Abstract

Background

There is limited literature in the management of chronic urticaria in children. Treatment algorithms are generally extrapolated from adult studies.

Objective

Utility of a weight and age-based algorithm for antihistamines in management of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) in childhood. To document associated factors that predict for step of control of CSU and time taken to attain control of symptoms in children.

Methods

A workgroup comprising of allergists, nurses, and pharmacists convened to develop a stepwise treatment algorithm in management of children with CSU. Sequential patients presenting to the paediatric allergy service with CSU were included in this observational, prospective study.

Results

Ninety-eight patients were recruited from September 2012 to September 2013. Majority were male, Chinese with median age 4 years 7 months. A third of patients with CSU had a family history of acute urticaria. Ten point two percent had previously resolved CSU, 25.5% had associated angioedema, and 53.1% had a history of atopy. A total of 96.9% of patients achieved control of symptoms, of which 91.8% achieved control with cetirizine. Fifty percent of all the patients were controlled on step 2 or higher. Forty-seven point eight percent of those on step 2 or higher were between 2 to 6 years of age compared to 32.6% and 19.6% who were 6 years and older and lesser than 2 years of age respectively. Eighty percent of those with previously resolved CSU required an increase to step 2 and above to achieve chronic urticaria control.

Conclusion

We propose a weight- and age-based titration algorithm for different antihistamines for CSU in children using a stepwise approach to achieve control. This algorithm may improve the management and safety profile for paediatric CSU patients and allow for review in a more systematic manner for physicians dealing with CSU in children.

Keywords: Chronic Urticaria, Child, Algorithms, Histamine Antagonists

INTRODUCTION

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is characterized by the recurrent occurrence of short-lived cutaneous wheals accompanied by redness and itching, with or without angioedema, for more than 6 weeks [1]. There appears to be different prevalence of CSU reported in children, around 0.1–0.3% in United Kingdom [2] and up to 13% of children in Thailand [3]. As opposed to adult studies whereby there are reports of 40% of adults having accompanying episodes of angioedema [4], Volonakis et al. observed that in children with CSU [5], only 15% of children had concomitant angioedema and urticaria [6]. Often, no identifiable cause is found for CSU in up to 70% to 90% of adults and children respectively [7]. In adults with CSU, the prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease has been estimated to be 14–33%. While it is much lower in children, one paediatric study reported a rate of 8 of 187 patients (4.3%), all of whom were female and aged 7–17 years [8]. It is plausible that thyroid autoantibodies and hypothyroidism may appear several years after the onset of CU, although this has not been studied prospectively. In a study of children at a tertiary referral centre, there was a longer and more severe course of CSU with only 11.6% of the patients achieving remission of their symptoms after 1 year; after 5 years, the percentage improved to only 38.4% [2]. Second-generation H1-antihistamines remain the treatment option of choice. A recent Cochrane review which included randomized, placebo controlled trials, demonstrated that secondgeneration H1-antihistamines reduce the major symptoms of CSU, such as pruritus, wheal formation and disruption of sleep and daily activities. Cetirizine appears to be most effective for complete remission of urticaria for the short term and intermediate term as compared to the other second-generation antihistamines [9]. Antihistamines may have to be taken over extended periods of time to control the disease. High doses of H1-antihistamines may be required to obtain sufficient symptom control in urticaria. Adverse effects of H1-antihistamines vary between individuals, and some may tolerate one antihistamine better than another [10].

Presently, published guidelines suggest a standardized approach to the management of refractory CSU extrapolated from adult experience. The step-up dose of second-generation antihistamines would be a 2- to 4-time increase for adults without consideration of the weight of the patients [11,12]. These guidelines are difficult to implement as the weight of children varies considerably. We propose that there is a need for an easy to use and therapeutically appropriate protocol and dosing table tailored for the pediatric population instead, to easily find the optimal dosage regimes within a shorter time, to achieve control of their CSU with minimal side effects from treatment. A workgroup comprising of allergists, nurses, and pharmacists convened to devise a step wise weight-based antihistamine titration table to use to achieve CSU control effectively and to allow a safer prescriber practice. The study will serve as a useful guide for clinicians to assess the dose that most pediatric patients are controlled on and to titrate to the lowest dose needed to maintain CSU control bearing in mind that some patients may require up to several weeks to months and even years for CSU to achieve remission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The study was approved by the Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board, KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH), Singapore. The prospective study was conducted in the Paediatric Allergy Clinic, KKH, Singapore, from September 2012 to December 2013. Children aged between 0.5 to 16 years with urticaria present daily or almost daily for duration of at least 6 weeks were included in the study.

