Introduction

Patient Blood Management (PBM) is a holistic approach to the management of blood as a resource for each, single patient; it is a multimodal strategy that is implemented through the use of a set of techniques that can be applied in individual cases. Indeed, the overall outcome resulting from the implementation of PBM cannot be fully appreciated and explained simply by summing the effects of the single strategies and techniques used, since these can only produce the expected optimal outcome if used in combination1. PBM is, therefore, a patient-centred, multiprofessional, multidisciplinary and multimodal approach to the optimal management of anaemia and haemostasis (also during surgery), to limiting allogeneic transfusion needs in the peri-operative period, and to appropriate use of blood components and, when relevant, plasma-derived medicinal products2. The concept of PBM is not centred on a specific pathology or procedure, nor on a specific discipline or sector of medicine, but is aimed at managing a resource, “the patient’s blood”, shifting attention from the blood component to the patient who, therefore, acquires a central and pre-eminent role3,4.

PBM combines the dual purposes of improving the outcomes of patients and reducing costs, being based on the patient rather than on allogeneic blood as the resource. For this reason, PBM goes beyond the concept of appropriate use of blood components and plasma-derived medicinal products, since its purpose is to avoid or significantly reduce their use, managing, in good time, all the modifiable risk factors that can lead to a transfusion being required5. These aims can be achieved through the so-called “three pillars of PBM” (Table I)5, which are crucial for making the paradigmatic shift that characterises the innovative, patient-centred approach: (i) optimising the patient’s erythropoiesis; (ii) minimising bleeding; and (iii) optimising and exploiting an individual’s physiological reserve to tolerate anaemia5. Each of these three key points is a strategic response to clinical circumstances that can cause adverse outcomes and necessitate the use of allogeneic transfusion therapy, namely anaemia, blood loss and hypoxia, respectively.

Table I.

The three pillars of Patient Blood Management (modified from Hofmann A et al.5).

| Period | Pillar 1 | Pillar 2 | Pillar 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimisation of erythropoiesis | Minimisation of blood loss | Optimisation of tolerance of anaemia | |

| Pre-operative |

|

|

|

| Intra-operative |

|

|

|

| Post-operative |

|

|

|

PBM is, therefore, intended to guarantee all patients a series of personalised programmes, based on surgical requirements and the characteristics of the patients themselves, with the dual purposes of using allogeneic transfusion support appropriately and reducing the need for this resource. For this reason, PBM requires multidisciplinary and multimodal strategies to systematically identify, evaluate and manage anaemia (boosting, if necessary, individual physiological reserves) and to avoid or minimise blood losses.

It seems necessary to produce specific national standards. In fact, in the USA, PBM is the object of attention from the Association for Advancing Transfusions and Cellular Therapies (formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks - AABB) which recently published the first edition of “Standards for a Patient Blood Management Program” precisely with the aim of supplying healthcare structures with solid elements for the standardisation of procedures and activities for implementing and/or optimising a PBM programme. The Society for the Advancement of Blood Management (SABM), also in the USA, has published a second edition of “Administrative and Clinical Standards for Patient Blood Management Programs”6 and the Joint Commission has published seven parameters for measuring the performance of healthcare structures in the field of PBM7.

Methodology for producing the recommendations for the implementation of a Patient Blood Management programme

The methodology used to prepare the recommendation grades is based on that described by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group8. According to the GRADE system, recommendations are classified by grade, expressed in Arabic numbers (1, 2), according to their strength, and in letters (A, B, C), according to the quality and type of evidence derived from the studies.

In detail:

- Grade 1: the authors are certain that the advantages for health clearly outweigh the disadvantages, in terms of both risk and financial cost. This is, therefore, a strong recommendation.

- Grade 2: the authors are less certain, the balance between advantages and disadvantages is less clear.

This is, therefore, a weak recommendation.

As far as concerns the quality and type of evidence drawn from the studies on which the recommendations are based, these can be classified into three levels:

- Grade A: high level. The evidence is derived from numerous, consistent randomised trials without major limitations. It is unlikely that future research will change the conclusions of these trials.

- Grade B: moderate level. The evidence is derived from randomised clinical trials, but with major limitations (such as inconsistent results, wide confidence intervals, methodological weaknesses). Grade B is also attributed to recommendations deriving from strong evidence from observational studies or case series (for example, treatment effects or the demonstration of a dose-response effect). Subsequent research could modify the conclusions of these trials.

- Grade C: low or very low level. The evidence is derived from the analysis of observational clinical studies with less consistent results, or from experts’ opinions/clinical experience. Future research is likely to change the conclusions reached.

In brief:

- Grade 1A: strong recommendation based on scientific evidence of high quality.

- Grade 1B: strong recommendation based on scientific evidence of moderate quality.

- Grade 1C: strong recommendation based on scientific evidence of low quality.

- Grade 2A: weak recommendation based on scientific evidence of high quality.

- Grade 2B: weak recommendation based on scientific evidence of moderate quality.

- Grade 2C: weak recommendation based on scientific evidence of low quality.

The clinical-organisational course of the patient undergoing elective major orthopaedic surgery

Pre-operative period and role of the pre-operative assessment

The pre-operative assessment is performed in order to obtain clinical and laboratory information supplementary to that acquired from the clinical history with the aim of9:

- confirming, or not, the planned diagnostic-therapeutic pathway (clinical management);

- identifying previously undetected disorders that must be treated before the operation or which make it necessary to modify the surgical or anaesthetic technique;

- limiting possible adverse outcomes or increasing the benefits for patient by modifying, if necessary, the clinical pathway;

- facilitating the evaluation of potential risks for the patient (including the possibility of informing the patient of a potentially increased risk);

- predicting possible post-operative complications;

- establishing the baseline reference parameters, which can be used for subsequent post-operative evaluations;

- considering the value of performing screening not related to the operation.

A pre-operative evaluation is always necessary when anaesthesia is planned.

Selective use of pre-operative tests, based on the history, clinical examination, and type and invasiveness of the surgical and anaesthesiological procedures, helps the management of the patient.

In order to shorten the time spent in hospital and optimise the planning of elective surgery, the pre-operative evaluation is performed in an out-patient setting (pre-admission), at an appropriate time before the operation (on average, 30 days before), and includes any additional clinical-diagnostic investigations needed10–12.

In all candidates for elective surgery, a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach must be used, based on an agreed programme of co-ordinated interventions, aimed at peri-operative management of the “patient’s blood” as a resource. These interventions start with the pre-operative optimisation of erythropoiesis, haemostasis and tolerance of anaemia.

Depending on the organisation in different hospitals or healthcare authorities, pre-operative management of the resource “patient’s blood” must guarantee a structured diagnostic-therapeutic pathway involving at least three specialists: a surgeon, an anaesthetist and a transfusion medicine specialist; these professionals collaborate in the setting of a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic (the Anaemia Clinic) which takes the role of case manager. The Anaemia Clinic must allow for, when necessary, the inclusion and collaboration of other medical staff, such as experts in haemostasis and thrombosis, haematologists, cardiologists or other specialists with expertise in identifying and treating, in a multidisciplinary and multimodal method, underlying disorders in candidates for elective surgery. Furthermore, the patient’s general practitioner should be kept informed and, when possible, involved.

