Abstract

DNA polymerase III (DNA pol III) is a multi-subunit replication machine responsible for the accurate and rapid replication of bacterial genomes, however, how it functions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) requires further investigation. We have reconstituted the leading-strand replication process of the Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme in vitro, and investigated the physical and functional relationships between its key components. We verify the presence of an αβ2ε polymerase-clamp-exonuclease replicase complex by biochemical methods and protein-protein interaction assays in vitro and in vivo and confirm that, in addition to the polymerase activity of its α subunit, Mtb DNA pol III has two potential proofreading subunits; the α and ε subunits. During DNA replication, the presence of the β2 clamp strongly promotes the polymerization of the αβ2ε replicase and reduces its exonuclease activity. Our work provides a foundation for further research on the mechanism by which the replication machinery switches between replication and proofreading and provides an experimental platform for the selection of antimicrobials targeting DNA replication in Mtb.

In spite of extensive efforts, tuberculosis (TB), caused by the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains a significant global public health threat1; in 2013, there were 9 million incident cases of TB and 1.5 million deaths2. The situation is further aggravated by the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug resistant (XDR) TB, co-infection with HIV, and the low efficacy of the Bacille-Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine3. There is an urgent need for new drugs. DNA polymerase III (DNA pol III), responsible for chromosomal DNA replication in all eubacteria including Mtb4, plays an important role in bacterial proliferation and is thus a significant and promising drug target; however, its mechanism in Mtb requires further investigation.

The DNA polymerase III system of Mtb is a large multisubunit machine, containing at least 6 subunits; α, ε, β, τ/γ, δ and δ′5. Genes encoding these subunits have been annotated in the Mtb genome, but the θ, χ and ψ subunits present in E. coli DNA Pol III, the most extensively studied model of DNA pol III, are absent in Mtb as in most other Gram-positive bacteria4,6. While only one α subunit (DnaE) is present in E. coli DNA pol III, two distinct homologues of the E. coli α subunit, DnaE1 and DnaE2, have been identified in the Mtb genome7. DnaE2 (also named ImuC) is a nonessential error-prone polymerase8,9, and DnaE1 is considered to be the DNA polymerase responsible for faithful genome replication. A 3-D structural model of Mtb α (MtbDnaE1) in complex with a small molecule inhibitor confirmed its structural differences from the human genomic replicase, and thus its promise as a drug target10. The crystal structure of the β2 clamp, the classical processive factor of DNA pol III, has been solved in Mtb at resolutions of 2.89 Å11 and 3.00 Å12, likewise confirming its close homology, including binding sites for α and other subunits, with the β2 clamp of E. coli. Little, however, is known about the structure and function of the other subunits of Mtb DNA pol III.

The functional efficiency of DNA pol III is determined by its replication rate, fidelity and processivity, characteristics that affect bacterial proliferation rates and the frequency of mutations in genes and intergenic regions which lead to drug-resistance13. The replicative fidelity of DNA pol III, determined by base selection by the α polymerase14 and editing of polymerase errors by proofreading factor(s)15, is of great importance in Mtb as it lacks a DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system16. Based on studies in E. coli, the proofreading activity of bacterial DNA Pol III has long been attributed to the ε exonuclease, a 3′–5′ exonuclease bound to the α subunit17, which increases its replication fidelity by about 102–103 fold18. However, accumulating evidence suggests that exonuclease activity residing in the PHP (polymerase and histidinol phosphatase) domain of the α subunit of many bacteria may actually be the ancestral prokaryotic proofreader19,20,21. Rock et al. recently reported that this αPHP domain exonuclease activity is responsible for proofreading during DNA replication in Mtb and appears to eliminate any role for mycobacterial DnaQ homologues under standard culture conditions in vitro21. However, which of these two exonuclease activities (ε and α) fulfills the proofreading role in Mtb DNA pol III in vivo, or whether both may be involved, requires further investigation. A delicate balance between the exonuclease activity of DNA pol III and its polymerase activity is necessary to maintain both its replicative rate and fidelity. In E. coli this balance is achieved as the αεθ:β2 replicase complex, formed when the αεθ core of DNA pol III associates with the β2 clamp, switches between polymerization and proofreading modes22,23,24 and the interactions between the α, ε and β2 subunits, especially the ε-β2 interaction, likely play an important role in this switch22,23. The physical and functional interactions between α, ε and β2 in Mtb DNA pol III and the mechanism by which Mtb DNA pol III regulates the balance between polymerase and exonuclease activity remain to be elucidated.

Here, in order to characterize Mtb DNA pol III, we reconstituted the leading-strand replication process of the Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme in vitro and used standard protein-protein interaction assays and exonuclease and primer-extension assays to investigate the physical and functional relationships between its key components. We show that β2 may play an important bridging role between α and ε, both of which have ssDNA exonuclease activity and may serve as proofreading subunits. Our findings provide important insights into the mechanism by which Mtb DNA pol III transitions between polymerization and proofreading modes; the presence of the β2 clamp contributes to maintaining the αβ2ε replicase in polymerization mode and conditions required for ongoing polymerization (i.e. the presence of adequate amounts of dNTPs) may be essential for the transition from proofreading to polymerization mode.

Results

Reconstitution of leading-strand replication by Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme

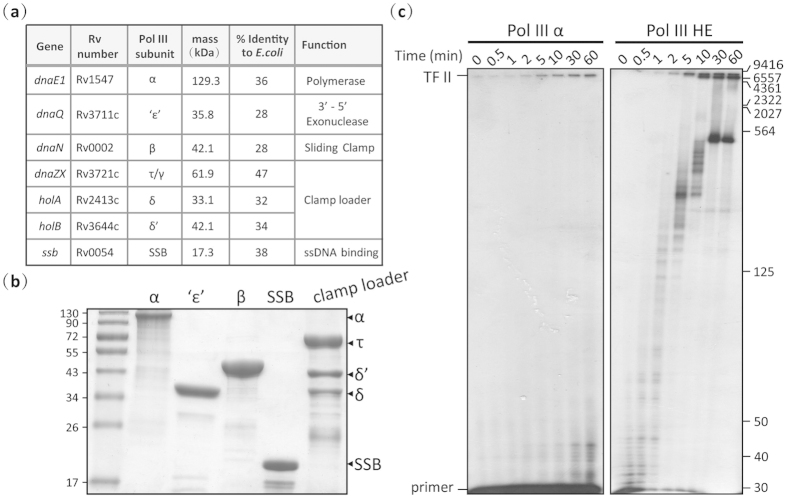

Genes corresponding to typical DNA Pol III subunits (α (dnaE1), ε (dnaQ), β (dnaN), τ (dnaZX), δ (holA), δ’ (holB), and SSB (ssb)) have been annotated in the Mtb genome5 (Fig. 1a)25; however, with the exception of the α10,21 and β subunits11, little functional information is available. In E. coli, the subunits of DNA pol III are organized into three functional parts: the polymerase core (αεθ), a ring-shaped sliding-clamp (β2) and a clamp loader (τ2γδδ’ ψχ)4. To maintain high efficiency, the main catalytic α subunit of E. coli DNA pol III has to interact with other subunits, such as ε17, β24, τ26 and SSB27, to form a holoenzyme. Here, we purified these Mtb DNA Pol III subunits (Supplementary Experimental Methods; Fig. 1b) and reconstituted the leading-strand replication activity of the Mtb holoenzyme. All subunits expressed well in E. coli, however, unlike the dnaX gene in E. coli which encodes two subunits, γ and τ, the Mtb dnaZX gene expressed in E. coli only produced one protein, the τ subunit. In addition, cells expressing τ, δ, and δ’ had to be co-lysed in order to purify a stable clamp loader complex. Densitometric scanning of an SDS-PAGE gel indicated that τ, δ and δ’ were present in a 3:1:1 ratio in the clamp loader complex, as in E. coli28. To further verify the integrity and activity of our Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme, we reconstituted leading-strand replication using a M13mp18 ssDNA template (7249 bp). While Mtb α on its own could catalyze the DNA extension reaction (Fig. 1c, left panel), confirming that it is the main catalytic subunit, a highly efficient DNA polymerase with high rate and processivity was only reconstituted in the presence of the other DNA pol III components (Fig. 1c, right panel).

Figure 1. Purification of the protein subunits of the Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme and reconstitution of leading-strand replication.