Treatment

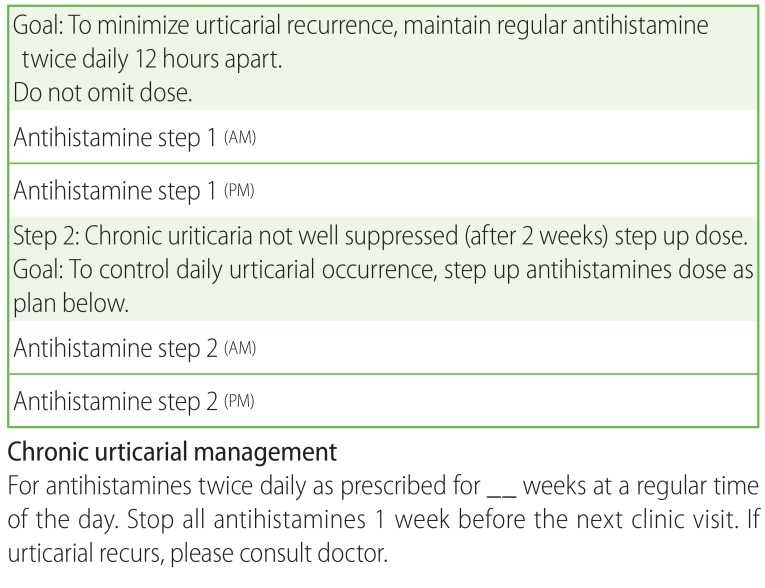

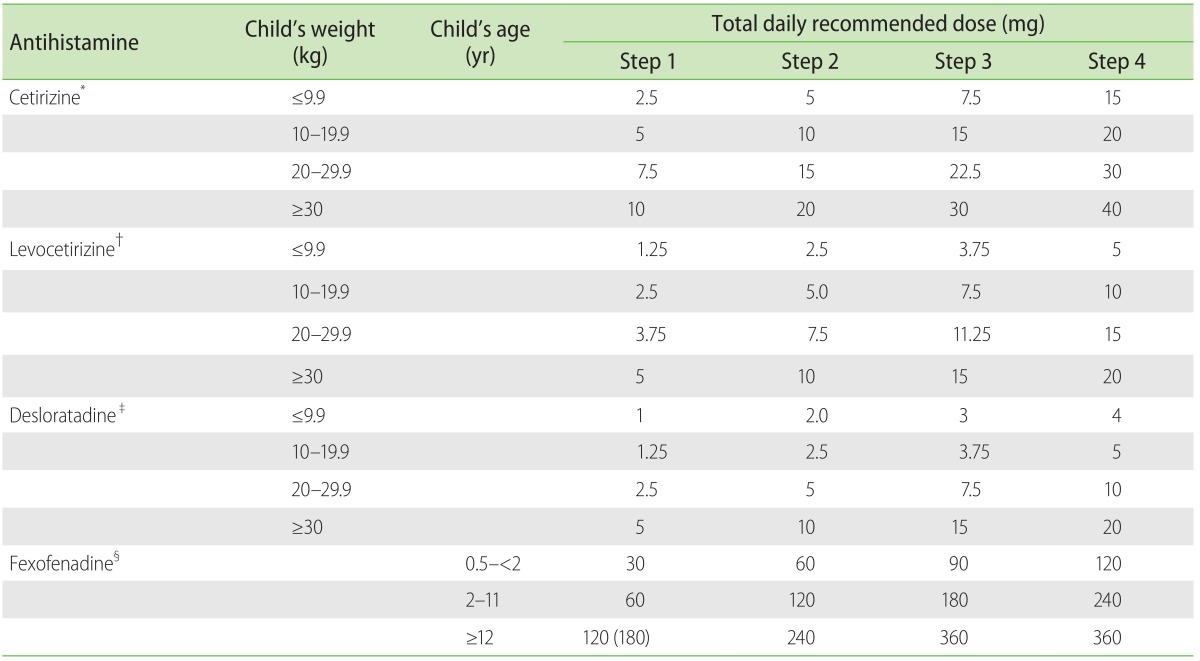

The workgroup devised both an action plan for CSU patients (Fig. 1) and a paediatric CSU antihistamine treatment drug dosing table (Table 1). Literature review had been performed, alongside referenced guidelines from the British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology (BSACI) Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Urticaria and Angioedema [12], and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, European Dermatology Forum & World Allergy Organization (EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO) Guideline for the Management of Urticaria [11].

Fig. 1. Action plan for chronic spontaneous uriticaria patients.

Table 1. Algorithm for weight based antihistamine dosing titration in children.

*Tablet, 10 mg; oral soln, 1 mg/mL; 0.25 mg/kg once or twice daily. †Tablet, 5 mg; oral soln, 0.5 mg/mL; 0.125 mg/kg once daily. ‡Tablet, 5 mg; syrup, 0.5 mg/mL; 0.05 mg/kg twice daily §Tablet, 120 mg, 180 mg; syrup, 6 mg/mL; 6 months–2 years, 15 mg twice daily; 2–11 years, 30 mg twice daily; ≥12 years, 60 mg twice daily or 180 mg once daily.

Antihistamines used for treatment were second-generation H1-antihistamines (cetirizine, desloratadine, levocetirizine, and fexofenadine) with good efficacy reported in management of CSU in both adults and children, although different antihistamines differ in their efficacy in suppression of CSU. Cetirizine was initiated in the majority of patients unless they were commenced on a different antihistamine already by their physician prior to the consult. The reference antihistamine drug dosing table was devised to ensure safety in dosing especially when the weight of children at the same age can vary considerably. Each antihistamine was dosed according to the weight of the patient into step 1 (usual recommended daily dose), step 2 (twice the recommended daily), step 3 (3 times the recommended daily dose), and step 4 (4 times the recommended daily dose).

Data collection

All data was entered into data collection forms during each consult. Demographics (age, sex, race) and clinical (comorbidities, any atopy or drug allergy, any food allergy, symptoms preceding onset of CSU, presence of associated angioedema, family history of urticaria, angioedema or autoimmune conditions, step of CSU control, and time to control CSU) characteristics were collected.

Assessment of disease severity

In the assessment of disease severity, the scoring system proposed by Mlynek et al. was used with a slight modification [13,14]. Urticaria Activity Score (UAS) was taken on initial consultation at the allergy clinic taking into account 4 components: number of wheals, severity of pruritus, duration of hives, and size of wheals. The summed UAS ranges from 0 to 12. Namely, 0 for no wheals, 1 for <10 wheals/day, 2 for 10–50 wheals/day, 3 for >50 wheals/day or large confluent areas of wheals, 0 for no pruritus, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, or 3 for intense, 0 for no hives, 1 if hives lasted for <1 hour/day, 2 if hives lasted for 1–3 hours/day, 3 if hives lasted for >3 hours/day and for size of hives, score was allotted 0 if there were no hives, 1 if size of hives <1 cm, 2 if size of hives was between 1–3 cm, 3 if size >3 cm.

Criteria for control

"Urticaria control" is defined in this study as the absence of urticarial lesions while on the same daily dose of antihistamine over subsequent outpatient visits usually spaced 6 to 12 weeks apart.

One outcome measure was defined as whether CSU was controlled in step 1 vs. step 2 or higher and treated as binary data and another outcome defined as time to control CSU and treated as time to event data.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics outcome were summarized as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous data and frequency with its corresponding proportion for categorical variables. Time to control outcome was summarized as median (SD). Association between binary outcome and other categorical variables were evaluated using Fischer exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify risk factors associated in controlling CSU at step 1 vs. step 2 or higher steps. Results from the logistic regression were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to identify associated prognostic risk factors with respect to time to control CSU. Results from univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were expressed as hazard ratio (HR) and its corresponding 95% CI.