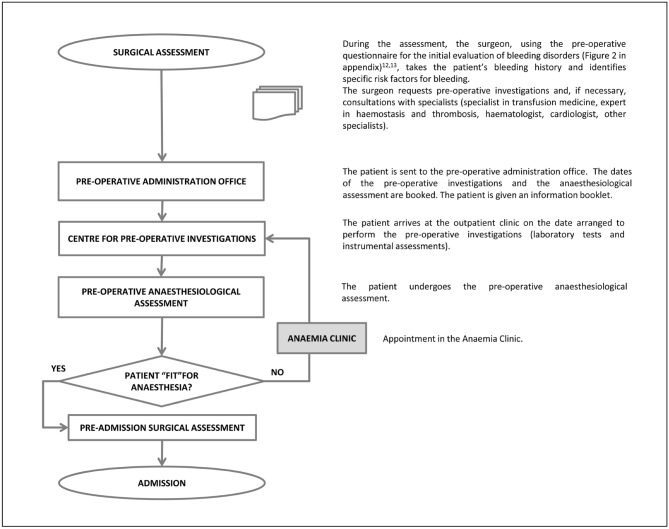

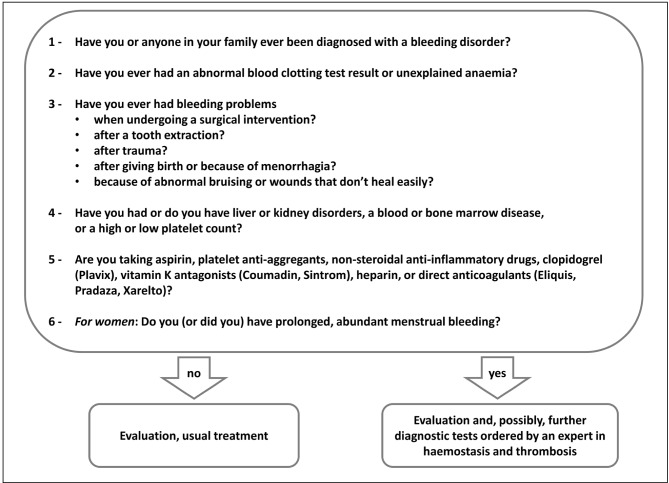

The pre-operative process starts in the surgical outpatient clinic (Figure 1). During this appointment the surgeon, having defined the indication for surgery, the grading of the intervention and its level of priority, takes the patient’s history, with the purpose, among others, of detecting risk factors for bleeding. To this aim it can be useful to administer a questionnaire for an initial evaluation of bleeding disorders (Figure 212,13), which can be followed by appropriate pre-operative investigations.

Figure 1.

Pre-operative flow-chart for patients undergoing elective major orthopaedic surgery and included in a Patient Blood Management programme.

Figure 2.

Initial evaluation of bleeding disorders (modified from Liumbruno GM et al.12, Nichols WL et al.13).

Subsequently the patient is sent to the pre-operative administration office which, in conformity with locally used procedures, enters the patient into a specific pre-operative course aimed at booking and performing the pre-operative investigations and anaesthesiological evaluation, as well as adding the patient to the waiting list (surgical register).

Once the prescribed investigations have been performed in a centre for pre-operative examinations, the patient is sent to the pre-operative anaesthesiology clinic where the anaesthetist examines the results of the pre-operative investigations and evaluates the patient’s clinical state; if the patient is considered fit for anaesthesia, the specialist defines the “risk class”14, obtains informed consent to the anaesthesia and prescribes the anaesthesiological pre-medication.

If the pre-operative investigations that have been carried out are not considered sufficient, the anaesthetist orders other investigations that will be performed, when possible, on the same day as ordered or, at any rate, as soon as possible (dedicated pre-operative pathway). Furthermore, the anaesthetist may consider that the patient is not fit for anaesthesia because of the presence of intercurrent or chronic disorders or anaemia, which require specific investigations and/or treatment. In this case, after consultation with the surgeon and/or other specialists of the Anaemia Clinic, the anaesthetist may decide to prescribe what is deemed useful, setting a new date for the anaesthesiological re-evaluation, through the centre for pre-operative investigations.

The specialists of the Anaemia Clinic (anaesthetist, surgeon, specialist in transfusion medicine, expert in haemostasis and thrombosis, haematologist, or other specialist with expertise in identifying and treating, in a multidisciplinary and multimodal method, underlying disorders in candidates for elective surgery), by adopting the strategies and techniques indicated in the three pillars of PBM (Table I)5, have the task of setting up the multidisciplinary programme of co-ordinated interventions, aimed at the peri-operative management of the resource “patient’s blood”. The three pillars of the PBM in the pre-operative period are:

Optimisation of erythropoiesis: detect anaemia; identify and treat its underlying causes; re-evaluate the patient, if necessary; treat iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anaemia, anaemia of chronic disease and functional iron deficiencies, so-called iron-restricted erythropoiesis; treat deficiencies of other haematinics.

Minimise blood losses: identify and manage bleeding risk, minimise iatrogenic bleeding, plan the procedure carefully and prepare well; organise pre-operative autologous blood donation in very selected cases.

Optimisation of the tolerance of anaemia: assess and optimise the patient’s physiological reserve to tolerate anaemia and risk factors; compare estimated blood loss with the individual patient’s tolerable blood loss; formulate a personalised blood management programme that includes patient-specific blood-conservation techniques; adopt restrictive blood transfusion thresholds.

Information about strategies included in local PBM programmes should be supplied to all patients, preferably before their admission to hospital, because this improves compliance with diagnostic-therapeutic care pathways adopted in the healthcare structure.

- It is recommended that the patient’s pre-operative evaluation, aimed at detecting any anaemia and optimising erythropoiesis, at identifying and managing bleeding risk as well as assessing and optimising the patient’s personal physiological tolerance of anaemia and risk factors, be carried out at least 30 days before the planned date of the operation, in order to allow more detailed investigations and/or arrange appropriate treatment [1C].

- It is recommended that a structured questionnaire, aimed at picking up risk factors for bleeding, is included when taking the clinical history of an adult candidate for elective (orthopaedic) surgery [1C].

- It is recommended that all adult patients who are candidates for elective major orthopaedic surgery for which a multidisciplinary programme of co-ordinated interventions has been established involving the adoption of pharmacological and non-pharmacological techniques aimed at optimising erythropoiesis, minimising blood losses and optimising tolerance of anaemia, before giving consent to one or more of the above-mentioned treatments, receive detailed information on their clinical state and strategies to limit allogeneic transfusion needs included in the local PBM programme; explanatory material prepared ad hoc by the hospital may be used for this purpose [1C].

Once the pre-operative process has been concluded with the patient deemed fit for anaesthesia, the patient undergoes the pre-admission surgical assessment, with the purposes of: a) re-evaluating the grading of the operation to be performed; b) re-assessing the patient’s general and specific conditions; c) planning the procedure; d) filling in the clinical records and single treatment chart with the pre-operative prescriptions (for example: specific therapies to optimise erythropoiesis, antibiotic prophylaxis, anti-thrombotic prophylaxis); e) collecting the informed consent to the intervention.

Having reached this point of the diagnostic-therapeutic care pathway, the patient is ready to be admitted to hospital on the planned day.

Intra-operative period

Once the patient has completed the pre-operative preparation for anaesthesia and the operation, on the planned day the patient is admitted to the surgical ward, where he or she is greeted by a nurse. The nursing staff fill in the nursing records with the planned assessment forms (for example: pain detection, detection of pressure ulcers) and check that the patient has been suitably prepared with respect to the pre-operative instructions provided.

Subsequently, the surgeon (and anaesthetist, if necessary), having checked the correct planning of the operation after optimisation of erythropoiesis and the use of other strategies and techniques indicated in the pre-operative period in the three pillars of the PBM (Table I)5, examines, and, if necessary, updates the clinical documentation, the single treatment chart and the informed consent to the procedure; the same surgeon marks the site of surgery.

Before entering the operating theatre, the nurse checks the anaesthesiological instructions, administers and records the treatments prescribed (general, antibiotic, pre-anaesthesia), takes any blood samples required and informs the patient about the surgical procedure; the nurse also checks that the patient is not wearing any jewellery or removable prostheses, checks the patient’s personal hygiene (if necessary, inviting the patient to wash again before the operation), shaves the patient, when required, and cleans the area of skin involved by the operation with antiseptics.

The patient is transported to the induction/recovery room, where the surgical team (anaesthetist and surgeon) re-evaluates him or her, “signs in” the patient (using the operating theatre check-list), informs the patient, if collaborative, about the procedures that will be performed and introduces one or more devices for intravenous access. The nurse monitors the patient’s vital parameters and administers antibiotic prophylaxis; all the activities are recorded on the nursing form and on the single treatment chart

In the operating theatre the same team carries out the “time out” checks (operating theatre check-list), performs the operation and provides anaesthesia, optimises the macrocirculation, maintains homeostasis and takes samples for any intra-operative blood-chemistry tests.

In this stage the three pillars of the PBM involve the following.

Optimisation of erythropoiesis: check appropriate timing of the surgery after optimisation of erythropoiesis.

Minimisation of blood loss: ensure meticulous haemostasis and use appropriate surgical techniques; adopt blood-sparing strategies; use blood-conserving anaesthetic techniques; use autologous blood transfusion, if foreseen by the personalised PBM plan drawn up by the case manager of the Anaemia Clinic; use pharmacological strategies and haemostatic agents; use point-of-care (POC) tests.