(a) Gene name, mass and predicted function of Mtb DNA Pol III subunits, and their percent identity to corresponding subunits in the E. coli Pol III system25. (b) Coomassie Blue-stained 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel of the purified DNA pol III holoenzyme subunits. The positions of subunits in the gel are indicated by arrows. All purified proteins were verified by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). (c) Reconstitution of leading-strand replication by the α subunit alone (left panel) and by the holoenzyme (right panel). The position of the fully extended M13mp18 DNA (TF II, 7249 bp) is indicated on the left. Size markers are shown on the right. Results presented are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

Mtb DNA Pol III ‘ε’ is a Mg2+-dependent exonuclease with a preference for ssDNA

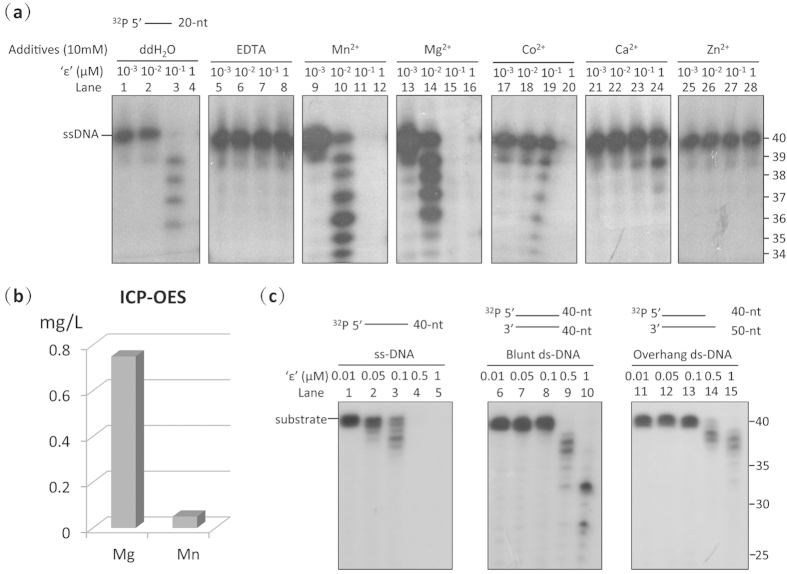

We next examined whether Rv3711, the most likely Mtb homologue of the ε proofreading subunit of E. coli DNA pol III (hereafter referred to as ‘ε’) has exonucleolytic activity as recently reported21. Sequence alignment of Rv3711 with ε homologues from other bacteria indicated that it has a highly conserved exonuclease active site containing six residues (D20, E22, D104, R155, H158 and D163) in its N-terminal domain (Supplementary Fig. S1). Assaying the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ using 5′-labelled single-stranded DNA indicated that, similar to the E. coli ε exonuclease29, ‘ε’ has 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease activity that is inhibited by EDTA (Fig. 2a, Lanes 1–8), indicating that its activity is likely divalent metal ion-dependent. Subsequent experiments indicated that ‘ε’ is strongly activated in the presence of Mn2+ and Mg2+, and its exonuclease activity is slightly higher in the presence of Mn2+ than Mg2+ (Fig. 2a, Lanes 9–16), in agreement with previous studies on E. coli ε29,30, while its activity decreased to different degrees in the presence of Co2+, Ca2+ and Zn2+ (Fig. 2a, Lanes 17–28). To further clarify the importance of Mn2+ and Mg2+ in the exonuclease activity of native ‘ε’, we measured the quantities of these ions in ‘ε’ using ICP-OES. The quantity of Mg2+ was about one order of magnitude greater than that of Mn2+ in native ‘ε’ (Fig. 2b), indicating that the metal ions in the active site of Mtb ‘ε’, as in E.coli ε30, are Mg2+ ions rather than Mn2+ ions.

Figure 2. The ‘ε’ subunit of Mtb DNA pol III has exonuclease activity.

(a) Ion dependency of the exonuclease activity of the ‘ε’ subunit. The ‘ε’ subunit is a 3′–5′ exonuclease which is activated by Mg2+ and Mn2+, and inhibited by EDTA, Co2+, Ca2+and Zn2+. (b) ICP-OES quantitation of metal ions in the purified ‘ε’ subunit. The native ‘ε’ subunit binds significantly more Mg2+ (~0.75 mg/L) than Mn2+ (less than 0.05 mg/L), and is thus a Mg2+-dependent exonuclease. The mean of three replicate samples analysed is shown. (c) The exonuclease activity of the ‘ε’ subunit shows a preference for ssDNA over blunt-dsDNA or 5′ overhanging-dsDNA as substrate. Substrate types are shown above each panel. Results presented are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

When we examined the substrate preference of ‘ε’, results indicated that ‘ε’ excises the 3′-terminus of single-stranded DNA considerably faster (Fig. 2c, Lanes 1–5) than that of paired dsDNA, irrespective of whether the dsDNA had a blunt end or 5′-overhang (Fig. 2c, Lanes 6–15). The Mtb ‘ε’ exonuclease thus has a preference for ssDNA, and is probably involved in proofreading.

Mtb DNA Pol III α has exonuclease as well as polymerase activity

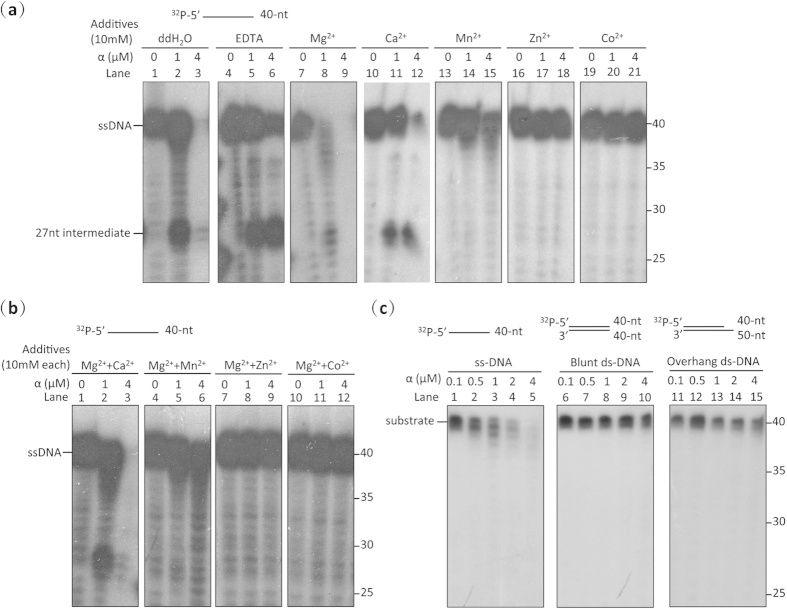

Accumulating evidence also points to the presence of a highly conserved exonuclease active site in the PHP domain of the α subunit of bacterial DNA pol III19,20,21. Initial evidence from a study on the α subunit of T. thermophilus DNA pol III which showed it to have an intact exonuclease active site in its PHP domain and Zn2+-dependent exonuclease activity, suggested that it may be the proofreading subunit of DNA pol III19. A recent phylogenetic analysis of α and ε homologues across the bacterial kingdom indicated that the majority of replicative bacterial polymerases contain an active PHP exonuclease site in the α subunit while E. coli-like ε exonucleases appear to be unique to the α-, β- and γ-proteobacteria21. Sequence alignment of the Mtb α subunit with that of other bacteria here (Supplementary Fig. S2) confirmed the presence of an intact PHP exonuclease active site consisting of nine residues (H14, H16, D23, H48, E73, H107, C158, D226 and H228), and exonuclease activity assays using 5′-labelled single-stranded DNA verified that it has 3′–5′ exonuclease activity (Fig. 3a, Lanes 1–3), confirming that, in addition to its polymerase activity, Mtb α is likely also involved in proofreading21. In contrast to ‘ε’, the exonuclease activity of α was not absolutely inhibited by a large excess of EDTA (Fig. 3a, Lanes 4–6). It was, however, strongly activated by the addition of Mg2+ (Fig. 3a, Lane 7–9), indicating that it is a Mg2+-activated 3′–5′ DNA exonuclease. The observed exonuclease activity was inhibited completely by Zn2+ (Fig. 3a, Lanes 16–18), and to lesser degrees by the other metal ions tested (Ca2+, Mn2+, Zn2+ and Co2+) (Fig. 3a, Lanes 10–21). The catalytic divalent ions residing in the PHP domain of Mtb α (pol III) are thus most likely to be Mg2+ rather than Zn2+ as is the case for α (pol III) in T. thermophilus19 or Mn2+ as is the case in the Pol X of T. thermophilus31 and B. subtilus32. These results eliminate any possibility that the Mtb α subunit used here became contaminated with E. coli ε subunits during protein purification; EDTA only partially inhibited the exonuclease activity of the Mtb α subunit (Fig. 3a, Lanes 4–6) while it is known to completely inhibit the exonuclease activity of E. coli ε29, and while E. coli ε is known to be activated by Mn2+ 30, the exonuclease activity of Mtb α was considerably inhibited by Mn2+ (Fig. 3a, Lanes 13–15). In addition, cleavage of DNA by the α exonuclease showed a temporary pause at ~27 nt (Fig. 3a, Lane 2), coincident with the length of DNA occupied by the α subunit20, further demonstrating that the exonuclease activity arose from Mtb α. To rule out the possibility that the reduction in exonuclease activity of Mtb α observed here in the presence of each ion tested (except Mg2+) resulted from conformational change due to coordination of insufficient Mg2+ ions in the Palm polymerase active site, we measured its exonuclease activity in the presence of the tested ions (Ca2+, Mn2+, Zn2+ and Co2+) in combination with Mg2+. Sensitivity of the exonuclease activity to the tested ions was barely affected by the presence or absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 3a, Lanes 10–21; and Fig. 3b), indicating that α exonuclease activity is directly inhibited by the four ions themselves.