Significance level was set at 5% and all tests were two sided. SAS ver. 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the analyses. For logistic regression PROC Logistic and for survival analysis PROC PHREG procedures were used.

RESULTS

Patient demographics and characteristics

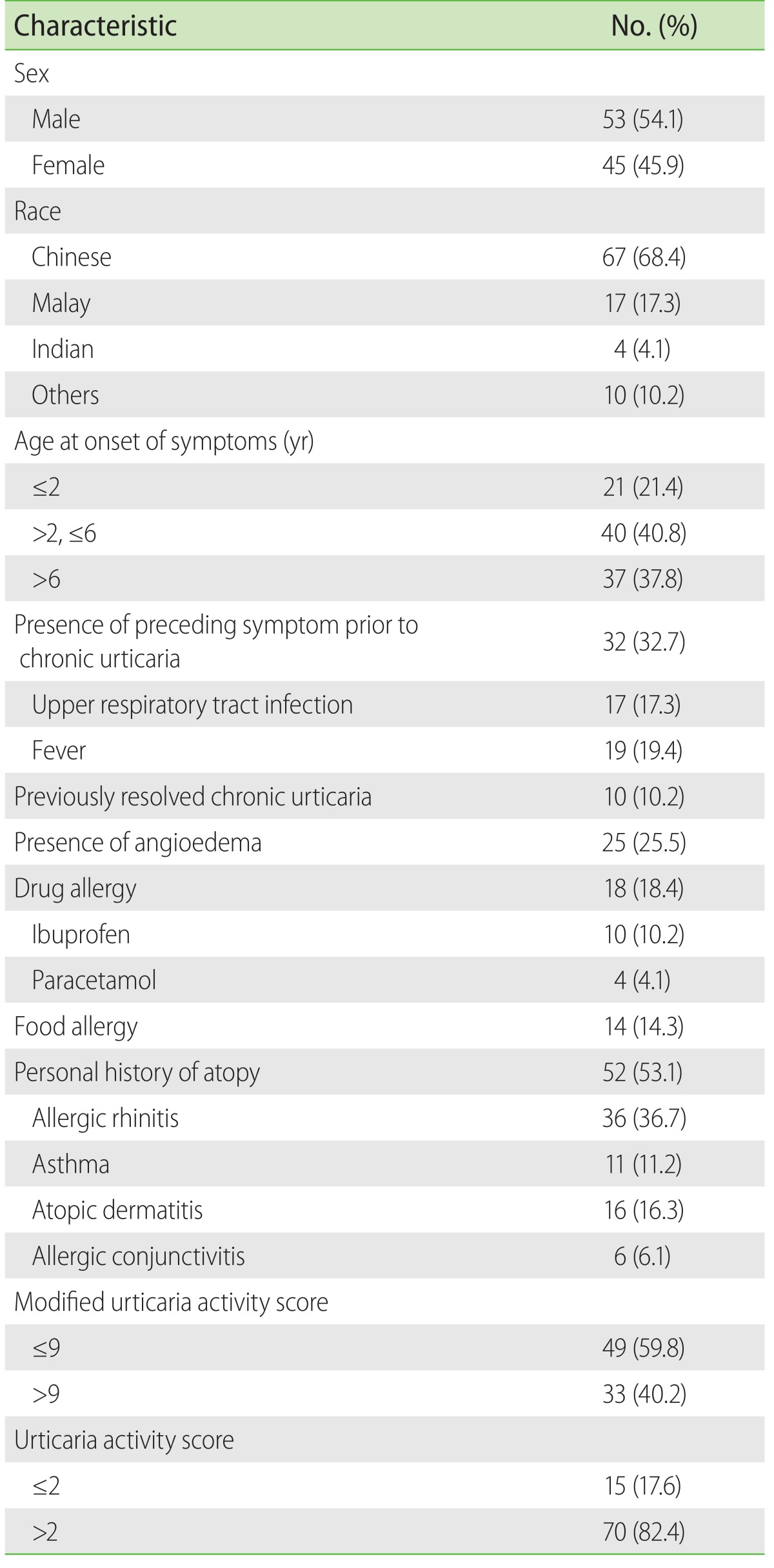

A total of 98 patients with median age of 4.6 years (range, 0.5–15.6 years) at initial visit, 68.4% Chinese and 54.1% males were seen. Forty-one percent of the patients were between 2 to 6 years old, 10.2% had previously resolved CSU, 53.1% had atopy, which included allergic rhinitis (36.7%), asthma (11.2%), or atopic dermatitis (16.3%). The two most common drug allergies were to ibuprofen (10.2%) and paracetamol (4.1%). Of 25.5% of the patients with angioedema, 72.0% presented with periorbital oedema. Amongst the older children aged 6 years and above, 37.8% were likely to have angioedema at initial presentation. Children aged 6 years and above were more likely (56.0%) to present with accompanying angioedema compare to younger age groups. Disease severity was assessed using the modified UAS which is a median of 9. Forty percent of the patients obtained a UAS of 9 or greater (Table 2). A total of 28 patients (28.4%) had a family history of acute urticaria (AU). AU was more common in mothers compared to fathers (50.0% vs. 35.7%).

Table 2. Demographics characteristics of children presenting with chronic spontaneous urticaria (n = 98).

Twelve patients (12.2%) had a family history of CSU, 5 (5.0%) had a family history of angioedema, and 16 of the patients (16.3%) had a family history of autoimmune diseases. The common autoimmune diseases include thyroid dysfunction (12.2%), rheumatoid arthritis, and gout.

Majority of our CSU pediatric patients were on cetirizine as it is deemed cost effective, and clinically effective in the pediatric population. Other antihistamines used were desloratadine, fexofenadine, and levocetirizine. Of the 98 children evaluated, 95 attained control. Ninety-one point eight percent of these were controlled with cetirizine.