Optimisation of tolerance of anaemia: optimise cardiac output; optimise ventilation and oxygenation; adopt restrictive transfusion thresholds.

At the end of the intervention, the surgical team carries out the “sign out” controls (operating theatre check-list) and the patient is then transferred to the induction/recovery room for post-operative observation. Here the patient is re-assessed and monitored until his or her transfer to the ward; the same team prescribes the post-operative controls and treatments that must be carried out in the ward in the first 24 hours following the operation and which also have the purpose of correctly implementing the PBM strategies included in the multidisciplinary programme of co-ordinated interventions.

Post-operative period

After the operation, the patient can be transferred to the surgical ward from which he or she came, or depending on needs and clinical conditions, can be admitted to an intensive or sub-intensive care facility.

The post-operative controls and treatments for the 24 hours following the surgical intervention are prescribed by the anaesthetist and surgeon during the period that the patient regains consciousness.

During the post-operative period, besides the management of any urgent or emergency clinical situations, the co-ordinated interventions foreseen by the multidisciplinary programme, aimed at implementing the techniques and strategies included in the three pillars of PBM and reported here, must be carried out.

Optimisation of erythropoiesis: stimulate erythropoiesis, if necessary; consider drug interactions that can cause or enhance post-operative anaemia.

Minimisation of blood losses: ensure careful monitoring of the patient and management of post-operative bleeding; guarantee fast rewarming/maintenance of normothermia (except when there is a specific indication for hypothermia); use autologous transfusion techniques if foreseen by the personalised PBM drawn up by the case manager of the Anaemia Clinic; minimise iatrogenic bleeding; manage haemostasis and anticoagulation; administer prophylaxis against upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding; give prophylaxis against infections and treat any that occur.

Optimisation of the tolerance of anaemia: optimise the tolerance of anaemia; maximise oxygen delivery; minimise oxygen consumption; adopt restrictive transfusion thresholds.

The above-mentioned strategies must be implemented throughout the post-operative period until the patient’s clinical conditions have normalised, which is when the feasibility of the patient’s discharge from hospital is evaluated. On discharge the ward doctor prepares the discharge letter and gives it to the patient. The discharge letter contains a description of the salient diagnostic-therapeutic interventions performed, information on the domiciliary management of the surgical wound and any drains, as well as the pharmacological treatment (medication reconciliation).

Healing of the surgical wound and correct compliance with the prescribed domiciliary drug treatment must be checked at each outpatient follow-up until conclusion of the post-discharge process (30 days if the patient has not had a prosthesis implanted, 1 year if prosthetic material has been implanted).

The three pillars of Patient Blood Management

Optimisation of erythropoiesis

Pre-operative period

Detection of anaemia

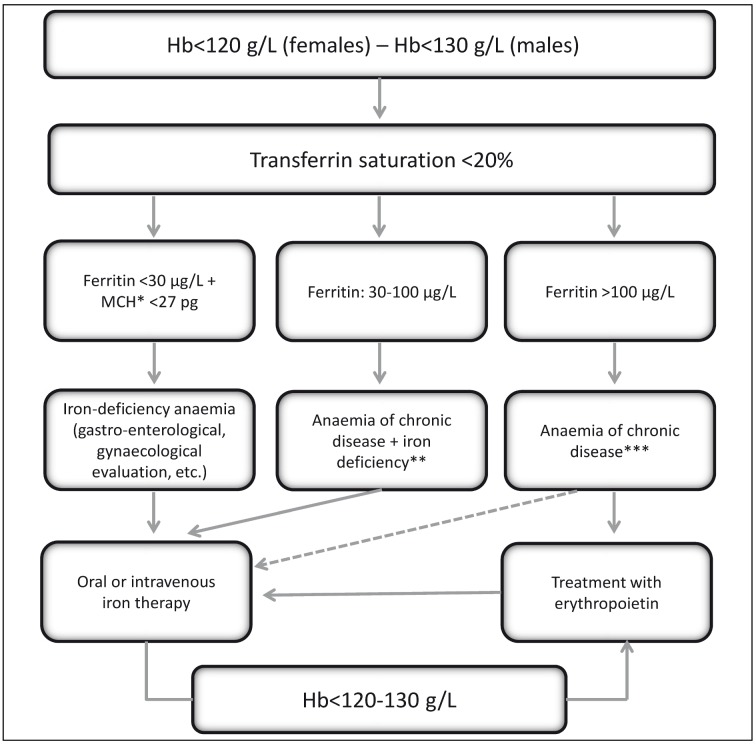

The prevalence of pre-operative anaemia in surgical patients varies greatly, ranging from 5% (among geriatric patients with hip fracture) to 75.8% (among patients with stage D colon cancer according to Dukes’ classification)15; among candidates for orthopaedic surgery associated with moderate to substantial peri-operative bleeding, such as elective joint replacement (of the hip or knee) or urgent surgery (of the hip), the prevalence of pre-operative anaemia ranges from 24±9% to 44±9%, respectively16. Epidemiological studies on anaemia in patients undergoing elective hip or knee replacement surgery showed that the anaemia is hypochromic and microcytic in between 23 and 70% of cases16. Figure 3 presents a simple algorithm for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anaemia17–19. Among the same patients the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency is about 12% and that of folate deficiency about 3%20,21. The other forms of anaemia are due to inflammatory disease, chronic kidney disease or an unknown cause22,23.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anaemia (modified from Muñoz M et al.17–19).

Hb: haemoglobin; MCH: mean corpuscular haemoglobin; The dashed arrow indicates the need to measure the ferritin level; *: The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is a relatively late indicator of iron deficiency in patients without active bleeding; in the presence of a low MCV the differential diagnosis from thalassaemia must be made; the MCV can be normal in the presence of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, post-haemorrhagic reticulocytosis, initial response to oral iron therapy, alcohol intake or myelodysplasia. ** Additional laboratory tests: reticulocyte count; creatinine; C-reactive protein. *** Additional laboratory tests to evaluate the iron deficiency: ratio between soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) and logarithm of ferritin; hypochromic red blood cells; haemoglobin content in reticulocytes.

Pre-operative anaemia, even if mild, in patients who are candidates for major surgery (not cardiac) is independently associated with a higher risk of morbidity and mortality at 30 days24. Furthermore, a recent, retrospective study demonstrated that, in the peri-operative period of patients undergoing heart surgery, the sum of two risk factors, that is anaemia (haematocrit <25%) and transfusion therapy with red cell concentrates, had a greater, and statistically significant, effect on post-operative morbidity and mortality25. Anaemia is, therefore, a contraindication to performing elective surgery.

It is recommended that elective major surgery is not performed in patients who are found to have anaemia until the anaemia has been correctly classified and treated [1B].

Anaemia is defined according to threshold values of haemoglobin (Hb) indicated by the World Health Organization (WHO)26: children up 5 years: 110 g/L; children between 5 and 12 years old: 115 g/L; children between 12 and 15 years: 120 g/L; pregnant women: 110 g/L; women who are not pregnant (aged 15 years old or more): 120 g/L; men (aged 15 years or more): 130 g/L.

It is recommended that the pre-operative assessment of the patient, aimed at detecting any anaemia and optimising erythropoiesis, is performed at least 30 days before the planned date of the operation, in order to enable more detailed diagnostic investigations and/or plan appropriate treatment [1C]6,11,12.

It is recommended that, if a state of anaemia is detected, the subsequent laboratory tests are directed at identifying iron deficiency or other nutritional deficiencies (folic acid and/or vitamin B12), chronic kidney disease and/or chronic inflammatory disorders [1C].

It is recommended that the detection and treatment of anaemia, and any further related clinical-diagnostic investigations, are included within a global PBM strategy become a standard of care for all candidates for elective surgery, especially if the risk of peri-operative bleeding is substantial [1C].

Stimulation of erythropoiesis

These recommendations concern the management of oral and intravenous iron therapy, given the paucity of studies on the use of other haematinics in the peri-operative setting27.

Since the pre-operative Hb value is the main, independent risk factor for requiring transfusion support with packed red cells, it is recommended that any nutritional deficiencies (iron, vitamin B12, folate), once detected, are treated with haematinics [1C]11.

It is suggested that the target Hb value before elective major orthopaedic surgery is at least within the normal range according to the previously cited WHO criteria [2C]11.

