully noninformative).

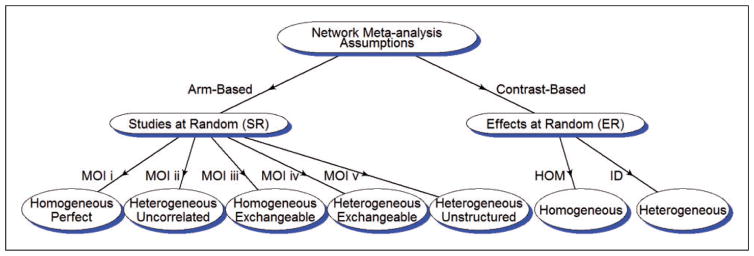

Figure 1 shows various model assumptions for MOI i to MOI v. Each model is labeled near the arrow of the line and the corresponding model assumption is shown in the ellipse. “Homogeneous” and “Heterogeneous” indicate what variances are used for random effects; and “Perfect,” “Uncorrelated,” “Exchangeable,” and “Unstructured” categorize the correlation matrices of random effects. In addition, the aforementioned SR and ER assumptions introduced in Shuster et al.13 are adopted for the AB and CB methods in this diagram. The HOM and ID models are two CB models from Lu and Ades8 that will be used in our simulation studies.

Figure 1.

Diagram of model assumptions. The arm-based method assumes studies at random (SR) while the contrast-based methods assume effects at random (ER). Homogeneous/heterogeneous refer to variances and perfect/exchangeable/unstructured refer to correlation matrices. Perfect refers to a correlation of 1 among random effects for different treatments within the same trial. Finally, HOM and ID are the homogeneous and heterogeneous models in Lu and Ades.8

2.2 MOM specifications

Now we introduce specifications for the MOM. If f(R|Yobs, Ymis, α) = f (R|α), the mechanism is MCAR; if f(R|Yobs, Ymis, α) = f(R|Yobs, α), it is MAR; and if there is no simplification possible for the conditional distribution f(R|Yobs, Ymis, α), it is MNAR.

We assume rik, the missingness indicator for the k-th treatment in the i-th trial, has a Bernoulli distribution with a probability of missingness , i.e., . Under the MNAR mechanism, depends on yik. A common way to realize the above is through linking with the estimated pik (which is approximately ), i.e., , where and h2(pik) are some proper functions of and pik. We here use the canonical logit link for both h1() and h2(). However, we note that a probit link would work equally well; see Appendix 2 for results for the two real data sets under both the logit and probit links. Tables 9 and 10 reveal the results to be broadly similar. Specifically, our MOM is proposed as follows

Table 9.

Posterior medians and their 95% credible intervals for the population-averaged event rates of the four treatments in the smoking cessation data set with different link functions.

| logit

|

probit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JM ii | JM i | JM i | JM ii | |

| πA | 0.09 (0.06,0.12) | 0.09 (0.06,0.13) | 0.09 (0.06,0.13) | 0.09 (0.06,0.12) |

| πB | 0.15 (0.09,0.24) | 0.13 (0.07,0.22) | 0.13 (0.07,0.24) | 0.15 (0.09,0.24) |

| πC | 0.18 (0.14,0.23) | 0.18 (0.14,0.24) | 0.18 (0.14,0.24) | 0.18 (0.14,0.23) |

| πD | 0.22 (0.14,0.34) | 0.20 (0.11,0.33) | 0.21 (0.11,0.34) | 0.22 (0.14,0.34) |

| DICM | 109.2 | 104.1 | 103.7 | 108.7 |

| DICI | 323.1 | 323.2 | 323.2 | 323.0 |

Results from JM i and JM ii are reported. πA–D represent the event rates for Treatments A–D.

Table 10.

Posterior medians and their 95% credible intervals for the population-averaged event rates of the eight treatments in the data set about prevention of pain on injection with Propofol with different link functions.

| logit

|

probit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JM i | JM ii | JM i | JM ii | |

| πA | 0.28 (0.21,0.35) | 0.30 (0.24,0.37) | 0.27 (0.21,0.34) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) |

| πB | 0.49 (0.29,0.65) | 0.38 (0.27,0.50) | 0.50 (0.33,0.65) | 0.37 (0.26,0.49) |

| πC | 0.56 (0.40,0.71) | 0.59 (0.47,0.70) | 0.56 (0.40,0.71) | 0.58 (0.47,0.69) |

| πD | 0.60 (0.46,0.72) | 0.63 (0.54,0.72) | 0.60 (0.46,0.73) | 0.63 (0.53,0.71) |

| πE | 0.85 (0.71,0.93) | 0.80 (0.66,0.90) | 0.85 (0.70,0.93) | 0.80 0.65,0.89 |

| πF | 0.63 (0.46,0.78) | 0.62 (0.51,0.73) | 0.64 (0.47,0.78) | 0.62 (0.50,0.72) |

| πG | 0.61 (0.34,0.86) | 0.70 (0.52,0.85) | 0.57 (0.33,0.82) | 0.69 (0.50,0.84) |

| πH | 0.46 (0.26,0.65) | 0.41 (0.27,0.56) | 0.47 (0.28,0.66) | 0.40 (0.26,0.55) |

| DICM | 333.3 | 366.7 | 333.8 | 367.6 |

| DICI | 574.0 | 573.5 | 568.5 | 569.3 |

Results from JM i and JM ii are reported. πA–H represent the event rates for Treatments A–H.

| (2) |

where α0k is an unknown scalar parameter, and α1k determines the missingness mechanism, i.e., nonignorable missingness if α1k ≠ 0 and ignorable missingness if α1k=0. In this model, the probabilities of missingness for different treatments have different parameters of missingness α1k. We call this model MOM i. A simpler model can be specified as , where all treatments share the same missingness parameter α1. We denote this model by MOM ii.

A flat prior for α0k with a large variance would lead to a marginal prior distribution for that is heavily biased towards 0 and 1. We thus specify a logistic(0, 1) prior for α0k, which corresponds to an approximate uniform prior on (0, 1) for .23 In the same way, a large variance on the prior of α1k can also lead to biased marginal priors for . Thus, we use a weakly informative N(0,0.68) prior for α1k, following Jackson et al.24 and Mason et al.18

Finally, the joint distribution of Yobs and R can be derived by integrating out the Ymis as follows

| (3) |

2.3 Model selection and construction of joint models

The Deviance Information Criterion (DIC)25 was used as the model selection criterion. The deviance, up to an additive quantity not depending upon θ, is D(θ) = −2logL(θ; Data), where L(θ; Data) is the likelihood for the respective model. The DIC is given by , where is the proper mean deviance, and is the effective number of model parameters. It rewards better fitting models through the first term and penalizes more complex models through the second term. A model with smaller overall DIC value is preferred.

