Abstract

The aim was to study the genotoxic effect of high concentration of thyroxine (T4) in vivo in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) of the patients suffering from thyroid disorders. The effect was compared by performing in vitro experiments with addition of increasing concentration of T4 (0.125–1 µM) in whole blood samples from healthy donors. Cytokinesis-blocked micronuclei (CBMN) assay method was used to assess the DNA damage in the PBL. The study included 104 patients which were grouped as control (n = 49), hyperthyroid (n = 31) and hypothyroid (n = 24). A significant increase in micronuclei (MN) frequency was observed in hyperthyroid patients when compared with the hypothyroid and euthyroid group thereby suggesting increased genotoxicity in hyperthyroidism (p < 0.001). A significant increase in MN frequency was observed at T4 concentration of 0.5 µM and above when compared to lower T4 concentrations (0.125 and 0.25 µM) and basal in in vitro experiments (p = 0.000). The results indicate that the T4 in normal concentration does not exhibit the genotoxic effect, as observed in both the in vivo and in vitro experiments. The toxicity of T4 increases at and above 0.5 μM concentration in vitro. Therefore acute T4 overdose should be handled promptly and effectively so as to avoid the possible genotoxic effect of high concentration of T4 in vivo.

Keywords: Genotoxicity, Hyperthyroid, Hypothyroid, Micronuclei, Thyroxine

Introduction

Thyroid hormones are essential for normal development and growth of the body and are involved in regulation of basal metabolic rate (BMR) and oxidative metabolism [1]. Normal concentration of thyroid hormones is crucial for regular functioning of the body and do not show any deleterious effects [2]. However higher levels of these hormones have shown to change the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes which may result in increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [3–6]. It has been observed that higher concentration of thyroid hormones similar to what is found in severely hyperthyroid patients may cause DNA damage in cells [7]. Further in vitro work done to study the effect of thyroxine (T4) has shown positive effect on sister chromatid exchange (SCE) but failed to show similar effect with chromosomal aberration (CA) and micronuclei (MN) assay which would have proved mutagenicity of T4 [2]. Thyroid hormones have shown increase in DNA damage in purified human lymphocytes by using comet assay and damage can be reduced by the antioxidant enzyme catalase, suggesting the genotoxic effects of thyroid hormones could be due to generation of ROS [8].

In hypothyroid state where T4 concentration is less than adequate, no major alterations in cellular oxidative stress is observed by many investigators [5, 9, 10]. Two major pathways have been suggested by which hypothyroid state can offer protection, viz GSH synthesis and mild immunosuppression [11–13].

However, most of the studies done on the genotoxicity of T4 are either carried out in vitro or by using animal models supplemented with T4 [2, 7, 14]. AlFaisal et al. have demonstrated the increase in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) MN frequency in thyroid cancer and toxic goiter patients in comparison to healthy control and hypothyroid patients [15]. We have carried out the study to investigate the DNA damage by using MN assay in PBLs of patients suffering from hypothyroidism as well as hyperthyroidism.

In addition we have tried to simulate the similar situation in vitro as observed in clinically hyperthyroid patients by adding increasing concentrations of T4 in blood of healthy donors and study the MN frequency to see the extent of DNA damage in PBLs with high T4 concentration.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Total 104 subjects were included in the study. Out of these 49 were euthyroid, 24 hypothyroid and 31 were hyperthyroid clinically as well as biochemically. All the study subjects were patients visiting Radiation Medicine Centre for their thyroid check-up or the follow-up. General health characteristics such as age, sex, use of any other drug or disease (other than thyroid) were recorded while collecting the blood samples. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects before collection of the blood sample. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Methods

Serum levels of T4 and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) were obtained from all subjects to confirm the clinical diagnosis of thyroid dysfunction before including them in the study. Serum T4 was estimated by using in-house radioimmunoassay (RIA) technique. Serum TSH was performed by immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) technique using commercially available kits from Board of Radiation and Isotope Technology (BRIT), Vashi, Navi Mumbai, India.

Blood samples of all the patients were processed for estimation of MN frequency by using cytokinesis-blocked micronuclei (CBMN) assay technique. Similarly, MN frequency was also estimated in an in vitro study using blood samples obtained from three female non-smoker healthy donors with mean age 27.3 ± 9.8 years.