Figure 3. The α subunit of Mtb DNA Pol III has exonuclease activity.

(a) Exonuclease assays indicate that the α subunit is a 3′–5′ exonuclease which is activated by Mg2+, and inhibited by EDTA, Ca2+, Mn2+, Zn2+ and Co2+. (b) Assay of the exonuclease activity of the α subunit in the presence of Mg2+ combined with other divalent metal ions. The presence of Mg2+ does not affect the sensitivity of the exonuclease activity of the α subunit to Ca2+, Mn2+, Zn2+ or Co2+. (c) The DNA Pol III α subunit is a single-stranded DNA exonuclease as determined by assays using ssDNA, blunt-dsDNA or 5′ overhanging-dsDNA as substrates. Substrate types are shown above each panel. Results presented are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

We next examined the substrate preference of the α exonuclease. Results indicated that α preferentially hydrolyses ssDNA rather than matched duplex DNA (Fig. 3c), further supporting its proposed role for removing mispaired-nucleotides. Since degradation of all radioactive ssDNA substrates was accomplished here at much lower concentrations of ‘ε’ (Fig. 2c, Lane 4) than of α (Fig. 3c, Lane 5), the exonuclease activity of Mtb ‘ε’ appears to be higher under the experimental conditions used here than that of α. Taken together, then, these findings indicate that Mtb DNA Pol III α and ‘ε’ may both fulfill proofreading roles.

The α polymerase, ‘ε’ exonuclease and β clamp physically interact with each other in Mtb to form an αβ2 ‘ε’ replicase

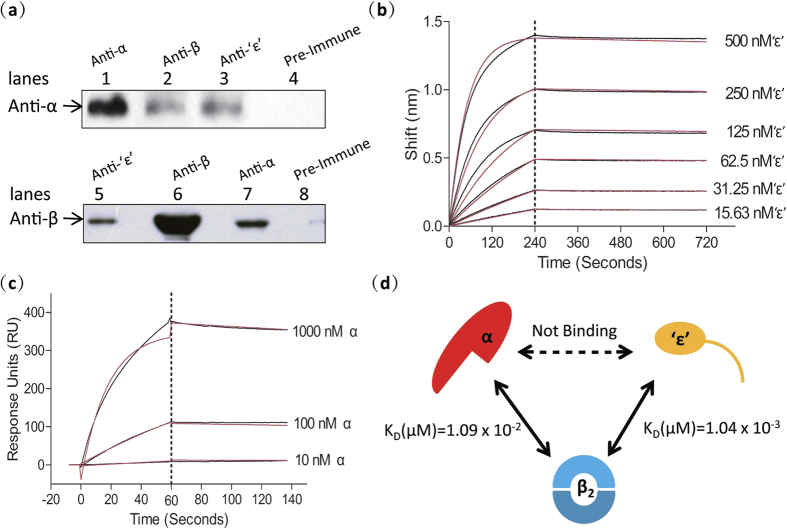

As the presence of a proofreading ε subunit in E. coli and other α-, β- and γ-proteobacteria is correlated with a defective PHP domain in the α subunit, there is debate as to whether an ε exonuclease and αPHP exonuclease can co-exist19,21,33. However, a recent bioinformatic analysis reported the presence of an intact PHP active site and a conserved putative ε-binding patch on the surface of the PHP domain in the DNA pol III of bacteria such as the Firmicutes, supporting the possibility of co-existence7. To determine whether the exonuclease activity of the α and ‘ε’ subunits is mutually exclusive in Mtb we first investigated the physical interactions between α, ‘ε’ and β2 in vivo by co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and in vitro by Biolayer interference (BLI), Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). Co-IP confirmed that α, ‘ε’ and β2 interact with each other, likely forming an αβ2 ‘ε’ ternary complex in vivo (Fig. 4a) similar to the αεθ:β2 replicase of E. coli34. BLI and ITC results, however, indicated that ‘ε’ does not interact with α, (Supplementary Fig. S3), in contrast to the situation in E. coli where stable α-ε complexes have been purified17, but in agreement with recent findings by Rock et al.21. To investigate why the α-ε interaction disappears in Mtb, we aligned the sequences of these subunits with those of their homologues in other bacteria. Sequence alignments suggest that while the hydrogen bond between ε-H255 and α-K63 involved in the α-ε interaction in E. coli7 is conserved in Mtb, a tryptophan in Mtb ‘ε’ in an analogous position to the ε-Trp241 in E. coli which binds to the αPHP domain is absent, providing a possible explanation for the loss of the α-‘ε’ interaction (Supplementary Fig. S1). We reason that the conflicting results obtained here using Co-IP and BLI may be explained by the existence of a bridging protein that tightly couples α and ‘ε’. BLI results indicate that Mtb ‘ε’ binds tightly to β2 with a KD of 1.04 × 10−3 μM, an interaction that is five orders of magnitude stronger than that found in E. coli (KD = ~200 μM)22 (Fig. 4b). To identify the residues of ‘ε’ responsible for the interaction with β2, we analyzed the ‘ε’ sequence using PSIPRED and DISOPRE; the C-terminal segment of ‘ε’ is predicted to be disordered and capable of binding proteins (Supplementary Fig. S4). Likewise, Mtb α binds to β2 with a KD (1.09 × 10−2 μM) that is much stronger than that reported for the binding of α to β2 in E. coli (KD = 1.2 ± 0.2 μM)35,36 (Fig. 4c). These results thus suggest that β2 is associated with both α and ‘ε’, and likely plays an important bridging role in the formation of an αβ2‘ε’ replicase in Mtb (Fig. 4d). These interactions between α, ‘ε’ and β2 also imply that the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ and the PHP domain of α are not exclusive, further confirming that they are both potential proofreading factors in Mtb DNA Pol III.

Figure 4. The subunits of the αβ2‘ε’ complex of Mtb DNA pol III interact physically both in vitro and in vivo.

(a) Physical interactions between α, β2 and ‘ε’ as determined by Co-IP. Sera incubated with cell lysate supernatants are indicated above the panels. Sera used as primary antibodies in Western blotting are indicated on the left. Lanes 4 and 8 are negative controls. Lanes 1 and 6 are positive controls and confirm the specificity of the anti-α and anti-β sera. (b) Kinetics of the ‘ε’-β interaction (KD = 1.04 × 10−3 μM) as determined by BLI using six concentrations of the ‘ε’ subunit (15.63, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 nM). Black lines represent the data before fitting, and red lines represent the global fit of the entire data set to a 1:1 Langmuir interaction model. (c) Kinetics of the α-β interaction (KD = 1.09 × 10−2 μM) as determined by SPR using three concentrations of the α subunit (0.01, 0.1 and 1 μM). Black lines represent the data before fitting, and red lines represent the global fit of the entire data set to a 1:1 Langmuir interaction model. (d) Diagram showing the protein interactions between the subunits of the αβ2‘ε’ complex and their kinetic parameters determined in vitro. While the α subunit does not bind to the ‘ε’ exonuclease subunit, they are both tightly bound to the β2 clamp. Results presented are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

Equimolar mixtures of Mtb DNA Pol III α and ‘ε’ exhibit unexpected exonuclease activity on paired duplex DNA in vitro