All models were implemented via MCMC methods using the WinBUGS software. The convergence of MCMC chains was assessed by the Gelman-Rubin convergence statistic and by visual inspection of the chains. WinBUGS automatically generates DIC estimates for the MOIs and MOMs separately, and we call them DICI (DIC of interest) and DICM (DIC of missingness), respectively. DICI is generated based on the observed data likelihood; while in the construction of DICM, Ymis are treated as extra parameters in the MOMs, with the MOI acting as their prior distribution. Mason et al.18 have suggested the use of DICM to compare the fit of different MOMs with the same MOI. We remark that use of DIC in missing data setting is controversial; see Celeux et al.26

Thus, the construction of the joint models can be summarized as two steps: in the first step, the best MOI with the smallest DICI is chosen from MOI i to MOI v; and in the second step, MOM i and MOM ii are coupled with the best MOI as joint models, named JM i and JM ii. We will select the joint model with the smaller DICM as our final model.

3 Data analysis

3.1 Smoking cessation data

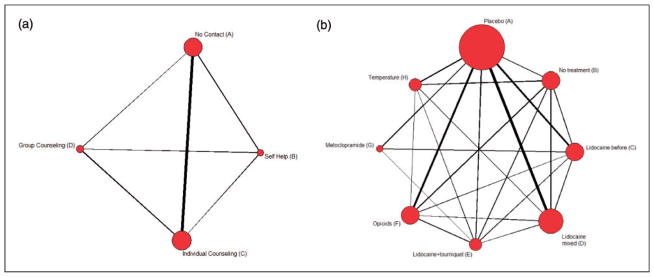

We apply our proposed method in Section 2 to a smoking cessation data set27,28. This data set comprises 24 trials (22 two-arm and 2 three-arm) and 18,822 participants trying to quite smoking using one of the four treatments: (A) no contact, (B) self-help, (C) individual counseling, and (D) group counseling. Figure 2(a) shows an undirected graph elucidating the network of comparative relations for the four treatments, with the size of each node proportional to the frequency of that treatment, and the thickness of the link proportional to the number of trials investigating the pairwise comparison.

Figure 2.

Graphical representations for the networks of the smoking cessation and prevention of pain on injection with Propofol data sets. The size of each node is proportional to the number of trials including the respective intervention, and the thickness of the link is proportional to the numbers of trials investigating the relation.

Table 1 shows the posterior medians of population-averaged event rates (πA, πB, πC, and πD) and their 95% posterior CIs for various models. MOI iii, MOI iv, and MOI v, which assume random effects (νi1, νi2, …, νiK) in the same trial have a multivariate normal distribution, show smaller DICI than MOI i and MOI ii, which assume either perfect or no correlations. While MOI iii, MOI iv, and MOI v get similar DICIs, we selected MOI iii as the best MOI because it is the simplest in parameterization and easiest in implementation.

Table 1.

Posterior medians and their 95% credible intervals for the population-averaged event rates of the four treatments in the smoking cessation data set.

| MOI i | MOI ii | MOI iii | MOI iv | MOI v | JM i | JM ii | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| πA | 0.11 (0.08,0.15) | 0.10 (0.08,0.13) | 0.09 (0.06,0.12) | 0.08 (0.06,0.11) | 0.08 (0.06,0.10) | 0.09 (0.06,0.13) | 0.09 (0.06,0.12) |

| πB | 0.13 (0.09,0.18) | 0.17 (0.11,0.27) | 0.14 (0.09,0.22) | 0.16 (0.09,0.33) | 0.15 (0.09,0.24) | 0.13 (0.07,0.22) | 0.15 (0.09,0.24) |

| πC | 0.18 (0.14,0.24) | 0.25 (0.16,0.39) | 0.18 (0.14,0.23) | 0.18 (0.13,0.24) | 0.17 (0.13,0.23) | 0.18 (0.14,0.24) | 0.18 (0.14,0.23) |

| πD | 0.20 (0.14,0.27) | 0.31 (0.18,0.50) | 0.21 (0.14,0.32) | 0.23 (0.13,0.45) | 0.21 (0.13,0.33) | 0.20 (0.11,0.33) | 0.22 (0.14,0.34) |

| DICM | —– | —– | —– | —– | —– | 104.1 | 109.2 |

| DICI | 545.5 | 374.9 | 323.1 | 325.5 | 324.4 | 323.2 | 323.1 |

πA–D represent the event rates for Treatments A–D. The bold cells highlight the smallest DICs.

Now let us take a look at the results from the joint models. JM i comprises MOI iii and MOM i, and JM ii comprises MOI iii and MOM ii. Table 1 shows that the estimates for the population-averaged event rates πA and πC from JM i and JM ii are exactly the same as MOI iii, while those for πB and πD are slightly different from MOI iii. These subtle differences do not provide convincing evidence of nonignorable missingness. Note that DICM for JM i is smaller than DICM for JM ii, thus MOM i is more suitable for these data than MOM ii. As such, we adopt JM i for all further investigation.