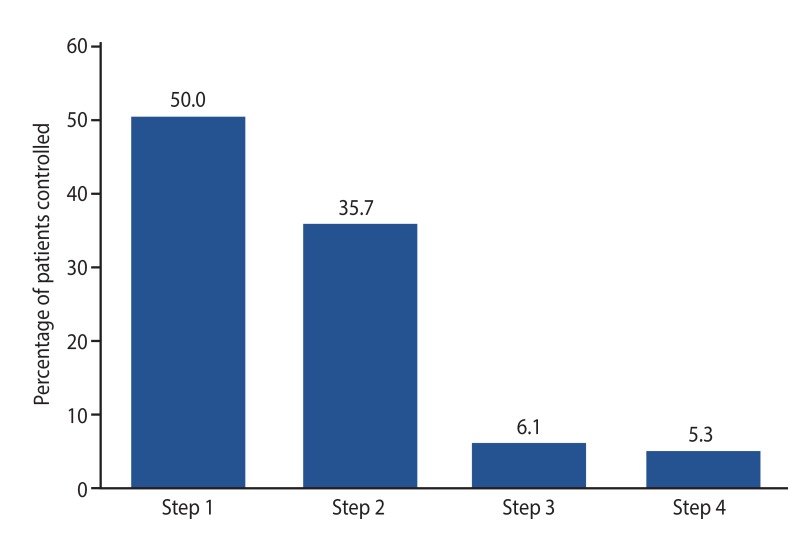

Fifty percent were controlled at step 1 while 35.7%, 6.1%, and 5.3% were controlled at step 2, step 3, and step 4, respectively. Median duration (range) of time in weeks to control CSU at step 1, step 2, step 3, and step 4 were 2 (2–18), 8 (2–22), 9.5 (2–14), and 14.5 weeks (2–42 weeks), respectively. Two children remained noncompliant to treatment regimen and experienced recurrent hives daily and one child was lost to follow up.

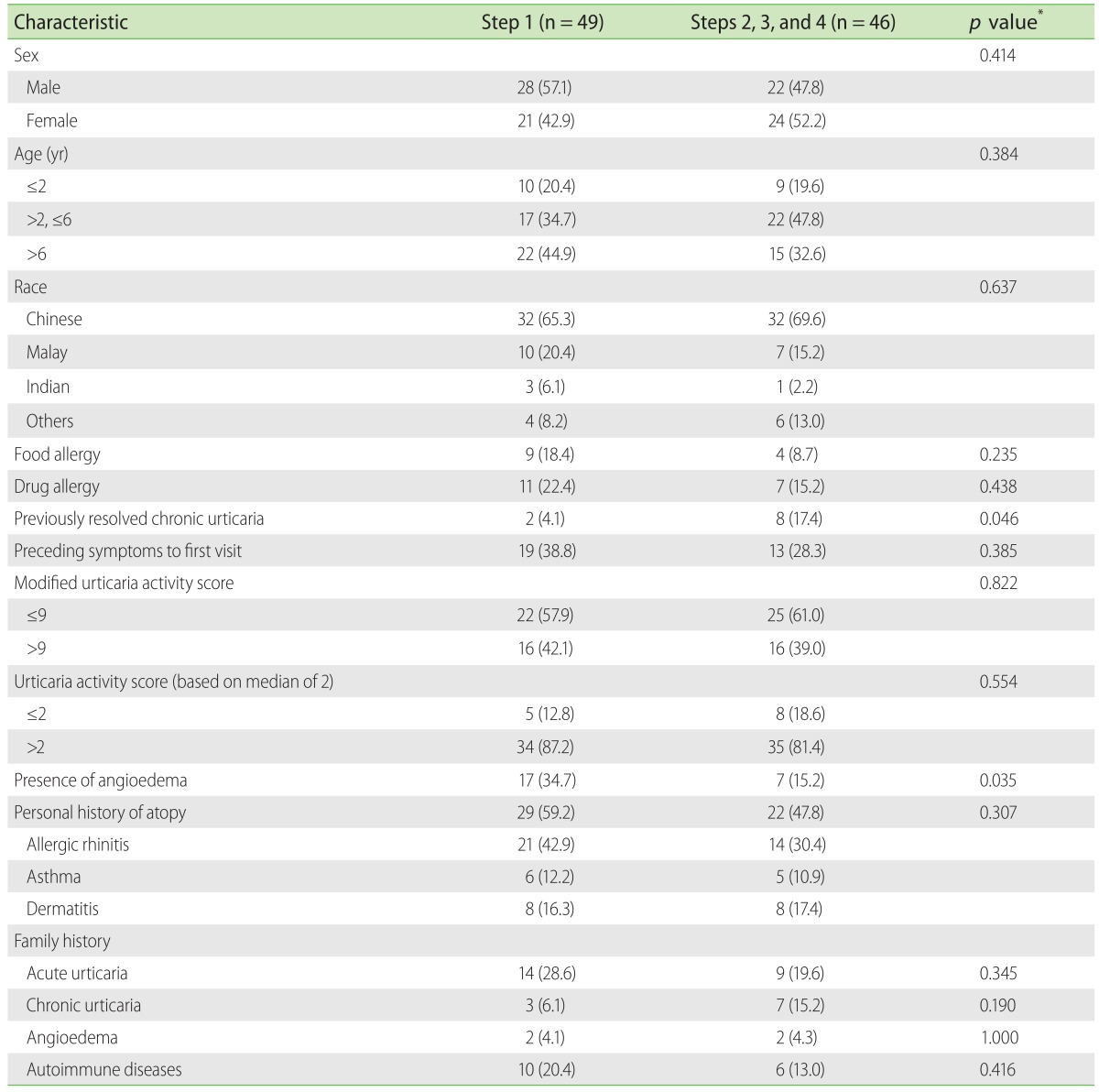

It was observed in our study that 47.8% of patients on step 2 antihistamine dosing or higher were between 2 to 6 years of age compared to 32.6% who were 6 years and older and 19.6% who were lesser than 2 years of age respectively. In our study, when the presence of atopy was analyzed against step of control, no statistical significance was found. No significant difference was observed with modified UAS or UAS score and steps needed to control CSU. Children with previously resolved CU needed step 2 or higher to control CSU (p = 0.046). (Table 3)

Table 3. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients had controlled chronic spontaneous urticaria in step 1 vs. step 2 or higher.

