To the Editor:

Although rare, inherited lung diseases provide important insights into disease pathogeneses. The two most common, cystic fibrosis (CF) and alpha-1 antitrypsin (alpha-1 AT) deficiency, are both monogenic, autosomal recessive disorders. CF is a multisystem disease that manifests in the lung with severe bronchitis, increased susceptibility to infection, progressive bronchiectasis, and lung function decline, whereas alpha-1 AT deficiency manifests primarily as panacinar lower lung zone emphysema, sometimes accompanied by bronchiectasis (1). Although CF and alpha-1 AT deficiency are the most prevalent, highly penetrant mutations leading to lung disease, many other mutations have been mapped for more than 20 rare familial lung diseases with diverse manifestations, including cystic, bronchiectatic, fibrotic, pulmonary vascular, ventilatory, hyper-IgE, or hypereosinophilic phenotypes (see Table E1 in the online supplement) (2–5). In contrast to the monogenic disorders, smoking-induced lung disease is far more prevalent (6). Although the classic lung phenotypes associated with smoking are bronchitis and/or emphysema, other smoking-induced lung phenotypes are now recognized, including variable degrees of cystic, bronchiectatic, fibrotic, and pulmonary vascular phenotypes (7).

Because mutations lead to altered/absent gene expression in monogenic lung diseases, and as cigarette smoking is known to alter gene expression in lung cells, we hypothesized that smoking may affect the expression of genes involved in monogenic lung disorders, which might help explain the phenotypic diversity observed in cigarette smokers. One example of this concept is the smoking effect on alpha-1 AT protein function as a neutrophil elastase inhibitor: whereas alpha-1 AT deficiency is a relatively rare cause of emphysema, smoking induces a functional deficiency in the alpha-1 AT protein in the lower respiratory tract of smokers (8). Another example is that smoking induces dysfunction of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein in the respiratory tract and systemically (9).

Because the most common smoking-related disease phenotypes start in the small airway epithelium (SAE), we asked, Are genes associated with monogenic lung disorders expressed in the SAE, and if so, does smoking alter expression levels? To address this question, we first assessed expression levels of 93 genes associated with monogenic lung disorders (10) (Table E1) in 230 SAE samples (≥95% epithelial cells) obtained by bronchoscopic brushing, as previously described (11), from 87 healthy nonsmokers and 143 healthy smokers without clinical evidence of disease (normal lung function [FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, total lung capacity, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, 6-minute-walk test], chest X-ray, alpha-1 AT levels, HIV-negative; smoking was verified by urine cotinine [all nonsmokers, <5 ng/μl; smokers average 1,530 ± 1,066 ng/μl]). Of the 93 genes implicated in monogenic lung disorders, 92 were represented by 219 probesets on the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0 microarray (Santa Clara, CA), and robust multiarray average–normalized data (GEO: GSE63127; Partek Genomics Suite 6.6, St. Louis, MO) were assessed by genome-wide analysis of variance, corrected for hybridization kit, sex, age, and ethnicity. Significance was determined by P < 0.05 after correction using Partek “step-up,” Benjamini-Hochberg, for multiple comparisons. Of the 92 genes assessed by microarray, 86 genes were expressed in the SAE. As expected, genes involved in airway diseases (i.e., bronchiectasis, CFTR of CF) were expressed. Surprisingly, many genes implicated in nonairway lung diseases were also expressed in healthy SAE, including genes related to parenchymal cystic/emphysema phenotypes, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary vascular disease, and others (Table E1).