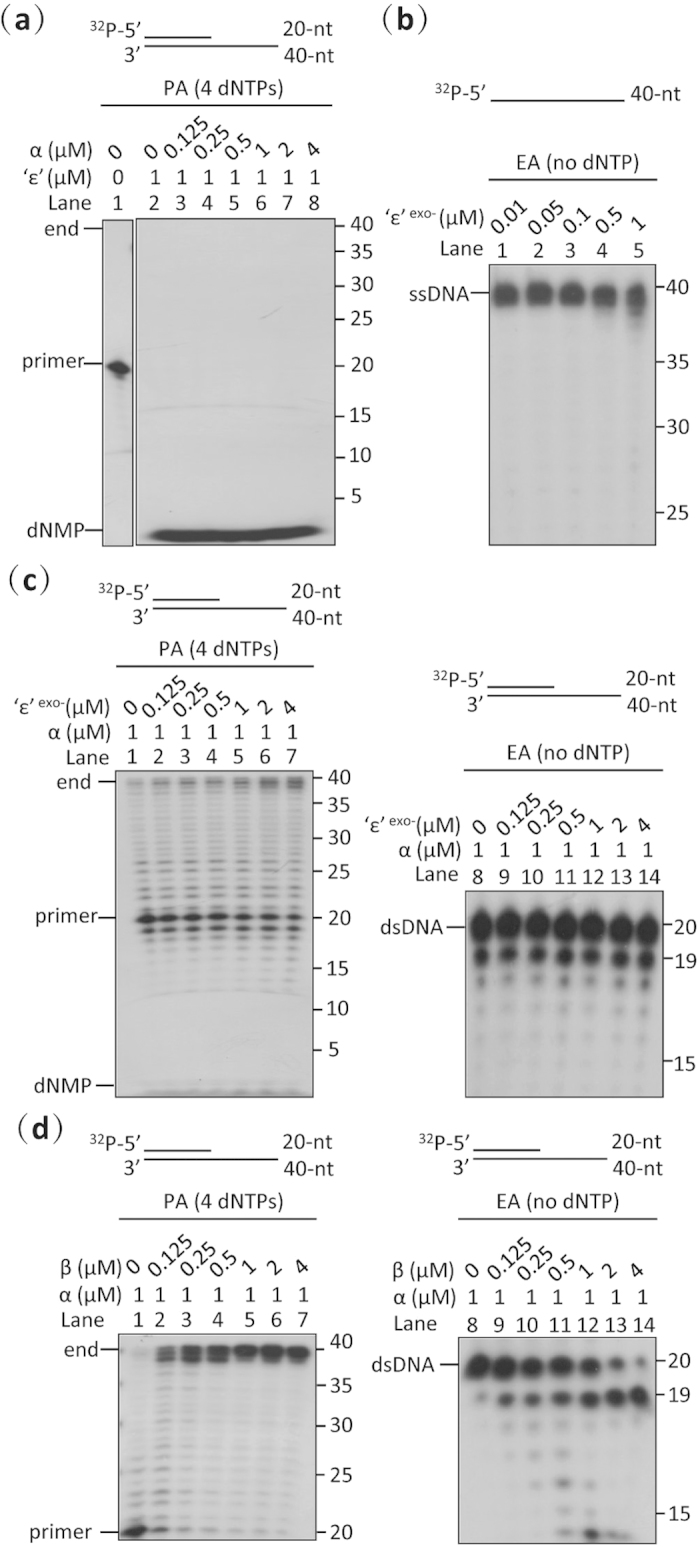

We next investigated whether, as in E. coli, Mtb α and ‘ε’ together might execute both polymerase and exonuclease activities. While the reconstituted E. coli αε core chiefly exhibits polymerase activity37, an equimolar mixture of Mtb α and ‘ε’ showed unexpectedly strong exonuclease activity on paired dsDNA and no polymerase activity (Fig. 5a, Lane 6). No primer extension was observed even when the molar ratio of α and ‘ε’ was increased to 4:1 (Fig. 5a, Lane 8). To verify which subunit was responsible for this unexpectedly strong exonuclease activity, we replaced the D20, E22 and D104 residues in the active site of ‘ε’ with alanine to destroy its exonuclease activity (Fig. 5b). When wild-type ‘ε’ (‘ε’WT) in the mixture was replaced by this ‘ε’exo- mutant, the equimolar α-‘ε’exo- mixture extended the primed DNA substrate and failed to fully degrade paired dsDNA into dNMP, even though it could still slowly remove nucleotides from the 3′ terminus (Fig. 5c, Lane 5). This indicates that the strong exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture likely arises from ‘ε’ rather than α and that the weak exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’exo- mixture is likely catalyzed by α.

Figure 5. Investigation of the functional interactions between the subunits of the αβ2‘ε’ complex of Mtb DNA pol III.

(a) Primer-extension assay of different ratios of α and ‘ε’ subunits using a primed dsDNA substrate. Mixtures of α and ‘ε’ subunits exhibit unexpectedly high exonuclease activity on paired duplex DNA and no polymerase activity in vitro. Increasing amounts of the α subunit fail to weaken the exonuclease activity of the ‘ε’ subunit in vitro. (b) Exonuclease assay of the ‘ε’ mutant (‘ε’exo-) using a ssDNA substrate. Mutation of the active site of the ‘ε’ subunit (D20A, E22A and D104A) successfully destroys its exonuclease activity. (c) Primer-extension and exonuclease assays of the α subunit with increasing amounts of ‘ε’-exo using a primed dsDNA substrate. The ‘ε’-exo mutant modestly enhances the polymerase activity of the α subunit (left panel), but has no effect on its exonuclease activity (right panel). (d) Primer-extension and exonuclease assays of the α subunit with increasing amounts of β2 clamp using a primed dsDNA substrate. While the polymerase activity of the α subunit is strongly promoted by the presence of the β2 clamp (left panel), its exonuclease activity is only slightly increased (right panel). The reaction conditions of the polymerase (PA) and exonuclease assays (EA) were the same, except that the 4 dNTPs were omitted in the exonuclease assay. The primed dsDNA substrate was produced by annealing a 5’-32P-labeled ssDNA primer (20-mer) to an unlabeled ssDNA template (40-mer). Results presented are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

To understand the influence of ‘ε’ on the function of α, we examined the polymerase and exonuclease activities of α in the presence of increasing amounts of ‘ε’exo-. The presence of ‘ε’ (εexo-) considerably enhanced the polymerase activity of α (Fig. 5c, left panel), in agreement with results from E. coli37,38. In contrast, the exonuclease activity of α was not affected by the addition of ‘ε’exo- at concentrations of 0.125 μM to 4 μM (Fig. 5c, right panel), suggesting that the exonuclease activity of α, either alone or when together with ‘ε’, is not as strong as that of the equimolar α-‘ε’WT mixture.

Given the tight physical interaction between α and β2, we investigated whether β2 has any direct influence on the exonuclease or polymerase activity of α. Increasing the concentration of β2 markedly increased the polymerase activity of α (Fig. 5d, left panel), mimicking the effect seen in E. coli39,40. On the other hand, the exonuclease activity of α increased only slightly in the presence of β2 (Fig. 5d, right panel). In addition, the α exonuclease only removed one nucleotide from the 3′ end of the DNA (Fig. 5d, right panel) and, unlike the ‘ε’ exonuclease, failed to further digest the DNA into dNMPs (Fig. 5a).

Taken together, these results indicate that, in addition to the observed physical ‘ε’-β2 and α-β interactions, ‘ε’ and β2 also interact functionally with α, enhancing its polymerase activity, with β2 promoting its polymerase activity to a greater extent than ‘ε’.

β2 simultaneously promotes the polymerase and reduces the exonuclease activity of the αβ2‘ε’ replicase

Although Mtb ‘ε’ exhibits a distinct preference for mispaired DNA over paired DNA, as shown above, an equimolar α-‘ε’WT mixture was still capable of rapidly degrading paired DNA (Fig. 5a, Lane 6). We thus hypothesized that there must be an underlying mechanism by which the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ is modulated when it is in association with other subunits in a DNA Pol III subassembly or holoenzyme in the active replication fork.