Values are presented as number (%).

*Fisher exact test.

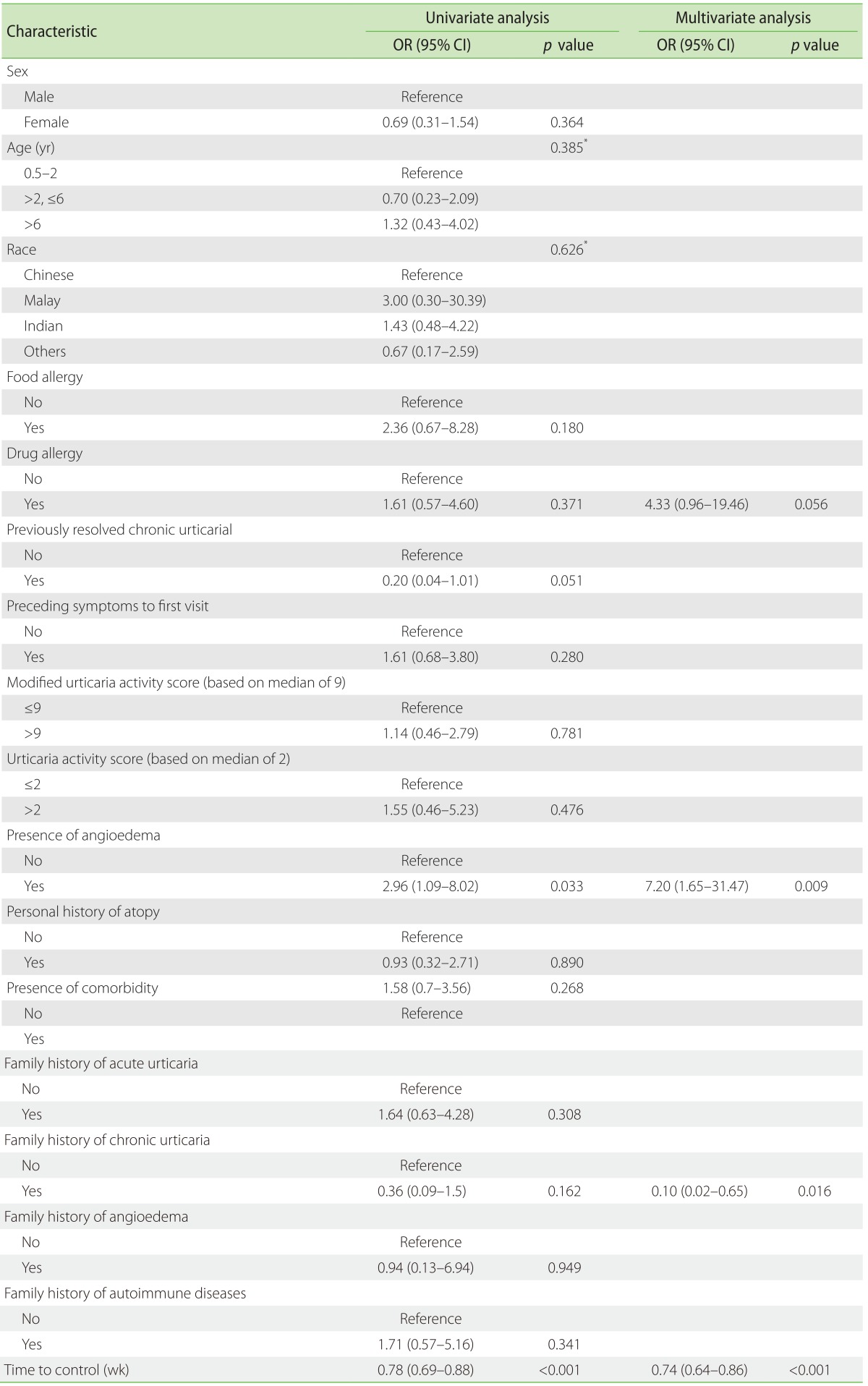

Univariate logistic regression showed that presence of angioedema (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.1–8.0) and time to control (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.69–0.88) were risk factors which influenced the step required to control CSU. Multivariate logistic regression showed that presence of angioedema (OR, 7.2; 95% CI, 1.7–31.5), family history of CSU (OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02–0.65), time to control (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.64–0.86), and any drug allergy (OR, 4.33; 95% CI, 0.96–19.46) from CSU were associated risk factors that influenced the step required to control CSU (Table 4).

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to predict associated risk factors in controlling chronic spontaneous urticaria in step 1 vs. steps 2–4 (modelled for success = step 1).

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AIC, Akaike Information Criterion.

*Type III p value. AIC = 100.346 (multivariate model).