Cytokinesis-Blocked Micronuclei Assay

MN assay was performed by using cytokinesis-blocked technique in PBL’s as previously described [16]. Briefly, whole blood cultures were set up by adding 0.5 ml of heparinized blood into 4.5 ml of Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10 % heat inactivated fetal calf serum. Lymphocytes were stimulated by adding 40 µg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA-M, Sigma Aldrich, USA). At 44 h the cytokinesis was blocked by adding 6 μg/ml cytochalasin-B (Sigma Aldrich, USA) in the whole blood culture. Cytochalasin-B generated binucleated cells by inhibiting actin-mediated cytokinesis, thereby preventing cells from completing division. At 72 h of incubation, the cultures were harvested by resuspending the cells with hypotonic solution (0.8 % potassium chloride). The cells were treated with fresh Carnoy’s fixative (methanol:acetic acid, 3:1). After three washes with fixative, the cells were dropped onto ice cold clean microscopic slides, air dried and stained with Giemsa (Sigma Chemical Co. USA). Each slide was screened manually under the microscope for the presence of MN in at least 1000 binucleated (BN) lymphocytes with well preserved cytoplasm.

In Vitro Effect of T4 Concentration on Micronuclei Frequency

Heparinised whole blood samples were obtained by venipuncture from three healthy donors with no medication. Human PBL cultures were set up as per the protocol stated earlier. Increasing concentration of T4 was added in cultivation vials before the initiation of culture incubation to study the effect of increasing concentration of T4 on MN frequency. T4 (Sigma Chemical Co. USA) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and added to the vials so as to obtain final concentration of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 µM. Mitomycin-C (MMC), a known mutagen, obtained from Biochem Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, India was used in the cultures with concentration of 0.1 µg/ml to represent a positive control, while DMSO (0.8 % v/v) served as a negative control. All the samples of in vitro experiment were processed in replicates. The cultures were harvested by using the similar procedure stated earlier and the slides were prepared and scored for the presence of MN in at least 1000 BN cells.

Statistical Analysis

The mean MN frequency was compared for different groups by using ANOVA with correction for multiple comparison. All results are presented with 95 % confidence interval.

Results

Table 1 shows the preliminary data on age, gender and the primary investigation such as serum levels of T4 and TSH in all the 104 study population. The concentration of serum T4 and TSH confirmed the clinical diagnosis of the individual patient which ultimately helped the clinicians to treat them accordingly.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study population (n = 104)

| Euthyroid | Hypothyroid | Hyperthyroid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | 49 | 24 | 31 |