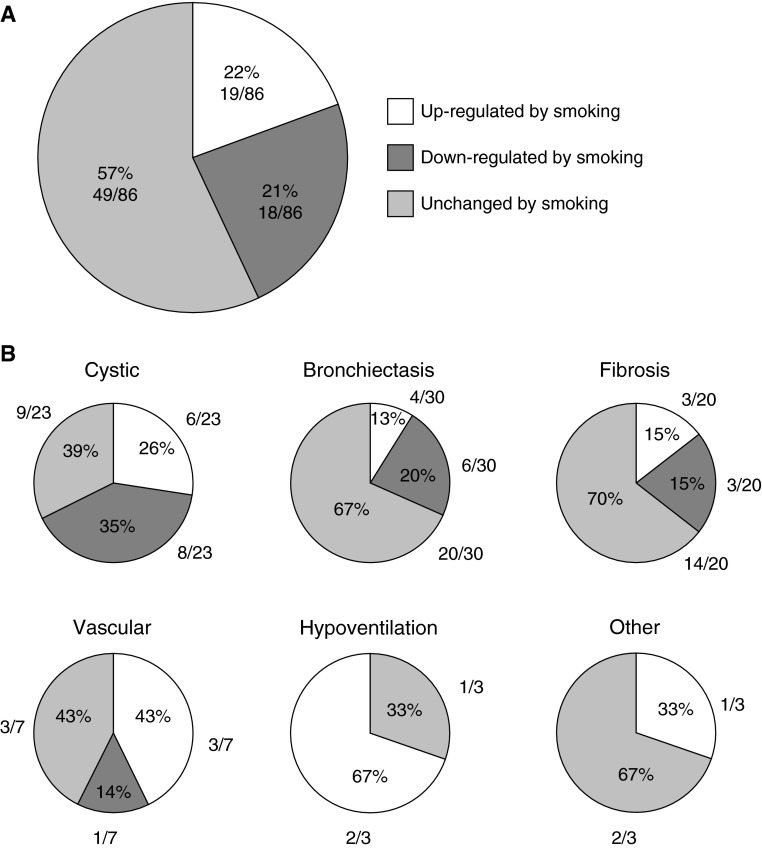

Assessing whether smoking alters expression of the 86 monogenic disease genes expressed in the SAE demonstrated that 37 (43%) of the genes were differentially expressed in healthy smokers versus healthy nonsmokers (P < 0.05; Table E1; Figure 1). In comparison, for 100 different random gene lists, an average of 26% of genes were differentially expressed (range, 0–42%; data not shown). Eighteen of the monogenic lung disorder genes (21%) were significantly down-regulated and 19 (22%) were significantly up-regulated in response to smoking, suggesting possible interplay between smoking effects and the function of monogenic lung disease-related genes. Among the 18 monogenic lung disorder-related genes suppressed by smoking, the category with the greatest proportion of affected genes was the cystic/emphysema category, with 8 (57%) of 14 genes down-regulated, including genes related to Ehlers Danlos (CHST14, COL5A2), cutis laxa (EFEMP2, FBLN5), Marfan syndrome (FBN1), Loey-Dietz (SMAD3, TGFBR2), and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (TSC1). Genes in other disease categories were also down-regulated by smoking, including primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) (ARMC4, DNAAF2, DNAH5, HEATR2, and OFD1), non-PCD bronchiectasis (SCNN1G), familial fibrosis (MUC5B), Hermansky-Pudlak (DTNBP1, HPS4), and pulmonary hypertension (BMRP2). Among the 19 monogenic genes up-regulated by smoking, the cystic/emphysema category had the greatest proportion of affected genes, including Ehlers Danlos (COL1A1, COL5A1, FKBP14, TNXB), cutis laxa (LTBP4), and alpha-1 AT deficiency (SERPINA1). Genes in other categories of monogenic lung disorders were also up-regulated by smoking, including PCD (DNAL1), CF (CFTR), non-PCD bronchiectasis (SCNN1A, SCNN1B), familial pulmonary fibrosis (ELMOD2), Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS1, AP3B1), pulmonary hypertension (ENG, KCNK3, SMAD9), hyper-IgE syndrome (DOCK8), and syndromic hypoventilation (ASCL1, RET).

Figure 1.

Monogenic lung disease-related genes with significant up- or down-regulation in the small airway epithelium (SAE) in response to smoking. The pie charts represent the percentage of total monogenic lung disorder-related genes that are expressed in SAE (86 genes expressed in SAE from cohort of n = 87 healthy nonsmokers and n = 143 healthy smokers), with shading representing overall response to smoking: no shading, up-regulated by smoking; dark gray shading, down-regulated by smoking; light gray shading, unchanged by smoking. (A) All monogenic lung disorder genes. (B) Separate categories of monogenic lung disorder genes for cystic, bronchiectasis, fibrosis, vascular, hypoventilation, and other lung phenotypes.

To validate the microarray data, RNA sequencing was performed in a subset of SAE samples (n = 5 nonsmokers; n = 6 smokers; NIH Short Read Archive: SRP005411), and fold-change (defined as mean expression in smokers/mean expression in nonsmokers) of significant smoking-responsive genes correlated between the two methods (r = 0.54; P < 10−15; not shown). Concordant directionality was observed for 64 (74%) of the 86 monogenic disorder-related genes expressed in the SAE.