Oral iron therapy

In adult patients with iron-deficiency anaemia who are candidates for elective hip or knee replacement surgery, oral iron therapy, particularly if combined with restrictive transfusion protocols, has been found to be effective in the treatment of pre-operative anaemia, in limiting transfusion needs and, in some cases, also reducing the duration of time spent in hospital28–30.

It is suggested that oral iron therapy is used for the treatment of pre-operative iron-deficiency and to minimise transfusion requirements in adult patients who are candidates for elective major orthopaedic surgery [2B].

Intravenous iron therapy

The pre-operative use of intravenous iron to treat adult patients with iron-deficiency anaemia who are candidates for major surgery, including orthopaedic surgery, has been shown to be effective in correcting anaemia and limiting transfusion requirements31–33.

A recent randomised, multicentre study demonstrated the superiority (and safety) of infusion of iron carboxymaltose with respect to iron therapy per os in the correction of iron-deficiency anaemia in patients with a poor response to oral therapy34.

It is suggested that intravenous iron therapy is used for the treatment of pre-operative iron-deficiency anaemia and to limit transfusion requirements in adult patients who are candidates for elective major orthopaedic surgery [2A].

Post-operative period

Detection of anaemia

Anaemia develops in 74% of patients during hospitalisation (including those admitted with normal Hb values) and, besides causing a substantial use of resources, in part because of the prolongation of the time spent in hospital, is associated with significant increases in mortality35 and morbidity11. The prevalence of anaemia in the post-operative period in patients who have undergone elective or urgent major orthopaedic surgery is much higher, being 51% and 87%, respectively16. Furthermore, anaemia, which can be present in as many as 90% of surgical patients15, although caused mainly by peri-operative bleeding, can be worsened by repeated withdrawal of blood for laboratory tests and by ineffective erythropoiesis due to the inflammatory response induced by the surgical procedure itself36,37. This inflammation reduces the availability of iron for erythropoiesis through inhibition of its intestinal absorption and a reduction in hepcidin-mediated mobilisation of iron stores23,38–40.

The best strategy to prevent post-operative anaemia and avoid transfusions is to detect and correct any anaemia present in the pre-operative period, when possible11.

However, most adults in good health with normal baseline levels of Hb do not normally require transfusion therapy with packed red cells following a surgical intervention provided that the loss of blood during the intervention is less than 1,000 mL and the intravascular volume is maintained with crystalloids or colloids12,41.

Stimulation of erythropoiesis

Oral iron therapy

As already mentioned, the ineffective erythropoiesis caused by the post-operative inflammatory response36,37, which inhibits intestinal absorption of iron and reduces the mobilisation of iron stores, makes oral iron therapy unfeasible in the post-operative period23,38–40.

Indeed, various randomised studies have demonstrated that oral iron therapy in patients undergoing elective or urgent orthopaedic surgery is not only not effective at correcting the post-operative anaemia and reducing transfusion requirements, but is also often associated with the development of adverse events42–44.

Oral iron therapy is not recommended for the treatment of post-operative anaemia and minimisation of transfusion needs in patients undergoing elective or urgent major orthopaedic surgery [1B].

Intravenous iron therapy

Intravenous administration of iron in the post-operative period, in patients who have undergone lower limb arthroplasty45,46 or correction of scoliosis47, is effective at correcting anaemia and limiting transfusion needs.

It is suggested that intravenous iron therapy is used for the treatment of post-operative anaemia and to limit transfusion needs in patients undergoing elective major orthopaedic surgery [2C].

Short-term management in the peri-operative period

Stimulation of erythropoiesis

Iron therapy

In orthopaedic patients with hip fractures, the short-term use of intravenous iron and adoption of restrictive transfusion strategies were demonstrated to be effective in limiting transfusion requirements, particularly in non-anaemic patients48–50; other studies, in anaemic patients, showed that intravenous iron was more effective if combined with recombinant human erythropoietin51,52.

Similar results were obtained in patients undergoing knee replacement surgery53. Recently a large, observational study in patients who underwent elective lower limb arthroplasty or urgent surgery for hip fracture further confirmed the above described results: short-term infusions of iron were found to be effective with or without concomitant treatment with erythropoietin54.

Short-term treatment with intravenous iron is suggested in order to minimise transfusion requirements in adult patients undergoing elective major orthopaedic surgery who are at risk of severe anaemia in the post-operative period [2B].

Dose of iron therapy

Oral iron

A recently published randomised clinical trial in critically ill patients with iron-deficiency anaemia demonstrated that 65 mg of elemental iron/die per os are effective at reducing transfusion requirements.

A dose of 100 mg of elemental iron/die for 2–6 weeks prior to the surgical intervention is recommended for the treatment of pre-operative anaemia [1C]55.

Intravenous iron

It is suggested that the dose of intravenous iron needed to replenish iron stores is calculated using Ganzoni’s formula19,56: “total iron requirements (mg) = [desired Hb – actual Hb (mg/dL)] × weight (kg) × 0.24 + 500 mg (for iron stores)” [2C].

The therapeutic regimen to adopt varies depending on the formulation of iron used.

It is suggested administering 200 mg of elemental iron intravenously for every 500 mL of blood lost [2C]27.

Safety of intravenous iron therapy

Numerous studies performed in thousands of patients in different clinical settings have demonstrated the safety of intravenous iron therapy57,58. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recently published “New recommendations to manage risk of allergic reactions with intravenous iron-containing medicines”59. A year later, in 2014, Rampton et al. published guidelines for the management of hypersensitivity reactions to intravenous iron60.

According to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the EMA: a) intravenous iron-based medicines should be used when oral iron cannot be used or does not work, particularly in patients in dialysis, in the peri-operative period, or in the presence of disorders of gastrointestinal absorption; b) the benefits of intravenous iron outweigh its risks, provided that appropriate measures are taken to minimise the possibility of allergic reactions; c) the data on the risk of hypersensitivity come mainly from spontaneous post-marketing notifications and the total number of deaths or life-threatening events is low; d) these data cannot be used to pick up any differences in the safety profile of the various iron-containing preparations.

The CHMP of the EMA has also produced the following recommendations for healthcare staff, with the aim of improving patients’ safety.

Intravenous iron must only be administered when “staff trained to evaluate and manage anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions” and “resuscitation facilities” are immediately available.

A test dose is no longer recommended.

If a hypersensitivity reaction occurs, “healthcare professionals should immediately stop the iron administration and consider appropriate treatment for the hypersensitivity reaction”.

“Patients should be closely observed for signs and symptoms of hypersensitivity reactions during and for at least 30 minutes following each injection of an intravenous iron medicine.”

Intravenous iron is contraindicated in patients with hypersensitivity to the active substance or excipients or to other iron-containing products administered parenterally.

The risk of hypersensitivity is increased “in patients with known allergies or immune or inflammatory conditions and in patients with a history of severe asthma, eczema or other atopic allergy.”

“Intravenous iron products should not be used during pregnancy unless clearly necessary” and their use “should be confined to the second or third trimester, provided the benefits of treatment clearly outweigh the potential serious risks to the foetus such as anoxia and foetal distress.”

As far as concerns the safety of intravenous iron, Auerbach and Macdougall state that, based on all retrospective and prospective studies, provided that high molecular weight iron dextran is avoided, which is no longer on the market, all the other preparations are safe and probably much safer than most doctors perceive58,61.

In contrast, as far as concerns the risk of infections the data currently available in the literature do not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn and, for this reason, it is suggested that intravenous iron therapy is avoided in patients with acute infections [2C]27,57.

It is suggested that intravenous iron is not administered to patients with ferritin values >300–500 ng/mL and with a transferrin saturation >50% [2C]27.

Use of erythropoietin in the peri-operative period

There are two possible strategies for the use of erythropoietin in the peri-operative period12: the erythropoietin can be administered to optimise autologous donation, in the very few cases in which autologous donation is indicated, or it can be used in patients who are candidates for elective surgery who cannot complete a predeposit programme, in the very few cases in which such a programme is indicated. However, the prescription of erythropoietin α, β and z is currently paid for by the National Health Service if used as a treatment to increase the amount of autologous blood in the setting of a pre-operative deposit programme, with the limitations set out in the technical data sheet. Erythropoietin α can also be charged to the National Health Service when prescribed to reduce allogeneic transfusions in adults patients who are candidates for elective major orthopaedic surgery considered to involve a high risk of complications requiring transfusion, for which a pre-operative autologous blood donation programme is not available.