| Gender M/F | 6/43 | 8/16 | 8/23 |

| Age (years) | 39 ± 12.7 | 40.2 ± 16.0 | 41.1 ± 11.8 |

| T4 (µg/dl) | 9.3 ± 1.7 | 5.5 ± 2.7a | 17.2 ± 3.1a |

| TSH (µIU/ml) | 2.6 ± 2.4 | 36.0 ± 31.5a | 0.05 ± 0.11a |

a p < 0.001 versus control

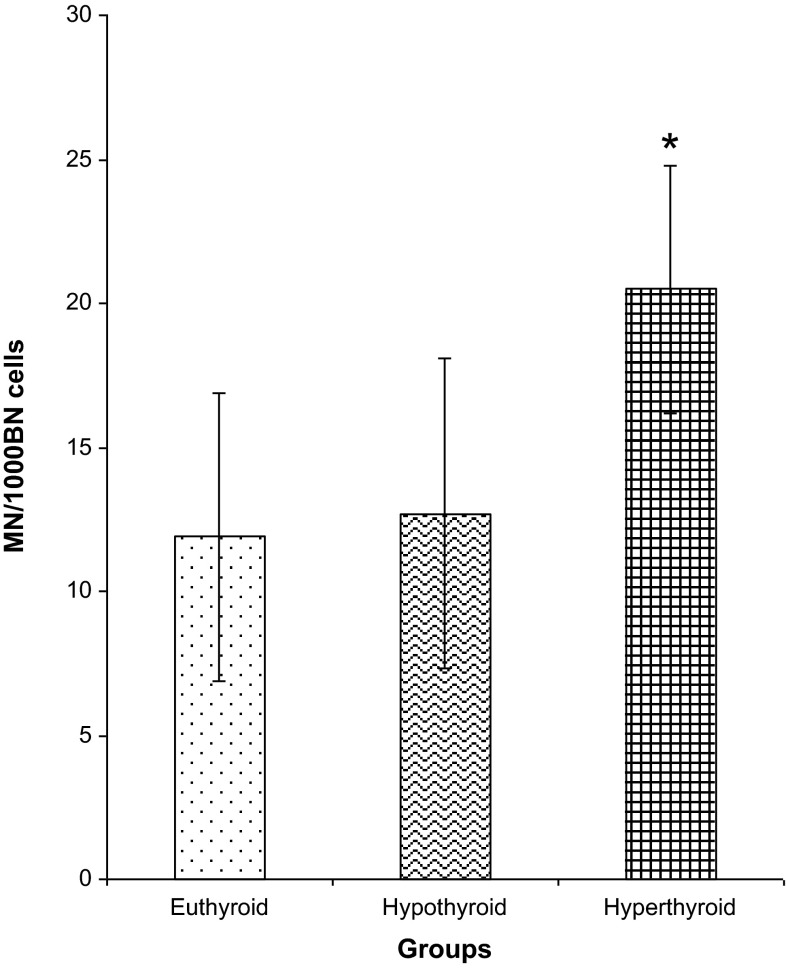

Fig. 1 shows the MN frequency in patients from all the three groups. Mean MN frequency did not differ in hypothyroid patients in comparison to euthyroid (p = 0.333). On the other hand MN frequency was significantly elevated in hyperthyroid patients when compared with hypothyroid (p < 0.001) as well as euthyroid patient population (p < 0.001). MN frequency is known to be influenced according to the age and gender of the individual. However, no such association was observed in the present study when MN frequency was compared with age and gender [Male: mean 17.7 (3.1–27.0) MN/1000 BN cells, n = 22, Female: mean 13.9 (2.0–26.0) MN/1000 BN cells, n = 82, p = 1.000]

Fig. 1.

Micronuclei frequency in peripheral blood lymphocytes of total study population. *p < 0.001 versus euthyroid, hypothyroid

We were further interested in confirming our observations of increased MN frequency in PBLs of hyperthyroid patients by creating an in vitro hyperthyroid condition by adding increasing concentrations of T4 in PBLs of three healthy donors. Gradual increase in MN frequency was observed in all the three donors with T4 concentration ranging from 0.125 to 1.0 µM thereby indicating increase in DNA damage in presence of excess T4 concentration in vitro (Table 2). However increase in MN frequency in BN cells reached statistical significance at 0.5 and 1.0 µM concentration of T4 when compared with their baseline and negative control (Table 2).

Table 2.

In vitro effect of increasing concentration of thyroxine on MN frequency and cytokinesis block proliferation (CBPI) index in peripheral blood lymphocytes of healthy donors (n = 3)

| Groups | Negative control (DMSO) | Baseline | l-thyroxine (µM) | Positive control (MMC) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | ||||

| MN/1000BN cells (mean ± SD) | 13.1 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.5 | 13.1 ± 2.4 | 18.2 ± 3.1 | 29.7 ± 3.4#,* | 36.5 ± 2.5##,** | 112.5 ± 7.7##,** |

| CBPI (mean ± SD) | 1.4 ± 0.14 | 1.6 ± 0.04 | 1.5 ± 0.05♣ | 1.4 ± 0.05♣♣ | 1.3 ± 0.04♦ | 1.2 ± 0.04♦♦ | 1.4 ± 0.09 |

p# = 0.002, ## < 0.001 versus negative control

p* = 0.001, ** < 0.001 versus baseline

p ♦ = 0.002, p ♦♦ < 0.001 versus baseline

p ♣ = 0.001, p ♣♣ = 0.004 versus 1 μM

Additionally we have also observed the cytotoxic and cell-cycle delay effect of T4 by using the same slides from all the three donors. Cytokinesis-block proliferation index (CBPI) showed decreasing trend as the T4 concentration increases (Table 2). The T4 concentration of 0.5 and 1.0 µM showed significant decrease in CBPI in comparison to baseline values in all the three donors (Table 2).

Discussion

Thyroid hormones are known to alter the basal metabolic rate of the body and in turn also control the ROS generation in the cell [3–6].Relationship between oxidative stress, excessive ROS generation and hypo as well as hyperthyroidism has been explored in the past [5, 6, 9, 10, 17–22]. Oxidative stress due to excessive ROS generation is known to be one of the underlying cause of the cellular DNA damage, however very few studies are available regarding the relationship between the presence of DNA damage and hypo or hyperthyroid condition [23]. In the present study we have tried to see the effect of hypo and hyperthyroid state on the extent of DNA damage by measuring the MN frequency in PBL, in vivo as well as in vitro.