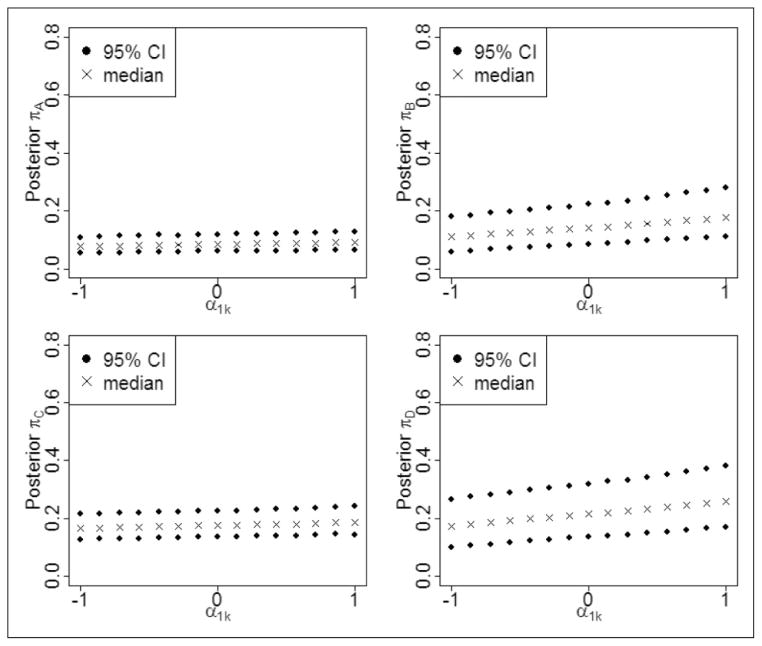

Since the values of α1k control the degree of departure from MAR missingness, we conduct sensitivity analyses in which the changes in the estimated parameters of interest are studied for different values of the missingness parameters α1k. In other words, we carry out a sensitivity analysis where a series of models are run with a set of fixed values for the α1k. More specifically, we use 15 values uniformly distributed between −1 and 1, namely −1.00, −0.86, −0.71, −0.57, −0.43, −0.29, −0.14, 0.00, 0.14, 0.29, 0.43, 0.57, 0.71, 0.86, and 1.00 for α1k. Figure 3 presents the posterior medians and their 95% CIs for the population-averaged response rates versus different values of α1k. Note that πA and πC versus α1k in the left part of Figure 3 are horizontal lines, while πB and πD versus α1k in the right part of Figure 3 have slight slopes. Thus, Treatments B and D seem to be slightly dependent on the missingness parameter α1k, but Treatments A and C are more robust to changes in α1k here. However, we do note that in the smoking cessation data, the numbers of trials that contain Treatments A (19) and C (19) are larger than the numbers of trials containing Treatments B (6) and D (6), which explains at least part of the reason why Treatments B and D are more sensitive to the missingness parameter. In summary, neither Table 1 nor Figure 3 suggests the presence of serious nonignorable missingness.

Figure 3.

Population-averaged event rates variations with changes in α1k. Posterior medians and their 95% credible intervals are presented for the smoking cessation data.

Table 2 presents the odds ratios comparing the four treatments estimated from JM i and JM ii. In JM i, with Treatment A as the baseline treatment, our estimates are ORBA = 1.44 with 95% CI (0.67, 3.01), ORCA = 2.20 with 95% CI (1.42, 3.44), and ORDA = 2.44 with 95% CI (1.11, 5.29). Thus Treatments C (individual counseling) and D (group counseling) are significantly more effective than A (no contact) for smoking cessation, while Treatment B (self-help) is not significantly different from A. We draw the same basic conclusions regarding statistical significance from JM ii, though the magnitudes of the estimated ORs are slightly different.

Table 2.

Posterior medians of ORs estimated from JM i and JM ii with their 95% credible intervals for the smoking cessation data set.

| ORBA | ORCA | ORDA | ORCB | ORDB | ORDC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JM i | 1.44 (0.67,3.01) | 2.20 (1.42,3.44) | 2.44 (1.11,5.29) | 1.53 (0.76,3.33) | 1.70 (0.71,4.26) | 1.11 (0.53,2.32) |

| JM ii | 1.83 (0.95,3.51) | 2.26 (1.49,3.44) | 2.98 (1.55,5.80) | 1.23 (0.66,2.36) | 1.63 (0.78,3.40) | 1.32 (0.71,2.44) |

Statistically significant results are given in bold. ORkl represents the odds ratio of Treatments k versus l.

3.2 Prevention of pain on injection with Propofol

Picard et al.29 conducted a quantitative systematic review to test the relative efficacy of analgesic interventions that had been used to prevent pain caused by Propofol injection. Veroniki et al.30 further evaluated inconsistency between the direct and indirect evidence in this data set. This data set contains 43 trials and 4495 subjects to compare eight treatments: (A) Placebo, (B) No treatment, (C) Lidocaine before, (D) Lidocaine mixed, (E) Lidocaine+tourniquet, (F) Opioids, (G) Metoclopramide, and (H) Temperature. Figure 2(b) shows the graphical representation of this network, where some direct comparisons are not available.

MOI iii has the smallest DICI among the five MOIs, while MOM i has a smaller DICM and is thus the better MOM. Thus, JM i is selected as the final model for this data set. Table 3 presents the posterior medians and corresponding 95% CIs for the estimated population-averaged event rates across the eight treatments. Comparing the results of JM i and MOI iii, we find 32.43% (i.e., (0.49–0.37)/0.37=32.43%) and 15.00% (i.e., (0.46–0.40)/0.40=15.00%) relative changes for the posterior medians of πB and πH, respectively, which are substantial and indicate nonignorable missingness. This seems to make sense because trials without a placebo- or no treatment-arm were not included in this NMA. In other words, trials comparing solely active treatments were excluded. However, an NMA that includes only placebo/no treatment comparisons may yield different results from one that does not consider placebo/no treatment comparisons, or one that considers both types of comparisons.15 Another phenomenon we observe in Table 3 is that JM i and JM ii yield quite different results for the estimated event rates, while the results of JM ii are closer to those of MOI iii, suggesting the necessity of heterogeneous missingness parameters α1k.

Table 3.

Posterior medians and their 95% credible intervals for the population-averaged event rates of the eight treatments in the data set about prevention of pain on injection with Propofol.

| MOI i | MOI ii | MOI iii | MOI iv | MOI v | JM i | JM ii | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| π A | 0.31 (0.25,0.37) | 0.31 (0.25,0.38) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.25,0.36) | 0.28 (0.21,0.35) | 0.30 (0.24,0.37) |

| πB | 0.35 (0.28,0.43) | 0.37 (0.30,0.46) | 0.37 (0.26,0.48) | 0.36 (0.28,0.47) | 0.36 (0.28,0.45) | 0.49 (0.29,0.65) | 0.38 (0.27,0.50) |

| πC | 0.55 (0.48,0.63) | 0.54 (0.44,0.63) | 0.58 (0.47,0.68) | 0.57 (0.45,0.69) | 0.57 (0.46,0.67) | 0.56 (0.40,0.71) | 0.59 (0.47,0.70) |

| πD | 0.63 (0.56,0.69) | 0.61 (0.53,0.69) | 0.63 (0.54,0.71) | 0.62 (0.52,0.71) | 0.63 (0.54,0.71) | 0.60 (0.46,0.72) | 0.63 (0.54,0.72) |

| πE | 0.82 (0.74,0.88) | 0.80 (0.70,0.87) | 0.80 (0.66,0.89) | 0.79 (0.64,0.89) | 0.82 (0.70,0.90) | 0.85 (0.71,0.93) | 0.80 (0.66,0.90) |

| πF | 0.62 (0.54,0.69) | 0.62 (0.54,0.70) | 0.61 (0.51,0.72) | 0.63 (0.53,0.71) | 0.63 (0.54,0.71) | 0.63 (0.46,0.78) | 0.62 (0.51,0.73) |

| πG | 0.62 (0.52,0.72) | 0.61 (0.45,0.71) | 0.68 (0.51,0.83) | 0.62 (0.33,0.82) | 0.65 (0.43,0.79) | 0.61 (0.34,0.86) | 0.70 (0.52,0.85) |

| πH | 0.44 (0.34,0.53) | 0.48 (0.35,0.61) | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.42 (0.25,0.62) | 0.47 (0.30,0.64) | 0.46 (0.26,0.65) | 0.41 (0.27,0.56) |

| DICM | —– | —– | —– | —– | —– | 333.3 | 366.7 |

| DICI | 648.0 | 619.6 | 569.1 | 571.3 | 571.3 | 574.0 | 573.5 |

πA–H represent the event rates for Treatments A–H. The bold cells highlight the smallest DICs.