Erythropoietin has been found to be effective in limiting transfusion requirements in candidates for lower limb elective joint replacement surgery62–64, although the costs are unacceptable65.

It is suggested that erythropoietin is administered to adult candidates for elective major orthopaedic surgery who undergo a pre-deposit programme in which the donation of at least three units of whole blood is planned or for which a pre-deposit programme is not available and it is expected that the blood loss will be greater than 1,000 mL [2B].

In order to avoid a “functional deficiency” of iron during treatment with erythropoietin, it is suggested that intravenous iron is administered [2B]12,66–69.

Minimisation of blood loss

Pre-operative period

Pre-deposit

Pre-deposit autologous blood transfusion consists in collecting units of blood from the patient (pre-deposit), storing them (without fractionation) and using them exclusively for the patient-donor. It has been widely shown that pre-depositing blood increases the risk of requiring transfusion therapy, including allogeneic transfusions70.

In adult candidates for elective major orthopaedic surgery, it is recommended that the practice of pre-deposit is limited to subjects with rare red blood cell groups or complex alloimmunisation, for whom it is impossible to find compatible blood components [1A]12,69.

In any case, there is no need for autologous blood collection if the patient’s basal Hb is such that, considering peri-operative losses, a stable, post-operative Hb of 100 g/L or more can be expected.

Contraindications to the collection of autologous blood are:

- Hb values lower than the threshold values indicated by the WHO to define anaemia [children up 5 years: 110 g/L; children between 5 and 12 years old: 115 g/L; children between 12 and 15 years: 120 g/L; pregnant women: 110 g/L; women who are not pregnant (aged 15 years old or more): 120 g/L; men (aged 15 years or more): 130 g/L]26;

- severe heart disease;

- positivity for one of the following tests, the results of which must be known before starting the autologous pre-deposit programme: HBsAg, anti-HCV antibodies, anti-HIV 1–2 antibodies;

- epilepsy;

- ongoing bacteraemia.

However, even in the presence of criteria for exclusion from autologous blood collection, a patient can, exceptionally, be accepted if the indications are appropriate and there are specific, documented clinical circumstances motivating the recourse to autologous donation.

It is recommended that the interval between collecting one unit of autologous blood and the next is at least 7 days and that, in all cases, the last unit is collected at least 7 days before the planned operation [1C]71–76.

Identifying and managing the risk of bleeding

The second pillar of PBM includes all the strategies to minimise bleeding and preserve the individual blood reserves.

These strategies are applied right from the pre-operative stage, through the definition of parameters to stratify bleeding risk, that is, a detailed history and thorough clinical examination. Much care must be given to the patient’s drug history, since the number of patients being treated with antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, anti-inflammatory drugs and antidepressants or herbal products with antiplatelet effects is increasing continuously.

Recent guidelines (British, Australian and Italian)12,77–79 recommend the use of structured questionnaires to reduce bleeding and preserve individual blood reserves through the identification of patients at risk of bleeding and for a potential quantification of the bleeding risk in patients with congenital clotting disorders80.

In fact, in the context of pre-operative screening, a standardised questionnaire covering the patient’s clinical and drug history seems to be superior to an assessment based only on the results of common laboratory tests [activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), prothrombin time /International Normalized Ratio (PT/INR), platelet count]81.

The second important element is the physical examination of the patient, which is aimed at detecting any signs of cutaneous bleeding (petechiae, ecchymoses, haematomas) which could suggest the presence of liver disease, a congenital clotting disorder or platelet disorder82.

Although various guidelines recommend the use of standard laboratory tests (aPTT, PT, platelet count) in the pre-operative period to define the bleeding risk77,79,83, a systematic review demonstrated that altered coagulation screening tests in the pre-operative period are not predictive of intra- or post-operative bleeding84. However, given their low cost and for reasons of prudence, the guidelines of the Italian Society for the Study of Haemostasis and Thrombosis (SISET) suggest that these tests are performed79.

Low plasma levels of fibrinogen seem to be predictive of an increased risk of intra-operative bleeding in heart surgery85.

Results of clotting tests performed in the pre-operative period with point-of-care (POC) instruments do not predict bleeding during or after surgery86,87, whereas monitoring haemostasis by POC instruments during the intra-operative phase is useful for assessing the causes of bleeding.

Although there are reports on possible correlations between some haemostasis-related genetic polymorphisms or mutations and an increased risk of surgical bleeding, at present it is not possible to assign a clear predictive value to genetic tests88.

Platelet function can be assessed through the use of several analysers (PFA 100/200, CPA Impact-R, MEA Multiplate, PlateletWorks, VerifyNow), which have a varied sensitivity for the different antiplatelet drugs. However, given the variability and poor standardisation of tests to determine platelet function, the SISET guidelines do not recommend their routine use prior to surgery79. However, the guidelines of the European Society of Anaesthesiology suggest evaluating platelet function in the case of a positive history of bleeding and in the case of known alterations in platelet function because of congenital disorders or medication use88.

Correct pre-operative management of the bleeding risk in surgical patients involves appropriate interventions to acquired factors (drugs, diseases) or congenital conditions predisposing to bleeding.

It is recommended that a careful personal and family history is taken from the patient in order to pick up any bleeding risk, information about ongoing medication use or the consumption of any over-the-counter or herbal products, because this assessment is considered more informative of peri-operative bleeding risk than isolated evaluation of results of pre-operative screening coagulation tests [1C].

It is suggested that the platelet count, PT and aPTT are determined before every surgical intervention or invasive procedure that carries a risk of bleeding [2C].

In the case of a positive history of bleeding, it is suggested that an expert in haemostasis is consulted in order to diagnose possible bleeding syndromes [2C].

Minimising iatrogenic blood loss and planning the procedure

Management of antiplatelet treatment

It is known that cyclo-oxygenase-2-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not responsible for increased bleeding during total knee or hip replacement89–91 and, for this reason, it is not necessary that the use of these drugs is suspended before elective lower limb arthroplasty. In contrast, ibuprofen, diclofenac and indomethacin significantly increase blood loss during total knee replacement surgery92, and so the use of these drugs should be suspended.

Monotherapy with aspirin (ASA) or clopidogrel does not need to be stopped before urgent orthopaedic surgery nor is it necessary to delay surgery in patients taking these drugs93,94.

According to a recent Italian intersociety consensus statement95 ASA, if taken for primary prevention, should be suspended 7 days before elective arthroplasties whereas it should be stopped on admission to hospital in the case of fracture of the femoral neck. If it is being taken for secondary prevention (i.e., in a patient who has had a previous cardiovascular event), it should be continued in the peri-operative period at a dose of 75–100 mg/die.

It is suggested that cyclo-oxygenase-2-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are not suspended prior to elective lower limb joint replacement surgery [2B].

It is suggested that ibuprofen, diclofenac and indomethacin are suspended prior to elective lower limb joint replacement surgery [2B].

It is recommended that ASA monotherapy, being taken for secondary prevention, is not suspended before elective lower limb joint replacement surgery [1B].

Ticlopidine and clopidogrel belong to the family of thienopyridines, being first- and second-generation examples, respectively; both inhibit ADP-induced platelet activation by binding to the P2Y12 receptor. Prasugrel is a third-generation thienopyridine, which must be converted to its active metabolite before binding to the P2Y12 platelet receptor. Thienopyridines have much stronger antiplatelet activity than ASA.

Various studies have described peri-operative bleeding complications in association with the use of clopidogrel and the risk of bleeding can increase when clopidogrel is given together with ASA. At present, there are no data available on the use of prasugrel in the peri-operative period; the platelet inhibition induced by this drug lasts at least 7 days88.

Ticagrelor, another antiplatelet agent, unlike the thienopyridines, has a direct effect on the P2Y12 receptor, without requiring biotransformation by the P450 cytochrome; it has a rapid onset of action and the platelet inhibition decreases to 10% after about 4.5 days96.

Since clopidogrel and prasugrel are responsible for peri-operative bleeding, it is recommended that these drugs are suspended 5 and 7 days, respectively, before surgery, in cases of increased bleeding risk [1C].

It is suggested that ticagrelor is suspended 5 days pre-operatively [2C].

Patients with acute coronary syndrome or those undergoing angioplasty benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy with a combination of ASA and another platelet anti-aggregant drug (thienopyridine or ticagrelor), even if this increases the risk of bleeding complications97.