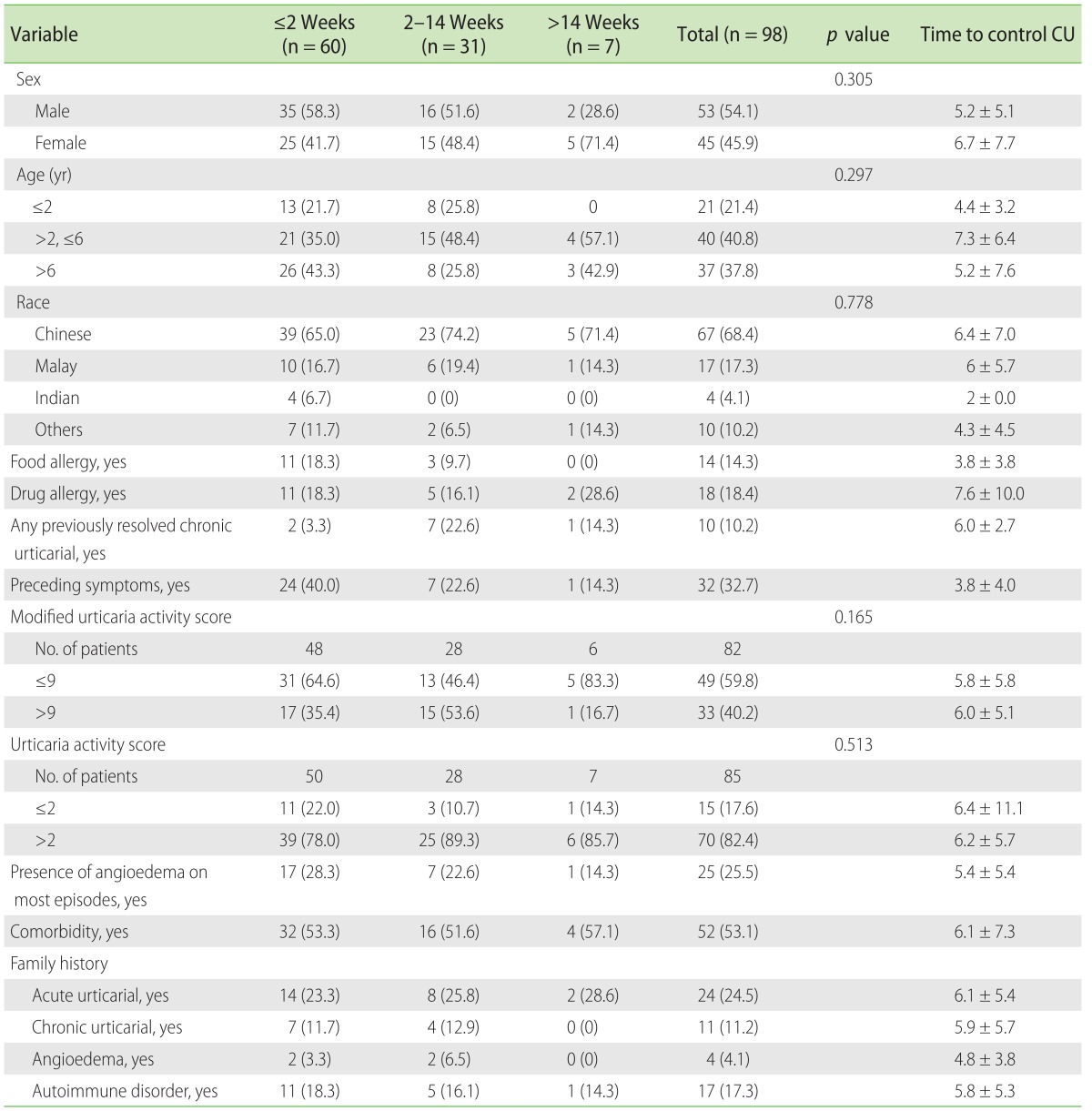

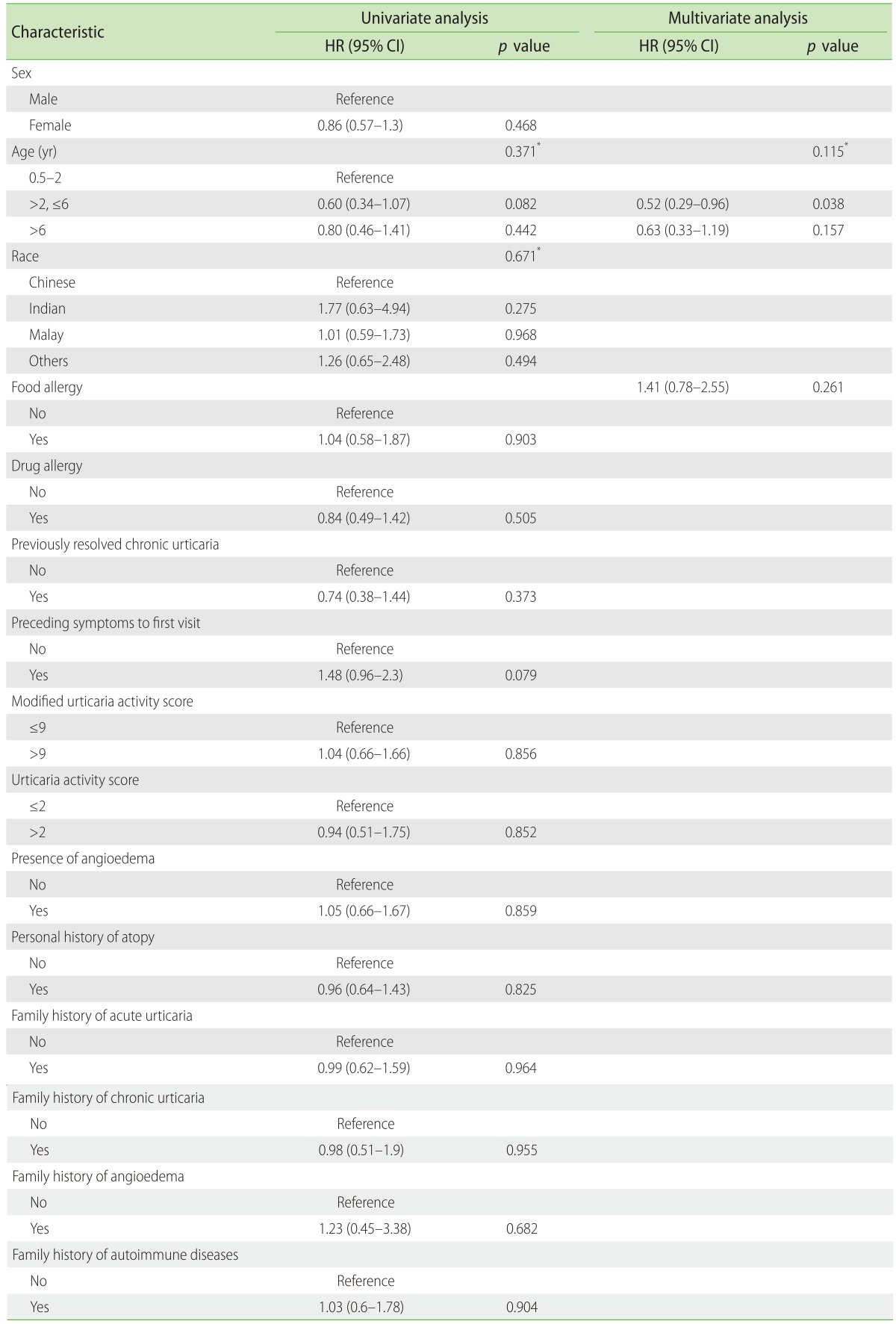

The youngest group attained faster CSU control as compared to older age group children. Sixty percent of children less than 2 years of age attained control within 2 weeks and 90% within 12 weeks. Children with a family history of CSU and angioedema tended to take a longer time (mostly >2 weeks) as compared to patients without family history to attain control of CSU symptoms (Table 5). In univariate and multivariate Cox regression, none of the factors, including age, sex, previously diagnosed with CSU, presence of angioedema, drug allergy, food allergy were found to be associated with time to control CSU (Table 6).