Sensitivity to the prior distributions was also conducted and is summarized in Table 4. S1 and S2 investigate more informative versions of the normal prior distributions for μk, namely, N(0, 100) and N(0, 10), respectively. Heavy-tailed t-distributions with degrees of freedom 2 and 5 are also employed for μk (models S3 and S4). Table 4 shows that the estimated πA–H in S1–S4 are all close to those from MOI iii in Table 3 (Note that MOI i–iv use similar prior distributions; we pick MOI iii for illustration), thus MOI iii seems to be robust to these other prior distributions for the μk. S5 uses a more informative Uniform (0.01, 1) prior for standard deviation parameter σ, while S6 and S7 employ more informative Gamma priors for the precision τ = 1/σ2 with different shape and rate parameters (shape=1 and rate=0.5 in S6, and shape=3 and rate=1 in S7). It seems MOI iii is not particularly sensitive to the use of these prior distributions either. Next, sensitivity to the Wishart prior distribution for in MOI v is also explored. A W(V−1, 8) is employed in S8 and S9, where V is a 8×8 matrix with diagonal elements equal to 0.01 and 0.005, respectively, and offdiagonal elements equal to 0.005. Comparison of results from S8 and S9 with those from MOI v in Table 3 reveals that more informative Wishart priors do not appear to have a substantial effect on the estimates. In addition, following Barnard et al.,31 we also use a Wishart (I8, 9) prior for in sensitivity analysis (here K=8). Comparison of MOI v and S10 reveals that the estimated event rates for Treatments A, B, C, D, and F are robust, while those for Treatments E, G, and H are a little sensitive, perhaps due to smaller sample sizes (6, 4, and 7, respectively). Sample sizes for A, B, C, D, and F are 34, 11, 12, 18, and 12, which is also reflected by the node sizes in Figure 2(b). In addition, the total numbers of patients assigned to Treatments E, G, and H are 146, 245, and 264, compared with 1315, 341, 512, 1202, and 470 for A, B, C, D, and F.

Table 4.

Prior sensitivity analysis.

| MOI iii

|

MOI v

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 | S8 | S9 | S10 | |

| πA | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.24,0.36) | 0.30 (0.25,0.37) | 0.30 (0.24,0.37) |

| πB | 0.37 (0.26,0.48) | 0.37 (0.26,0.48) | 0.37 (0.27,0.48) | 0.37 (0.27,0.48) | 0.37 (0.26,0.48) | 0.37 (0.26,0.48) | 0.36 (0.26,0.48) | 0.36 (0.29,0.44) | 0.35 (0.28,0.42) | 0.35 (0.24,0.48) |

| πC | 0.58 (0.47,0.68) | 0.58 (0.47,0.68) | 0.57 (0.46,0.68) | 0.57 (0.47,0.68) | 0.58 (0.47,0.68) | 0.58 (0.47,0.68) | 0.58 (0.46,0.68) | 0.57 (0.47,0.67) | 0.56 (0.48,0.65) | 0.58 (0.45,0.69) |

| πD | 0.63 (0.53,0.71) | 0.63 (0.54,0.71) | 0.62 (0.53,0.7) | 0.62 (0.53,0.71) | 0.63 (0.54,0.71) | 0.63 (0.53,0.71) | 0.63 (0.53,0.71) | 0.63 (0.54,0.7) | 0.63 (0.55,0.7) | 0.62 (0.52,0.71) |

| πE | 0.80 (0.66,0.89) | 0.79 (0.66,0.89) | 0.78 (0.65,0.88) | 0.78 (0.65,0.88) | 0.79 (0.66,0.89) | 0.80 (0.66,0.89) | 0.80 (0.66,0.89) | 0.82 (0.72,0.9) | 0.83 (0.74,0.89) | 0.77 (0.59,0.88) |

| πF | 0.61 (0.5,0.72) | 0.61 (0.5,0.71) | 0.61 (0.5,0.71) | 0.61 (0.5,0.71) | 0.61 (0.5,0.72) | 0.61 (0.5,0.71) | 0.61 (0.5,0.71) | 0.63 (0.54,0.7) | 0.62 (0.54,0.69) | 0.63 (0.51,0.73) |

| πG | 0.68 (0.5,0.83) | 0.68 (0.5,0.83) | 0.66 (0.49,0.81) | 0.67 (0.5,0.82) | 0.68 (0.5,0.83) | 0.68 (0.5,0.83) | 0.68 (0.5,0.83) | 0.65 (0.42,0.77) | 0.66 (0.53,0.75) | 0.70 (0.45,0.87) |

| πH | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.40 (0.28,0.54) | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.40 (0.27,0.54) | 0.46 (0.32,0.62) | 0.46 (0.34,0.58) | 0.41 (0.24,0.6) |

S1: μk ~ N(0, 100); S2: μk ~ N(0, 10); S3: μk ~ t-dist (0, df = 2); S4: μk ~ t-dist (0, df = 5); S5: σ ~ Uniform (0.01,1); S6: τ ~ Gamma (1,0.5); S7: τ ~ Gamma (3, 1); , where V is a known 8 × 8 matrix with diagonal elements equal to 0.05 and off-diagonal elements equal to 0.005; , where V is a known 8 × 8 matrix with diagonal elements equal to 0.01 and off-diagonal elements equal to 0.005; . Posterior medians and their 95% credible intervals for the population-averaged event rates are reported. πA–H represent the event rates for Treatments A–H.

Table 5 shows the estimated ORs from JM i and JM ii. In JM i, Treatments C, D, E, F, and G are significantly better than Treatment A, and Treatment E is significantly better than Treatments B, C, D, F, and H. No other comparisons are statistically significant (i.e., all other CIs include 0). In JM ii, in addition to these significant results, Treatments C, D, F, and G are significantly better than Treatments B and H. This phenomenon seems consistent with the results in Table 3, where the estimated event rates from JM i and JM ii sometimes differ. In general, Treatment E (lidocaine+tourniquet) emerges as the most effective analgesic method, under either JM i or JM ii.

Table 5.