In the case of urgent or emergency surgery, it is recommended that the decision regarding the continuation of treatment with antiplatelet drugs in the peri-operative period is the result of a multidisciplinary evaluation [1C].

It is suggested that urgent or emergency surgical interventions are performed, maintaining dual antiplatelet therapy (ASA/clopidogrel; ASA/prasugrel; ASA/ticagrelor) or at least ASA, when the bleeding risk is high [2C].

Oral dual antiplatelet therapy is necessary for patients with stents, in whom the suspension of one or both of the anti-aggregant drugs, particularly in the first months after the procedure, carries a significant risk of thrombosis of the stent, which is a potentially fatal event98. The growing number of coronary artery revascularisation procedures carried out each year is inevitably leading to an increase in the number of patients with coronary artery stents who must undergo surgical interventions. The management of antiplatelet therapy in these patients is often arbitrary, despite it being a critical factor in the prevention of ischaemic-haemorrhagic complications.

It is recommended that elective orthopaedic surgery is not performed during the first 3 months after implantation of a metal stent or during the first 12 months after implantation of a drug-eluting stent [1C].

Management of anticoagulant therapy

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) are used for the prophylaxis or treatment of thromboembolic events, particularly in patients with mechanical heart valves, atrial fibrillation or a past history of venous thromboembolism. It is not always necessary to suspend the use of these drugs and the decision depends on the type and site of the operation or invasive procedure88,99,100.

In patients with a low/medium risk of thromboembolism, it is suggested that VKA treatment is suspended 5 days before the planned elective joint replacement surgery and bridging therapy is established [administering low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) at prophylactic doses] in the following way: last dose of VKA on day −5; first subcutaneous dose of LMWH once a day, starting on day −4 if the patient was being treated with acenocoumarol, and starting on day – 3 if the patient was being treated with warfarin [2C].

In patients at high risk of thromboembolism [i.e., with atrial fibrillation and a CHADS2 (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 years, Diabetes mellitus, prior Stroke or transient ischaemic attack or thromboembolism) score >2; with recurrent venous thromboembolism treated for less than 3 months; with a mechanical heart valve] it is recommended that bridging therapy (LMWH at therapeutic doses) is given in the following manner: last dose of the VKA on day −5; first subcutaneous dose of LMWH twice daily starting from day −4 if the patient was being treated with acenocoumarol, and starting from day −3 if the patient was being treated with warfarin [1C].

An Italian study demonstrated the efficacy and safety of using reduced therapeutic doses (65–70 IU/kg twice daily) instead of the classical bridging therapy with 100 IU/kg twice daily100.

It is suggested that the last dose of LMWH is administered 12 hours before a planned operation and/or invasive procedure, except when a full dose of anticoagulant is being used, in which case an interval of 24 hours is suggested [2C].

The new oral anticoagulants

Dabigatran etexilate is an oral inhibitor of thrombin. It has a half-life of 14–17 hours, is eliminated mostly (80%) in the urine, does not interact with food and does not necessitate blood tests for monitoring. It is indicated for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in major orthopaedic surgery, for the prevention of emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation and in the treatment and secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism101–105.

Rivaroxaban and apixaban are oral inhibitors of activated factor X (FXa). They have half-lives of 9–12 hours and 10–15 hours, respectively; rivaroxaban is eliminated mainly through the kidneys (although only half in an active form), while apixaban is eliminated partly through the hepatic route and partly in the urine. Both are indicated for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in major orthopaedic surgery, for the prevention of emboli in patients with atrial fibrillation and for secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism106–113.

The management of new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) use during surgical interventions is based largely on the consensus of opinions of experts, although the experts have produced contrasting advice, particularly with regards to the indication for and duration of bridging therapy with parenteral anticoagulants, which is proposed by some experts also for patients being treated with NOAC. Indeed, this is the strategy suggested by the recent guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology88. Some scientific societies have suggested indications for suspending or not suspending treatment with NOAC114. Based on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics characteristics of NOAC, a temporary (short-term) suspension of these drugs is possible without requiring bridging therapy, which would expose the patient to a higher risk of bleeding, as demonstrated by recent registry data115. For this reason the following recommendations and suggestions reflect the literature data and recent guidelines of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), which do not include the use of bridging therapy114,116–118.

Table II shows the stratification of bleeding risk in relationship to invasive procedures or surgical interventions: the bleeding risk is defined as “clinically unimportant”, “low” or “high”114.

Table II.

Classification of elective surgical interventions divided according to bleeding risk. (Modified from Heidbuchel H et al.114)

Interventions with a clinically unimportant risk of bleeding:

|

Interventions with a low risk of bleeding:

|

Interventions with a high risk of bleeding:

|

It is suggested that NOAC (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) are not suspended and that the operation is performed 12–24 hours (depending on whether the drug is administered, respectively, once or twice a day) after the last dose in the case of: dermatological surgery, dental procedures, gastroscopy and colonoscopy (without biopsies), ocular interventions (particularly of the anterior chamber, such as cataract surgery) and operations involving a clinically unimportant risk of bleeding (see Table II) [2C]114.

It is suggested that NOAC are suspended 24 hours before elective surgery that carries a low risk of bleeding, in patients with normal renal function [creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≥80 mL/minute] [2C].

It is suggested that NOAC are suspended 48 hours before elective surgery that carries a high risk of bleeding in patients with normal renal function (CrCl ≥80 mL/minute) [2C].

In patients with impaired renal function, the suspension of the NOAC should be graduated according to the type of drug and the CrCl, as indicated in Table III114.

Table III.

When to suspend treatment with new oral anticoagulants before surgery on the basis of the patient’s renal function (determined by creatinine clearance [CrCl]) and bleeding risk (low or high, see Table II) associated with the surgical procedure. (Modified from Heidbuchel H et al.114)

| CrCl (mL/minute) | Bleeding risk associated with the surgical procedure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| New oral anticoagulants | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Dabigatran | Apixaban | Rivaroxaban | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |

| ≥80 | ≥24 h | ≥48 h | ≥24 h | ≥48 h | ≥24 h | ≥48 h |

| 50–80 | ≥36 h | ≥72 h | ≥24 h | ≥48 h | ≥24 h | ≥48 h |

| 30–50 | ≥48 h | ≥96 h | ≥24 h | ≥48 h | ≥24 h | ≥48 h |

| 15–30 | NI | NI | ≥36 h | ≥48 h | ≥36 h | ≥48 h |

| <15 | NI | |||||

CrCl: creatinine clearance; h: hours; NI: use of drug not indicated.

It is suggested that rivaroxaban and apixaban are suspended 36 or 48 hours before surgery with a low or high bleeding risk, respectively, in patients with a CrCl between 15–30 mL/minute; that dabigatran is suspended 36 or 72 hours before surgery with a low or high bleeding risk, respectively, in patients with a CrCl between 50–80 mL/minute; and that dabigatran is suspended 48 or 96 hours before surgery with a low or high risk of bleeding respectively, in patients with a CrCl between 30–50 mL/minute [2C].

New oral anticoagulants and laboratory tests

The NOAC do not require routine monitoring through coagulation tests; in any case, global tests, such as the PT and aPTT, are not useful for quantifying the anticoagulant effect of these new drugs and other quantitative tests are not yet available for routine use in all hospitals. Furthermore, POC instruments to determine the INR should not be used in patients being treated with NOAC. However, in emergencies (severe haemorrhage, thrombotic events, urgent surgery, liver or kidney failure, suspected overdose or pharmacological interactions) it may be necessary to quantify and have a rough idea of the anticoagulant effect of NOAC through the available coagulation tests; in these cases it is extremely important to know precisely when the drug was taken with respect to the blood sample, since the maximum effect of NOAC occurs at the time of their peak plasma concentration, which is reached 1–3 hours after drug intake114. Thus, for a correct clinical interpretation of the laboratory data, it is essential to know the type of drug taken, the dose and the time the last dose was taken.

At present, there is still no definitive information on whether assays prior to taking the next dose (trough concentration) or at the time of the peak plasma concentration are better indicated. Analyses carried out in the USA by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the phase III studies “Re-LY” and “ROCKET AF” showed that the trough drug level was correlated with clinical events. On the basis of this evidence, it has been proposed that controls should be performed before the patient takes the next dose of the drug (trough concentration).