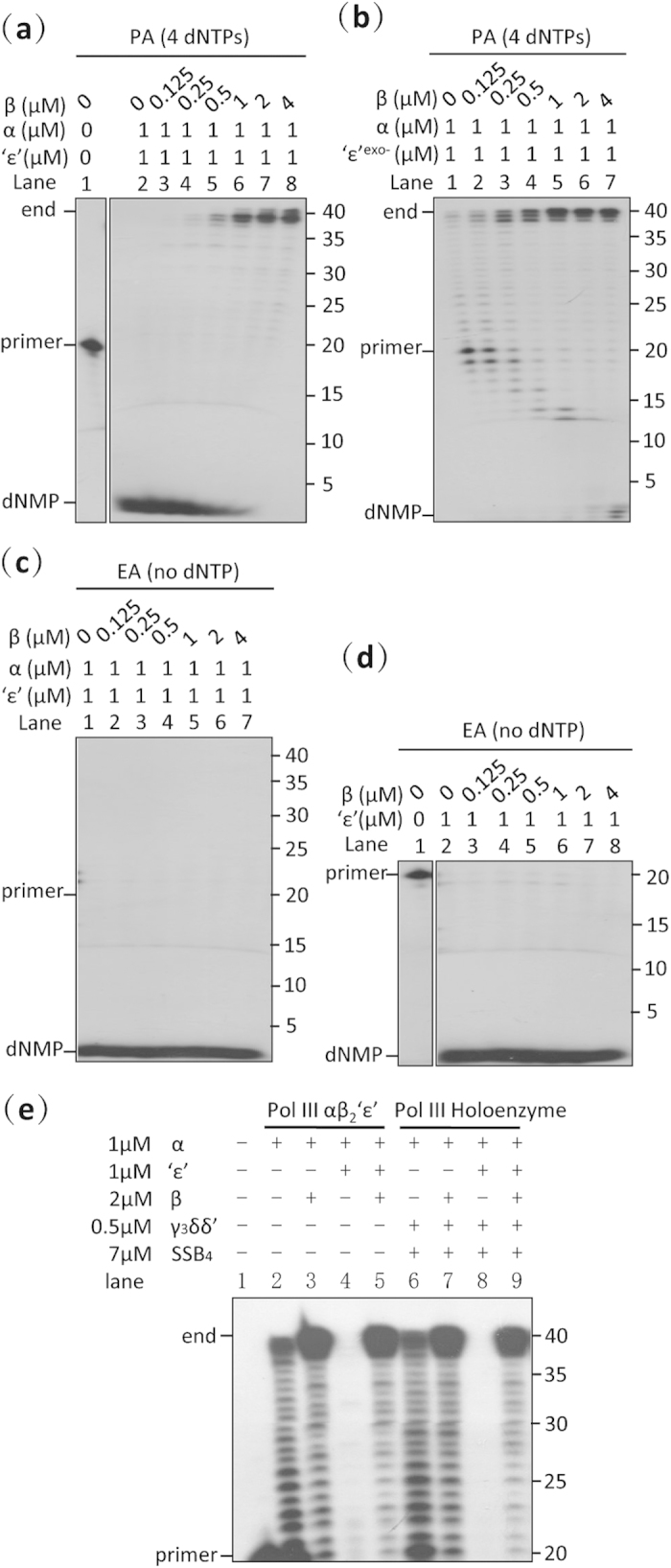

To determine whether the β2 clamp might play a role in regulating the polymerase/exonuclease activity of DNA polymerase III in addition to its bridging role in physically integrating α and ‘ε’ to stabilize the αβ2‘ε’ replicase, we examined the effect of gradually increasing the amount of β2 on the exonuclease and polymerase activity of an α-‘ε’WT mixture. Gradually increasing the amount of β2 enhanced the polymerase activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture and reduced its exonuclease activity (Fig. 6a), indicating that the formation of the αβ2‘ε’ replicase complex leads to increased polymerase over exonuclease activity, and suggesting that the interaction of α and ‘ε’ with β2 may be indispensable for guaranteeing rapid DNA replication.

Figure 6. Role of the β2 clamp in the αβ2‘ε’ complex of Mtb DNA pol III.

(a) Primer-extension assay of the αβ2‘ε’ replicase. The β2 clamp strongly promotes the polymerization and reduces the exonuclease activity of the αβ2‘ε’ complex. (b) Primer-extension assay of the αβ2‘ε’exo- replicase. Once the exonuclease activity of the ‘ε’ subunit is mutated, the β2 clamp promotes the polymerase activity, and very slightly enhances the exonuclease activity of the αβ2‘ε’exo- replicase. (c) Exonuclease assays of the αβ2‘ε’ replicase. Increasing the amount of the β2 clamp does not reduce the exonuclease activity of the αβ2‘ε’ complex in the absence of the 4 dNTPs. (d) Exonuclease assays of different ratios of ‘ε’ and the β2 clamp. Increasing the amount of the β2 clamp fails to directly preclude the exonuclease activity of the ‘ε’ subunit in vitro. (e) Primer-extension assay of Mtb DNA pol III subassemblies. Equimolar mixtures of the α and ‘ε’ subunits exhibited only exonuclease activity, both in the presence (holoenzyme) and absence (αβ2‘ε’) of the clamp loader and SSB, and the presence of the β2 clamp reduced exonuclease activity and restored polymerase activity. The reaction conditions of the polymerase (PA) and exonuclease assays (EA) were the same, except that the 4 dNTPs were omitted in the exonuclease assay. The primed dsDNA substrate used in all the above experiments was produced by annealing a 5′-32P-labeled ssDNA primer (20-mer) to an unlabeled ssDNA template (40-mer). Results presented are representative of at least three replicate experiments.

To determine if the enhanced polymerase activity of the αβ2‘ε’ replicase is directly linked to decreased exonuclease activity, we repeated the above experiment using the ‘ε’exo- mutant. The polymerase activity of the α-‘ε’exo- mixture was stimulated in the presence of β2 as was the case for the α-‘ε’WT mixture (Fig. 6b), and the exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’exo- mixture also increased slightly (Fig. 6b). These findings indicate that promotion of the α-‘ε’WT mixture polymerase activity by β2 likely does not rely directly on a decline in the exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture. In addition, they suggest that the gradual enhancement of DNA synthesis observed with increasing amounts of β2 is due to the direct stimulation of the polymerase activity of α by β2 (Fig. 5d left panel) discussed above. The decline in exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture in the presence of β2, then, is likely due to the β2 clamp directly or indirectly blocking the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ rather than α; the reduced exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’exo- mixture failed to fully degrade the dsDNA substrate into dNMP, even in the presence of β2 (Fig. 6b). We further investigated the effect of the β2 clamp on ‘ε’ by examining the effect of increasing amounts of β2 on ‘ε’ in the absence of α. Results indicate that β2 does not directly inhibit the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ in the absence of α (Fig. 6d).

Next, to investigate if there is a direct relationship between the decrease in the exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture and the increase in its polymerase activity on addition of the β2 clamp, we blocked polymerase activity by omitting the four dNTPs. Interestingly, when all four dNTPs were removed, increasing the amount of β2 did not reduce the exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture (Fig. 6c). To rule out the possibility that the dNTPs might somehow contribute to the decrease in exonuclease activity, we repeated the experiment using dGTP to replace the four dNTPs; the presence of β2 still failed to reduce the exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture (data not shown). The decrease in exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’WT mixture in the presence of β2 thus appears to be directly linked to active ongoing DNA polymerization catalyzed by α.

To determine whether the direct regulatory effect of β2 on polymerization and exonuclease activity occurs in both the αβ2‘ε’ complex and the holoenzyme of the Mtb DNA pol III, we examined the polymerase and exonuclease activity of the αβ2‘ε’ complex in the presence of SSB and the β2 clamp loader. Exonuclease activity of the α-‘ε’ mixture was reduced in the presence of the β2 clamp and its polymerase activity was restored in both the αβ2‘ε’ complex and the holoenzyme of the Mtb DNA pol III, indicating that the formation of the DNA Pol III holoenzyme does not influence the role of β2 in regulating the polymerase and exonuclease activity of α and ‘ε’ (Fig. 6e).

Discussion

The Mtb DNA polymerase III system, responsible for the accurate and rapid replication of its chromosomal DNA and thus a significant and promising drug target, is poorly understood. Here, we have successfully reconstituted leading-strand replication of the Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme in vitro, and systematically characterized the physical and functional relationships between α, ‘ε’ and β2, its key components. We demonstrate that ‘ε’, like its E. coli counterpart30, is an exonuclease (Fig. 2a) and confirm recent findings that α has 3′–5′ ssDNA exonuclease activity in addition to its 5′–3′ DNA polymerase activity21 (Fig. 3a). We show that α becomes a highly efficient DNA polymerase only when associated with ‘ε’, the sliding clamp and clamp loader to form the holoenzyme (Fig. 1c). The β2 clamp of Mtb DNA pol III interacts tightly with both α and ‘ε’ (Fig. 4), and its presence appears to play an important regulatory role in the function of the αβ2‘ε’ replicase, increasing its polymerase and reducing its exonuclease activity. Our findings provide novel insights into the mechanism by which these two activities are balanced in Mtb DNA pol III, and open up new avenues of research on the proliferation and emergence of drug-resistance in this pathogen.