Posterior medians of ORs and their 95% credible intervals estimated from JM i and JM ii for the data set about prevention of pain on injection with Propofol.

| ORBA | ORCA | ORCB* | ORDA | ORDB* | ORDC | OREA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JM i | 2.53 (0.94,5.21) | 3.34 (1.73,6.70) | 1.36 (0.52,3.93) | 4.00 (2.26,6.92) | 1.61 (0.65,4.57) | 1.2 (0.48,2.81) | 15.47 (6.32,36.96) |

| JM ii | 1.41 (0.82,2.41) | 3.32 (2.06,5.49) | 2.36 (1.28,4.40) | 4.05 (2.69,6.08) | 2.88 (1.65,5.05) | 1.22 (0.70,2.10) | 9.68 (4.61,20.81) |

| OREB | OREC | ORED | ORFA | ORFB* | ORFC | ORFD | |

|

|

|||||||

| JM i | 6.28 (2.24,18.38) | 4.62 (1.63,12.80) | 3.86 (1.38,10.86) | 4.56 (2.10,9.79) | 1.87 (0.73,4.67) | 1.37 (0.48,3.71) | 1.13 (0.45,2.98) |

| JM ii | 6.88 (3.05,15.71) | 2.91 (1.30,6.53) | 2.39 (1.10,5.31) | 3.89 (2.36,6.43) | 2.76 (1.52,5.08) | 1.17 (0.64,2.12) | 0.96 (0.56,1.67) |

| ORFE | ORGA | ORGB* | ORGC | ORGD | ORGE | ORGF | |

|

|

|||||||

| JM i | 0.30 (0.10,0.83) | 4.18 (1.35,15.55) | 1.71 (0.40,9.18) | 1.25 (0.37,4.82) | 1.04 (0.29,4.55) | 0.27 (0.07,1.23) | 0.92 (0.22,4.47) |

| JM ii | 0.40 (0.18,0.89) | 5.40 (2.53,13.26) | 3.85 (1.60,10.19) | 1.63 (0.72,4.05) | 1.34 (0.59,3.40) | 0.56 (0.21,1.66) | 1.39 (0.60,3.57) |

| ORHA | ORHB | ORHC* | ORHD* | ORHE | ORHF* | ORHG* | |

|

|

|||||||

| JM i | 2.23 (0.88,5.12) | 0.91 (0.35,2.18) | 0.66 (0.21,1.94) | 0.56 (0.20,1.47) | 0.14 (0.04,0.44) | 0.49 (0.16,1.37) | 0.53 (0.10,2.25) |

| JM ii | 1.61 (0.86,2.97) | 1.15 (0.58,2.22) | 0.49 (0.23,0.97) | 0.40 (0.21,0.75) | 0.17 (0.07,0.39) | 0.41 (0.20,0.83) | 0.30 (0.11,0.74) |

Statistically significant results are given in bold. ORkl represents the odds ratio of Treatments k versus l.

shows ORs statistically significant in JM ii but not in JM i.

4 Simulations

We conducted two simulation studies to evaluate the performance of our proposed method. In Simulation 1, data are generated under nonignorable missing mechanism. Models ignoring and incorporating this mechanism are compared. In Simulation 2, we explore whether our proposed method still performs well when the missingness is ignorable, and check the performance of the CB method8 under this ignorable missingness as well.

4.1 Simulation setups

We generate a binary-data NMA of 30 trials comparing three treatments (1, 2, and 3) for both simulations. For convenience, we assume 100 patients are assigned to each treatment arm; 1000 replicates of simulated data sets are generated. The relative bias, defined as the difference between the true value and the mean of 1000 posterior estimates divided by the true value, and the empirical mean squared error (MSE) are calculated as measures of performance.

4.1.1 Simulation 1

We first assess the performance of our proposed method under nonignorable missingness, i.e., the MNAR mechanism. Data are generated according to MOI iii, which emerged as the best MOI for both real data sets. We set the true parameters of interest as follows: treatment-specific fixed effects μ1 = −1.4, μ2 = −1.0, and μ3 = −0.8, standard deviation σ = 0.4, and correlation coefficient ρ = 0.5. The probability of response for Treatment k in Trial i, pik, is generated according to Φ−1(pik) = μk + νik, where (νi1, νi2, …, νiK) has an exchangeable correlation matrix with the same correlation parameter ρ and variance parameter σ2. Then, the artificial data yik are generated by yik ~ Bin(100, pik). The corresponding true odds ratios comparing three treatments are OR21 = 2.00, OR31 = 2.77, and OR32 = 1.38.

We assume Treatments 1 and 3 are fully observed, whereas Treatment 2 is missing not at random. Therefore an NMA, with some trials comparing all three treatments of interest and the others comparing just two of them, is generated. We let the probability of missingness for Treatment 2 depend on the missing values themselves yi2 through formula , which brings nonignorable missingness.

Our investigation is based on fitting five models (MMAR, MMNAR1, MMNAR2, MMNAR3, and MMNAR4), as specified in Table 6. MMAR is set to be exactly the same as MOI iii, which ignores the nonignorable missingness. MMNAR1 uses MOI iii as the MOI and as the MOM. Since the missingness parameter is set to be 0, it is actually equivalent to the MMAR model. For MMNAR2, both parts of the model are correctly specified, i.e., MOI iii as the MOI, and as the MOM (note that the estimated pi2 is an approximation for ). MMNAR3 and MMNAR4 have overly complex forms for missingness, i.e., and , respectively, jointly modeled with MOI iii. In general, MMNAR2, MMNAR3, and MMNAR4 consider nonignorable missingness, while MMAR and MMNAR1 disregard nonignorable missingness.

Table 6.

Specifications of fitted models in Simulation 1.

| Model name | Model of interest | Model of missingness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMAR | MOI iii | NA | |

| MMNAR1 | MOI iii |

|

|

| MMNAR2 | MOI iii |

|

|

| MMNAR3 | MOI iii |

|

|

| MMNAR4 | MOI iii |

|

MOI iii: Φ−1(pik) = μk + νik, where (νi1, νi2, …, νiK) has an exchangeable correlation matrix with the same correlation parameter ρ and variance parameter σ2. α0 is a scalar parameter, and α1 is the missingness parameter.

4.1.2 Simulation 2

In this section, we choose MOI iii as the true model, and use the same parameters of interest as in Simulation 1 to generate the simulated data sets. The true odds ratio is thus the same as well. Similar incomplete block structure for the data set is generated (i.e., Treatment arms 1 and 3 are fully observed whereas Treatment arm 2 contains missing data) except that the probability of missingness for Treatment 2 is dependent on the observed data yi1, i.e., , rather than on the missing values themselves yi2.