In the present study hypothyroid group did not demonstrate any change in the MN frequency when compared with the euthyroid controls thereby indicating absence of genotoxic effect in hypothyroid condition. AlFaisal et al., in their study of Iraqi population have reported no change in MN frequency in hypothyroid patients when compared with euthyroid group suggesting absence of significant DNA damage in PBLs under hypothyroid condition [15]. This is in agreement with our observations. Hypothyroidism is generally associated with the lowering of the metabolic rate which may lower the rate of ROS production [5, 9, 10]. This may result in lack of significant DNA damage in PBLs of hypothyroid patients.

We have explored the effect of hyperthyroid condition in patient population on genetic stability and observed significant increase in MN frequency in PBL indicating notable DNA damage. Equivocal and few reports about genotoxicity and hyperthyroid conditions in patient population are available in literature [15, 23, 24]. Thakkar et al. in their study in mixed patient population of thyroid disorders and diabetes mellitus did not observe any effect of hyperthyroidism on DNA damage while AlFaisal et al. have observed increase in PBL MN index in hyperthyroid conditions [15, 24]. However the effect observed by Thakkar et al. was not solely the result of thyroid disorders as it was also accompanied by diabetes mellitus [24].

In vitro experiments set up in the present study to substantiate the in vivo observations about genotoxic effect of hyperthyroidism demonstrated increased MN index in PBLs in vitro at and above 0.5 μM T4 concentration indicating possibility of considerable DNA damage at such high T4 concentration. Increased frequency of sister chromatid exchange and lack of increase in PBL MN frequency in presence of higher T4 concentration in vitro has been reported by Djelic et al. [14]. However excessive thyroid hormones have been shown to demonstrate increased DNA damage in human lymphocytes and sperm by comet assay and the reduction of the same in presence of enzyme catalase and flavonoids indicating role of ROS in inducing DNA damage [7, 8]. Mihara et al. in their in vitro experiments with PBLs of healthy volunteers and Graves disease patients have also noted increased DNA damage as shown by excessive DNA laddering and subsequent cell apoptosis in vitro when these cells were co cultured with higher T4 concentrations [23]. They have reported reduction in mitochondrial transmembrane potential and production of ROS both of which are intimately associated with apoptotic cell death [23]. Similarly increase in PBL apoptosis was observed in Graves disease patients. They have observed reduction in expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein which was clearly reduced in lymphocytes co cultured with excess of thyroid hormone. Interestingly in the present study significant reduction in CBPI index was noted in PBLs at higher T4 concentrations in vitro experiments which could be due to increased apoptosis at high T4 concentration.

In summary we have observed increase in MN index in PBL’s of hyperthyroid patients having high levels of thyroid hormones in circulation. Similarly increase in MN frequency was observed in vitro at higher T4 concentrations of 0.5 and 1 µM in comparison to their baseline levels (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001 resp.). However the low concentration of 0.125 and 0.25 µM did not cause significant changes in MN frequency thereby showing no cytotoxic effect of T4 at normal concentration.

In conclusion, the regular T4 replacement therapy given to patients to maintain the euthyroid status need not cause any genotoxic effects in patients. However, acute T4 overdose should be handled promptly and effectively so as to avoid the possible genotoxic effect of high concentrations of T4 in vivo.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Yogita S. Raut, Phone: +91-2224149428, Email: yogita.raut@gmail.com

Uma S. Bhartiya, Email: bhartiyau@yahoo.com

Purushottam Kand, Email: kandpg@yahoo.co.in.