Our study provides direct experimental evidence that a bacterial DNA pol III can have two potential proofreading subunits. The ssDNA exonuclease activity of Rv3711 (‘ε’) (Fig. 2a), its strong physical interaction with the β2 clamp (Fig. 4b), the fact that ‘ε’ considerably enhances the polymerase activity of the α subunit (Fig. 5c), and that its own exonuclease activity is reduced by β2 in the presence of α (Fig. 6a) lead us to conclude that Rv3711 (‘ε’) is the Mtb homologue of the E. coli ε subunit and an integral part of a core αβ2ε replicase in Mtb. The presence of exonuclease activity in both α and ‘ε’ in Mtb DNA pol III (Figs. 2 and 3), then, is different from the sole ε proofreading subunit of E. coli and the sole αPHP proofreading subunit in T. thermophilus31. The presence of an exonuclease active site in the αPHP domain, as in the T. thermophilus α subunit, has previously been thought to preclude the involvement of the ε exonuclease in DNA pol III33. Here, we verified that the Mtb DNA pol III α subunit, like the T. thermophilus α subunit19, and in agreement with the findings of Rock et al.21, has an intact PHP active site which also has 3′–5′ ssDNA exonuclease activity (Fig. 3a). Our findings show that exonuclease activity in Mtb DNA pol III ‘ε’ and α is not mutually exclusive and both probably serve as proofreading subunits in genomic replication. While the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ here was much stronger than that of α in in vitro assays (Figs. 2c and 3c), Rock et al’s recent work published during the preparation of this paper suggests that α may actually execute the main proofreading activity in living cells and may be an ancestral prokaryotic proofreader21.

In contrast to E. coli where α, ε and β2 all physically interact with each other in vitro, we found that Mtb α does not directly associate with ‘ε’ (Supplementary Figure S3), the β2 clamp playing an important bridging role in the αβ2‘ε’ replicase connecting α and ‘ε’ (Fig. 4). In E. coli, the α-ε interaction is strong enough to support a stable αε complex17, and plays an important role in the formation of the αεθ:β2 replicase34. Here, co-immunoprecipitation assays demonstrated that α, ‘ε’ and β2 form an αβ2‘ε’ replicase in vivo (Fig. 4a), similar to the αεθ:β2 replicase of E. coli. α-β2 and ‘ε’-β2 interactions are much stronger in Mtb than those in E. coli22,36 and may be essential for the formation of the Mtb αβ2‘ε’ replicase (Fig. 4b,c). The organization of the Mtb αβ2‘ε’ replicase reported here provides a physical foundation for elucidating the dynamic assembly of the Mtb DNA pol III subunits during the functional switches between replication and proofreading.

As in E. coli, functional interactions in the αβ2‘ε’ replicase of Mtb DNA pol III are important; ‘ε’ and β2 are necessary for α to maintain its native replication rate (Fig. 5c,d). In E. coli DNA pol III, the association of α and ε increases α polymerase activity by about 3-fold, and the ε exonuclease by 10- to 80-fold37, and the association of the β2 clamp with α also increases its polymerase activity40. Here, as in E. coli, both β2 and ‘ε’ are able to increase the polymerase activity of α, with β2 promoting the polymerase activity much more strongly than ‘ε’ (Fig. 5c,d). We also found that β2 is unable to reduce ‘ε’ exonuclease directly (Fig. 6d). Although we were unable to determine if α enhances the exonuclease activity of ‘ε’ in Mtb as it does in E. coli, we have shown that α does at least not reduce its activity (Fig. 5a).

Our results suggest that Mtb DNA pol III may be a good model for studying the mechanism by which DNA pol III switches from proofreading to polymerization mode; an equimolar mixture of Mtb DNA pol III α and ‘ε’ natively exhibits strong exonuclease activity on paired dsDNA (Fig. 5a, Lane 6), whereas the αε complex of E. coli DNA pol III mainly exhibits polymerase activity and has extremely weak exonuclease activity on paired dsDNA37. In E. coli, DNA pol III regulates these two activities by switching between polymerization and proofreading modes22,23. Jergic et al. have proposed that interactions between the α, ε and β2 subunits, especially an intact ε-β2 interaction, are essential for stabilizing the replicase in polymerization mode, and that disruption of the ε-β2 interaction in the E. coli αεθ:β2 replicase is necessary for the switch from polymerization mode to proofreading mode when sufficient amounts of the four dNTPs are present in the reaction22. However, Toste Rêgo et al. have reported that an intact ε-β interaction is also required for DNA pol III to maintain optimal proofreading activity when the polymerase runs out of dNTPs, and suggest that an intact ε-β2 interaction may play an important role in stabilizing the replicase in proofreading mode by positioning the ε exonuclease closer to the DNA substrate23. Our results suggest that the presence of the β2 clamp may play an important regulatory role in balancing the polymerase and exonuclease activities of DNA pol III in Mtb; the presence of the β2 clamp in the Mtb αβ2‘ε’ replicase promoted polymerase activity and reduced exonuclease activity (Fig. 6a), suggesting that β2 facilitates the switch in Mtb DNA pol III from proofreading to polymerization mode. This promotion of polymerase activity is likely due to a direct enhancing effect of the β2 clamp on the α polymerase in the absence of ‘ε’ (Fig. 5d). The β2 clamp’s reduction of exonuclease activity likely requires ongoing DNA polymerization as it does not reduce ε exonuclease activity in the absence of α or the four dNTPs (Fig. 6c,d). This observed regulatory role of β2 on the polymerase and exonuclease activities of Mtb DNA pol III, especially its reduction of exonuclease activity, may be important for Mtb DNA pol III to replicate the genome rapidly (Figs 5a and 6a).

In addition, we found that whether conditions are suitable or not for ongoing polymerization (the presence of enough dNTPs) may also affect the regulation of the polymerase and exonuclease activities of Mtb DNA pol III. We found that when conditions were suitable for DNA polymerization (when the four dNTPs were added), the presence of β2 contributed to the transition of DNA pol III from proofreading to polymerization mode (Fig. 6a), in agreement with the observations of Jergic et al. in E. coli22. However, when conditions were unsuitable (the four dNTPs were absent), the exonuclease activity of Mtb DNA pol III was not reduced by the presence of β2 (Fig. 6c), an observation which does not contradict Toste Rêgo et al.23. The ‘ε’-β interaction may also play an important role in this process as suggested by Toste Rêgo et al.23, but further study is required to confirm this. We conclude that, in addition to the interactions between subunits, conditions suitable for ongoing polymerization may be required for Mtb DNA pol III to switch from proofreading to polymerase mode, and speculate that the differences observed by Jergic et al. and Toste Rêgo et al. in the effects of the ε-β interaction on regulating the polymerase and exonuclease activities of E. coli DNA pol III22,23 may have been due to whether conditions in their experiments, i.e., the presence or absence of dNTPs, were suitable or not for ongoing polymerization. Moreover, while blockage of ongoing polymerization has been considered a common signal that triggers the transition from polymerization to proofreading22, translesion DNA synthesis41, or recycling the polymerase to the next Okazaki fragment42, we speculate that conditions suitable for ongoing polymerization may correspondingly serve as a prerequisite for inducing the transition from other functional states back to the polymerization mode. Further investigation is required to substantiate this hypothesis.

Our reconstitution of the Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme and leading-strand replication in vitro (Fig. 1c) provides a foundation that may contribute to the development of TB drugs targeting bacterial replication. The structure of the active center of bacterial DNA pol III43,44 is very different from that of eukaryotic genome replicases45, making the DNA pol III system a promising target for the development of patient-friendly drugs. A number of DNA pol III holoenzyme systems from other bacteria have been reconstituted46,47,48 and used to screen antibacterial agents49,50. As DNA pol III is a complex macromolecular machine in which multiple subunits interact synergistically at different stages of replication4, screening of DNA pol III inhibitors should be based on the replication process of the complete replicase in order to identify inhibitors that not only target the active sites of individual subunits, such as the 6-anilinouracil inhibitors of the Gram-positive Pol C replicase51, but also those, such as bacteriophage peptides, that block intermolecular interactions at specific stages52. Our reconstitution of leading-strand replication by the Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme provides an experimental platform that will facilitate studies on the Mtb DNA pol III replication mechanism and screening for effective drugs at the level of the complete replicase.

In conclusion, our reconstitution of Mtb DNA pol III holoenzyme leading strand replication and investigation of the physical and functional relationships between its key components, α, β2 and ‘ε’, has not only laid a foundation for studies on the Mtb DNA replication mechanism and the screening of drugs against bacterial replication, but has also provided important insights on the mechanism by which DNA pol III regulates its polymerase and exonuclease activities. It will indeed be of interest to see whether the characteristics of Mtb DNA pol III identified here, including the potential involvement of two proofreading subunits and a potential regulatory role played by the β2 clamp, do indeed affect the replicative rate and fidelity of the Mtb genome and influence proliferation and emergence of drug-resistance in this pathogen.

Methods

Protein purification

The Mtb DNA Pol III α and ‘ε’ subunits, clamp loading complex and single-strand binding protein (SSB) were cloned, expressed and purified in E. coli. A detailed description of procedures used is provided in the Supplementary Methods. Expression of the β2 clamp in E. coli was induced with 0.4 mM IPTG. It was purified as described previously11.