We now fit four models (MMAR, MMNAR2, MHOM and MID) and compare their performances. MMAR and MMNAR2 have the same specifications as Simulation 1 in Table 6. MHOM and MID are the HOM and ID models proposed in Lu and Ades,8 namely

| (4) |

where μi is the specified baseline effect that is commonly regarded as a nuisance parameter; Xik is the indicator for baseline, taking value 0 when k=b and 1 when k ≠ b; b(i) is the specified baseline treatment in the i-th trial, commonly denoted by b for simplicity as above; and δibk represents the contrast between Treatments k and b for the i-th trial and is assumed to have a normal distribution with mean dbk and variance . This method assumes that dhk=dbk − dbh. With heterogeneous variances , we call this model MID; if the variances are set to be homogeneous at σ2, we call it MHOM.

4.2 Simulation results

We now summarize the results from the two simulation studies separately.

4.2.1 Simulation 1

Table 7 provides evidence that ignoring nonignorable missingness will lead to biases. MMAR and MMNAR1 produce larger relative biases and MSEs for OR21 and OR32 than the true MMNAR2 and overly complex MMNAR3 and MMNAR4. For example, the relative bias for OR21 is −0.11 from MMAR and MMNAR1, while it is only −0.04 from MMNAR2 and MMNAR3, and −0.08 from MMNAR4; the relative bias for OR32 is 0.16 from MMAR and MMNAR1, while it is 0.08 from MMNAR2 and MMNAR3, and 0.11 from MMNAR4. Note that MMAR and MMNAR1 produce exactly the same results because these two models are actually the same (MMNAR1 uses as the MOM); while MMNAR2 and MMNAR3 also generate very similar results (the differences are only in the third decimal place thus not shown in Table 7) because the overly complex term is not influential to the results.

Table 7.

Performances of various models when MNAR is present.

| OR21 | OR31 | OR32 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReBias | MMAR | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| MMNAR1 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.16 | |

| MMNAR2 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| MMNAR3 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| MMNAR4 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.11 | |

| MSE | MMAR | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| MMNAR1 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.11 | |

| MMNAR2 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.07 | |

| MMNAR3 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.07 | |

| MMNAR4 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.10 |

The MSEs show similar results. For OR21, the MSEs are 0.14 from MMAR and MMNAR1, 0.13 from MMNAR2, MMNAR3 and MMNAR4; for OR32, the MSEs are 0.11 from MMAR and MMNAR1, 0.07 from MMNAR2 and MMNAR3, and 0.10 from MMNAR4. Thus, we conclude that joint models MMNAR2, MMNAR3, and MMNAR4 incorporating nonignorable missingness do outperform MMNAR1 and MMAR, though misspecification of the missingness may slightly affect the model performance as is shown by MMNAR4.

Note that the relative biases and MSEs for OR31 from all models are the same because Treatments 1 and 3 are fully observed. All models perform similarly well with very small relative bias, i.e., 0.01.

4.2.2 Simulation 2

Table 8 compares the performances of MMAR, MMNAR2, and the CB MHOM and MID models, when the missing data are generated under MAR mechanism. MMAR is almost unbiased for all OR estimates; MMNAR2 produces estimates with very small biases; while the CB MHOM and MID models show much bigger biases. Let us take OR21 as an example, the relative biases are 0.01 from MMAR, 0.08 from MMNAR2, 0.14 from MHOM, and 0.15 from MID.

Table 8.

Performances of the proposed method and the CB method under MAR mechanism.

| OR21 | OR31 | OR32 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReBias | MMAR | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| MMNAR2 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.06 | |

| MHOM | 0.14 | 0.10 | −0.02 | |

| MID | 0.15 | 0.11 | −0.01 | |

| MSE | MMAR | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| MMNAR2 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.04 | |

| MHOM | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.06 | |

| MID | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.06 |

The conclusions regarding these four models from the MSEs are similar. With OR21 as an example again, the MSEs are 0.10 from MMAR, 0.14 from MMNAR2, 0.23 from MHOM, and 0.27 from MID. In summary, our proposed method works well, even if missingness is ignorable. In contrast, the CB methods produce larger biases and MSEs under the MAR mechanism.

In a nutshell, our proposed method still performs well even if the missingness is at random and permits sensible results under the MNAR mechanism. When the results of models assuming MAR show big differences from models assuming MNAR, attention is needed to potential nonignorable missingness; failure to do so may lead to biased estimations.

5 Discussion

Although clinical and policy-making interest often lies in comparing active treatments, new drugs are often compared with placebo or standard treatments in order to obtain approval for drug licensing.32 In addition, it is unrealistic to expect that comparisons of all treatments of interest will be provided from any single trial, as most trials are only two or three arms. NMA, if properly applied, can serve decision making as a better tool than pairwise meta-analysis33 by providing indirect comparison results, simultaneous inference regarding multiple treatments, and more precise estimation. Thus, it has the potential to bring tremendous changes to the practice of evidence-based medicine.

Deliberate choices of treatments by clinicians or selective choices of treatments by meta-analysts may lead to MNAR. Neither the CB methods5–8 nor the AB method9 can easily handle this challenging situation. In this paper, we extended the AB method in Zhang et al.9 to incorporate nonignorable missingness using selection models and applied the proposed method to two real data sets. The smoking cessation data set did not show evidence of nonignorable missingness, but serious nonignorable missingness appeared in the analysis of the prevention of pain on injection with Propofol data set. Simulation studies showed that our proposed method incorporating nonignorable missingness produced less-biased estimates when nonignorable missingness was present and did not hurt if the missingness was ignorable.

A major criticism of the AB method is the assumption that the actual event rates are exchangeable across studies (i.e., exchangeability of absolute study effects), potentially allowing the control rate in one study to influence estimation of the treatment effect in another. In a meta-analysis, studies are firstly screened and collected according to some inclusion criteria, which contains characteristics of the target populations. A (usually CB) meta-analysis is then carried out under the fundamental assumption that treatment contrasts are exchangeable across studies. However, this assumption can be violated if selected studies do not represent a common target population.12,34 In the same vein, our assumption of exchangeable event rates seems to be plausible if the studies of an NMA come from a common superpopulation. AB thinking has already been applied in traditional meta-analysis.35,36 Senn37 discussed this controversial issue, and concluded that the amount of bias arising from the AB method is likely to be low, and thus little harm is likely to be done in practice. Senn also acknowledged some advantages of the AB method in traditional meta-analysis.