Table 5. Number of patients who achieved symptom control at <2 weeks, 2 to 14 weeks, and >14 weeks, respectively (n = 98).

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

CU, chronic urticaria.

Table 6. Univariate and multivariate analysis demonstrating the relationship of time to control of chronic spontaneous urticaria symptoms (weeks) with demographic data using the Log-rank test and Cox regression analysis.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; AIC, Akaike Information Criterion.

*Type III p value. AIC = 100.346 (multivariate model).

DISCUSSION

The management of CSU in children is often extrapolated from adult studies with paucity in data in management of children with CSU and their response to therapy. Current guidelines recommend an algorithmic stepwise increment of second-generation antihistamines up to 4 times the standard daily dose. However, unlike adults where the weight is less of an issue with titration of antihistamine dosing, in children, we often have to work with a range of weight depending on the age of child who presents to us. CSU can present in children as young as less than 6 months old, with parents who are often unwilling to adhere to a step up dosing as they are worried about the safety of the increased dose of medications and often accept uncontrolled hives for several months before review [15]. Sussman et al. [16] have observed that uncontrolled hives for months to years prior to being seen has an effect on time to disease control.

We carried out a prospective study to improve the management of CSU in paediatric patients in our local institution with the introduction of a weight adjusted standardized dose titration table (Table 1) and a written CSU action plan (Fig. 1) for all patients. In our study, by giving parents a step wise written plan, we hope to increase adherence and ultimately, an improvement in the control of CSU symptoms.

The demographic data suggests that in our region, the pediatric patients with CSU are mainly Chinese males. This is in contrast to studies where CSU is shown to be predominant in females in adults [17]. The median age of patients in our study at initial visit is 4.6 years which is lower when compared to most studies on children with CSU, which report a median age of 6–11 years [14,17]. However the age range varied widely, ranging from the first few years of life to adolescence. In our study, we found out that CSU occurs even in children <2 years old and is most common in children aged 2 to 6 years. (21.4% vs. 40.8%). This might support previous postulations that the development of CSU could possibly involve the action of environmental factors on a genetically predisposed host. With increasing age and the gradual development of the immune system, environment and physical triggers may play a greater role [16].

Fifty-three point one percent of the patients in our study presented with pre-existing atopic conditions. As seen in other studies, presence of atopy has become more prevalent in patients with CSU [18]. The frequencies of allergic rhinitis, asthma, and atopic dermatitis in our study were 36.7%, 11.2%, and 16.3%, respectively. These frequencies did not differ widely from that of the general Singaporean population [19]. Patients with pre-existing atopy were not found to require a higher than the usual recommended dose of antihistamines compared to those without pre-existing atopy (Table 3). The percentage of angioedema in our study is 25.5% which falls in the range of 15% to 60% in some studies [20,21]. The common perception of food allergy documented in our study by the parents were egg (6.1%), cow's milk (4.1%), peanut (4.1%), and shellfish (2.0%). However, the prevalence of egg and cow's milk allergy in Singaporean children who are aged 3 and younger were reported to be 1.8% and 0.5% respectively. For children aged 4 to 6 years old, peanut allergy is low at 0.64% while shellfish allergy is high at 1.19% [22]. Patients with CSU often present with concerns of perceived food allergies and in majority of cases, food allergy is not the cause and this can be excluded by clinical history alone. Physician diagnosed food allergy was almost none of the patients followed up in this cohort.

Presence of antipyretics such as ibuprofen and paracetamol allergy in children in our local population is prevalent [23,24]. In some cases, intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is reported to precede by years the onset of chronic urticarial [18].

Twenty-eight patients reported a family history of AU, of whom 14 (50.0%) had a family history of mothers who have AU. Four (4.1%) had a family history of angioedema. Ten (10.2%) had a family history of CSU. A family history of autoimmune diseases was seen in 16 of the CSU patients (16.3%) with 5 of them being first degree family members and 11 being extended family members. The autoimmune diseases included thyroid disease and rheumatoid arthritis. This history is pertinent in a patient presenting with CSU as additional investigations such as autoimmune markers have to be considered in the workup to rule out autoimmunity.

Step of control

According to the BSACI Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Urticaria and Angioedema and the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the Management of Urticaria [11,12]. Nonsedative second-generation H1-antihistamines that have good safety profile are recommended as first-line therapy for patients with CSU. The antihistamines should be taken on a regular basis and prescribed according to age, weight, health status, and individual response. Updosing of the nonsedating antihistamine up to 4 times the standard dose is recommended if clinical response is not attained after 2 weeks [11,12]. Smaller increments of nonsedative antihistamines can be considered in Asians due to smaller body mass index [25].

There are limited studies to date that show the number of pediatric patients who are controlled on the different steps of antihistamines for CSU in Asians. In our study, it can be seen that most patients are controlled at step 1 (50.0%) and step 2 (35.7%), based on our antihistamine weight based titration table. Only 11.4% of patients required the dose of cetirizine to be increased to step 3 or 4 (Fig. 2). Knowing that a large majority of patients can be controlled on lower doses of antihistamines is useful to clinicians. They can better reassure parents that in most cases, the doses need not be increased to more than 3 times its standard dosing. Better reassurance will lead to compliance and thus better management of CSU. Also, the aim of treatment is to use the lowest effective dose to attain control so that there will be minimal side effects. To date, we have not had to use cyclosporine or omalizumab for any of our patients.