DNA

Oligonucleotides used in biochemical assays were synthesized by BGI, Shenzhen, China, and their sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Radioactive oligonucleotides were labeled with [γ-32P] ATP (6000 Ci/mmol) (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4 PNK) (New England Biolabs). The SSB-coated primed-M13mp18 ssDNA template used in the leading-strand replication assay was prepared by annealing a 5′-32P-labeled 30-mer (map positon 6852–6881) to M13mp18 ssDNA (New England Biolabs) in a 1:1 molar ratio in annealing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl) at 94 °C for 4 min and then slowly cooling it to room temperature over 8 h. The annealed DNA mixture was then incubated with a 350-fold molar excess of SSB4 at 16 °C for 2 h. In exonuclease activity assays, 5′-32P-labeled 40-mers or 5′-32P-labeled 20-mers were adopted as single-strand DNA substrates, and 5′-32P-labeled 40-mers were annealed to the unlabeled single-stranded oligonucleotides Template-40 (40-mers) and Template-50 (50-mers) in a 1:1.2 molar ratio to produce radioactive blunt-dsDNA and 5′ overhanging-dsDNA substrates, respectively. In primer-extension assays, a 5′-32P-labeled 20-mer was annealed to unlabeled ssDNA Template-40 to serve as the substrate.

DNA Pol III holoenzyme leading-strand replication assay

The holoenzyme of the Mtb DNA Pol III was reconstituted using proteins purified from E. coli (Supplementary Methods). The α, β2 and ‘ε’ subunits were mixed at a molecular ratio of 1:1:1 and pre-incubated at 16 °C for 2 h to fully interact with each other and the clamp loader complex (τ3δδ’) was purified by co-lysing cells expressing the τ, δ, and δ’ subunits. An isotope-labelled primed single-stranded phage genomic DNA (M13mp18) was used as the substrate to mimic the leading-strand in genomic replication. Standard leading-strand replication reactions contained 2.5 nM SSB-coated primed-M13mp18 ssDNA template, 1 μM αβ2‘ε’, 0.5 μM clamp loader (τ3δδ’), 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 2 mM ATP, and 10 mM MgCl2 in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, containing 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 50 μg/ml BSA, in a final volume of 80 μl. The reaction was started by the addition of the αβ2‘ε’ mixture and 10 μl aliquots were removed at each time point indicated and quenched by adding 6.6 μl loading buffer (62.5% deionized formamide, 1.14 M formaldehyde, 200 μg/ml bromphenol blue, 200 μg/ml xylene cyanole, 50 mM MOPS, 12.5 mM sodium acetate, and 100 mM EDTA pH 8.0). A control leading-strand replication reaction with the α subunit alone was performed in an identical manner, except that the DNA Pol III holoenzyme was replaced by the α subunit. One-half of the quenched reaction in each case was heated to 94 °C for 3 min and then chilled on ice immediately before loading on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea.

Exonuclease activity assays

Standard exonuclease reactions contained 5 nM radioactive DNA substrate, ‘ε’ or α subunits at the indicated concentrations and 10 mM MgCl2 in 20 μl of reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 50 μg/ml BSA). MgCl2 was replaced by other divalent metal ions where indicated. Reactions were initiated upon the addition of the enzyme (‘ε’, ‘ε’-exo or α) and quenched with 13.2 μl loading buffer after incubating at 37 °C for 30 min. A quarter of each quenched reaction was analyzed by 15% denaturing (8 M urea) PAGE.

ICP-OES quantitation of metal ions

Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was performed on a Vista MPX (VARIAN) at Tsinghua University, Beijing, China. All chemicals used were ultra-pure reagents from Sigma, St Louis, USA. Samples consisted of 3 ml of 1 mg/ml purified Mtb ‘ε’ subunit solution in analysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol). Quantities of Mg2+ and Mn2+ bound to native ε were measured by analyzing the specific atomic emission spectra of different metal ions in continuous spectra of the samples.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays

Antibodies against the α, β and ‘ε’ subunits were prepared at the Institute of Genetics and Development Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, by immunizing mice with the corresponding protein. Lysate-supernatants from exponentially growing Mtb H37Rv cultures were prepared as described in the Supplementary Methods. Supernatants were incubated with sufficient Protein G Agarose beads (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 4 °C for 8 h, and then centrifuged at 700 g for 3 min to remove proteins non-specifically bound to the beads. The resulting supernatants were divided into four parts and respectively incubated with anti-α, anti-β, anti-‘ε’ and pre-immune sera in the presence of protein G beads at 4 °C overnight. Pre-immune serum was used as a native control to rule out false positive results. Beads were then collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 30 μl PBS buffer. 15 μl samples were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-α or anti-β serum as primary antibodies. An HRP-conjugated EasyBlot anti-Mouse IgG (Gene Tex) which specifically bound the native form of mouse IgG and decreased the interference caused by the IgG used for Co-IP was used as a secondary antibody.

Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) assays

BLI assays were conducted with an Octet RED 96 System and AR2G sensors (Forte Bio). Sensors were soaked in 20 μg/ml β2 solution diluted by 10 mM Sodium acetate pH 4.5 (GE, Healthcare) for 10 min to coat with β2. Purified ‘ε’ was diluted to six different concentrations in BLI buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.005% (v/v) Tween20) to serve as analyte samples. After equilibrating in BLI buffer for 2 min, ‘ε’ was associated with β2 by soaking the β2-bound sensors in different concentrations of ‘ε’ for 4 min, and then disassociated by soaking in BLI buffer for 8 min. Kinetic parameters of the ‘ε’-β2 interaction were obtained by fitting sensorgrams for different concentrations of ‘ε’. The α-‘ε’ interaction was detected in the same way as the ‘ε’-β2 interaction, except that 50 μg/ml α in 10 mM Sodium acetate (pH 4.0) was immobilized on the sensors.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) assays

SPR assays were performed on a BIAcore3000 (BIAcore AB) equipped with an amino coupling CM281 chip (GE, Healthcare). Proteins used as the stationary phase in this assay were in HEPES buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol). 20 μg/ml purified β subunit in 10 mM Sodium acetate pH 4.0 (GE, Healthcare) was immobilized on the chip, generating about 1800 response units (Ru). A series of serially-diluted samples of α (0.01, 0.1 and 1 μM) in SPR buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.005% (v/v) Tween20) were injected sequentially into a channel of a β2-coated chip at 30 μl/min for 60 s, followed by SPR buffer for 300 s to determine the value of KD (α-β2).

Site-directed mutagenesis

We constructed a mutant ‘ε’-exo protein, in which residues Asp20, Glu22 and Asp104 involved in the putative active site of ‘ε’ were mutated into alanine. Mutations were introduced into the pET28a-SUMO/MtbdnaQ plasmid (see Supplementary Methods) via two PCR reactions catalyzed by Pyrobest DNA polymerase (Takara) and were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The double mutant D20A/E22A was obtained in the first PCR reaction, and the third mutation, D104A, was introduced in a second PCR reaction. Sequences of primers used in mutagenesis are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The ‘ε’-exo mutant protein was expressed and purified in the same way as the wild-type ‘ε’ subunit (Supplementary Methods).

Primer-extension assays

Primer-extension assays contained 5 nM radioactive primed dsDNA, different combinations of α, β2 and ‘ε’ at different concentrations, 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 10 mM MgCl2 in 20 μl of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 50 μg/ml BSA. Protein components were mixed and pre-incubated at 16 °C for 2 h to allow time for associations to form, and then added to initiate the reaction. After incubating for 10 min at 37 °C, reactions were quenched with loading buffer (13.2 μl). A quarter of each quenched reaction was analyzed by 15% denaturing (8 M urea) PAGE.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Gu, S. et al. The β2 clamp in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA polymerase III αβ2ε replicase promotes polymerization and reduces exonuclease activity. Sci. Rep. 6, 18418; doi: 10.1038/srep18418 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express appreciation to Dr. T. Jiang for helpful discussions on the manuscript, to Y.Y. Chen at the Protein Science Core Facility of IBP for technical help with BLI and SPR experiments, and to Dr. H.J. Zhang at the IBP radioactive isotope laboratory for guidance in the safe handling of radiolabeled chemicals. This work was supported by grants from the Key Project Specialized for Infectious Diseases of the Chinese Ministry of Health [2013ZX10003006, 2012ZX10003002]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31270121, 31170132, 31400127, U1401224], the Chinese Academy of Sciences [KJZD-EW-TZ-L04], and the Beijing Key Laboratory for Research on Drug Resistant Tuberculosis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions L.J.B., S.J.G. and H.T.Z. designed the study. S.J.G., W.J.L., S.Q.L., W.Q.Y., W.J.W., J.Y.D., J.H. and Y.Z. performed the experiments. S.J.G., H.T.Z., S.H.W., G.F.Z. J.F. and J.Z. analyzed the data. S.J.G., J.F. and H.T.Z. wrote and revised the manuscript. L.J.B. and X.-E.Z. supervised the project.