One advantage of the AB method over the CB methods is that the AB method can sensibly include one-arm studies alongside comparative studies. AB methods assume missing arms to be MAR and imputes them through MCMC, and thus one-arm trials can still contribute to the likelihood function. CB methods require a baseline treatment for each study (i.e., at least two arms) and are thus unable to synthesize one-arm studies. Inclusion of one-arm studies in synthesis has been widely discussed in the literature,38,39 and the AB method can be a nice alternative, though requires careful consideration of heterogeneity between the different designs, as well as potential bias introduced when adding one-arm studies. In addition, this is intimately related to the flexibility of the AB method. Suppose we have an NMA aiming to compare Treatments A, B, and C but only sparse information on A is available. The AB method can utilize information of A from trials of A versus D, while the CB methods cannot.

The selection model is intuitively appealing because it shows how the probabilities of missingness depend directly on the data values and also that the factorization directly specifies f (Yobs, Ymis|θ), which is the distribution in which analysts are usually interested. However, the selection model relies heavily on the correct specification of the model form.10 Thus, the performance of this method is model-, data-, and context-specific, as expected. Alternatively, pattern-mixture models do not require correct specification of the precise model form, albeit with their own limitations; for example, they are by construction underidentified and require identifying constraints.40 Methods that utilize advantages of both selection and pattern-mixture models await further development.

Future work also looks toward approaches for handling inconsistency and publication bias. Inconsistency, defined as apparent discrepancy between direct and indirect comparisons of two treatments, is one of the major issues in NMA. The extensive criticism of NMA is associated with the difficulty in evaluating the assumption underlying the statistical synthesis of direct and indirect evidence. Current existing methods assessing inconsistency have their own drawbacks or are cumbersome to apply; see Hong et al.41 for a recent Bayesian alternative. Publication bias, the concern that studies with significant results are more likely to be published and published studies are more likely to be included in a meta-analysis, is another potentially serious issue42 in NMA. User-friendly approaches that test as well as account for inconsistency and publication bias need further effort.

Overall, many health care practitioners remain somewhat skeptical of NMA and tend to give priority to direct evidence to inform decision making because this emerging statistical technique is still somewhat imperfect. Besides the issues of inconsistency and publication bias, the assumption underlying the models, the statistical expertise required to fit them, and the lack of an interpretable and simple measure to evaluate the risk of biases all contribute to this skepticism. Future research should focus on these issues and their evaluation, interpretation, and applicability.

Acknowledgments

Funding

JZ was supported in part by the NIAID AI103012. HC was supported in part by the NIAID AI103012, NIDCR R03DE024750, NCI P30CA077598, and NIMHD U54-MD008620. BPC was supported in part by the NIAID AI103012 and the US NCI 1R01-CA157458-01A1.

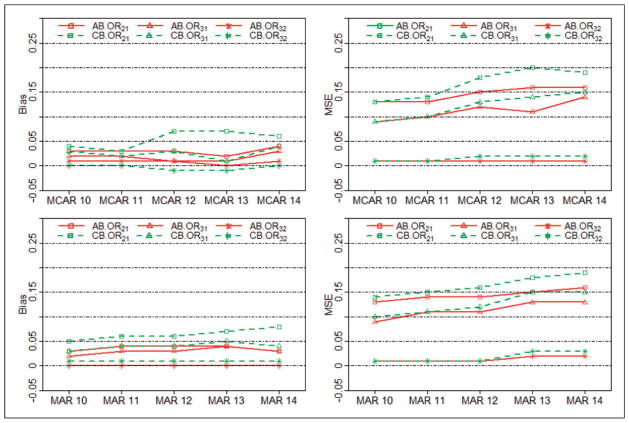

Appendix 1. A Simulation studies comparing AB and CB methods

In this appendix, we aim to compare the performances of the AB method proposed in Zhang et al. (2014) [9] and the CB method proposed in Lu & Ades (2009) [8], under missing completely at random (MCAR) and MAR mechanisms.

Simulation setup

A network meta-analysis containing 30 trials comparing three treatments is generated according to the unstructured heterogeneous-variance model MOI v specified in the main paper, i.e., pik = Φ(μk + νik), where (νi1, …, νiK)T ~ MVN(0,Σk) and Σk is the covariance matrix determined by correlation parameters ρ = (ρ12, ρ13, ρ23) and standard deviation parameters σ = (σ1, σ2, σ3). We let the mean parameters have values μ1 = −1.0, μ2 = −0.5, and μ3 = −0.8, standard deviation parameters have values σ1 = 0.3, σ2 = 0.4, and σ3 = 0.5, and correlation coefficients have values ρ12 = 0.4, ρ13 = 0.5, and ρ23=0.6. The response rate pik for the k-th treatment in the i-th trial is calculated according to the above MOI v formula and specified parameters. Then the number of binary responses {yik} are randomly generated from a binomial distribution with n=100 and probabilities pik. Note that the above parameters correspond to the true population-averaged treatment-specific response rates π1 = 0.17, π2 = 0.32, and π3 = 0.24, and thus the true odds ratios are OR21 = 2.33, OR31 = 1.53, and OR32=0.66.

Let rik be the missingness indicator, taking value 1 when the record for the k-th treatment in the i-th trial is missing and 0 when the record is present, and be the corresponding probability of missingness. We consider simulated scenarios of missingness mimicking the characteristics of the real smoking cessation data, where most of the trials (22) are two-arm and only a few (2) are three-arm. Treatment 2 is assumed to be completely observed, while Treatments 1 and 3 have missing values. We let nmis=10, 11, 12, 13, 14 trials be missing for Treatment 3, and then another nmis trials be missing for Treatment 1 selected from the remaining 30 – nmis, ensuring each trial contains at least two treatments (while 30 – 2nmis have 3). For the MCAR situation, the missingness of Treatments 3 and 1 are determined by and respectively. For the MAR situation, the missingness of Treatment 3 is determined by , whereas the missingness of Treatment 1 is determined by . Note that in missing data simulations it is a common approach to generate complete data first and then randomly delete some, leaving the missing percentage unknown. We instead first decide how many trials will be deleted and then select these trials according to and , until the pre-determined number of missing trials is obtained. In this way, we are able to track the model performance under various missingness percentages.

We now fit two models to the simulated data sets. One is the unstructured heterogeneity AB model proposed by Zhang et al. [9], and the other is the unstructured heterogeneity CB model proposed by Lu and Ades [8]. These two models are labeled as MOI v and ID model, respectively, in Figure 1 in the main paper.