In summary, monogenic lung disorder-related genes were expressed, and a substantial proportion (43%) were affected by cigarette smoking, in the SAE of healthy nonsmokers and smokers without clinical evidence of lung disease. Although fold-change differences were relatively small (median absolute fold change, 1.13; range, 1.06–1.58), the enrichment of differentially expressed genes for those implicated in a diverse set of monogenic lung diseases supports the notion that such genes are important to the maintenance of normal lung health in response to smoking, as they are expressed in healthy individuals. Several features support the hypothesis that altered expression in response to smoking may contribute to common smoking-related lung disease. First, consistent with the knowledge that emphysema is a common disease phenotype observed in smokers (12), cystic disease was the subcategory with the greatest proportion of genes affected by smoking. Second, although there were nearly equal numbers of up- and down-regulated genes in response to cigarette smoking, marked skewing of this distribution was observed within the bronchiectasis-causing subset of genes: five of six down-regulated genes are causes of PCD, whereas two of four up-regulated genes are CFTR and SCNN1A, whose gene products contribute to maintaining mucous viscosity. Down-regulation of ciliary apparatus genes may reflect a deleterious consequence of cigarette smoking, whereas up-regulation of genes responsible for maintaining mucous consistency may represent an attempt of the SAE to defend the local airway environment and facilitate airway clearance. Last, the differentially expressed genes implicated in pulmonary fibrosis (ELMOD2, MUC5B) and Hermansky-Pudlak (HPS1, HPS4, AP3B1, and DTNBP1) represent a candidate set of genes underlying the causal link between cigarette smoke exposure and the observed increased risk for interstitial lung abnormalities and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (13). The finding that healthy smokers had altered expression levels of genes involved in complex multisystem disorders such as hypoventilation and hypereosinophilic syndrome is surprising, and we propose that these findings may indicate novel functions for these gene products relevant to the pathogenesis of lung disease in smokers, a concept that requires further study.

Our study has limitations. Subsequent functional investigation is needed to determine how these genes may contribute to the pathogenesis of complex, smoking-related acquired lung disease. This is especially true for genes whereby loss-of-function mutations are implicated in the lung disorder but were up-regulated in healthy smokers in this study. In addition, only a subset of samples were confirmed by RNA sequencing. Bearing these limitations in mind, the data support the concept that genes implicated in rare monogenic lung diseases may have roles in the pathogenesis of smoking-related lung diseases and that smoking-induced changes in expression of these genes could be early molecular events in the development of diverse smoking-related clinical phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank N. Mohamed for help in preparing this manuscript and A. Rogalski, T. Sodeinde, and R. Rahim for technical help.

Footnotes

These studies were supported, in part, by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL107882 and P20 HL113443. A.E.T. was supported, in part, by NIH grant K23HL103837.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: A.E.T. and R.G.C.; data collection: A.E.T., M.R.S., J.S., B.V.d.G., and R.J.K.; data analysis: A.E.T., M.R.S., J.S., Y.S.-B., T.V., F.A.-P., J.G.M., B.A.R., and R.G.C.; drafting of the manuscript: A.E.T., M.R.S., J.S., B.V.d.G., B.A.R., and R.G.C.

This letter has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Crystal RG, Brantly ML, Hubbard RC, Curiel DT, States DJ, Holmes MD Clinical Consequences and Strategies for Therapy. The alpha 1-antitrypsin gene and its mutations: clinical consequences and strategies for therapy. Chest. 1989;95:196–208. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberts WM. Eosinophilic interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:419–424. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000130330.29422.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donabedian H, Gallin JI. The hyperimmunoglobulin E recurrent-infection (Job’s) syndrome: a review of the NIH experience and the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62:195–208. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitaichi M, Nishimura K, Itoh H, Izumi T. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a report of 46 patients including a clinicopathologic study of prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:527–533. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierson DM, Ionescu D, Qing G, Yonan AM, Parkinson K, Colby TC, Leslie K. Pulmonary fibrosis in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: a case report and review. Respiration. 2006;73:382–395. doi: 10.1159/000091609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stämpfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:377–384. doi: 10.1038/nri2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morse D, Rosas IO. Tobacco smoke-induced lung fibrosis and emphysema. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:493–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadek JE, Fells GA, Crystal RG. Cigarette smoking induces functional antiprotease deficiency in the lower respiratory tract of humans. Science. 1979;206:1315–1316. doi: 10.1126/science.316188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raju SV, Jackson PL, Courville CA, McNicholas CM, Sloane PA, Sabbatini G, Tidwell S, Tang LP, Liu B, Fortenberry JA, et al. Cigarette smoke induces systemic defects in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1321–1330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0733OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raby BA, Toledo D, Yonker LM, Henske E, Kinane TB. A multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation and care of patients with inherited lung disease [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A2774. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey BG, Heguy A, Leopold PL, Carolan BJ, Ferris B, Crystal RG. Modification of gene expression of the small airway epithelium in response to cigarette smoking. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0103-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washko GR, Hunninghake GM, Fernandez IE, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Yamashiro T, Ross JC, Estépar RS, Lynch DA, Brehm JM, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:897–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]