Fig. 2. Patients who achieved chronic spontaneous urticaria control on stepwise titration of weight based antihistamines according to Table 1. The vertical bars show the percentage of patients controlled on steps 1, 2, 3, and 4 of antihistamines respectively.

Multivariate regression showed that the presence of a family history of CSU, angioedema and drug allergy may predispose patients to require higher step dose of 2, 3, and 4 of antihistamine to achieve control.

Time to control

In our study, time to control refers to the time that a patient takes to be symptom free on the dose of antihistamine by the subsequent clinic visit. Resolution of symptoms may require a longer time. To date, limited studies have focused on the time or dose required to achieve control of symptoms for paediatric patients. The median time to achieve control of symptoms is 2 weeks in our study.

All children between 0.5 to 2 years of age attained symptom control by 14 weeks, with 7 out of 95 patients who are greater than 2 years of age who were not well controlled after 14 weeks. Of these patients, 3 out of 37 were between 2 to 6 years of age while 4 out of 40 were greater than 6 years of age. According to a retrospective study conducted in Turkey study by Sahinder, females who are older than 10 years of age is a risk factor for a poorer prognosis of CSU and they generally took a longer time to attain symptom resolution [26].

Limitations

Not having adequate sample size and power in the different subgroups is a major limitation of this study. Another possible factor is the short follow-up period of 1 year for our CSU paediatric patients.

Conclusion

This study provides insights to the clinical characteristics of CSU paediatric patients in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. For this study, a weight-based antihistamine table was established to better guide physicians in the management of CSU patients at our specialist outpatient clinics. Since then, we have incorporated these tables for routine management of our patients with CSU. The antihistamine weight based titration table provides clinicians a safety dose check and it leads to a more systematic approach in the management of CSU in paediatric population. It is important to observe that majority of our patients can be controlled at steps 1 and 2 antihistamine doses without having to step up to 4 times the recommended dosing to achieve urticaria control. However, future studies are needed to assess the trend and factors associated with resolution of CSU in recalcitrant patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Helena Chi Hiu Ching and Anna Liza Sande Masarap for collecting the data.

References

- 1.Asero R. Chronic unremitting urticaria: is the use of antihistamines above the licensed dose effective? A preliminary study of cetirizine at licensed and above-licensed doses. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:34–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khakoo G, Sofianou-Katsoulis A, Perkin MR, Lack G. Clinical features and natural history of physical urticaria in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:363–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuchinda M, Srimaruta N, Habanananda S, Vareenil J, Assatherawatts A. Urticaria in Thai children. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 1986;4:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan AP. Angioedema. World Allergy Organ J. 2008;1:103–113. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e31817aecbe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volonakis M, Katsarou-Katsari A, Stratigos J. Etiologic factors in childhood chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1992;69:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheikh J. Autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor in chronic urticaria: how important are they? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:403–407. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000182540.45348.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy Y, Segal N, Weintrob N, Danon YL. Chronic urticaria: association with thyroid autoimmunity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:517–519. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.6.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma M, Bennett C, Cohen SN, Carter B. H1-antihistamines for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD006137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006137.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolen TM. Sedative effects of antihistamines: safety, performance, learning, and quality of life. Clin Ther. 1997;19:39–55. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Giménez-Arnau AM, Grattan CE, Kapp A, Maurer M, Merk HF, Rogala B, Saini S, Sánchez-Borges M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Schünemann H, Staubach P, Vena GA, Wedi B Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1427–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell RJ, Du Toit GL, Siddique N, Leech SC, Dixon TA, Clark AT, Mirakian R, Walker SM, Huber PA, Nasser SM British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) BSACI guidelines for the management of chronic urticaria and angio-oedema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:631–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Młynek A, Zalewska-Janowska A, Martus P, Staubach P, Zuberbier T, Maurer M. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy. 2008;63:777–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilic G, Guler N, Suleyman A, Tamay Z. Chronic urticaria and autoimmunity in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:837–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanani A, Schellenberg R, Warrington R. Urticaria and angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sussman G, Hebert J, Gulliver W, Lynde C, Waserman S, Kanani A, Ben-Shoshan M, Horemans S, Barron C, Betschel S, Yang WH, Dutz J, Shear N, Lacuesta G, Vadas P, Kobayashi K, Lima H, Simons FE. Insights and advances in chronic urticaria: a Canadian perspective. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2015;11:7. doi: 10.1186/s13223-015-0072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jirapongsananuruk O, Pongpreuksa S, Sangacharoenkit P, Visitsunthorn N, Vichyanond P. Identification of the etiologies of chronic urticaria in children: a prospective study of 94 patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:508–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, Baek S, Shin B, Yoon SY, Park SY, Lee T, Lee YS, Bae YJ, Kwon HS, Cho YS, Moon HB, Kim TB. Influence of initial treatment modality on long-term control of chronic idiopathic urticaria. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tay YK, Kong KH, Khoo L, Goh CL, Giam YC. The prevalence and descriptive epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in Singapore school children. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:101–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiragun M, Hiragun T, Mihara S, Akita T, Tanaka J, Hide M. Prognosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria in 117 patients not controlled by a standard dose of antihistamine. Allergy. 2013;68:229–235. doi: 10.1111/all.12078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asero R. Intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might precede by years the onset of chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1095–1098. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee AJ, Shek LP. Food allergy in Singapore: opening a new chapter. Singapore Med J. 2014;55:244–247. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2014065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kidon MI, Kang LW, Chin CW, Hoon LS, See Y, Goh A, Lin JT, Chay OM. Early presentation with angioedema and urticaria in cross-reactive hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs among young, Asian, atopic children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e675–e680. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kidon MI, Liew WK, Chiang WC, Lim SH, Goh A, Tang JP, Chay OM. Hypersensitivity to paracetamol in Asian children with early onset of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;144:51–56. doi: 10.1159/000102614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam WY, Yau EK. Reports on Scientific Meetings: 19th Regional Conference of Dermatology. Hongkong J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;19:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahiner UM, Civelek E, Tuncer A, Yavuz ST, Karabulut E, Sackesen C, Sekerel BE. Chronic urticaria: etiology and natural course in children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;156:224–230. doi: 10.1159/000322349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]