Rohini W. Hawaldar, Email: rwhawaldar@gmail.com

Ramesh V. Asopa, Email: rasopa@yahoo.com

Lebana J. Joseph, Email: lebanajoseph@yahoo.in

MGR Rajan, Email: mgr_rajan@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Halliwell B. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1147–1150. doi: 10.1042/BST0351147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Djelic N, Ivana N, Stanimirovic Z, Jovanovic S. Evaluation of the genotoxic effects of thyroxine using in vivo cytogenetic test on swiss albino mice. Acta Veterinaria (Beograd) 2007;57:487–495. doi: 10.2298/AVB0706487D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mano T, Sinohara R, Sawai Y. Effects of thyroid hormone on coenzyme Q and other free radical scavenger in rat heart muscle. J Endocrinol. 1995;145:131–136. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1450131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerrero A, Pamplona R, Portero-Otin M, Barja G, Lopez-Torres M. Effect of thyroid status on lipid composition and peroxidation in mouse liver. Free Rad Biol Med. 1999;256:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coria MJ, Pastran AI, Gimenez MS. Serum oxidative stress parameters of women with hypothyroidism. Acta Biomed. 2009;80:135–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrulea MS, Duncea I, Muresan A. Thyroid hormones in excess induce oxidative stress in rats. Acta Endocrinol (Buc) 2009;5:155–164. doi: 10.4183/aeb.2009.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobrzynska MM, Baumgartner A, Anderson D. Antioxidants modulate thyroid hormone and nonadrenaline-induced DNA damage in human sperm. Mutagenesis. 2004;13:325–330. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djelic N, Anderson D. The effect of the antioxidant catalase on oestrogen, triiodothyronine and noradrenaline in the Comet assay. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 2003;23:69–81. doi: 10.1002/tcm.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE. Role of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress in the association between thyroid diseases and breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2008;68:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenorio-Velasquez VM, Barrera D, Franco M, Tapia E, Hernandez-Pando R, Medina-Campos ON, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Hypothyroidsim attenuates protein tyrosine nitration, oxidative stress and renal damage induced by ischemia and reperfusion: effect unrelated to antioxidant enzymes activities. BMC Nephrol. 2005;7:6–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cano-Europa BVV, Margarita FC, Rocio OB. The relationship between thyroid states, oxidative stress and cellular damage. In: Lushchak VI, Gopodaryov DV, editors. Oxidative stress and diseases. Rijeka: InTech; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenfeld PS, Myers JW, Myer L, LaRocque JC. Suppression of cell-mediated immunity in hypothyroidism. South Med J. 1995;88:347–349. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199503000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amadi K, Sabo AM, Ogunkeye OO, Oluwole FS. Thyroid hormone: a “prime suspect” in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV/AIDS) patients? Physiol Soc Niger. 2008;23:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djelic N, Biljana SP, Vladan B, Dijana D. Sister chromatid exchange and micronuclei in human peripheral blood lymphocytes treated with thyroxine in-vitro. Mutat Res. 2006;604:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AlFaisal AHM, Al-Ramahi ITK, Hassan IARA. Micronucleus frequency among Iraqi thyroid disorder patients. Comp Clin Pathol. 2014;23:683–688. doi: 10.1007/s00580-012-1671-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph LJ, Patwardhan UN, Samuel AM. Frequency of micronuclei in peripheral blood lymphocytes from subjects occupationally exposed to low levels of ionizing radiation. Mutat Res. 2004;564:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bianchi G, Solaroli E, Zaccheroni V, Grossi G, Bargossi AM, Melchionda N, Marchesini G. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolites in patients with hyperthyroidism: effect of treatment. Horm Metab Res. 1999;31:620–624. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komosinska-Vassev K, Olczyk K, Kucharz EJ, Marcisz C, Winsz-Szczotka K, Kotulska A. Free radical activity and antioxidant defense mechanisms in patients with hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease during therapy. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;300:107–117. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(00)00306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasupathi P, Latha R. Free radical activity and antioxidant defense mechanisms in patients with hypothyroidism. Thyroid Sci. 2008;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marjani A, Mansourian AR, Ghaemi EO, Ahmadi A, Khori V. Lipid peroxidation in the serum of hypothyroid patients (in Gorgan-South East of Caspian Sea) Asian J Cell Biol. 2008;3:47–50. doi: 10.3923/ajcb.2008.47.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babu K, Jayaraaj IA, Prabhakar J. Effect of abnormal thyroid hormone changes in lipid peroxidation and antioxidant imbalance in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011;2:1122–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tapai G, Santibanez C, Farias J, Fuenzalida G, Varela P, Videla LA, Fernandez V. Kupffer-cell activity is essential for thyroid hormone rat liver preconditioning. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;323:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mihara S, Suzuki N, Wakisakas S, Suzuki S, Sekita N, Yamamoto S, Saito N, Hoshino T, Sakane T. Effects of thyroid hormones on apoptotic cell death of human lymphocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;4:1378–1385. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.4.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thakkar NV, Jain SM. A comparative study of DNA damage in patients suffering from Diabetes and thyroid dysfunction and complications. Clin Pharmacol Adv Appl. 2010;2:199–205. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S11366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]