Both first and second level clotting tests are variably affected by the different anticoagulant drugs. In general, it can be stated that the PT and chromogenic tests for assaying anti-FXa activity are more influenced by anti-FXa drugs (rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban), whereas the aPTT, thrombin time, ecarin clotting time and ecarin chromogenic assay are more affected by drugs that inhibit thrombin (dabigatran).

Two coagulation tests for evaluating the anticoagulant effect of the direct inhibitors of thrombin, such as dabigatran, have so far been identified in the literature: the aPTT and the diluted thrombin time. Alterations of these tests can be indicative of an increased bleeding risk119,120. While the aPTT only provides a qualitative assessment and there is great variability between the different reagents on the market, the diluted thrombin time is able to provide a quantitative evaluation of the level of dabigatran present in the circulation and, considering its relative simplicity, should be used.

The inhibitors of FXa, such as rivaroxaban, cause a prolongation of the PT although this provides only approximate information, given the wide variability of results depending on the type of reagent used121.

An anti-FXa chromogenic test, using calibrators that are readily available on the market, has recently been developed. It is, however, important to clarify that, at present, these new tests (diluted thrombin time, for dabigatran, and anti-FXa activity assay, for the inhibitors of FXa) can provide plain information on the absence of the anticoagulant in the circulation, while there is not a clear, defined relationship between the circulating level and risk of bleeding or thrombosis. This aspect must be studied in the coming years.

At present we know that the concentrations of the different oral anticoagulants can be measured using tests that are specific and sensitive for the individual compounds: these tests are simple, cheap and can be performed in all laboratories. We also know that information regarding the concentration of the anticoagulant drugs in the blood is useful for managing patients who are being assessed for particular clinical situations, such as urgent or elective surgery, invasive procedures, and haemorrhagic or thromboembolic complications. Furthermore, in the same way as for VKA, the results of these tests could be useful in the near future for determining threshold levels of anticoagulation above which surgery, invasive procedures and thrombolysis are contraindicated. Currently, one of the most important practical problems is the limited number of Italian laboratories able to carry out these specific tests; however, the growing use of NOAC and the consequent increase in the clinical needs of treated patients should lead to a progressively greater use of these tests in various different hospital settings.

No evidence-based recommendations can be made on the use of laboratory tests in the pre-operative evaluation of the anticoagulant effect of the NOAC.

The management of patients with comorbidities related to altered haemostasis

Patients with endocrine, metabolic or systemic diseases, such as FX deficiency in amyloidosis, can have altered haemostasis with a tendency to bleeding, similar to that in patients with congenital deficiencies of clotting factors122,123. The treatment strategy for these coagulopathies is frequently unclear.

It is suggested that the treatment of patients with altered haemostasis related to systemic, metabolic or endocrine diseases is established through consultation with an expert in haemostasis and thrombosis [2C].

Other drugs, besides antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, valproic acid and Ginkgo biloba, can interfere with haemostasis, predisposing to bleeding.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been associated with an increased tendency to bleed, due to depletion of serotonin from platelets124; however, the transfusion requirements of patients being treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors who underwent major orthopaedic surgery or heart surgery were not increased125,126.

In some cases valproic acid (an anti-epileptic drug) can lead to a reduction in the levels of some clotting factors [FVII, FVIII, FXIII, von Willebrand factor (vWF), fibrinogen], platelets, protein C and antithrombin127; however, these changes did not cause bleeding complications128,129.

As far as concerns the extract of Ginkgo biloba, a meta-analysis of 18 randomised, controlled trials did not show an increase in bleeding associated with daily, oral intake of this medicinal plant130.

It is suggested that treatment with selective serotonin release inhibitors is not routinely suspended in patients undergoing surgery [2B].

When selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are used together with antiplatelet agents, it is suggested that the patient is assessed individually to define the strategy to adopt prior to surgery [2C].

In the case of surgery, it is suggested considering, on an individual basis and with specialist advice, the suspension of treatment with valproic acid, because this drug can promote bleeding [2C].

It is recommended that the use of Ginko biloba extract is not suspended in the case of surgical interventions [1B].

Management of the patient with a congenital bleeding disorder

Defects of primary haemostasis

The most common congenital bleeding disorder is certainly that of hereditary deficiency of vWF, which has prevalence of 0.6–1.3% in the population13,131. The disease is due to either a lack of vWF or dysfunction of the protein and is classified into three types: type 1: partial quantitative defect; type 2: qualitative defect, of which there are four variants: 2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N; and type 3: total lack of vWF. The acquired form of von Willebrand’s disease (vWD) is the result of autoimmune and/or neoplastic disorders, or has a drug-based aetiology132.

The bleeding tendency is a consequence of altered platelet adhesion because of a lack or dysfunction of vWF and/or reduced levels of FVIII13,131,132.

Given that the laboratory diagnosis of vWD is complex, the laboratory tests must always be guided by the patient’s clinical history and physical examination. Additionally, there are questionnaires and bleeding scores that have been specifically designed to evaluate and quantify bleeding risk133–135.

The prevention and management of bleeding in vWD is based on three treatment strategies: administration of desmopressin, which induces mobilisation of vWF from endothelial storage sites (stimulation therapy); administration of plasma-derived concentrates of vWF or vWF-rich FVIII (replacement therapy); administration of antifibrinolytics or platelet transfusions (haemostatic therapy). There are numerous national and international guidelines on this subject13,131,136–140.

It is recommended that patients with vWD are managed in the pre-operative period in collaboration with an expert in haemostasis and thrombosis [1C].

It is recommended that criteria are used to define and evaluate bleeding risk in patients with vWD [1C].

It is recommended that patients with vWD who are to undergo minor surgery and are expected to have mild bleeding are given desmopressin, after a trial test, at doses explained in specific guidelinese (0.3 μg/kg diluted in 50 mL of saline solution and infused slowly, over more than 30 minutes) [1C]136–140.

It is recommended that patients with vWD who are to undergo major surgery and are expected to have clinically relevant bleeding are given replacement therapy with plasma-derived vWF or vWF-rich FVIII, using the treatment regimens explained in the specific guidelines [1C].

In patients with vWD who are to undergo major surgery, it is suggested that antifibrinolytics, as an adjuvant to more specific treatments, and platelet transfusions are used only in the case of failure of other treatments [2C].

In the context of disorders of primary haemostasis, platelet dysfunction is a diagnostic challenge. There does not seem to be a correlation between the severity of bleeding, the degree of vWF/platelet dysfunction and diagnostic laboratory tests, so that disorders of platelet function constitute a risk factor for bleeding rather than an unequivocal cause.

The use of platelet function tests with the PFA 100/200 cannot be recommended in patients with defects of primary haemostasis because of the poor sensitivity of the tests as well as false positive and false negative results141–143.

The most common and least severe platelet disorders respond well to desmopressin, which shortens the bleeding time, whether used as prophylaxis or for the treatment of bleeding144–146. When used, the standard dose is 0.3 μg/kg, diluted in 50 mL of saline solution and infused slowly, over more than 30 minutes144.

Antifibrinolytics are useful as an adjunctive therapy in platelet disorders; small bleeds, such as those occurring in dental surgery, can respond well to these agents, even when used alone. The use of antifibrinolytic agents for the treatment of hereditary platelet disorders is not, however, based on evidence, although tranexamic acid (TXA) can partially correct the effects of clopidogrel on primary haemostasis142,144,147,148.

In patients with hereditary disorders of platelet function, it is suggested that desmopressin is used for the prevention and control of bleeding, and that TXA is used as an adjuvant [2C].

The best known congenital platelet disorders are Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia and Bernard-Soulier syndrome. These are characterised, respectively, by defective platelet aggregation and adhesion, due to alterations in platelet membrane glycoproteins (GP IIb/IIIa in Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia and GP Ib-IX in Bernard-Soulier syndrome).

In most patients with these disorders, mild mucocutaneous bleeding responds to treatment with antifibrinolytic agents. However, the use of recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) is indicated for surgery and invasive procedures (including dental extractions, sometimes), even if the technical data sheet states that it is indicated only for those patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia who have antibodies to GPIIb/IIIa and/or human leucocyte antigens or have become refractory to platelet transfusions149,150.

When used, rFVIIa should be administered at a dose of 90 μg/kg, immediately before the intervention, repeated every 2 hours for the first 12 hours and, subsequently, every 3–4 hours until the bleeding risk has disappeared151.