References

- Koul A., Arnoult E., Lounis N., Guillemont J. & Andries K. The challenge of new drug discovery for tuberculosis. Nature 469, 483–490, doi: 10.1038/nature09657 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014). Global Tuberculosis Report 2014 (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A. et al. Molecular memory of prior infections activates the CRISPR/Cas adaptive bacterial immunity system. Nat. Commun. 3, 945, doi: 10.1038/ncomms1937 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHenry C. S. DNA replicases from a bacterial perspective. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 403–436, doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061208-091655 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393, 537–544, doi: 10.1038/31159 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. & O’Donnell M. Cellular DNA replicases: components and dynamics at the replication fork. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 283–315, doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073859 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timinskas K., Balvociute M., Timinskas A. & Venclovas C. Comprehensive analysis of DNA polymerase III alpha subunits and their homologs in bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 1393–1413, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt900 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshoff H. I., Reed M. B., Barry C. E. 3rd & Mizrahi V. DnaE2 polymerase contributes to in vivo survival and the emergence of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell 113, 183–193 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F. et al. Essential roles for imuA’- and imuB-encoded accessory factors in DnaE2-dependent mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13093–13098, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002614107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra G., Dixit A. & L C. G. DNA polymerase III alpha subunit from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: Homology modeling and molecular docking of its inhibitor. Bioinformation. 6, 69–73 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui W. J. et al. Crystal structure of DNA polymerase III beta sliding clamp from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 405, 272–277, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.027 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukshal V. et al. M. tuberculosis sliding beta-clamp does not interact directly with the NAD+-dependent DNA ligase. PloS One 7, e35702, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035702 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. Genome sequencing of 161 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from China identifies genes and intergenic regions associated with drug resistance. Nat. Genet. 45, 1255–1260, doi: 10.1038/ng.2735 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane D. L., Goodman M. F. & Echols H. The fidelity of base selection by the polymerase subunit of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 6465–6475 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft-Benz S. A. & Schaaper R. M. Mutational analysis of the 3′–>5′ proofreading exonuclease of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 4005–4011 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi V. & Andersen S. J. DNA repair in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. What have we learnt from the genome sequence? Mol. Microbiol. 29, 1331–1339 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K., Jergic S., Park A. Y., Dixon N. E. & Otting G. The proofreading exonuclease subunit epsilon of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III is tethered to the polymerase subunit alpha via a flexible linker. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5074–5082, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn489 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols H. & Goodman M. F. Fidelity mechanisms in DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 60, 477–511, doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002401 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stano N. M., Chen J. & McHenry C. S. A coproofreading Zn(2+)-dependent exonuclease within a bacterial replicase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 458–459, doi: 10.1038/nsmb1078 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing R. A., Bailey S. & Steitz T. A. Insights into the replisome from the structure of a ternary complex of the DNA polymerase III alpha-subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 382, 859–869, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.058 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock J. M. et al. DNA replication fidelity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is mediated by an ancestral prokaryotic proofreader. Nat. Genet. doi: 10.1038/ng.3269 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jergic S. et al. A direct proofreader-clamp interaction stabilizes the Pol III replicase in the polymerization mode. EMBO J. 32, 1322–1333, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.347 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toste Rego A., Holding A. N., Kent H. & Lamers M. H. Architecture of the Pol III-clamp-exonuclease complex reveals key roles of the exonuclease subunit in processive DNA synthesis and repair. EMBO J. 32, 1334–1343, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.68 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M. C., Nevin P., Ronayne E. A. & Beuning P. J. Selective disruption of the DNA polymerase III alpha-beta complex by the umuD gene products. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 5511–5522, doi: 10.1093/nar/gks229 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner D. F., Evans J. C. & Mizrahi V. Nucleotide Metabolism and DNA Replication. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0001-2013 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jergic S. et al. The unstructured C-terminus of the tau subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III holoenzyme is the site of interaction with the alpha subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 2813–2824, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm079 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasiya K. R. et al. Polymerase manager protein UmuD directly regulates Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III alpha binding to ssDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 8959–8968, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt648 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeruzalmi D., O’Donnell M. & Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the processivity clamp loader gamma (gamma) complex of E. coli DNA polymerase III. Cell 106, 429–441 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan S. et al. Hydrolysis of the 5′-p-nitrophenyl ester of TMP by the proofreading exonuclease (epsilon) subunit of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III. Biochem. 41, 5266–5275 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros G. A. et al. Reaction mechanism of the epsilon subunit of E. coli DNA polymerase III: insights into active site metal coordination and catalytically significant residues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1550–1556, doi: 10.1021/ja8082818 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane S., Nakagawa N., Kuramitsu S. & Masui R. Characterization of DNA polymerase X from Thermus thermophilus HB8 reveals the POLXc and PHP domains are both required for 3′-5′ exonuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2037–2052, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp064 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banos B., Lazaro J. M., Villar L., Salas M. & de Vega M. Editing of misaligned 3′-termini by an intrinsic 3′-5′ exonuclease activity residing in the PHP domain of a family X DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5736–5749, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn526 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros T. et al. A structural role for the PHP domain in E. coli DNA polymerase III. BMC Struct. Biol. 13, 8, doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-13-8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K. et al. Proofreading exonuclease on a tether: the complex between the E. coli DNA polymerase III subunits alpha, epsilon, theta and beta reveals a highly flexible arrangement of the proofreading domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 5354–5367, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt162 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. R. & McHenry C. S. Identification of the beta-binding domain of the alpha subunit of Escherichia coli polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20699–20704 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrmann P. R. & McHenry C. S. A bipartite polymerase-processivity factor interaction: only the internal beta binding site of the alpha subunit is required for processive replication by the DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Mol. Biol. 350, 228–239, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.065 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki H. & Kornberg A. Proofreading by DNA polymerase III of Escherichia coli depends on cooperative interaction of the polymerase and exonuclease subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 4389–4392 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. R. & McHenry C. S. In vivo assembly of overproduced DNA polymerase III. Overproduction, purification, and characterization of the alpha, alpha-epsilon, and alpha-epsilon-theta subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20681–20689 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenberg P. T., Studwell-Vaughan P. S. & O’Donnell M. Mechanism of the sliding beta-clamp of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11328–11334 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scouten Ponticelli S. K., Duzen J. M. & Sutton M. D. Contributions of the individual hydrophobic clefts of the Escherichia coli beta sliding clamp to clamp loading, DNA replication and clamp recycling. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2796–2809, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp128 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. D. & Walker G. C. Managing DNA polymerases: coordinating DNA replication, DNA repair, and DNA recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 8342–8349, doi: 10.1073/pnas.111036998 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu R. E., Kurth I. & O’Donnell M. E. Single-molecule studies reveal the function of a third polymerase in the replisome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 113–116, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2179 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey S., Wing R. A. & Steitz T. A. The structure of T. aquaticus DNA polymerase III is distinct from eukaryotic replicative DNA polymerases. Cell 126, 893–904, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.027 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers M. H., Georgescu R. E., Lee S. G., O’Donnell M. & Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the catalytic alpha subunit of E. coli replicative DNA polymerase III. Cell 126, 881–892, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.028 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan M. K., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash S. & Aggarwal A. K. Structural basis of high-fidelity DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase delta. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 979–986, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1663 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck I. & O’Donnell M. The DNA replication machine of a gram-positive organism. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 28971–28983, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003565200 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders G. M., Dallmann H. G. & McHenry C. S. Reconstitution of the B. subtilis replisome with 13 proteins including two distinct replicases. Mol. Cell 37, 273–281, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.025 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner N. A. et al. Real-time single-molecule observation of rolling-circle DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, e27, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp006 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Dicker I. B., Kurilla M. G. & Pompliano D. L. PolC-type polymerase III of Streptococcus pyogenes and its use in screening for chemical inhibitors. Anal. Biochem. 304, 110–116, doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5591 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallmann H. G. et al. Parallel multiplicative target screening against divergent bacterial replicases: identification of specific inhibitors with broad spectrum potential. Biochem. 49, 2551–2562, doi: 10.1021/bi9020764 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly J. S. et al. In vitro antimicrobial activities of novel anilinouracils which selectively inhibit DNA polymerase III of gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 2217–2221 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. Antimicrobial drug discovery through bacteriophage genomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 185–191, doi: 10.1038/nbt932 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.