Simulation results

Figure 4 presents the biases and MSEs of ORs (OR21, OR31, and OR32) obtained from the AB method and the CB method under both MCAR and MAR mechanisms. Bias from the AB method is consistently smaller than 0.05 for all nmis = 10, 11, 12, 13, or 14 under both mechanisms, whereas bias from the CB method sometimes is bigger than 0.05 (see the two plots in the left column of Figure 4). Under both MCAR and MAR mechanisms, MSE from the AB method (the right column of Figure 4) is consistently smaller than from that of CB method for different nmis values. This suggests that the AB method is less biased than the CB method. Another phenomenon observed in Figure 4 is that the difference between two methods is smaller when the number of missing trials is small, e.g. when nmis = 10 and 11. However, when nmis becomes bigger, e.g. 12, 13, and 14, closer to the missing situation in the real smoking cessation data, the AB method is more robust. In general, the AB method outperforms the existing CB method in terms of bias and MSE under both MCAR and MAR mechanisms.

Figure 4.

Performance comparisons for the AB9 and CB8 methods. Biases and MSEs under both MCAR and MAR mechanisms are shown.

Appendix 2. Real data analysis results with different link functions for MOMs

Table 9 compares the results using the logit link for the MOMs with those obtained using a probit link for the MOMs for the smoking cessation data. Results from both JM i and JM ii are presented. We can see that the different link functions produce similar results for both joint models. Table 10 presents corresponding results for the prevention of pain on injection with Propofol data set; again, changes are very modest. In summary, both the logit and probit link functions seem to work equally well.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Li T, Puhan MA, Vedula SS, et al. Network meta-analysis – highly attractive but more methodological research is needed. BMC Med. 2011;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins JPT, Whitehead A. Borrowing strength from external trials in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1996;15:2733–2749. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19961230)15:24<2733::AID-SIM562>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, et al. Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis for health-care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health. 2011;14:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:746–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2004;23:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu G, Ades AE. Assessing evidence inconsistency in mixed treatment comparisons. JASA. 2006;101:447–459. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu G, Ades AE, Sutton AJ, et al. Meta-analysis of mixed treatment comparisons at multiple follow-up times. Stat Med. 2007;26:3681–3699. doi: 10.1002/sim.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu G, Ades AE. Modeling between-trial variance structure in mixed treatment comparisons. Biostatistics. 2009;10:792–805. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Carlin BP, Neaton JD, et al. Network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials: reporting the proper summaries. Clin Trials. 2014;11:246–262. doi: 10.1177/1740774513498322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pigott TD. A review of methods for missing data. Educ Res Eval. 2001;7:353–383. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong H, Chu H, Zhang J, et al. Methods Research Reports. Rockville, USA: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; A Bayesian missing data framework for generalized multiple outcome mixed treatment comparisons. Report no. 13-EHC004-EF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shuster JJ, Guo JD, Skyler JS. Meta-analysis of safety for low event-rate binomial trials. Res Synth Meth. 2012;3:30–50. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalmers TC, Celano P, Sacks HS, et al. Bias in treatment assignment in controlled clinical trials. New Engl J Med. 1983;309:1358–1361. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312013092204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills EJ, Kanters S, Thorlund K, et al. The effects of excluding treatments from network meta-analyses: survey. BMJ. 2013;347:f5195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman CI, Phung OJ, Cappelleri JC, et al. Use of mixed treatment comparisons in systematic reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. prepared by the University of Connecticut/Hartford Hospital Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No 290-2007-10067-I AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC119-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heckman JJ. The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Ann Econ Soc Measure. 1976;5:475–492. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason A, Richardson S, Best N. Two-pronged strategy for using DIC to compare selection models with non-ignorable missing responses. Bayesian Anal. 2012;7:109–146. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelman A. Prior distributions for variance parameters in hierarchical models. Bayesian Anal. 2006;1:515–533. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafson P. The utility of prior information and stratification for parameter estimation with two screening tests but no gold standard. Stat Med. 2005;24:1203–1217. doi: 10.1002/sim.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafson P, Hossain S, MacNab YC. Conservative prior distributions for variance parameters in hierarchical models. Can J Stat. 2006;34:377–390. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natarajan R, McCulloch CE. Gibbs sampling with diffuse proper priors: a valid approach to data-driven inference? J Comput Graph Stat. 1998;7:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakefield J. Ecological inference for 2×2 tables (with discussion) J R Stat Soc Ser A (Stat Soc) 2004;167:385–445. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson C, Best N, Richardson S. Improving ecological inference using individual-level data. Stat Med. 2006;25:2136–2159. doi: 10.1002/sim.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, et al. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit (with discussion) J R Stat Soc Ser B (Stat Methodol) 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Celeux G, Forbes F, Robert CP, et al. Deviance information criteria for missing data models. Bayesian Anal. 2006;1:651–673. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Smoking cessation. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 18 (AHCPR publication no. 96-0692) Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasselblad V. Meta-analysis of multitreatment studies. Med Decis Making. 1998;18:37–43. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9801800110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Picard P, Tramer MR. Prevention of pain on injection with propofol: a quantitative systematic review. Anesth Anal. 2000;90:963–969. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200004000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veroniki AA, Vasiliadis HS, Higgins JP, et al. Evaluation of inconsistency in networks of interventions. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:332–345. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnard J, McCulloch R, Meng XL. Modeling covariance matrices in terms of standard deviations and correlations, with application to shrinkage. Stat Sin. 2000;10:1281–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton AJ, Higgins JPT. Recent developments in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2008;27:625–650. doi: 10.1002/sim.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Meth. 2012;3:80–97. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Fu H, Carlin BP. Detecting outlying trials in network meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2015:34. doi: 10.1002/sim.6509. Epub ahead of print 8 April 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Houwelingen HC, Zwinderman KH, Stijnen T. A bivariate approach to meta-analysis. Stat Med. 1993;12:2273–2284. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780122405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shuster JJ, Jones LS, Salmon DA. Fixed vs random effects meta-analysis in rare event studies: The rosiglitazone link with myocardial infarction and cardiac death. Stat Med. 2007;26:4375–4385. doi: 10.1002/sim.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senn S. Hans van Houwelingen and the art of summing up. Biometr J. 2010;52:85–94. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200900074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Begg CB, Pilote L. A model for incorporating historical controls into a meta-analysis. Biometrics. 1991;47:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viele K, Berry S, Neuenschwander B, et al. Use of historical control data for assessing treatment effects in clinical trials. Pharm Stat. 2014;13:41–54. doi: 10.1002/pst.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michiels B, Molenberghs G, Bijnens L, et al. Selection models and pattern-mixture models to analyse longitudinal quality of life data subject to drop-out. Stat Med. 2002;21:1023–1041. doi: 10.1002/sim.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao H, Hodges JS, Ma H, et al. Hierarchical Bayesian approaches for detecting inconsistency in network metaanalysis. Division of Biostatistics, University of Minnesota; 2015. Research Report 2014–006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]