However, there are no universally accepted doses of rFVIIa defined for the various different settings of use. rFVIIa is not indicated in other forms of platelet disorders, for which platelet transfusions are necessary.

It is recommended considering the use of rFVIIa in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia who are to undergo surgical interventions [1C].

In patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia or Bernard-Soulier syndrome undergoing elective, major surgery, it is suggested that platelet concentrates are transfused when other therapeutic options, including rFVIIa, do not guarantee a therapeutic effect [2C]142,145.

It is suggested that the first doses of platelets are administered immediately before the intervention and further doses given after it, depending on clinical need [2C].

In cases of urgent surgery, single-unit platelet concentrates can be given, despite the awareness of the high risk of alloimmunisation and the consequent, subsequent limitation of response to this treatment145.

As far as concerns treatment, the hereditary platelet disorders are considered moderate platelet disorders and, in the absence of platelet dysfunction, should be treated on the basis of the platelet count. Guidelines on platelet transfusions suggest a threshold of 50×109 platelets/L for major surgery or invasive procedures152–155 [liver biopsy, laparotomy, diagnostic lumbar puncture, insertion of central venous catheters (recent North-American guidelines suggest a threshold of 20×109 platelets/L for this last procedure)]155 and a threshold of 100×109 platelets/L for neurosurgical or ophthalmological interventions152–154. However, there is still insufficient evidence to recommend a threshold for prophylactic transfusions in the peri-operative period in patients with hereditary platelet disorders.

It is recommended that platelet transfusion are not used routinely in patients with hereditary platelet disorders [1C].

In patients with hereditary platelet disorders no evidence-based recommendations can be made concerning the threshold to adopt in the peri-operative period for prophylactic transfusion therapy with platelet concentrates.

Defects of haemostasis related to clotting factor deficiencies

Congenital deficiency of FVIII and FIX in the plasma causes haemophilia A and haemophilia B, respectively.

The prevalence of haemophilia A in the population is 1:10,000, while that of haemophilia B is 1:60,000. The clinical manifestations of haemophilia are spontaneous bleeding, mainly within joints, and excessive bleeding in the case of trauma and/or surgical interventions. The severity of the bleeding is related to the extent of the factor deficiency. Both forms of haemophilia are classified as mild, moderate or severe, depending on the level of FVIII or FIX present.

In the severe forms of haemophilia, replacement therapy can lead to the development of antibodies against FVIII or FIX, known as “inhibitors”, a critical circumstance that requires various therapeutic strategies.

Anti-FVIII autoantibodies cause the bleeding disorder known as acquired haemophilia, which is rare condition characterised by a predisposition to potentially dangerous bleeding. This disorder is usually associated with cancer, autoimmune disorders, drugs or pregnancy.

The treatment of haemophilia is essentially replacement therapy with plasma-derived or recombinant concentrates of the deficient clotting factor (FVIII or FIX). Mild haemophilia A can also be treated with desmopressin and TXA, instead of replacement of the deficient factor with concentrates.

Despite the wide variability in the doses of concentrates used for the prophylaxis or treatment of bleeding, in the case of surgery, the World Federation of Haemophilia recommends that the levels of the deficient factor are 80–100% in the pre-operative period156; it also recommends that the levels are maintained around 60–80% in the first 3 days after the operation, around 40–60% for the next 3 days and around 30–50% in the second week after surgery.

In the case of haemophilia B, the recommended factor levels are slightly lower: 60–80%, 40–60%, 30–50% and 20–40%, respectively140,156–162.

In conclusion, the recommendations for the management of patients with haemophilia or other congenital bleeding disorders are the following.

Collaboration with an expert in haemostasis and thrombosis is recommended during the planning of the surgical intervention [1C].

It is recommended that adequate replacement therapy is given during the peri-operative period [1C].

It is suggested that guidelines on how to perform replacement therapy (target level of deficient factor and duration of treatment) are followed for patients who are candidates for elective surgery [2C].

With regards to replacement therapy in the peri-operative period, it is recommended that either recombinant or plasma-derived concentrate is used [1C].

In the presence of inhibitor, treatment with rFVIIa or activated prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC), i.e. a factor eight inhibitor bypassing agent (FEIBA), is suggested [2C].

A recent, prospective study carried out on 24 haemophilic patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery showed the presence of subclinical deep vein thromboses in over 10% of cases. On the basis of these results, antithrombotic prophylaxis could also be indicated in haemophilic patients, in individual cases. Many Haemophilia Centres in Europe use pharmacological antithrombotic prophylaxis after orthopaedic surgery163.

For haemophiliacs undergoing major surgery, it is suggested that peri-operative thromboprophylaxis is individualised [2C].

Congenital deficiencies of clotting factors other than FVIII and FIX are very rare and have a prevalence of between 1:500,000 and 1:2,000,000164; the prevalence of autosomal dominant FXI deficiency is 1:30,000, but the most common of these deficiencies is that of FVII.

The levels of evidence on treatment of these deficiencies are low (descriptive studies and experts’ opinions) and data on pre-operative prophylactic therapy are scarce.

In cases of major surgery in patients with FVII deficiency, the proposed threshold for replacement therapy with FVII concentrate is 10% of the normal plasma level164–166. Above this level replacement therapy does not seem to be necessary, as demonstrated by a retrospective analysis of surgical procedures conducted without giving such therapy and during which the frequency of bleeding events was 15%167.

rFVIIa is the treatment of choice for congenital FVII deficiency; if this is not available, a plasma-derived concentrate of FVII is preferable to PCC, because of the potential prothrombotic effect of the latter140,164.

In congenital FVII deficiency, as an alternative to rFVIIa, it is suggested that a plasma-derived concentrate of FVII is used at the dose of 10–40 IU/kg [2C]164.

In patient with congenital FVII deficiency who are to undergo major surgery, it is suggested using a dose of rFVIIa of 15–30 μg/kg every 4–6 hours, usually giving at least three doses [2B]164.

In cases of congenital deficiency of fibrinogen or FXIII the British guidelines recommend using specific concentrates164. Replacement therapy is indicated in hypofibrinogenaemia when the concentration of fibrinogen is <1 g/L or <20–30% of normal. However, the possible risk of thrombosis must be kept in mind when using plasma-derived concentrates.

Fresh-frozen plasma, preferably industry-produced and virus-inactivated, is the only therapeutic option in patients with congenital FV or FXI deficiency164. There is a plasma-derived concentrate of FXI on the market, but it is not currently available in Italy. Patients with FXI deficiency and inhibitors have been treated with success, on the occasion of surgery, with low doses of rFVIIa (33–47 μg/kg)168; contemporaneous administration of TXA has also been demonstrated to be effective in controlling bleeding164.

PCC are the reference concentrates for deficiencies of FII and FX, for which specific concentrates are not available164,169,170.

In patients with other clotting factor deficiencies, no evidence-based recommendations can be made on the peri-operative use of rFVIIa, desmopressin or TXA.

Management of patients with acquired platelet disorders

To reduce the risk of bleeding associated with major surgery or invasive procedures in patients with acquired platelet disorders, it is suggested that a prophylactic transfusion of platelet concentrates is given if the platelet count is below the threshold of 50×109 platelets/L [2C]152–155.

It is suggested that the first doses of platelets are given immediately before the operation and further doses after it, depending on the clinical need [2C].

Intra-operative period

Autologous transfusion techniques

Acute normovolaemic haemodilution

Acute normovolaemic haemodilution is a type of autologous transfusion introduced in the 1970s171–173. It consists in removing at least three or four units of autologous blood, maintaining isovolaemia, immediately before elective surgery174. Acute normovolaemic haemodilution is usually performed after induction of anaesthesia175, just before the surgical incision176. The circulating blood volume is maintained by infusing crystalloids, administering 2–3 mL for every mL of blood removed, or colloids, in a ratio of 1:1 with the volume of blood removed174.

The efficacy of acute normovolaemic haemodilution in reducing the need for allogeneic red blood cell transfusion is, however, doubtful177. Various studies, including prospective, randomised trials, showed that it could reduce recourse to allogeneic transfusion therapy in patients undergoing elective heart surgery, orthopaedic operations (knee replacement), abdominal, vascular, urological, maxillofacial, or liver surgery and in patients undergoing surgery because of burns178–189. However, other studies did not find any substantial benefit or even found an increased need for allogeneic transfusions190–192.